Abstract

PURPOSE

Medication nonadherence, inconsistent patient self-monitoring, and inadequate treatment adjustment exacerbate poor disease control. In a collaborative, team-based, care management program for complex patients (TEAMcare), we assessed patient and physician behaviors (medication adherence, self-monitoring, and treatment adjustment) in achieving better outcomes for diabetes, coronary heart disease, and depression.

METHODS

A randomized controlled trial was conducted (2007–2009) in 14 primary care clinics among 214 patients with poorly controlled diabetes (glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c] ≥8.5%) or coronary heart disease (blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL) with coexisting depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score ≥10). In the TEAMcare program, a nurse care manager collaborated closely with primary care physicians, patients, and consultants to deliver a treat-to-target approach across multiple conditions. Measures included medication initiation, adjustment, adherence, and disease self-monitoring.

RESULTS

Pharmacotherapy initiation and adjustment rates were sixfold higher for antidepressants (relative rate [RR] = 6.20; P <.001), threefold higher for insulin (RR = 2.97; P <.001), and nearly twofold higher for antihypertensive medications (RR = 1.86, P <.001) among TEAMcare relative to usual care patients. Medication adherence did not differ between the 2 groups in any of the 5 therapeutic classes examined at 12 months. TEAMcare patients monitored blood pressure (RR = 3.20; P <.001) and glucose more frequently (RR = 1.28; P = .006).

CONCLUSIONS

Frequent and timely treatment adjustment by primary care physicians, along with increased patient self-monitoring, improved control of diabetes, depression, and heart disease, with no change in medication adherence rates. High baseline adherence rates may have exerted a ceiling effect on potential improvements in medication adherence.

Keywords: Treatment adjustment, medication adherence, multicondition, diabetes, coronary heart disease, depression, collaborative care, treat-to-target, chronic care model, TEAMcare

INTRODUCTION

Patients with multiple chronic diseases experience unfavorable health outcomes1–4 and give rise to challenges in patient care and medical costs.5,6 Competing demands and fragmented care contribute to poor disease control among patients with multiple conditions.7–9 Such patients often seek care from various clinicians, receive complex medication regimens, and are at high risk of harmful drug interactions.10 Primary care physicians manage these patients with limited support for care coordination.11 Clinical uncertainty, inadequate patient self-monitoring, deficiencies in medication adherence, and delayed treatment adjustments contribute to unsatisfactory disease control among complex chronic disease patients.12–16 Thus, it is not surprising that inadequate medication management is found in one-half to two-thirds of patients with uncontrolled diabetes and coronary heart disease.17 When comorbid depression is also present, which occurs in up to 20% of patients with diabetes, health care costs and risks of adverse outcomes are further magnified.18–25 Depressed chronic disease patients are less likely to adhere to prescribed medication and self-care regimens.26,27

Chronic disease care management interventions have mainly focused on single conditions, even though patient adherence decreases as the number of prescribed medication increases.28,29 We developed a patient-centered, team-based intervention to improve patient self-monitoring, medication adherence, and timeliness of treatment adjustment among patients with multiple conditions, depression, and poorly controlled diabetes or coronary heart disease.30 As previously reported, the TEAMcare group improved glycated hemoglobin levels, low-density lipoprotein levels, blood pressures, and depression outcomes31 relative to a group receiving usual care. Moreover, this intervention enhanced quality of life and reduced disability.32 We hypothesized that possible mechanisms for improving disease control outcomes included patient self-monitoring, patient medication adherence, and physician treatment adjustment. This article examines these modifiable patient and clinician factors among complex patients and assesses how a collaborative, team-based, care management program differed from usual care.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

Group Health Cooperative (Group Health) is an integrated health care system with 640,000 enrollees in Washington State. From May 2007 to October 2009, we recruited patients and primary care physicians from 14 Group Health primary care clinics. Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and Group Health approved this study. For a detailed description of study methods, see Katon et al.33

Patients

We identified patients with poorly controlled glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (≥8.5%), elevated blood pressure ( >140/90 mm Hg), or elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values ( >130 mg/dL) from electronic health records. Eligibility also required a depression score of 10 or higher on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).34 Exclusion criteria were terminal illness, residence in long-term care, severe hearing loss, planning bariatric surgery, pregnancy or nursing, ongoing psychiatric care, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, antipsychotic or mood stabilizer medication use, or mental confusion suggesting dementia. After randomization into TEAMcare group, usual care patients were advised to consult their primary care physician to receive care for depression, diabetes, or coronary heart disease. Since 2006, primary care services at Group Health have been organized as a medical home model. Patients receiving usual care obtain most of their health care needs from their primary care physicians and team members (medical assistants, nurses, and clinical pharmacists). Patients can self-refer or be referred for specialty services, including mental health.

