Abstract

Plaque composition is a potentially important diagnostic feature for carotid artery stenting (CAS). The purpose of this investigation is to evaluate the reproducibility of manual border correction in intravascular ultrasound with virtual histology (VH IVUS) images. Three images each were obtained from 51 CAS datasets on which automatic border detection was corrected manually by two trained observers. Plaque was classified using the definitions from the CAPITAL (Carotid Artery Plaque Virtual Histology Evaluation) study, listed in order from least to most pathological: no plaque, pathological intimal thickening, fibroatheroma, fibrocalcific, calcified fibroatheroma, thin-cap fibroatheroma, and calcified thin-cap fibroatheroma. Inter-observer variability was quantified using both weighted and unweighted Kappa statistics. Bland-Altman analysis was used to compare the cross-sectional areas of the vessel and lumen. Agreement using necrotic core percentage as the criterion was evaluated using the unweighted Kappa statistic. Agreement between classifications of plaque type was evaluated using the weighted Kappa statistic. There was substantial agreement between the observers based on necrotic core percentage (κ = 0.63), while the agreement was moderate (κquadratic = 0.60) based on plaque classification. Due to the time-consuming nature of manual border detection, an improved automatic border detection algorithm is necessary for using VH IVUS as a diagnostic tool for assessing the suitability of patients with carotid artery occlusive disease for CAS.

Keywords: intravascular ultrasound, virtual histology, plaque, carotid artery stenting, reproducibility, inter-observer variability

INTRODUCTION

Carotid artery disease amenable to revascularization accounts for 5 to 12% of new strokes, of which there are approximately 1 million events each year [1]. American Heart Association guidelines recommend surgical intervention, i.e. carotid endarterectomy (CEA), for symptomatic patients having stenosis 50–99% and for asymptomatic patients with stenosis 60–99% [1]. Alternatively, high surgical risk patients with severe stenosis may be eligible for carotid artery stenting (CAS) protected with a distal protection filter (DPF), used to capture plaque particulate. Otherwise, medical management is recommended. However, 13.1% of patients in the medically managed arm of NASCET (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial) had a major stroke or death over two years [2], indicating that a measure other than carotid stenosis is necessary to determine whether a patient should undergo a surgical or endovascular procedure.

Plaque morphology and composition have been identified as potential diagnostic features for intervention eligibility. Previous studies suggested that rupture-prone plaques have a large lipid-rich core with a thin fibrous cap [3], while a stable plaque has a thick fibrous cap, low lipid concentration, and few macrophages. Ruptured plaque emboli could potentially occlude distal vascular beds, resulting in a neurological event. Due to the potential importance of plaque composition in patient outcome, invasive (i.e., optical coherence tomography) and noninvasive (i.e., magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI) imaging methods have been developed to determine plaque vulnerability. Currently there is no consensus regarding the best imaging modality for plaque detection [4]. Noninvasive imaging, such as MRI and computed tomography (CT), have better penetration and spatial resolution than VH IVUS [5]. However, CT has inferior sensitivity and specificity than VH IVUS with the added risk of radiation exposure [5]. In addition, artifacts introduced by motion must be suppressed in MRI [5]. VH IVUS, although risky due to the invasiveness of the procedure, overcomes these shortcomings of MRI and CT.

Originally developed for plaque assessment and adaptive remodeling of coronary arteries, intravascular ultrasound with virtual histology (VH IVUS; Volcano Corporation, San Diego, CA) has gained attention recently for diagnosis of patients with carotid artery disease. It has the ability to differentiate in a minimally invasive manner between plaque types based on the concept that different tissues reflect ultrasound at different frequencies and intensities. Plaque composition is particularly problematic with CAS due to catheter manipulation and stent deployment, which can potentially disrupt plaque. VH IVUS could assist in patient management, i.e., patients with significant necrosis or calcifications may be better suited for CEA instead of CAS.

The diagnostic accuracy of IVUS with VH is dependent upon correct vessel and lumen border detection. As described in previous studies, one limitation of IVUS is that the automatic border detection can lead to segmentation errors, altering the plaque burden and classification [6, 7]. The objective of this investigation is to determine the reproducibility of manual border detection between observers. To accomplish this goal, 51 lesions in 51 CAS patients were subjected to pre-procedure VH IVUS. Two trained observers edited the automatic border detection as necessary and the inter-observer variability was assessed using both the weighted and unweighted Kappa statistics and Bland-Altman analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject population and image data sets

Data from 51 CAS patients treated from December 2007 to September 2010 were collected following approval of a retrospective medical record review IRB protocol waiving HIPAA authorization by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) ethics committee. At UPMC – Shadyside, CAS patients are routinely screened with VH IVUS to quantify plaque composition after DPF deployment and prior to stent placement. All patients included in the study underwent CAS with the use of DPFs.

The CAS procedures were completed by BMW and MHW and followed a similar protocol: patients were treated with aspirin prior to the procedure and continued indefinitely. They received clopidogrel 24 hours before the procedure and for three to four months postprocedure. Patients received heparin to maintain a therapeutic activated partialthromboplastin time of 250 to 300 seconds. Access was gained via the femoral artery. The lesion was crossed with the DPF guidewire and expanded. VH was obtained by manually pulling the 20 MHz IVUS catheter initially placed distal to the plaque lesion with an approximate pullback rate of 1 mm/s. Following imaging, the stent was deployed, post-dilated, and the DPF collapsed and removed.

