Abstract

Two recent metaanalyses of genome-wide association studies conducted by the CHARGE and SpiroMeta consortia identified novel loci yielding evidence of association at or near genome-wide significance (GWS) with FEV1 and FEV1/FVC. We hypothesized that a subset of these markers would also be associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) susceptibility. Thirty-two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in or near 17 genes in 11 previously identified GWS spirometric genomic regions were tested for association with COPD status in four COPD case-control study samples (NETT/NAS, the Norway case-control study, ECLIPSE, and the first 1,000 subjects in COPDGene; total sample size, 3,456 cases and 1,906 controls). In addition to testing the 32 spirometric GWS SNPs, we tested a dense panel of imputed HapMap2 SNP markers from the 17 genes located near the 32 GWS SNPs and in a set of 21 well studied COPD candidate genes. Of the previously identified GWS spirometric genomic regions, three loci harbored SNPs associated with COPD susceptibility at a 5% false discovery rate: the 4q24 locus including FLJ20184/INTS12/GSTCD/NPNT, the 6p21 locus including AGER and PPT2, and the 5q33 locus including ADAM19. In conclusion, markers previously associated at or near GWS with spirometric measures were tested for association with COPD status in data from four COPD case-control studies, and three loci showed evidence of association with COPD susceptibility at a 5% false discovery rate.

Clinical Relevance

This study examines hits at or near genome-wide significance from two large genome-wide association studies of spirometric phenotypes and tests for their association with COPD status in four large COPD case-control studies. This study identifies three genetic loci that are associated with COPD susceptibility.

Two recent genome-wide association (GWA) metaanalysis studies conducted by the CHARGE and SpiroMeta consortia identified a number of novel loci associated at or near genome-wide significance (GWS) with two spirometric measures of pulmonary function, FEV1/FVC and FEV1 (1, 2). Because FEV1/FVC and FEV1 are used to define the presence and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), there is a relatively high likelihood that genomic loci associated with these measures are also associated with COPD susceptibility.

There has been notable overlap between the results of previous genome-wide association studies for spirometric measures and COPD status. Of the three loci that have been associated with COPD through genome-wide association studies, two have been associated with FEV1 or FEV1/FVC. Before the publication of the CHARGE and SpiroMeta studies, the largest GWA study of spirometric measures (3) and a COPD GWA study (4) had identified a common region for association with their respective phenotypes, an area on 4q31 near the HHIP gene. The association at this locus was confirmed by a joint metaanalysis of the top hits from the CHARGE and SpiroMeta samples. In addition, the FAM13A locus was strongly associated with FEV1 in the CHARGE study and with COPD affection status in a collaborative COPD case-control study (5).

Given the overlap in results from previously performed spirometry and COPD GWA studies, the identification of novel loci associated with FEV1 and FEV1/FVC raises the question of whether these loci are also associated with COPD. We hypothesized that 32 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 17 genes (11 novel loci) identified from the CHARGE and SpiroMeta studies were likely to be associated with COPD susceptibility. We tested the top hits from the CHARGE and SpiroMeta studies for association with COPD susceptibility using GWA data from four COPD case-control studies. In addition to testing the 32 GWS SNPs, we performed extended association testing using dense, imputed genotype data spanning 50 kb up and downstream of the 17 genomic regions containing the GWS SNPs. For comparison, we performed similar association testing using imputed genotype data in a number of well studied genes in COPD from the candidate gene era.

Materials and Methods

Study Samples

Genome-wide genotyping data from individuals of European ancestry was used from four case-control studies: (1) the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study (6), (2) a case-control cohort from Norway (7), (3) the first 1,000 subjects from the COPDGene Study (www.copdgene.org), and (4) cases from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) (8) and controls from the Normative Aging Study (NAS) (9). Information regarding inclusion criteria for these study samples has been published previously (5).

Genotyping Quality Control, Assessment of Population Stratification, and Imputation

Details regarding genotyping techniques, quality control, and imputation are presented in the online supplement.

Selection of Candidate Genes and SNPs

Two sets of genes were included in our analysis: 17 genes harboring SNPs from 11 loci with association P values at or near GWS in the CHARGE or SpiroMeta GWA metaanalyses (“spirometric GWS genes”) and a set of 21 genes that have been previously studied for association with COPD (i.e., COPD “candidate genes”). The 21 COPD candidate genes were selected by literature review and the authors' perceived likelihood that specific genes were likely to be associated with COPD (10). “Top hit” loci from the spirometric GWA metaanalyses (“spirometric GWS SNPs”) were extracted from the Results tables presented in the primary publications (1, 2).