For each intervention and usual care patient, physicians received notifications of depression, poor medical disease control, and laboratory test results at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. Physicians were responsible for medication management for both care management and usual care patients.

Randomization and Intervention

After obtaining informed consent and confirming study eligibility via baseline interview, patients were randomly assigned to treatment group using a permuted block design with randomly selected block sizes of 4, 6, and 8 patients. After baseline evaluation, a study nurse contacted patients assigned to TEAMcare to initiate treatment.

Intervention: Multi-Condition Collaborative Care Management (TEAMcare)

The intervention distilled elements from collaborative care for depression,35,36 the chronic care model,37,38 and treat-to-target strategies initially developed for diabetes.39 An integrated and consistent approach was applied systematically across 3 chronic illnesses (diabetes, depression, and coronary heart disease).

A nurse care manager was responsible for enhancing patient self-management, responsiveness and continuity of care, systematic follow-up, and working with the primary care physicians (Table 1). Patients were key members of the team.40 Nurse care managers worked with patients and physicians to identify patient-centered self-care goals and clinical targets and to develop individualized care plans. They motivated patients to carry out specific self-care activities, using morale-boosting, educational, and problem-solving strategies. Nurses tracked patient progress using a care management information system, and they regularly reviewed the caseload with a consulting psychiatrist and internist or family physician. During weekly caseload reviews (treat-to-target reviews), physician consultants recommended treatment adjustments to achieve individualized targets for clinical parameters (eg, PHQ-9 score, blood pressure) and ensured accountability for follow-up of the entire caseload. Care managers ascertained whether the physicians would implement recommendations for treatment changes. In a proactive manner, nurses monitored patients with visits or telephone calls, initially 2 to 3 times a month, administered the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire, reviewed home glucose and blood pressure values and laboratory tests, and enhanced medication adherence. When patients achieved self-care goals and clinical targets, they worked with care managers to formulate maintenance and relapse prevention plans for follow-up with their primary care team. Care managers offered more frequent contacts or scheduled follow-up visits with physicians for patients who failed to meet clinical targets.

Table 1.

Key Elements of Multicondition Collaborative Care Management

| Tasks and Objectives | Process | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Identify goals or target | Collaborate to formulate specific and measurable targets (eg, BP, PHQ-9 [depression], HbA1c or BG, walk number of steps) | Patient, primary care physicians, care managers |

| Support self-care | Motivate, problem-solve to promote self-monitoring, adherence to medications, lifestyle change | Patient; care managers |

| Monitor progress | Systematic, proactive tracking, population-based | Patient, care manager, multi-disciplinary consultant |

| Treat-to-target case reviews | Weekly multidisciplinary caseload review, formulate treatment adjustment recommendations to primary care physician Case-by-case training Accountability for improving outcomes |

Treat-to-target physician consultants, care manager |

| Care coordination | Communicate and coordinate (eg, EHR, telephone, fax, or in person) | Care manager |

BG = blood glucose; BP = blood pressure; EHR = electronic health record; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Self-Monitoring and Medication Adherence

We used automated pharmacy refill data in the 12 months before and after baseline to assess medication adherence by calculating percentage of days in the year that a patient obtained medicines from prescription fills divided by the number of days the patient should have been on the medication derived from a continuous, multiple gaps in therapy method.39 This adherence measure has been validated against serum and urine drug levels, medical costs, and clinical effects, such as blood pressure measures.41,42 The continuous measure of medication gaps was initially calculated for each medication class. Because hyperglycemia, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are often treated with multiple medications, we defined adherence as the average adherence for each prescribed medication class used to treat each disease parameter, weighted by the number of days within each observation window for each medication (ie, the time between the first and last prescription fill).17 The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities questionnaire was adapted to assess the number of days in the prior week that patients measured home blood glucose and blood pressure.43