Two observers (NAL and GMS), both trained in interpretation of ultrasound images, edited the automatic border detection as necessary in three images per case at the minimum lumen diameter (MLD), one prior to the MLD, and one after the MLD. The IVUS images’ spatial resolution is approximately 150 µm axially and 250 µm circumferentially [8]. The IVUS images were gated at the patient’s R-wave of the ECG cycle. The VH IVUS software application (Volcano s5 version 2.2.3, Volcano Corporation, San Diego, CA) color-coded the observer-edited borders into four plaque components using a statistics-based classification system: red (necrotic lipid core), yellow-green (fibrofatty), dark green (fibrous), and white (dense calcium).

After the images were color-coded, the observers classified the plaque into six different morphologies (listed in order from least to most vulnerable):

pathological intimal thickening (PIT);

fibroatheroma (FA);

fibrocalcific (FCa);

calcified fibroatheroma (CaFa);

thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA); and

calcified thin-cap fibroatheroma (CaTCFA).

The classifications depend primarily on the amount and location of necrotic core and dense calcium plaque. The earliest and most benign stage of plaque development is PIT, resulting from smooth muscle proliferation and accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages in the intima without evidence of necrosis [6]. FA occurs when necrotic core appears, containing necrotic debris, extracellular lipid, and cholesterol crystals [6]. Calcifications developed within the necrotic core results in CaFa. If the necrosis is within 120 µm of the surface, it is considered to be TCFA; if calcifications are present in TCFA, then it is CaTCFA [6]. Over time, unstable plaques may progress to the point of stability, resulting in FCa [6]. The morphologies were based upon the definitions in the CAPITAL (Carotid Artery Plaque Virtual Histology Evaluation) study, summarized in Table 1 [7]. The CAPITAL study calculated the diagnostic accuracy of VH IVUS in CAS and CEA patients as compared with histology [7].

Table 1.

Plaque type descriptions used in the CAPITAL study [7].

| Plaque Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Pathological intimal thickening | Fibrofatty > 10% |

| Fibroatheroma | Confluent necrotic core > 10% |

| Fibrocalcific | Confluent dense calcium > 10%, necrotic core and fibrofatty each < 10% |

| Calcified fibroatheroma | Fibroatheroma with confluent dense calcium |

| Thin-cap fibroatheroma | Necrotic core > 10%, confluent NC against lumen |

| Calcified thin-cap fibroatheroma | Thin-cap fibroatheroma with confluent dense calcium |

Statistical analysis

The reproducibility of manual border detection was quantified by Bland-Altman analysis and the Kappa statistic, which measures the agreement between two observers beyond chance. A Kappa statistic measure of 0 indicates chance agreement while perfect agreement yields a value of 1. The unweighted Kappa statistic (κ) was calculated using Equation 1, where Po is the observed agreement and Pc is the agreement expected by chance [9]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In Equations 2 and 3, a is the number of times the observers agreed, d is the number of times the observers disagreed, n is the total number of borders, f1 is the total number of images classified by observer 2 as having necrotic core >10%, f2 is the total number of images classified by observer 2 as having necrotic core <10%, g1 is the total number of images classified by observer 1 as having necrotic core >10%, and g2 is the total number of images classified by observer 1 as having necrotic core <10%. The vessel and lumen cross-sectional areas were recorded for each image for each observer. Necrotic core percentage was selected as a basis for agreement due to the plaque definitions listed in Table 1 frequently using 10% necrotic core as a distinguishing characteristic. For each data set, it was recorded whether observer 1 or 2 edited the borders resulting in greater than or less than 10% necrotic core plaque.

Bland-Altman plots and histograms for the lumen area, vessel area, and necrotic core percentages were created. The mean difference between the observers and standard deviation of the differences was calculated for each data set. The bias and agreement was calculated using [10]. Statistical analyses were completed using MedCalc for Windows (version 10.2.0.0, MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

The weighted Kappa statistic was used as another method for assessing observer agreement. This methodology was based on plaque classification instead of cross-sectional area, which is potentially more clinically relevant. A 10% or 20% difference in cross-sectional area may not result in a different clinical diagnosis, while a difference in necrotic core plaque percentage does not indicate spatial location leading to a different diagnosis. An adapted Kappa was used based upon hierarchical categories [9]. The plaque types were categorized in order from the lowest to the highest potential for embolization: no plaque, PIT, FA, FCa, CaFa, TCFA, CaTCFA. The degree of disagreement was weighted to penalize more serious disagreements, e.g. the difference between PIT and TCFA is more severe than between PIT and FA. The weights were calculated using both linear and quadratic schemes, according to Equations 4 and 5:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where i − j is the number of categories of disagreement between the two observers and k is the number of categories. The weighted Kappa statistic is calculated using Equation 6:

| (6) |

where Σwfo is the sum of the weighted observed frequencies in the cells of the contingency table and Σwfc is the sum of the weighted frequencies expected by chance in the cells of the contingency table.

RESULTS

Nearly all (94%) of the 153 images (51 patients × 3 images/patient) in the study were altered by one or both of the observers after the automatic segmentation algorithm was executed. There were cases where only one of the observers altered the image. In this scenario, 88% of the images were altered, where the total number of images is double the sample number (two observers × 51 patients × 3 images/patient = 306 images for both observers).

