Abstract

A novel hierarchical quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping method using a polynomial growth function and a multiple-QTL model (with no dependence in time) in a multitrait framework is presented. The method considers a population-based sample where individuals have been phenotyped (over time) with respect to some dynamic trait and genotyped at a given set of loci. A specific feature of the proposed approach is that, instead of an average functional curve, each individual has its own functional curve. Moreover, each QTL can modify the dynamic characteristics of the trait value of an individual through its influence on one or more growth curve parameters. Apparent advantages of the approach include: (1) assumption of time-independent QTL and environmental effects, (2) alleviating the necessity for an autoregressive covariance structure for residuals and (3) the flexibility to use variable selection methods. As a by-product of the method, heritabilities and genetic correlations can also be estimated for individual growth curve parameters, which are considered as latent traits. For selecting trait-associated loci in the model, we use a modified version of the well-known Bayesian adaptive shrinkage technique. We illustrate our approach by analysing a sub sample of 500 individuals from the simulated QTLMAS 2009 data set, as well as simulation replicates and a real Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) data set, using temporal measurements of height as dynamic trait of interest.

Keywords: functional mapping, scots pine, QTL, multitrait, Bayesian model, MCMC

Introduction

Several approaches to mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) influencing dynamic traits (that is, traits, of which expression changes over time) have been proposed (see Wu and Lin, 2006 for a review). Even though phenotypes measured at different time points may be controlled by different sets of QTLs, the phenotypic values over time points are generally highly correlated. Thus, the repeated measurement framework has been proposed for QTL analysis of trait measurements over time (Lynch and Walsh, 1998). Alternatively, traits measured at different time points can be treated as separate traits and analysed jointly in a multitrait framework. Here, the efficient parametrisation of multiple trait framework in terms of covariance functions provides a viable approach (Macgregor et al., 2005; Lund et al., 2008). However, the most common practice is to use some mathematical function to describe dynamic trait behaviour and then map QTLs, which influence this special function using single or multivariate QTL mapping. For example, the logistic growth function (Ma et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2002, 2003, 2004), as well as polynomial functions (that is, multiple regression model) (Gee et al., 2003), and Legendre polynomial (Yang et al., 2006; Yang and Xu, 2007) have been proposed for this purpose. The logistic growth function has been justified biologically (West et al., 2001). As a criticism, regression using logistic functions fit only growth trajectories that are sigmoidal, that is, monotonically increasing function of time (Yang and Xu, 2007). The Legendre and other orthogonal polynomial fittings (for covariance function) have also been criticised by Pletcher and Geyer (1999). In general, the choice of function should be based on the complexity of the trait trajectory. Even if several methods have been proposed, most of the approaches are limited to single or two-QTL model. Exceptions to this include the methods of Yang and Xu (2007), Min et al., 2011, and Heuven and Janss (2010).

Separate age-to-age analysis of QTL for growth has been applied to address questions on QTL stability across time in woody trees (Verhaegen et al., 1997; Conner et al., 1998; Kaya et al., 1999; Lerceteau et al., 2001). However, to our knowledge, Ma et al. (2004) is the only study where functional QTL mapping has been applied to study growth trajectories in a forest tree species. In their work, Ma et al. (2004) noted an increased statistical power for QTL detection based on a functional mapping method compared with the alternative QTL time-point analysis.

Functional QTL mapping methods commonly model average curve behaviour with time-specific QTL and environmental effects (Yang and Xu, 2007 and Min et al., 2011). Individual-specific variations in these methods are described as deviations from the mean curve behaviour, and these deviations are dependent at neighbouring time points. Exceptions to this common theme are provided by Gee et al. (2003) and Heuven and Janss (2010), where all time-dependent behaviour is described with individual-specific curve parameters, which allows hierarchical modeling of QTL effects. These two worlds (hierarchical and non-hierarchical) are conceptually very distinct from each another. In the parametrisation of Gee et al. (2003), QTL effects are not time dependent and they affect the shape of the curve rather than having specific effect at particular time points. To describe the functional curve over time, we consider here the approach of Gee et al. (2003). As an improvement to their approach (as well as to the approach of Heuven and Janss, 2010), we formulate the whole problem as a single hierarchical model. In our formulation, we simultaneously use multitrait multiple-QTL model and model selection, while estimating functional curve and other model parameters in a Bayesian framework.