Treatment Initiation and Adjustment

Medications used in this intervention were predominantly generic, and common first- or second-line agents. In this sample of patients who met criteria for poorly controlled parameters of diabetes, coronary heart disease, and depression, we evaluated whether treatment changes differed between patients receiving usual care and TEAMcare. Pharmacotherapy adjustments were defined by (1) increase in the number of medication classes prescribed, (2) change in dosage for at least 1 medication class, (3) switch to a medication in a different class, or (4) switch to a different medication within the same class during the 12-month intervention. Medication adjustment includes initiations and subsequent treatment changes. We then determined the time to first adjustment.44

Five medication classes were examined: (1) anti-hypertensive medications (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, β-adrenergic blockers, calcium-channel blockers; (2) oral hypoglycemic medications (biguanides, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones), (3) insulin; (4) lipid-lowering medications (statins, fibrates, bile acid resins, ezetimibe, and niacin); and (5) antidepressant medications (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, trazodone, and tricyclics). Combination pills were included in 2 classes (ie, lisinopril and hydrochlorothiazide in ACE inhibitors and diuretics).44 A chart review of all patients filling insulin prescriptions assessed initiation, timing, and insulin titration during the 12-month period. Start of insulin therapy and a change in insulin type, dosage, or use of a sliding scale was recorded as a treatment adjustment.

Blood pressure and HbA1c were measured in person at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, with fasting LDL cholesterol values obtained at baseline and 12 months. Telephone interviewers assessed depression symptoms (PHQ-9) at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months. All laboratory tests were performed at Group Health laboratories and entered into the electronic health record with physician notification.

Statistical Analyses

Cumulative incidence curves were used to describe TEAMcare vs usual care differences in time to first treatment adjustment across 5 medication classes.45 We examined the incidence of adjustment for each medication class for intervals between baseline, 30 days, 60 days, 90 days, and 1 year. We tested for intervention vs usual care differences in overall first treatment adjustment at 1 year using Pearson’s χ2 tests. We used Poisson regression models to estimate the relationship between randomization groups and 1-year rates of adjustment, while controlling for baseline clinical values. Robust (Huber-White) standard errors were used to compute 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for rates and baseline controlled relative rates (RRs). Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Study Participants

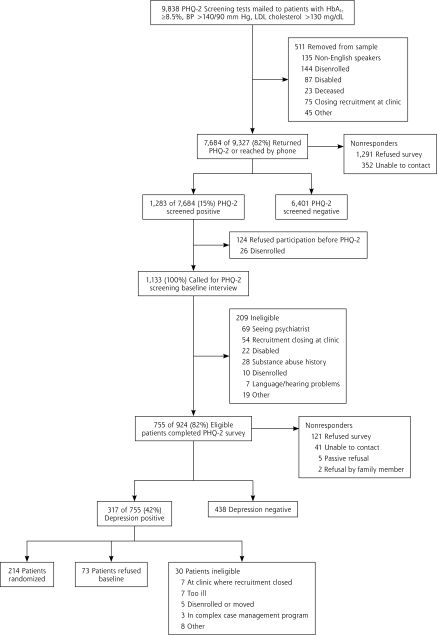

Figure 1 displays the study recruitment flow diagram. Among the 214 patients who were enrolled in the trial, 106 were randomized to the TEAMcare group, and 108 were randomized to the usual care group; 33 were excluded (ie, 16 disenrolled from Group Health Cooperative before 12 months of follow-up and 17 remained enrolled but reported filling their prescriptions outside Group Health). Complete pharmacy data were available for 181 (84.6%) patients (TEAMcare = 91, usual care = 90). The TEAMcare and usual care patient groups showed similar demographic characteristics (mean age = 56.8 years, SD = 11.3; male = 47.6%). At baseline, the 2 groups had similar clinical characteristics and percentage receiving pharmacotherapy, except that more patients in the intervention group than the usual care group received oral hypoglycemic agents (Table 2). During the 12 months, both groups had similar numbers of outpatient visits (TEAMcare = 11.4, usual care = 12.3) and telephone encounters (TEAM-care = 10.1; usual care = 10.3 ).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow diagram.

