Abstract

The Drosophila dorsal vessel is a beneficial model system for studying the regulation of early heart development. Spire (Spir), an actin-nucleation factor, regulates actin dynamics in many developmental processes, such as cell shape determination, intracellular transport, and locomotion. Through protein expression pattern analysis, we demonstrate that the absence of spir function affects cell division in Myocyte enhancer factor 2-, Tinman (Tin)-, Even-skipped- and Seven up (Svp)-positive heart cells. In addition, genetic interaction analysis shows that spir functionally interacts with Dorsocross, tin, and pannier to properly specify the cardiac fate. Furthermore, through visualization of double heterozygous embryos, we determines that spir cooperates with CycA for heart cell specification and division. Finally, when comparing the spir mutant phenotype with that of a CycA mutant, the results suggest that most Svp-positive progenitors in spir mutant embryos cannot undergo full cell division at cell cycle 15, and that Tin-positive progenitors are arrested at cell cycle 16 as double-nucleated cells. We conclude that Spir plays a crucial role in controlling dorsal vessel formation and has a function in cell division during heart tube morphogenesis.

Introduction

The Drosophila heart, also called the dorsal vessel, is a simple organ that acts as a myogenic pump to allow the circulation of hemolymph throughout the body. It is a proven model for studying cell-cell signaling and the regulation of early heart development. The dorsal vessel consists of 104 cardioblasts, which can be individually identified in vivo, such that differentiation and cell fate analysis can be conducted at the resolution of a single cell and followed throughout the whole developmental process [1]. Most segments of the dorsal vessel contain six pairs of cardioblasts: four pairs of Tinman (Tin)-positive cells that have large nuclei and two pairs of Seven up (Svp)-positive cells with smaller nuclei [2].

In the cardiogenic mesoderm, three transcriptional effectors, Tin, Pannier (Pnr) and Dorsocross (Doc), are essential for the generation of cardiac progenitors and cardioblast specification [3]. Mutations in any one of these genes cause severe defects in dorsal vessel formation. These three genes are activated by Decapentaplegic and Wingless signaling pathways and regulate each other. Subsequently these transcription factors, individually or in combination, activate known and yet to be discovered target genes that lead to the appropriate morphological structures of the dorsal vessel, as well as the proper differentiation of cardioblasts [2].

Cardiac progenitors arise from a discrete cell population that is generated during early embryonic mitosis. Three embryonic divisions (mitosis 14–16) are subsequent to interphase 14 in most cell lineages. The third division (mitosis 16) takes place during late stage 10 to stage 11 between 280–300 minutes after egg deposition. This division is characterized by a continuous longitudinal region that generates heart precursors and the development of a portion of the visceral mesoderm [4]. Cyclin A (CycA), which is the only cyclin necessary for mitosis in Drosophila, is found in the cytoplasm in interphase and accumulates in the nucleus during prophase [5], [6]. In addition, it was previously shown that CycA can compensate for Cyclin B in mitotic entry [7]. The last round of global cell division, mitosis 16, arrests in CycA mutants [7], [8].

Recently, several screens have been undertaken to identify new genes involved in cardiogenesis [9]. Through the use of a Df(3L)DocA mutant allele, previous studies have demonstrated that Doc interacts with tin, pnr and tailup (tup) [3], [10]. We completed a sensitized screen, using Df(3L)DocA as the background, to find genes that could potentially interact with Doc in heart development. Our screen identified spire (spir) as another Doc-interacting gene.

Spir is an actin-nucleation factor, which regulates actin dynamics in developmental processes such as cell shape determination, intracellular transport, and division [11], [12]. Spir protein orthologs from different species share a common structural array: a KIND domain at the N-terminus, a cluster of four Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-homology domain 2 (WH2) domains in the central region, and a Spir-Box and a FYVE membrane-binding domain at C-terminus [12]. The highly conserved WH2 domains are necessary and sufficient for the actin-nucleation activity of the protein [11].

Previous studies of Spir have focused on its function during Drosophila oogenesis, especially in domain interactions with Cappuccino [13]–[15]. In our current study, we demonstrate that Spir is ubiquitously expressed during embryogenesis and that cell division of Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (Mef2)-, Tin-, Even-skipped (Eve)- and Svp-positive heart cells are affected in the absence of spir. Furthermore through genetic analyses, we find that spir functionally interacts with Doc, tin, pnr and CycA to regulate cardiac fate and cell division. In addition, our results suggest that in spir mutant embryos, most Svp-positive progenitors fail to undergo full cell division at cell cycle 15. Tin-positive progenitors cannot divide at cycle 16 resulting in double-nucleated cells. Based on these findings, we believe that Spir plays a crucial role in cell division during heart tube morphogenesis and dorsal vessel formation.

