Abstract

Post-translational modification of histones provides an important regulatory platform for many DNA-templated processes such as gene transcription and DNA damage repair. It has become increasingly apparent that the misregulation of histone modification, caused by deregulation of factors that mediate its installation, removal and/or interpretation, actively contributes to the initiation and progression of human cancer. In this review, we summarize recent advances in understanding the interpretation of certain histone methylation by PHD finger-containing proteins and how misreading, miswriting and miserasing histone methylation marks are associated with oncogenesis. This quickly emerging field not only provides a greater mechanistic understanding of human cancers, but also may help direct novel therapeutic interventions in future.

Introduction

Modulation of chromatin through covalent histone modification represents one fundamental way to regulate DNA accessibility during gene transcription, DNA replication, DNA damage repair, and many other cellular processes. According to the ‘histone code hypothesis’ (Box 1), the biological outcome of histone modifications is manifested either by direct physical modulation of nucleosomal structure or by providing a signaling platform to recruit downstream ‘reader’ or ‘effector’ proteins1, 2. A rapidly emerging body of evidence suggests that both genetic alterations and epigenetic aberrations contribute to the initiation and progression of human cancers3. For example, aberrant DNA methylation is a common mechanism used by tumor cells to silence tumor suppressor genes4. In this review, we focus on the recent advances that link oncogenesis to histone methylation events, with those occurring at histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) and H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) as paradigmatic examples (Table 1). Here, we propose that epigenetic alternations involving histone modification lead to misregulation of gene expression and perturbation of the states of cell identities, which, in return, contribute to tumor initiation, progression and metastasis.

BOX 1. The histone code hypothesis.

The histone code hypothesis, initially put forward by Allis and colleagues1, 2, refers to an epigenetic marking system using different combinations of histone modification patterns to regulate specific and distinct functional outputs of eukaryotic genomes.

The histone code hypothesis in gene regulation and development

The histone code hypothesis proposes several layers of regulation in the interpretation of the genome. First, the establishment of homeostasis of a combinatorial pattern of histone modification, i.e., the histone code, in a given cellular or developmental context, which is brought about by a series of ‘writing’ and ‘erasing’ events performed by histone modifying enzymes. Here, the ‘writer’ of histone modification refers to an enzyme (for example, a histone methyltranferase) that catalyzes a chemical modification of histones in a residue-specific manner, and the ‘eraser’ of histone modification refers to an enzyme (for example, a histone demethylase) that removes a chemical modification from histones1, 2, 5. Second, the specific interpretation or the ‘reading’ of the histone code; This is accomplished by ‘reader’ or ‘effector’ proteins that specifically bind to a certain type or a combination of histone modification and translate the histone code into a meaningful biological outcome, whether it is transcriptional activation or silencing, or other cellular responses1, 2, 5. In addition to such a recruitment or ‘trans’ mechanism, the manifestation of histone modification can also achieved by direct physical modulation of chromatin structure or alteration of intra- and inter-nucleosomal contacts via steric or charge interaction (for example, neutralization of the positive charges of histones by acetylation of lysines)1–3. All these regulatory mechanisms function broadly to set up an epigenetic landscape that determines cell fate decision-making during embryogenesis and development9, or to fine-tune gene transcriptional regulation at a few gene loci during DNA damage repair13 or in other DNA-templated contexts.

The histone code hypothesis extended to oncogenesis

In the contexts of tumorigenesis or cancer epigenetics, we further hypothesize that alteration in the “balance” between epigenetic ‘gene-on’ versus ‘gene-off’ chromatin states leads to inappropriate expression or silencing of gene programs that, in turn, alter the states of cellular identity. In certain instances and developmental lineages, these alterations lead to unwanted mistakes made in decisions to proliferate versus to senescence and/or differentiate during tumorigenesis.

Table 1.

Deregulation of the ‘writing’, ‘reading’, or ‘erasing’ of histone methylation H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 is associated with the development of human cancers.

| Specificity | Category | Gene ID | Deregulation in human cancer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3/2 | writer | MLL | Rearrangement of MLL commonly found in myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia. | 25 |

| MLL2 | Somatic mutation of MLL2 found in renal cell carcinoma | 94 | ||

| reader |

ING1/ ING2/ ING3/ ING4/ ING5 |

Loss-of-function mutation of putative tumor suppressor gene ING1-5, in form of either somatic mutation, allelic loss, downregulation of expression, or aberrant cytoplasmic sequestration, associates with a variety of solid tumors. A subset of ING2 somatic mutations interferes with the binding to H3K4me3 specifically. | 69–71 | |

| PHF23 | Due to chromosomal translocation, the H3K4me3-binding PHD finger of PHF23 is fused to NUP98 in myeloid leukemia. It has been shown that the H3K4me3 binding is critical for leukemogenesis induced by NUP98-PHF23 oncoproteins. | 21 | ||

| Pygo2 | Pygo2, component of β-catenin signaling pathway, is critical for self-renewal of mammary progenitor cells. Its protein level is high in malignant breast tumors and low in non-malignant breast cells. | 88, 89 | ||

| eraser | JARID1A | Similar to PHF23, the PHD finger of JARID1A is fused to NUP98 in a subset of myeloid leukemia, forming an oncoprotein NUP98-JARID1A. The H3K4me3 binding by the JARID1A PHD finger is critical for leukemogenesis. | 21 | |

| JARID1B | Overexpression of JARID1B was found in advanced breast and prostate cancers. | 91, 93 | ||

| JARID1C | Recurrent inactivating mutation of JARID1C was detected in about 3% of renal carcinoma. | 94 | ||

| JHDM1B* | Up-regulation of JHDM1B represents a common event in a screen for oncogenes that induce retrovirus-induced T cell lymphomas. | 96–98 | ||

| H3K27me3/2 | writer | EZH2 | Over-expression of EZH2 is frequently found in a variety of solid tumors including prostate, breast, colon, skin, and lung cancers; On the other hand, recurrent inactivating mutations or haploinsufficiency of EZH2 is detected in about 10% of follicular lymphoma and 20% of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of germinal center origin. | 54, 63 |

| eraser | JMJD3 | Downregulation of JMJD3 was found in lung and liver cancers. | 100, 101 | |

| UTX | Sporadic inactivating mutations of UTX was reported in a subset of multiple myeloma, esophageal squamous cell carcinomas, renal cell carcinomas and other tumors. | 99 | ||

Gene full name shown as follows: MLL, mixed lineage leukemia; ING, inhibitor of growth; PHF23, PHD finger protein 23; Pygo, pygopus; JARID1, jumonji AT-rich interactive domain 1; JHDM1B, jumonji C domain-containing histone demethylase 1B; EZH2, enhancer of zeste (Drosophila) homolog 2; JMJD3, jumonji domain containing 3; UTX, ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat X chromosome.

Methylation of histones occur at both lysine and arginine resides. Once thought to be very stable, histone methylation is now appreciated as a reversible process. Its homeostasis is mediated by two opposing groups of enzymes, histone methylation ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’, which install and remove histone methylation marks respectively in a site-specific manner1, 5. For example, H3K4 methylation is established by the SET1 and MLL family of histone methyltransferases (HMTs) (Figure 1A)5, and removed by the LSD1 and JARID1 family of histone demethylases (HDMs) (Table 1)6.

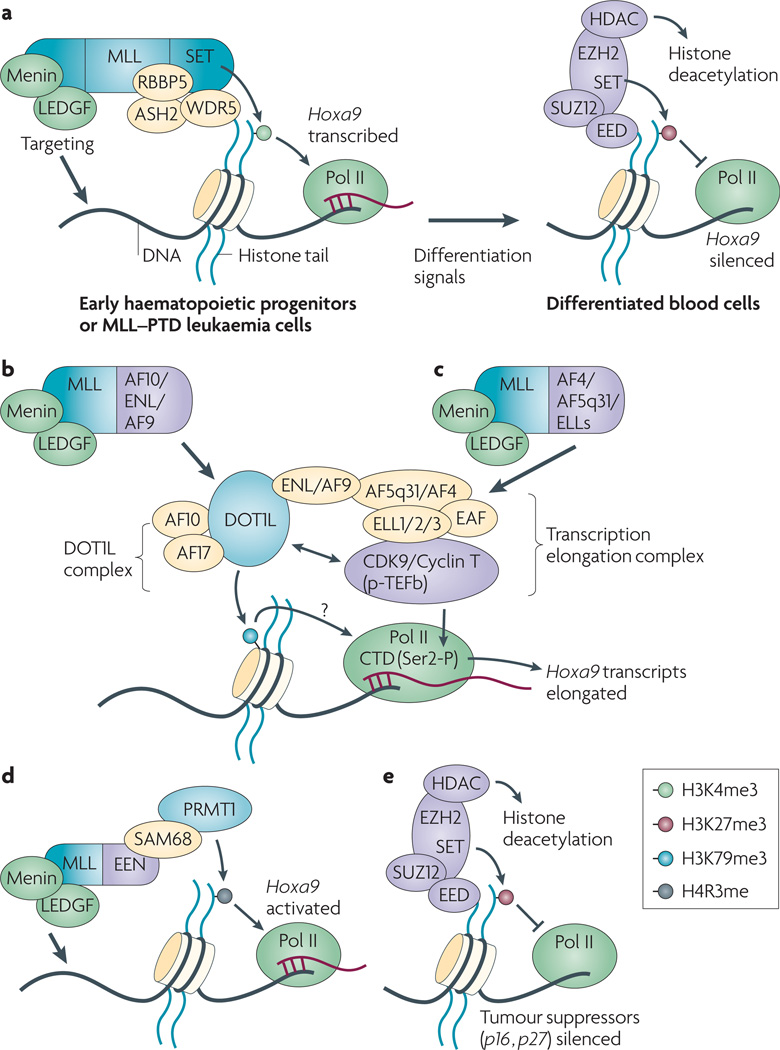

Figure 1. ‘Miswriting’ of histone methylation is associated with the initiation or progression of human cancer.

