Abstract

Background/aims

The receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic microvascular complications. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between 2245G/A gene polymorphism of the RAGE gene and retinopathy in Malaysian type 2 diabetic patients.

Methods

342 unrelated type 2 diabetic patients (171 with retinopathy (DR), 171 without retinopathy (DNR)) and 235 unrelated healthy subjects from all over Malaysia were recruited for this study. Genomic DNA was isolated from 3 ml samples of whole blood using a modified conventional DNA extraction method. The genotype and allele frequencies of 2245G/A were studied using the polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method.

Results

A statistically significant difference in 2245A minor allele frequency was found between control (5.5%) and DR groups (15.2%) (p<0.001, OR=3.06, 95% CI 1.87 to 5.02) as well as between DNR (8.2%) and DR (15.2%) groups (p<0.01, OR=2.01, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.27). However, when the frequency was compared between control and DNR groups, there was no significant difference (p>0.05).

Conclusions

This is the first study that shows an association between the 2245A allele of the RAGE gene and development of diabetic retinopathy in the Malaysian population.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, Malaysian, polymorphism, rage gene, genetics

Introduction

Retinopathy is the second leading cause of vision loss due to the degeneration of the retina and affects the quality of life of type 2 diabetic patients.1 A number of studies have attempted to identify genes and their variants that are associated with retinopathy across different populations, and this includes the gene encoding the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE). RAGE is a multi-ligand member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell surface molecules, and RAGE gene is located on chromosome 6p21.3 at the major histocompatibility complex locus in the class III region and composed of 11 exons as well as a 3′ UTR.2 RAGE has been shown by in vivo and in vitro studies to play a role in the pathogenesis of diabetic microvascular complications.3

RAGE recognises a wide range of endogenous ligands including advanced glycation end-products (AGE) and its expression is upregulated in patients with retinopathy.4 AGE are complex, heterogenous molecules formed from non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation of protein, lipids and nucleic acids.5 6 A serious consequence of AGE formation is their sustained interaction with RAGE, which leads to a positive feedback loop that enhances the expression of RAGE in the retina. This activates the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which causes deleterious effects.5–8 Genetic polymorphism in RAGE could alter this sequence of events by changing the expression of RAGE and thereby affect the course of the disease.

Most of the RAGE polymorphisms that have been identified comprise either rare coding changes or are located in non-coding regions.9 10 2245G/A RAGE polymorphism, situated at intron 8 region, is of interest due to its relatively high prevalence, and the nucleotide change can be rapidly screened using the polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method. Only a few studies have investigated the relationship between this polymorphism and diabetic retinopathy (DR) and these were carried out in limited populations. However, no positive association data have been reported.11 In this study, we aimed to investigate the association of 2245G/A RAGE gene polymorphisms with retinopathy in the Malaysian type 2 diabetic population.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

The study sample was recruited from a pool of diabetic patients referred by the Diabetic Clinic for eye examination at the Ophthalmology Clinic in the University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Malaysia. Patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes with less than 1 year duration of retinopathy were excluded from the study. A total of 342 unrelated consecutive type 2 diabetic patients (with and without retinopathy) (198 men, 144 women) aged 57.9±9.8 years (mean±SD; range 35 to 79 years) were recruited for this study. Detailed medical and ophthalmologic histories as well as socio-demographic factors and lifestyle variables were noted. All previous ophthalmologic procedures, including panretinal laser photocoagulation and/or pars plana vitrectomy, were recorded.

