Abstract

Many research and commercial applications use a synthetic substrate which is seeded with cells in a serum-containing medium. The surface properties of the material influence the composition of the adsorbed protein layer, which subsequently regulates a variety of cell behaviors such as attachment, spreading, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. In this study, we examined the relationships among cell attachment, spreading, cytoskeletal organization, and migration rate for MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts on glass surfaces modified with –SOx, –NH2, –N+(CH3)3, –SH, and –CH3 terminal silanes. We also studied the relationship between cell spread area and migration rate for a variety of anchorage-dependent cell types on a model polymeric biomaterial, poly(acrylonitrile-vinylchloride). Our results indicated that MC3T3-E1 osteoblast behavior was surface chemistry dependent, and varied with individual functional groups rather than general surface properties such as wettability. In addition, cell migration rate was inversely related to cell spread area for MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts on a variety of silane-modified surfaces as well as for different anchorage-dependent cell types on a model polymeric biomaterial. Furthermore, the data revealed significant differences in migration rate among different cell types on a common polymeric substrate, suggesting that cell type–specific differences must be considered when using, selecting, or designing a substrate for research and therapeutic applications.

Keywords: cell attachment, cell spreading, migration rate, model surfaces, MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts

INTRODUCTION

In many applications, synthetic substrates are seeded with cells in a serum-containing medium, resulting in the formation of a complex surface layer of adsorbed proteins which subsequently mediates interactions with cells. Among these proteins are fibronectin and vitronectin, which contain the RGD amino acid sequence recognized by cell-surface integrin receptors. Integrin binding is followed by receptor aggregation and the accumulation of actin and integrin binding proteins at cytoplasmic domains which provide foci for the nucleation of actin microfilaments. These early events promote several structural changes in cells such as spreading and cytoskeletal reorganization. In addition, they initiate signaling cascades which regulate longer-term events such as protein production.1–3 Although the precise mechanisms of these pathways have not yet been fully elucidated, such integrin-related events as cell spreading and cell morphology have been correlated with changes in cell survival, cell proliferation, and cellular differentiation.4–6

Many of the biomaterials currently in use as therapeutic implants have been selected through trial and error testing using animal models. An alternative approach uses model surfaces to evaluate the influence of specific chemical groups or material surface properties on protein adsorption and cellular interactions using in vitro assay systems. Studies have indicated that surface properties of biomaterials influence the type, quantity, and conformation of adsorbed proteins.7 Differences in the adsorbed layer, particularly in surface density and the conformation of cell binding proteins, undoubtedly influence cell signaling and underlie cell behavior at the material–tissue interface. Developing an understanding of these interrelationships will facilitate the design of biomaterials which actively promote desired cellular responses such as proliferation, migration, or differentiation, and will aid in developing better in vitro assays of biomaterial compatibility.

Studies indicate that cell attachment and cell spreading are generally greater on certain hydrophilic surfaces relative to hydrophobic surfaces.8–11 Likewise, cytoskeletal organization and cell morphology are regulated by surface wettability.9,12 Fewer studies, however, have examined the influence of protein-coated model surfaces on cell proliferation, migratory activity, and gene expression.

Cell migratory behavior is an important aspect of the colonization of three-dimensional substrates, of the wound-healing response, and in other such areas as developmental biology and cancer research. Not surprisingly, many investigators are studying the biology of cell migration and the influence of different surface ligands on the migratory process.13–16 However, to the best of our knowledge no study has examined cell migration on a broad range of surface chemistries treated uniformly with a complex protein solution such as serum. Therefore, we examined the relationships among cell attachment, cell spreading, cytoskeletal organization, and cell migration rate of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells on serum-treated model silane surfaces of varying wettability and charged surface functional groups. In addition, we examined the relationship between cell spread area and cell migration rate using a variety of different anchorage-dependent cell types cultured on a common substrate exposed to a serum-containing medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model surface preparation

Glass coverslips (No. 2, 25 mm in diameter; Fisher, Pitts-burgh, PA) were modified with silane coupling reagents as previously described.17–19 Five different surface chemistries were generated, including oxidized thiol (≡Si–(CH2)3SOx), quaternary amine (≡Si–CH2N+(CH3)3I−), amine (≡Si–(CH2)3NH2), thiol (≡Si–(CH2)3SH), and methyl (=Si(CH3)2. The characterization of these model surfaces by static water contact angle, pH-dependent water contact angle, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) has been previously described.19 All surfaces were used immediately following modification.