(a) MLL-containing complexes induce H3K4me3 at Hox genes in early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Following terminal differentiation, a transition of chromatin state occurs at Hox, which is characterized by loss of H3K4me3 and gain of EZH2-mediated H3K27me321, 66. EZH2 polycomb factors and associated HDACs induce the stable silencing of Hox. MLL-PTD, a MLL rearrangement form that harbors a duplication of MLL exon 4–12, causes an elevated level of H3K4 methylation.

(b–d) In leukemia, MLL fusion proteins lose a large carboxyl portion that includes the H3K4me3-‘writing’ SET domain, retain the chromatin targeting factors (Menin and LEDGF), and also acquire aberrant trans-activation mechanisms through its fusion partner. A subset of MLL fusions, MLL-AF10, MLL-ENL and MLL-AF9, directly interact with DOT1L and induce the methylation of H3K79 at Hoxa9 (panel b). Some other MLL fusions, MLL-AF4, MLL-AF5q31 and MLL- ELL1, interact with and recruit p-TEFb transcription elongation complexes to Hoxa9 (panel c). DOT1L-complexes (DOT1L-AF10-AF17-ENL/AF9) associate with p-TEFb complexes via the shared components. Another MLL fusion partner EEN recruits PRMT1 and induce methylation of H4R3 at Hox (panel d).

(e) Over-expression of EZH2 in tumor cells silences the tumor suppressor gene such as INK4B-ARF-INK4A. Please note that EZH2 can regulate oncogenes (panel a) or tumor suppressors (panel e) in different cellular contexts.

Within histone H3, methylation has been observed at multiple lysine (K) sites including H3K4, K9, K27, K36 and K79, and addition of up to three methyl groups at each lysine produces a total of four methyl states - unmethylated, and mono-, di- or tri-methyl. Each of different histone methylation sites and states exhibits a quite distinct distribution pattern in the mammalian genome7. H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) is strongly associated with transcriptional competence and activation, with the highest levels observed near the transcriptional start sites of highly expressed genes, whereas H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) is frequently associated with gene silencing, especially repression of unwanted differentiation programs during lineage specification7–9. Distribution patterns of H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and their associated histone marks underlie the diversity of cellular states for pluripotency and lineage differentiation. For example, in embryonic stem cells, active and repressive histone modifications co-exist and co-mark developmentally critical genes, where a monovalent feature, either active or repressive marks, is often kept in differentiated cell lineages8, 9. It has been proposed that a bivalent chromatin state serves as a mechanism to retain chromatin plasticity and to keep the cell/chromatin state poised at the early stages of embryogenesis and development8, 9. As epigenetics and histone modification are intimately related to cell fate determination, it has been proposed that epigenetic aberration may be involved in early phases of tumor development and establish the state of tumor-initiating cell populations10. Indeed, Esteller and colleagues have reported that the global loss of trimethylation at Lys 20 and acetylation at Lys16 of histone H4 is a hallmark of cancer cells11.

Histone methylation, a component of chromatin indexing mechanisms

One important issue in chromatin biology and epigenetics is to understand how the pattern of a potential ‘histone code’ or ‘epigenetic code’ (Box 1) is translated into the meaningful biological consequence, especially in the context of cell fate determination and gene regulation. Towards this end, identifying factors that specifically recognize or ‘read’ histone modifications has greatly improved our understanding of the interpretation and meanings of these histone marks. A recent breakthrough is the discovery of a specialized group of protein modules termed as plant homeo domain (PHD) finger (Box 2) as the ‘reading’ motif specifically for tri- and di-methylated H3K4 (H3K4me3/2), with H3K4me3 as the preferred ligand12–15 (Table 2). Despite the fact that a large number of PHD finger motifs are encoded by the human genome, only a subset contain the critical hydrophobic or aromatic residues that enable them to form a specialized structural pocket or channel to accommodate the H3K4me3 side chain5 (Box 2). We refer readers to several recent reviews that cover the classification and structure of these histone modification-‘reading’ modules in greater details5, 16, 17. Here, we only focus on how these histone modification ‘reading’ factors are involved in normal cellular processes such as transcriptional regulation and DNA recombination, as well as in oncogenesis.

BOX 2. The plant homeodomain (PHD) finger.

The PHD finger is a zinc finger-like domain, with a signature motif of Cys4-His-Cys3 to coordinate two zinc ions113. The folding of this ~60 amino acid-long domain is featured by an interleaved topology of zinc ion-coordinating residues and a couple of anti-parallel β-sheet secondary structures5, 113. The definition of PHD fingers originates from conserved plant homeodomain proteins, and the classification and distinction of PHD fingers and other similar motifs such as the RING finger are somewhat ambiguous113. There are less than twenty typical and atypical PHD finger motifs in S cerevisiae, about fifty in Drosophila, and up to a couple of hundred in mammals17, 113, 114. Most of PHD fingers are found in chromatin-associated factors or nuclear proteins113, 114.

The PHD finger ligand

PHD fingers exhibit diversity and versatility in terms of their interaction partners. Some binds to chromatin modification such as highly methylated H3K45, unmodified H3K417 and methylated H3K36114, some serve as a SUMO E3 ligase to interact with the E2 conjugating enzyme115, and for others, their binding partner or function is still a mystery.

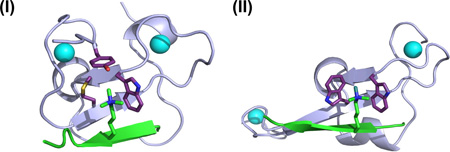

The structure of H3K4me3/2-binding PHD fingers

Recent structural analyses of several H3K4me3/2-binding PHD fingers have revealed some commonalities that underlie the specific recognition and binding of H3K4me3, which include a specialized ‘pocket’ or ‘cleft’ structure formed by 2–4 aromatic and/or hydrophobic residues to accommodate the H3K4me3 side chain, anti-parallel β-sheet pairing between the histone H3 backbone and a β-sheet of the PHD motif, and, in many cases, positioning of H3 arginine 2 (H3R2) in an acidic pocket5, 14–16, 19–21. The structures of H3K4me3-binding PHD fingers from two cancer-associated factors, ING2 and JARID1A, are shown in panel (I) and (II) respectively (H3 and the H3K4me3 side chain shown in green, PHD finger in lavender, zinc ion in cyan sphere, and hydrophobic ‘pocket/cleft’ highlighted in pink; arrows represent β-sheets). With a dissociation constant (Kd) ranging from less than one to several µM, the binding of H3K4me3 by PHD fingers represent one of the strongest associations between histone modification and its ‘reading’ factors5, 14–16, 19–21. The structural illustrations shown are produced using published structural coordinates that have been deposited Protein Data Bank under accessions 2G6Q, 3GL6, 2KGG and 2KGI15, 21.

Table 2.

List of PHD finger-containing proteins that specifically 'read' H3K4me3/2.

| Gene ID† | H3K4me3/2 reading motif |

Known function and disease relevance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPTF | The second PHD finger | Component of a chromatin remodeling complex NURF, which contains a SWI/SNF family helicase/ATPase SMARCA1 | 12, 14 |

| ING1 | PHD finger | Component of HDAC-Sin3A transcriptional repressive complexes | 13, 70, 73 |

| ING2 | PHD finger | Component of HDAC-Sin3A transcriptional repressive complexes | 13, 70, 76 |

| ING3 | PHD finger | Form a transcriptional activation complex with a histone acetyltransferase (HAT) Tip60 | 70, 76 |

| ING4 | PHD finger | Form an HBO-containing transcriptional activation complex | 70, 74–76 |

| ING5 | PHD finger | Component of a transcriptional activation complex that contains a HAT protein, either HBO or MOZ/MORF | 76 |

| JARID1A | The third PHD finger | H3K4me3/2-specific histone demethylase | 21 |

| JARID1B | The third PHD finger | H3K4me3/2-specific histone demethylase | 18, 21* |

| MLL | The third PHD finger | Histone methyltransferase, specific for H3K4 | 5* |

| PHF2 | PHD finger | Putative histone demethylase | 5* |

| PHF8 | PHD finger | Putative histone demethylase; PHF8 mutation associates with X-linked mental retardation. | 5, 18* |

| PHF13 | PHD finger | Unknown function | 5, 18* |

| PHF23 | PHD finger | Unknown function | 21 |

| Pygo | PHD finger | Pygo1/2 interacts with a cofactor BCL9, and is required for Wnt/β-catenin induced transcriptional activation. | 87–89 |

| RAG2 | PHD finger | A V(D)J recombinase critical for the development and maturation of B and T cells. Loss-of-function mutations of the RAG2 PHD finger lead to severe combined immunodeficiency and Omenn syndrome. | 20 |

| TAF3 | PHD finger | Component of RNA polymerase II-associated general transcription factor machinery TFIID, which contains TATA-binding protein (TBP) and 12–13 additional TBP-associated factors, TAF1–14. | 18, 19 |

Gene full name shown as follows: BPTF, bromodomain PHD finger transcription factor; PHF, PHD finger protein; RAG2, recombination activating gene 2; TAF3, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor, 140kDa.

