Abstract

Aims

To describe: 1) our cohort of patients diagnosed with NCPH in a HIV academic clinic in North America, and 2) longitudinal follow-up and outcomes of patients following NCPH diagnosis.

Study design

Retrospective case series.

Place and Duration of Study

Owen clinic, University of California, San Diego, United States, between October 1990 and December 2010.

Methodology

We describe a cohort of patients diagnosed with NCPH in a HIV academic clinic with emphasis on their follow-up and outcomes after NCPH diagnosis.

Results

During the study period, eight HIV-infected men were diagnosed with NCPH. All patients were exposed to Didanosine (ddI) for a median of 37 months. One patient died soon after NCPH diagnosis due to a condition unrelated to NCPH. The other seven patients have received B-blocker therapy and annual esophago-gastro-duodenectomy screenings with banding of esophageal varices when indicated and remain still alive. Three patients were on ddI at the time of NCPH diagnosis. In one patient ddI was discontinued shortly after NCPH diagnosis. The other two patients continued to use ddI after NCPH diagnosis and developed recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the subsequent 2 years, requiring revascularization interventions. The four patients that were already off ddI at the time of NCPH diagnosis have been followed for a median of 6 years. These four patients remained minimally symptomatic for up to 16 years of follow-up from NCPH diagnosis.

Conclusion

When ddI was discontinued before portal hypertension was clinically apparent the progression of NCPH appeared to subside without major clinical complications.

Keywords: Noncirrhotic portal hypertension, HIV, didanosine

1. INTRODUCTION

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is a rare but increasingly recognized cause of liver morbidity and mortality among otherwise well controlled HIV patients (Maida et al., 2006, 2008; Mallet et al., 2007; Arey et al., 2007; Garvey et al., 2007; Sandrine et al., 2007; Saifee et al., 2008; Mendizabal et al., 2009; Cesari et al., 2010; Vispo et al., 2010). Its potential association with chronic antiretroviral use was first described in 2006 (Maida et al., 2006). The exact mechanisms that cause HIV-related NCPH are unknown (Cesari et al., 2010; Vispo et al., 2011). The main risk factor for development of HIV-related NCPH is exposure to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), in particular the purine analogue didanosine (ddI) (Kovari et al., 2009; Young et al., 2011; Cotte et al., 2011). It has been proposed that purine analogues could interfere with proinflammatory signaling molecules ATP and ADP in vascular endothelial cells that coupled to an acquired thrombophilic condition which result in progressive thrombosis of distal portal vein branches (Goicoechea and McCutchan, 2008; Vispo et al., 2011) that leads to variables degrees of increased intra-hepatic pressure (Chang, et al., 2009). The histological hallmark of HIV-related NCPH is the absence of bridging cirrhosis with paucity of portal veins along with focal fibrous obliteration of small portal veins (Schiano et al., 2007; Vispo et al., 2010). These vascular changes could result in some cases in prominent areas of hepatocyte regeneration that give the appearance of nodular regenerative hyperplasia (Mallet et al., 2007).

Although, in January 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a warning about ddI treatment and risk of HIV-related NCPH (Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm199169.htm) many chronically HIV-infected patients have prior ddI exposure and may be at risk for NCPH. Furthermore, little is known about the long-term prognosis of HIV-infected patients after NCPH diagnosis (Vispo, et al. 2010). Thus, this study aimed to describe: 1) our cohort of patients diagnosed with NCPH in an academic HIV clinic in the United States, and 2) longitudinal follow-up and outcomes of patients following NCPH diagnosis.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

We assembled a retrospective case series of HIV-infected adults diagnosed with NCPH at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), Owen Clinic. The study was approved by the UCSD Human Research Protection Program. All patients upon Owen Clinic enrollment provided written informed consent for the collection of data relevant to their clinical care and subsequent analysis. This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The case definition required: (1)portal hypertension defined as the presence of esophageal varices or portal gastropathy seen during esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) and/or abdominal computer tomography (CT) showing splenomegaly (>12cm measured craniocaudally at the level of the left midclavicular line ) plus esophageal /gastric varices and/or paraumbilical vein recanalization; 2) absence of other known causes of liver disease, including: active hepatitis B (negative quantitative Hepatitis B DNA and surface antigen) or C (negative antibody and RNA), hemochromatosis, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, alcohol abuse and no toxic exposure (vitamin A, copper sulphate, vinyl chloride monomer, thorium sulphate, Spanish toxic oil, arsenic salts or azathioprine)as described elsewhere (Mallet et al., 2007); and 3) absence of cirrhosis on liver histopathology. Electronic medical records of identified patients were reviewed to abstract information regarding demographic characteristics, relevant clinical, laboratory and histopathology data.