Six ml of blood was obtained from each subject for the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) study. Three ml of the blood was sent for routine blood examination in Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory at the University Malaya Medical Centre. All the patients underwent a complete eye examination that included dilated retinal examination and seven-field stereoscopic Diabetic Retinopathy Study retinal photography.12 The colour fundus photographs were graded for DR severity in a masked fashion by two independent ophthalmologists at University of Malaya Eye Research Center in Kuala Lumpur. The modified Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study Airlie House classification of DR was used to grade the retinopathy into the following categories: mild non-proliferative retinopathy (mild NPDR), moderate non-proliferative retinopathy (moderate NPDR), severe non-proliferative retinopathy (severe NPDR) and proliferative retinopathy (PDR).13 14

Among the 342 recruited diabetic patients, 171 patients were without retinopathy (DNR) and 171 with retinopathy (DR). Among the DR patients, there were 27 mild NPDR patients, 72 moderate NPDR patients, nine severe NPDR patients and 63 PDR patients. The non-retinopathy controls were recruited from volunteer blood donors. They consisted of 235 unrelated healthy subjects (134 men, 101 women) aged 52.2±3.6 years (mean±SD; range 44–59 years).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA from the control subjects and the patients was isolated from 3 ml of peripheral blood by a modified conventional DNA extraction method as used in previous study.15 16 It is noteworthy that the 2245G/A polymorphism (rs55640627) was the only SNP investigated in this study. This SNP was detected using PCR-RFLP. PCR was used to amplify the intron 8 region containing this polymorphism as described previously.10 In brief, a two-step nested PCR was used since this polymorphism lies in a highly homologous region. In silico PCR as described previously was applied in this study to make sure the primers were targeted to the correct loci prior to the actual PCR.17–19 In the first PCR, the forward primer 5′ GCC CCA TTC TGG CCT TAT CCC TAA 3′ and reverse primer 5′ CCA CCA TGC CTG GCT AAT TTT GT 3′ were used to amplify a 294 bp product in a final PCR mixture of 15 μl containing 100 ng of genomic DNA and 12.5 pmol of each primer. The DNA was then subjected to initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing and elongation at 60°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 8 min. A sample of the amplified product (10 μl) was diluted with 500 μl of sterile distilled water and 1 μl was used for the second PCR. The second PCR was performed using the former reverse primer and a specific amplification-created restriction site forward primer (5′ACA CTT TGG GAG GCT GCT GC 3′) in a final volume of 20 μl to amplify a 116 bp product. The PCR amplicon was subjected to an initial denaturation (95°C for 3 min), followed by amplification comprising of 40 cycles, with each cycle consisting of a sequence of temperatures set at 94°C for 10 s, 56.7°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 8 min.

Restriction endonuclease digestion and sequencing

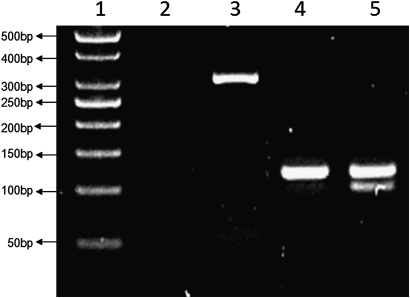

The change of nucleotide (guanine to adenine) at intron 8 region creates a PstI restriction site (CTGCA/G). Restriction analysis was performed with PCR products digested overnight with five units of restriction nuclease PstI (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) at 37°C. The digested products were immediately separated by electrophoresis in 3% (w/v) agarose gel with ethidium bromide and visualised under UV. Subsequent digestion with PstI revealed fragments of 95 bp and 21 bp for the mutated minor allele 2245A. The wild-type major allele 2245G was 116 bp long since it does not carry the restriction site (figure 1). Five representative samples from each genotype were further sequenced to confirm the overall genotyping results.

Figure 1.

Digested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products of 2245 RAGE gene intron region. Lane 1: a 50 bp DNA ladder; lane 2: DNA blank; lanes 3–5: first-step PCR product (294 bp), wild-type homozygote for 2245GG (116 bp) and heterozygote for 2245GA (116 bp and 95 bp).

Statistical analysis

The unpaired t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test were used for the evaluation of differences in biochemical variables among the groups. For the evaluation of gene polymorphism, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and dichotomous variables were examined in the studied groups using χ2 test with one degree of freedom.20 The statistical significance of differences in allele frequencies among the three groups was tested by two-tailed Fisher's exact test. For each OR, 95% CI was calculated. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. GraphPad Prism for Windows V.5.02 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, San Diego, California, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The demographic data for the healthy controls, and the DNR and DR patients, are shown in table 1. Both DNR and DR patients had significantly (p<0.05) higher levels of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein, and higher systolic blood pressure and frequency of hypertension than healthy controls. Comparison between the DNR and DR groups showed that patients in the DR group were younger, had higher levels of HbA1c and total cholesterol, had longer diabetes duration and were less likely to be smokers (all p<0.05). No significant differences (p>0.05) were observed in body mass index, levels of triglyceride, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, diastolic blood pressure, the number of subjects with alcohol intake, and the number of subjects with hypertension.

