Abstract

Objective

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is an acute-phase reactant that is increased in inflammatory diseases and in acute coronary syndromes. Cp has recently been shown to possess nitric oxide (NO) oxidase catalytic activity, but its impact on long-term cardiovascular outcomes in stable cardiac patients has not been explored.

Methods and Results

We examined serum Cp levels and their relationship with incident major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE = death, myocardial infarction [MI], stroke) over 3-year follow-up in 4,177 patients undergoing elective coronary angiography. We also carried out a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify the genetic determinants of serum Cp levels and evaluate their relationship to prevalent and incident cardiovascular risk. In our cohort (age 63±11 years, 66% male, 32% history of MI, 31% diabetes mellitus), mean Cp level was 24±6 mg/dL. Serum Cp level was associated with greater risk of MI at 3 years (Hazard ratio [HR, Quartile 4 versus 1] 2.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.79–3.09, p<0.001). After adjusting for traditional risk factors, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and creatinine clearance, Cp remained independently predictive of MACE (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.10–2.17, p=0.012). A two-stage GWAS identified a locus on chromosome 3 over the CP gene that was significantly associated with Cp levels (lead SNP rs13072552; p=1.90 × 10−11). However, this variant, which leads to modestly increased serum Cp levels (~1.5–2 mg/dL per minor allele copy), was not associated with coronary artery disease or future risk of MACE.

Conclusion

In stable cardiac patients, serum Cp provides independent risk prediction of long-term adverse cardiac events. Genetic variants at the CP locus that modestly affect serum Cp levels are not associated with prevalent or incident risk of coronary artery disease in this study population.

INTRODUCTION

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a circulating ferroxidase enzyme able to oxidize ferrous ions to less toxic ferric forms1. It is the major carrier of circulating copper and is synthesized and secreted by the liver. Ceruloplasmin acts not only as a mediator ofiron oxidation, but also is an acute phase reactant in the setting of inflammation (such as infections or inflammatory arthritis). In contrast, inherited liver disorders such as Wilson’s disease may present with lower than normal levels of circulating Cp.

Recent studies support a role of Cp in regulating nitric oxide (NO) homeostasis2. Isolated Cp was shown capable of catalytically consuming NO through NO oxidase activity, and plasma NO oxidase activity was decreased after ceruloplasmin immunodepletion, in ceruloplasmin knockout mice and in people with congenital aceruloplasminemia2. A mechanistic role for Cp in vascular disease beyond its association as an acute phase protein is thus suggested. Interestingly, myocardial uptake of Cp has been demonstrated in animal models3, and epidemiological studies have linked Cp levels with cardiovascular risk in both apparently healthy individuals4–7, and in the setting of acute coronary syndromes8–10. Despite the relative ease and affordability of Cp testing, few studies have examined Cp and its association with cardiovascular outcomes. The clinical prognostic value of Cp levels is not well understood, particularly in the contemporary era with statin therapy.

METHODS

Study population

The Cleveland Clinic GeneBank study is a large, prospective cohort study from 2001–6 that established a well-characterized clinical repository with clinical and longitudinal outcomes data composed of consenting subjects undergoing elective diagnostic cardiac catheterization procedure. All GeneBank participants gave written informed consent approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. This analysis included 4,177 consecutive subjects of white European ancestry without evidence of myocardial infarction (MI: cardiac troponin I <0.03 ng/mL) with plasma samples available for analysis. An estimate of creatinine clearance (CrCl) was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation. The presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) was confirmed by luminal stenosis of at least 50% in any major coronary arteries. Major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) was defined as death, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal cerebrovascular accident following enrollment. Adjudicated outcomes were ascertained over the ensuing 3 years for all subjects following enrollment.

Ceruloplasmin Assay

Quantitative determination of Cp was performed using an immunoturbidimetric assay (Abbott Architect ci8200, Abbott Park IL), which provides highly sensitive measurement of ceruloplasmin levels with an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.7% and inter-assay precision of up to 4%, and a reference range of 20–60 mg/dL. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), myeloperoxidase (MPO), uric acid, creatinine, and fasting blood glucose and lipid profiles were measured on the same platform as previously described11.

Genotyping

Genome-wide genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was performed on the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human Array 6.0 chip in a subset of European ancestry patients in GeneBank. Using these data and those from 120 phased chromosomes from the HapMap CEU samples (HapMap r22 release, NCBI build 36), genotypes were imputed for untyped SNPs across the genome using MACH 1.0 software. All imputations were done on the forward (+) strand using 562,554 genotyped SNPs that had passed quality control (QC) filters. QC filters for the imputed dataset excluded SNPs with HWE p-values < 0.0001 or minor allele frequencies < 1%, and individuals with less than 95% call rates. This resulted in 2,421,770 autosomal SNPs that were available for analysis.

