Abstract

Very little is known on white‐collar crime and how it differs to other forms of offending. This study tests the hypothesis that white‐collar criminals have better executive functioning, enhanced information processing, and structural brain superiorities compared with offender controls. Using a case‐control design, executive functioning, orienting, and cortical thickness was assessed in 21 white‐collar criminals matched with 21 controls on age, gender, ethnicity, and general level of criminal offending. White‐collar criminals had significantly better executive functioning, increased electrodermal orienting, increased arousal, and increased cortical gray matter thickness in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, somatosensory cortex, and the temporal‐parietal junction compared with controls. Results, while initial, constitute the first findings on neurobiological characteristics of white‐collar criminals. It is hypothesized that white‐collar criminals have information‐processing and brain superiorities that give them an advantage in perpetrating criminal offenses in occupational settings. Hum Brain Mapp, 2012. © 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: antisocial, ventromedial, inferior frontal, temporal‐parietal, somatosensory, orienting, arousal, electrodermal

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade an increasing body of research has documented neurocognitive [Seguin et al., 2009], psychophysiological [Gao et al., 2010; Patrick, 2008; Pine et al., 1998], brain structural/function [Glenn et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2008; Sterzer et al., 2005; Yang and Raine, 2009], neurochemical [Coccaro and Lee, 2010; Siever 2008; Van Goozen et al., 2007], and genetic [Caspi and Moffitt, 2006] processes in the putative etiology of antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior. Nevertheless, a significant gap in the emerging field of neurocriminology consists of research on subtypes of criminal offenders. In particular, there has been no research on the neuroimaging, psychophysiological, or neuropsychological correlates of white‐collar criminals.

White‐collar crime has been defined quite broadly as “economic offenses committed through the use of some combination of fraud, deception, or collusion” [Wheeler et al., 1982; p. 642]. While white‐collar crime was recently conceived as elite, upper world, and upper class offending [Coleman, 1989], more recent research has shown that white‐collar offenders are generally middle to lower‐middle class, do not specialize in one form of crime, and also perpetrate street crimes [Weisburd et al., 2001]. In explaining white‐collar crime, criminologists have focused on organizational norms, culture, managerial leadership, decision making, compensation, and incentives [Langton and Leeper‐Piquero, 2007]. In contrast, little or no attention has been be paid to differences between blue‐collar street offenders and white‐collar offenders. White‐collar offenders however have been viewed as engaging in a careful calculation of the both costs and benefits of offending [Paternoster and Simpson, 1993], although this has not been pursued empirically.

Given prior research revealing neurobiological correlates of antisocial and criminal behavior, it is hypothesized that neurobiological characteristics may also exist for white‐collar offending. Rather than conceiving these characteristics as deficits, they more likely aid them in accommodating the structure, function, and culture of an organization, allowing white‐collar offenders to engage in elaborate calculations that consider a wide‐range of factors. Given the evidence that white‐collar crime is both a reaction and adaptation to a range of organizational and structural variables [Schlegel and Weisburd, 1992], and given that there is a rationality to this kind of offending that requires careful calculations, we hypothesize that white‐collar offenders have superior executive functioning and attentional functioning compared to controls, as well as enhanced brain cortical thickness, particularly in brain areas that play a role in decision‐making, attention, and social perspective‐taking and which could confer an advantage in their reaction and adaptation to organizations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eighty‐seven participants (75 male, 12 female) were recruited from five temporary employment agencies [Raine et al., 2009]. Exclusion criteria included: age under 21 or over 46, non‐fluency in English, history of epilepsy, claustrophobia, pacemaker, ostensible neurological abnormality, and metal implants. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was approved by an institutional review board. This community recruitment strategy is novel, but has the advantage that it samples individuals at high socioeconomic risk, with an eight‐fold increase in the yield of those with psychopathy/antisocial personality [Raine et al., 2009].

Participants were classified as white‐collar criminals if they had committed white‐collar criminal offenses (see below). Using a case‐control design, 21 individuals who committed white‐collar criminal offenses were matched with 21 participants who had never perpetrated a white‐collar crime on age, gender, and ethnicity. In addition, in order to control for non‐white‐collar criminal offenses that the white‐collar criminals had also committed, the two groups were matched on total non‐white‐collar crime scores (see below). Results of this matching process are presented in Table I, along with group means on IQ, social class, and official crime. Social class was measured using Hollingshead's Index of Social Position [Hollingshead, 1975]. Handedness was assessed on a dimensional scale as used in our prior research, with higher scores indicating greater right‐handedness [Raine et al., 2011].

