Abstract

Vascular remodeling plays a key role in neural regeneration in the injured brain. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are a mediator of the vascular remodeling process. Previous studies have found that progesterone treatment of traumatic brain injury (TBI) decreases cerebral edema and cellular apoptosis and inhibits inflammation, which in concert promote neuroprotective effects in young adult rats. However, whether progesterone treatment regulates circulating EPC level and fosters vascular remodeling after TBI have not been investigated. In this study, we hypothesize that progesterone treatment following TBI increases circulating EPC levels and promotes vascular remodeling in the injured brain in aged rats. Male Wistar 20-month-old rats were subjected to a moderate unilateral parietal cortical contusion injury and were treated with or without progesterone (n=54/group). Progesterone was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 16mg/kg at 1 h post-TBI and was subsequently injected subcutaneously daily for 14 days. Neurological functional tests and immnunostaining were performed. Circulating EPCs were measured by flow cytometry. Progesterone treatment significantly improved neurological outcome after TBI measured by the modified neurological severity score, Morris Water Maze and the long term potentiation in the hippocampus as well as increased the circulating EPC levels compared to TBI controls (p<0.05). Progesterone treatment also significantly increased CD34 and CD31 positive cell number and vessel density in the injured brain compared to TBI controls (p<0.05). These data indicate that progesterone treatment of TBI improves multiple neurological functional outcomes, increases the circulating EPC level, and facilitates vascular remodeling in the injured brain after TBI in aged rats.

Key words: aged rats, EPCs, neurological function, progesterone, TBI, vascular remodeling

Introduction

Neuronal cell death and cerebral vascular injury are primary pathological features of traumatic brain injury (TBI) (DeWitt et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2010). Neuronal cell death is associated with a significant suppression of angiogenesis (Xing et al., 2009), whereas neural regeneration is accompanied with vascular remodeling (Kojima et al., 2010). Vascular remodeling provides critical neurovascular substrates for neuronal remodeling after brain injury (Murasawa and Asahara, 2005; Noguchi et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2010) and is associated with long-term functional recovery after TBI (Hayward et al., 2010).

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are linked to heamogioblast stem cells and contribute to new blood vessel formation in postnatal vasculogenesis and angiogenesis (Isner and Asahara, 1999; Tepper et al., 2005). Administration of erythropoietin or statins increases mobilization of EPCs and promotes vascular remodeling, as well as improving neurological outcome after brain ischemia and hemorrhagic brain injury (Lapergue et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004; Yu and Feng, 2008). Hormonal status also modulates circulating EPCs (Bulut et al., 2007). Allogeneic infusion of EPC augments hematopoiesis and increases vascular remodeling after TBI (Kalka et al., 2000; Xue et al., 2010). EPC protects the brain against ischemic injury, promotes neurovascular repair, and improves long-term neurobehavioral outcomes after stroke in mice (Fan et al., 2010). It has not yet been investigated whether or not increased EPC levels regulate functional outcome after TBI.

Progesterone is a prototypical reproductive hormone (Carr et al., 1998). Previous studies have found that progesterone treatment induces neuroprotective effects on the injured cortical tissue (Culter et al., 2005; Labombarda et al., 2009; Shear et al., 2002) by reducing edema (Galani et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2006; Wright et al., 2001), regulating the immunological system (Culter et al., 2006; Grossman et al., 2004; He et al., 2004; Jones et al., 2005), attenuating free radical damage, and inhibiting lipid peroxidation in neural cells (Stein, 2008). Whether progesterone treatment affects circulating EPC mobilization and promotes angiogenesis or vasculogenesis after TBI have not been investigated. Furthermore, advanced age impairs new vascular formation and EPC recruitment in response to the ischemia or tissue injury, and results in a decreased capacity for tissue regeneration (Chang et al., 2007; Edelberg and Reed, 2003; Lakatta and Levy, 2003). Whether progesterone regulates EPC mobilization in aged rats after TBI has not been investigated.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the administration of progesterone starting 1 h after TBI would induce an upregulation of the circulating EPCs and promote angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in the injured brain, and thereby improve neurological functional outcome after TBI in the aged male rat. As the 15–20 month-old rats correspond to 60-year-old humans (Câmara, et al., 2010; Culter, et al., 2007), 20-month-old rats were used in this study.

Methods

TBI model

Male Wistar rats (20 months old; 500–550 g) obtained from the Experimental Animal Laboratories of the Academy of Military Medical Sciences were housed individually in a temperature-controlled (22°C) and humidity-controlled (60%) vivarium and maintained with free access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Chinese Small Animal Protection Association.

For the fluid percussion injury (FPI) model, rats were adapted to the vivarium 1 week before surgery, anesthetized with chloride hydrate (3.0 mL/kg, administered intraperitoneally), placed in a stereotaxic frame, and their scalp and temporal muscles were reflected. A 4.0-mm craniotomy was performed over the right parietal bone, 2.0 mm lateral from the sagittal suture and 3.0 mm caudal from the coronal suture. Rats were subjected to experimental FPI (model 01-B; New Sun Health Products, Cedar Bluff, VA) injury of severity of 2.0 atm, as described previously (Dixon et al., 1987; McIntosh et al., 1989). In brief, a female Leur-Lok fitting was cemented to the craniotomy site (MODEL 01-B, New Sun, USA). A syringe filled with sterile saline was inserted into the Luer-Lok syringe fitting and connected to the fluid percussion device. The pressure pulse (200–233 kPa) and pulse duration were measured by a transducer attached to the fluid percussion device. Immediately after TBI, the incision was suture closed and the rats were allowed to recover from anesthesia. Sham injured rats underwent the same surgical procedure without being exposed to percussion injury.

Administration of progesterone

Previous study has found that acute progesterone treatment at a dose of 16 mg/kg post-TBI proves an effective intervention to prevent post-injury cortical and sub-cortical edema in young and aged female rats (Kasturi and Stein, 2009) and that it promotes neuroprotective effects (Cutler et al., 2005, 2007; Goss et al., 2003; Pettus et al., 2005). Therefore, the dose of 16 mg/kg progesterone was used in this study. After injury, rats were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions: 1) TBI+progesterone (16 mg/kg) group (TBI+PR) (n=54). Progesterone was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), at <1% concentration (Zhejiang Xianju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.). 2) TBI+vehicle control: TBI+DMSO group (TBI+DMSO) (n=54). The DMSO was 1% dissolved in sterilized peanut oil. Except for the first dose, which was administered intraperitoneally to ensure more rapid absorption following injury (1 h post injury), progesterone (16 mg/kg) or DMSO (<300μl for each rat) was administered subcutaneously at 6 and 24 h post-injury and then daily for 14 days post-injury. 3) Sham injury alone (SHAM) (n=54).