Statistical Analysis

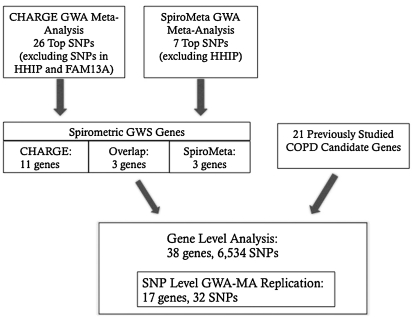

We performed SNP-level “replication” (not exact replication because we tested for association with a related but different phenotype) for 32 spirometric GWS SNPs. To identify other potentially associated sites in 17 genes near these 32 SNPs and in 21 additional COPD candidate genes, we performed a gene-based analysis in which we performed single SNP association testing using a dense panel of 6,534 genotyped and imputed SNPs spanning 50 kb upstream and downstream from each of the 38 genes (as defined by transcription start and end sites) (UCSC Genome browser and Galaxy, using the NCBI reference human genome build 36.1). We excluded HHIP and FAM13A from the spirometry GWS genes because COPD association results for SNPs in both genes in our study samples have been previously reported (4, 5). SNP imputation was based on HapMap CEU reference samples using MaCH 1.0 (11). The 32 GWA metaanalysis replication SNPs are a subset of the 6,534 SNPs from the gene-based analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of association tests for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) susceptibility. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified from the CHARGE and SpiroMeta spirometric genome-wide association (GWA) metaanalyses and a set of previously studied COPD candidate genes. Two association tests were conducted: (1) a SNP level “replication” for 32 SNPs extracted from the CHARGE and SpiroMeta publications and (2) a gene-based extended association analysis for the 17 genes located near the 32 SNPs above in addition to 21 other COPD candidate genes. The 32 SNPs are a subset of the 6,534 genotyped and imputed fine mapping SNPs. Of these 32 SNPs, 25 are from CHARGE, 6 are from SpiroMeta, and 1 was reported in both studies. GWA-MA = genome-wide association metaanalysis; GWS = genome-wide significance.

We performed genetic association testing using logistic regression with binary COPD affection status as the dependent variable and age, pack-years of cigarette exposure, and principal components of genetic ancestry as the independent variables. We excluded SNPs with a minor allele frequency less than 1% before analysis. Association analysis was performed in each of the four study samples, and results were combined using the metaanalysis option in PLINK (12, 13).

We used two separate approaches to control for multiple statistical testing: the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR) as implemented in the R function p.adjust (14) and a permutation-based procedure. A full description of these methods can be found in the online supplement.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the cohorts are shown in Table 1. The case-control ratio was roughly 1:1 in each of the study samples, with the exception of the ECLIPSE cohort, which included more cases than controls by design. The age and gender distributions were roughly balanced in each cohort, with the exception of NAS, which consisted entirely of male subjects. Cigarette smoke exposure was systematically higher in cases, as is often observed in COPD case-control studies (10). The levels of FEV1 by case/control status were similar across studies, with the exception of NETT, in which study subjects had, on average, more severe airflow obstruction. In the other three case groups, most cases had moderate to severe airflow obstruction (i.e., GOLD Stage II–III COPD).

TABLE 1.

STUDY SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

| Norway (GenKOLs) |

ECLIPSE |

COPD Gene |

||||||

| NETT Cases | NAS Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | |

| N | 373 | 435 | 863 | 808 | 1764 | 178 | 499 | 501 |

| Age | 67 (6)* | 70 (7) | 65 (10) | 56 (10) | 64 (7) | 57 (9) | 65 (8) | 60 (9) |

| Sex, n (% male) | 238 (64) | 435 (100) | 518 (60) | 404 (50) | 1,182 (67) | 103 (58) | 247 (50) | 251 (50) |

| Pack-years, median (IQR) | 61 (44–84) | 33 (20–53) | 28 (20–41) | 17 (9–27) | 45 (32–60) | 28 (18–39) | 48 (38–72) | 36 (23–48) |

| FEV1, % predicted | 28 (7) | 100 (13) | 51 (17) | 95 (9) | 47 (16) | 108 (14) | 49 (18) | 98 (11) |

Definition of abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range.

Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. The following numbers of subjects were removed before analysis as outliers along a principal component of genetic ancestry: NETT (1 case, 6 control subjects), GenKOLs (10 cases, 3 control subjects), ECLIPSE (28 cases, 2 control subjects), and COPDGene (3 cases, 3 control subjects).

A schematic overview of the SNP-level replication and gene-based extended association analysis is shown in Figure 1. The results of the SNP-level replication analysis, in which the 32 SNPs at or near GWS in the spirometric GWA metaanalyses were tested for association with COPD susceptibility, are shown in Table 2. These 32 SNPs represent 11 independent loci, three of which contained SNPs associated with COPD susceptibility at an FDR < 5% (Table 2). In the spirometric GWA metaanalyses, the 4q24 locus was associated with FEV1, and the 6p21 and 5q33 loci were associated with FEV1/FVC. For the SNPs associated with COPD susceptibility at an FDR < 5%, the direction of the odds ratio was consistent with the effect observed in the spirometric GWA studies (i.e., alleles that were associated with lower levels of FEV1 or FEV1/FVC were associated with a higher risk of COPD). Individual cohort association results for SNPs in these three loci are available in Table E1 in the online supplement. In addition to controlling the FDR by the Benjamini-Hochberg method, we performed an alternative adjustment for multiple comparisons using a permutation-based approach. After this adjustment, there was borderline evidence for an association with rs11727189 in the 4q24 locus (P = 0.067). The strongest associations in the 6p21 and 5q33 loci had permutation-adjusted P values of 0.167 and 0.214, respectively, when compared against the empiric distribution of the top-ranked SNP from each permutation.

TABLE 2.

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE GENETIC ASSOCIATION RESULTS FOR TOP ASSOCIATIONS FROM PULMONARY FUNCTION GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION METAANALYSES

| SNP | Gene | Locus | PF-GWA Phenotype* | Reference | Ref. Allele† | Frequency‡ | PF beta§ | COPD OR¶ | P Value# |

| rs11727189 | INTS12 | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.06–0.07 | + | 0.73 | 0.004†† |

| rs10516526 | GSTCD | 4q24 | FEV1 | (2) | G | 0.06–0.08 | + | 0.76 | 0.007†† |

| rs17036090 | INTS12 | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.92–0.94 | — | 1.32 | 0.007†† |

| rs11097901 | GSTCD | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.06–0.08 | + | 0.77 | 0.008†† |

| rs17036341 | NPNT | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | C | 0.92–0.94 | — | 1.29 | 0.01†† |

| rs17035960 | FLJ20184 | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.06–0.07 | + | 0.77 | 0.01†† |

| rs11728716 | GSTCD | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | A | 0.06–0.08 | + | 0.78 | 0.01†† |