Table I.

Group comparisons between white‐collar criminals (N = 21) and controls (N = 21) on the matching variables (age gender, ethnicity, blue collar crime), as well as IQ, socio‐economic status, and criminal arrests/convictions

| White‐collar | Controls | Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30.38 (7.95) | 29.38 (6.73) | t = −0.44 | .66 |

| Gender (male/female) | 18 male 4 female | 18 male 4 female | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 9 | 9 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| African‐American | 8 | 8 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 2 | ||

| Asian | 2 | 2 | ||

| Blue collar crime | 10.42 (7.24) | 11.81 (5.72) | t = 0.68 | .49 |

| Arrests | 9 of 21 (42.9%) | 8 of 21 (38.1%) | χ2 = .09 | .75 |

| Convictions | 5 of 21 (23.8%) | 7 of 21 (33.3%) | χ2 = 0.46 | .50 |

| Social class | 34.4 (10.53) | 35.24 (11.79) | t = 0.24 | .81 |

| Handedness | 35.4 (8.48) | 31.28 (12.03) | t = 1.36 | .19 |

| Intelligence | ||||

| Verbal | 98.43 (14.16) | 95.29 (15.21) | t = 0.69 | .49 |

| Performance | 100.24 (21.38) | 95.24 (15.33) | t = 0.87 | .38 |

| Total IQ | 98.95 (17.14) | 94.52 (14.93) | t = 0.0.89 | .38 |

Criminal Offending

White and blue collar crime was assessed using a 50‐item adult extension of the self‐report National Youth Survey [Raine, et al., 2000], assessing property, violence, sex, and drug offenses. White‐collar crime was defined by the following items: used computers illegally to gain money or valuable information, cheated or conned a person, business, or government for gain; obtained unemployment or sickness benefit by telling lies, stolen supplies from work, using a stolen check or credit card, and lied about income on a tax return [Barnett, 2000]. Blue‐collar crime was assessed based on all other criminal offenses. Each item was scored on a three‐point scale as follows: 0 (none), 1 (one to two occurrences) 2 (3 or more). Official (detected) crime was assessed from a search of Department of Justice criminal records, with total numbers of arrests and convictions coded for each participant [Raine et al., 2009]. Only two of the 21 white‐collar criminals had been charged with a white‐collar crime, in both cases for forgery. One individual had two charges and one conviction, while the other had four charges and two convictions.

To encourage both transparency and authenticity by subjects, a certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the Secretary of Health, pursuant to Section 303(a) of Public Health Act 42. Participants were informed that any information they might provide about uninvestigated crimes could not be subpoenaed by any United States federal, state, or local court. Participants were reminded of confidentiality during administration of the measure and the limits to the confidentiality certificate.

Neurocognitive Functioning

Executive functioning was assessed using the computerized version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; [Kongs et al., 2000]). Scores for categories achieved (the number of times a participant correctly sorted 10 consecutive cards), perseverative errors (the number of times cards in incorrect response were repeated), and correct responses (number of cards correctly classified) were computed.

Total IQ was estimated using four subtests (vocabulary, arithmetic, block design, and digit symbol) of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS‐R) [Wechsler, 1981]. Verbal IQ was estimated using vocabulary and arithmetic, while performance IQ was estimated using block design and digit symbol subtests.

Psychophysiological Assessment

Acquisition

Skin conductance was measured during both rest and orienting conditions. Participants were tested in a temperature‐controlled, light‐and sound‐attenuated psychophysiological recording laboratory. Bilateral skin conductance was recorded from the distal phalanges of the first and second fingers of the both hands [Scerbo et al., 1992] using Beckman Ag/AgCl electrodes of 1 cm diameter with physiological saline (0.9% NaCl) in Unibase as the electrolyte. Skin contact area was delineated using double‐sided adhesive masks with a hole of 1 cm diameter. Recordings were made using a Grass Model 7 polygraph (Quincy, MA) with a constant 0.5V potential across electrodes for direct recording of skin conductance [Venables and Christie, 1980]. Participants were instructed that after a 3‐min rest period they would hear a series of tones that would last about 5 min.

Orienting stimuli

Ten orienting stimuli were presented with interstimulus intervals randomized between 25 and 40 s, consisting of six 75‐dB tones of 1,000 Hz frequency, 25‐ms rise time, and 1‐s duration. These were followed by four more attentionally meaningful stimuli consisting of a reorienting stimulus (500 Hz tone of 75 dB intensity, 1‐s duration), a consonant‐vowel stimulus (“da”, 0.35‐s duration, 75‐dB intensity), one 90 dB pure tone (1‐s duration, 1,000 Hz frequency), and one 90‐dB white noise burst (1‐s duration, 5‐ms rise time).