Model

Let us consider the population-based sample of individuals where the data sample has been phenotyped with respect to some dynamic trait, and genotyped at a given set of marker loci. Although this represents a typical design in the population-based single-nucleotide polymorphism association studies, the proposed method is directly applicable to a backcross and double haploids in inbred lines, as well as offspring population resulting from outbred line crosses. When handling missing values, we ignore parental (linkage) information completely, so that markers are treated independently. This also means that only marker positions are considered as putative QTL positions. For alternatives, see the subsection dealing with Missing genotype data further on.

Phenotypic model over time points

For each individual i, let us assume that yi,t is the phenotypic value measured at time point t, (t=1,…,T). We use the following regression model to describe the phenotypic behaviour over time:

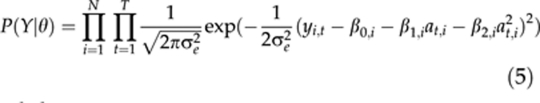

Here, βi={β0,i,β1,i,β2,i} are the curve parameters for individual i, and the errors ei,t are assumed to be independent and normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ2e common for all time points. Because the curve parameters are different across individuals, we pre-specify σ2e to improve parameter identifiability in our hierarchical model (described below). Note that σ2e describes how much measurements at each time-point are allowed to deviate from individual-specific curve (that is, the level of agreement between the data and the growth function). The suitable value for σ2e will depend on the type of the data. For example, for growth data, we have used here σ2e=0.1 constantly in our small simulation examples and σ2e=0.01 for real data analyses and for QTLMAS 2009 data analysis (the selected value of σ2e should not be too large as this may lead to all the QTL variation being erroneously explained by the residual error). The quantity at,i is the age of individual i at timepoint t (in calendar time which can be expressed as deviation from the mean age; see Gee et al., 2003). For simplicity we consider common time points and same age for all individuals so that at,i=t for time-points t=1,…,T, and all i.

Multiple trait QTL model

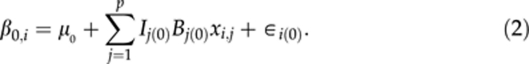

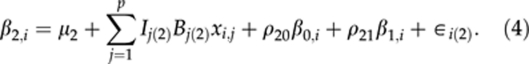

We treat the three curve parameters in βi as three latent traits, and assume that, conditionally on genetic effects, the curve parameters are a priori correlated with each other. By making such an assumption, we can hierarchically fit a multitrait QTL model for the curve parameters βi. For each individual i, let us assume that there are p additively acting marker loci with genotypic values xi,j, j=1,…,p, coded as 0 or 1 for two homozygotes and the 0.5 for the heterozygote. Given the marker effects (B(k)={B1(k),…,Bp(k)}, k=0, 1, 2), each curve parameter (βk,i, k=0, 1, 2) is modelled as a linear combination (weighted sum) of effects of genotypes xi,j at different loci.

|

|

|

Here, μ={μ0,μ1,μ2} are the baseline parameters, and ∈i(k) are the residuals. Residuals ∈i(k) are assumed to be independent and identically normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ2∈(k) Different residual variances are represented in the vector σ2∈={σ2∈(0),σ2∈(1),σ2∈(2)}. The autoregressive terms ρ={ρ10,ρ20, and ρ21} are included in the model to take into account between-trait residual dependencies so that actual residuals can be assumed to be independent. Autoregressive models are usually used to model covariances between different time points in time series data. We use the same principle here to model between trait covariances (cf class D model of Bonney, 1986). Note that even if one-directional dependence is visible in the model, two-way dependence will be induced automatically as β0,i and β1,i are model parameters rather than observed quantities in the model. Although a model assuming multivariate normally distributed residuals with unstructured covariance matrix would have been a common way to model this phenomenon, we decided to use this autoregressive model on computational grounds.