| rs17036052 | FLJ20184 | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.05–0.06 | + | 0.76 | 0.02 |

| rs17331332 | NPNT | 4q24 | FEV1 | (1) | A | 0.08–0.10 | + | 0.80 | 0.03 |

| rs1052443 | NT5DC1 | 6q22 | FEV1 | (1) | A | 0.63–0.64 | — | 1.06 | 0.25 |

| rs3995090 | HTR4 | 5q31–33 | FEV1 | (2) | C | 0.38–0.42 | + | 0.95 | 0.28 |

| rs3749893 | TSPYL4 | 6q22 | FEV1 | (1) | A | 0.35–0.37 | + | 0.95 | 0.35 |

| rs6889822 | HTR4 | 5q31–33 | FEV1 | (2) | G | 0.37–0.41 | + | 0.95 | 0.37 |

| rs7710510 | ADCY2 | 5p15 | FEV1 | (1) | T | 0.19–0.20 | — | 0.98 | 0.78 |

| rs2571445 | TNS1 | 2q35–36 | FEV1 | (2) | G | 0.60–0.61 | + | 1.00 | 0.95 |

| rs6555465 | ADCY2 | 5p15 | FEV1 | (1) | A | 0.18–0.19 | + | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| rs2070600 | AGER | 6p21 | FEV1/FVC | (1, 2) | T | 0.04–0.06 | + | 0.73 | 0.01†† |

| rs2277027 | ADAM19 | 5q33 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.64–0.67 | + | 0.88 | 0.01†† |

| rs1422795 | ADAM19 | 5q33 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.64–0.67 | + | 0.88 | 0.01†† |

| rs10947233 | PPT2 | 6p21 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.04–0.05 | + | 0.74 | 0.02 |

| rs10498230 | PID1 | 2q36 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.06–0.07 | + | 0.79 | 0.02 |

| rs1435867 | PID1 | 2q36 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.93–0.94 | — | 1.26 | 0.02 |

| rs12899618 | THSD4 | 15q23 | FEV1/FVC | (2) | G | 0.84–0.85 | + | 0.92 | 0.23 |

| rs11168048 | HTR4 | 5q31–33 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.57–0.61 | — | 1.05 | 0.31 |

| rs7735184 | HTR4 | 5q31–33 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.38–0.42 | + | 0.95 | 0.33 |

| rs2395730 | DAAM2 | 6p21 | FEV1/FVC | (2) | C | 0.42–0.44 | + | 1.04 | 0.45 |

| rs6937121 | GPR126 | 6q24 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | T | 0.70–0.74 | — | 1.04 | 0.46 |

| rs7776375 | GPR126 | 6q24 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.71–0.76 | — | 1.03 | 0.57 |

| rs16909898 | PTCH1 | 9q22 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.89–0.91 | + | 0.97 | 0.74 |

| rs3817928 | GPR126 | 6q24 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.78–0.82 | — | 0.98 | 0.76 |

| rs11155242 | GPR126 | 6q24 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.79–0.83 | — | 0.98 | 0.77 |

| rs10512249 | PTCH1 | 9q22 | FEV1/FVC | (1) | A | 0.09–0.12 | — | 1.02 | 0.78 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR = odds ratio; PF-GWA = pulmonary function/spirometry genome-wide association meta-analysis; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism;

Phenotype associated with SNP at genome-wide significance in spirometry genome-wide association (GWA) metaanalysis.

Reference allele for spirometry GWA betas and COPD genetic associations.

Range of frequencies for reference allele in the four COPD study samples.

Direction of beta-coefficient for SNP effect in spirometry GWA metaanalyses.

Combined odds ratio from COPD genetic association analysis in the four study samples.

Unadjusted P value for association with COPD status.

Significant at false discovery rate < 5% by Benjamini-Hochberg.

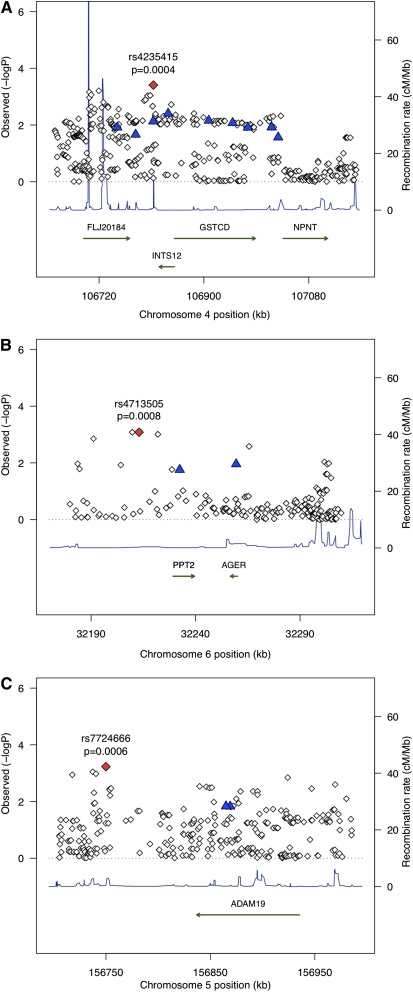

We performed gene-based extended association testing (single SNP tests for all HapMap2 SNPs within 50 kb upstream or downstream of the gene) using imputed and directly genotyped data from the spirometry GWS genes and the set of COPD candidate genes. The relationships between the 32 spirometric GWS SNPs and the top hits in these genes from the gene-based analysis are shown in Table 3. For the three spirometric GWS loci associated with COPD at an FDR < 5%, the degree of linkage disequilibrium between the spirometric GWS SNP and the top SNPs in the gene-based analysis varied widely (r2 = 0.07–0.71), suggesting that for at least some of these loci the top gene-based extended association result may represent an independent signal. Localization plots for these three loci are shown in Figure 2.