Scoring

Orienting was assessed by the number of skin conductance responses (SCRs) >0.05 microsiemens in amplitude occurring within a latency window of 1–3 s post‐stimulus. Arousal was assessed by the number of nonspecific SC responses occurring during the 3‐min rest period (using the same amplitude criterion as for SCRs above), together with SC levels at the end of the rest period. Habituation was defined as the number of trials to give three consecutive nonresponses.

Neuroimaging

Acquisition

Structural MRI was conducted on a Philips S15/ACS scanner (Selton, Connecticut) with a 1.5 Tesla magnet. Following an initial alignment sequence of one midsaggital and four parasagittal scans (spin‐echo T1‐weighted image acquisition, TR = 600 ms, TE = 20 ms) to identify the AC‐PC plane, 128 3D T1‐weighted gradient‐echo coronal images (TR 34 ms, TE 12.4 ms, flip angle 35°, 1.7 mm slices, 256 × 256 matrix, FOV = 23 cm) were taken orthogonal to the AC‐PC line.

Image analysis

A series of previously detailed preparatory steps [Narr et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009] were applied to the MR data including the removal of extracortical tissue, the correction for inhomogeneities, head tilt and orientation, and placing the data into ICBM‐305 common stereotaxic space. Next, a fully automated partial volume classifier was applied to classify voxels into GM, white matter (WM) and CSF. Total intracranial volumes (excluding the pons and cerebellum) and volumes of each brain tissue compartment were estimated. Finally, a surface‐rendering algorithm was used to create a three‐dimensional model of the cortical surface for each individual [Narr et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009].

Cortical pattern matching

Thirty‐one sulcal landmarks were delineated manually in each hemispheric surface following previously validated protocols [Narr et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009] for which intra‐ and inter‐rater reliability has been established [Yang et al., 2009]. Cortical pattern matching methods were then applied to spatially relate homologous regions of the cortex between subjects that allows for measurement and comparison of cortical thickness at homologous locations in each individual [Narr et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009]. Next, the previously obtained tissue classified brain volumes were used to calculate the GM thickness at all spatially aligned hemispheric surface points within subjects and then compared between groups to provide spatially detailed maps indexing very local differences in cortical thickness across the brain.

Statistical Analyses

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to analyze the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task executive functioning measures. Repeated measures MANOVAs (group × hand) were used to analyze the left and right hand skin conductance data.

To address the hypothesis of group differences in cortical thickness, statistical analyses were conducted using the general linear model implemented in R (http://www.r-project.org) to identify regional changes in cortical thickness between groups while covarying for whole brain volume. Uncorrected two‐tailed probability values obtained from statistical tests conducted for each cortical surface point were color‐coded and displayed on the averaged cortical surface representations of the entire group to allow initial visualization of group differences.

Since comparisons were made at thousands of spatially correlated cortical locations, permutation tests with a threshold of P < 0.05 were applied to ensure that the overall pattern of effects in the uncorrected statistical maps could not have been observed by chance alone (Yang et al., 2009). Permutation testing was performed for each hemisphere and within 20 gyral regions obtained using the Laboratory of NeuroImaging Probabilistic Brain Atlas (LPBA40) [Shattuck, et al., 2008] (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/Atlases/LPBA40).

RESULTS

Neurocognitive Functioning

White‐collar criminals showed significantly better executive functioning. A single MANOVA conducted on categories completed, perseverative errors, and number correct showed a significant group effect, F(3,38) = 3.43, P = 0.026, eta2 = 0.21, with white‐collar criminals showing significantly better executive functioning than controls (see Table II). Specifically, white‐collar criminals demonstrated significantly higher scores on categories achieved (P < 0.027). White‐collar criminals also evidenced a trend towards reduced perseveration errors (P < 0.14, d = 0.47).

Table II.

Group comparisons on executive functioning and electrodermal measures of arousal, orienting, and habituation. Standard deviations are in parentheses

| White‐Collar Criminals | Controls | Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive functioning | 0.39 (0.97) | −0.08 (0.96) | F = 3.43 | 0.026 |

| Orienting | F = 3.55 | 0.038 | ||

| Left hand | 4.52 (2.90) | 2.71 (3.03) | ||

| Right hand | 3.86 (3.30) | 3.04 (3.18) | ||

| Habituation | F = 5.41 | 0.025 | ||

| Left hand | 5.81 (1.53) | 4.38 (1.65) | ||

| Right hand | 5.33 (1.77) | 4.57 (1.80) | ||

| Arousal | F = 5.73 | 0.022 | ||

| Spontaneous SCRs | 7.26 (6.96) | 2.60 (3.01) | ||

| SCLs | 4.88 (3.76) | 4.22 (2.70) |

Executive functioning represents a standardized score. SCRs (skin conductance response). SCLs (skin conductance levels in microsiemens). Orienting reflects number of skin conductance orienting responses. Higher habituation scores reflect more trials to habituation.