The H3K4me3-binding property was predicted based on domain homology5.

To date, about a dozen of PHD finger-containing readers for H3K4me3/2 have been experimentally confirmed (Table 2), which include a RNA polymerase II-associated general transcriptional machinery component TFIID/TAF3, a V(D)J recombinase RAG2, and several critical chromatin modifying or remodeling factors. Conceivably, the H3K4me3 mark serves as a critical chromatin 'index' or 'beacon', allowing specific genomic regions to be readily recognized by their downstream ‘readers’ and/or associated effectors. For example, it has been suggested that the targeting of TFIID/TAF3 to H3K4me3 at promoters helps to anchor and/or recruit TFIID and associated machinery for active transcriptional initiation (Figure 2a)18, 19. In addition, recognition of H3K4me3 by the PHD finger of RAG2 at V(D)J gene segments has been proven to be critical for efficient V(D)J recombination during B and T cell development and maturation, and deleterious germ-line mutations that abrogate such recognition of H3K4me3 lead to severe immunodeficiency syndromes (Figure 2b)20. Now, emerging evidence also reveals that deregulation in the ‘reading’ of H3K4me3 contributes to various aspects of cellular transformation and even leads to cancers in some case, i.e., acute leukemia induced by chromosomal translocation of the H3K4me3-'reading' PHD finger of PHF23 or JARID1A 21 (Table 1). In addition, many enzymes that mediate the ‘writing’ or ‘erasing’ of histone methylation are also strongly associated with oncogenesis (Table 1). It should be noted that certain histone methylation 'writer' or 'eraser' contains the methyl-'reading' module (e.g. MLL or JARID1A, in Table 1 and 2), which indicates coordination between 'reading' and 'writing'/'erasing' steps of histone modification.

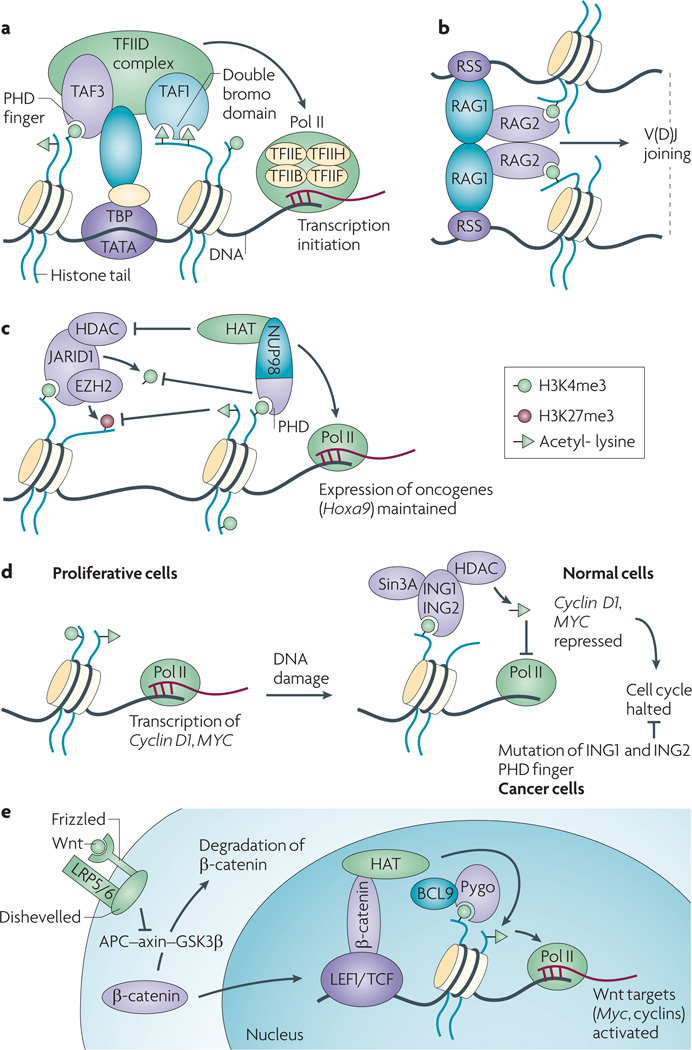

Figure 2. ‘Reading’ or ‘mis-reading’ the H3K4me3 marks by the PHD finger-containing factors in normal cellular processes and during cancer development.

(a) Interaction with histone modification (H3K4me3 recognized by the TAF3 PHD finger18, 19 and histone acetylation by the double bromo domain of TAF116) and the DNA binding (TBP to the TATA box sequences) serve to anchor and/or stabilize the TFIID complex to core promoters, a critical step of the assembly of general transcription initiation machineries for active gene transcription18, 19.

(b) Both recognition of H3K4me3 by the RAG2 PHD finger and binding to the recombination signal sequences (RSS) by RAG1-RAG2 complexes are critical for recruiting and/or stabilizing the RAG1/2 complexes at V(D)J gene segments to be recombined during B and T cell development17, 20.

(c) Chromosomal translocation NUP98-JARID1A or NUP98-PHF23 fuses the N-terminal part of a nucleoporin protein, NUP98, to an H3K4me3-binding PHD finger of JARID1A or PHF23 (left panel)21. Such a NUP98-PHD finger fusion oncoprotein prevents the removal of H3K4me3 presumably mediated by the JARID1 histone demethylase and associated repressive factors (right panel) and enforces the expression of leukemia oncogenes such as HOX and MEIS1 21. Arrows at the bottom indicate the effect of each complex on transcription.

(d) Upon insult of DNA damage, H3K4me3 serves as a mechanism to recruit and/or stabilize the ING protein complexes to genes involved in the regulation of cell proliferation or apoptosis, which is then followed by their repression (in case of ING1/2-HDAC complexes) or activation (in case of ING4/5-HAT complexes)13, 74, 75. A subset of cancer-associated somatic mutations of ING1 specifically interfere with the binding to H3K4me3/2 marks13, 17, 73.

(e) Recognition of H3K4me3 by the PHD finger of Pygopus (Pygo), an interacting cofactor of BCL9 and β-catenin, has been suggested to be critical for efficient activation of Wnt signaling pathway87.

(De)Methylation of histones and beyond

A complication of histone modifying enzymes is the potential involvement of non-histone substrates. Although histone modification ‘writers’ or ‘erasers’ were originally identified as enzymes that modify histones, an increasing body of evidence shows that they may also target non-histone proteins. For example, LSD1 (also known as KDM1A) not only targets its canonical substrate, histone H3, but also demethylates the tumor suppressor p53 at lysine 370 and represses p53 activities22, 23. Similarly, the histone methyltransferase G9a and SET7/9 induce methylation of a number of non-histone proteins23, 24. To our knowledge, none of the histone methyltransferases or demethylases listed in Table 1 has been formally shown to act on non-histone substrates, although it remains an open question and a formal possibility that they target beyond histones. In the following sections, we focus on recent evidence that has linked the mis-writing, mis-interpretation and mis-erasing of the ‘histone code’ to oncogenesis, using mutations affecting H3K4me3-reading PHD finger 'readers' and mutations affecting chemical modification of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 as instructive examples.

Histone methylation miswritten during oncogenesis

Establishment of an appropriate pattern of histone methylation is not only crucial for normal development and differentiation, but is also intimately associated with tumor initiation and development (Table 1). Soon after their discovery, some histone modifying enzymes have been found to be frequently mutated in human cancer. Conversely, some famed cancer-associated genes turn out to be direct regulators of histone methylation much later on after initial cloning.

MLL gene rearrangement in leukemia

The Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) (also known as ALL-1, KMT2A) was initially identified as the gene involving recurrent translocations of chromosomal band 11q23 in human myeloid and lymphoid leukemias25, and was later shown to encode a major H3K4-specific HMT enzyme26, 27. MLL forms a large macromolecular nuclear complex with the core complex components (WDR5, RBBP5, ASL2), and induces H3K4me3 for efficient transcription5, 26, 28 (Figure 1a). Other MLL-associated factors, Menin and LEDGF, tether the MLL complex to appropriate targets29(Figure 1a). Accounting for about 80% of infant leukemia and 5–10% of adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or lymphoid leukemia cases, MLL gene rearrangements represents one of the most common chromosomal abnormalities found in human leukemia25, 30.