To exclude DMSO toxicity on the circulating EPC levels and neurological functional outcome, we first compared the difference between SHAM alone and SHAM+DMSO rats. We found that there is no significant difference between SHAM alone and SHAM+DMSO in circulating EPC levels and neurological functional tests (data not shown). Therefore, a low dose of DMSO does not influence circulating EPC and neurological functional outcome. SHAM alone and SHAM+DMSO was combined as sham control group in this study.

Neurofunction assays

Morris Water Maze (MWM) (Zhang et al., 2009)

To test spatial learning ability, the MWM test was used. MWM is a test of spatial learning that is performed in an open swimming pool to locate a submerged escape platform. The test is performed in a 1.5 m diameter circular tank containing a round pool of water. The pool is divided into four equal quadrants (I, II, III, and IV) and a 10-cm-diameter platform is submerged beneath the water surface in the center of quadrant III. When the rat is placed in the maze, it will try to find the hidden platform. The water is made opaque using nontoxic black ink and maintained at 25±1.80C. The experimenter records the time the rat took "learning" to find the platform over a number of trials. The movement of rats in the maze is monitored by a CCD camera connected to a computer, where data are collected and analyzed. In our research, rats were subjected to two sessions of four trials per day for 5 consecutive days covering 14–18 days post-injury. In each trial, the rats were released into the water individually from one of four starting points spaced 90° apart around the perimeter of the tank. They were allowed to swim freely until they reached and stayed on the platform. If they failed to locate the platform within 120 sec, they were placed on it for 15 sec. The time required to find the platform (escape latency) and the swimming speed were recorded. Subsequent starting points proceeded in a clockwise manner for the ensuing trials. There was a 5 min interval between trials, and a 5 h interval between two sessions, respectively.

Modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) test (Chen et al., 2001)

Neurological function was evaluated by the mNSS test, which included motor, sensory, reflex, and balance tests (Chen et al., 2001). In the mNSS test, the neurological function was graded on a scale of 0 to 18 (0 referred to normal; 18 referred to maximal deficit). The test was performed at 1, 7, 14, and 21 days post- TBI by observers who were blinded to the experimental conditions and treatments. Table 1 shows a set of parameters included by mNSS. One score point was awarded for the inability to perform the test or for the lack of a tested reflex; therefore, the higher score, the more severe the injury.

Table 1.

Modified Neurological Severity Score Points

| Motor tests | |

|---|---|

| Raising rat by tail | 3 |

| Flexion of forelimb | 1 |

| Flexion of hindlimb | 1 |

| Head moved >10° to vertical axis within 30 sec | 1 |

| Placing rat on floor (normal=0; maximum=3) | 3 |

| Normal walk | 0 |

| Inability to walk straight | 1 |

| Circling toward paretic side | 2 |

| Falls down to paretic side | 3 |

| Sensory tests | 2 |

| Placing test (visual and tactile test) | 1 |

| Proprioceptive test (deep sensation, pushing paw against table edge to stimulate limb muscles) | 1 |

| Beam balance tests (normal=0; maximum=6) | 6 |

| Balances with steady posture | 0 |

| Grasps side of beam | 1 |

| Hugs beam and one limb falls down from beam | 2 |

| Hugs beam and two limbs fall down from beam, or spins on beam (>60 sec) | 3 |

| Attempts to balance on beam but falls off (>40 sec) | 4 |

| Attempts to balance on beam but falls off (>20 sec) | 5 |

| Falls off; no attempt to balance or hang on to beam (<20 sec) | 6 |

| Reflex absence and abnormal movements | 4 |

| Pinna reflex (head shake when auditory meatus is touched) | 1 |

| Corneal reflex (eye blink when cornea is lightly touched with cotton) | 1 |

| Startle reflex (motor response to a brief noise from snapping a clipboard paper) | 1 |

| Seizures, myoclonus, myodystony | 1 |

| Maximum points | 18 |

One point is awarded for inability to perform the task or for an absence of the tested reflex: 13–18, severe injury; 7–12, moderate injury; 1–6, mild injury.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) recording (Su et al. 2009)

On day 20 post-injury, each rat was anesthetized with 30% urethane (1.2 g/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic instrument (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) with its head fixed. Under a surgical microscope, the surface of the skull was exposed and two tiny holes were made in the left side with a dental drill. Incisions were made in the dura mater. Stimulating electrodes (Advent Co., Halesworth, U.K.) were placed in the Schaffer collaterals (anterior fontenelle posterior −3.1 mm, lateral to the midline 3.1 mm, dural ventral 3.0 mm). A recording electrode (Advent Co. Halesworth, U.K.) was positioned in the CA1 (AP −2.8 mm, Lat 1.8 mm, DV 2.5 mm). Both electrodes were adjusted to trigger an optimal excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) produced by the pyramidal cells of the CA1 in response to stimulation from Schaffer collaterals. Once the response stabilized, it was recorded under low-frequency stimulations (0.1 Hz) for 20 min as the baseline. Subsequently, titanic stimulation (10 pulses at 100 Hz for 5 msec repeated five times) was delivered to induce the LTP. The EPSPs were amplified by a conventional amplifier (AD Instruments Pty. Ltd., Castle Hill, Australia) at a frequency band of 5 Hz– 5 kHz, and recorded twice every minute after the tetanization. All EPSPs were monitored on an oscilloscope and digitized at a sampling interval of 20 msec for online computer display. The LTP was measured using Chart v5.3 and expressed as percentage changes of maximal initial EPSP slopes from mean response of the baseline: [(Slope after tetanus/Slope mean of baseline) x100%].

EPCs isolation and analysis

Blood samples (0.5 mL) were collected from retro-orbital venous plexus before TBI (baseline) and 3 h, 3 days, and 1, 2, and 3 weeks after TBI and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). As described previously (Liu et al., 2007), blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Isolated cells were washed twice with PBS and re-suspended in 200mL of PBS supplemented with 0.5% of bovine serum albumin and 2 mM of EDTA. Cells were labeled with the R-phycoenythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal CD133 antibody (Miltenyi Biotech, Gladbach, Germany) or/and fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated CD34 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) for 20 min at room temperature. Cells stained positive for CD34 and CD133 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA) were selected as EPCs (Friedrich et al., 2006; Lam et al., 2008; Lara-Hernandez et al., 2010).