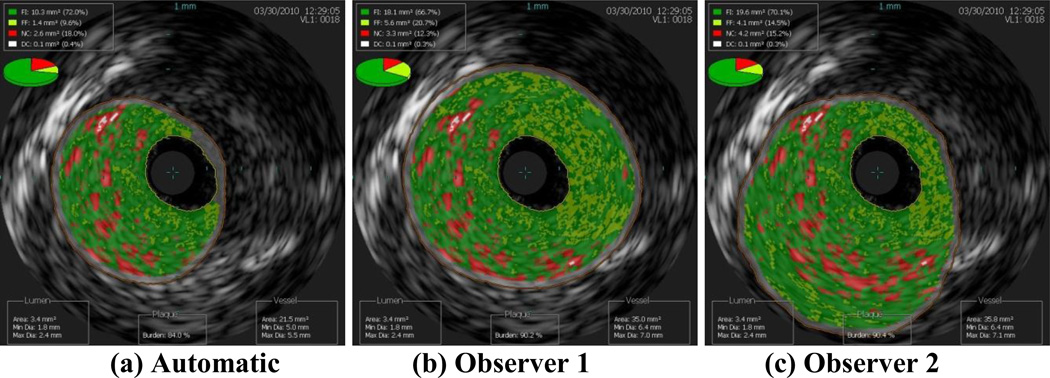

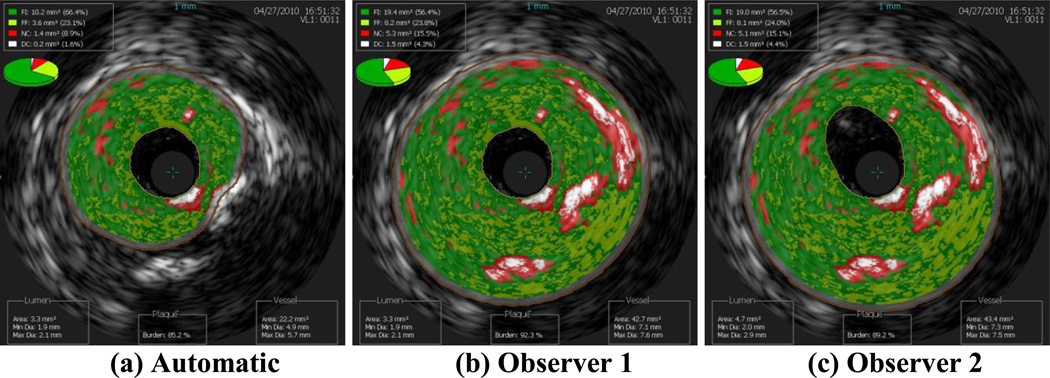

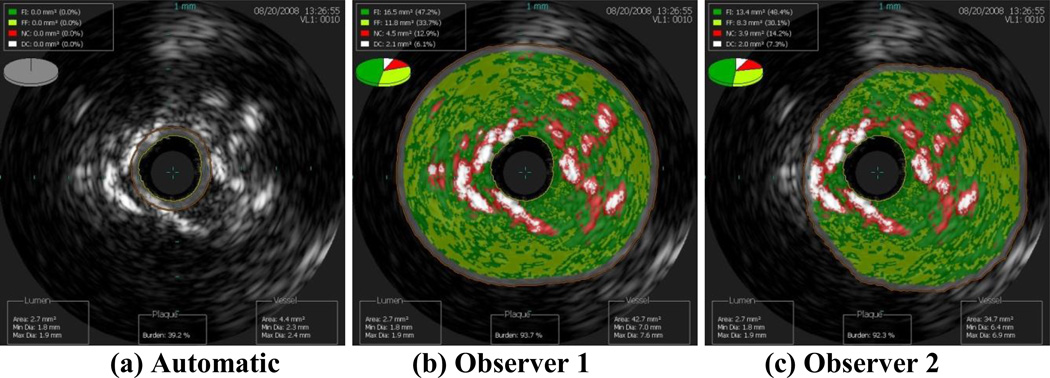

Images of the border detection from three data sets completed by both observers and by the automatic segmentation algorithm are presented in this work to demonstrate how altering the borders changes the plaque classification. Clearly, the best case scenario is when the two observers both agreed with the automatic segmentation, which occurred for nine of the 153 images included in this study (6%). The next best case scenario is when the automatic border detection is altered slightly, but not changing the plaque classification. In Figure 1, both observers altered the border segmentation, but all three images result in the plaque classification FA. The average scenario is moderate border alteration that changed the plaque classification slightly, such as from PIT to FA. In Figure 2, both observers altered the automatic border segmentation, changing the plaque classification from FA to CaFa. The worst case scenario is when altering the border changed the plaque classification drastically, such as FA to TCFA or CaTCFA. In Figure 3, the automatic border detection did not find any plaque, while both observers altered the borders and classified the plaque as CaTCFA. Since certain plaque types are more prone to rupture, proper border detection and plaque classification are very important for predicting patient outcome. Note that in the nine images illustrated in Figures 1–3, the lumen is nearly identical to each other for each data set. Thus, it is the vessel border that requires intervention by the observers.

Figure 1.

Best case scenario: slight alteration of the (a) automatic segmentation by observers (b) 1 and (c) 2, resulting in the same plaque classification (FA).