Statistical Analyses

The Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon-Rank sum test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables were used to examine the difference between the groups. Kaplan–Meier analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression was used for time-to-event analysis to determine Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for 1-year and 3-year MACE. Levels of Cp were then adjusted for traditional cardiac risk factors in a multivariable model including age, gender, diabetes mellitus, systolic blood pressure, low-and high-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, as well as log-transformed hsCRP, and CrCl. ROC curve analyses and 5-fold cross validation were used to determine the optimal cutoff. The improvement in model performance introduced by the inclusion of Cp was evaluated using net reclassification improvement (NRI) index. C statistic was calculated using the area under ROC curve (AUC). To determine the optimal cutoff for Cp, we used a logistic regression model to estimate the risk of MACE. The five-fold cross validation divides the data into five approximately equally-sized portions, and a logistic regression model is trained on four parts of the data and then estimates the risk of MACE in the fifth part. This is repeated for each of the five parts, and the AUC with the estimated risk was calculated. This process is carried out for a grid of values of Cp cutoff values, ranging from 17.3 mg/dL (10th percentile) to 31.5 mg/dL (90th percentile) with an increment of 0.1 mg/dL. The optimal cutoff is chosen to maximize AUC values. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A GWAS for serum Cp levels was carried out with adjustment for age and gender under an additive model. Linear regression analyses were carried out with PLINK (v1.07) using log transformed values. Unconditional multiple logistic regression was used to independently test for association of genetic variants with the presence and severity of CAD, with adjustment for age, gender, medication use (aspirin and/or statins), and Framingham ATP-III risk score (which includes smoking and diabetes status). Relative risk for experiencing a MACE was assessed using Cox proportional hazard models with adjustment for age, gender, medication use, and Framingham ATP-III risk score. These analyses were carried out assuming additive and dominant models. Adjusted odds or hazard ratios (OR or HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported with 2-sided p-values. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 9.2 (Vienna, Austria) and SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean and median serum Cp levels were 24 mg/dL and 23 mg/dL (interquartile range 20–27 mg/dL), respectively. Patients with elevated Cp were more likely to be older, female gender, with more cardiovascular risk factors including dyslipidemia, history of diabetes mellitus, and poorer renal function at baseline. There was strong direct correlation between Cp and hsCRP (r=0.52, p<0.001), but far weaker correlations with total leukocyte count (r=0.15, p<0.001) or myeloperoxidase (MPO, r=0.12, p<0.001), and no correlation with serum uric acid levels (r=0.02, p=0.09).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Without Event | With Event | |

|---|---|---|

|

Demographics and Cardiovascular Risk Factors

| ||

| Age (years) | 63±11 | 67±10 |

| Male (%) | 67 | 64 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 29 | 41 |

| Hypertension (%) | 70 | 75 |

| Smokers (Former/Current, %) | 65 | 70 |

| Prior myocardial infarction (%) | 31 | 44 |

|

| ||

|

Laboratory Data

| ||

| LDL cholesterol [mg/dL] | 95 (77–116) | 95 (77–116) |

| HDL cholesterol [mg/dL] | 34 (28–41) | 33 (27–40) |

| Triglycerides [mg/dL] | 114 (83–162) | 120 (84–163) |

| Total leukocyte count [WBCP/hpf] | 6.04 (5.02–7.34) | 6.21 (5.07–7.53) |

| Uric acid [mg/dL] | 6.1 (5.1–7.2) | 6.5 (5.5–7.8) |

| hsCRP [mg/L] | 1.95 (0.90–4.36) | 3.50 (1.46–7.22) |

| Myeloperoxidase [pg/mL] | 102 (70–189) | 115 (74–227) |

| Creatinine clearance [ml/min/1.73m2] | 102 (79–127) | 86 (59–114) |

|

| ||

|

Baseline Medications

| ||

| Aspirin (%) | 74 | 67 |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers (%) | 61 | 63 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (%) | 48 | 58 |

| Statin therapy (%) | 60 | 55 |

Events defined as death, myocardial infarction, or stroke. Values expressed in median (interquartile ranges)