In the above multiple trait QTL model, we use own indicator variable for each locus and for each trait, Ij(k), where k=0,1 or 2. Although these indicators provide a natural way to monitor posterior occupancy of QTLs, the real reason for having them in the model is to improve heritability estimation as shown by Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää (2009). For details, see the subsection dealing with Heritabilities and genetic covariances/correlations.

Although not explicitly shown here, environmental factors like block effects can be easily included as covariates into the QTL model of each trait (2–4). In such models, environmental factors can have different effects on different curve characteristics. Alternatively, before QTL analysis, one can try to first adjust phenotypic data for (constant or time dependent) environmental factors. This means that residuals of the preliminary analysis are taken as phenotypes for consequtive QTL analysis. However, this kind of adjustment is likely to pre-correct the influence on the intercept (β0,i) only. In general, this kind of pre-correction practice may have many problems (see Martinez et al., 2005), which are likely to be more severe for time-dependent covariates.

Hierarchical model

All the models (1–4) presented above are considered simultaneously as parts of a larger hierarchical model. Let us denote the phenotype and marker data as Y and X, respectively. We denote the model parameters jointly as

θ={β1,…,βN,μ,B(0),B(1),B(2),I(0),I(1),I(2),ρ,σ2∈,τ2(0),τ2(1),τ2(2)}. Note that this vector includes all the unknown parameters needed in models (1–4). The posterior distribution P(θ∣X,Y) is proportional to the joint distribution P(X,Y,θ) of the data and parameters. This joint distribution can be described as a product of a likelihood P(Y∣θ) and the prior P(θ∣X), where the likelihood (with a pre-selected value of σe2) is

|

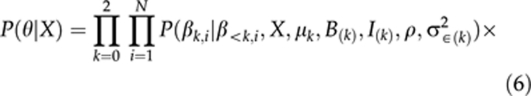

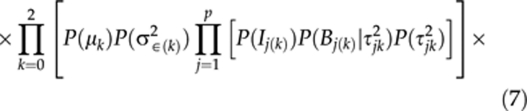

and the prior is

|

|

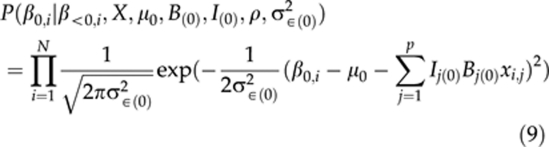

Here, the notation β<k,i refers to all the preceding terms in βi that appear before βk,i. For example, for β1,i, a preceding term is β0,i. The functional forms of priors P(βk,i∣β<k,i,X,μk,B(k),I(k),ρ,σ2∈(k)) are normal densities of the residuals of models (2–4) with mean zero and variance σ2∈(k) (see Sillanpää and Arjas, 1998). For the intercept, this is

|

Each individual prior in P(σ2∈(k)) is assumed to be an Inverse-Gamma (0.001, 0.001) and each of P(μk), P(ρ10),P(ρ20) and P(ρ21) to be N(0, 100). The Inverse-Gamma distribution supports values in positive range and the above normal distribution is rather flat. Therefore, they present practical priors applicable for many data sets without normalisation. The priors P(Ij(k)), P(Bj(k)∣τjk2) and P(τjk2) are covered in next section.

Model selection

Variable selection, selecting a specific set of trait loci contributing to each of the curve parameters, is here performed using the Bayesian adaptive shrinkage presented in Xu (2003). The adaptive shrinkage of Xu (2003) was found to perform well in comparison with other methods (O'Hara and Sillanpää, 2009). Following Xu (2003), a hierarchical prior

is assumed for coefficients so that Bj(0) ∼ N(0,τ2j0) and P(τ2j0) ∝ 1/τ2j0. It has been shown earlier that this formulation is mathematically equivalent to assuming Student's t-distribution for Bj(0) (Yi and Xu, 2008), which may induce a sparse model representation (Figueiredo, 2003; Xu, 2003; Hoti and Sillanpää, 2006). Similar assumptions are also made in

|

and in

|

The benefit of the adaptive shrinkage is that no tuning is needed, but one cannot make any prior assumptions from the degree of sparseness either.