Figure 2.

Average case scenario: moderate alteration of the (a) automatic segmentation by observers (b) 1 and (c) 2, resulting in changing the plaque classification from FA (automatic) to CaFa (observers 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

Worst case scenario: drastic alteration of the (a) automatic segmentation by observers (b) 1 and (c) 2, resulting in changing the plaque classification from none (automatic) to CaTCFA (observers 1 and 2).

The baseline patient characteristics were collected from the 51 CAS procedures performed on 51 subjects. The average age was 73 years ± 9; 52.9% of the patients were male and approximately one third of the patients were symptomatic (37.3%, see Table 2). Both observers agreed that the majority of the patients had PIT, followed by CaFa then FA plaque types (see last column of Table 3 for observer 1 results and last row of Table 3 for observer 2 results). By examining the cells lying on the diagonal of Table 3, the observers agreed that 1 data set had no plaque, 45 data sets had PIT, 14 had FA, 17 had CaFa, and 15 had CaTCFA. The plaque types most likely to embolize, TCFA and CaTCFA, comprised approximately one-tenth of the images (19/153, 12%) determined by observer 1 and approximately one-fifth of images (32/153, 21%) as determined by observer 2. Of symptomatic patients, approximately two-fifths had PIT (observer 1: 25/57, 44%; observer 2: 22/57, 39%) and approximately one-fifth had CaTCFA (observer 1: 13/57, 23%; observer 2: 12/57, 21%; see Table 4).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of the retrospective record review used in this investigation.

| Characteristic | Number (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, average ± standard deviation (range) | 73 ± 9 (47 – 92) |

| Age > 80 years | 15 (29.4) |

| Male | 27 (52.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (35.3) |

| History of dyslipidemia | 37 (72.5) |

| History of hypertension | 41 (80.4) |

| Current smoking | 10 (19.6) |

| CAD * | 32 (62.7) |

| CKD † | 11 (21.6) |

| Angina | 5 (9.8) |

| Prior MI | 13 (25.5) |

| Prior PCI/PTCA ‡ | 10 (19.6) |

| Prior CEA | 11 (21.6) |

| Prior TIA or amaurosis fugax | 19 (37.3) |

| Stroke within 6 months of CAS | 7 (13.7) |

| Symptomatic | 19 (37.3) |

| CHF § | 8 (15.7) |

| Contralateral occlusion | 4 (7.8) |

| Restenosis after CEA | 8 (15.7) |

CAD = coronary artery disease

CKD = chronic kidney disease

PCI/PTCA = percutaneous coronary intervention/percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

CHF = congestive heart failure

Table 3.

Plaque classification agreement.

| Observer 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | PIT | FA | FCa | CaFa | TCFA | CaTCFA | Total | ||

| Observer 1 | None | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| PIT | 7 | 45 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 65 | |

| FA | 2 | 6 | 14 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 32 | |

| FCa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CaFa | 0 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 5 | 34 | |

| TCFA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CaTCFA | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 15 | 19 | |

| Total | 10 | 59 | 24 | 0 | 27 | 4 | 29 | 153 | |

Table 4.

Plaque types of symptomatic patients.

| Plaque Type | Observer 1 | Observer 2 |

|---|---|---|

| No plaque | 1 | 5 |

| Pathological intimal thickening | 25 | 22 |

| Fibroatheroma | 9 | 5 |

| Fibrocalcific | 0 | 0 |

| Calcified fibroatheroma | 13 | 12 |

| Thin-cap fibroatheroma | 0 | 1 |

| Calcified thin-cap fibroatheroma | 9 | 12 |

| Total images for 19 patients | 57 | 57 |

Of the 51 subjects included in this study, there was one transient ischemic attack (TIA), three strokes, and one death within 30 days of completion of CAS. The 30-day stroke and death rate was 7.8%. The five adverse events occurred one each in five individuals, all of whom had hypertension. All three subjects who experienced stroke also had high cholesterol. The three stroke patients all had at least one IVUS image classified as plaque type CaTCFA by one or both observers. The plaque classifications for the other two adverse event cases were more benign with worst plaque type FA (TIA) and CaFa (death).

Using 10% cross-sectional area difference between the observers as the agreement parameter, the observers agreed 92% (141/153) for the lumen and 78% (120/153) for the vessel border detection. For 20% cross-sectional area difference, the agreement for the lumen was 97% (148/153) and for the vessel 91% (139/153). Note that this agreement metric does not take into account the agreement expected by chance. The Kappa statistic was not used in this case since the observers were not classifying the data into categories, such as whether the plaque had more or less than 10% necrotic core. If chance agreement of 50% was assumed, then the Kappa statistics were “almost perfect” for the lumen (10%: 0.84, 20%: 0.93) [11]. Results were not as desirable for the vessel; “moderate” agreement for the 10% cross-sectional area difference criterion (0.57) and “almost perfect” for 20% criterion (0.82) [11]. As expected, the Kappa statistic indicated more agreement with a less stringent percentage difference requirement. The outcome of the unweighted Kappa statistic analysis based on necrotic core percentage is shown in Table 5. The unweighted Kappa statistic equaled 0.63, or “substantial” agreement [11].

Table 5.