Results

Spatial and temporal expression of Spir during embryogenesis

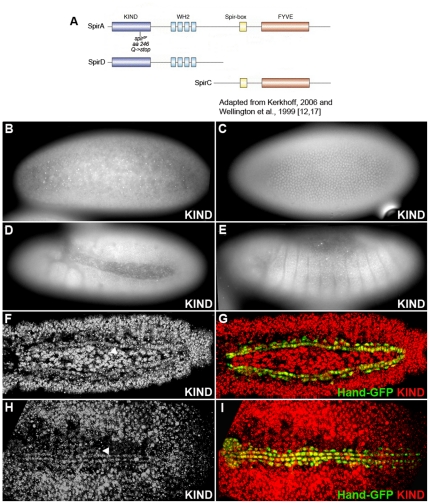

In Drosophila, several different Spir isoforms are encoded by the spir locus, three of which are well characterized: 1) the full-length Spir transcript, SpirA; 2) a splice variant that includes KIND and WH2 domain cluster, SpirD; and 3) a splice variant that includes the C-terminal region encoding the Spir-box and the FYVE zinc finger, SpirC.

Spir protein showed a ubiquitous expression pattern during embryogenesis (Fig. 1). Staining by anti-SpirC showed SpirC expressed in nuclei and cytoplasm ubiquitously (data not shown). An anti-KIND antibody recognizes the KIND domain at the N-terminus of the Spir protein and has been shown to accurately label SpirA and SpirD expression during Drosophila oogenesis [14]. An anti-SpirD antibody recognizes SpirD and the N-terminus of SpirA [16]. From early embryonic stages through stage 13, SpirA and SpirD were localized in nucleus and cytoplasm of every cell through anti-KIND and anti-SpirD staining (Fig. 1A–D). From stage 14 to 16, SpirA and D localization changed to be expressed in the nucleus of every cell (Fig. 1E, G). It was identified that at these stages when the heart cells were fully differentiated, both the KIND domain and SpirD co-localize with the heart specific cell marker, Hand-GFP, in the nuclei of both cardioblasts and pericardial cells (Fig. 1F, H). This indicates that Spir is expressed within the nuclei of heart cells at late embryonic stages.

Figure 1. Spir expression pattern during Drosophila embryogenesis.

(A) Diagram of SpirA, SpirC and SpirD proteins and the location of spir2F mutant. Anti-KIND antibody recognizes KIND domain in both SpirA and SpirD proteins. Anti-SpirD antibody recognizes SpirD and the N-terminus of the A-isoform. (B–I) Whole-mount antibody stainings of wild-type embryos with anti-KIND. Anti-SpirD antibody exhibits same staining pattern (data not shown). (B) Stage 4. (C) Stage 5. Focus on the lateral epidermis. (D) Stage 11. Fully extended germ band. (E) Stage 13 (lateral view). (F, G) Stage 15. Dorsal view to visualize the distinct accumulation of Spir in cardioblasts and pericardial cells. (H, I) Stage 16 (Dorsal view). Hand-GFP is expressed in cardioblasts, pericardial cells and the lymph gland. The Spir expression is co-localized with Hand-GFP in heart cells. Arrowheads point to cardioblasts.

Analysis of spir mutant phenotypes during heart development

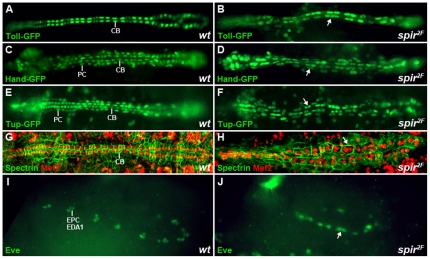

In order to assess spir function during heart development, various heart cell markers were used to analyze heart development in spir mutant embryos. In this study, we used a truncation mutant, spir2F, which has a stop-codon at amino acid 246, such that the protein does not include the four WH2 domains [17]. Initially, we used the transgenic GFP lines Hand-GFP and Tup-GFP, which mark cardioblasts and pericardial cells, and Toll-GFP, which marks cardioblasts and amnioserosa cells, to investigate the spir mutant phenotype in vivo. This allowed us to easily distinguish cells and count them accurately [18], [19]. In spir mutants, the nuclei of heart cells were elongated and slightly larger than those of normal heart cells (Fig. 2B, D, F). Additionally, these nuclei appeared in pairs within single cells as detected by a Spectrin antibody, which marks the membrane skeleton and allows clear visualization of the cell edge [20] (Fig. 2H). The average number of nuclei was 78±6 (n = 20). Based on the Spectrin staining, it was clear that in spir mutants, the size of the heart cells was much larger than that of normal heart cells, and that in most cells, there were two nuclei. This incomplete cell division resulted in a cardiac cell number much less than the normal 104 cells [2] (Fig. 2G, H).

Figure 2. Heart phenotypes in spir2F mutants.

(A–H) Compared to wild-type Drosophila embryos, spir2F mutant embryos are characterized by paired nuclei, larger cells and fewer cardioblasts at stage 16. (A, B) The Toll-GFP transgene expresses GFP in cardioblasts. (C, D) The Hand-GFP transgene and (E, F) the Tup-GFP transgene expresses GFP in cardioblasts, pericardial cells and the lymph gland. (G, H) Spectrin (green) and Mef2 (red) stain membrane skeleton and cardioblasts, respectively. (I, J) At stage 12, Eve stains pericardial cells and DA1 cells. In spir2F mutant embryos, Eve-positive cells appear in pairs. All embryos are oriented with the anterior to the left. All the images are taken under 40× magnification. Arrows indicate paired nuclei in spir mutants. Pericardial cells (PC), cardioblasts (CB), Eve-positive pericardial cells (EPC) and Eve-positive DA1 cells (EDA1) of the normal dorsal vessel are indicated in the wild-type embryos.