White‐collar criminals had nonsignificantly higher verbal IQ and performance IQ (see Table I). To assess whether this trend could account for the better executive functioning in white‐collar criminals, multivariate analyses on executive functioning measures were repeated after entering IQ as a covariate. Although IQ was a significant covariate (P < 0.0001), group differences on executive functioning remained significant, F(1,37) = 3.04, P = 0.041, eta2 = 0.20.

Arousal, Orienting, and Habituation

Arousal

White‐collar criminals showed significantly higher electrodermal arousal at rest compared with controls, F(1.36) = 5.73, P = 0.02. eta2 = 0.14. A MANOVA revealed a significant group × measure interaction (F(1,36) = 7.54, P = 0.009, eta2 = 0.17) indicated that the higher resting arousal was more accounted for by nonspecific skin conductance responses than by skin conductance levels (see Table II).

Orienting

White‐collar offenders gave significant more left and right hand skin conductance orienting responses (mean of left and right hand combined = 4.19, SD = 3.02) than controls (mean = 2.88, SD = 3.11), F(2,39) = 3.55, P = 0.038, eta2 = 0.15. While group differences tended to be stronger on the left hand (see Table II), this trend for a group x hand interaction was nonsignificant, F(1,40) = 4.06, P = 0.051, eta2 = 0.09, (see Table II).

Habituation

White‐collar criminals took longer to habituate to the orienting stimuli (5.6 trials averaging across hands, SD = 1.55) compared with controls (4.4 trials, SD = 1.72). A group × hand repeated measures MANOVA revealed a main effect for group, F(1,40) = 4.73, P = 0.036, eta2 = 0.11, and a group × hand interaction, F(1,40) = 5.41, P = 0.035, eta2 = 0.12. A breakdown of this interaction indicated that the sustained attention of the white‐collar offenders was stronger for the left hand (t = 2.90, df = 40, P = 0.006) compared with the right hand (t = 1.38, df = 40, P = 0.18).

Cortical Thickness

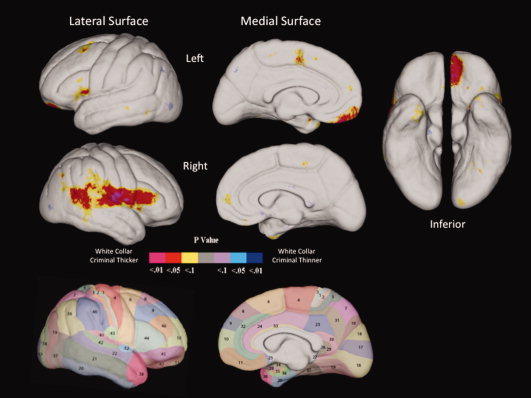

Maps of the uncorrected two‐tailed probability values for each cortical surface point for the lateral and medial surfaces of left and right hemispheres are shown in Figure 1 and allow initial visualization of group differences. It can be seen that in all cases white‐collar criminals have increased cortical thickness in multiple areas, with no evidence of reduced thickness.

Figure 1.

Results of cortical pattern matching analysis identifying group differences in left and right hemisphere cortical thickness throughout lateral, medial, and inferior surfaces, together with Brodmann maps of the corresponding regions. Warm colors (purple, red, yellow) indicate increased cortical thickness in white‐collar criminals. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Permutation‐corrected analyses on gyral areas indicated significant group differences in cortical thickness in white‐collar criminals in five main regions. Specifically, white‐collar criminals showed increased cortical thickness in the left ventromedial prefrontal cortex (P = 0.043; BA 11), the right inferior frontal gyrus (P = 0.038; BA 44), the right precentral gyrus (P = 0.036; BA 6), the right postcentral gyrus (P = 0.018; BAs 1,2,3), the right posterior superior temporal gyrus forming part of the temporal‐parietal junction (P = 0.03; BAs 41, 42, 22), and the inferior parietal region of the right temporal‐parietal junction (P = 0.03; BAs 39, 40, 43).