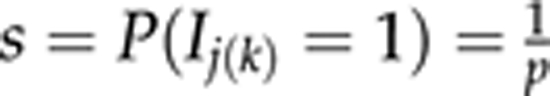

As in Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, (2009), there is another source of sparseness in our model, given by the indicator variables. In principle, the degree of sparseness can be controlled by specifying a small prior probability to include each marker into the model. Thus, as prior P(Ij(k)) for each marker j and each trait k (referring to one of the curve characteristics k=0,1, or 2), we can assume a Bernoulli distribution with fixed parameter  . However, we know from our earlier experience (Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009) that the shrinkage prior tends to dominate marker selection, so that this latter Bernoulli prior only has a modest influence on the degree of sparseness.

. However, we know from our earlier experience (Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009) that the shrinkage prior tends to dominate marker selection, so that this latter Bernoulli prior only has a modest influence on the degree of sparseness.

Missing genotype data

So far, we have implicitly assumed that QTLs are placed exactly at marker points. We assume that there may be a small amount of missing values among the genotypes xi,j of the data sample. In such case, the right hand side of the equation P(X,Y,θ)=P(Y∣θ)P(θ∣X), presented in the Hierarchical model above, should also include prior for P(X)=ΠiΠjP(xi,j). For this we have simply used Bernoulli prior P(xi,j) where all genotypic values are considered to be equally likely. In case of a population-based association studies, the use of known or estimated allele frequencies and assuming that genotypes occur in Hardy–Weinberg proportions may provide a more informative alternative to be used here. Although not considered here, it is possible to build up more efficient missing data models to account for dominant markers, linkage information and/or linkage disequilibrium information potentially available in the data sample. The use of linkage information necessitates the presence of haplotype information and/or multiple generations of pedigree data. The requirement for the use of linkage disequilibrium information is a dense set of markers and known physical or genetic marker distances. Missing marker (or QTL) genotype at arbitrary map positions can be predicted as pseudomarkers based on Mendelian segregation and marker distances (see Sillanpää and Arjas, 1999; Servin and Stephens, 2007 for details) and/or on linkage disequilibrium (Druet and Georges, 2010; Marchini and Howie, 2010).

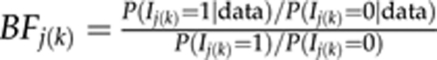

Markov chain Monte Carlo estimation and posterior summaries

We apply Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation to draw dependent samples from the joint posterior distribution of the unknowns (Robert and Casella, 2004). As an output from adaptive shrinkage, one obtains posterior estimated effect size at each considered position along the genome. Instead of monitoring the estimated effects or their posterior functions (Xu, 2003; Hoti and Sillanpää, 2006), one can take posterior expectations of indicator variables (see equations 2,3,4) to obtain estimates for posterior occupancy probabilities P(Ij(k)=1∣data). This is calculated simply as a proportion of MCMC rounds, in which the focal indicator is one. The posterior P(Ij(k)=1∣data) provides a natural model-averaged measure of evidence for a strength of phenotype–genotype association at locus j. Note that we obtain separate set of estimated posterior occupancy probabilities for each of the three curve parameters. For small QTL probabilities, it may be more meaningful to present them as Bayes factors (Kass and Raftery, 1995; Yi et al., 2007):  , which measures evidence for inclusion against exclusion of a locus. Although values of BF in range 1 to 3 are ‘not worth more than bare mention', values in interval (3, 10) represents ‘substantial' evidence (Jeffreys, 1961). Alternatively, a level of 2ln(BF)=2.1 has been suggested for declaring statistical significance (Kass and Raftery, 1995).

, which measures evidence for inclusion against exclusion of a locus. Although values of BF in range 1 to 3 are ‘not worth more than bare mention', values in interval (3, 10) represents ‘substantial' evidence (Jeffreys, 1961). Alternatively, a level of 2ln(BF)=2.1 has been suggested for declaring statistical significance (Kass and Raftery, 1995).