For double fluorescence detection, cells were first gated for CD34 positive and then for CD133 staining. The double staining allowed us not only to identify EPCs, but also to determine the ratio of mature (CD34 positive cells) to immature subpopulation (CD133 positive cells). Two isotype controls of PE- and FITC-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin Gs (IgGs) were used for background nonspecific binding.

Immunofluorescence staining

Rats were killed before TBI and 7 days after TBI for brain tissue immnunostaining. Rats were anesthetized with 10% chloride hydrate. A transcardial perfusion first with saline and then with 4% paraformaldehyde was performed. The brains were removed from the skull, embedded with in OCT medium (Leica 0201 06926, Germany) and stored at −80°C. For immunohistochemical staining, coronal sections (5 μm) were obtained from the frozen brain tissue through the TBI zone or its ipsilateral hippocampus zone.

In order to examine the neo-angiogenesis related to the mobilization of EPCs, brain sections cut at an interval of 10 μm from injured cortical tissue and ipsilateral hippocampus were mounted on slides and dried. After treating with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min, the slides were rinsed in 10 μM PBS 3 times, for a total of 15 min, and blocked with the normal bovine serum at 37°C for 30 min. Slides were then incubated with 100–400 μl diluted either with a goat anti-rat primary antibody of CD31, CD34 (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), or von Willebrand factor (vWF, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) overnight at 4°C. The slides were washed three times with a washing buffer for 5 min each and then incubated with a TRITC-goat anti-rat IgG (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 37°C for 1 h. After washing with 10 μM PBS three times for a total of 15 min, diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used to stain the nucleus. Negative controls were similarly processed without the primary antibody. In order to count the vascular density, replacing the TRITC-goat anti-rat IgG with the anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), the vWF expression was measured in the paraffin-embedded sections as well. The number of CD31 positive, CD34 positive, and vWF positive cells in each section was counted (per 100 x, Nikon, Japan) in five fields by two independent observers who were blinded to the experimental conditions, to obtain an average number of the counted cells per view field.

Statistical analysis

SPSS16.0. ANOVA followed by a Least Significance Difference Method (LSD) was used to analyze the difference of circulating CD34 positive, CD133 positive, and CD34 positive CD133 positive cell levels, mNSS, LTP levels, and the CD34 positive, CD31 positive, and vWF positive cell counts in brain tissue. Comparisons between two groups were achieved with student's unpaired t-test. One-way ANOVA was applied to assay the different LTPs among the SHAM, TBI+PR, and TBI+DMSO rats. Bivariate correlation statistics were applied for the correlation between the circulating EPC level and the CD31 positive, CD34 positive, and vWF positive cell numbers and the vascular density, respectively. The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), and significance was accepted with p<0.05.

Results

Progesterone treatment improves the spatial learning and neurological recovery after TBI in aged rats

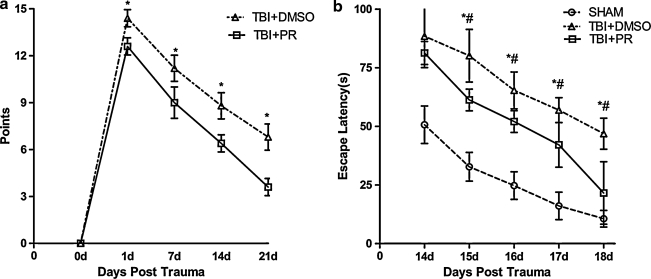

To test whether progesterone regulates functional outcome after TBI in aged rats, MWM and mNSS functional tests were performed in TBI+PR, TBI+DMSO, and SHAM groups (n=7/group), respectively. The mNSS was measured 24 h, and 1, 2, and 3 weeks post-TBI. A significant increased in the mNSS score was observed after TBI in both TBI+PR and TBI+DMSO rats. Neurological functional outcome was significantly improved in TBI+PR treated group compared to TBI+DMSO control rats from 24 h to 3 weeks after TBI (Fig. 1a).

FIG. 1.

Progesterone treatment of TBI rats significantly improved the neurological functional outcome compared with the vehicle TBI control. (a) mNSS test: The mNSS was performed in both progesterone and the DMSO-treated TBI rats from the day before injury and 1, 7, 14, and 21 days post-injury. Progesterone treatment significantly improved the neurological functional outcome of the TBI rats when compared with the control rats receiving DMSO only. There was a significant difference in the scores of the TBI+PR and TBI+DMSO rats assayed at each time point 1 day post-injury (p<0.05). (b) MWM test: The escape latency was assayed on 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 days post-injury in the SHAM, TBI+DMSO, and TBI+PR rats. The test revealed that the escape latency scored after 15 days in SHAM rats was significantly shorter than the latency in the TBI+DMSO and TBI+PR rats (p<0.05). Furthermore, the escape latency was significantly decreased in the TBI+PR group compared to the TBI+DMSO group at the same time points, except 14 days post-injury (p<0.05). n=7/group; *p<0.05 TBI+PR rats compared to TBI+DMSO rats; #p<0.05 TBI+DMSO rats compared to SHAM rats.

Spatial learning ability was measured using the MWM test. The data show that the escaping latency (EL) was significantly increased after TBI compared to sham control subjects. ELs were significantly improved by the progesterone administration in the TBI+PR rats compared to the TBI+DMSO control rats (Fig 1b). The data indicate that TBI significantly impaired neurological function and spatial learning. Administration of the progesterone significantly improved neurological outcome and spatial learning after TBI compared to TBI+DMSO control rats.

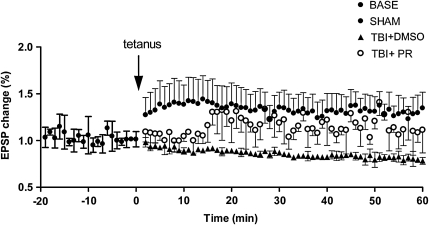

Progesterone treatment improves LTP recording after TBI

LTP is associated with long-term learning ability (Martin et al., 2000). LTP was measured in TBI+PR, TBI+DMSO, and SHAM rats (n=7/group) at 20 days after TBI, respectively. Fig. 2 shows that LTP was impaired after TBI. Progesterone treatment after TBI (TBI+PR) significantly reduced the impairment of LTP compared to TBI+DMSO controls. These data indicated that progesterone treatment induces a long-term and stable improvement in neurological function after TBI.