DISCUSSION

White‐collar criminals demonstrate better executive functions, increased and sustained orienting, increased arousal, and increased cortical thickness in multiple brain regions subserving decision‐making, social cognition, and attention. Results, while provisional, constitute the first findings on neurobiological characteristics of white‐collar criminals. Findings lend support to the hypothesis that white‐collar criminals, compared with other offenders, have enhanced cognitive and attentional functioning that place them at an advantage in committing offenses in the workplace.

White‐collar criminals had better executive functioning as assessed by a classic measure of this neurocognitive ability, the Wisconsin Card‐Sorting Task. This task measures concentration, planning, organization, cognitive flexibility in shifting strategies to achieve a goal, working memory, and the ability to inhibit impulsive responding [Kongs et al., 2000]. White‐collar offenders appear paradoxically to have the type of neurocognitive capacity and skills that would normally place them at a job performance advantage, a finding consistent with an extension of rational choice theory of white‐collar offending [Paternoster and Simpson, 1993].

At a psychophysiological level, white‐collar criminals also showed increased electrodermal arousal at rest compared with matched controls. This was most strongly indicated by spontaneous skin conductance responses which reflect ongoing cognitive processing and sustained attention [Crider, 2008]. They also gave large skin conductance responses to both neutral as well as attentionally meaningful auditory stimuli, including consonant‐vowel speech stimuli, indicating greater attentional processing. They additionally took more trials to habituate, indicating sustained attention to these auditory probes. Increased orienting has been associated with increased activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the temporal‐parietal junction, the supramarginal gyrus, and the amygdala, particularly in the right hemisphere [Williams et al., 2000, 2007]. Increased cortical thickness was observed in the first three of these right hemisphere regions in white‐collar criminals and may partly account for their heightened attentional processing to external stimuli.

At the level of brain structure, white‐collar offenders showed greater cortical thickness in five circumscribed areas compared to matched controls (see Fig. 1). First, they showed increased thickness in the right inferior frontal gyrus (BA 44). The inferior frontal gyrus has been implicated in a number of executive functions, particularly cognitive control and response inhibition. These functions include the ability to coordinate thoughts and actions in relation to internally generated goals, the ability to respond to changes in task demands, the ability to inhibit a dominant response, and the ability to resolve conflicting reasoning [Brass et al., 2005; Hampshire et al., 2010; Tsujii et al., 2010]. Recent research has increasingly documented localization of these inferior frontal functions to the right hemisphere [Brass et al., 2005; Chikazoe, 2010; Goghari and MacDonald, 2009; Hampshire et al., 2010; Shamay‐Tsoory et al., 2005]. This posterior region of the fronto‐lateral cortex also constitutes part of the inferior frontal junction, an area centrally involved in cognitive control systems, response inhibition, and task switching [Brass et al., 2005]. Taken together with findings of better executive functioning, increased cortical thickness in the inferior frontal gyrus and the inferior frontal junction is consistent with increased cognitive flexibility and regulatory control in white‐collar criminals compared with matched controls.

The second area of increased cortical thickness in white‐collar criminals constituted the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Brodmann area 11). This region has been associated with good decision‐making, sensitivity to the future consequences of one's actions, and the generation of skin conductance responses [Bechara et al., 1997, 2000]. This structural advantage is again broadly consistent with the better executive functioning, skin conductance orienting, arousal, and attention observed in white‐collar criminals. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is additionally involved in the monitoring of the reward value of stimuli, and learning and remembering what stimuli are rewarding [Kringelbach and Rolls, 2004]. Functional imaging studies have shown that it is the anterior region of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex that is specifically associated with abstract rewards, particularly money [Kringelbach and Rolls, 2004]. In contrast, less abstract, and more fundamental rewards (such as taste) are processed in the more posterior regions of this ventromedial area [Kringelbach, 2005]. White‐collar criminals had increased cortical thickness in the anterior but not posterior ventromedial region (see Fig. 1). As such, increased cortical thickness in the anterior region of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex gives rise to the hypothesis that white‐collar criminals are particularly driven by abstract monetary rewards as opposed to less abstract rewards.

A third area of increased cortical thickness consisted of the ventro‐lateral premotor area of the precentral gyrus (BA 6). This subregion is involved in monitoring performance and decision‐making, planning and programming of movements, and facilitating and inhibiting motor actions depending on the behavioral context [Buch et al., 2010; Pardo‐Vazquez et al., 2009]. In addition to these motor control functions, the premotor area has also been implicated in the ability to understand the intentions of others' actions [Iacoboni et al., 2005] and social perception [Lawrence et al., 2006]. The ventro‐lateral region of the premotor area also constitutes a part of the inferior frontal junction involved in response inhibition and task switching [Derrfuss et al., 2005]. While we had not anticipated group differences in this region and while such structural findings should consequently be treated with caution, they are nevertheless broadly consistent with the hypothesis of adept executive functioning and social cognition in white‐collar criminals.