Heritabilities and genetic covariances/correlations

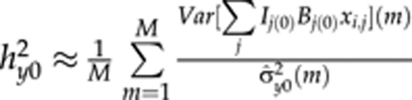

As polynomial curve parameters (intercept, slope and quadratic terms) are treated as latent traits in our model, we can estimate posterior heritabilities for each of them based on marker data. Like the curve parameters, these heritabilities are constant over time points. Using the QTL models (2–4), (narrow sense) heritabilities for curve parameters {β0,β1,β2}, can be estimated when there are no environmental effects in the QTL models. For the intercept,  , where σ̂y02(m) is the empirical phenotypic variance of β0 at MCMC round m, which can be estimated using sample variance of the curve parameter β0,i(m) values at MCMC round m. Here, M is total number of MCMC rounds, σ∈(0)2(m) is residual variance for an intercept in MCMC round m. Heritabilities for the slope

, where σ̂y02(m) is the empirical phenotypic variance of β0 at MCMC round m, which can be estimated using sample variance of the curve parameter β0,i(m) values at MCMC round m. Here, M is total number of MCMC rounds, σ∈(0)2(m) is residual variance for an intercept in MCMC round m. Heritabilities for the slope  and the quadratic term

and the quadratic term  are based on terms from QTL models (3) and (4), respectively. In the presence of environmental effects,

are based on terms from QTL models (3) and (4), respectively. In the presence of environmental effects,  where the numerator is the empirical variance of the predictor of the QTL model (2) in MCMC round m. In general, as was found by Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää (2009), indicator variables in QTL models (2–4) improve heritability estimation. Otherwise, the cumulative sum of markers with spurious effects tends to introduce some noise to the predictions.

where the numerator is the empirical variance of the predictor of the QTL model (2) in MCMC round m. In general, as was found by Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää (2009), indicator variables in QTL models (2–4) improve heritability estimation. Otherwise, the cumulative sum of markers with spurious effects tends to introduce some noise to the predictions.

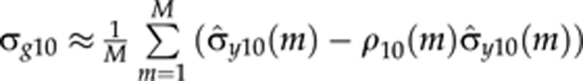

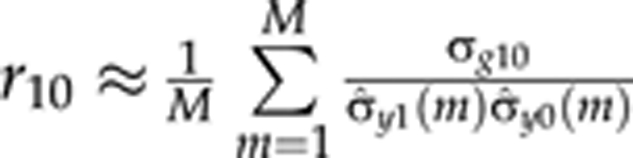

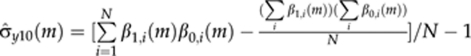

The use of multitrait QTL model makes it possible to also estimate genetic covariances (and correlations) between polynomial curve parameters. The genetic covariance between the intercept and the slope is estimated as  and the genetic correlation as

and the genetic correlation as  .

.

Here  is the empirical covariance between the intercept and the slope at MCMC round m. The term ρ10(m)σ̂y0(m) represents the residual covariance in MCMC round m. The genetic covariances (σg21 and σg20) and genetic correlations (r21 and r20) for other parameters are calculated using the same principle.

is the empirical covariance between the intercept and the slope at MCMC round m. The term ρ10(m)σ̂y0(m) represents the residual covariance in MCMC round m. The genetic covariances (σg21 and σg20) and genetic correlations (r21 and r20) for other parameters are calculated using the same principle.

Example analyses

Simulated data from QTLMAS 2009

We used public-simulated time-course data from QTLMAS 2009 workshop (Coster et al., 2010), which has been previously analysed in several other publications including Heuven and Janss (2010). The data set consists the growth curve measurements at five consecutive time points and 453 markers (within five chromosomes) measured from 2025 individuals. There were certain family structures present among the individuals in the data. There were altogether 18 QTLs influencing the growth curve phenotype among which three QTLs had five times larger effects on the trait than the rest of the QTLs. A map is available at http://www.qtlmas2009.wur.nl/UK/Dataset/ where one can find the marker ID and positions. The individual growth curves were simulated based on a logistic growth function, which is different from our polynomial growth function (equation 1). Thus, the logistic growth data can be seen as a test of the robustness of our method. We took a sub sample of 500 individuals, selected randomly within each family (but with equal contribution from all full-sib families). Only 50 families with phenotype data were used, which resulted in 10 individuals per family.