The partial tandem duplication of MLL (MLL-PTD), the most frequent form of MLL rearrangement in AML30, 31, contains an in-framed duplication of MLL exon 4 to 11 (or exon 4 to 12) and retains the H3K4 HMT activity25(Figure 1a). Dorrance et al have recently generated an MLL-PTD knock-in mouse model and found that MLL-PTD causes aberrant elevation of H3K4 dimethylation and histone acetylation of the Hox-A gene cluster32, 33(Figure 1a). Over-expression of Hox genes initiates and/or promotes leukemia induction34. Normally, the expression of Hox-A genes such as Hoxa9 is developmentally restricted – they are highly expressed in early hematopoietic precursors and silenced following differentiation35(Figure 1a). In the MLL-PTD knock-in mice, altered histone methylation and/or acetylation correlates with a significant increase in in vitro colony formation potentials of erythroid, myeloid, or pluripotent hematopoietic progenitors, as well as a drastic increase in Hoxa9 expression among terminally differentiated blood cells (by 100~250 fold increase) and unsorted hematopoietic tissues (by 4~150 fold)32, 33. However, these MLL-PTD knock-in mice fail to develop frank leukemia, indicating that additional alternations are required for malignant transformation.

MLL fusion, a second type of MLL gene rearrangement, results in deletion of a large C-terminal fragment, which includes the H3K4 HMT domain, and also acquisition of additional transformation mechanisms provided by MLL fusion partner25, 36(Figure 1b,c,d). Over fifty different MLL fusion partners have been identified in leukemia25, 36. Although leukemogenic mechanisms underlying many rare MLL fusion forms are poorly understood, recent studies have started to unveil a common transformation pathway for the most frequent MLL fusion forms (Figure 1b,c). Okada et al first report that the AF10 portion of MLL-AF1037 and CALM-AF1038 fusions directly recruits DOT1L (also known as KMT4), a histone methyltransferase that mediates or ‘writes’ the methylation of histone H3 lysine 79 (H3K79me)37(Figure 1b). This scenario can be applied to MLL-ENL, because ENL also directly associates with DOT1L and the interaction surface is retained in MLL-ENL39(Figure 1b). Aberrant induction of H3K79me was observed at leukemia-promoting oncogenes (such as Hoxa9, Figure 1b) in leukemia cells transformed by MLL-AF1037, MLL-ENL39, 40, MLL-AF441, 42 and MLL-AF943, which represent the most common MLL fusion forms. Mutations of MLL-ENL39 or CALM-AF1038 that disrupt the interaction with DOT1L abolish leukemia transformation. DOT1L and H3K79me are associated with active transcription44, especially at MLL fusion target loci37, 41, thus providing a potential mechanism for aberrant transcriptional activation found in leukemia. DOT1L and by inference H3K79me has been also found involved in cell cycle progression45, silencing of telomere-proximal genes46, and regulation of Wnt signaling target genes47. Recent biochemical studies have further revealed that DOT1L actually associates with an amazingly long list of factors that are known MLL fusion partners, which include AF1037, 47–49, ENL39, 47, 49, AF947–50, AF1747, AF4 (also known as MLLT2 or AFF1)39, 47, 48, AF5q31 (also known as MCEF or AFF4)39 and LAF439. AF10, AF17, and ENL (or AF9) were identified as stable components of DOT1L-containing complexes47. It remains as an intriguing model that DOT1L is responsible for aberrant transcription in many MLL fusion-induced leukemia, however, it has been complicated by the fact that DOT1L complexes are also linked to transcription elongation. Via a protein-protein interaction network, DOT1L-AF10-ENL/AF9 complexes further associate with a transcription elongation-promoting complex that contains AF5q31/AFF4, AF4, ELL1/2/3 (also known MLL fusion partners), and the Pol II transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) kinase (consists of CDK9 and Cyclin T1/2a /2b)39, 51 (Figure 1b,c). ENL and AF5q31/AFF4 are shared components of these two complexes39, 47, 49, 51. In addition, two recent studies further demonstrate that MLL fusions involving component in this elongation complex, including MLL-AF4, MLL-ENL, MLL-AF9, and MLL-ELL1, all interact with AF5q31/AFF4 and recruit p-TEFb transcription elongation complexes to promote the transcription of downstream targets such as Hox51, 52 (Figure 1c). Thus, mechanisms underlying aberrant transactivation in MLL leukemia have been linked to H3K79me and also transcription elongation.

While the activities of P-TEFb complexes during transcription were well established, the role of H3K79 methylation in transcription suffers from lack of mechanistic understandings. Is H3K79me equally important, or does DOT1L merely bridge MLL fusions (such as MLL-ENL or MLL-AF10) to P-TEFb elongation complexes (Figure 1b)? Several lines of evidence suggest that H379me is critical in leukemia induction. First, replacing the AF10 fragment of MLL-AF10 with the wildtype but not catalytically inactive form of DOT1L succeeded in leukemia transformation37. Second, inhibition of DOT1L by knockdown significantly interferes with MLL-AF4 induced transformation and also the activation of Hox genes41, although MLL-AF4 associates with AF5q31/AFF4 and p-TEFb elongation complexes51. In addition, DOT1L also directly interacts with p-TEFb52. Further investigation will be needed to examine the role of H3K79me during transcriptional activation or elongation.

Another MLL fusion, MLL-EEN, recruits histone arginine methyltransferase PRMT1, and its methyltransferase activity towards histone H4 arginine 3 has been shown to be critical for leukemia transformation53 (Figure 1d). Taken together, miswriting of histone methylation marks often correlates with aberrant transcription of oncogenes in leukemia patients harboring MLL gene rearrangements.

EZH2 over-expression and mutation in cancers

EZH2, an H3K27-specific methyltransferase or ‘writer’, provides another connection between miswriting histone methylation marks and oncogenesis. EZH2 is frequently found over-expressed in a wide variety of solid tumors including prostate, breast, colon, skin, and lung cancers54, 55 (Table 1). Suppression of EZH2 by RNA interference significantly decreased tumor growth in breast and prostate tumor xenograft models56, 57. Furthermore, over-expression of EZH2 confers invasiveness to fibroblasts and immortalized benign mammary epithelial cells, and this effect is dependent on the H3K27 HMT activity of EZH257–59. Mechanistically, the oncogenic function of EZH2 polycomb factor has been attributed to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes including INK4B-ARF-INK4A 55 (Figure 1e), E-cadherin58, 60, p57KIP2/CDKN1C61, p2762, BRCA156, and adrenergic receptor β257. Contrary to the overwhelming evidence showing EZH2 overexpression in tumors, a recent next-generation sequencing based study of human cancer genomes discovered the recurrent inactivating mutations of EZH2 in follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma63 (Table 1). The identified EZH2 mutations specifically target a single tyrosine residue that is required for EZH2-mediated HMT activities towards H3K27me363. It is tempting to speculate that the homeostasis of H3K27me3 mark might be disrupted through deregulation or mutation of EZH2, however, the oncogenic roles of EZH2 over-expression and mutations remain to be validated more rigorously in genetically engineered animal models in future. Ideally, genomic (mis)-localization of EZH2 and its effect on H3K27me3 or transcription need to be examined in matched normal versus tumor samples.

Despite these, blockade of EZH2 has been proposed a therapeutic strategy to inhibit tumorigenesis and initiate tumor regression54. Indeed, Fisku et al show that combined usage of inhibitors of EZH2 and HDACs, another type of repressors that physically interact with EZH2 (Figure 1e), de-repress several tumor suppressor genes (p16, p19 & p27), selectively induces apoptosis of leukemia cells, and improves survival of mice bearing xenograft leukemia64. Due to the limited space, we also refer readers to recent nice reviews54, 55, where the involvement of EZH2 in oncogenesis is discussed in greater details.