To determine if spir affected early heart development, embryos were stained with anti-Eve antibody. In stage 12 wild-type embryos, Eve progenitor cells differentiate into the Eve-positive pericardial cells and DA1 muscle cells of each hemi-segment, which appear in 2–3 cell clusters (Fig. 2I). In spir mutant embryos, there were no cell clusters, but the nuclei were in pairs (Fig. 2J). Finally, we analyzed the pattern of Svp- and Tin-positive heart cells by Svp-lacZ and Mef2 staining. The svp gene is the Drosophila homolog of the vertebrate COUP-TF nuclear transcription factor, a key regulator expressed in the non-Tin-expressing cardioblasts which represses tin expression in those cardioblasts [21]. In wild-type animals, Mef2 is expressed in all cardioblasts and within each heart segment there are two pairs of Svp-positive cardioblasts and four pairs of Tin-positive (Fig. 3C′, E). Compared to 14 pairs of Svp-positive cardioblasts in the normal heart, in spir mutants there were only an average of 12±4 Svp-positive cardioblast nuclei (n = 20; Fig. 3B′, D′, F, H). Together, these results suggest an important role for spir in proper cell division and specification including Mef2-, Tin-, Svp-, Eve-, Hand- and Tup-positive heart cells. In spir mutants, the division of the muscle cells were also abnormal as marked by Mef2 antibody and Tup-GFP indicating that it possibly functions widely in cell division during embryogenesis. However, this study specifically focused on spir function in heart development.

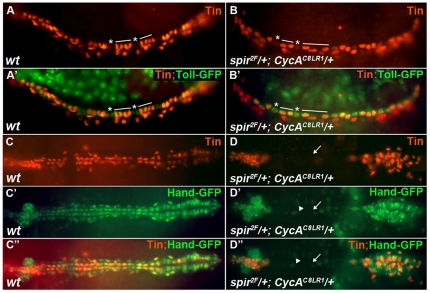

Figure 3. Pattern of Tin- and Svp-positive cells in wt, CycAC8LR1 and spir2F embryos.

(A, A′, B and B′) Lateral view at stage 13. (C, C′, D and D′) Dorsal view at stage 15. (E–H) Dorsal view at stage 16. Mef2 (red) stains Mef2-positive cardioblasts and β-Gal (green) stains Svp-positive cardioblasts. In spir2F mutants, when two nuclei appear together, most cells express only Svp. When three or four nuclei appear together, they are stained with both anti- β-Gal and anti-Mef2. SC, Svp-positive cardioblasts; TC, Tin-positive cardioblasts. Arrows point to Svp-positive cardioblasts; Arrowheads point to Svp-positive pericardial cells. * indicates Svp-positive cells; — indicates Tin-positive cells.

In order to study which stage of the cell cycle was affected by the spir mutation, we compared the expression pattern of Svp and Tin in spir mutants to that of CycA mutants, which causes cell cycle arrest at mitosis 16 [7]. It has been found that in CycA mutants, the number of Mef2-positive cardioblasts is reduced from six to four per hemi-segment, consisting of two Tin-positive cells and two Svp-positive cells, with one nucleus per cell (Fig. 3G) [22]. In contrast to wild-type and CycA mutants, spir mutants showed that in cells with 3 or 4 nuclei together, the nuclei were stained by both anti-Svp and anti-Mef2 antibodies, which suggested that they were Svp-positive cardioblasts. However, cells with paired nuclei that expressed only Svp, and not Mef2, were Svp-positive pericardial cells (n>50 spir mutant embryos) (Fig. 3B′, D′, F, H). This investigation suggests that Spir affects the fate of Svp-positive progenitors.