Table 1.

Demographic data for healthy controls, and DNR and DR groups

| Demography | Healthy controls (n=235) | DNR (n=171) | DR (n=171) |

| Sex (male/female) | 198/144 | 100/71 | 98/73 |

| Age (years) | 55.2±5.0 | 59.2±9.6† | 56.1±10.1‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6±4.8 (n=183) | 27.2±4.4 | 26.4±5.3 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6±0.4 (n=183) | 7.9±1.8† | 9.0±2.1†‡ |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.8±0.6 (n=183) | 4.5±1.0† | 4.9±1.6†‡ |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 1.8±1.3 (n=183) | 1.6±0.7 | 1.7±0.9 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 1.0±0.3 (n=183) | 1.2±0.3† | 1.3±0.3† |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 2.1±0.5 (n=183) | 2.5±0.9† | 2.8±1.3† |

| ALT (IU/l) | 30–65* | 37.8±17.5 | 36.0±18.6 |

| AST (IU/l) | 15–37* | 22.0±14.0 | 21.0±14.3 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 124.0±8.0 (n=183) | 136.5±19.5† | 141.0±22.5† |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 83.0±7.0 (n=183) | 79.0±10.5† | 80.1±12.6 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | – | 10.4±7.9 | 14.8±8.6‡ |

| Current smoker (yes/no) | 43/192 | 29/142 | 14/157†‡ |

| Alcohol intake (yes/no) | 70/165 | 24/147† | 18/153† |

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 11/224 | 134/37† | 137/34† |

Data are expressed as mean±SD.

Dichotomous variables are given in absolute numbers and tested with χ2 test.

Normal value range provided

p<0.05 versus healthy controls

p<0.05 versus DNR.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DNR, diabetic non-retinopathy; DR, diabetic retinopathy; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Genotype distribution and allele frequency of 2245G/A polymorphism in the healthy controls, and DNR and DR groups are shown in table 2. The distribution of the genotype did not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in any of the groups except for the DR group. The gene and allele frequencies for 2245G/A polymorphism were GG 88.9%, GA 11.1%, AA 0% (G 94.5%, A 5.5%) for the healthy control group, GG 83.6%, GA 16.4%, AA 0% (G 91.8%, A 8.2%) for the DNR group, and GG 69.6%, GA 30.4%, AA 0% (G 84.8%, A 15.2%) for the DR group. Our study did not detect 2245AA minor genotype in any of the groups. A statistically significant difference in 2245A minor allele frequency was found between the control (5.5%) and DR (15.2%) groups (p<0.001, OR=3.06, 95% CI 1.87 to 5.02) as well as between the DNR (8.2%) and DR (15.2%) groups (p<0.01, OR=2.01, 95% CI 1.24 to 3.27). However, when control and DNR groups were compared, there was no significant difference (p>0.05).

Table 2.

Genotype distribution and allele frequency of 2245G/A polymorphisms in the groups studied

| Clinical group | Genotype distribution | Allele frequency (%) | p Value | HWE | |||

| GG | GA | AA | G | A | |||

| Control (n=235) | 209 (88.9) | 26 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 94.5 | 5.5 | – | 0.81 |

| DNR (n=171) | 143 (83.6) | 28 (16.4) | 0 (0.0) | 91.8 | 8.2 | NS | 1.36 |

| DR (n=171) | 119 (68.6) | 52 (31.4) | 0 (0.0) | 84.8 | 15.2 | <0.001 (<0.01*) | 5.5 |

Data are reported as values with per cent in parentheses unless otherwise indicated.

Compared with DNR.

DNR, diabetic non-retinopathy; DR, diabetic retinopathy; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in χ2 value.