Liver biopsies were additionally reviewed by an independent pathologist with particular attention to the portal vasculature. Patients diagnosed with NPCH underwent prothrombotic work up that included: lupus anticoagulant, IgG and IgM anti-phospholipid antibodies, anti-thrombin III, total and activated levels of protein C and S, and G1691A factor V mutations.

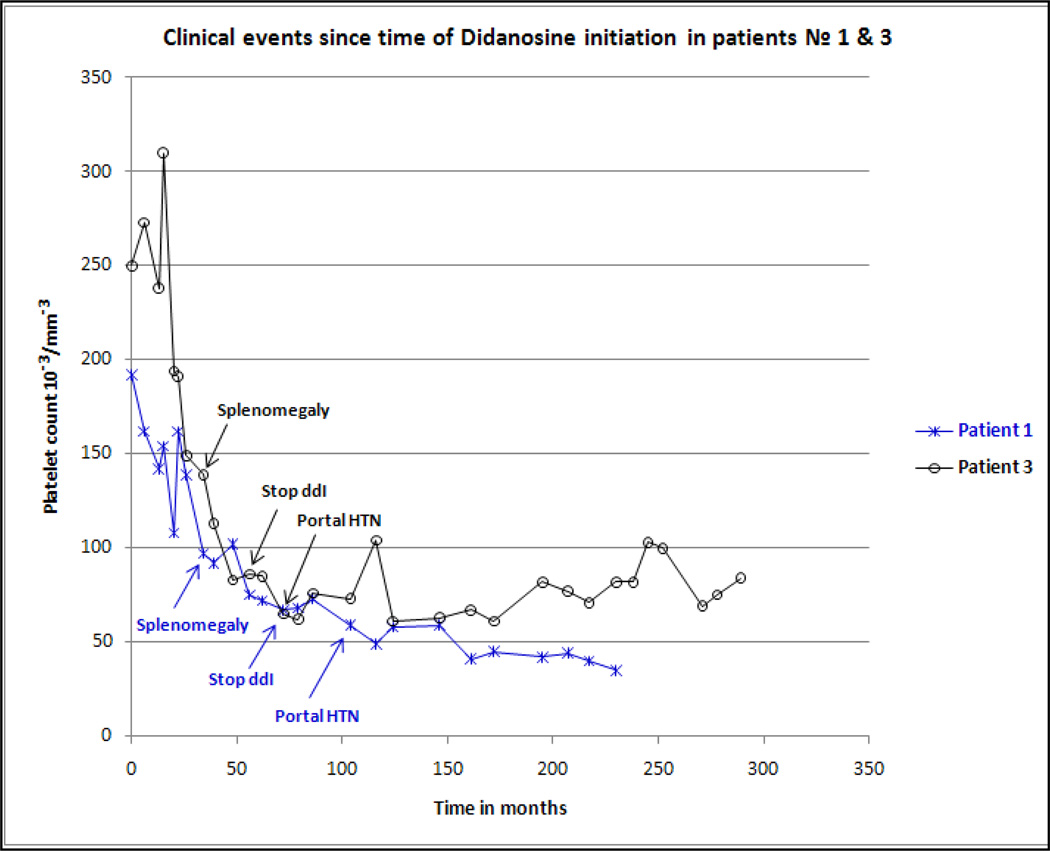

Graphics displaying longitudinal course of platelet count with attention to relevant NCPH clinical events were created using data of two patients with complete follow-up information from the time of HIV diagnosis until their last clinic visit (approximately 21 years interval). ‘Day 0’ of follow up time for the graphics was defined as the day when ddI therapy was initiated because ddI is the strongest risk factor implicated in development of HIV-related NCPH (Kovari et al., 2009; Young et al., 2011; Cotte et al., 2011).