Histone methylation misinterpreted during oncogenesis

1. Aberrant fusion of PHD finger motifs and mis-interpretation of H3K4me3 in leukemia

Chromosomal translocation of nucleoporin-98 (NUP98), a nuclear pore complex component gene, represents one of the most promiscuous gene rearrangements found in various forms of hematopoietic malignancies65. In a subset of AML patients, NUP98 translocation results in fusion of the N-terminus of NUP98 to the C-terminal PHD finger motif (and also nuclear localization signals) of PHF23 or JARID1A (also known as KDM5A or RBBP2) (Figure 2c)21, 65. Recently, leukemia induced by NUP98-JARID1A or NUP98-PHF23 fusion has been experimentally recapitulated using in vitro and in vivo leukemia models21. The leukemogenic potential of these two fusion oncoproteins relies on the ability of the PHD finger motif to recognize the H3K4me3/2 marks21 (Box 2). A single point mutation in the PHD finger that abrogates the H3K4me3 binding also abolishes leukemic transformation, and the PHD finger can be functionally replaced by other H3K4me3-binding PHD fingers (even one from yeast), but cannot by those that do not recognize H3K4me321. Mechanistically, binding of H3K4me3 by the NUP98-PHD finger fusion interferes with normal differentiation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells by preventing the removal of H3K4me3 and inhibiting EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 at developmentally critical genes Hox, Meis1a, Gata3 and Pbx121, 66. As a result, the chromatin state at master regulator loci of hematopoiesis is locked in an active one (marked with high levels of H3K4me3 and histone acetylation), and the expression of these genes is maintained21. It has been well documented that over-expression or activating mutation of these transcriptional factors such as Hoxa9, Pbx1, and Meis1a is commonly found with human leukemia, and also sufficient to arrest hematopoietic differentiation and induce leukemia34, 67. Thus, perturbation of histone modification dynamics associated with hematopoiesis, as in the case of NUP98-PHD finger fusion, causes enforced expression of critical developmental genes and interferes with appropriate transition of cellular states, which represents a critical step of leukemia initiation21.

As acute leukemia is a disease of misregulated differentiation, it becomes important to first understand molecular mechanisms that underlie the establishment and transition of the chromatin landscape during hematopoietic development. Understanding this issue will also help us to dissect how leukemia lesions such as NUP98 or MLL translocation interfere with the dynamic regulation of chromatin. Conceivably, NUP98-PHD finger fusions may mimic some endogenous chromatin-associated machinery, acting as a chromatin boundary factor that prevents the intrusion of the repressive complexes that include an H3K27me3 ‘writer’ EZH2 and an H3K4me3 ‘eraser’ JARID121, 68 (Figure 2c and Figure 3a). Gain-of-function mutation of the PHD finger motif, as exemplified by NUP98-PHD finger fusions in leukemia21, and loss-of-function mutation of the PHD finger, as mentioned earlier in the case of RAG2 and immunodeficiency syndromes20, unveil a type of human pathologies that are underscored by failure in appropriate interpretation of histone modification17.

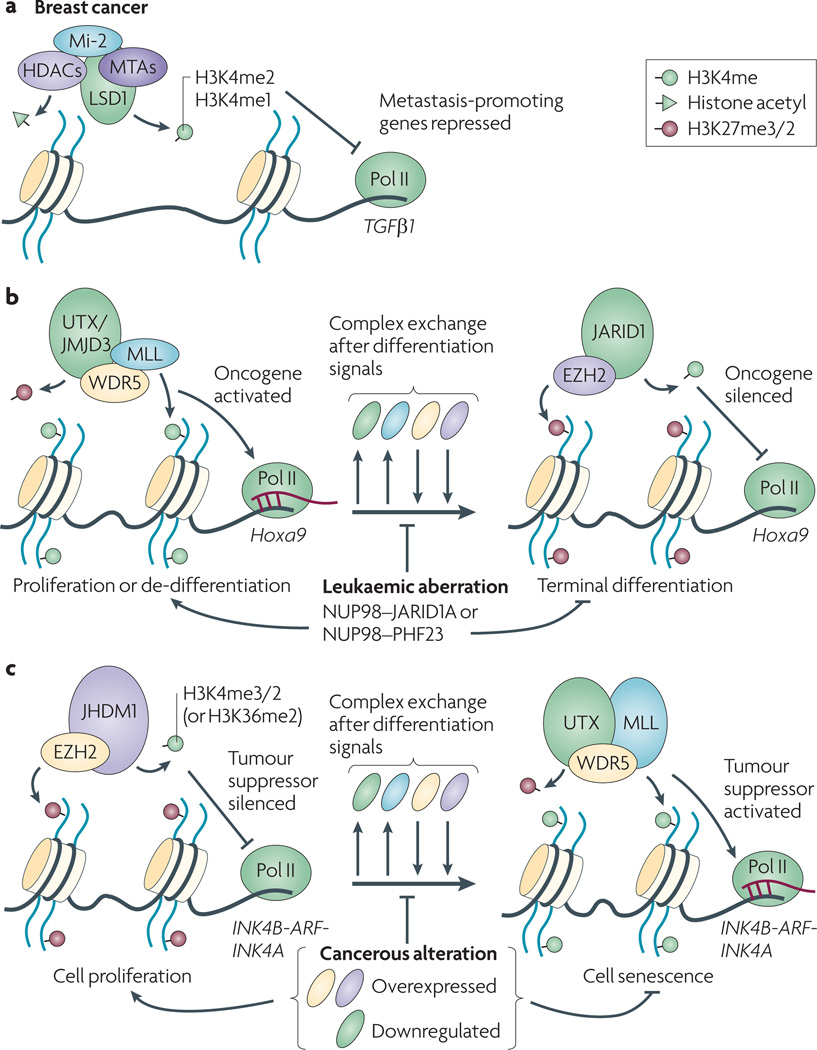

Figure 3. Physical interaction between histone methylation ‘writers’ and ‘erasers’ ensures a robust response during the transition of chromatin states, and such cooperation is also observed during cancerous transformation.

(a) Cooperation between histone methyltransferases and demethylases, exemplified by MLL-JMJD3 interaction104 and EZH2-JARID1 interaction68, underlies a dynamic change in H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 at leukemia-associated oncogenes such as HOX, a process that is perturbed by leukemia oncoproteins such as NUP98-JARID1A or MLL-fusion in leukemia21, 25.

(b) Upon RAS signaling-induced oncogenic stress or the replicative stress, switch of histone methyltransferases and demethylases underlies activation of the tumor suppressor locus INK4B-ARF-INK4A and induction of senescence, a mechanism to prevent cancerous transformation96–98, 100, 101, 116. In cancer cells, over-expression of EZH2 and JHDM1, or down-regulation of JMJD3, interferes with such a switch of chromatin state and thus senescence response100, 101, 117.

2. Somatic mutation of ING PHD fingers in solid tumors

Another family of PHD finger-containing proteins, inhibitor of growth (ING), are putative tumor suppressors. Loss-of-function mutations of INGs (especially ING1, ING3 and ING4) via somatic mutation, allelic loss, reduced gene expression, or aberrant cytoplasmic sequestration, were reported in a variety of solid tumors (Table 1)69, 70. INGs regulate many cellular processes associated with tumorigenesis, including cell cycle progression, senescence, apoptosis, DNA repair, cell migration and contact inhibition69–72. A structural characteristic of all INGs is a PHD finger that locates at C-terminus and binds to H3K4me3 specifically (Box 2)13, 73–75. Despite this common feature, different INGs are incorporated into protein complexes with distinct properties in transcriptional regulation (Table 2). ING1 and ING2 recruit the mSin3- HDAC transcriptional repressors (Figure 2d), whereas INGs3/4/5 recruit histone acetyltransferase (HAT) to induce gene activation13, 76. ING3- and ING4-complexes contain a HAT protein, either Tip60 or HBO respectively, and ING5-complexes include either HBO or MOZ/MORF as the HAT74, 76. INGs (ING1, ING4 and ING5) also interact with p53, and modulate its activity69, 77–79. Here, we focus on recent advances that link ING mutations to mis-interpretation of histone methylation in cancerous transformation.

ING1 was initially identified in a functional screen as an inhibitor of neoplastic transformation80, and somatic mutation of ING1 is later found in breast, gastric, and pancreatic cancers, as well as squamous cell carcinomas69, 70. Deletion of Ing1 in mice only led to a mild phenotype, with a slight increase in incidence of lymphomas, indicating that other mutations may cooperate with ING1 inactivation in tumorigenesis77. A subset of ING1 somatic mutations found in human tumor samples specifically target its PHD finger motif17, 69–71. Some hotspot mutations, C215S and C253stop (amino acid number refers to the p33ING1b isoform), target the critical zinc ion-coordinating cysteines in the PHD finger, which causes a global misfolding17. A recent biophysical study demonstrated that several other ING1 mutations, N216S, V218I and G221V, interfere with either appropriate formation of the structural pocket to accommodate H3K4me3 or appropriate positioning of the histone H3 tail, leading to a decrease in H3K4me3-binding affinities by 10–40 fold73. Despite these advances, animal models that establish a direct causal role of ING1 mutations in tumorigenesis are still lacking. Nonetheless, at the cellular level, it has been shown that the decreased binding of ING1 to H3K4me3 results in an inefficient response to DNA damage or apoptosis73.