Discussion

Muller cells regulate some important features of early retinal vascular damage in DR, such as vascular permeability and homeostasis.21 The role of RAGE in the pathogenesis of diabetic-related eye complication was supported by a recent finding of predominant expression of RAGE in the retinal glia (Muller cells) of diabetic rats compared with non-diabetic rats.21 The accumulation of AGE in an individual could increase the retinal endothelial cell permeability causing vascular leakage. Certain cytokines, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, could be induced through the AGE–RAGE interaction, leading to neovascularisation and angiogenesis that could result in retinopathy.22 Soluble RAGE (sRAGE) is a naturally occurring inhibitor of signalling pathways induced by RAGE as it can remove AGE by acting as a decoy and blocking the AGE–RAGE interaction.23 A critical event in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy is the inappropriate adherence of leucocytes to the retinal capillaries.7 In 2003, Moore et al showed that sRAGE was able to reduce AGE-induced leucocyte adhesion to endothelial cell monolayers.7

Although the functional effect of the intronic polymorphism is unknown, the possibility of its quantitative impact on RAGE expression should not be ruled out. sRAGE is produced by alternative splicing of RAGE mRNA, which involves regions between intron 7 and 9.24 The intron 8 region in which the 2245G/A polymorphism is present could hypothetically be involved in this regulatory process. The level of sRAGE has been shown to be significantly reduced in diabetic retinopathy patients compared with healthy controls.23–25 Kankova et al performed a pilot study in 2002 by investigating the relationship of three RAGE intron polymorphisms with diabetic retinopathy in Caucasians.11 They reported that intron polymorphism 2245G/A was probably not involved in the genetic modification of susceptibility to the development of proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

In this study, we found that 2245A minor allele was significantly present (p<0.001) in the DR group (15.2%) compared with the DNR group (8.2%) (table 2). We hypothesise that individuals with increased 2245A allele frequency could have greater AGE–RAGE interaction due to low sRAGE level and a higher risk of developing retinopathy. This genetic predisposition is probably independent of diabetes itself. However, the actual mechanism of how it affects the disease development still needs to be shown in functional studies. It is possible that the effect of 2245A allele may be related to linkage disequilibrium with a nearby causative factor that was not investigated in this study. The negative finding by Kankova et al11 could be due to small sample size of Caucasian DR patients (n=75); the study lacked power and this could have led to a false-negative result. Differences in genetic background and population history may also contribute to this contradictory finding. Recently, Balasubbu et al reported that another RAGE gene polymorphism, Gly82Ser, was associated with DR in south Indians.26 However, this polymorphism is not likely to be in linkage disequilibrium with the 2245G/A polymorphism since it was reported as a low risk allele for DR in south Indians26 and the population histories of south Indians and Malaysians are different.