3. RESULTS

Between 1 October 1990 and 31 December 2010, 8,460 HIV-infected patients were under care at the UCSD Owen clinic. Eight patients were diagnosed with NCPH during this period. The clinical reasons for which HIV providers initiated work up and discovered evidence of portal hypertension were: upper gastrointestinal bleeding or ascites (n=3); chronically fluctuating elevated transaminases (upper normal limit for aspartate and alanine aminotranferases were 40 and 41U/L, respectively) prompting abdominal CT evaluation (n=1); persistent unexplained thrombocytopenia (≤ 140,000 /mm3) and/or declining CD4 cell count with preserved CD4 cell percentage and consistently undetectable HIV viral load (prompting abdominal CT evaluation to rule out splenic sequestration) (n=3); and incidental EGD finding of esophageal varices in patient undergoing evaluation for chronic dyspepsia and diarrhea (n=1).

All patients diagnosed with NCPH were found to have been exposed to 400mg/day of ddI for a median of 37 months (range: 24 to 66 months). Two patients had prior history of NRTI toxicity (hyperlactatemia, neuropathy and pancreatitis). All patients had at the time of diagnosis of NCPH: (1) thrombocytopenia, (2) normal albumin and (3) international normalized ratio (INR) (Table 1). All patients diagnosed with NCPH had normal prothrombotic work up. Two patients had CT evidence of intrahepatic portal thrombosis at diagnosis of portal hypertension.

Table 1.

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of HIV-infected patients with noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reason for clinical evaluation: |

Ascites | Cytopenias | Cytopenias & Splenomegaly |

Variceal bleed |

Cytopenias | Incidental on EGD |

Variceal bleed |

Transaminase elevation |

| Diagnosis of HIV | 1987 | 1987 | 1985 | 1992 | 1993 | 1991 | 2000 | 1991 |

| Diagnosis of portal hypertension Age (years)a/sex |

2005 41/Male |

2005 57/Male |

1995 45/ Male |

2003 41/Male |

2005 43/Male |

2006 45/Male |

2006 46/Male |

2009 60/Male |

| Race | White | White | White | Hispanic | Hispanic | White | White | White |

| HIV risk | MSM | MSM | MSM | MSM | MSM | MSM | MSM | MSM |

| CD4 cell count (cells/µl)a | 175 | 184 | 108 | 600 | 37 | 45 | 241 | 457 |

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/ml)a | <50 | <50 | <400 | <75 | >100,000 | 52,000 | <50 | <48 |

| Antiretroviral regimena | ABC + TDF +SQV/r |

TZV+TDF+ fAPV/r |

AZT + ddC | ddI +TDF+ viramune |

Offb | ddI + TDF + fAPV/r+ MRV |

ddI + ABC + EFV |

3TC + ETV +RAL + DRV/r |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)a | 22.5 | 20.7 | 23.5 | 22.5 | 23.1 | 23.4 | 23.9 | 23.7 |

| Time to ddI exposure (months) | 36 | 60 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 24 | 66 | 36 |

| Prior NRTI side effects | Neuropathy Hyperlactatemia |

No | no | no | no | no | no | Neuropathy pancreatitis |

| Laboratory at diagnosis: | ||||||||

| AST (IU/ml) | 27 | 47 | 50 | 32 | 69 | 63 | 48 | 61 |

| ALT (IU/ml) | 24 | 57 | 44 | 35 | 50 | 86 | 34 | 75 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/ml) | 48 | 95 | 86 | 253 | 220 | 164 | 89 | 63 |

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 3.5 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 4 | 4 | 4.3 | 4.1 |

| INR | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| White blood cell count (×10−3/mm3) | 4.9 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 6.3 | |

| Platelet count (/mm3) | 47,000 | 61,000 | 80,000 | 136,000 | 67,000 | 113,000 | 98,000 | 124,000 |

| Liver biopsy: | Paucity distal terminal portal veins with focal sinusoidal fibrosis |

Focal sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltrate |

Normal liver architecture |

Paucity distal terminal portal veins. |

Subtle thickening & compression liver cells with sinusoidal dilatation |

Subtle nodular architecture with thickening & compression liver cells. Focal sinusoidal fibrosis. |

Focal sinusoidal fibrosis. |

Minimal portal inflammation and no evidence of fibrosis. |

| Follow up events: | ||||||||

| Subsequent variceal bleed | No | No | No | yes | no | yes | no | No |

| Subsequent ascites | No | No | No | yes | no | yes | yes | No |

| Subsequent portal thrombosis | No | yes | Yes | no | no | yes | no | No |

| Death | No | No | No | no | yes | no | no | no |

| Follow up time after portal hypertension diagnosis in years |

6 | 6 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 2 |

= Results/ medications displayed are at the time of noncirrhotic portal hypertension diagnosis.