BP = blood pressure; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; PHQ-2 = 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Intervention n = 90 Mean (SD) | Usual Care n = 91 Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c, % | 8.1 (2.1) | 8.0 (1.9) |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | 137 (18.0) | 131 (17.0) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 106.7 (35.4) | 107.5 (37.4) |

| PHQ-9 depression scorea | 14.5 (3.8) | 13.7 (3.0) |

| Diabetes (alone or with CHD), % (n) | 88.9 (80) | 83.5 (76) |

| CHD (alone or with diabetes), % (n) | 24.4 (22) | 28.6 (26) |

| Insulin use, % (n) | 45.6 (41) | 37.4 (34) |

| Oral hypoglycemic medication use, % (n) | 70.0 (63) | 57.1 (52) |

| Antihypertensive medication use, % (n) | 87.8 (79) | 83.5 (76) |

| Lipid-lowering medication use, % (n) | 75.6 (68) | 79.1 (72) |

| Antidepressant medication use, % (n) | 52.2 (47) | 56.0 (51) |

CHD = coronary heart disease; HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; PHQ-9 = 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Scored on a range from 0 to 27; higher score indicates greater depresson severity.

Patient Self-Care: Medication Adherence and Self-Monitoring

Medication adherence was high at baseline for both TEAMcare and usual care groups. Among patients refilling oral hypoglycemic agents, the mean percentage of days with available medicines was 83%. The corresponding adherence rates were 85% for antihypertensive agents, 83% for lipid-lowering drugs, and 79% for antidepressant medicines. During the intervention period, medication adherence in the TEAM-care group did not increase substantially relative to the usual care group (Table 3). At 12 months, however, the average rate of blood pressure self-monitoring was more than 3 times higher in the TEAMcare group compared with the usual care group (3.6 vs 1.1 days per week; RR = 3.20; P <.001); the average blood glucose monitoring rate was 4.9 days per week, and 3.8 days per week, respectively (RR = 1.28; P = .006).

Table 3.

Medication Adherence

| Medication Class | Intervention Mean (SD) | Usual Care Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Baseline | 12 mo | No. | Baseline | 12 mo | |

| Oral hypoglycemic | 66 | 0.83 (0.19) | 0.85 (0.17) | 58 | 0.83 (0.20) | 0.83 (0.18) |

| Antihypertensive | 73 | 0.85 (0.18) | 0.88 (0.14) | 68 | 0.86 (0.18) | 0.88 (0.16) |

| Lipid lowering | 59 | 0.82 (0.21) | 0.85 (0.17) | 57 | 0.85 (0.18) | 0.88 (0.13) |

| Antidepressant | 43 | 0.79 (0.23) | 0.85 (0.16) | 40 | 0.80 (0.19) | 0.80 (0.19) |

Note: Sample excludes new medication starts. There were no significant differences between the intervention and usual care group for all medication classes.

Pharmacotherapy Initiation and Adjustment

Among patients who had not received pharmacotherapy for a specific condition, initiation of medicines to control diabetes and coronary heart disease risk factors (blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) occurred significantly more frequently among TEAMcare patients than usual care patients. Adjusting for baseline clinical values, initiation over the year for the care management group was 3.5 times (95% CI, 2.0–6.3) that of the usual care group for antidepressant medicines and 2.7 times (95% CI, 1.1–6.2) for lipid-lowering medicines. Initiation rates of antihypertensive and insulin therapy among the care management group also tended to be higher, 1.8 (95% CI, 0.7–4.9) and 2.2 (95% CI, 0.7–6.8), respectively.

In all 5 medication categories, pharmacotherapy adjustment rates (including medication initiations) were higher among TEAMcare patients than usual care patients over the intervention year. Table 4 shows that, compared with the usual care group, the treatment adjustment rate in the care management group was 6 times higher for antidepressant medications, 3 times higher for insulin, nearly double for antihypertensive and oral hypoglycemic medications, and 1.6 times higher for lipid-lowering medications.