Unweighted Kappa statistic using 10% necrotic core criterion.

| Observer 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 10% | < 10% | Total | ||

| Observer 1 | > 10% | 66 | 16 | 82 |

| < 10% | 12 | 59 | 71 | |

| Total | 78 | 75 | 153 | |

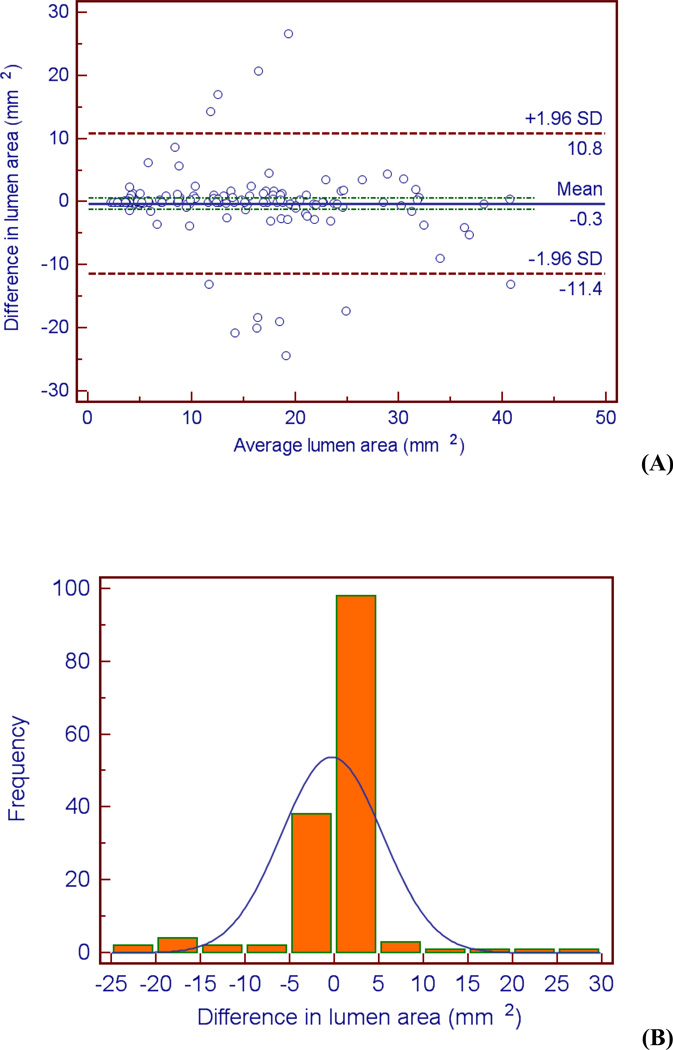

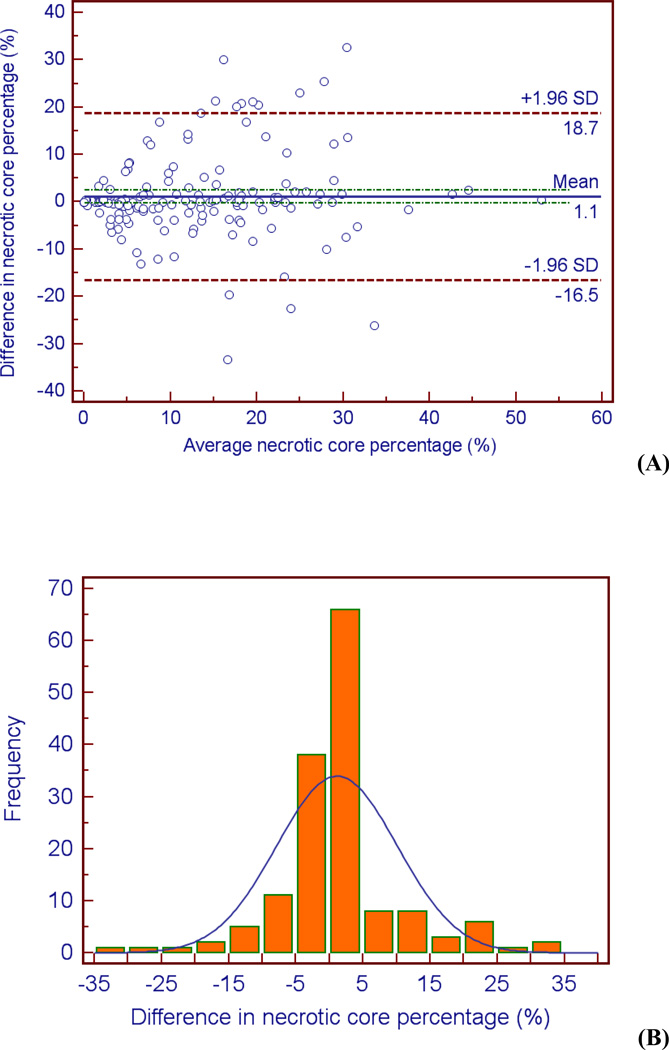

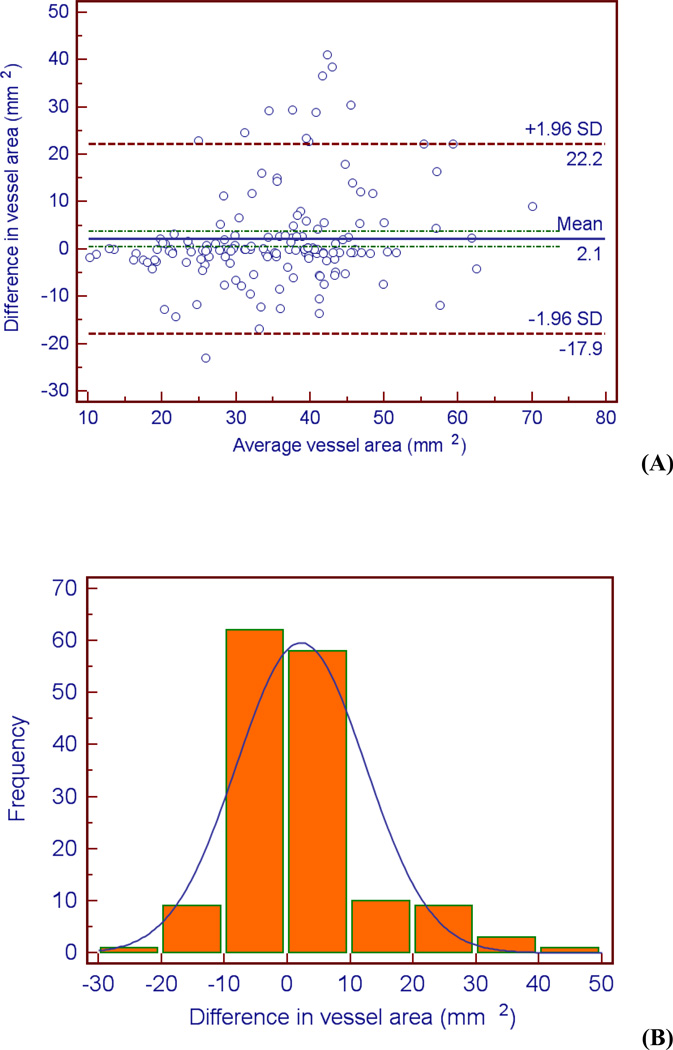

Examination of the Bland-Altman plots and histograms indicate that the majority of the data lies within two standard deviations of the mean and is approximately normally distributed for all three metrics (see Figures 4 – 6). It is evident from Figure 5b that there is greater variation in the difference in vessel area between the two observers. The bias of the data can be calculated by the mean difference d̄ and the standard deviation of the differences (s). The mean difference between the two observers d̄ was lowest for the lumen area, followed by necrotic core percentage, and vessel area (d̄lumen area = 0.30 mm2, d̄necrotic core = 1.09 mm2, d̄vessel area = 2.15 mm2). The same order was followed for the standard deviation of the differences s (slumen area = 5.67 mm2, snecrotic core = 8.98 mm2, svessel area = 10.2 mm2). These calculations indicate the level of agreement; there is more agreement between the observers when defining the lumen than the vessel (d̄lumen area = 0.30 mm2 versus d̄vessel area = 2.15 mm2).

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plot (A) and histogram (B) indicating differences (observer 1 – observer 2) between the observers when measuring lumen cross-sectional area.

Figure 6.

Bland-Altman plot (A) and histogram (B) indicating differences (observer 1 – observer 2) between the observers when measuring necrotic core percentage.

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman plot (A) and histogram (B) indicating differences (observer 1 – observer 2) between the observers when measuring vessel cross-sectional area.