Association of Serum Cp Levels with Future MACE

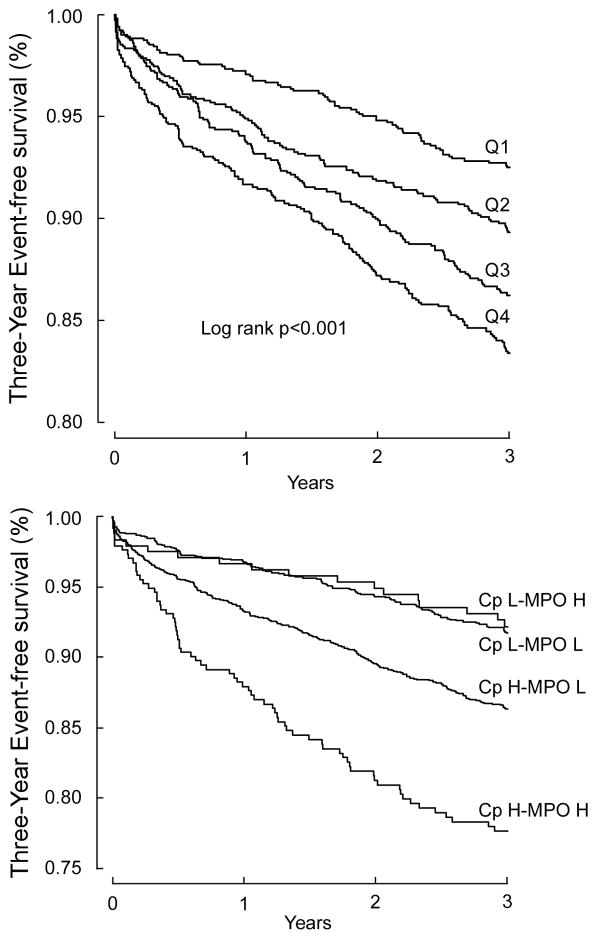

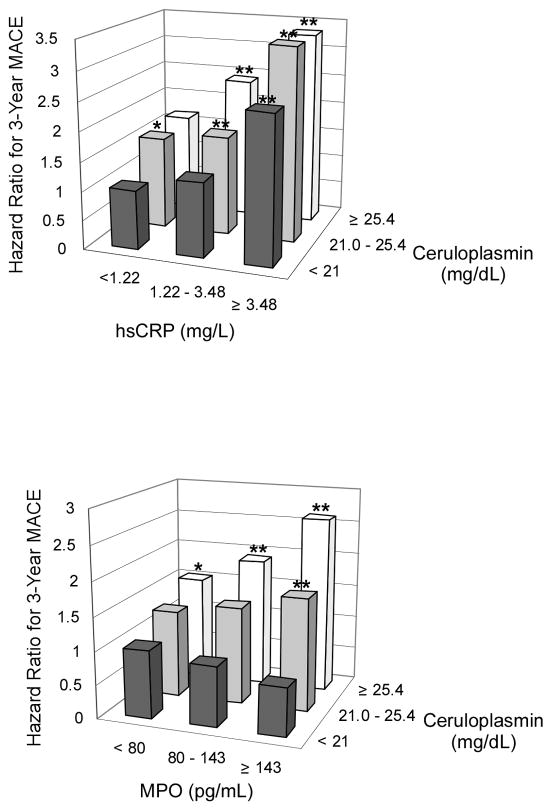

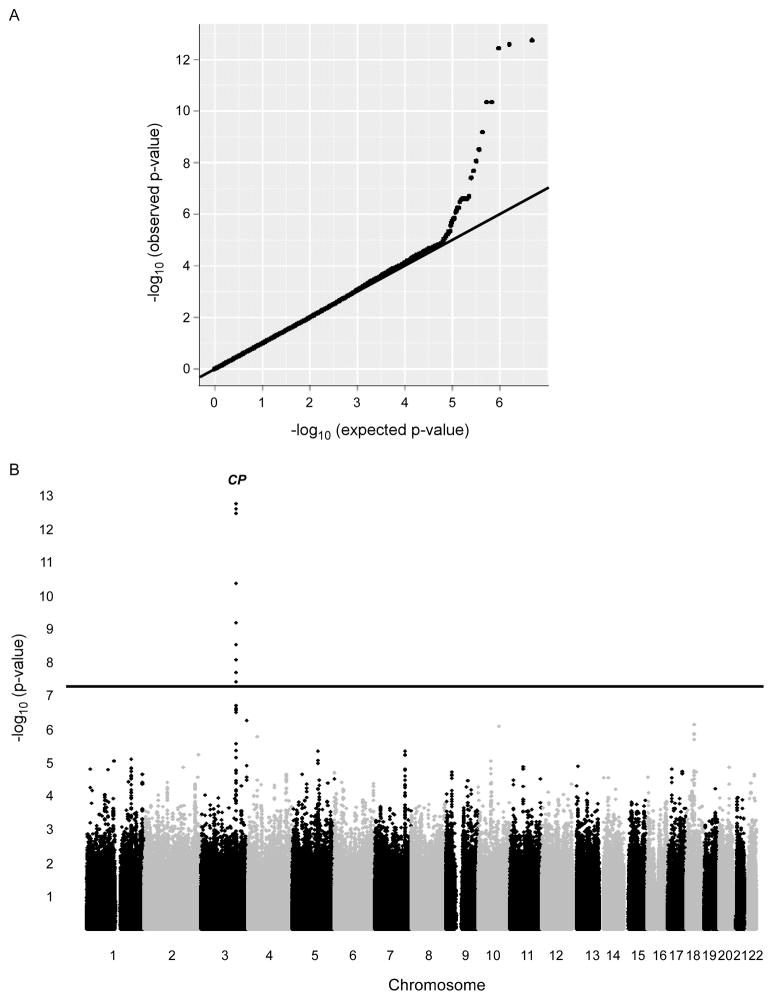

Table 2 demonstrated the relationship between Cp levels in quartiles with 3-year risk for incident MACE. This graded risk was clearly illustrated in the Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 1a) when stratified according to quartile Cp ranges (e.g. Quartiles 1 versus 4, Hazard ratio: 2.35, 95%CI 1.79–3.09, p<0.001). After adjusting for traditional risk factors, increased Cp levels remained significantly associated with incident major long-term major adverse cardiac events at 3 years (Table 2). The results were similar when stratified by gender, even though the cut-offs of the quartiles were higher in women (adjusted HR 1.77, 95%CI 1.13–2.77, p=0.013; 4th quartile Cp >31.5 mg/dL) than in men (adjusted HR 2.55, 95% CI 1.82–3.57, p<0.001; 4th quartile Cp >24.6 mg/dL). In particular, those with elevated Cp (cut-off at 22 mg/dL) and MPO (cut-off at 322 pg/mL), another known oxidase that contributes to catalytic consumption of NO within the vascular compartment12–14, experienced the highest risk of developing future MACE (Figure 1b). Such prognostic value remained significant in various subgroups stratified by age, gender, presence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or renal insufficiency (Figure 2). When stratified by hsCRP or with MPO, we observed synergistic prediction of future MACE (Figure 3, Table 2). Inclusion of Cp resulted in a significant improvement in risk estimation, based on NRI index (9.6%, p<0.001) and C statistic (67.7% versus 65.2%, p=0.003).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratio for major adverse cardiac events at 3-year follow-up according to serum ceruloplasmin quartiles

| Serum Ceruloplasmin Level

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

| All Subjects (n=4,177) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Range (mg/dL) | <19.9 | 19.9–23.1 | 23.1–27.0 | ≥27.0 |

|

| ||||

| Event rate | 74/1044 | 106/1044 | 133/1042 | 169/1047 |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | 1 | 1.46 (1.09–1.97)* | 1.91 (1.44–2.53)** | 2.35 (1.79–3.09)** |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.38 (1.02–1.87)* | 1.66 (1.24–2.22)** | 2.22 (1.64–3.00)** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.40 (1.03–1.91)* | 1.82 (1.35–2.45)** | 2.47 (1.81–3.39)** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.25 (0.93–1.69) | 1.39(1.03–1.88)* | 1.50 (1.06–2.13)* |