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells and NIH 3T3 Swiss Albino fibroblasts (ATCC, CCL 92) were routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma). Astrocytes, meningeal cells, and dermal fibroblasts were isolated from P1 rats as previously described and cultured in DMEM with 10% BCS and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin. Experiments with astrocytes, meningeal cells, and dermal fibroblasts were performed prior to the fourth passage. These cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% BCS and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin.20 For routine culture, all cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere with fresh medium added every 2 days.

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell attachment, spreading, and cytoskeletal staining

Silane-modified surfaces were placed in six-well Low Cluster plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA), and covered with 2.5 mL of DMEM with 10% BCS and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin. Simultaneously, confluent monolayers of cells were dissociated with 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without divalent ions, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS. Cells were counted in a hemocytometer and diluted to 150,000 cells/mL. A 200-μL aliquot of cell suspension (30,000 cells) was added to each well, gently mixed, and incubated for 6 h. The cells were then fixed with 3% para-formaldehyde in PBS, rinsed, and stored in PBS.

Cell attachment was determined by counting the number of adherent cells in 30 separate ×100 viewing fields on each of four independent surfaces using a phase-contrast microscope. Each ×100 viewing field was 2.9 mm2 so that 17.7% of the total surface area was analyzed for each surface. Cell area was calculated from digitized images recorded with a CCD camera using NIH Image software. Each cell was also modeled as an ellipse and the cell aspect ratio calculated as the ratio of the major axis to the minor axis. Area and aspect ratio measurements were performed on 15 cells from each of four independent samples of each modified surface.

The cells were stained with rhodamine phalloidin (5 U/mL; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), mouse anti-human vinculin monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; Sigma), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse monoclonal antibody (1:20 dilution; CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA) as previously described.19 Fluorescence images were taken on a Zeiss Axioplan II microscope with a ×40 objective using standard rhodamine and fluorescein filters.

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell migration on silane-modified surfaces

For each migration experiment, the appropriate silanized surface was prepared on a 25-mm glass coverslip, placed into a Leiden coverslip dish (Medical Systems Corp., Green-vale, NY), and covered with DMEM with 10% BCS, and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin. Simultaneously, a confluent flask of MC3T3-E1 cells was dissociated using 0.02% EDTA in PBS without divalent ions, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS. The cells were counted in a hemocytometer and diluted to approximately 100,000 cells/mL. A 100-μLl aliquot of cells (10,000 cells) was added to the medium in the Leiden coverslip dish and incubated at 37°C for 2 h to allow attachment. The coverslip dish was rinsed three times and covered with minimal essential medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT) with 10% BCS, 5 mM HEPES (Sigma), and 50 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin. The coverslip dish was placed in a Leiden Micro-Incubator (Medical Systems Corp.) on the stage of a Nikon Diaphot microscope and observed under bright-field illumination using a ×10 objective. Culture temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.2°C with a temperature controller (TC102; Medical Systems Corp.) Cell migratory behavior was recorded for 6 h using a time-lapse video recorder (AG-6740; Panasonic) and quantitatively analyzed during playback with an image processor (Argus-2; Hamamatsu). Cell migration distance was determined by measuring the total distance traveled by each cell’s nucleus during the playback period. Cell migration rate was calculated as the cell migration distance divided by the 6-h recording time. Two separate migration experiments were performed for each modified surface, with a minimum of 15 total cells analyzed for each surface.

Polymer thin film preparation and characterization

A 6% (w/v) solution of poly(acrylonitrile-vinylchloride) (PAN-PVC) (a gift from Cytotherapeutics, Inc.) was prepared in a 50:50 mixture of dimethylformamide and acetone. Thin films were spun cast on 25-mm glass coverslips at 1500 rpm for 5 s, then 4000 rpm for an additional 5 s. The film was characterized by sessile drop water contact angle measurements, XPS, and attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy.