ING2, an ING1 related member that is also found downregulated in many types of solid tumors69–71, initiates an acute response aimed at silencing proliferative genes including Cyclin D1 and c-MYC and decelerating the cell cycle upon insults of DNA damage13 (Figure 2d). This response relies on the ability of ING2 to bind to H3K4me3 associated with proliferative genes, followed by the recruitment and/or stabilization of ING2-associated repressors HDAC1 and HDAC213, 76 (Figure 2d). Eventually, histone deacetylation occurs at proliferative genes, their expression is downregulated, and the cell cycle progression is halted13. Since the H3K4me3 level at these genes stays the same before and after DNA damage13, it remains poorly understood what causes the recruitment of ING2 to proliferative genes upon DNA damage. Recently, the association of ING2 with chromatin has been linked to phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate (PtdIns(5)P), a lipid ligand of ING2 that was found accumulated in the nucleus upon cellular stress13, 81. The binding surface for PtdIns(5)P in ING2 is located at the very carboxyl terminus, which include a small portion of the PHD finger and a lysine/arginine-rich polybasic region82. This polybasic region is found in ING1/2 only, and not in other ING members69, 71. Further investigation is required to dissect how multivalent interactions between INGs, signaling transducers, and histone modifications are coordinated to execute an efficient response to DNA damage and cellular stress.

Down-regulation, allelic loss, or somatic mutation of ING3 and ING4 was also found in cancers69, 70. Recognition of H3K4me3 has shown to be critical for ING4/5-HBO complexes to promote genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis and to inhibit anchorage-independent cell growth74–76. Association between the ING4/5 PHD finger and H3K4me3 modulates the substrate specificity of HBO complexes, making H3K4me3-containing nucleosomes a preferred substrate74, 75. Using genome-wide ChIP-chip analyses, Hung et al observed that, after DNA damage, the recruitment of ING4-HBO complexes to the downstream targets is enhanced, followed by the subsequent increase in levels of H3 acetylation and transcription75. Confirmed target loci include a number of tumor suppressor genes such as PHD2 (also known as EGLN1/HPH2) and Exostosin-1 (EXT1)74, 75. PHD2 is an inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), and its down-regulation results in increased angiogenesis in tumor tissues and promotion of tumorigenesis83. Mutation in EXT1 or the related gene EXT2 is responsible for multiple osteochondromas, a skeletal disease characterized by benign bone tumors84. The involvement of misregulation of these potential tumor suppressors need to be further examined in primary tumor samples or animal models harboring loss of ING4.

One interesting issue is that, despite the fact that ING1/2 and ING3/4/5 complexes impart opposite effects on transcriptional regulation71, 76, both types of ING complexes appear to harbor tumor suppressive activities72. Apparently, different INGs target different sets of genes – oncogene vs tumor suppressor loci13, 75. However, this targeting specificity of distinct INGs cannot be determined by their PHD fingers, as they all bind to H3K4me3. Nevertheless, ‘reading’ of H3K4me3 by the PHD finger is a critical step for efficient chromatin binding and for execution of DNA damage- or stress- induced responses13, 73–75. Many other outstanding questions remain unsolved, for example, do different ING-containing complexes cooperate and how interaction of p53 or other DNA binding factors is involved in these cellular responses79? It is also getting important to appreciate how all the following events are integrated: sensing and signaling of DNA damage, assembly and recruitment of ING complexes, chromatin recognition and modulation, the subsequent transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and chromatin restoration post repair.

3. Pygopus (Pygo), a factor that links the Wnt/β-catenin signaling to H3K4 methylation

Mutations in components of Wnt/β-catenin pathway lead to oncogenesis in several tissue types85. Pygopus (Pygo) has recently been identified as a critical factor for efficient Wnt/β-catenin signaling85, 86. Pygo interacts with BCL9 (also known as legless in Drosophila), an adaptor protein that directly associates with β-catenin (Figure 2e)87. The C-terminus of all Pygo homologues (pygopus in Drosophila, and Pygo1/2 in mammals) contains a PHD finger, which uses two surfaces to interact with BCL9 and H3K4me2/3 simultaneously (Figure 2e), and the binding of H3K4me2/3 by Pygo is enhanced by its association with BCL987. Pygo2 was found highly expressed in mammary progenitor cells and up-regulated in breast cancer cells, and the H3K4me2/3-binding property of Pygo2 appears to be critical for cell growth of breast cancer cells88, 89. However, a separate study indicates abolition of interaction between H3K4me2/3 and pygopus does not seem to interfere with the activation of Wnt signaling in fruit flies87, 90. Further investigation of cross-talk among pygopus, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and histone modification needs to be performed to address the difference.

Histone methylation miserased during oncogenesis

Histone lysine demethylases (HDM), especially those acting on H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, are found mutated or deregulated in human cancer (Table 1). JARID1A was found translocated in myeloid leukemia (Figure 2c). JARID1B (also known as PLU-1/KDM5B), another H3K4me3/2-specific HDM gene, was found to be over-expressed in advanced stages of breast and prostate cancers91, 92. JARID1B facilitates the G1/S transition and attenuates the mitotic spindle checkpoint of cancer cells91, 93. Using a syngeneic tumor implantation model, Yamane et al showed that JARID1B over-expression promotes the growth of mammary carcinoma91. JARID1B represses metallothionein genes and several known tumor suppressor genes (BRCA1 and Caveolin-1) by inducing the erasion of H3K4me3/291, 93. In a recent large-scale next-generation sequencing of primary renal cell carcinomas (RCC) genomes, Dalgliesh et al discovered a number of recurrent mutations that inactivate histone modifying enzymes, including truncating mutations of JARID1C (~3% of all RCC samples) and SETD2 (~3%), a histone H3 lysine 36-specific methyltransferase gene94. Inactivation of JARID1C, a third member of the H3K4me3/2-specific HDM genes, in RCC tumor samples is correlated with transcriptional alteration of a specific gene signature94. The majority of RCCs harboring JARID1C mutation also contain a mutation at von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene, a negative regulator of HIF, suggesting that the JARID1C and VHL mutations may cooperate in driving tumorigenesis of RCC94. It is curious that both overexpression and loss-of-function mutations of the JARID1 gene family are suggested to contribute to oncogenesis, although in different cancer types (Table 1).

JHDM1B (also known as FBXL10/Ndy1/KDM2B) and JHDM1A (also known as FBXL11/Ndy2/KDM2A) encode another family of histone demethylases that appear to harbor dual methylation-erasing activities for H3K36me2/1 and H3K4me395–97. In a screen based on retroviral integration-induced T cell lymphomas, Pfau et al found that up-regulation of JHDM1B/Ndy1 is a common event in T cell lymphomas98. JHDM1B/Ndy1 directly represses the tumor suppressor locus, Ink4b-Arf-Ink4a, by erasing H3K36me2 and/or H3K4me396–98. Both JHDM1B/Ndy1 and related protein JHDM1A/Ndy2 are shown to inhibit the replicative senescence and oncogene-induced senescence, which represent a critical barrier of oncogenesis96–98. JHDM1B/Ndy1 is down regulated upon senescence induction in normal tissues, while acquired expression of JHDM1B/Ndy1 in tumors prevents an occurrence of cell senescence, thus facilitating cancerous transformation (Figure 3b)96, 97.

Sporadic inactivating mutations of UTX, an H3K27me3/2-specific HDM gene, have been recently reported in a subset of multiple myeloma, esophageal squamous cell carcinomas, and renal cell carcinomas99. Restoration of UTX in UTX-mutated cancer cells reduced H3K27me3 at tested targets and slowed cell proliferation99. JMJD3, a related H3K27me3/2-specific HDM gene, was found up regulated during RAS-induced senescence, and opposite to the action of JHDM1 and EZH2, JMJD3 activates the Ink4a-Arf locus100, 101 (Figure 3b). The expression of JMJD3 has been found down regulated in various cancers including lung and liver cancers100, 101. These observations indicate a putative tumor suppressive role of UTX and JMJD3. Despite emerging evidence that links HDMs to cancer, it remains to be investigated whether or not the observed mutation is causal or merely the consequence of tumorigenesis using more rigorous assays.

Cooperation of ‘writing’, ‘reading’ and ‘erasing’ of histone methylation in oncogenesis

One complication of classification of ‘writing’, ‘reading’ and ‘erasing’ histone modifications is that these processes often act in a concerted way. For example, some histone modification ‘writer’ or ‘eraser’, such as MLL or JARID1A, harbors an intrinsic PHD finger module to ‘read’ H3K4me3 - the enzymatic product or substrate of these enzymes respectively (Table 2). Currently, it is unclear how this ‘reading’ property is involved in the ‘writing’ or ‘erasing’ step of histone methylation. In context of leukemia induction, NUP98-JARID1A (Figure 2c), a translocation form of JARID1A, loses the histone methylation-‘erasing’ activity, and relies on the H3K4me3-‘reading’ PHD finger to initiate leukemogenesis21. In addition, histone modifiers often work together to take on different histone modification sites simultaneously and to execute a robust response. For instance, UTX is a stable component of the MLL2/3-containing complexes, which ‘erase’ H3K27me3 and also ‘write’ H3K4me3 at target chromatin 102. Consistent to the action of UTX, MLL has recently been found to be recruited to the Ink4a locus in oncogene-induced checkpoint response, and UTX and MLL may cooperate to promote p16/INK4a expression and suppress cancerous transformation103 (Figure 3b). Similarly, JHDM1B/Ndy1 and JARID1A was reported to interact with EZH268, 97, and JMJD3 interacts with MLL104. Here, a common theme appears to underlie the repression process of tumor suppressor INK4B-ARF-INK4A in cancer cells, that is, deregulated histone demethylases (JARID1B, JHDM1B, UTX, JMJD3) cooperate with EZH2 over-expression or DNA hypermethylation to establish a stable silenced state by elimination of active modifications (H3K4me3) and addition of repressive chromatin modifications (H3K27me3 or DNA methylation) (Figure 3b).