TABLE 3.

GENOMIC DISTANCE AND LINKAGE DISEQUILIBRIUM BETWEEN TOP HITS FROM SPIROMETRIC GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION METAANALYSES AND TOP HITS FROM GENE-BASED ASSOCIATION ANALYSIS*

| Gene | PF-GWA Hit | COPD-FM Hit | Distance (bp) | R2† |

| INTS12 | rs11727189 | rs4235415 | 25,290 | 0.53 |

| GSTCD | rs10516526 | rs4235415 | 95,054 | 0.62 |

| INTS12 | rs17036090 | rs4235415 | 276 | 0.71 |

| GSTCD | rs11097901 | rs4235415 | 136,083 | 0.62 |

| NPNT | rs17036341 | rs11933466 | 15,903 | 0.30 |

| FLJ20184 | rs17035960 | rs4235415 | 62,004 | 0.71 |

| GSTCD | rs11728716 | rs4235415 | 162,146 | 0.62 |

| FLJ20184 | rs17036052 | rs4235415 | 30,471 | 0.43 |

| NPNT | rs17331332 | rs11933466 | 4,625 | 0.22 |

| NT5DC1 | rs1052443 | rs1931898 | 133,729 | 0.02 |

| HTR4 | rs3995090 | rs17706683 | 78,440 | 0.00 |

| TSPYL4 | rs3749893 | rs4326261 | 42,606 | 0.01 |

| HTR4 | rs6889822 | rs17706683 | 77,548 | 0.00 |

| ADCY2 | rs7710510 | rs11134242 | 136,726 | 0.02 |

| TNS1 | rs2571445 | rs10204348 | 51,799 | 0.00 |

| ADCY2 | rs6555465 | rs11134242 | 129,398 | 0.02 |

| AGER | rs2070600 | rs9267803 | 49,681 | 0.21 |

| ADAM19 | rs2277027 | rs7724666 | 115,000 | 0.07 |

| ADAM19 | rs1422795 | rs7724666 | 118,988 | 0.07 |

| PPT2 | rs10947233 | rs9267803 | 22,662 | 0.14 |

| PID1 | rs10498230 | rs7580152 | 390,245 | 0.02 |

| PID1 | rs1435867 | rs7580152 | 381,819 | 0.02 |

| THSD4 | rs12899618 | rs4316710 | 156,900 | 0.00 |

| HTR4 | rs11168048 | rs17706683 | 81,902 | 0.00 |

| HTR4 | rs7735184 | rs17706683 | 2,039 | 0.00 |

| DAAM2 | rs2395730 | rs12206691 | 36,325 | 0.02 |

| GPR126 | rs6937121 | rs9389983 | 73,389 | 0.09 |

| GPR126 | rs7776375 | rs9389983 | 143,320 | 0.09 |

| PTCH1 | rs16909898 | rs357527 | 25,301 | 0.29 |

| GPR126 | rs3817928 | rs9389983 | 116,772 | 0.11 |

| GPR126 | rs11155242 | rs9389983 | 57805 | 0.11 |

| PTCH1 | rs10512249 | rs357527 | 25301 | 0.29 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD-FM Hit = single-nucleotide polymorphism with strongest association signal for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility; PF-GWA Hit = locus attaining genome-wide significance in pulmonary function (spirometric) genome-wide association studies.

Distance based on UCSC hg 18.

R2 in HapMap CEU samples.

Figure 2.

Localization plots showing the results of association testing for COPD susceptibility loci at 4q24 (A), 6p21 (B), and 5q33 (C). The red diamond marks the most strongly associated SNP in our study, and the blue triangles represent SNPs identified in pulmonary function GWA metaanalyses. Analyzed genes are depicted with green arrows, and recombination rates based on HapMap data are represented as blue triangles.

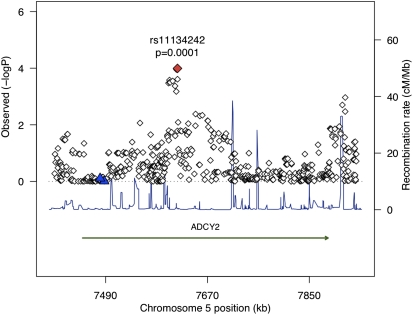

For the genes analyzed in the gene-based extended association analysis (17 spirometry GWA-identified genes and 21 COPD candidate genes), the SNPs with the strongest association with COPD are shown in Table 4 (cohort-specific results are presented in Table E2). The top 10 genes are spirometric GWS genes, and the most strongly associated SNP in the gene-based extended association analysis was rs11134242 in ADCY2 (unadjusted P = 0.0001). The localization plot for this locus is shown in Figure 3. A number of candidate genes harbored SNPs with low P values, but, after adjustment for multiple testing, no SNPs were identified at FDR < 5%. The three most strongly associated SNPs in candidate genes were in loci including MMP1/MMP12, TNF, and SFTPB (unadjusted P values ≤ 0.005) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