Migration/area experiments on PAN-PVC thin films

Two separate migration experiments for each of five different anchorage-dependent cell types were performed as described for MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells, with the exception that 0.05% trypsin in Hank’s balanced salt solution with 0.53 mM EDTA (Gibco) was used for cell dissociation and inactivated by resuspending the cell pellet in medium with 10% serum. During one experiment for each cell type, three additional PAN-PVC thin film surfaces were seeded in a six-well Low-Cluster plate, cultured for 6 h, and fixed with 0.1% gluteraldehyde. Cell area was determined for 10 cells from each of the three independent surfaces for each cell type.

Statistical analysis

The data for attachment, spreading, aspect ratio, and migration rate assays were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s method for multiple comparisons; p < .05 was defined as significant. All results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell attachment, spreading, and cytoskeletal organization on model silane surfaces

Cell attachment at 6 h postseeding is shown in Figure 1. The number of adherent cells was significantly higher on thiol surfaces relative to all others. The number of adherent cells was intermediate on oxidized thiol and methyl surfaces and lowest on quaternary amine and amine surfaces relative to oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces.

Figure 1.

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell attachment to silane-modified surfaces at 6 h in 10% serum-containing medium. Static water contact angles measured by the sessile drop method using distilled water buffered with 1.45 mM sodium phosphate monobasic and 8.1 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, pH 7.5, are shown beneath the x-axis legend. n = 4 surfaces.

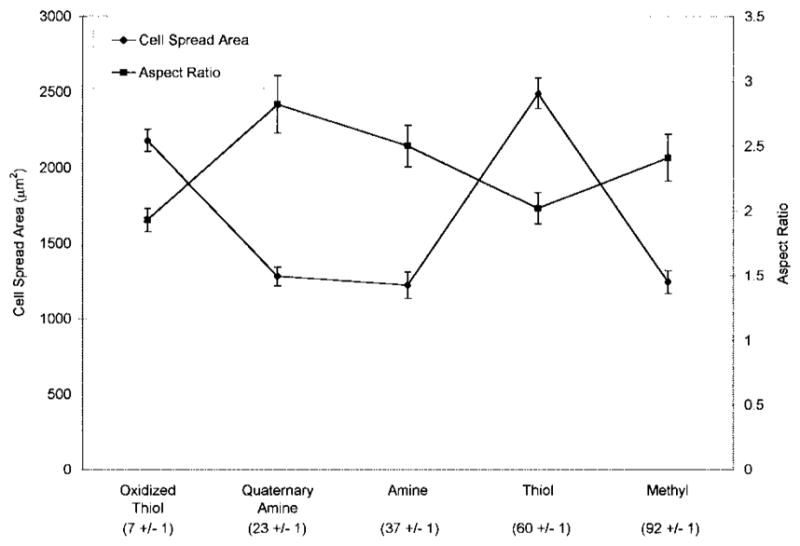

Cells on oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces displayed a circular, well-spread morphology characterized by significantly higher cell area relative to cells on quaternary amine, amine, and methyl surfaces (Fig. 2). Cells on quaternary amine, amine, and methyl surfaces typically displayed a bipolar, spindle-shaped morphology characterized by low cell area and high aspect ratio. Cell aspect ratio was significantly higher on quaternary amine surfaces relative to cells on oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces.

Figure 2.

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell area and aspect ratio on silane-modified surfaces at 6 h in 10% serum-containing medium. Static water contact angles measured by the sessile drop method using distilled water buffered with 1.45 mM sodium phosphate monobasic and 8.1 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, pH 7.5, are shown beneath the x-axis legend. n = 4 surfaces.