A fourth area of increased cortical thickness consists of the inferior region of somatosensory cortex (BAs 1,2,3). The somatic marker hypothesis of decision‐making argues that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex receives information from the somatosensory cortex in which both past and present bodily states are continuously represented [Damasio, 1994]. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex in turn is argued to be an integral component of a neural emotional mechanism that uses somatic markers to guide good decision‐making [Bechara and Damasio, 2005]. Consequently, increased somatosensory cortical thickness combined with increased ventromedial thickness, increased electrodermal orienting, and better executive functioning may be broadly explicable in the context of the somatic marker theory that has recently been applied to economic decision‐making [Bechara and Damasio, 2005]. Unlike conventional criminal offenders who are hypothesized to have somatic marker deficits and poor decision‐making skills [Bechara et al., 1997; Damasio, 1994; Raine et al., 2000], white‐collar criminals may instead be characterized by relatively better decision‐making skills.

Fifth, white‐collar criminals compared to matched controls showed increased cortical thickness in a broad area of the temporal‐parietal junction that included the right posterior superior temporal gyrus (BA 41,42) and the right inferior parietal lobule (BA 39, 40, 43), including the angular gyrus (BA 39) and the supramarginal gyrus (BA 40). The right temporal‐parietal junction is centrally involved in both social cognition and orienting, including the ability to process social information, perspective‐taking, theory‐of‐mind, and executive control tasks 50,51. The temporal‐parietal junction is also involved in orienting, directing attention to external events of interest, and facilitating appropriate responses to these events [Decety and Lamm, 2007]. Because Brodmann areas 41 and 42 also constitute primary auditory cortex, increased cortical thickness in the temporal‐parietal junction may both help account for the better electrodermal orienting to auditory stimuli shown by white‐collar criminals, and lends support to the hypothesis that they may be characterized by better social perspective‐taking and the ability to read others which may place them at an advantage in an occupational context for the perpetration of white‐collar crimes.

Because the WCST has been traditionally viewed as reflecting dorsolateral prefrontal functioning, one might expect white‐collar criminals to show increased cortical thickness of this region. However, more recent functional imaging research on the WCST has delineated a much more complex neural circuit underlying task performance that extends well beyond dorsolateral prefrontal regions, involving a much broader fronto‐temporal‐parietal system. Specifically, the right orbitofrontal cortex (inhibition of previously acquired rules), the inferior frontal gyrus (executive working memory), and the temporal‐parietal junction (detection of errors and utilization of feedback) are all activated by the WCST, with such activation being predominantly in the right hemisphere [Lie et al., 2006]. The fact that white‐collar criminals demonstrated increased cortical thickness in all these right hemisphere cortical regions provides a degree of convergence between these cortical thickness increases and enhanced executive functioning in white‐collar offenders.

Limitations of this study should be clarified. First, the control group was matched with the white‐collar criminals on general criminal offending to control for the fact that white‐collar criminals also commit nonwhite‐collar crimes [Weisburd et al., 2001]. While it is critically important to conduct such a control for general level of offending, it remains to be seen how these two groups differ to non‐criminal controls. This initial study needs to be replicated and extended by examining a four group design (noncriminal controls, blue collar crime only, blue and white‐collar, white‐collar crime only) to further establish whether white‐collar criminals have brain superiorities compared to normal controls, although we recognize that such a complex design has never been undertaken to date even in the social sciences. Second and relatedly, it could be argued that rather than white‐collar criminals having structural and functional brain superiorities compared to controls, the criminal controls have diminished neurocognitive functioning and brain structure. Such a counter‐interpretation however cannot account for the fact that white‐collar criminals had an equivalent level of blue collar “street” criminal offending compared to controls; this should lead to the prediction that white‐collar offenders should show neurocognitive and brain deficits, yet this was not the case. Third, this study does not include white‐collar criminals who are convicted of major fraud or high‐profile crimes, and consequently findings cannot be generalized to these populations. Fourth and relatedly, the self‐report method for assessing white‐collar crime has inevitable limitations, although it also has a distinct advantage over official crime reports in accessing the “dark figure” of white‐collar crime. Fifth, prospective longitudinal studies are required to assess whether structural brain superiorities precede the onset of offending, or conversely whether the better executive functioning required of white‐collar crime results in later brain changes. Sixth, given the relatively robust finding of increased right ventromedial prefrontal cortical thickness in white‐collar criminals, future studies of these offenders could usefully extend neurocognitive testing to include measures more reflective of this neural region, and assess whether structure and function measures covary. Finally, while the observed neurocognitive, psychophysiological, and brain structural characteristics may make some individuals better equipped to perpetrate white‐collar offending in the workplace, these advantages do not confer criminality per se, as indicated by the fact that the control group with equal levels of blue collar crime lack these characteristics.

CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations, this initial study provides the first evidence of a neurobiological basis to white‐collar crime and a novel conceptual perspective on this societal problem. Theories of white‐collar offending must not only recognize the core antisocial behaviors in this group, but also the neurobiological trait characteristics which may confer an adaptive advantage to offenders in the workplace. These findings, while preliminary and limited by the nature of this high‐risk temporary employment agency sample, are broadly consistent with the idea that white‐collar criminals engage in a careful and rational calculation of both the costs and benefits of offending. Findings highlight the complexity of crime and raise the future challenge to forensic psychiatry, criminology, and the corporate world of extending these initial findings on white‐collar offenders to more serious offenders in financial institutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Bobier, Nicole Diamond, Kevin Ho, Lori Lacasse, Todd Lencz, Shari Mills, and Pauline Yaralian for assistance in data collection.

REFERENCES

- Barnett C ( 2000): The Measurement of White‐Collar Crime Using Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Data ( Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Justice, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio AR ( 2005): The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games Economic Behav 52: 336–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Damasio AR ( 2000): Emotion, decision making and the orbitofrontal cortex. Cerebral Cortex 10: 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR ( 1997): Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science 275: 1293–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass M, Derrfuss J, Forstmann B, von Cramon DY ( 2005): The role of the inferior frontal junction area in cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci 9: 314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch ER, Mars RB, Boorman ED, Rushworth MFS ( 2010): A network centered on ventral premotor cortex exerts both facilitatory and inhibitory control over primary motor cortex during action reprogramming. J Neurosci 30: 1395–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE ( 2006): Opinion ‐ Gene‐environment interactions in psychiatry: Joining forces with neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikazoe J ( 2010): Localizing performance of go/no‐go tasks to prefrontal cortical subregions. Current Opin Psychiatry 23: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro EF, Lee R ( 2010): Cerebrospinal fluid 5‐hydroxyindolacetic acid and homovanillic acid: Reciprocal relationships with impulsive aggression in human subjects. J Neural Transmission 117: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JW ( 1989): The Criminal Elite, 2nd ed. New York: St. Martin's Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crider A ( 2008): Personality and electrodermal response lability: An interpretation. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 33: 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A ( 1994): Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: GP Putnam's Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Lamm C ( 2007): The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: How low‐level computational processes contribute to meta‐cognition. Neuroscientist 13: 580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrfuss J, Brass M, Neumann J, von Cramon DY ( 2005): Involvement of the inferior frontal junction in cognitive control: Meta‐analyses of switching and stroop studies. Hum Brain Mapp 25: 22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Raine A, Venables PH, Dawson ME, Mednick SA ( 2010): Association of poor childhood fear conditioning and adult crime. Am J Psychiatry 167: 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Raine A, Yaralian PS, Yang YL ( 2010): Increased Volume of the striatum in psychopathic individuals. Biol Psychiatry 67: 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goghari VM, MacDonald AW ( 2009): The neural basis of cognitive control: Response selection and inhibition. Brain Cogn 71: 72–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Chamberlain SR, Monti MM, Duncan J, Owen AM ( 2010): The role of the right inferior frontal gyrus: Inhibition and attentional control. Neuroimage 50: 1313–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Gabrieli JDE ( 2010): Shared and selective neural correlates of inhibition, facilitation, and shifting processes during executive control. Neuroimage 51: 421–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB ( 1975): Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Connecticut. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoboni M, Molnar‐Szakacs I, Gallese V, Buccino G, Mazziotta JC, Rizzolatti G ( 2005): Grasping the intentions of others with one's own mirror neuron system. Plos Biol 3: 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK ( 2000): Wisconsin Card Sorting Test ‐ 64 Card Version: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML ( 2005): The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 691–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET ( 2004): The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: Evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Prog Neurobiol 72: 341–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton L, Leeper‐Piquero NL ( 2007): Can general strain theory explain white‐collar crime? A preliminary investigation of the relationship between strain and select