Table 4.

Rate of Treatment Adjustment (Number of Adjustments Over 12 Months)

| Therapeutic Class | Rate (95% CI)

|

Relative Ratea (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Usual Care | ||

| Antidepressant | 3.37 (2.92–3.89) | 0.53 (0.34–0.82) | 6.20b (3.88–9.90) |

| Insulin | 3.26 (2.43–4.36) | 1.02 (0.67–1.55) | 2.97b (1.83–4.83) |

| Oral hypoglycemic | 0.62 (0.44–0.88) | 0.34 (0.23–0.50) | 1.80c (1.07–3.01) |

| Antihypertensive | 2.33 (1.86–2.92) | 1.11 (0.81–1.51) | 1.86b (1.28–2.71) |

| Lipid lowering | 0.81 (0.64–1.03) | 0.55 (0.42–0.72) | 1.56c (1.10–2.20) |

Note: Treatment adjustment defined as (1) an increase in the number of medication classes prescribed, (2) a change in dosage of at least 1 ongoing medication class, (3) a switch to a medication in a different class, or (4) a switch to a different medication within the same class over the 12-month intervention period. Medication adjustment includes initiations and subsequent treatment changes.

Adjusted for baseline Poisson regressions with robust (Huber-White) standard errors predicting the rate of adjustments (baseline to 12 months) within each therapeutic class.

P value <.001.

P value <.05.

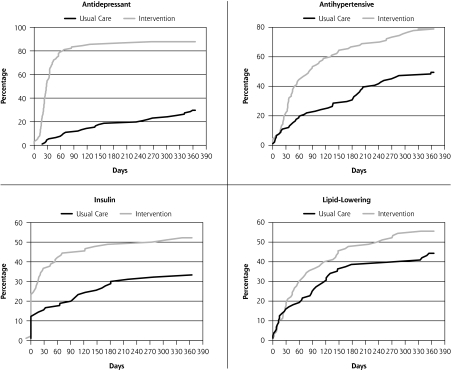

Figure 2 contrasts first adjustment between TEAMcare and usual care groups for 4 of the 5 medication classes over the year-long intervention. Most first adjustments occurred within the first 2 months for the care management patients. Compared with the usual care group, the estimated rate of first adjustment in the TEAMcare group was 10 times higher for antidepressant medications (78.9% vs 7.7%), and more than twice as high for antihypertensive agents (44.4% vs 18.7%) and insulin (41.1% vs 16.5%) in the first 2 months. At 12 months, TEAMcare patients showed significantly higher rate of first adjustment relative to usual care patients in 3 of the 5 medication classes: antidepressant agents (87.8% vs 29.7%, P <.001), antihypertensive medications (78.9% vs 49.5%, P <.001), and insulin (52.2% vs 33.0%, P = .010).

Figure 2.

Incidence of first treatment adjustment in medication classes.

DISCUSSION

TEAMcare patients increased self-monitoring of key disease parameters relative to usual care patients. Primary care physicians received notices of abnormal disease in control measures for both groups. With TEAMcare support, however, the physicians provided more timely and frequent adjustment of pharmacotherapy. Medications used in this intervention were predominantly generic, commonly prescribed first- and second-line medicines. Increases in medication dosage or addition of a pharmacologic class in the care management group occurred early in the intervention period (typically the first 30 to 60 days). Contrary to our hypothesis, no differences in medication adherence were observed. It is noteworthy that baseline medication adherence rates were high (ranging from 79% to 86%) in both usual care and TEAMcare groups.

Antidepressant treatment showed the most dramatic contrast, in that TEAMcare patients showed a sixfold increase in pharmacotherapy initiations and adjustments relative to usual care patients. A British study found that gaps in depression care were especially pronounced among elderly patients with coexisting diabetes and heart disease.46 This study identified methods for integrating mental health treatment and chronic disease care for complex patients. Treatment of depression is an important component of achieving improved outcomes among chronic disease patients with comorbid depression. Controlling depression to reduce hopelessness, helplessness, fatigue, and poor concentration may help patients collaborate more effectively with their physicians and more actively engage in self-care activities.