FIG. 2.

Progesterone treatment of TBI rats significantly improved LTP compared to the vehicle TBI control. On day 20 post-injury, Duncan's test showed that LTP was significantly decreased in TBI+DMSO rats compared to the SHAM rats (p<0.05). However, in the early term (∼10–15 min from the beginning), the LTP of the TBI+PR rats was also significantly downregulated when compared with the SHAM rats. The administration of progesterone (TBI+PR) significantly improved LTP compared to the TBI+DMSO control (p<0.05).

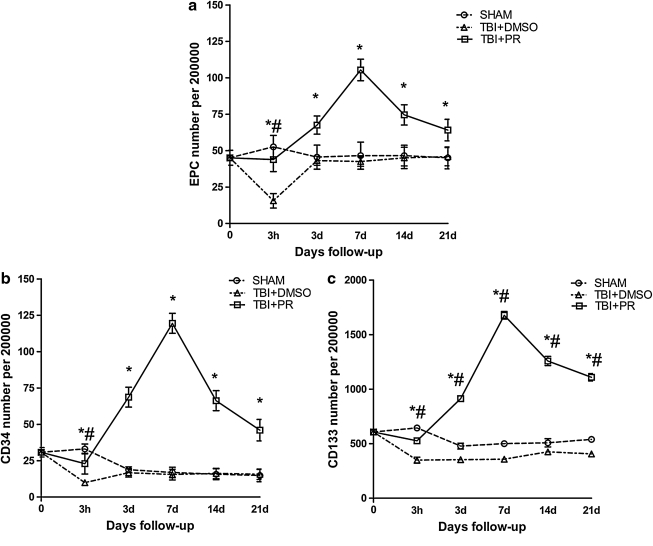

Progesterone treatment increases circulating EPC levels after TBI in aged rats

To test whether progesterone treatment regulates circulating EPC level, rats were subjected to TBI and were randomly assigned into DMSO or progesterone treatment. The sham injured rats served as controls. Blood samples were collected before TBI (baseline) and 3 h, 3 days, and 1, 2, and 3 weeks after TBI (n=5 each time point in each group, with total number of n=30/group). Fig. 3a shows that circulating EPCs were downregulated at 3 h after TBI and then returned to baseline in the TBI+DMSO group. The level of circulating EPC (defined as CD34 and CD133 positive) was significantly increased in progesterone treatment rats (TBI+PR) compared to TBI+DMSO controls as early as 3 h post-TBI, and remained at a higher level up to 21 days after TBI (Fig. 3a).

FIG. 3.

Progesterone treatment of TBI induced a significant upregulation of circulating EPCs. A significant downregulation of both the levels of EPCs (CD34 positive and CD133 positive) (a) and CD34 positive cells (b) and CD133 positive cells (c) was observed 3 h post-TBI indicating that TBI induced an early consumption of these two cell linkages in the peripheral blood. They then unregulated to a level similar to the one from the SHAM group. The administration of progesterone induced a significant quick upregulation of the EPCs, CD34 positive, and CD133 positive cells, which started from 3 h post-injury and persisted in a high level up to 21 days post-trauma, but peaked at 7 days post-injury. *p<0.05 TBI+PR rats compared to TBI+DMSO rats; #p<0.05 TBI+DMSO control compared to SHAM rats.

The CD34 represents the endothelial linage related to vascular repair (Kiernan et al., 2009). CD133 is the stem-cell marker (Ishigami et al., 2010.). We found that progesterone induced a significant increase in circulating CD34 (Fig. 3b) and CD133 (Fig. 3c) levels, which remained at a higher level throughout the course. The number of CD34 positive cells showed a parallel pattern with the change of CD133 positive cells (EPC).

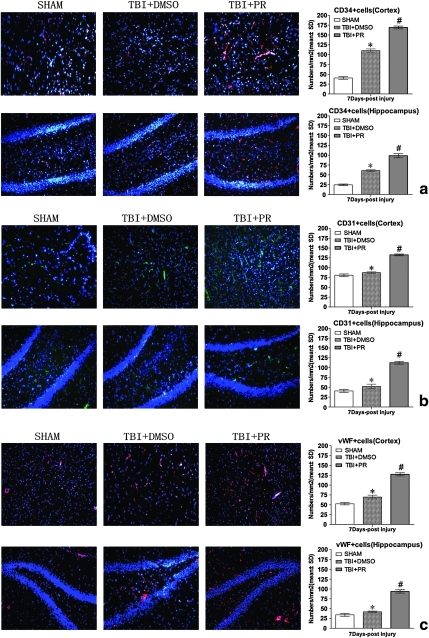

Progesterone treatment promotes angiogenesis after TBI in aged rats

CD34 is a marker of the progenitor hematopoietic cells and is also expressed in microvascular endothelial cells. The expression of CD34 in the injured tissue is an indicator of the microvascularization mediated by hematopoietic progenitors (Kiernan et al., 2009). To further test whether progesterone induces neomicrovascular formation, CD34 expression was measured in both the injured cortex and the ipsilateral hippocampus before and after TBI (n=5/time point, with total number of 10/group). Progesterone treatment (TBI+PR) significantly increased CD34 expression in the cortex and hippocampus of the ipsilateral hemisphere after TBI compared to TBI+DMSO control rats (Fig. 4a).

FIG. 4.

Progesterone treatment of TBI significantly increased CD34 positive, CD31 positive, and vWF positive cell expression in the injured brain. (a) The counting CD34 positive cells in the injured cortex and the ipsilateral dental gyrus of the TBI rats (initial magnification, × 100). (b) The counting CD31 positive cells in the injured cortical and dental gyrus after TBI (original magnification × 100). (c) The counting vWF positive cells in the injured cortical and DG after TBI (original magnification × 100). The injured cortex and ipsilateral dental gyrus in the DMSO-treated rats had more CD34 positive, CD31 positive, and vWF positive counting cells than the same regions of the sham rats (p<0.05). However, the progesterone induced more CD34 positive, CD31 positive, and vWF positive cells in the injured brain than the TBI+DMSO control (p<0.05). n=5/group. #p<0.05: TBI+PR rats compared to TBI+DMSO rats; *p<0.05: TBI+DMSO control rats compared to SHAM control rats. Color image is available online at www.liebertonline.com/neu