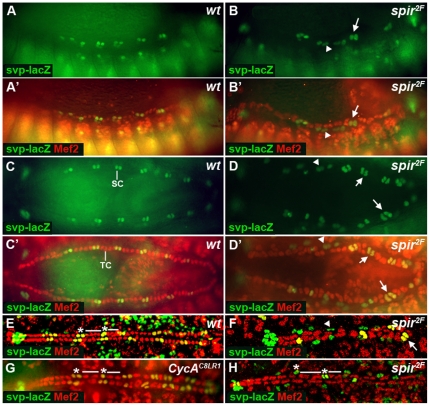

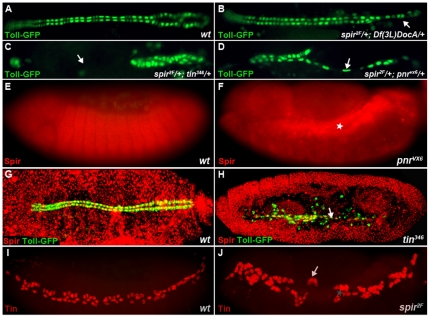

spir interacts with tin, pnr and Doc during cardiogenesis

Doc, Tin, and Pnr are essential transcription factors, known to regulate each other and function in the specification of cardioblasts [3]. We tested double heterozygous mutant embryos: spir2F/+; Df(3L)DocA/+, spir2F/+; tin346/+, and spir2F/+; pnrVX6/+, to determine the interaction between spir and each of these factors, respectively. The phenotypes of these double heterozygous embryos were compared with the phenotypes of single heterozygous embryos for each of the investigated alleles. Although most embryos had normal numbers of cardioblasts, a small fraction of single heterozygous spir2F, Df(3L)DocA, tin346, and pnrVX6 embryos presented with reduced numbers of cardioblasts, indicating that the decreased activity of these genes inhibited normal cardioblast development (data not shown). However, in all groups, the ratio of the number of mutant hearts to normal hearts was significantly different when comparing single heterozygous and double heterozygous embryos (Table 1). When spir2F was combined with either tin346 or pnrVX6, the double heterozygous embryos showed obvious gaps within the Toll-GFP myocardial cell rows in ∼20% of the embryos analyzed. When combined with Df(3L)DocA, this percentage was approximately 10% (Fig. 4B–D, Table 1). Interestingly, in spir and pnr double heterozygous embryos, there were elongated nuclei similar to those in spir mutants. A Chi-square test showed that the interactions between spir and pnr, spir and tin were stronger than the interaction between spir and Doc, as indicated by the p value (Ppnr<0.0001; Ptin<0.0001; PDoc = 0.06, Table 1). This analysis indicates that spir is required in combination with tin, pnr and Doc to properly specify cardioblasts.

Table 1. Statistical analysis of genetic interaction between spir and tin, spir and Doc, spir and pnr, spir and CycA.

| Genotype | Normal hearts | Mutant hearts | % | Genotype | Normal hearts | Mutant hearts | % |

| spir2F/+; tin346/+ | 153 | 43# | 22% | spir2F/+; Df(3L)DocA/+ | 217 | 23# | 10% |

| tin346/+ | 249 | 30 | 11% | Df(3L)DocA/+ | 249 | 14 | 5% |

| spir2F/+ | 257 | 13 | 5% | spir2F/+ | 257 | 13 | 5% |

| P value | Ptin<0.0001** | PDoc = 0.06* | |||||

| spir2F/+; pnrvx6/+ | 134 | 41# | 23% | spir2F/+; CycAC8LR1/+ | 76 | 43 | 36% |

| pnrvx6/+ | 136 | 13 | 9% | CycAC8LR1/+ | 297 | 10 | 3% |

| spir2F/+ | 257 | 13 | 5% | spir2F/+ | 257 | 13 | 5% |

| P value | Ppnr<0.0001** | PCycA<0.0001** |

**The χ2 test reveals in all three groups that the proportion of mutant and normal embryos is statistically different for single heterozygous and double heterozygous embryos.

*The χ2 statistic is not significant at the 0.05 level, but at the 0.1 level.

Mutant hearts in these double heterozygotes denote gap phenotype.

Figure 4. Genetic interactions between spir and Doc, tin, pnr.

(A) Wild-type embryo. (B–D) Double heterozyous embryos of spir and Df(3L)DocA, spir and tin and spir and pnr, respectively. Embryos are all at stage 16. The mutant phenotypes of all three double heterozygous embryos show missing cardioblasts. (E–H) Spir antibody staining in wt and pnr mutant, wt and tin mutant embryos, respectively. (E, F) In pnr mutant embryos, Spir is over-expressed in the cardiac mesoderm, compared to the ubiquitous expression pattern in wild-type embryo at stage 13. (G, H) There is no Spir expression in heart cells in tin mutants at stage 16. The cells that express Toll-GFP and Spir are amnioserosa cells. (I, J) Tin antibody staining in wild-type embryo (I) and spir mutant embryo (J) at stage 13. Tin cells appear in pairs and are disorganized. Arrows highlight the abnormal positioning of cardioblasts in different mutant embryos. ★ indicates cardiac mesoderm.

To further evaluate the functional relationships between spir and tin, pnr and Doc, we analyzed the expression of Spir in Df(3L)DocA, pnrVX6 and tin346 mutant embryos. Staining of Spir protein in Df(3L)DocA embryos showed that Spir was expressed ubiquitously (data not shown). In half of pnr mutant embryos, Spir was over-expressed in cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 4F). In tin346 mutant embryos, Spir staining was absent in cardioblasts because as a consequence of the mutation, no heart cells were found (Fig. 4H).