|

| ||||

| Secondary Prevention Subjects (n=3,100) | ||||

| Event rate | 60/772 | 93/774 | 109/779 | 143/775 |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | 1 | 1.59 (1.16–2.2)** | 1.84 (1.35–2.52)** | 2.48 (1.84–3.35)** |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.45 (1.04–2.02)* | 1.54 (1.11–2.14)** | 2.08 (1.48–2.91)** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.49 (1.06–2.08)* | 1.67 (1.19–2.34)** | 2.42 (1.70–3.43)** |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1.34 (0.97–1.86) | 1.33 (0.95–1.87) | 1.54(1.05–2.25)* |

|

| ||||

| Primary Prevention Subjects (n=1,077) | ||||

| Event rate | 12/269 | 14/269 | 23/268 | 18/271 |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | 1 | 1.17 (0.55–2.53) | 2.00 (1.00–4.00) | 2.41 (1.23–4.72)* |

| Adjusted | 1 | 1.35 (0.62–2.93) | 2.42 (1.20–4.87)* | 3.19 (1.54–6.62)** |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.40 (0.64–3.05) | 2.51 (1.24–5.09)* | 3.54 (1.71–7.35)** |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.14 (0.52–2.52) | 1.77 (0.87–3.62) | 1.74 (0.76–4.00) |

| Model 3 | ||||

p<0.01 and

p<0.05 (comparing with 1st quartile);

HR = Hazard ratio, MACE = major adverse cardiac events (death, MI, stroke).

Model 1: adjusted for traditional risk factors (including age, gender, systolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking, diabetes mellitus) and medications (ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, statin, aspirin)

Model 2: adjusted for traditional risk factors plus myeloperoxidase.

Model 3: adjusted for traditional risk factors plus hsCRP and serum uric acid.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for 3-year major adverse cardiac events stratified according to serum ceruloplasmin quartiles (A); and for groups stratified by high/low serum ceruloplasmin (<22 mg/dL vs ≥22 mg/dL) and high/low plasma myeloperoxidase levels (<322 pg/mL vs ≥322 pg/mL) (B). Abbreviations: Cp, ceruloplasmin; Q, quartile; H, high; L, low; MPO, myeloperoxidase.

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of risk prediction for serum ceruloplasmin levels according to subgroups. Abbreviations: HTN, hypertension; CAD, coronary artery disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell; MPO, myeloperoxidase

Figure 3.