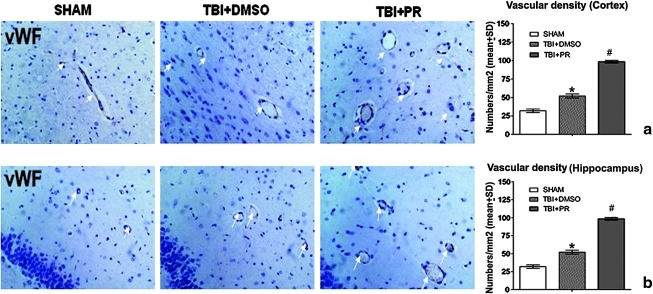

CD31 and vWF are endothelial markers (Mahooti et al., 2000). The enhanced vWF and CD31 expression indicates the induction of angiogenesis (Lu et al., 2007; Xiong et al., 2009b). We found that progesterone application significantly increased CD31 and vWF positive cells and vessel density in the injured brain tissue compared to TBI+DMSO control rats (Fig. 4b and c and Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Progesterone treatment of TBI significantly increased vascular density in the injured cortical and the ipsilateral DG at 7 days post-TBI. (a) vWF immunostaining in the injured cortex (original magnification × 400). (b) vWF immunostaining in the ipsilateral dental gyrus (original magnification × 400). Both DMSO and progesterone treating induced more vWF staining cells in both the injured cortex and the ipsilateral dental gyrus than sham control. Furthermore, progesterone application induced more vWF expression than did DMSO in TBI rats. N=5/group. #p<0.05: TBI+PR rats compared to TBI+DMSO control rats; *p<0.05: TBI+DMSO control rats compared to SHAM rats. Color image is available online at www.liebertonline.com/neu

A strong association was revealed between the numbers of CD34 positive, CD31 positive, and vWF positive cells and the circulating EPC levels, respectively (Table 2) [r=(0.756–0.928)]. The vascular density (vWF positive vessels) in the injured brain was also strongly correlated with circulating EPC levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between the Circulating EPCs Level and Other Subside Cells Levels and the Vascular Density

| Subside cells | Pearson correlation with EPCs | p |

|---|---|---|

| CD31+ cells (injured cortical tissue) | 0.928 | 0.000 |

| CD31+ cells (ipsilateral hippocampus) | 0.904 | 0.000 |

| CD34+ cells (injured cortical tissue) | 0.756 | 0.000 |

| CD34+ cells (ipsilateral hippocampus) | 0.798 | 0.000 |

| vWF+ cells (injured cortical tissue) | 0.903 | 0.000 |

| vWF+ cells (ipsilateral hippocampus) | 0.915 | 0.000 |

| Vascular density (injured cortical tissue) | 0.903 | 0.000 |

| Vascular density (ipsilateral hippocampus) | 0.889 | 0.000 |

Discussion

In this study, we found that progesterone treatment of TBI improves functional outcome after TBI, which is consistent with previous studies (Culter et al., 2005, 2007 ; Sayeed and Stein, 2009; Shear et al., 2002). In addition, we are the first to identify that progesterone treatment of TBI increases circulating EPC levels and promotes vascular remodeling in aged male rats. The increased circulating EPC level is correlated with vascular density in the injured brain tissue. Therefore, increased circulating EPC levels and vascular remodeling by progesterone treatment may contribute to improved neurological functional outcome after TBI in aged rats.

Secondary injury after TBI caused by the lack of cerebral blood supply is the primary cause of TBI morbidity and mortality (Greve and Zink, 2009; Khan et al., 2009; Zhang and Chopp, 2009). Vasculogenesis is the in situ angioblast differentiation from the EPCs to the primitive capillary network (Frontczak-Baniewicz et al., 2003; Pardanaud et al., 1989). Vasculogenesis is tightly associated with the mobilization of EPCs after TBI (Lapergue et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2009). In our previous studies, TBI induced an initial downregulation and subsequent upregulation of circulating EPCs in TBI patients (Liu et al., 2007). However, in this study, we found that the circulating EPCs were downregulated after TBI, but failed to subsequently upregulate in aged rats. A similar changing trend was also revealed in the circulating CD34 positive or CD133 positive cells. Vascular remodeling, such as angiogenesis and vasculogenesis, were impaired after brain injury and stroke in aged rats (Chang et al., 2007; Edelberg and Reed, 2003; Lakatta and Levy, 2003). These data suggested that EPC mobilization is impaired in aged rats after TBI. Decreasing EPC mobilization may contribute to vascular impairment after TBI in aged rats.

Progesterone treatment improves short-term motor recovery and attenuates edema, secondary inflammation, and cell death after TBI in aged rats (Cutler et al., 2007) and reduces secondary injury after TBI by regulating pro-coagulant factors (Vanlandingham et al., 2008). Whether or not progesterone promotes vascular remodeling after TBI in aged rats is not clear. Increased EPCs are important for neovascular regeneration and vascular reconstruction (Ladhoff et al., 2010; Maeng et al., 2009). In addition, increasing vascular remodeling improves TBI functional outcome (Jin et al., 2009; Pereira et al., 2007; Thau-Zuchman et al., 2010). In this study, we found that progesterone treatment of TBI significantly upregulates circulating EPCs, CD34, and CD133 positive cells after TBI in aged rats. EPCs or CD34 positive/CD133 positive cells have been demonstrated to repair the denuded vessel walls and to promote renewal of endothelium (Rufaihah et al., 2010; Senegaglia et al., 2010; Walter et al., 2002). CD34 positive cells play an indispensable role in angiogenesis (Al-Jarrah et al., 2010; Stellos et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010). CD34 positive cells selectively home to the sites of angiogenesis, integrate into the microvascular endothelium, and differentiate into mature endothelial cells (Krupinski et al., 2003; Morris et al., 2003). In addition, circulating CD34 positive cells secrete growth/angiogenesis factors (Guo et al., 2009; Kawamoto et al., 2006; Okada et al., 2008). CD34 positive cells isolated from the digested tissue of the saphenous vein promote angiogenesis and improve blood flow in animal models of ischemic limbs (Campagnolo et al., 2010). Consistent with the induced circulating CD34 positive cells in the peripheral blood, we found that the expression of CD34 in the injured brain tissue was significantly increased in the progesterone-treated TBI rats compared to the TBI+DMSO control rats. In addition, progesterone also significantly increased CD31 and vWF positive cells and vessel density in the injured brain. The increased CD31 and vWF expression in the injured brain are correlated with the circulating EPC levels. Therefore, progesterone treatment of TBI increases circulation and mobilization of EPC as well as promoting vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in the injured brain. The increased vasculogenesis or angiogenesis may contribute to progesterone-induced functional outcome after TBI in aged rats.