Conclusions and future directions

In summary, histone modification, as exemplified by H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 in this review, provides a critical regulatory means for gene transcription, DNA recombination, DNA damage repair, and many other DNA-templated processes. A rapidly increasing body of evidence has indicated that ‘miswriting’, ‘misreading’, or ‘mis-erasing’ of histone modifications contributes to the initiation and development of human cancer. However, in terms of mechanistic understandings, the picture is still rather murky, complicated and context-dependent. First, it is unclear how the gene target specificity of many histone modifying or modification-‘reading’ factors is achieved. For example, recruitment of different sets of INGs to distinct genomic loci cannot be explained by the recognition of H3K4me3. Although Menin and LEDGF were found to be required to tether MLL to its targets29, it is far from clear how MLL fusions are targeted to their downstream genes (such as Hox) in leukemia. Besides histone modification that we focus on, DNA binding factors and their associated co-activators/co-repressors can be equally important in tethering histone modification-associated enzymatic, remodeling and ‘reading’ factors to appropriate chromatin loci. Due to limitation in space, we refer readers to some comprehensive reviews on this topic105, 106.

Second, it remains unclear whether many mutations mentioned above are the cause or consequence. More rigorous evidence is generally lacking to establish causality for deregulation that targets the ‘writing’, ‘reading’ and ‘erasing’ of histone modification. Generating animal models with ING mutations will not only define their oncogenic roles, but also may serve as a useful tool to understand mechanisms for driving oncogenesis. Similar issues can be applied to the inactivating mutations of JARID1C found in renal carcinoma94 or for EZH2 in germinal center B-cell lymphoma63.

Furthermore, the regulatory mechanisms via histone modification can be cell type or context specific. In order to dissect misregulation of histone modifications and epigenetic imbalances in cancer cells, it becomes important to understand how normal cells utilize dynamic chromatin modifications to maintain the appropriate epigenetic balance between crucial oncogenes (e.g. HOX-A gene cluster in hematopoietic lineages) or tumor suppressor genes (e.g. INK4B-ARF-INK4A cluster) in normal developmental and cellular contexts. For example, although DOT1L-mediated H3K79me and transcriptional elongation has been proposed as mechanism responsible for aberrant transcriptional activation in MLL fusion induced leukemia (Figure 2b,c), they fail to explain why MLL fusions, but not wildtype MLL, are refractory to the silencing mechanism that is able to turn off MLL targets in hematopoiesis. Recently, it has been shown that artificial addition of the PHD fingers of MLL, a portion not retained in MLL fusions, is able to inhibit MLL fusion induced transformation107, 108. Loss of such an inhibitory mechanism was proposed to make MLL fusions a constitutive activator107, 108. This inhibitory effect appears to be due to recruitment of the repressive proteins cyclophilin-33 (Cyp33) and HDACs by the third PHD finger of MLL108 or inhibition of MLL fusion targeting by MLL PHD fingers107. The third PHD finger of MLL was predicted to bind to H3K4me3/25. Cyp33 as ligand of the PHD finger has only been reported for MLL so far108, thus this mechanism may be MLL specific. Further efforts need to dissect how the PHD fingers distinguish MLL and their leukemia fusion forms in terms of transcriptional regulation.

Finally, as some histone modifying enzymes also act on non-histone substrates23, 24, 109, it becomes difficult to ascribe observed results to histone modification alone. Experiments need to be carefully designed, ideally with application of a combination of approaches and methodologies, to dissect the effects that originate from histone modification.

Is it prime time for therapeutic intervention of epigenetic players that modify or interpret chromatin modifications? The first and foremost goal is to identify the critical epigenetic factors that have well-defined roles in the initiation or development of cancers. For example, the H3K4me3-binding ‘pocket’ is a potential therapeutic target for treatment of leukemia harboring translocations NUP98-JARID1A or NUP98-PHF2321. In addition, many histone modifying enzymes are ideal targets as their enzymatic activity is druggable54. However, the enthusiasm of developing such inhibitors can be curbed by a general concern of potential side effect and complications. For example, the H3K4me3-binding ‘pockets’ of different PHD finger proteins (Table 2) display a high structural similarity14, 15, 19, 21, and these factors are involved in several critical cellular processes such as general transcription18. Yet, we remain confident that further investigation will lead to discovery of relatively specific druggable epigenetic factors that represent the ‘Achilles heel’ of tumor cells. In support, clinical success of HDAC inhibitors in cutaneous T cell lymphoma and DNA demethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome offers a compelling argument4, 110, 111. Recently, a genomic study has shown that pharmacological doses of all-trans retinoic acid induces a relative specific effect on histone H3 (de)acetylation in PML-RARα fusion-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia cells (PML), and the change on H3 acetylation underlies differentiation therapy and epigenetic therapy of PML112. This study also provides a rational for developing HDAC inhibitors as an alternative therapy for PML patients that are refractory to current standard treatment. With the rapidly growing attention and new discoveries of epigenetic factors that function to govern a steady-state balance or the output of histone modifications, there is considerable promise and excitement on the horizon.

Acknowledgement

Funding for C.D.A. is provided by the NIH Merit Grant GM 53512 and a grant from the Starr Cancer Consortium. P.C. is a Medical Oncology fellow of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and G.G.W. is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Fellow. We thank Drs Alex Ruthenburg and Zhanxin Wang for the critical reading of this manuscript and help on illustration.