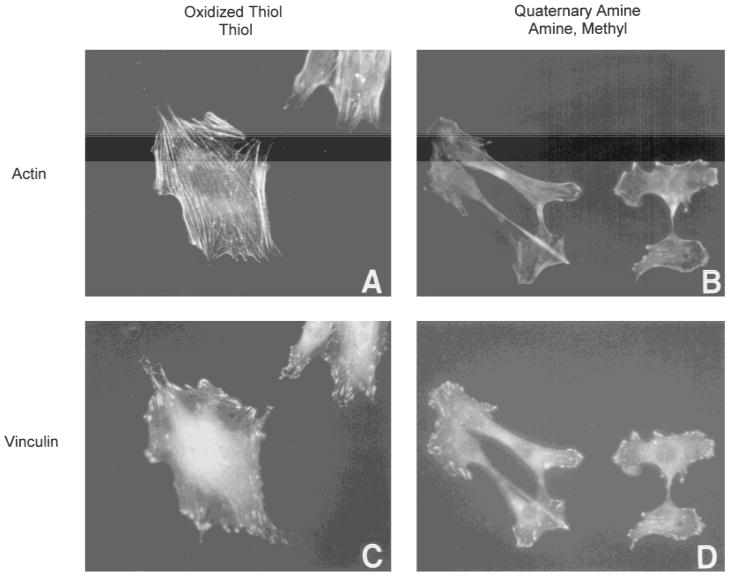

Figure 3 shows representative photographs of cell morphology on oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces (a,c) and quaternary amine, amine, and methyl surfaces (b,d) fluorescently stained for actin microfilaments (a,b) and the focal adhesion protein vinculin (c,d). Cells on thiol and oxidized thiol surfaces displayed a complex network of actin stress fibers throughout the cell, associated with numerous focal adhesions positively stained for vinculin. Cells on quaternary amine, amine, and methyl surfaces displayed prominent actin stress fibers at the cell periphery running along the long axis of the cell with reduced actin staining within the cell interior. Similarly, vinculin-positive focal adhesions were restricted to one or two regions of the cell periphery which appeared to correspond to a leading edge and tail region.

Figure 3.

Cytoskeletal organization of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells representative of the predominant morphologies on oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces (a,c) and amine, quaternary amine, and methyl surfaces (b,d). Cells were double-labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin for actin (a,b) and by indirect immunofluorescence for vinculin (c,d).

MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell migration on model silane surfaces

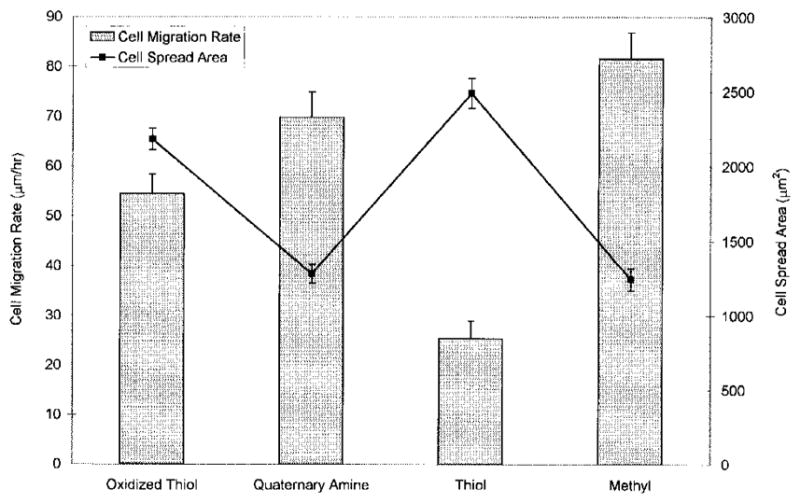

MC3T3-E1 cell migration rate was significantly lower on thiol surfaces relative to oxidized thiol, quaternary amine, and methyl surfaces (Fig. 4). The line graph of cell area is reproduced in Figure 4 to show the inverse relationship between migration rate and cell area. Relatively higher migration rates on quaternary amine and methyl surfaces were associated with reduced cell area, whereas lower migration rates on oxidized thiol and thiol surfaces were associated with increased cell area. Migration data for cells on amine surfaces were not included because these cells transiently detached from the surfaces at the beginning of migration experiments. We believe this resulted from a slight thermal current created when the heating coil was first activated to increase the temperature of the Leiden migration chamber from room temperature to 37°C.