Real data on scots pine (Pinus sylvestris)

We genotyped a set of 160 AFLPs on 250 individuals from a full-sib family of Scots pine that was established in 1988. The parents of the full-sib cross are part of the Swedish breeding population; both parents come from northern Sweden (AC3065 latitude 6508′ and Y3088 latitude 6409′).

Total DNA was extracted from vegetative buds. The buds where pealed, dried and grinded. The DNA extraction was made using the CTAB method. The AFLP markers were produced according to Vos et al. (1995). The following 15 primer enzyme combinations were used E-act/M-cctg, E-act/M-cccg, E-act/M-ccgc, E-act/M-ccgg, E-act/M-ccag, E-acg/M-cctg, E-acg/M-cccg, E-acg/M-ccgc, E-acg/M-ccgg, E-acg/M-ccag, E-aca/M-cctg, E-aca/M-cccg, E-aca/M-ccgc, E-aca/M-ccgg and E-aca/M-ccag.

The amplified fragments were sent to the DNA facility at Iowa State University, USA and run on ABI3100 Genetic Analyzer. The mapping data were analysed with GeneMarker v1.6 (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA).

The height measurements were carried out with a measuring stick of telescope type from the ground to the terminal bud. The height was repeatedly measured 11 times between the years 1996 and 2007. The phenotype measurements from 1996 to 1999 have already been used for QTL analysis and published in Lerceteau et al. (2001). After more close inspection of temporal measurements, we decided to exclude 14 individuals from the collected data because those individuals showed negative enrichment of height in some of the consecutive time points because of some damage in the apical shoot due to wind or snow. Thus, our final data set contained 236 individuals.

Simulated pine data replicates

Latent trait phenotypes

We took above real Scots pine data (236 individuals, 160 AFLP markers; xi,j, i=1,…,236 j=1,…,160) as starting point for our simulation. First with equal probabilities we completed (by sampling once) all the missing genotypes so that there was no missing genotypes in simulated data. For each individual, we simulated 10 replicates of a vector βi containing a new set of latent trait phenotypes from the modified versions of the QTL models (2–4) by setting ρ10=ρ20=ρ21=0 and assuming that the residual vector ∈i=(∈i(0), ∈i(1), ∈i(2)) is drawn from a tridimensional normal distribution,  , with a mean vector

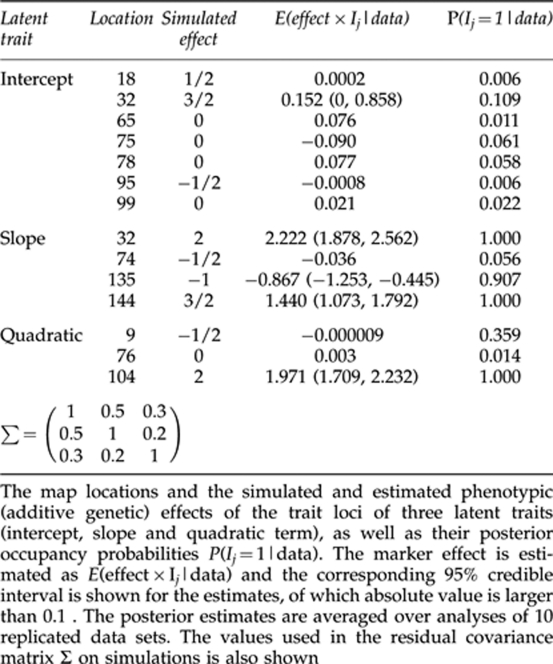

, with a mean vector  and a covariance matrix Σ specifying between-trait residual dependencies. For all the replicates, three QTLs (at loci 18, 32 and 95) with average joint heritability of 0.39 (replicates varied in range (0.36–0.47)) were simulated for the 1st latent trait–intercept, four QTLs (at loci 32, 74, 135 and 144) with average heritability of 0.66 (replicates in (0.62–0.71)) for the 2nd latent trait-slope and two QTLs (at loci 9, 104) with average heritability of 0.50 (replicates in (0.43–0.56)) for the 3rd latent trait—quadratic term. Here, indicators Ij(k),j=1,…,160, k=0, 1, 2 were set to one for QTLs and to zero for non-QTLs. The contents of Σ and the other QTL-model parameters used in our simulations are described in Tables 1 and 2.