The results of the inter-observer variability study based on plaque type are summarized in Table 3. The weighted Kappa statistic was calculated using both linear and quadratic weights using Equation 6. The Kappa statistics equaled κlinear = 0.54 and κquadratic = 0.60, both of which indicate “moderate” agreement [11]. The two observers agreed the most in the PIT classification (n = 45). Additionally, the first observer classified 6 data sets as PIT while the second observer classified them as FA. The difference between these plaque types is the amount of necrotic core plaque (PIT: < 10%, FA: > 10%).

DISCUSSION

Thus far, the use of VH IVUS during CAS has been explored on a small scale. The first use was described by Wilson et al. [12] in a study where both angiography and IVUS were used for quantitative assessment of luminal volume throughout the procedure. Other studies have compared angiography and IVUS for the selection of stent and balloon diameters [13]. Similarly, IVUS has been used to confirm the location of a guidewire, to decide between an endoluminal graft and a stent for treatment, to confirm adequate deployment of the graft or stent [14], to visualize stent malapposition [15], and to verify the distal ends of plaque stenosis during CEA [16]. Clark et al. [17] used IVUS to assess stent dimensions, expansion, and apposition as compared to angiography. The MLD of the distal ICA was similar regardless of imaging technique, but the IVUS-detected MLD after stent deployment was significantly smaller than for angiography (3.65 ± 0.68 mm versus 4.31 ± 0.76 mm, p < 0.001). Although angiography determined proper stent apposition, IVUS findings necessitated additional treatment for 9% of cases. Joan et al. [18] reported an overestimation of vessel size by IVUS as compared with angiography (1.64 ± 0.22 mm greater). IVUS was used to change stent sizes in 5 of the 18 patients treated and to change the treatment from CAS to CEA for patients with extreme concentric calcification or extensive necrosis. Hishikawa et al. [19] found a correlation between intraplaque hemorrhage and large necrotic core content and symptomatology.