In conclusion, although a recent study reported that Gly82Ser, 1704G/T and 2184A/G polymorphisms in the RAGE gene are not involved in the development of retinopathy in the Malaysian population,27 this is the first study showing that 2245A allele of RAGE gene is associated with the development of retinopathy in Malaysian population. However, larger studies are necessary to support and substantiate this study.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by University of Malaya Research Grant, RG155-09HTM, High Impact Research Grant and University of Malaya Postgraduate Research Fund, PS239/2010A.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Malaya Medical Center (UMMC) Ethics Review Board, Malaysia. The study was performed in adherence to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Contributors: Zhi Xiang Ng, Umah Rani Kuppusamy and Kek Heng Chua carried out the experiment, data analysis and manuscript preparation. Iqbal Tajunisah, Kenneth Choong Sian Fong, Adrian Choon Aun Koay, Zhi Xiang Ng and Kek Heng Chua were involved in experimental design, sample collection, and grant and ethics applications.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Uthra S, Raman R, Mukesh BN, et al. Association of VEGF gene polymorphisms with diabetic retinopathy in a south Indian cohort. Ophthalmic Genet 2008;29:11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu WX, Feng B. The-374A allele of the RAGE gene as a potential protective factor for vascular complications in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med 2010;220:291–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt AM, Stern DM. RAGE: a new target for the prevention and treatment of the vascular and inflammatory complications of diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2000;11:368–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pachydaki SI, Tari SR, Lee SE, et al. Upregulation of RAGE and its ligands in proliferative retinal disease. Exp Eye Res 2006;82:807–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Morcos M, et al. Understanding RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Mol Med 2005;83:876–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basta G. Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts and atherosclerosis: from basic mechanisms to clinical implications. Atherosclerosis 2008;196:9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TC, Moore JE, Kaji Y, et al. The role of advanced glycation end products in retinal microvascular leukostasis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44:4457–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalousova M, Zima T, Tesar V, et al. Advanced glycoxidation end products in chronic diseases-clinical chemistry and genetic background. Mutat Res 2005;579:37–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson BI, Stickland MH, Grant PJ. Identification of polymorphisms in the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) gene: prevalence in type 2 diabetes and ethnic groups. Diabetes 1998;47:1155–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kankova K, Zahejsky J, Marova I, et al. Polymorphisms in the RAGE gene influence susceptibility to diabetes-associated microvascular dermatoses in NIDDM. J Diabetes Complications 2001;15:185–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kankova K, Beranek M, Hajek D, et al. Polymorphisms 1704G/T, 2184A/G, and 2245G/A in the rage gene are not associated with diabetic retinopathy in NIDDM: pilot study. Retina 2002;22:119–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group A modification of the Airlie House classification of diabetic retinopathy: diabetic retinopathy study report number 7. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981;21:210–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs: an extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology 1991;98(5 Suppl):786–806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group (ETDRS) Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology 1991;98:823–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chua KH, Ida H, Ng CC, et al. The identification of NOD2/CARD15 mutations/variants in Malaysian patients with Crohn's Disease. J Digest Dis 2009;10:124–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan JA, Lee PC, Wee YC, et al. High prevalence of alpha and beta-thalassemia in the Kadazandusuns in East Malaysia: challenges in providing effective health care for an indigenous group. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010. doi:10.1155/2010/706872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teh CSJ, Chua KH, Thong KL. Simultaneous differential detection of human pathogenic and non-pathogenic vibrio species using a multiplex PCR based on gyrB and pntA genes. J Appl Microbiol 2010;108:1940–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thong KL, Lai MY, Teh CSJ, et al. Simultaneous detection of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumanii, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by multiplex PCR. Trop Biomed 2011;28:21–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chua KH, Puah SM, Chew CH, et al. Interaction between a novel intronic IVS3+172 variant and N29I mutation in PRSS1 gene is associated with pancreatitis in a Malaysian Chinese family. Pancreatology 2011;11:441–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day INM. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. Amer J Epidemiol 2009;169:505–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Vom Hagen F, Pfister F, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end product expression in experimental diabetic retinopathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1126:42–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumaramanickavel G, Ramprasad VL, Sripriya S, et al. Association of Gly82Ser polymorphism in the RAGE gene with diabetic retinopathy in type II diabetic Asian Indian patients. J Diabetes Complications 2002;16:391–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Mesallamy HO, Hammad LN, El-Mamoun TA, et al. Role of advanced glycation end product receptors in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Complications 2010;25:168–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlueter C, Hauke S, Flohr AM, et al. Tissue-specific expression patterns of the RAGE receptor and its soluble forms–a result of regulated alternative splicing? Biochim Biophys Acta 2003;1630:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossin N, Wautier MP, Meas T, et al. Severity of diabetic microvascular complications is associated with a low soluble RAGE level. Diabetes Metab 2008;34:392–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balasubbu S, Sundaresan P, Rajendran A, et al. Association analysis of nine candidate gene polymorphisms in Indian patients with type 2 diabetic retinopathy. BMC Med Genet 2010;11:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng ZX, Kuppusamy UR, Rozaida Poh YM, et al. Lack of association between Gly82Ser, 1704G/T and 2184A/G of RAGE gene polymorphisms and retinopathy susceptibility in Malaysian diabetic patients. Gen Mol Res 2012. (article in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]