TOP HITS FROM GENE-BASED ASSOCIATION ANALYSIS FOR SPIROMETRIC GENOME-WIDE SIGNIFICANCE GENES AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE CANDIDATE GENES

| SNP* | Genes | Ref. Allele† | Frequency‡ | OR | P Value§ |

| rs11134242 | ADCY2 | G | 0.59–0.63 | 1.23 | 0.0001 |

| rs10204348 | TNS1 | G | 0.36–0.41 | 0.83 | 0.0002 |

| rs4316710 | THSD4 | C | 0.81–0.83 | 0.79 | 0.0003 |

| rs4235415 | FLJ20184/GSTCD/INTS12 | G | 0.13–0.17 | 0.77 | 0.0004 |

| rs7724666 | ADAM19 | C | 0.87–0.89 | 1.32 | 0.0006 |

| rs4713505 | AGER/PPT2 | T | 0.26–0.3 | 0.83 | 0.0008 |

| rs17706683 | HTR4 | A | 0.05–0.06 | 0.55 | 0.0009 |

| rs645419 | MMP1/MMP12 | G | 0.46–0.48 | 0.85 | 0.001 |

| rs12206691 | DAAM2 | A | 0.98–0.98 | 1.79 | 0.004 |

| rs2736172 | TNF | C | 0.61–0.65 | 1.16 | 0.004 |

| rs11933466 | NPNT | A | 0.2–0.25 | 0.84 | 0.005 |

| rs17736515 | SFTPB | A | 0.05–0.07 | 1.38 | 0.005 |

| rs3917386 | IL1B | C | 0.06–0.06 | 1.42 | 0.008 |

| rs7580152 | PID1 | A | 0.14–0.15 | 1.21 | 0.009 |

| rs8176707 | ABO | G | 0.88–0.91 | 0.80 | 0.01 |

| rs2853209 | ADAM33 | A | 0.45–0.5 | 1.15 | 0.01 |

| rs3744787 | TIMP2 | G | 0.12–0.15 | 1.20 | 0.01 |

| rs9389983 | GPR126 | T | 0.48–0.54 | 0.89 | 0.02 |

| rs17108817 | ADRB2 | C | 0.44–0.5 | 0.88 | 0.02 |

| rs17622933 | SOD3 | A | 0.29–0.3 | 1.14 | 0.02 |

| rs357527 | PTCH1 | A | 0.07–0.09 | 1.24 | 0.02 |

| rs16865545 | SERPINE2 | A | 0.83–0.85 | 0.86 | 0.03 |

| rs3738037 | EPHX1 | A | 0.09–0.1 | 1.22 | 0.03 |

| rs1554286 | IL10 | A | 0.19–0.21 | 1.16 | 0.03 |

| rs6094238 | MMP9 | C | 0.75–0.77 | 1.13 | 0.04 |

| rs1931898 | NT5DC1 | C | 0.95–0.96 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

| rs6258 | TP53 | C | 0.97–0.98 | 1.30 | 0.08 |

| rs743813 | HMOX1 | C | 0.45–0.48 | 1.09 | 0.11 |

| rs12745189 | GSTM1 | T | 0.45–0.47 | 0.92 | 0.12 |

| rs20541 | IL13 | A | 0.19–0.21 | 0.91 | 0.13 |

| rs1800472 | TGFB1 | A | 0.01–0.03 | 1.46 | 0.13 |

| rs9291163 | GC | T | 0.4–0.42 | 1.06 | 0.23 |

| rs7744809 | TSPYL4 | A | 0.37–0.37 | 0.94 | 0.24 |

| rs676653 | GSTP1 | A | 0.97–0.98 | 1.25 | 0.33 |

Definition of abbreviations: OR = odds ratio; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

SNPs are the top ranking SNPs in each gene by P value. Some genic intervals overlap, resulting in the same top ranking SNP for different intervals.

Allele of reference for calculation of odds ratio.

Range of frequencies of the reference allele in the four study samples.

Unadjusted P value for association with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 3.

Localization plot demonstrating the strongest association from the gene-based extended association analysis, rs11134242 in the spirometric GWA-identified gene ADCY2. The red diamond marks the most strongly associated SNP in our study, and the blue triangles represent SNPs identified in spirometric GWA metaanalyses. These results suggest that the signal observed in our study may arise from a locus distinct from that observed in the study by Hancock and colleagues.

Discussion

Using genome-wide SNP genotype data and imputed genotype data, we have explored whether genomic loci at or near GWS for spirometric phenotypes are associated with susceptibility to COPD in multiple independent study samples, and we identified significant (FDR < 5%) associations with COPD susceptibility at three loci. Our findings suggest that genetic loci that are important for spirometric phenotypes are also good candidates for association with COPD susceptibility. Furthermore, when these GWA-identified genes were compared against an a priori defined set of previously studied “candidate” genes, the strongest associations were in the GWA-identified genes.

Of the 11 novel loci identified by GWA metaanalysis of the CHARGE and SpiroMeta consortia, three loci (4q24, 6p21, and 5q33) contained SNPs that were associated with COPD susceptibility at an FDR of 5%. The odds ratios for SNPs with an FDR < 5% were approximately 1.30, consistent with the effect sizes observed in previous COPD GWA studies (4, 5).

Genes in the 4q24 region are responsible for a range of functions, including 3′ end processing of small nuclear RNAs (INTS12) (15), detoxification of exogenous compounds (GSTCD) (16), and extracellular interactions critical for organ development (17) and cellular differentiation (NPNT) (18). Each of these three genes is expressed in lung or tracheal tissue (2, 17, 19). Little is known about the function of FLJ20184, though it has been previously identified in a GWA study of smoking cessation (20). The top hit from our gene-based analysis of this region lies within a predicted gene, FLJ43963 (19). The 6p21 locus lies in the MHC region and is of particular interest for pulmonary disease because the top spirometric GWA hit in AGER, rs2070600, is a nonsynonymous SNP likely to have functional significance (21). AGER is highly expressed in human lung tissue and has been implicated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (22, 23). The 5q33 locus contains ADAM19, a member of the ADAM family of genes, which is characterized by disintegrin and metalloproteinase domains.