We also found that progesterone induced the upregulation of circulating EPCs (CD34 positive/CD133 positive), CD34 positive, and CD133 positive, started from 3 h, peaked at the 7th day post-TBI, and persisted to 21 days after TBI. mNSS functional outcome started at 1 day after TBI. An improvement in spatial learning ability, mNSS, and LTP were found until 20 days post-TBI. This indicates that progesterone treatment induces a long-term recovery after TBI in aged rats.

Conclusion

Progesterone has been studied in TBI for years. Progesterone promotes neuroprotective activities by reduction of cytotoxic free radicals, brain edema, and indication of antiapoptosis pathways (Atif et al., 2009; Kasturi and Stein, 2009; Shahrokhi et al., 2010). Our data add an additional important restrictive mechanism, vascular repair. Progesterone increases circulating EPCs and promotes vascular remodeling in the injured brain, which may contribute to the improvement of functional outcome after TBI. A Phase III clinical trial evaluating the effect of progesterone on TBI recovery is ongoing (Wright et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Li Liu and Fanglian Chen in our laboratory for their excellent technical support. We also acknowledge Michael Chopp from Henry Ford Hospital and Jing-fei Dong from Baylor College of Medicine for their suggestions and editing on this manuscript. This work is supported by the National 973 Projects of China (grant 2005CB522605) and Tianjin Research Program of Application Foundation and Advanced Technology (grant 11JCZDJC18100).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Al-Jarrah M. Jamous M. Al Zailaey K. Bweir S.O. Endurance exercise training promotes angiogenesis in the brain of chronic/progressive mouse model of Parkinson's disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;26:369–373. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2010-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atif F. Sayeed I. Ishrat T. Stein D.G. Progesterone with Vitamin D affords better neuroprotection against excitotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons than progesterone alone. Mol. Med. 2009;15:328–336. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blann A.D. Plasma von Willebrand factor, thrombosis, and the endothelium: the first 30 years. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;95:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton S.L. Chestnut R.M. Ghajar J. McConnell Hammond FF. Harris O.A. Hartl R. Manley G.T. Nemecek A. Newell D.W. Rosenthal G. Schouten J. Shutter L. Timmons S.D. Ullman J.S. Videtta W. Wilberger J.E. Wright D.W. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. I. Blood pressure and oxygenation. J.Neurotrauma. 2007;24(S):S7–13. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.9995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulut D. Albrecht N. Imöhl M. Günesdogan B. Bulut–Streich N. Börgel J. Hanefeld C. Krieg M. Mügge A. Hormonal status modulates circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2007;96:258–263. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Câmara C.C. Oriá R.B. Felismino T.C. da Silva A.P. da Silva M.A. Alcântara J.V. Costa S.B. Vicente A.C. Teixeira–Santos T.J. de Castro–Costa C.M. Motor behavioral abnormalities and histopathological findings of Wistar rats inoculated with HTLV-1-infected MT2 cells. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2010;43:657–662. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2010007500050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo P. Cesselli D. Al–Haj–Zen A. Beltrami A.P. Kränkel N. Katare R. Angelini G. Emanueli C. Madeddu P. Human adult vena saphena contains perivascular progenitor cells endowed with clonogenic (2010). Human adult vena saphena contains perivascular progenitor cells endowed with clonogenic and proangiogenic potential. Circulation. 2010;121:1735–1745. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.899252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr B.R. Uniqueness of oral contraceptive progestins. Contraception. 1998;58:235–275. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E.I. Loh S. A. Ceradini D.J. Chang E. I. Lin S. E. Bastidas N. Aarabi S. Chan D. A. Freedman M. L. Giaccia A. J. Gurtner G. C. Age decreases endothelial progenitor cell recruitment through decreases in hypoxia–inducible factor 1alpha stabilization during ischemia. Circulation. 2007;116:2818–2829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.715847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Li Y. Wang L. Zhang Z. Lu D. Lu M. Chopp M. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2001;32:1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S.M. Cekic M. Miller D.M. Wali B. VanLandingham J.W. Stein D.G. Progesterone improves acute recovery after traumatic brain injury in the aged rat. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1475–1486. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culter S.M. Pettus E.H. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Tapered progesterone withdrawal enhances behavioral and molecular recovery after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2005;195:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culter S.M. Vanlandingham J.W. Stein D.G. Tapered progesterone withdrawal promotes long-term recovery following brain trauma. Exp. Neurol. 2006;200:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt D.S. Prough D.S. Traumatic cerebral vascular injury: the effects of concussive brain injury on the cerebral vasculature. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:795–825. doi: 10.1089/089771503322385755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon C.E. Lyeth B.G. Povlishock J.T. Findling R.L. Hamm R.J. Marmarou A. Young H.F. Hayes R.L. A fluid percussion model of experimental brain injury in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 1987;67:110–119. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.1.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelberg J.M. Reed M.J. Aging and angiogenesis. Front. Biosci. 2003;8:s1199–s1209. doi: 10.2741/1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. Shen F. Frenzel T. Zhu W. Ye J. Liu J. Chen Y. Su H. Young W.L. Yang G.Y. Endothelial progenitor cell transplantation improves long-term stroke outcome in mice. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:488–497. doi: 10.1002/ana.21919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich E.B. Walenta K. Scharlau J. Nickenig G. Werner N. CD34-/CD133+/VEGFR-2+ endothelial progenitor cell subpopulation with potent vasoregenerative capacities. Circ. Res. 2006;98:e20–25. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205765.28940.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontczak–Baniewicz M. Walski M. New vessel formation after surgical brain injury in the rat's cerebral cortex. I. Formation of the blood vessels proximally to the surgical injury. Acta. Neurobiol. Exp. 2003;63:65–75. doi: 10.55782/ane-2003-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galani R. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Effects of the duration of progesterone treatment on the resolution of cerebral edema induced by cortical contusions in rats. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2001;18:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss C.W. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Behavioral effects and anatomic correlates after brain injury:a progesterone dose–response study. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2003;76:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve M.W. Zink B.J. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2009;76:97–104. doi: 10.1002/msj.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman K.J. Goss C.W. Stein D.G. Effects of progesterone on the inflammatory response to brain injury. Brain Res. 2004;1008:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q. Sayeed I. Baronne L.M. Hoffman S.W. Guennoun R. Stein D.G. Progesterone administration modulates AQP4 expression and edema after traumatic brain injury in male rats. Exp. Neurol. 