Event rates for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) stratified according to tertiles of ceruloplasmin (Cp) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP, top) and myeloperoxidase (MPO, bottom)

GWAS for Serum Cp Levels

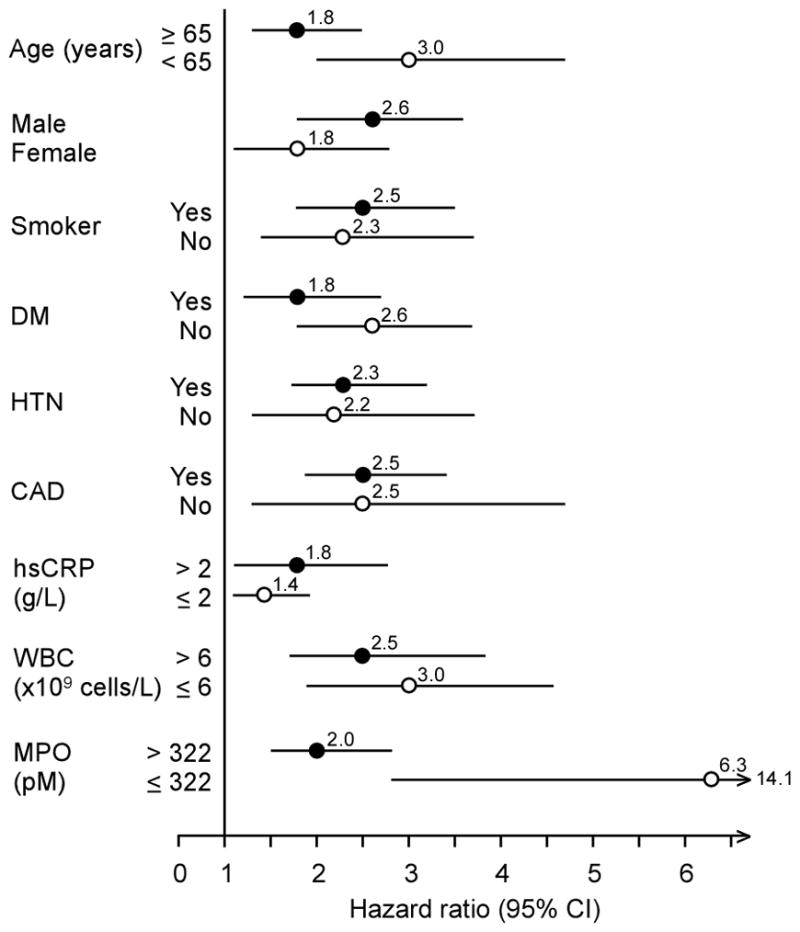

We next performed a two-stage GWAS for serum Cp levels in 4,697 GeneBank subjects (all of European ancestry). In stage 1 (n=2647), the genomic inflation factor was 1.001, indicating that the GWAS results are not affected by underlying population (Figures 4). Serum Cp levels were primarily controlled by a single locus on chromosome 3, which contains the CP gene itself. As shown in Table 3, the lead SNP at this locus (rs13072552) modestly but significantly increases of serum Cp levels by 2–3 mg/dL as a function of carrying 1 or 2 copies of the T allele (p=3.63 × 10−13). The rs13072552 SNP has a minor allele frequency of 0.08, is located in intron 9 of CP, and is in strong linkage disequilibrium (r2>0.7) with the two other SNPs at this locus (rs11714000 and rs11921705) that exhibit similar association with Cp levels (data not shown). In stage 2, we genotyped 2,050 additional GeneBank subjects in whom Cp levels were available and confirmed the association of rs13072552 (p=2.42 × 10−02). This association remained highly significant in a combined analysis with all 4,697 subjects (Table 3), and an analysis stratified by gender did not suggest that the association was sex-specific (Supplemental Materials, Table I).

Figure 4.

Q-Q and Manhattan plots from GWAS for serum ceruloplasmin levels. The p-values obtained from SNPs in the GWAS analyses deviate from that expected by chance, suggesting that a subset of these signals indicate true associations (A). Serum ceruloplasmin levels in this study population (n = 2,647) are controlled predominantly by locus on chromosome 3 containing the CP gene (B).

Table 3.

Association of rs13072552 with Serum Cp Levels.

| Stage | MAF | GG | GT | TT | * p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS (n = 2,647) | 0.081 | 23 ± 6 (n = 2234) | 25 ± 6 (n = 393) | 28 ± 8 (n = 20) | 3.63 × 10−13 |

| Replication (n = 2,050) | 0.077 | 25 ± 6 (n = 1774) | 26 ± 6 (n = 263) | 24 ± 9 (n = 13) | 2.42 × 10−02 |

| Combined (n = 4,697) | 0.079 | 24 ± 6 (n = 4008) | 25 ± 6 (n = 656) | 26 ± 9 (n = 33) | 1.90 × 10−11 |

Mean serum Cp levels as a function of genotype for rs13072552. Minor allele frequency (MAF).

p-values obtained using log transformed Cp values and after adjustment for age and gender.