The plaque composition assessed by IVUS has also been compared to the contents of DPF baskets post-CAS [14, 20]. In one case, repeated IVUS trials were conducted on the same patient during CAS [18]. IVUS indicated an intraluminal lesion near the distal end of the stent, which had characteristics consistent with ruptured plaque material (heterogeneous ultrasound pattern with hyperechoic and isoechoic regions). After 10 minutes, IVUS was repeated and the plaque lesion was absent. After retrieval of the DPF, it was shown that a large fragment of plaque material was contained in the basket. In a previous study, we hypothesized that plaque composition is related to CAS outcome. In this series of patients, Winston et al. [21] computed an association between peri-procedural TIA/stroke and FA (p = 0.0016). The results of this and the present study indicate that IVUS may be a useful tool for assessing carotid dimensions and plaque composition for CAS patients.

The objective of this investigation was to determine the reproducibility of manual border detection between observers. It is conjectured that if the reproducibility is reliable, then VH IVUS could be used as an adjunct to stenosis percentage for evaluating patient eligibility for CAS. The agreement between the observers using 10% cross-sectional area difference as the metric was 92% for the lumen and 78% for the vessel, not taking into account agreement due to chance. The Kappa statistic cannot be used in this comparison since it requires the observers to classify the data into categories; calculating the differences in area does not classify the data. The rationale behind comparing the cross-sectional areas is that if the observers agree on the borders, then the plaque components will be equally differentiated by the IVUS software, resulting in the same plaque classification. Following a similar rationale, necrotic core percentage was used as a criterion for agreement due to its dependence upon vessel and lumen borders; from trial to trial, the plaque type percentage will be the same if the borders are the same. There was substantial agreement between the observers on whether there was greater than or less than 10% necrotic core plaque. Agreeing on the 10% necrotic core plaque threshold eliminates certain plaque classifications, leading the observers to agree more often. For example, necrotic core plaque of greater than 10% eliminates PIT and FCa plaque. However, it should be noted that the cross-sectional area measure is not indicative of the spatial location of the borders. Thus, although cross-sectional areas may be similar between the observers, it may still result in different plaque classifications. The weighted Kappa statistic based on plaque classification indicated a moderate agreement between the observers.

There are three major limitations with the VH IVUS imaging modality: the use of a statistics-based classification system, the inability to resolve fibrous thin caps, and the inaccuracies of the automatic border detection algorithm. A statistics-based classification system is based on correlations between pixel intensity and histology results; thus, the method can lead to errors. The IVUS resolution is not high enough to resolve the thin fibrous cap that is typically seen in vulnerable plaques. IVUS resolution is approximately 150 µm axially and 250 µm circumferentially [8], while thin fibrous caps are typically less than 120 µm thick [22] and have been reported to be < 65 µm [23]. Due to the inability of IVUS to resolve the most rupture-prone plaque type, the VH IVUS “thin-cap fibroatheroma” definition may overestimate true thin-cap fibroatheroma, although CAPITAL showed good correlation between the two [6]. Thus, the clinical manifestation of the plaque type delineation based on the CAPITAL study is not always known. For example, two of the three patients who underwent stroke have similar looking plaque, but they are classified as two different plaque types (PIT and FA). This classification is based on the CAPITAL study criterion that FA plaques have greater than 10% necrotic core plaque. Finally, the automatic border detection algorithm was frequently incorrect, resulting in the need for user intervention.

To our knowledge, an inter-observer variability study has not been conducted on carotid VH IVUS images. Previous inter-observer variability studies have focused on the use of VH IVUS for imaging coronary arteries [24–26]. These studies support our findings that automatic border detection usually needs to be edited manually, resulting in mild but systematic differences [24, 25]. Manual border detection is time-consuming and subject to user bias. Rodriguez-Granillo et al. [26] found an inter-observer variability of 10% in plaque cross-sectional area measurements, which they cite as the commonly accepted threshold. Other previous inter- and intra-observer variability studies with VH IVUS have differed up to 20% [27], justifying the choice of the 10% and 20% metrics as a basis of comparison for the cross-sectional areas of the vessel and lumen borders.