Reference

- 1.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang GG, Allis CD, Chi P. Chromatin remodeling and cancer, Part I: Covalent histone modifications. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007;128:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klose RJ, Zhang Y. Regulation of histone methylation by demethylimination and demethylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barski A, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein BE, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen TS, et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature. 2007;448:553–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraga MF, et al. Loss of acetylation at Lys16 and trimethylation at Lys20 of histone H4 is a common hallmark of human cancer. Nat Genet. 2005;37:391–400. doi: 10.1038/ng1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wysocka J, et al. A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2006;442:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature04815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi X, et al. ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature. 2006;442:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature04835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, et al. Molecular basis for site-specific read-out of histone H3K4me3 by the BPTF PHD finger of NURF. Nature. 2006;442:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature04802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pena PV, et al. Molecular mechanism of histone H3K4me3 recognition by plant homeodomain of ING2. Nature. 2006;442:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature04814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1025–1040. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker LA, Allis CD, Wang GG. PHD fingers in human diseases: Disorders arising from misinterpreting epigenetic marks. Mutat Res. 2008;647:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeulen M, et al. Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell. 2007;131:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Ingen H, et al. Structural insight into the recognition of the H3K4me3 mark by the TFIID subunit TAF3. Structure. 2008;16:1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews AG, et al. RAG2 PHD finger couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2007;450:1106–1110. doi: 10.1038/nature06431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang GG, et al. Haematopoietic malignancies caused by dysregulation of a chromatin-binding PHD finger. Nature. 2009;459:847–851. doi: 10.1038/nature08036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, et al. p53 is regulated by the lysine demethylase LSD1. Nature. 2007;449:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature06092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan F, Shi Y. Epigenetic regulation: methylation of histone and non-histone proteins. Sci China C Life Sci. 2009;52:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims RJ, 3rd, Reinberg D. Is there a code embedded in proteins that is based on post-translational modifications? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:815–820. doi: 10.1038/nrm2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milne TA, et al. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura T, et al. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dou Y, et al. Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:713–719. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama A, Cleary ML. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hess JL. MLL: a histone methyltransferase disrupted in leukemia. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shih LY, et al. Characterization of fusion partner genes in 114 patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia and MLL rearrangement. Leukemia. 2006;20:218–223. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorrance AM, et al. The Mll partial tandem duplication: differential, tissue-specific activity in the presence or absence of the wild-type allele. Blood. 2008;112:2508–2511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dorrance AM, et al. Mll partial tandem duplication induces aberrant Hox expression in vivo via specific epigenetic alterations. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2707–2716. doi: 10.1172/JCI25546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroon E, et al. Hoxa9 transforms primary bone marrow cells through specific collaboration with Meis1a but not Pbx1b. Embo J. 1998;17:3714–3725. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Argiropoulos B, Humphries RK. Hox genes in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Oncogene. 2007;26:6766–6776. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slany RK. The molecular biology of mixed lineage leukemia. Haematologica. 2009;94:984–993. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okada Y, et al. hDOT1L links histone methylation to leukemogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okada Y, et al. Leukaemic transformation by CALM-AF10 involves upregulation of Hoxa5 by hDOT1L. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/ncb1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mueller D, et al. A role for the MLL fusion partner ENL in transcriptional elongation and chromatin modification. Blood. 2007;110:4445–4454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milne TA, Martin ME, Brock HW, Slany RK, Hess JL. Leukemogenic MLL fusion proteins bind across a broad region of the Hox a9 locus, promoting transcription and multiple histone modifications. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11367–11374. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krivtsov AV, et al. H3K79 methylation profiles define murine and human MLL-AF4 leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guenther MG, et al. Aberrant chromatin at genes encoding stem cell regulators in human mixed-lineage leukemia. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3403–3408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1741408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiel AT, et al. MLL-AF9-induced leukemogenesis requires coexpression of the wild-type Mll allele. Cancer Cell. 17:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steger DJ, et al. DOT1L/KMT4 recruitment and H3K79 methylation are ubiquitously coupled with gene transcription in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2825–2839. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02076-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulze JM, et al. Linking cell cycle to histone modifications: SBF and H2B monoubiquitination machinery and cell-cycle regulation of H3K79 dimethylation. Mol Cell. 2009;35:626–641. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellor J. Linking the cell cycle to histone modifications: Dot1, G1/S, and cycling K79me2. Mol Cell. 2009;35:729–730. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohan M, et al. Linking H3K79 trimethylation to Wnt signaling through a novel Dot1-containing complex (DotCom) Genes Dev. 24:574–589. doi: 10.1101/gad.1898410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bitoun E, Oliver PL, Davies KE. The mixed-lineage leukemia fusion partner AF4 stimulates RNA polymerase II transcriptional elongation and mediates coordinated chromatin remodeling. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:92–106. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park G, Gong Z, Chen J, Kim JE. Characterization of the DOT1L Network: Implications of Diverse Roles for DOT1L. Protein J. doi: 10.1007/s10930-010-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang W, Xia X, Reisenauer MR, Hemenway CS, Kone BC. Dot1a-AF9 complex mediates histone H3 Lys-79 hypermethylation and repression of ENaCalpha in an aldosterone-sensitive manner. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18059–18068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601903200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin C, et al. AFF4, a component of the ELL/P-TEFb elongation complex and a shared subunit of MLL chimeras, can link transcription elongation to leukemia. Mol Cell. 37:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mueller D, et al. Misguided transcriptional elongation causes mixed lineage leukemia. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung N, Chan LC, Thompson A, Cleary ML, So CW. Protein arginine-methyltransferase-dependent oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/ncb1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bracken AP, Helin K. Polycomb group proteins: navigators of lineage pathways led astray in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:773–784. doi: 10.1038/nrc2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gonzalez ME, et al. Downregulation of EZH2 decreases growth of estrogen receptor-negative invasive breast carcinoma and requires BRCA1. Oncogene. 2009;28:843–853. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu J, et al. Integrative genomics analysis reveals silencing of beta-adrenergic signaling by polycomb in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao Q, et al. Repression of E-cadherin by the polycomb group protein EZH2 in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:7274–7284. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kleer CG, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11606–11611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujii S, Ochiai A. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 downregulates E-cadherin by mediating histone H3 methylation in gastric cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:738–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang X, et al. CDKN1C (p57) is a direct target of EZH2 and suppressed by multiple epigenetic mechanisms in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ougolkov AV, Bilim VN, Billadeau DD. Regulation of pancreatic tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance by the histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homologue 2. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6790–6796. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morin RD, et al. Somatic mutations altering EZH2 (Tyr641) in follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of germinal-center origin. Nat Genet. 42:181–185. doi: 10.1038/ng.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiskus W, et al. Combined epigenetic therapy with the histone methyltransferase EZH2 inhibitor 3-deazaneplanocin A and the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat against human AML cells. Blood. 2009;114:2733–2743. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu S, Powers MA. Nuclear pore proteins and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:620–630. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cui K, et al. Chromatin signatures in multipotent human hematopoietic stem cells indicate the fate of bivalent genes during differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:80–93. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sykes DB, Kamps MP. E2a/Pbx1 induces the rapid proliferation of stem cell factor-dependent murine pro-T cells that cause acute T-lymphoid or myeloid leukemias in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1256–1269. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1256-1269.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pasini D, et al. Coordinated regulation of transcriptional repression by the RBP2 H3K4 demethylase and Polycomb-Repressive Complex 2. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.470008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coles AH, Jones SN. The ING gene family in the regulation of cell growth and tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:45–57. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ythier D, Larrieu D, Brambilla C, Brambilla E, Pedeux R. The new tumor suppressor genes ING: genomic structure and status in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1483–1490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Soliman MA, Riabowol K. After a decade of study-ING, a PHD for a versatile family of proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shah S, Smith H, Feng X, Rancourt DE, Riabowol K. ING function in apoptosis in diverse model systems. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:117–125. doi: 10.1139/O08-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pena PV, et al. Histone H3K4me3 binding is required for the DNA repair and apoptotic activities of ING1 tumor suppressor. J Mol Biol. 2008;380:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saksouk N, et al. HBO1 HAT complexes target chromatin throughout gene coding regions via multiple PHD finger interactions with histone H3 tail. Mol Cell. 2009;33:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hung T, et al. ING4 mediates crosstalk between histone H3 K4 trimethylation and H3 acetylation to attenuate cellular transformation. Mol Cell. 2009;33:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doyon Y, et al. ING tumor suppressor proteins are critical regulators of chromatin acetylation required for genome expression and perpetuation. Mol Cell. 2006;21:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coles AH, et al. p37Ing1b regulates B-cell proliferation and cooperates with p53 to suppress diffuse large B-cell lymphomagenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8705–8714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shiseki M, et al. p29ING4 and p28ING5 bind to p53 and p300, and enhance p53 activity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2373–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garkavtsev I, et al. The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control. Nature. 1998;391:295–298. doi: 10.1038/34675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garkavtsev I, Kazarov A, Gudkov A, Riabowol K. Suppression of the novel growth inhibitor p33ING1 promotes neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet. 1996;14:415–420. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jones DR, et al. Nuclear PtdIns5P as a transducer of stress signaling: an in vivo role for PIP4Kbeta. Mol Cell. 2006;23:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang W, et al. Stabilized phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate analogues as ligands for the nuclear protein ING2: chemistry, biology, and molecular modeling. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6498–6506. doi: 10.1021/ja070195b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chan DA, et al. Tumor vasculature is regulated by PHD2-mediated angiogenesis and bone marrow-derived cell recruitment. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jennes I, et al. Multiple osteochondromas: mutation update and description of the multiple osteochondromas mutation database (MOdb) Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1620–1627. doi: 10.1002/humu.21123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klaus A, Birchmeier W. Wnt signalling and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrc2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kramps T, et al. Wnt/wingless signaling requires BCL9/legless-mediated recruitment of pygopus to the nuclear beta-catenin-TCF complex. Cell. 2002;109:47–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fiedler M, et al. Decoding of methylated histone H3 tail by the Pygo-BCL9 Wnt signaling complex. Mol Cell. 2008;30:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gu B, et al. Pygo2 expands mammary progenitor cells by facilitating histone H3 K4 methylation. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:811–826. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Andrews PG, Lake BB, Popadiuk C, Kao KR. Requirement of Pygopus 2 in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kessler R, Hausmann G, Basler K. The PHD domain is required to link Drosophila Pygopus to Legless/beta-catenin and not to histone H3. Mech Dev. 2009;126:752–759. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamane K, et al. PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xiang Y, et al. JARID1B is a histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase up-regulated in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19226–19231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700735104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scibetta AG, et al. Functional analysis of the transcription repressor PLU-1/JARID1B. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7220–7235. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00274-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dalgliesh GL, et al. Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature. 463:360–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Bassermann F, Koyama-Nasu R, Pagano M. JHDM1B/FBXL10 is a nucleolar protein that represses transcription of ribosomal RNA genes. Nature. 2007;450:309–313. doi: 10.1038/nature06255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.He J, Kallin EM, Tsukada Y, Zhang Y. The H3K36 demethylase Jhdm1b/Kdm2b regulates cell proliferation and senescence through p15(Ink4b) Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1169–1175. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tzatsos A, Pfau R, Kampranis SC, Tsichlis PN. Ndy1/KDM2B immortalizes mouse embryonic fibroblasts by repressing the Ink4a/Arf locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pfau R, et al. Members of a family of JmjC domain-containing oncoproteins immortalize embryonic fibroblasts via a JmjC domain-dependent process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1907–1912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711865105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Haaften G, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:521–523. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barradas M, et al. Histone demethylase JMJD3 contributes to epigenetic control of INK4a/ARF by oncogenic RAS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1177–1182. doi: 10.1101/gad.511109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Agger K, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 contributes to the activation of the INK4A-ARF locus in response to oncogene- and stress-induced senescence. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1171–1176. doi: 10.1101/gad.510809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Agger K, et al. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]