Association of CP Variants with Prevalent and Incident Risk of CAD

We next sought to determine whether the genetic factors controlling Cp levels were associated with prevalent and incident risk of CAD. In addition to the 4,697 subjects used for the quantitative analyses described above, we genotyped rs13072552 in 3,448 additional GeneBank subjects with available CAD phenotype data for these analyses (total n=8,145). Under an additive model, the T allele of rs13072552, which increases serum Cp levels, was not associated with the presence or severity of CAD (Table 4). We also did not observe an association with history of MI in subjects with CAD or with future risk of MACE (Table 4) or when males and females were analyzed separately for MACE (p=0.39 for males; p=0.51 for females). Given the small number of subjects and to increase power, we also carried out these analyses using a dominant model with TT homozygotes grouped together with GT heterozygotes. However, these analyses also did not reveal an association with CAD, history of MI, or MACE (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association of rs13072552 with Prevalent and Incident Risk of CAD.

| Trait | GG (n = 6941) | GT (n = 1130) | TT (n = 74) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CAD vs. CAD+ (OR, 95% CI) | 1 | 0.99 (0.84 – 1.17) | 1.44 (0.72 – 2.87) | 0.74 |

| a No Disease vs. Mild Disease (OR, 95% CI) | 1 | 0.92 (0.78 – 1.09) | 1.21 (0.67 – 2.19) | 0.61 |

| a No Disease vs. Severe Disease (OR, 95% CI) | 1 | 1.04 (0.87 – 1.24) | 0.69 (0.35 – 1.39) | 0.93 |

| CAD+/MI− vs. CAD+/MI+ (OR, 95% CI) | 1 | 0.97 (0.83 – 1.13) | 1.02 (0.60 – 1.74) | 0.77 |

| Future MACE (HR, 95% CI) | 1 | 1.08 (0.91 – 1.28) | 1.32 (0.78 – 2.23) | 0.22 |

Odds and Hazard ratios were calculated with adjustment for age, gender, medication use (aspirin and/or statins), and Framingham risk score.

Disease severity was defined as having ≥50% stenosis in 1 or 2 (Mild) or ≥3 (Severe) major epicardial arteries.

DISCUSSION

A key finding of this study is the strong independent prognostic value of circulating Cp levels in stable patients undergoing cardiac evaluation in the contemporary statin era, above and beyond traditional cardiac risk factors as well as cardiac and inflammatory risk markers. However, the effect of underlying genetic determinants of serum Cp levels were modest, and there was no gender-specific difference in prognostic value despite higher serum levels of Cp observed in women versus in men. With the broad availability and economic testing for serum Cp measurements in the clinical setting, these findings highlight the need to gain further insights into underlying pathophysiologic process related to increased serum Cp levels, which can impact long-term outcomes.

The precise role Cp plays in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been well-described, although there has been extensive literature dating back to the 1970s describing the association between Cp and the heart3, 15, as well as its important oxidase activities16. Patients with MI have observed higher serum Cp levels, which returned to normal ranges over time, suggesting its restrictive role as an acute phase reactant17. Nevertheless, recent mechanistic studies show Cp functions as an NO oxidase in vivo, suggesting Cp elevations may lead to decreased NO bioavailability and endovascular dysfunction2. Our findings are consistent with findings from prior epidemiologic data in patients without known CAD. In the Helsinki Heart Study of dyslipidemic, middle-age men, higher serum Cp level (but not ferritin) was associated with graded increase in risk of cardiovascular events in a case-control comparison18. Another prospective cohort study of elderly subjects also demonstrated a relationship between serum Cp levels and subsequent development of MI, while adjustment for hsCRP and leukocyte count reduced the excess risk by 33%5. Unlike our present study population, the majority of patients in prior reports did not have prevalent cardiac diseases and were not treated with cardiac or lipid-lowering medications. It is interesting to observe that in our patient population with contemporary cardiac care, we still observed strong correlations between Cp and hsCRP levels but far weaker associations with MPO and leukocyte counts.

Cytokines released from jeopardized tissues may stimulate the liver to synthesize acute phase proteins. Ceruloplasmin is one of these well-known inflammation-sensitive plasma proteins, found to have protective effects in isolated rat hearts subjected to ischemia–reperfusion19, 20. The exact mechanisms for the cardioprotection are unclear, but likely are due to a wide variety of extracellular anti-oxidative ferroxidase and ROS scavenging effects1, combined with putative glutathione (GSH)-peroxidase and NO-oxidase/S-nitrosating activities21. Whether such potentially beneficial effects are modified by oxidative stress22, 23 and progress into vasculopathic factors that promote disease progression has been debated24.

In the present study, we also used a GWAS approach to investigate the genetic determinants of serum Cp levels, which, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported. These analyses revealed that common genetic determinants linked to serum Cp levels in this Caucasian patient population are predominantly located within the CP locus. The three most significantly associated SNPs are all intronic and in strong LD with each other. In addition, previous studies have shown that plasma concentrations of ceruloplasmin are regulated at the post-transcriptional level. Specifically, a cis-regulatory element in the 3′ UTR of the CP transcript called GAIT (IFN-γ-activated inhibitor of translation) leads to selective translational silencing in myeloid cells25, 26.