Although each of these three loci was associated with COPD at an FDR < 5%, when we performed a separate, permutation-based multiple testing adjustment, the lowest adjusted P value was 0.067. Although permutation-based procedures offer many advantages when controlling for multiple testing under dependency, our procedure compared all hits with the empiric distribution of the top-ranked SNP from each simulation, which may be considered a conservative approach for all but the top-ranked observed association. Given these findings, we feel that the observed association between these loci and COPD susceptibility should be considered as a suggestive association until further confirmation is possible.

The strongest association signal from our gene-based extended association analysis of spirometric GWS genes and COPD candidate genes was rs11134242 in ADCY2. The ADCY2 gene product is a membrane-associated protein whose role in G-protein coupled receptor signaling has been supported by multiple lines of functional data (24). Although this locus did not retain nominal significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons, Uhl and colleagues have suggested, in a GWA analysis of smoking cessation, that SNPs within this gene are associated with smoking cessation (20).

The interpretation of these results fundamentally relates to the nature of the relationship between spirometric measures in healthy and COPD populations and to the underlying biology of the healthy and diseased lung. In normal lung development, lung capacity increases through childhood and adolescence, peaking in the second or third decade of life (25). Early measures of lung function are highly predictive of subsequent measures (i.e., lung function “tracks” as children and adolescents grow and develop) (26). After the third decade of life, all individuals experience a progressive loss of lung function (25). Individuals who smoke cigarettes typically have a more rapid loss of lung function (27), and a subset of individuals develop airflow obstruction consistent with the presence of COPD. Thus, for lung function measures and COPD status, the maximal lung volume attained during growth and development and the rate of subsequent lung function decline are critical factors. Thus, one would expect that, for spirometric measures and COPD, genes related to normal lung growth and development, detoxification of inhaled compounds, and regulation of the inflammatory response to the environment might play an important role and that the relative importance of these processes may differ between healthy individuals and those with COPD.

Our study is the first to report the association between the recently reported novel pulmonary function loci and COPD susceptibility. The availability of questionnaire data regarding cigarette smoke exposure allowed us to account for this important environmental exposure in our genetic association analyses, although we acknowledge that such adjustments for smoking are imprecise. We were able to adjust for population stratification and impute a panel of densely spaced SNP markers for extended association testing of the genomic regions of interest.

Our study has a number of limitations. Although our sample size equals or exceeds that of any previous COPD GWA study, it is small compared with the sample sizes of the spirometric GWA metaanalyses, and our dichotomous phenotype affords less power than a continuous phenotype, such as FEV1. Thus, failure to demonstrate significant associations between spirometric GWA-identified loci and COPD may reflect a lack of power rather than an absence of association. The imbalance between cases and control subjects in the ECLIPSE study also adversely affects power. Despite these potential effects on statistical power, the number of tests performed in our analysis was orders of magnitude smaller than in the spirometric GWA metaanalyses. Our study also suffers from a degree of heterogeneity in the severity of COPD between the four study samples. Our study samples included only subjects of European descent, so our findings cannot be generalized to populations of non-European ancestry. Finally, due to the different nature of COPD case-control cohorts and those used for studies of spirometric measures in the general population, there are differences in characteristics between our samples and those included in the spirometric GWA metaanalyses, although the fundamental goal of our project was to assess the generalizability of spirometric GWA findings to a different target population.

In summary, targeted association testing of spirometric GWA-implicated loci in data from four COPD GWA study samples identified three loci associated with COPD susceptibility at an FDR of 5%. Our findings also suggest that genomic loci identified from pulmonary function GWA studies are good candidates for association with COPD susceptibility.