Figure 4.

Cell spread area and migration rate of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells on silane-modified surfaces.

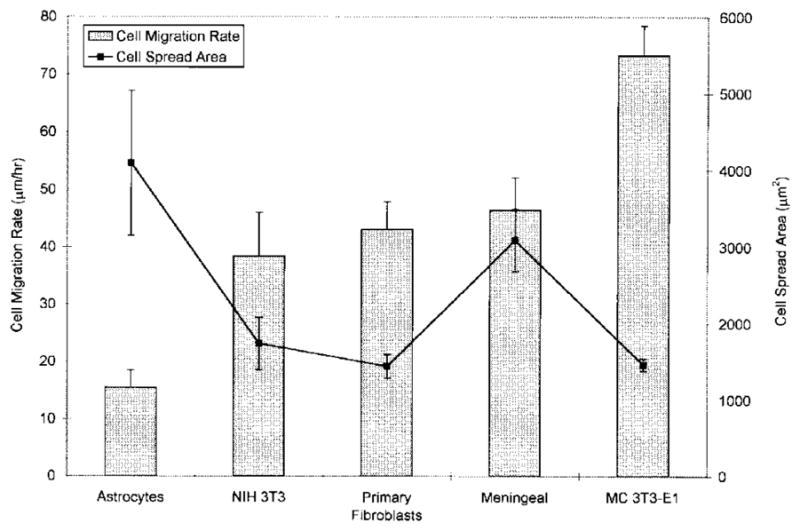

Multiple cell-type migration on PAN-PVC thin films

PAN-PVC thin films had a water contact angle of 76° and ATR-FTIR spectra matching those of the bulk polymer. In general, the inverse relationship previously observed between cell spread area and migration rate was maintained (Fig. 5). Astrocytes displayed significantly lower migration rate relative to all other cell types, whereas MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell migration rate was significantly greater than all other cell types. Astrocyte spread cell area was significantly greater than NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, dermal fibroblasts, and MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells.

Figure 5.

Cell spread area and migration rate of different cell types on PAN-PVC thin films.

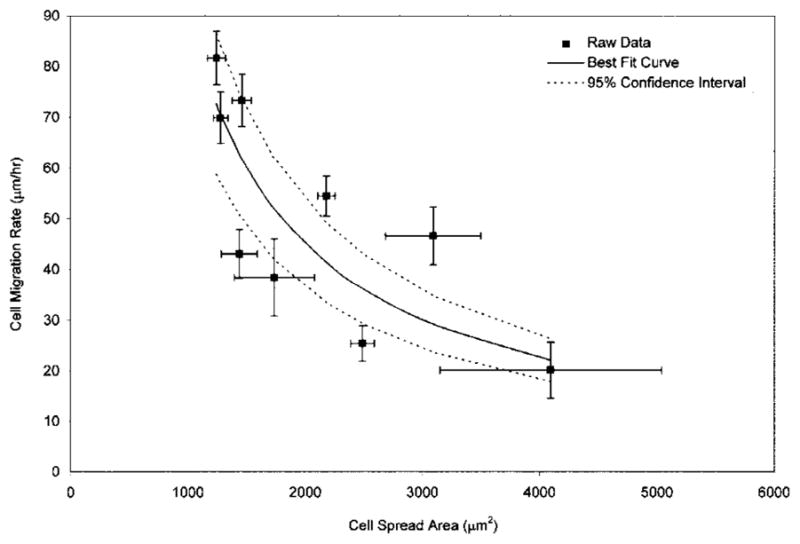

The data presented in Figures 4 and 5 can be combined and displayed as shown in Figure 6, where the migration rate is plotted as a function of the cell area. The solid line illustrates a best-fit curve for the data to the form y = constant · 1/x where the best fit constant equals 90,351 μm3/h. The dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals for the data.

Figure 6.