Despite the modest cis effect of the CP locus, our evaluation of the lead SNP (rs13072552) did not reveal an association with either the risk of CAD or future MACE. The lack of such an association could be due to several factors. For example, rs13072552 explains less than 1% of the variation in serum Cp levels, decreasing the power for detecting an association with cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, serum lipid and inflammatory markers, other genetic factors, and dietary/behavioral factors also contribute to the complex pathophysiology of CAD, MI, and MACE. The subjects used in our study were also recruited from patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization, which results in a study population skewed towards individuals mostly having documented CAD and being treated with medications to lower their risk of future MACE. Such confounders, taken together with the low minor allele frequency of rs13072552 and its modest effects on serum Cp levels, in combination with the recognition that post transcriptional processes play a major role in Cp production, may explain, in part, the negative association of the CP locus with CAD and MACE. Our study is also limited by only including subjects of white European ancestry, and additional studies in other ethnicities and with increased power will be required to determine whether the negative genetic findings hold true. However, it is interesting to note that our observations with Cp are similar to other inflammation-sensitive plasma proteins such as C-reactive protein, where consistent prognostic effects were not confirmed by genetic predisposition of cardiovascular risk in relatively large datasets27. Thus, further studies are also warranted to explore the molecular mechanism underlying the strong association between serum Cp levels and cardiovascular events beyond those observed with alternative acute phase proteins (e.g. hsCRP), leukocyte counts, and traditional cardiac risk factors.

The recent discovery of a potential role for Cp as a catalytic sink for NO consumption in vivo raises new and important questions about the vascular function(s) and clinical utility of this unusual copper-containing protein. A readily available and affordable assay, addition of Cp testing to clinical practice may afford synergistic prognostic value with traditional cardiac risk factors, and alternative inflammation markers like hsCRP, MPO, and leukocyte count. In an era of cost effectiveness, further studies are warranted to determine whether Cp testing may provide value in prioritizing preventive interventions amongst those with unrecognized heightened cardiovascular risks.

CONCLUSION

In subjects undergoing elective cardiac evaluation, serum Cp provides additive risk prediction of long-term adverse cardiac events independent of traditional cardiac risk factors, hsCRP, MPO and leukocyte count. Common genetic variants at the CP locus that are linked to serum Cp levels are not associated with prevalent or incident risk of CAD in this study population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

These studies were supported by grant P01 HL076491 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study GeneBank has been supported in part by NIH grants 1P01HL098055 (S.L.H.), 1R01HL103866 (S.L.H.), 1R01DK080732 (S.L.H.), 1R01DK083359 (P.L.F.), and 1R01HL103931 (W.H.T.). The John & Jennifer Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre investigators are supported by CIHR #MOP--82810 (R.R.), CFI #11966 (R.R.), HSFO #NA6001 (R.McP.), CIHR #MOP172605 (R.McP.), CIHR #MOP77682 (A.F.R.S.). Supplies for Cp testing were provided for by Abbott Laboratories, Inc.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Tang received research grant support from Abbott Laboratories, and served as consultants for Medtronic Inc and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Hazen is named as co-inventor on pending and issued patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics. Dr. Hazen reports he has been paid as a consultant or speaker for the following companies: Cleveland Heart Lab, Inc., Esperion, Liposciences Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., and Pfizer Inc. Dr. Hazen reports he has received research funds from Abbott, Cleveland Heart Lab, Esperion and Liposciences, Inc. Dr. Hazen has the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics from Abbott Laboratories, Cleveland Heart Lab, Inc., Frantz Biomarkers, LLC, and Siemens.