white‐collar offenses, J Criminal Justice 35: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Giampietro V, Surguladze S, Brammer MJ, David AS ( 2006): The role of ‘shared representations’ in social perception and empathy: An fMRI study. Neuroimage 29: 1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TMC, Chan SC, Raine A ( 2008): Strong limbic and weak frontal activation to aggressive stimuli in spouse abusers. Mol Psychiatry 13: 655–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie CH, Specht K, Marshall JC, Fink GR ( 2006): Using fMRI to decompose the neural processes underlying the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Neuroimage 2006; 30: 1038–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narr KL, Hageman N, Woods RP, Hamilton LS, Clark K, Phillips O, Shattuck DW, Asarnow RF, Toga AW, Nuechterlein KH ( 2009): Mean diffusivity: A biomarker for CSF‐related disease and genetic liability effects in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 171: 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo‐Vazquez JL, Leboran V, Acuna C ( 2009): A role for the ventral premotor cortex beyond performance monitoring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 18815–18819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R, Simpson S ( 1993): A rational choice theory of corporate crime In: Clarke RVG, Felson M, editors, Routine Activities and Rational Choice Theory. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; pp 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ ( 2008): Psychophysiological correlates of aggression and violence: An integrative review. Phil Trans Roy Soc B‐Biol Sci 363: 2543–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Wasserman GA, Miller L, Coplan JD, Bagiella E, Kovelenku P, Myers MM, Sloan RP ( 1998): Heart period variability and psychopathology in urban boys at risk for delinquency. Psychophysiology 35: 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Lencz T, Bihrle S, LaCasse L, Colletti P ( 2000): Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Yang Y, Narr K, Toga A ( 2011): Sex differences in orbitofrontal gray as a partial explanation for sex differences in antisocial personality. Mol Psychiatry 16: 227–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerbo AS, Freedman LW, Raine A, Dawson ME, Venables PH ( 1992): A major effect of recording site on measurement of electrodermal activity. Psychophysiology 29: 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel K, Weisburd D, editors ( 1992): White Collar Crime Reconsidered. Boston: Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seguin JR, Parent S, Tremblay RE, Zelazo PD ( 2009): Different neurocognitive functions regulating physical aggression and hyperactivity in early childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50: 679–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay‐Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Goldsher D, Aharon‐Peretz J ( 2005): Impaired “affective theory of mind” is associated with right ventromedial prefrontal damage. Cogn Behav Neurol 18: 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck DW, Mirza M, Adisetiyo V, Hojatkashani C, Salamon G, Narr KL, Poldrack RA, Bilder RM, Toga AW ( 2008): Construction of a 3D probabilistic atlas of human cortical structures. Neuroimage 39: 1064–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ ( 2008): Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry 165: 429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterzer P, Stadler C, Krebs A, Kleinschmidt A, Poustka F ( 2005): Abnormal neural responses to emotional visual stimuli in adolescents with conduct disorder. Biol Psychiatry 57: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujii T, Okada M, Watanabe S ( 2010): Effects of aging on hemispheric asymmetry in inferior frontal cortex activity during belief‐bias syllogistic reasoning: A near‐infrared spectroscopy study. Behav Brain Res 210: 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goozen SHM, Fairchild G, Snoek H, Harold GT ( 2007): The evidence for a neurobiological model of childhood antisocial behavior. Psychol Bull 133: 149–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables PH, Christie MJ ( 1980): Electrodermal activity In: Martin I, Venables PH, editors. Techniques in Psychophysiology. New York: Wiley; pp 3–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D ( 1981): Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale ‐ Revised. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd D, Waring E, Chayet EJ ( 2001): White Collar Crime and Criminal Careers. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S, Weisburd D, Bode N ( 1982): Sentencing the white collar offender: Rhetoric and reality. Am Sociol Rev 47: 641–659. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Brammer MJ, Skerrett D, Lagopolous J, Rennie C, Kozek K, Olivieri G, Peduto T, Gordon E ( 2000): The neural correlates of orienting: an integration of fMRI and skin conductance orienting. Neuroreport 11: 3011–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Felmingham K, Kemp AH, Rennie C, Brown KJ, Bryant RA, Gordon E ( 2007): Mapping frontal‐limbic correlates of orienting to change detection. Neuroreport 18: 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Raine A, Colletti P, Toga AW, Narr KL ( 2009): Abnormal temporal and prefrontal cortical gray matter thinning in psychopaths. Mol Psychiatry 14: 561–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Raine A ( 2009): Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res‐Neuroimaging 174: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]