= Patient self-discontinued all his antiretrovirals 2 months prior diagnosis of noncirrhotic portal hypertension.

EGD= esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy, MSM= Men who have sex with men, NRTI= nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor, AST= aspartate aminotransferase, ALT= alanine amotranferase, INR=international normalized ratio, ABC= Abacavir, TDF=Tenofovir, SQV=Saquinavir, r=ritonavir, ddI= Didanosine, fAPV= Fosamprenavir, AZT=Zidovudine, ddC= Zalcitabine, TZV = trizivir, MRV=Maraviroc, EFV=Efavirenz, 3TC=Lamivudine, ETV=Etravirine, RAL=Raltegravir, DRV=Darunavir, r=Ritonavir as a booster agent.

Patients were followed for a median time of 6 years (range: 1–16 years) after the diagnosis of portal hypertension. One patient (№ 5, Table 1) died within 1 year of NCPH diagnosis. At the time of death the patient had declined antiretroviral therapy and the cause of death was considered unrelated to NCPH. The other seven patients have received B-blocker therapy and annual EGD screenings with banding of esophageal varices when indicated. Three patients (№ 4, № 6 and № 7, Table 1) were on ddI at the time of NCPH diagnosis. Two patients (№ 4 and № 6, Table 1) continued ddI after being diagnosed with NCPH and developed recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the subsequent 2 years.