Acknowledgments

COPDGene Study Group: Ann Arbor, VA: Jeffrey Curtis, M.D. (PI); Ella Kazerooni, M.D. (RAD). Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX: Nicola Hanania, M.D., M.S. (PI); Philip Alapat, M.D.; Venkata Bandi, M.D.; Kalpalatha Guntupalli, M.D.; Elizabeth Guy, M.D.; Antara Mallampalli, M.D.; Charles Trinh, M.D. (RAD); Mustafa Atik, M.D. Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA: Dawn DeMeo, M.D., M.P.H. (Co-PI); Craig Hersh, M.D., M.P.H. (Co-PI); George Washko, M.D.; Francine Jacobson, M.D., M.P.H. (RAD). Columbia University, New York, NY: R. Graham Barr, M.D., Dr.P.H. (PI); Byron Thomashow, M.D.; John Austin, M.D. (RAD). Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC: Neil MacIntyre, Jr., M.D. (PI); Lacey Washington, M.D. (RAD); H. Page McAdams, M.D. (RAD). Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA: Richard Rosiello, M.D. (PI); Timothy Bresnahan, M.D. (RAD). Health Partners Research Foundation, Minneapolis, MN: Charlene McEvoy, M.D., M.P.H. (PI); Joseph Tashjian, M.D. (RAD). Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Robert Wise, M.D. (PI); Nadia Hansel, M.D., M.P.H.; Robert Brown, M.D. (RAD); Gregory Diette, M.D. Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA: Richard Casaburi, M.D. (PI); Janos Porszasz, M.D., Ph.D.; Hans Fischer, M.D., Ph.D. (RAD); Matt Budoff, M.D. Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX: Amir Sharafkhaneh, M.D. (PI); Charles Trinh, M.D. (RAD); Hirani Kamal, M.D.; Roham Darvishi, M.D. Minneapolis, VA: Dennis Niewoehner, M.D. (PI); Tadashi Allen, M.D. (RAD); Quentin Anderson, M.D. (RAD); Kathryn Rice, M.D. Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA: Marilyn Foreman, M.D., M.S. (PI); Gloria Westney, M.D., M.S.; Eugene Berkowitz, M.D., Ph.D. (RAD). National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: Russell Bowler, M.D., Ph.D. (PI); Adam Friedlander, M.D.; David Lynch, M.B. (RAD); Joyce Schroeder, M.D. (RAD); John Newell, Jr., M.D. (RAD). Temple University, Philadelphia, PA: Gerard Criner, M.D. (PI); Victor Kim, M.D.; Nathaniel Marchetti, D.O.; Aditi Satti, M.D.; A. James Mamary, M.D.; Robert Steiner, M.D. (RAD); Chandra Dass, M.D. (RAD). University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL: William Bailey, M.D. (PI); Mark Dransfield, M.D. (Co-PI); Hrudaya Nath, M.D. (RAD). University of California, San Diego, CA: Joe Ramsdell, M.D. (PI); Paul Friedman, M.D. (RAD). University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA: Geoffrey McLennan, M.D., Ph.D. (PI); Edwin JR van Beek, M.D., Ph.D. (RAD); Brad Thompson, M.D. (RAD); Dwight Look, M.D. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI: Fernando Martinez, M.D. (PI); MeiLan Han, M.D.; Ella Kazerooni, M.D. (RAD). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN: Christine Wendt, M.D. (PI); Tadashi Allen, M.D. (RAD). University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Frank Sciurba, M.D. (PI); Joel Weissfeld, M.D., M.P.H.; Carl Fuhrman, M.D. (RAD); Jessica Bon, M.D. University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX: Antonio Anzueto, M.D. (PI); Sandra Adams, M.D.; Carlos Orozco, M.D.; Mario Ruiz, M.D. (RAD). Administrative Core: James Crapo, M.D. (PI); Edwin Silverman, M.D., Ph.D. (PI)’ Barry Make, M.D.; Elizabeth Regan, M.D.; Sarah Moyle, M.S.; Douglas Stinson. Genetic Analysis Core: Terri Beaty, Ph.D.’ Barbara Klanderman, Ph.D.; Nan Laird, Ph.D.; Christoph Lange, Ph.D.; Michael Cho, M.D.; Stephanie Santorico, Ph.D.; John Hokanson, M.P.H., Ph.D.; Dawn DeMeo, M.D., M.P.H.; Nadia Hansel, M.D., M.P.H.; Craig Hersh, M.D., M.P.H.; Jacqueline Hetmanski, M.S.; Tanda Murray. Imaging Core: David Lynch, M.B.; Joyce Schroeder, M.D.; John Newell, Jr., M.D.; John Reilly, M.D.; Harvey Coxson, Ph.D.; Philip Judy, Ph.D.; Eric Hoffman, Ph.D.; George Washko, M.D.; Raul San Jose Estepar, Ph.D.; James Ross, M.Sc.; Rebecca Leek; Jordan Zach; Alex Kluiber; Jered Sieren; Heather Baumhauer; Verity McArthur; Dzimitry Kazlouski; Andrew Allen; Tanya Mann; Anastasia Rodionova. PFT QA Core, LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT: Robert Jensen, Ph.D. Biological Repository, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD: Homayoon Farzadegan, Ph.D.; Stacey Meyerer; Shivam Chandan; Samantha Bragan. Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO: James Murphy, Ph.D.; Douglas Everett, Ph.D.; Carla Wilson, M.S.; Ruthie Knowles; Amber Powell; Joe Piccoli; Maura Robinson; Margaret Forbes; Martina Wamboldt. Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, CO: John Hokanson, M.P.H., Ph.D.; Marci Sontag, Ph.D.; Jennifer Black-Shinn, M.P.H.; Gregory Kinney, M.P.H. Principal investigators and centers participating in ECLIPSE include: Bulgaria: Y. Ivanov, Pleven; K. Kostov, Sofia. Canada: J. Bourbeau, Montreal; M. Fitzgerald, Vancouver; P, Hernández, Halifax; K, Killian, Hamilton; R. Levy, Vancouver; F. Maltais, Montreal; D. O'Donnell, Kingston. Czech Republic: J. Krepelka, Praha. Denmark: J. Vestbo, Hvidovre. The Netherlands: E. Wouters, Horn. New Zealand: D. Quinn, Wellington. Norway: P. Bakke, Bergen. Slovenia: M. Kosnik, Golnik. Spain: A. Agusti; Jaume Sauleda; Palma de Mallorca. Ukraine: Y. Feschenko, Kiev; V. Gavrisyuk, Kiev; L. Yashina, Kiev. UK: L. Yashina, W. MacNee, Edinburgh; D. Singh, Manchester; J. Wedzicha, London. USA: A. Anzueto, San Antonio, TX; S. Braman, Providence, RI; R. Casaburi, Torrance, CA; B. Celli, Boston, MA; G. Giessel, Richmond, VA; M. Gotfried, Phoenix, AZ; G. Greenwald, Rancho Mirage, CA; N. Hanania, Houston, TX; D. Mahler, Lebanon, NH; B. Make, Denver, CO; S. Rennard, Omaha, NE; C. Rochester, New Haven, CT; P. Scanlon, Rochester, MN; D. Schuller, Omaha, NE; F. Sciurba, Pittsburg, PA; A. Sharafkhaneh, Houston, TX; T. Siler, St Charles, MO; E. Silverman, Boston, MA; A. Wanner, Miami, FL; R. Wise, Baltimore, MD; R. ZuWallack, Hartford, CT. Steering Committee: H. Coxson (Canada); C. Crim (GlaxoSmithKline, USA); L. Edwards (GlaxoSmithKline, USA); D. Lomas (UK); W. MacNee (UK); E. Silverman (USA); R. Tal Singer (Co-chair, GlaxoSmithKline, USA); J. Vestbo (Co-chair, Denmark); J. Yates (GlaxoSmithKline, USA). Scientific Committee: A. Agusti (Spain); P. Calverley (UK); B. Celli (USA); C. Crim (GlaxoSmithKline, USA); B. Miller (GlaxoSmithKline, USA); W. MacNee (Chair, UK); S. Rennard (USA); R. Tal-Singer (GlaxoSmithKline, USA); E. Wouters (The Netherlands); J. Yates (GlaxoSmithKline, USA).