spir2F mutant embryos were also stained with anti-Tin, anti-Pnr and anti-Doc antibodies. At stage 11, Tin, Pnr and Doc are all expressed in cardiac mesoderm in the Drosophila embryo [3]. Later in development, tin expression continues in a certain set of cardioblasts and pericardial cells [20], [23], [24]. The expressions of Doc and Pnr cease during stages 12 and 13. However, Doc expression is weakly maintained in Svp-expressing cardioblasts until the end of embryogenesis [21], [25]. At stage 13 in spir2F mutants, Tin stained nuclei were close together and appeared in pairs. This result reaffirmed previous findings suggesting defects in Tin-positive cardiac precursor cell division (Fig. 4J). However, the Pnr and Doc expression patterns were unchanged in spir2F mutant embryos at stage 13 (data not shown). Our results, combined with the data above, suggest that spir genetically interacts with tin, Doc, and pnr to different degrees to regulate heart cell division.

spir interacts with CycA during dorsal vessel formation

We next investigated a possible genetic interaction between CycA and spir. In CycA and spir double heterozygous embryos, 35% of the embryos showed either abnormal cell division or a significant loss of heart cells, especially in the aorta region of the heart tube (Fig. 5B, D). Some double heterozygous embryos showed that the Tin- and Svp-positive cell divisions were both affected by the double heterozygous mutations. For example, some double heterozygous mutants formed two Tin-positive cells and one Svp-positive cell in each hemi-segment (Fig. 5B, B′). When compared to the CycA mutant phenotype, one Svp-positive cell was missing in each hemi-segment of the double heterozygotes. In contrast to the spir mutants, there were no paired nuclei in the double heterozygous embryos. This result suggests that spir interacts with CycA and leads to the abnormal cell division from both Tin- and Svp-positive super-progenitors (preprogenitors) to progenitors (cycle 15) as indicated by our model discussed later. Other double heterozygous embryos showed large gaps formed in the heart tube due to loss of many heart cells, indicating that there were no precursor cells formed which resulted in the absence of cardioblasts at the later stages (Fig. 5D–D″). Chi-square analysis also demonstrated that the combined action of spir and CycA was required for proper cardiac cell division (PCycA<0.0001, Table 1).

Figure 5. Genetic interaction between spir and CycA.

This interaction results in various phenotypes. (A, A′, B and B′) Stage 13. In each hemi-segment, there are two Tin-positive cells and one Svp-positive cell in spir and CycA double heterozygous embryos (B and B′). (C–C″ and D–D″) Stage 16. Many cells are missing in the aorta region (D–D″). Many mutant embryos show a phenotype between these two extremes. Arrows emphasize cellular gaps in the dorsal vessel. * indicates Svp-positive cells; — indicates Tin-positive cells. Arrowheads point to paired nuclei. Arrows point to the missing cells.

Discussion

Cardiac cell fate specification requires the coordinated function of multiple factors such as tin, pnr, and Doc. Drosophila is an ideal model for the determination of the complex transcriptional network that initiates and maintains the cardiac lineage. Our data place the nucleation factor spir as an integral factor in cardiac cell division and dorsal vessel formation.

Proper dorsal vessel morphogenesis is critically dependent upon intercellular signaling and the regulation of gene expression. Although great progress has been made in the study of heart development, it is not known exactly how many genes and pathways are involved in this cardiogenic process or how many of these factors cooperate together. Previous genetic screens have identified genes that play roles in the specification, morphogenesis, and differentiation of the heart, including mastermind and tup [10], [26], [27]. Our sensitized screen has also been proved as an efficient method to find additional factors in this process, suggesting that much remains to be learned about the molecular components involved in correct dorsal vessel formation.