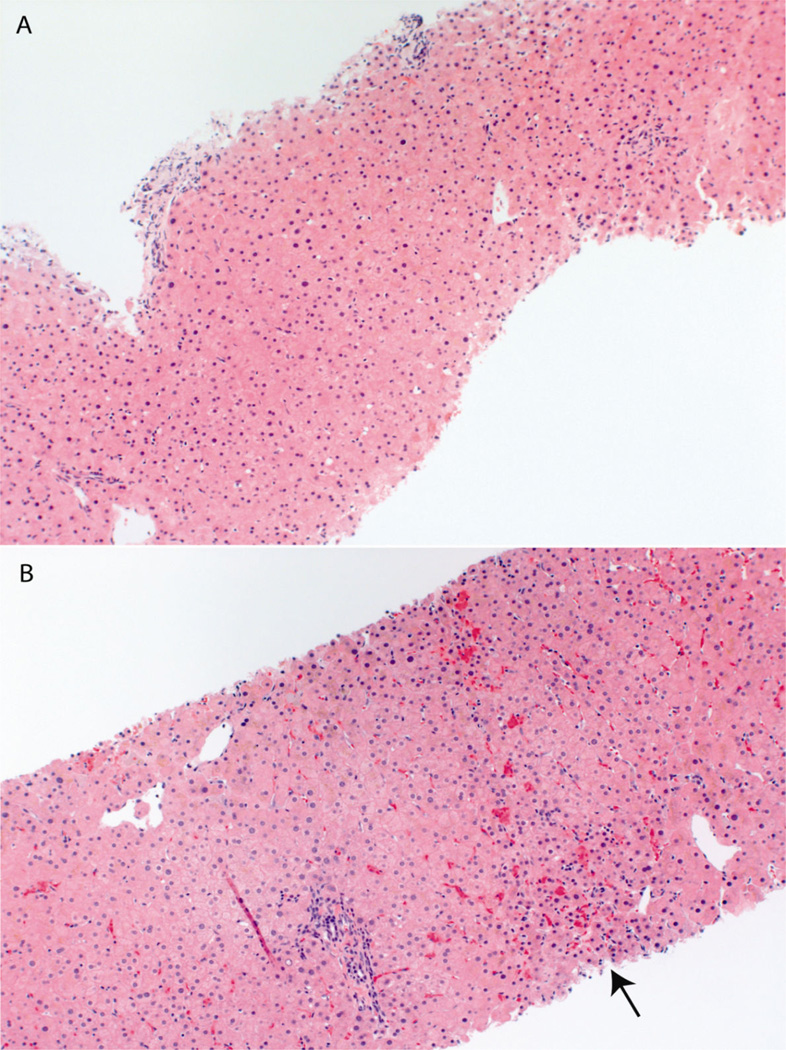

One required surgical hepatorenal shunt and remains alive six years after surgery (patient № 4, Table 1). The other patient had three transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placements (TIPS) but 2 years after his last TIPS procedure is awaiting a liver transplant due to severe nodular regenerative disease (patient № 6, Table 1). Four patients (№ 1, № 2, № 3, and № 8, Table 1) were already off ddI at the time of NCPH diagnosis, among them we had approximately 21 years of complete follow-up data from time of HIV diagnosis until now in two patients (№ 1 & № 3, Table 1). Both patients were noted to have subtle palpable splenomegaly 39 months after ddI initiation. Patients № 1 and № 3 discontinued ddI after 72 and 53 months of daily treatment, respectively; and before their portal hypertension was clinically recognized (Figure 1). In addition, Patient № 3 had paired liver biopsies five years apart. On initial liver histological examination Patient № 3 had intact hepatic architecture with minimal lobular activity and no appreciable portal inflammation or interface activity (Figure 2, panel A). Five years later, liver histology showed areas of centrilobular hepatocytes atrophy imparting a vaguely nodular appearance (Figure 2, panel B). This patient remains minimally symptomatic after 16 year of portal hypertension diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal evolution of platelet count and relevant clinical events following Didadonise initiation using data of patient № 1 and 3 (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Liver biopsy from patient № 3. (A) At time of noncirrothic portal hypertension diagnosis, with relatively normal liver architecture. (B) Histology 5 years after noncirrhotic portal hypertension diagnosis. The arrow shows some patchy centrilobular hepatocyte atrophy imparting a vaguely nodular appearance.

4. DISCUSSION

This study describes eight patients diagnosed with NCPH during the last twenty years in an academic HIV clinic in the United States, with emphasis in longitudinal follow-up and outcomes.

The largest case series of HIV-related NCPH comprises thirteen patients (12). The low number of cases reported in the literature needs to be interpreted with caution because the prevalence of asymptomatic or early stages of HIV patients with NCPH is likely higher than currently reported for the following reasons. First, there are no laboratories or clinical markers of early pathogenic events and the duration of subclinical lead time is unknown. Second, the minimal necessary exposure duration to the putative risk factor (such as ddI) is also unknown. Third, liver biopsy may not be performed to confirm cirrhosis when patients present with portal hypertension and have risk factors such as viral hepatitis or alcohol abuse. However, NCPH may appear superimposed in patients with underlying liver disease (Vispo, et al. 2008). Development of portal hypertension in the absence of impaired synthetic function should triggered consideration of a liver biopsy to exclude coexistent NCPH.

The observations in our two patients with at least 14 years of complete follow-up from ddI initiation suggest that once NCPH is clinically manifest the structural damage is irreversible. However, ddI discontinuation appeared to slow down disease progression of NCPH (Figure 1). This is consistent with a prior report (Maida et al., 2008) that showed improvement in liver enzymes and symptoms of patient with NCPH in the 12 months following ddI discontinuation but without significant change in the liver fibrosis scores measured using transient elastography. The survival rate in our cohort is also consistent with a long-term observation of a NCPH cohort in HIV negative individuals that underwent surgical revascularization and reported a five year survival of 90%, reflecting the relatively static nature of this condition if the offender agent is discontinued (Kingham et al., 1981). We observed that two of our patients had clinically apparent splenomegaly at least 2 years before their portal HTN was diagnosed. The delay in recognition of portal hypertension was likely due to lack of clinical awareness of NCPH among HIV clinicians in the prior decade.