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 HL075478, R01 HL084323, P01 HL083069, U01 HL089856 (E.K.S.), K08HL102265 (P.J.C.), UL1 RR025752, and U01 HL089897 (J.D.C.). The National Emphysema Treatment Trial was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Normative Aging Study is supported by the Cooperative Studies Program/ERIC of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, and is a component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC). The Norway cohort and the ECLIPSE study (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00292552; GSK Code SCO104960) are funded by GlaxoSmithKline. The COPDGene project is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis and Sepracor.

Conception and design: P.J.C., E.K.S. Analysis and interpretation: P.J.C., E.K.S., N.L., M.H.C., T.H.B. Drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.H.C., A.A.L., P.B., A.G., D.A.L., W.A., T.H.B., J.E.H., J.D.C., P.J.C., N.L., E.K.S.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0055OC on June 9, 2011

Author Disclosure: W.A is a full-time employee of GlaxoSmithKline. The ECLIPSE Study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. D.L. has received an educational grant, fees for speaking, and acts as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. E.S. has received grant support for two studies of COPD genetics and consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, and has received consulting fees from Astra-Zeneca and honoraria from Wyeth, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Astra-Zeneca. P.C., M.C., P.B., A.G., T.B., A.L., J.C., J.H., and N.L. do not report any potential conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, Franceschini N, van Durme YM, Chen TH, Barr RG, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet 2010;42:45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Repapi E, Sayers I, Wain LV, Burton PR, Johnson T, Obeidat M, Zhao JH, Ramasamy A, Zhai G, Vitart V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five loci associated with lung function. Nat Genet 2010;42:36–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilk JB, Chen TH, Gottlieb DJ, Walter RE, Nagle MW, Brandler BJ, Myers RH, Borecki IB, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, et al. A genome-wide association study of pulmonary function measures in the Framingham Heart Study. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillai SG, Ge D, Zhu G, Kong X, Shianna KV, Need AC, Feng S, Hersh CP, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, et al. A genome-wide association study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): identification of two major susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho MH, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, Sylvia JS, Ziniti JP, Hersh CP, DeMeo DL, Hunninghake GM, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, et al. Variants in FAM13A are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Genet 2010;42:200–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestbo J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Crim C, Dawber F, Edwards L, Hagan G, Knobil K, Lomas DA, MacNee W, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J 2008;31:869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu G, Warren L, Aponte J, Gulsvik A, Bakke P, Anderson WH, Lomas DA, Silverman EK, Pillai SG. The SERPINE2 gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in two large populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Weinmann G, Wood DE. A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2059–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell B, Rose C, Damon H. The Normative Aging Study: an interdisciplinary and longitudinal study of health and aging. Aging Hum Dev 1972;3:5–17 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Cohn M, Langerman F, Moran S, Tarragona N, Moukhachen H, Venugopal R, Hasimja D, Kao E, et al. The COPD genetic association compendium: a comprehensive online database of COPD genetic associations. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:526–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y., Willer C., Sanna S., Abecasis G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:387–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell S. PLINK (ver 1.07) [accessed December 10, 2010]. Available from http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/

- 14.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 1995;57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baillat D, Hakimi MA, Naar AM, Shilatifard A, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Integrator, a multiprotein mediator of small nuclear RNA processing, associates with the C-terminal repeat of RNA polymerase II. Cell 2005;123:265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes J. D., Flanagan J. U., Jowsey I. R. Glutathione transferases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2005;45:51–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandenberger R, Schmidt A, Linton J, Wang D, Backus C, Denda S, Muller U, Reichardt LF. Identification and characterization of a novel extracellular matrix protein nephronectin that is associated with integrin alpha8beta1 in the embryonic kidney. J Cell Biol 2001;154:447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahai S, Lee SC, Lee DY, Yang J, Li M, Wang CH, Jiang Z, Zhang Y, Peng C, Yang BB. MicroRNA miR-378 regulates nephronectin expression modulating osteoblast differentiation by targeting GalNT-7. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:D5–D16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uhl GR, Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Rose JE, David SP, Niaura R, Lerman C. Molecular genetics of successful smoking cessation: convergent genome-wide association study results. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008;65:683–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann MA, Drury S, Hudson BI, Gleason MR, Qu W, Lu Y, Lalla E, Chitnis S, Monteiro J, Stickland MH, et al. RAGE and arthritis: the G82S polymorphism amplifies the inflammatory response. Genes Immun 2002;3:123–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englert JM, Hanford LE, Kaminski N, Tobolewski JM, Tan RJ, Fattman CL, Ramsgaard L, Richards TJ, Loutaev I, Nawroth PP, et al. A role for the receptor for advanced glycation end products in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2008;172:583–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konishi K, Gibson KF, Lindell KO, Richards TJ, Zhang Y, Dhir R, Bisceglia M, Gilbert S, Yousem SA, Song JW, et al. Gene expression profiles of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:167–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halls ML, Cooper DM. Sub-picomolar relaxin signalling by a pre-assembled RXFP1, AKAP79, AC2, beta-arrestin 2, PDE4D3 complex. EMBO J 2010;29:2772–2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tager IB, Segal MR, Speizer FE, Weiss ST. The natural history of forced expiratory volumes: effect of cigarette smoking and respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988;138:837–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Dockery DW, Wypij D, Fay ME, Ferris BG., Jr Pulmonary function between 6 and 18 years of age. Pediatr Pulmonol 1993;15:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. BMJ 1977;1:1645–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]