CONCLUSIONS

The inter-observer variability study completed in this investigation indicates substantial agreement between two trained observers manually editing IVUS carotid vessel and lumen borders as quantified by the unweighted Kappa statistic based on necrotic core percentage. The threshold criteria of 10% and 20% cross-sectional area differences indicate that vessel border detection is more variable than lumen border detection. There was also moderate agreement based on plaque classification quantified by the weighted Kappa statistic. Although there is moderate to substantial agreement between observers, the algorithm for automatic border detection must be improved to be clinically relevant. Manual border detection is necessary in most cases and is time consuming. VH IVUS could be used in the future as an adjunct to stenosis percentage for determining patient eligibility for treatment, given the importance of evaluating the presence of vulnerable plaque types in carotid artery occlusive disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Biomechanics in Regenerative Medicine Training Program (T32 EB003391-01), a John and Claire Bertucci Fellowship, and Carnegie Mellon University’s Biomedical Engineering Department. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Gail M. Siewiorek is consultant to W.L. Gore and Associates. Natasha A. Loghmanpour and Brion M. Winston have no financial interests to disclose. Mark H. Wholey has disclosed that he is a consultant to Cordis, Abbott (Guidant), Medrad, Boston Scientific, Edwards LifeSciences, and Mallinckrodt. He is also co-founder and Chairman of the Board of Directors for NeuroInterventions, Inc. Ender A. Finol is co-founder and VP of Engineering for NeuroInterventions, Inc., and consultant to W.L. Gore and Associates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bates ER, Babb JD, Casey DE, Jr, Cates CU, Duckwiler GR, Feldman TE, et al. ACCF/SCAI/SVMB/SIR/ASITN 2007 clinical expert consensus document on carotid stenting: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents (ACCF/SCAI/SVMB/SIR/ASITN Clinical Expert Consensus Document Committee on Carotid Stenting) Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007 Jan 2;49(1):126–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborators NASCET. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1991 Jun;22(6):711–720. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golledge J, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. The symptomatic carotid plaque. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2000 Mar;31(3):774–781. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winston B, Wholey M. Which imaging modality is best for predicting stroke during carotid artery stenting? The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2011 Jun;52(3):299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matter CM, Stuber M, Nahrendorf M. Imaging of the unstable plaque: how far have we got? European heart journal. 2009 Nov;30(21):2566–2574. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiro BJ, Wholey MH. The expanding indications for virtual histology intravascular ultrasound for plaque analysis prior to carotid stenting. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2008 Dec;49(6):729–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diethrich EB, Pauliina Margolis M, Reid DB, Burke A, Ramaiah V, Rodriguez-Lopez JA, et al. Virtual histology intravascular ultrasound assessment of carotid artery disease: the Carotid Artery Plaque Virtual Histology Evaluation (CAPITAL) study. J Endovasc Ther. 2007 Oct;14(5):676–686. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair A. Personal communication [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Physical therapy. 2005 Mar;85(3):257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGinn T, Wyer PC, Newman TB, Keitz S, Leipzig R, For GG. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic) Cmaj. 2004 Nov 23;171(11):1369–1373. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson EP, White RA, Kopchok GE. Utility of intravascular ultrasound in carotid stenting. J Endovasc Surg. 1996 Feb;3(1):63–68. doi: 10.1583/1074-6218(1996)003<0063:UOIUIC>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandyk DF, Armstrong PA. Use of intravascular ultrasound as a "Quality Control" technique during carotid stent-angioplasty: are there risks to its use? The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2009 Dec;50(6):727–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irshad K, Millar S, Velu R, Reid AW, Diethrich EB, Reid DB. Virtual histology intravascular ultrasound in carotid interventions. J Endovasc Ther. 2007 Apr;14(2):198–207. doi: 10.1177/152660280701400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tresukosol D, Wongpraparut N, Lirdvilai T. The value of intravascular ultrasound-facilitated internal carotid artery stenting in a patient with heavily calcified and ambiguous common carotid artery stenosis. The Journal of invasive cardiology. 2007 Jul;19(7):E203–E206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamata T, Okada Y, Kondo S, Kawashima A, Tsutsumi Y, Hori T. Extravascular application of an intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) catheter during carotid endarterectomy to verify distal ends of stenotic lesions. Acta neurochirurgica. 2004 Nov;146(11):1205–1209. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark DJ, Lessio S, O'Donoghue M, Schainfeld R, Rosenfield K. Safety and utility of intravascular ultrasound-guided carotid artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004 Nov;63(3):355–362. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joan MM, Moya BG, Agusti FP, Vidal RG, Arjona YA, Alija MP et al. Utility of intravascular ultrasound examination during carotid stenting. Annals of vascular surgery. 2009 Sep-Oct;23(5):606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hishikawa T, Iihara K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Nagatsuka K, Yamada N, Miyamoto S. Virtual histology-intravascular ultrasound in assessment of carotid plaques: ex vivo study. Neurosurgery. 2009 Jul;65(1):146–152. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000346271.31050.AF. discussion 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wehman JC, Holmes DR, Jr, Ecker RD, Sauvageau E, Fahrbach J, Hanel RA, et al. Intravascular ultrasound identification of intraluminal embolic plaque material during carotid angioplasty with stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006 Dec;68(6):853–857. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winston BM, Siewiorek GM, Finol EA, Wholey MH. A case series of virtual histology intravascular ultrasound in carotid artery stenting. Vascular Disease Management. 2011 Aug;8(8):E144–E150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladich ER, Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP. Carotid atherosclerotic disease: Pathologic basis for treatment. London: Taylor & Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2000 May;20(5):1262–1275. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmann M, Mattern ES, Huisman J, van Houwelingen GK, de Man FH, Stoel MG, et al. Reproducibility of volumetric intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency-based analysis of coronary plaque composition in vivo. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2009 Jan;25(1):13–23. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9338-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huisman J, Egede R, Rdzanek A, Boese D, Erbel R, Kochman J, et al. Between-Centre Reproducibility of Volumetric Intravascular Ultrasound Radiofrequency-Based Analyses in Mild-to-Moderate Coronary Atherosclerosis: An International Multicentre Study. EuroIntervention. 2010;5:925–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Granillo GA, Vaina S, Garcia-Garcia HM, Valgimigli M, Duckers E, van Geuns RJ, et al. Reproducibility of intravascular ultrasound radiofrequency data analysis: implications for the design of longitudinal studies. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2006 Oct;22(5):621–631. doi: 10.1007/s10554-006-9080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier DS, Cothren RM, Vince DG, Cornhill JF. Automated morphometry of coronary arteries with digital image analysis of intravascular ultrasound. American heart journal. 1997 Jun;133(6):681–690. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]