Prior observational studies have found that lack of physician treatment adjustment appeared more problematic than patient medication adherence among patients with poorly controlled diabetes or heart disease.17,47 This randomized trial is the first to assess modifiable patient and physician behaviors in achieving improved clinical outcomes. Increases in patient self-monitoring of blood pressure and blood glucose observed in this study support the relationship between better glycemic and blood pressure control and improved self-management.48–50

Positive results for medication management and clinical outcomes in this randomized controlled trial stand in contrast to negative results of a large demonstration project of care management.51 The redesign of primary care in this trial enabled care managers to convey treatment adjustments to the physicians on a timely basis. Key components of the TEAMcare program, based in the Chronic Care Model,37,52 include (1) collaboration among patients, care managers, and physicians in setting individualized goals and targets; (2) support for patient self-care; (3) population-based and systematic monitoring of patient progress; (4) timely pharmacotherapy adjustment to achieve treatment goals (treat-to-target); and (5) multidisciplinary consultants for case review with nurse care managers to ensure accountability in achieving optimal outcomes.

In addition to patient self-monitoring and treatment adjustments by physicians, it is likely that other core components of the intervention, such as the presence of a care manager to systematically monitor patient progress and support self-care activities and regular multidisciplinary case review, all contributed to better disease control. Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression, however, has been found in highly diverse care settings, with robust effect sizes among patients with little resources and lower medication adherence.53,54 Availability of electronic health records may curtail adoption by smaller practices. Generalizability of this study may be limited by focusing on highly complex patients with multiple uncontrolled chronic illnesses; these patients represent a small fraction of primary care patients at high risk for poor outcomes and generate much of the health care costs. Even so, the principles of systematic chronic illness care, treat-to-target, and integration of treatment for mental and physical illnesses can be applied to most patients with chronic illnesses, regardless of whether they have depression or need intensive care management. Major quality improvement initiatives for diabetes and hypertension were implemented across the health plan during the study period and could have accounted for the relatively high medication adherence rates observed among usual care patients. For this reason, experimental differences observed between intervention and usual care patients may represent conservative estimates. Treatment adjustment by physicians, such as adding new medicines or dosage adjustments, may potentially lower adherence in the intervention group. The medication adherence measure used was derived from pharmacy refill data, which may be less sensitive in detecting changes in how patients take medicines (with more daily regularity). This measure was calculated as an average per therapeutic class per disease, because hyperglycemia, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia are often treated with multiple medications.

Results of this trial suggest that improving specific patient and clinician behaviors (close monitoring of disease control parameters and timely treatment adjustments to achieve individualized goals) can improve disease control and quality of life among patients with multiple conditions and complex health care needs. In view of the current state of fragmented care of individual patients,5 a TEAMcare program, through which primary and specialty care services are integrated and coordinated to provide patient-centered services, offers a sorely needed framework and methods to improve outcomes of patients with chronic illness and coexisting mood disorders within the primary care medical home setting.55

Acknowledgment

We thank the patients, primary care physicians, consultants, and Group Health leaders for their participation and support. Thanks also to the Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr Lin served on an advisory board for Physicians Postgraduate Press, and received honoraria for lectures and manuscripts from Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement, Prescott Medical, and HealthSTAR Communications (Eli Lilly), travel fees from the World Psychiatry Association, and a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Dr Von Korff has a grant pending from Johnson & Johnson. Dr Ciechanowski served on the editorial boards of Diabetic Living and Diabetes Forecast, owns and has a patent for Samepage (samepagehealth.com), received lecture fees from Rewarding Health (rewardinghealth.com), and received travel feeds from Roche Diagnostics. Ms McGregor received travel and lecture fees from Group Health Cooperative. Dr Katon received support as an advisor to Wyeth and Eli Lilly and lectures fees from Wyeth, Eli Lilly, Forest Laboratories, and Pfizer. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding support: National Institute of Mental Health grants (MH041739, and MH069741).

Previous presentation: Presented at National Association of Primary Care Research Group, Seattle, Washington, November 13–17, 2010.