We recognized that our study has an important diagnostic workup bias, reflecting the fact that patients with ddI exposure were more likely to be investigated than those without ddI exposure in particular after HIV-related NCPH was recognized in 2006 (Ransohoff and Feinstein, 1978). However, diagnosis of HIV-related NCPH is often late when life-threatening manifestations such as bleeding of esophageal varices occur. Our intention is to increase clinical awareness among HIV providers of the importance of early recognition of NCPH. Prompt diagnosis and discontinuation of offender agent (such as ddI) could minimize morbidity as most patients who did not have esophageal bleeding in our series have remained minimally symptomatic for up to 16 years of follow-up from NCPH diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the by the UCSD Center for AIDS Research (AI 36214) and the CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (AI067039-01A1). We wish to thank Susan McQuillen for clinical and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

REFERENCES

- 2010 Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsand Providers/ucm199169.htm.

- Arey B, Markov M, Ravi J, Prevette E, Batts K, Nadir A. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of liver as a consequence of ART. Aids. 2007;21:1066–1068. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280fa81cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Schiavini M, Marchetti G, et al. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension in HIV-infected patients: a case control evaluation and review of the literature. AIDS Patient Care STD. 2010;24:697–703. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PE, Miquel R, Blanco JL, et al. Idiopathic portal hypertension in patients with HIV infection treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1707–1714. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotte L, Benet T, Billioud C, et al. The role of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in nodular regenerative hyperplasia in HIV-infected patients: A case control study. J Hepatol. 2011;54:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey LJ, Thomson EC, Lloyd J, Cooke GS, Goldin RD, Main J. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is a new cause of chronic liver disease in HIV-infected patients. Aids. 2007;21:1494–1495. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281e7ed64. Response to Mallet et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea M, McCutchan A. Abacavir and increased risk of myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2008;372:803–804. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingham JG, Levison DA, Stansfeld AG, Dawson AM. Non-cirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension: A long term follow-up study. Q. J. Med. 1981;50:259–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovari H, Ledergerber B, Peter U, et al. Association of noncirrhotic portal hypertension in HIV-infected persons and antiretroviral therapy with didanosine: a nested case-control study. Clin. Infect Dis. 2009;49:626–635. doi: 10.1086/603559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maida I, Garcia-Gasco P, Sotgiu G, et al. Antiretroviral-associated portal hypertension: a new clinical condition? Prevalence, predictors and outcome. Antivir. Ther. 2008;13:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maida I, Nunez M, Rios MJ, et al. Severe liver disease associated with prolonged exposure to antiretroviral drugs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:177–182. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221683.44940.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet VO, Varthaman A, Lasne D, et al. Acquired protein S deficiency leads to obliterative portal venopathy and to compensatory nodular regenerative hyperplasia in HIV-infected patients. Aids. 2009;23:1511–1518. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832bfa51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet V, Blanchard P, Verkarre V, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is a new cause of chronic liver disease in HIV-infected patients. Aids. 2007;21:187–192. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280119e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendizabal M, Craviotto S, Chen T, Silva MO, Reddy KR. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension: another cause of liver disease in HIV patients. Ann. Hepatol. 2009;8:390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff DF, Feinstein AR. Problems of spectrum and bias in evaluating the efficacy of diagnostic tests. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978;299:926–930. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197810262991705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifee S, Joelson D, Braude J, et al. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;6:1167–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrine PF, Sylvie A, Andre E, Abdoulaye D, Bernard L, Andre C. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: a new serious antiretroviral drugs side effect? Aids. 2007;21:1498–1499. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328235a54c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiano TD, Kotler DP, Ferran E, Fiel MI. Hepatoportal sclerosis as a cause of noncirrhotic portal hypertension in patients with HIV. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2536–2540. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vispo E, Maida I, Barreiro P, Moreno V, Soriano V. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding may unmask didanosine-associated portal hepatopathy in HIV/HCV co-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9:440–444. doi: 10.1310/hct0906-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vispo E, Morello J, Rodriguez-Novoa S, Soriano V. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension in HIV infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2011;24:12–18. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283420f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vispo E, Moreno A, Maida I, et al. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension in HIV-infected patients: unique clinical and pathological findings. Aids. 2010;24:1171–1176. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283389e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young J, Klein MB, Ledergerber B. Noncirrhotic portal hypertension and didanosine: a re-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:154–155. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]