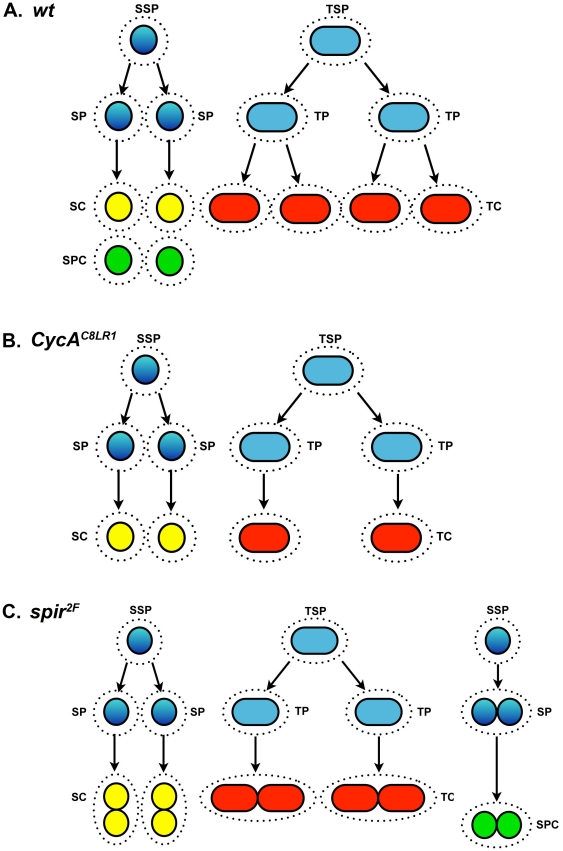

Spir is required for the proper timing of cytoplasmic streaming in Drosophila, and loss of spir leads to premature microtubule-dependent fast cytoplasmic streaming during oogenesis, the loss of oocyte polarity, and female sterility [28]. Even though it is known that spir is an important actin filament nucleation factor, our findings are the first report to describe a function of spir for cell division. Through phenotypic analysis of the spir mutant phenotype, we find that many cardioblast nuclei are partially or completely divided. However, the cytoplasm is not divided in the absence of spir, which is consistent with the function of spir in cytoplasmic movement. Thirteen rapid nuclear division cycles without cell division initiate Drosophila embryo development, followed by three waves of cell division [29]–[31]. The first wave of cell division occurs in the mesoderm at cell cycle 14. After this initial division, cells migrate, spread dorsally and undergo a second round of cell division at cell cycle 15. The third wave of cell division in the mesoderm occurs at the end of germband extension during cell cycle 16. There are two different types of cardioblast precursor cells: one type divides into two identical Tin-positive cardioblasts (TC), and the other type divides into one Svp-positive cardioblast (SC) and one Svp-positive pericardial cell (SPC) [24]. Based on the comparison of CycA and spir mutant phenotypes, we predict a tentative cell division model to demonstrate spir function in determining cardiac cell fate (Fig. 6). Han and Bodmer [22] demonstrate that in a wild-type background, one Svp-positive super progenitor (SSP) divides into two Svp-positive progenitors (SP), then each of these cells divides into one SPC and one SC. For Tin-positive super progenitors (TSP), after each divides into two Tin-positive progenitors (TP), each TP further divides into two identical TCs (Fig. 6A). In our model, division from the super progenitor to progenitors takes place at cell cycle 15, and division from progenitors to full differentiated heart cells occurs at cell cycle 16. In CycA mutants, mitosis 16 is blocked such that both SPs and TPs stop cell division. This results in the two SPs assuming a myocardial fate. Thus the number of SCs remains normal, but half of the TCs are missing in the CycA mutants [22] (Fig. 6B). Our data suggest that in spir mutant embryos, most of the SPs fail to undergo full cell division at cycle 15 resulting in a SPC fate with paired nuclei. A subset of these cells are able to undergo the 15th cell division but are arrested at cycle 16 as double-nucleated cells which exhibit both Svp and Mef2 staining, characteristic of the SCs seen in the CycA mutants. Similarly, for TPs, cycle 16 was also blocked such that it resulted in two double-nucleated cells. In summary, Spir affects mitosis 16 for Tin-positive cell division and both mitosis 15 and 16 for Svp-positive cell division (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. A cell division model of spir function during heart development.

(A) In wild-type embryos, there are six cardioblasts in each hemi-segment including two Svp-positive and four Tin-positive cells. An SSP divides into two SPs, then each of the SPs divides into one SC and one SPC. After two cell cycles, one TSP differentiates into 4 TCs. (B) In CycA mutants, cell cycle 16 is blocked so that there are two SCs and two TCs in each hemi-segment. However, there are no SPCs. (C) In spir mutants, the nucleus duplicates and divides while the cytoplasm does not. Most of the SSPs stop division at cell cycle 15 resulting in double-nucleated cells. Some of the SSPs divide into two SPs, but stop at cell cycle 16 giving rise to four or three nuclei clusters. TPs are arrested at cell cycle 16 leading to two double-nucleated cells in each hemi-segment. SSP, Svp-positive super-progenitor; TSP, Tin-positive super-progenitor; SP, Svp-positive progenitor; TP, Tin-positive progenitor; SC, Svp-positive cardioblasts; TC, Tin-positive cardioblast; SPC, Svp-positive pericardial cells. The dotted circle represents the cell membrane.

Antibody staining implicates that Spir is expressed ubiquitously before stages 12–13 and is located in both nuclei and cytoplasm. After cell cycle 16 cell division stops, occurring during stage 10–11. The expression of Spir in the cytoplasm then decreases gradually. At stage 15, the staining pattern shows mostly nucleus expression with some cytoplasmic expression and by stage 16 the nuclei become distinct indicating nucleus staining only. It is hypothesized that expression of Spir decreases in the cytoplasm but remains constant in the nuclei when cell division halts.

Our genetic analysis of spir, Doc, pnr and tin suggests that these factors may regulate each other during dorsal vessel formation, and especially significant is the interaction between spir and pnr. Pnr is a GATA class transcription factor expressed in both the dorsal ectoderm and dorsal mesoderm, where it is required for cardiac cell specification. Proper dorsal vessel formation is inhibited in pnr loss-of-function embryos due to failure in the specification of the cardiac progenitors [32]–[34]. In spir mutants, the expression pattern of Pnr remains normal. However, Spir is over expressed in the cardiac mesoderm in pnr mutants, suggesting that Pnr may repress the expression of the spir.