References

- 1.Schneider KM, O’Donnell BE, Dean D. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ Medicare population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA. 2004;291(3):335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Lemke KW, Bernhardt T, Foldes SS, Forrest CB, Weiner JP. Comorbidity: implications for the importance of primary care in ‘case’ management. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):8–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Care Management of Patients With Complex Health Care Needs, The Synthesis Project. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health & Human Services Multiple Chronic Conditions: A Strategic Framework. Washington, DC; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh AK, Barton MB. The challenge of multiple comorbidity for the US health care system. JAMA. 2010;303(13):1303–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Partnership for solutions: better lives for people with chronic conditions. Grant Results Reports. 2006. http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org

- 8.Stange KC. Is ‘clinical inertia’ blaming without understanding? Are competing demands excuses? Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):371–374 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parchman ML, Pugh JA, Romero RL, Bowers KW. Competing demands or clinical inertia: the case of elevated glycosylated hemoglobin. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):196–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron RJ. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1632–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner BJ, Hollenbeak CS, Weiner M, Ten Have T, Tang SS. Effect of unrelated comorbid conditions on hypertension management. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(8):578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr EA, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Klamerus ML, Subramanian U, Hogan MM, Hofer TP. The role of clinical uncertainty in treatment decisions for diabetic patients with uncontrolled blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):717–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Self-monitoring and other non-pharmacological interventions to improve the management of hypertension in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(581):e476–e488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin S, Schneider B, Heinemann L, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes and long-term outcome: an epidemiological cohort study. Diabetologia. 2006;49(2):271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Karter AJ, et al. Why don’t diabetes patients achieve recommended risk factor targets? Poor adherence versus lack of treatment intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(5):588–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin EH, Rutter CM, Katon W, et al. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):264–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ismail K, Winkley K, Stahl D, Chalder T, Edmonds M. A cohort study of people with diabetes and their first foot ulcer: the role of depression on mortality. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1473–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2668–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Korff M, Katon W, Lin EH, et al. Potentially modifiable factors associated with disability among people with diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(2):233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EHB, et al. Diabetes complications and depression as predictors of health service costs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(5):344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludman EJ, Katon W, Russo J, et al. Depression and diabetes symptom burden. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(6):430–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Hirsch IB. The relationship of depressive symptoms to symptom reporting, self-care and glucose control in diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(4):246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2751–2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2002;40(9):794–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin EHB, Katon WVKM, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2154–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1218–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Bruggen R, Gorter K, Stolk RP, Zuithoff P, Klungel OH, Rutten GE. Refill adherence and polypharmacy among patients with type 2 diabetes in general practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009; 18(11):983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27): 2611–2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. Switzerland: S. Karger AG; 1974:79–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Von Korff M, Katon WJ, Lin EHB, et al. Functional outcomes of multi-condition collaborative care and successful ageing: results of randomized trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d6612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katon W, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Integrating depression and chronic disease care among patients with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease: the design of the TEAMcare study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(4):312–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273(13):1026–1031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. ; IMPACT Investigators Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22): 2836–2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12): 1097–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J; Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators The Treat-to-Target Trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3080–3086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steiner JF, Koepsell TD, Fihn SD, Inui TS. A general method of compliance assessment using centralized pharmacy records. Description and validation. Med Care. 1988;26(8):814–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):565–574; discussion 575–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, et al. Diabetes and poor disease control: is comorbid depression associated with poor medication adherence or lack of treatment intensification? Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9): 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalbfleish J, Prentice R. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, et al. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ. 2009;338:b750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddox TM, Ross C, Tavel HM, et al. Blood pressure trajectories and associations with treatment intensification, medication adherence, and outcomes among newly diagnosed coronary artery disease patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(4):347–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. A structured self-monitoring of blood glucose approach in type 2 diabetes encourages more frequent, intensive, and effective physician interventions: results from the STeP study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(8):797–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karter AJ, Ackerson LM, Darbinian JA, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels and glycemic control: the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Diabetes registry. Am J Med. 2001;111(1):1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McManus RJ, Mant J, Bray EP, et al. Telemonitoring and self-management in the control of hypertension (TASMINH2): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):163–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009; 301(6):603–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28 (1):75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Areán PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, et al. ; IMPACT Investigators Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Med Care. 2005;43(4):381–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaén C. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: lessons from the national demonstration project. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):439–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]