References

- 1.Fox PL, Mazumder B, Ehrenwald E, Mukhopadhyay CK. Ceruloplasmin and cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1735–1744. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiva S, Wang X, Ringwood LA, Xu X, Yuditskaya S, Annavajjhala V, Miyajima H, Hogg N, Harris ZL, Gladwin MT. Ceruloplasmin is a NO oxidase and nitrite synthase that determines endocrine NO homeostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:486–493. doi: 10.1038/nchembio813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orena SJ, Goode CA, Linder MC. Binding and uptake of copper from ceruloplasmin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;139:822–829. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gocmen AY, Sahin E, Semiz E, Gumuslu S. Is elevated serum ceruloplasmin level associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease? Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klipstein-Grobusch K, Grobbee DE, Koster JF, Lindemans J, Boeing H, Hofman A, Witteman JC. Serum caeruloplasmin as a coronary risk factor in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Br J Nutr. 1999;81:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suciu A, Chirulescu Z, Zeana C, Pirvulescu R. Study of serum ceruloplasmin and of the copper/zinc ratio in cardiovascular diseases. Rom J Intern Med. 1992;30:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reunanen A, Knekt P, Aaran RK. Serum ceruloplasmin level and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1082–1090. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunetti ND, Pellegrino PL, Correale M, De Gennaro L, Cuculo A, Di Biase M. Acute phase proteins and systolic dysfunction in subjects with acute myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;26:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Correale M, Brunetti ND, De Gennaro L, Di Biase M. Acute phase proteins in atherosclerosis (acute coronary syndrome) Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6:272–277. doi: 10.2174/187152508785909537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunetti ND, Correale M, Pellegrino PL, Cuculo A, Biase MD. Acute phase proteins in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Correlations with diagnosis, clinical features, and angiographic findings. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang WH, Wu Y, Nicholls SJ, Hazen SL. Plasma myeloperoxidase predicts incident cardiovascular risks in stable patients undergoing medical management for coronary artery disease. Clin Chem. 2011;57:33–39. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.152827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vita JA, Brennan ML, Gokce N, Mann SA, Goormastic M, Shishehbor MH, Penn MS, Keaney JF, Jr, Hazen SL. Serum myeloperoxidase levels independently predict endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation. 2004;110:1134–1139. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140262.20831.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eiserich JP, Baldus S, Brennan ML, Ma W, Zhang C, Tousson A, Castro L, Lusis AJ, Nauseef WM, White CR, Freeman BA. Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science. 2002;296:2391–2394. doi: 10.1126/science.1106830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu-Soud HM, Hazen SL. Nitric oxide modulates the catalytic activity of myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5425–5430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marceau N, Aspin N. Distribution of ceruloplasmin-ceruloplasmin-bound 67 Cu in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1972;222:106–110. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frieden E, Hsieh HS. The biological role of ceruloplasmin and its oxidase activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1976;74:505–529. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3270-1_43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh TK. Serum ceruloplasmin in acute myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. 1992;47:321–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manttari M, Manninen V, Huttunen JK, Palosuo T, Ehnholm C, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Serum ferritin and ceruloplasmin as coronary risk factors. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1599–1603. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atanasiu R, Dumoulin MJ, Chahine R, Mateescu MA, Nadeau R. Antiarrhythmic effects of ceruloplasmin during reperfusion in the ischemic isolated rat heart. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;73:1253–1261. doi: 10.1139/y95-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chahine R, Mateescu MA, Roger S, Yamaguchi N, de Champlain J, Nadeau R. Protective effects of ceruloplasmin against electrolysis-induced oxygen free radicals in rat heart. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:1459–1464. doi: 10.1139/y91-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paradis M, Gagne J, Mateescu MA, Paquin J. The effects of nitric oxide-oxidase and putative glutathione-peroxidase activities of ceruloplasmin on the viability of cardiomyocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:2019–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tapryal N, Mukhopadhyay C, Das D, Fox PL, Mukhopadhyay CK. Reactive oxygen species regulate ceruloplasmin by a novel mRNA decay mechanism involving its 3′-untranslated region: implications in neurodegenerative diseases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1873–1883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukhopadhyay CK, Mazumder B, Lindley PF, Fox PL. Identification of the prooxidant site of human ceruloplasmin: a model for oxidative damage by copper bound to protein surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11546–11551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla N, Maher J, Masters J, Angelini GD, Jeremy JY. Does oxidative stress change ceruloplasmin from a protective to a vasculopathic factor? Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazumder B, Sampath P, Fox PL. Translational control of ceruloplasmin gene expression: beyond the IRE. Biol Res. 2006;39:59–66. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampath P, Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL. Transcript-selective translational silencing by gamma interferon is directed by a novel structural element in the ceruloplasmin mRNA 3′ untranslated region. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1509–1519. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1509-1519.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, Bis JC, Eiriksdottir G, Lu C, Pellikka N, Wallaschofski H, Kettunen J, Henneman P, Baumert J, Strachan DP, Fuchsberger C, Vitart V, Wilson JF, Pare G, Naitza S, Rudock ME, Surakka I, de Geus EJ, Alizadeh BZ, Guralnik J, Shuldiner A, Tanaka T, Zee RY, Schnabel RB, Nambi V, Kavousi M, Ripatti S, Nauck M, Smith NL, Smith AV, Sundvall J, Scheet P, Liu Y, Ruokonen A, Rose LM, Larson MG, Hoogeveen RC, Freimer NB, Teumer A, Tracy RP, Launer LJ, Buring JE, Yamamoto JF, Folsom AR, Sijbrands EJ, Pankow J, Elliott P, Keaney JF, Sun W, Sarin AP, Fontes JD, Badola S, Astor BC, Hofman A, Pouta A, Werdan K, Greiser KH, Kuss O, Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Thiery J, Jamshidi Y, Nolte IM, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Volzke H, Parker AN, Aspelund T, Bates D, Young L, Tsui K, Siscovick DS, Guo X, Rotter JI, Uda M, Schlessinger D, Rudan I, Hicks AA, Penninx BW, Thorand B, Gieger C, Coresh J, Willemsen G, Harris TB, Uitterlinden AG, Jarvelin MR, Rice K, Radke D, Salomaa V, Willems van Dijk K, Boerwinkle E, Vasan RS, Ferrucci L, Gibson QD, Bandinelli S, Snieder H, Boomsma DI, Xiao X, Campbell H, Hayward C, Pramstaller PP, van Duijn CM, Peltonen L, Psaty BM, Gudnason V, Ridker PM, Homuth G, Koenig W, Ballantyne CM, Witteman JC, Benjamin EJ, Perola M, Chasman DI. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 2011;123:731–738. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.