2006;198:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. Liu L. Zhang M. Bergeron A. Cui Z. Dong J.F. Zhang J. Correlation of CD34+ cells with tissue angiogenesis after traumatic brain injury in a rat model. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1337–1344. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward N.M. Immonen R. Tuunanen P.I. Ndode–Ekane X.E. Gröhn O. Pitkänen A. Association of chronic vascular changes with functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:2203–2219. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. Evans C.O. Hoffman S.W. Oyesiku N.M. Stein D.G. Progestrone and allopregnanolone reduce inflammatory cytokines after traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2004;189:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami S. Ueno S. Arigami T. Uchikado Y. Setoyama T. Arima H. Kita Y. Kurahara H. Okumura H. Matsumoto M. Kijima Y. Natsugoe S. Prognostic impact of CD133 expression in gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:2453–2457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isner J.M. Asahara T. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesi therapeutic strategies for postnatal neovascularization. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:1231–1236. doi: 10.1172/JCI6889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X. Shen G. Gao F. Zheng X. Xu X. Shen F. Li G. Gong J. Wen L. Yang X. Bie X. Traditional Chinese drug ShuXueTong facilitates angiogenesis during wound healing following traumatic brain injury. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N.C. Constantin D. Prior M.J. Morris P.G. Marsden C.A. Murphy S. The neuroprotective effect of progesterone after traumatic brain injury in male mice is independent of both the inflammatory response and growth factor expression. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;21:1547–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalka C. Masuda H. Takahashi T. Kalka–Moll W.M. Silver M. Kearney M. Li T. Isner J.M. Asahara T. Transplantation of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:3422–3427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070046397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasturi B.S. Stein D.G. Progesterone decreases cortical and sub-cortical edema in young and aged ovariectomized rats with brain injury. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2009;27:265–275. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto A. Iwasaki H. Kusano K. Murayama T. Oyamada A. Silver M. Hulbert C. Gavin M. Hanley A. Ma H. Kearney M. Zak V. Asahara T. Losordo D.W. CD34-positive cells exhibit increased potency and safety for therapeutic neovascularization after myocardial infarction compared with total mononuclear cells. Circulation. 2006;114:2163–2169. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. Im Y.B. Shunmugavel A. Gilg A.G. Dhindsa R.K. Singh A.K. Singh I. Administration of S-nitrosoglutathione after traumatic brain injury protects the neurovascular unit and reduces secondary injury in a rat model of controlled cortical impact. J. Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan T.J. Boilson B.A. Witt T.A. Dietz A.B. Lerman A. Simari R.D. Vasoprotective effects of human CD34+ cells: towards clinical applications. J. Transl. Med. 2009;29:66–72. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T. Hirota Y. Ema M. Takahashi S. Miyoshi I. Okano H. Sawamoto K. Subventricular zone-derived neural progenitor cells migrate along a blood vessel scaffold toward the post-stroke striatum. Stem Cells. 2010;28:545–554. doi: 10.1002/stem.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupinski J. Stromer P. Slevin M. Marti E. Kumar P. Rubio F. Three-dimensional structure and survival of newly formed blood vessels after focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1171–1176. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000075304.76650.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labombarda F. Deniselle M.C. Gonzalez S.L. Garay L. Meyer M. Gargiulo G. Guennoun R. Schumacher M. Progesterone neuroprotection in traumatic CNS injury and motoneuron degeneration. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladhoff J. Fleischer B. Hara Y. Volk H.D. Seifert M. Immune privilege of endothelial cells differentiated from endothelial progenitor cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010;88:121–129. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta E.G. Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises, part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CF. Chang P.J. Huang Y.S. Sung Y.H. Huang C.C. Lin M.W. Liu Y.C. Tsai Y.C. Prolonged use of high-dose morphine impairs angiogenesis and mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in mice. Anesth. Analg. 2008;107:686–692. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817e6719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapergue B. Mohammad A. Shuaib A. Endothelial progenitor cells and cerebrovascular diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;83:349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara–Hernandez R. Lozano–Vilardell P. Blanes P. Torreguitart–Mirada N. Galmés A. Besalduch J. Safety and efficacy of therapeutic angiogenesis as a novel treatment in patients with critical limb ischemia. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2010;24:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Liu H. Jiao J. Liu H. Bergeron A. Dong J.F. Zhang J. changes in circulating human endothelial progenitor cells after brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:936–943. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D. Qu C. Goussev A. Jiang H. Lu C. Schallert T. Mahmood A. Chen J. Li Y. Chopp M. Statins increase neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, reduce delayed neuronal death in the hippocampal CA3 region, and improve spatial learning in rat after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1132–1146. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo C.L. Chen X.P. Yang R. Sun Y.X. Li Q.Q. Bao H.J. Cao Q.Q. Ni H. Qin Z.H. Tao L.Y. Cathepsin B contributes to traumatic brain injury-induced cell death through a mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:2847–2858. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng Y.S. Choi H.J. Kwon J.Y. Park Y.W. Choi K.S. Min J.K. Kim Y.H. Suh P.G. Kang K.S. Won M.H. Kim Y.M. Kwon Y.G. Endothelial progenitor cell homing: prominent role of the IGF2-IGF2R-PLCbeta2 axis. Blood. 2009;113:233–243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahooti S. Graesser D. Patil S. Newman P. D G. Mak T. Madri J.A. PECAM-1 (CD31) expression modulates bleeding time in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;157:75–81. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64519-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.J. Grimwood P.D. Morris R.G. Synaptic plasticity and memory: an evaluation of the hypothesis. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;23:649–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh T.K. Vin R. Noble L. Yamakani I. Fernyak S. Faden A.I. Traumatic brain injury in the rat: characterization of a lateral fluid percussion model. Neuroscience. 1989;28:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C.L. Siegel E. Barlogie B. Cotter–Fox M. Lin P. Fassas A. Zangari M. Anaissie E. Tricot G. Mobilization of CD34+ cells in elderly patients (>/=70 years) with multiple myeloma: influence of age, prior therapy, platelet count and mobilization regimen. Br. J. Haematol. 2003;120:413–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murasawa S. Asahara T. Endothelial progenitor cells for vasculogenesis. Physiology. 2005;20:36–42. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi C.T. Asavaritikrai P. Teng R. Jia Y. Role of erythropoietin in the brain. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007;64:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S. Makino H. Nagumo A. Sugisawa T. Fujimoto M. Kishimoto I. Miyamoto Y. Kikuchi–Taura A. Soma T. Taguchi A. Yoshimasa Y. Circulating CD34-positive cell number is associated with brain natriuretic peptide level in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:157–158. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardanaud L. Yassine F. Dieterlen–Lievre F. Relationship between vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and hemopoiesis during avian ontogeny. Development. 1989;105:473–485. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira A.C. Huddleston D.E. Brickman A.M. Sosunov A.A. Hen R. Mckhann G.M. Sloan R. Gage F.H. Brown T.R. Small S.A. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:5638–5643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettus E.H. Wright D.W. Stein D.G. Hoffman S.W. Progesterone treatment inhibits the inflammatory agents that accompany traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2005;1049:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufaihah A.J. Haider H.K. Heng B.C. Ye L. Tan R.S. Toh W.S. Tian X.F. Sim E.K. Cao T. Therapeutic angiogenesis by transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived CD133+ endothelial progenitor cells for cardiac repair. Regen. Med. 2010;5:231–244. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed I. Stein D.G. Progesterone as a neuroprotective factor in traumatic and ischemic brain injury. Prog. Brain Res. 2009;175:219–237. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senegaglia A.C. Barboza L.A. Dallagiovanna B. Aita C.A. Hansen P. Rebelatto C.L. Aguiar A.M. Miyague N.I. Shigunov P. Barchiki F. Correa A. Olandoski M. Krieger M.A. Brofman P.R. Are purified or expanded cord blood-derived CD133+ cells better at improving cardiac function? Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2010;235:119–129. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrokhi N. Khaksari M. Soltani Z. Mahmoodi M. Nakhaee N. Effect of sex steroid hormones on brain edema, intracranial pressure, and neurologic outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010;88:414–421. doi: 10.1139/y09-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear D.A. Galani R. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Progesterone protects against necrotic damage and behavioral abnormalities caused by traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2002;178:59–67. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D.G. Progesterone exerts neuroprotective effects after brain injury. Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellos K. Langer H. Gnerlich S. Panagiota V. Paul A. Schönberger T. Ninci E. Menzel D. Mueller I. Bigalke B. Geisler T. Bültmann A. Lindemann S. Gawaz M. Junctional adhesion molecule A expressed on human CD34+ cells promotes adhesion on vascular wall and differentiation into endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:1127–1136. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.204370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z. Han D. Sun B. Qiu J. Li Y. Li M. Zhang T. Yang Z. Heat stress preconditioning improves cognitive outcome after diffuse axonal injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1695–1706. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper O.M. Capla J.M. Galiano R.D. Ceradini D.J. Callaghan M.J. Kleinman M.E. Gurtner G.C. Adult vasculogenesis occurs through in situ recruitment, proliferation, and tubulization of circulating bone marrow-derived cells. Blood. 2005;105:1068–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thau–Zuchman O. Shohami E. Alexandrovich A.G. Leker R.R. Vascular endothelial growth factor increases neurogenesis after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F. Liang P.H. Li L.Y. Inhibition of endothelial progenitor cell differentiation by VEGI. Blood. 2009;113:5352–5360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlandingham J.W. Cekic M. Cutler S.M. Washington E.R. Johnson S.J. Miller D. Stein D.G. Progesterone and its metabolite allopregnanolone differentially regulate hemostatic proteins after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1786–1794. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter D.H. Rittig K. Bahlmann F.H. Kirchmair R. Silver M. Murayama T. Nishimura H. Losordo D.W. Asahara T. Isner J.M. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;105:3017–3024. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018166.84319.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Zhang S. Rabinovich B. Bidaut L. Soghomonyan S. Alauddin M.M. Bankson J.A. Shpall E. Willerson J.T. Gelovani J.G. Yeh E.T. Human CD34+ cells in experimental myocardial infarction: long-term survival, sustained functional improvement, and mechanism of action. Circ. Res. 2010;106:1904–1911. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Zhang Z. Wang Y. Zhang R. Chopp M. Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke. 2004;35:1732–1737. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000132196.49028.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.W. Bauer M.E. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Serum progesterone levels correlate with decreased cerebral edema after traumatic brain injury in male rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:901–909. doi: 10.1089/089771501750451820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.W. Kellermann A.L. Hertzberg V.S. Clark L. Frankel M. Goldstein F.C. Salomone J.P. Oldsterin F.C. Salomone J.P. Dent L.L. Harris O.A. Ander D.S. Lowery D.W. Patel M.M. Denson D.D. Gordon A.B. Wald M.M. Gupta S. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007;49:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing C. Lee S. Kim W.J. Wang H. Yang Y.G. Ning M. Wang X. Lo E.H. Neurovascular effects of CD47 signaling: promotion of cell death, inflammation, and suppression of angiogenesis in brain endothelial cells in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:2571–2577. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Mahood A. Chopp M. Emerging treatments for traumatic brain injury. Expert. Opin. Emerg. Drugs. 2009a;14:67–84. doi: 10.1517/14728210902769601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Mahood A. Chopp M. Angiogenesis, neurogenesis and brain recovery of function following injury. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2010;11:298–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Qu C. Mahood A. Liu Z. Ning R. Li Y. Kaplan D.L. Schallert T. Chopp M. Delayed transplantation of human marrow stromal cell-seeded scaffolds increases transcallosal neural fiber length, angiogenesis, and hippocampal neuronal survival and improves functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2009b;1263:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S. Zhang H.T. Zhang P. Luo J. Chen Z.Z. Jang X.D. Xu R.X. Functional endothelial progenitor cells derived from adipose tissue show beneficial effect on cell therapy of traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2010;473:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. Feng F. The potential of statin and stromal cell-derived factor-1 to promote angiogenesis. Cell Adh. Migr. 2008;2:254–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Xiong Y. Mahmood A. Meng Y. Qu C. Schallert T. Chopp M. Therapeutic effects of erythropoietin on histological and functional outcomes following traumatic brain injury in rats are independent of hematocrit. Brain Res. 2009;19:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.G. Chopp M. Neurorestorative therapies for stroke: Underlying mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:491–500. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]