In conclusion, Spir is a newly-identified factor functioning in cell division during dorsal vessel formation. Tin-, Eve- and Svp-positive heart cells are all affected in the absence of spir. Also, spir expression depends on the transcription factors Doc, tin and pnr. Genetic interaction data also show that spir cooperates with CycA in heart cell division.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila strains and genetics

The following mutant fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center: spir2F, spir1, pnrVX6, CycAC8LR1, Svp-lacZ/TM3, w; nocsco/CyO, P{Dfd-EYFP}2, w; ry506 Dr1/TM6B, P {Dfd-EYFP} 3, Sb1 Tb1 ca1, w; In(2LR)noc4LScorv9R, b1/CyO, P{ActGFP}JMR1. Df(3L)DocA [25] and tin346 [35] were obtained from Dr. M. Frasch (Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany). The Hand-GFP transgenic stock was obtained from Dr. Z. Han (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI). The Toll-GFP and Tup-GFP transgenic reporters were maintained by our lab [18], [27].

The pnrVX6, tin346 and Df(3L)DocA were rebalanced with TM6B, P{Dfd-EYFP}3 and combined with Toll-GFP on the X chromosome. The spir2F was rebalanced with CyO, P{Dfd-EYFP}2. This Dfd-EYFP driven by deformed enhancer can score mid- to late-stage embryos, which facilitates phenotype analysis. For the genetic interaction analysis, embryos not expressing Dfd-EYFP were selected and analyzed.

Screen Strategy

On the basis of Rein's work [3] and our own experiments, a sensitized screen was conducted by crossing deficient second chromosome stocks with Df(3L)DocA flies. Each deficiency stock was crossed to the strain that carried an embryonic marker in the second chromosome balancer. Progeny with both the heterozygous mutant allele and embryonic marker were collected and crossed to deficient DocA, with Dfd-EYFP in the balancer, and Toll-GFP on X chromosome. Embryos from the second cross were checked under the fluorescence microscope. Double heterozygous embryos with both the deleted region and deleted Doc genes were separated by their lack of Dfd-EYFP. Embryos were gathered and screened 6–10 times, totally approximately 200 embryos checked per cross.

The Chi-square test indicated that if 20 mutant hearts out of a total of 200 embryos was indicative of a statistically significant difference between double heterozygous embryos and single heterozygous embryos (p<0.1). This percentage was derived from a control using wild-type heterozygous Df(3L)DocA embryos where there were 14 mutant hearts in 263 embryos. The final step of the screen was to narrow down the relevant regions which had statistically good mutant percentages, in order to find genes within those regions that can function in coordination with Doc. Embryos that were homozygous for the mutant allele were assessed for dorsal vessel phenotypes in the following ways: (1) evaluation of cardioblast assembly during the development of the dorsal vessel; (2) verification that the cardioblasts were properly ordered into two parallel rows of adjoining cells; (3) confirmation that each of the 104 cardioblasts normally present in a phenotypically wild-type dorsal vessel was present and properly specified; and finally (4) assessment of the ability of the cardioblast rows to migrate along the ectoderm as the dorsal vessel closes.