Cell migration rate plotted as a function of cell spread area. The best-fit curve (solid line) incorporates data obtained from MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts on silane-modified surfaces and multiple cell types on PAN-PVC thin films; 95% confidence intervals for the best-fit curve are illustrated with dashed lines.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationships among cell attachment, cell spread area, cytoskeletal organization, and cell migration rate on model surfaces treated with a serum-containing media commonly used in culture systems. Glass coverslips were prepared with five different surface chemistries providing varying ranges of wettability and charge. Characterization of these model surfaces by contact angle techniques and XPS has been described previously.19 The results of our studies using MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts on model silane surfaces revealed that several MC3T3-E1 cell behaviors including cell attachment efficiency, spread cell area or cell morphology, cytoskeletal organization, and cell migration rate change as a function of a particular serum-treated silane surface chemistry.

Several studies have demonstrated preferential attachment and growth of cells on hydrophilic surfaces patterned on hydrophobic backgrounds and hydrophilic regions of gradient surfaces.9,21–23 Likewise, enhanced cell spreading and increased actin stress fiber organization have been observed on hydrophilic surfaces relative to hydrophobic surfaces.8,11,24 A recent study in our laboratory also observed significantly higher NIH 3T3 fibroblast cell attachment, spreading, and actin stress fiber formation on hydrophilic model silane surfaces preadsorbed with 5% serum.19 In the present study, the cellular responses of MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cells did not display a consistent trend of behavior in relation to surface wettability on a range of serum-treated model silane surfaces, but rather varied as a function of particular functional groups.

There are several potential explanations for the differences observed between the studies cited above. Clearly, cell type–specific differences in membrane properties such as phospholipid composition and integrin receptor expression influence cellular interactions with surfaces. In addition, differences in the chain length of molecules used to prepare model surfaces as well as differences in serum concentration used in various experimental designs directly influence cell attachment and cell spreading.25,26

Although our MC3T3-E1 studies did not reveal a simple general principle relating material surface chemistry to the behaviors we examined, an inverse relationship was observed between cell spread area and cell migration rate. Several groups have previously reported on a similar relationship between cytoskeletal assembly and cell migration.27–29 Using genetically engineered cells, increased vinculin expression has been shown to reduce cell motility, whereas vinculin-null mutant cells migrate much more rapidly than wild-type controls.27,28 Similarly, enhanced cell spreading and pp125FAK tyrosine phosphorylation have been shown to be associated with decreased cell migration.29

We extended our studies to examine the relationship between cell migration rate and cell spread area using a model biomaterial surface and anchorage-dependent cell types that reside in different tissue compartments of the body. PAN-PVC was selected as a model substrate because of its wide use in bioprocessing and encapsulated tissue engineering applications. We chose the cell types based on their likelihood of encountering the surface of a PAN-PVC implant following implantation in the central nervous system (CNS) or within peripheral tissues.30,31 Our results indicate that anchorage-dependent cell types exhibit significant differences in migratory velocity following attachment to this common substrate exposed to the same protein-containing solution. These results are most likely produced by differential expression of integrin receptors among different cell types. Integrin expression has been shown to vary among different cell populations within the CNS.32 As in our MC3T3-E1 studies, cell area was inversely related to cell migration rate.

We combined the data from all of our migration and cell area experiments (Fig. 6) and modeled this data as an inverse relationship, where:

The best possible fit of the data to this relationship (solid line in Fig. 6) results in a constant of 90,351 μm3/h. We hypothesize that this value represents a cellular volumetric flow rate constant which characterizes the relationship between migration rate and cell spread area for a variety of anchorage-dependent cell types on a variety of model surfaces. The variability observed between some of the data points and the best-fit curve presented in Figure 6 is most likely due to our use of five different cell types and five different model surfaces.