Immunohistochemistry

Various single- and double-label immunohistochemistry analyses were performed as previously described [18]. The following primary antibodies were used in these studies: mouse anti-β-galactosidase, 1∶300 (Promega, Madison, WI); rabbit anti-Mef2, 1∶1,000 (H. Nguyen); mouse anti-α-Spectrin, 1∶200 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank); rabbit anti-Tin, 1∶750; rabbit anti-Doc2, 1∶2000 and rabbit anti-Pnr, 1∶3000 (M. Frasch) [3]; rabbit anti-Eve, a 1∶2000 dilution (J. Skeath); rabbit anti-Spir KIND, 1∶200 (E. Kerkhoff). A mouse anti-SpirD antibody (1∶100 dilution) was used to detect the D-isoform or N-terminus of the A-isoform, while a mouse anti-SpirC3 antibody (1∶100 dilution) was used to detect the C-isoform or the C-terminus of the A-isoform (S.M. Parkhurst) [16]. These Spir antibodies were used to determine the localization of endogenous Spir in wild-type Drosophila embryos through immunofluorescence staining. Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa Flour 488 goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse (1∶400), and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit (1∶400) (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope and a Nikon A1R laser scanning confocal microscope.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for stocks obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. We thank Drs. M. Frasch, J.B. Skeath, E. Kerkhoff, M.E. Quinlan and S.M. Parkhurst for providing reagents. This work was facilitated through the use of the Notre Dame Integrated Imaging Facility.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant to R.A.S. from the National Institutes of Health (HL059151) and a Postdoctoral Fellow Award to P.X. from the American Heart Association (10POST2630076). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Medioni C, Sénatore S, Salmand PA, Lalevée N, Perrin L, et al. The fabulous destiny of the Drosophila heart. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao Y, Schulz RA. Heart development in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reim I, Frasch M. The Dorsocross T-box genes are key components of the regulatory network controlling early cardiogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:4911–4925. doi: 10.1242/dev.02077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campos-Ortega JA, Hartenstein V. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. 2nd edn. Berlin: Spinger-Verlag; 1997. pp. 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs HW, Knoblich JA, Lehner CF. Drosophila Cyclin B3 is required for female fertility and is dispensable for mitosis like Cyclin B. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3741–3751. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehner CF, O'Farrell PH. Expression and function of Drosophila cyclin A during embryonic cell cycle progression. Cell. 1989;56:957–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knoblich JA, Lehner CF. Synergistic action of Drosophila cyclins A and B during the G2-M transition. EMBO J. 1993;12:65–74. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong X, Zavitz KH, Thomas BJ, Lin M, Campbell S, et al. Control of G1 in the developing Drosophila eye: rca1 regulates Cyclin A. Genes Dev. 1997;11:94–105. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reim I, Frasch M. Genetic and genomic dissection of cardiogenesis in the Drosophila model. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann T, Bodmer R, Pandur P. The Drosophila homolog of vertebrate Islet1 is a key component in early cardiogenesis. Development. 2009;136:317–326. doi: 10.1242/dev.022533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinlan ME, Heuser JE, Kerkhoff E, Mullins RD. Drosophila Spire is an actin nucleation factor. Nature. 2005;433:382–388. doi: 10.1038/nature03241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerkhoff E. Cellular functions of the Spir actin-nucleation factors. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosales-Nieves AE, Johndrow JE, Keller LC, Magie CR, Pinto-Santini DM, et al. Coordination of microtubule and microfilament dynamics by Drosophila Rho1, Spire and Cappuccino. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:367–376. doi: 10.1038/ncb1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinlan ME, Hilgert S, Bedrossian A, Mullins RD, Kerkhoff E. Regulatory interactions between two actin nucleators, Spire and Cappuccino. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:117–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumacher N, Borawski JM, Leberfinger CB, Gessler M, Kerkhoff E. Overlapping expression pattern of the actin organizers Spir-1 and formin-2 in the developing mouse nervous system and the adult brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu R, Abreu-Blanco MT, Barry KC, Linardopoulou EV, Osborn GE, et al. Wash functions downstream of Rho and links linear and branched actin nucleation factors. Development. 2009;136:2849–2860. doi: 10.1242/dev.035246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wellington A, Emmons S, James B, Calley J, Grover M, et al. Spire contains actin binding domains and is related to ascidian posterior end mark-5. Development. 1999;126:5267–5274. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Tao Y, Reim I, Gajewski K, Frasch M, et al. Expression, regulation, and requirement of the Toll transmembrane protein during dorsal vessel formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4200–4210. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4200-4210.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han Z, Yi P, Li X, Olson EN. Hand, an evolutionarily conserved bHLH transcription factor required for Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development. 2006;133:1175–1182. doi: 10.1242/dev.02285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JK, Coyne RS, Dubreuil RR, Goldstein LS, Branton D. Cell shape and interaction defects in α-spectrin mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 1993;1123:1797–1809. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lo PC, Frasch M. A role for the COUP-TF-related gene seven-up in the diversification of cardioblast identities in the dorsal vessel of Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2001;104:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han Z, Bodmer R. Myogenic cells fates are antagonized by Notch only in asymmetric lineages of the Drosophila heart, with or without cell division. Development. 2003;130:3039–3051. doi: 10.1242/dev.00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin Z, Frasch M. Regulation and function of tinman during dorsal mesoderm induction and heart specification in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1998;22:187–200. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:3<187::AID-DVG2>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward EJ, Skeath JB. Characterization of a novel subset of cardiac cells and their progenitors in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2000;127:4959–4969. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.22.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reim I, Lee HH, Frasch M. The T-box-encoding Dorsocross genes function in amnioserosa development and the patterning of the dorsolateral germ band downstream of Dpp. Development. 2003;130:3187–3204. doi: 10.1242/dev.00548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tao Y, Christiansen AE, Schulz RA. Second chromosome genes required for heart development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genesis. 2007;45:607–617. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao Y, Wang J, Tokusumi T, Gajewski K, Schulz RA. Requirement of the LIM homeodomain transcription factor Tailup for normal heart and hematopoietic organ formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3962–3969. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00093-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theurkauf WE. Premature microtubule-dependent cytoplasmic streaming in cappuccino and spire mutant oocytes. Science. 1994;265:2093–2096. doi: 10.1126/science.8091233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Farrell PH, Edgar BA, Lakich D, Lehner CF. Directing cell division during development. Science. 1989;246:635–640. doi: 10.1126/science.2683080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foe VE, Alberts BM. Studies of nuclear and cytoplasmic behaviour during the five mitotic cycles that precede gastrulation in Drosophila embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1983;61:31–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foe VE. Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1989;107:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gajewski K, Fossett N, Molkentin JD, Schulz RA. The zinc finger proteins Pannier and GATA4 function as cardiogenic factors in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:5679–5688. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvarez AD, Shi W, Wilson BA, Skeath JB. pannier and pointedP2 act sequentially to regulate Drosophila heart development. Development. 2003;130:3015–3026. doi: 10.1242/dev.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klinedinst SL, Bodmer R. Gata factor Pannier is require to establish competence for heart progenitor formation. Devlopment. 2003;130:3027–3038. doi: 10.1242/dev.00517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azpiazu N, Frasch M. tinman and bagpipe: two homeo box genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]