Lauffenburger and coworkers developed a model demonstrating that cell migration rate is a function of cell-substrate attachment strength.16 Cell-substrate attachment strength may be regulated by surface ligand density, integrin expression levels, and integrin-ligand binding affinity.33 Maximum cell migration was observed at intermediate levels of cell-substrate attachment strength.16 Our observations are consistent with this model. The variation in MC3T3-E1 osteoblast-like cell migration rate on different silane-modified surfaces is most likely attributable to differences in the quantity and conformation of adsorbed adhesive ligands from serum. Fibronectin adsorption from serum has been shown to vary among copolymers with different compositions of hydroxyethyl methacrylate and ethylmethacrylate.25 In addition, studies with monoclonal antibodies have also indicated differences in the conformation of fibronectin and vitronectin adsorbed to different types of tissue culture polystyrene.34 In our investigation of the migratory behavior of multiple cell types seeded on PAN-PVC, the differences in migration rate are most likely attributable to differences in the level of expression of integrin receptors among the different cell types, since the adsorbed layer was constant.

In summary, we presented several studies that examined the combined effect of serum protein–treated chemically defined surfaces on the behavior of anchorage-dependent cells. Our data indicate that such MC3T3-E1 cell behaviors as cell attachment efficiency, spreading behavior, actin stress fiber formation, and cell migration rate are material surface chemistry dependent, and further suggest that surface engineering will be an effective tool for eliciting certain sets of cell behaviors for at least short-term in vitro or clinical applications. In addition, our results confirm the reports of others that cell migration rate is reciprocally related to cell spreading. Whereas such a relationship has been demonstrated previously by varying the adsorbed protein layer, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that this reciprocal trend spans several different cell types of different embryonic origins. This general principle of cell behavior may be useful in optimizing implant design for such tissue engineering applications as regeneration scaffolds, where the rate of initial migratory behavior determines the time frame for colonization and subsequent restoration of tissue function. The results underscore the importance of studies geared toward elucidating the relationships between cell behavior and interfacial chemistry. In the future, it may be possible to prepare synthetic substrates with surface properties that promote specific cell behaviors for therapeutic applications.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: Center for Biopolymers at Interfaces, University of Utah

Contract grant sponsor: Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah

Contract grant sponsor: W. M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles

References

- 1.Clark EA, Brugge JS. Integrins and signal transduction pathways: the road taken. Science. 1995;268:233–239. doi: 10.1126/science.7716514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Coso OA, Gutkind JS, Burbelo PD, Akiyama SK, Yamada KM. Integrin function: molecular hierarchies of cytoskeletal and signaling molecules. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:791–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Ze’ev A, Robinson GS, Bucher NLR, Farmer SR. Cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions differentially regulate the expression of hepatic and cytoskeletal genes in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:2161–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singhvi R, Kumar A, Lopez GP, Stephanopoulos GN, Wang DIC, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Engineering cell shape and function. Science. 1994;264:696–698. doi: 10.1126/science.8171320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrade JD, Hlady V. Protein adsorption and materials bio-compatibility: a tutorial review and suggested hypotheses. Adv Polym Sci. 1986;79:1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schakenraad JM, Busscher HJ, Wildevuur CRH, Arends J. The influence of substratum surface free energy on growth and spreading of human fibroblasts in the presence and absence of serum proteins. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20:773–784. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruardy TG, Schakenraad JM, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Adhesion and spreading of human skin fibroblasts on physiochemically characterized gradient surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29:1415–1423. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820291113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healy KE, Thomas CH, Rezania A, Kim JE, McKeown PJ, Lom B, Hockberger PE. Kinetics of bone cell organization and mineralization on materials with patterned surface chemistry. Biomaterials. 1996;17:195–208. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altankov G, Grinnell F, Groth T. Studies on the biocompatibility of materials: fibroblast reorganization of substratum-bound fibronectin on surfaces varying in wettability. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;30:385–391. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199603)30:3<385::AID-JBM13>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juliano DJ, Saavedra SS, Truskey GA. Effect of the conformation and orientation of adsorbed fibronectin on endothelial cell spreading and the strength of adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993;27:1103–1113. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huttenlocher A, Sanborg RR, Horwitz AF. Adhesion in cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:697–706. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauffenburger DA, Horowitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell. 1996;84:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman SL, Risse G, von der Mark K. The E8 subfragment of laminin promotes locomotion of myoblasts over extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:799–809. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiMilla PA, Stone JA, Quinn JA, Albelda SM, Lauffenburger DA. Maximal migration of human smooth muscle cells on fibronectin and type IV collagen occurs at an intermediate attachment strength. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:729–737. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin YS, Hlady V. The desorption of ribonuclease A from charge density gradient surfaces studied by spatially-resolved total internal reflection fluorescence. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 1995;4:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0927-7765(94)01150-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Hlady V. Chemical pattern on silica surface prepared by UV irradiation of 3-mercaptopropyltriethoxy silane layer: surface characterization and fibrinogen adsorption. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 1996;8:25–37. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7765(96)01298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb K, Hlady V, Tresco PA. The relative importance of surface wettability and charged functional groups on NIH 3T3 fibroblast attachment, spreading, and cytoskeletal organization. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;41:422–430. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19980905)41:3<422::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noble M, Fok-Seang J, Cohen J. Glia are a unique substrate for the in vitro growth of central nervous system neurons. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1892–1903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01892.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenger DA, Georger JH, Dulcey CS, Hickman JJ, Rudolph AS, Nielsen TB, McCort SM, Calvert JM. Coplanar molecular assemblies of amino- and perfluorinated alkylsilanes: characterization and geometric definition of mammalian cell adhesion and growth. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:8435–8442. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georger JH, Stenger DA, Rudolph AS, Hickman JJ, Dulcey CS, Fare TL. Coplanar patterns of self-assembled monolayers for selective cell adhesion and outgrowth. Thin Sol Films. 1992;210:716–719. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britland S, Clark P, Connolly P, Moores G. Micropatterned substratum adhesiveness: a model for morphogenetic cues controlling cell behavior. Exp Cell Res. 1992;198:124–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Valk P, van Pelt AWJ, Busscher HJ, de Jong HP, Wildevuur CRH, Arends J. Interaction of fibroblasts and polymer surfaces: relationship between surface free energy and fibroblast spreading. J Biomed Mater Res. 1983;17:807–817. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horbett TA, Schway MB. Correlations between mouse 3T3 cell spreading and serum fibronectin adsorption on glass and hydroxyethylmethacrylate-ethylmethacrylate copolymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1988;22:763–793. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820220903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schotchford CA, Barley M, Hughes K, Cooper E, Leggett GJ, Downes S. Osteoblast growth on alkanethiol self assembled monolayers: influences of chain length and terminal chemistry. Transactions of the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Biomaterials; 1997. p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez JLR, Geiger B, Salomon D, Ben-Ze’ev A. Overexpression of vinculin suppresses cell motility in BALB/c 3T3 cells. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1992;22:127–134. doi: 10.1002/cm.970220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coll JL, Ben-Ze’ev A, Ezell RM, Fernandez JLR, Baribault H, Oshima RG, Adamson ED. Targeted disruption of vinculin genes in F9 and embryonic stem cells changes cell morphology, adhesion, and locomotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9161–9165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sankar S, Mahooti Brooks N, Hu G, Madri JA. Modulation of cell spreading and migration by pp125FAK phosphorylation. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:601–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colton CK, Avgoustiniatos ES. Bioengineering in development of the hybrid artificial pancreas. Trans ASME. 1991;113:152–170. doi: 10.1115/1.2891229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentile FT, Doherty EJ, Rein DH, Shoichet MS, Winn SR. Polymer science for macroencapsulation of cells for central nervous system transplantation. Reactive Polymers. 1995;25:207–227. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tawil NJ, Wilson P, Carbonetto S. Expression and distribution of functional integrins in rat CNS glia. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:436–447. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palecek SP, Loftus JC, Ginsberg MH, Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Integrin-ligand binding properties govern cell migration speed through cell-substratum adhesiveness. Nature. 1997;385:537–540. doi: 10.1038/385537a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Underwood PA, Steele JG, Dalton BA. Effects of polystyrene surface chemistry on the biological activity of solid phase fibronectin and vitronectin, analyzed with monoclonal antibodies. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:793–803. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]