and a covariance matrix Σ specifying between-trait residual dependencies. For all the replicates, three QTLs (at loci 18, 32 and 95) with average joint heritability of 0.39 (replicates varied in range (0.36–0.47)) were simulated for the 1st latent trait–intercept, four QTLs (at loci 32, 74, 135 and 144) with average heritability of 0.66 (replicates in (0.62–0.71)) for the 2nd latent trait-slope and two QTLs (at loci 9, 104) with average heritability of 0.50 (replicates in (0.43–0.56)) for the 3rd latent trait—quadratic term. Here, indicators Ij(k),j=1,…,160, k=0, 1, 2 were set to one for QTLs and to zero for non-QTLs. The contents of Σ and the other QTL-model parameters used in our simulations are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Analysis of 10 simulated data replicates.

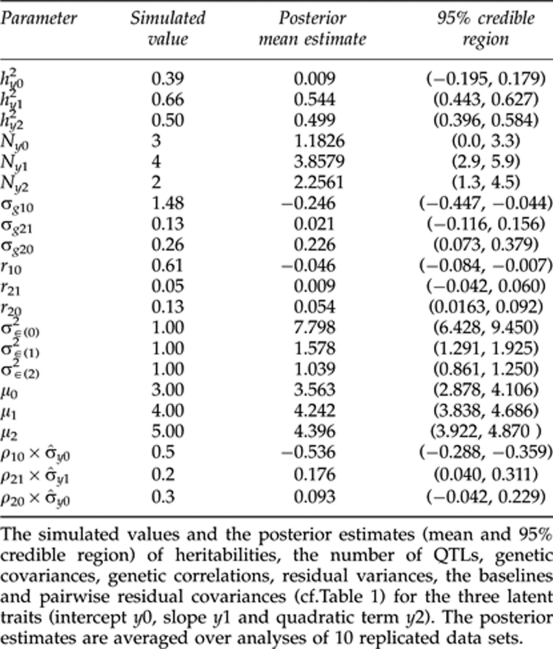

Table 2. Analysis of 10 simulated data replicates.

Functional trait phenotypes

Given the replicated values of curve parameters (that is, latent traits) above, we simulated 10 replicates of phenotypic measurements at 11 consecutive time points for each individual. For this, we used the modified version of the model (1) with time-specific residual variances {σ12,…,σ211}={2,3,5,4,3,5,3,2,3,5,4}. These time-specific residual variances describe how much individual phenotypic measurements (at each time point) are allowed to deviate from individual-specific functional curve. Eventually this process produced 10 data replicates.

Creation of data sets with missing phenotypes

As a goodness-of-fit test for the model, we wanted to study also the robustness of our method for increased number of missing phenotype measurements in time points. Thus, for every other time point, we introduced missing entries by deleting ∼50% of the phenotypes randomly. Note that individuals with missing phenotypes at consecutive time points are not neccessarily the same. The same treatment was carried out for a real Pine data set and one additional simulation replicate. After this treatment, we had 13 different Pine data sets: an original real data set, 10 simulation replicates, and one real and one simulated data set with increased missingness.

Analyses

In the following, we introduce results from five different analyses. First, we present QTL analysis of simulated QTLMAS 2009 data set. Then, we cover QTL analysis of 10 simulation replicates and prediction of unobserved phenotypes for additional simulated Pine data set. Finally, we show results from QTL analysis and phenotype predictions with real Pine data. In real data analyses, we included environmental block effect (of four blocks) to each of the QTL models (2–4) and assumed that block effects in each model are independently normally distributed with common block variance. For three block variances, we assumed Inverse-Gamma (0.01, 0.01) priors.

For implementation and parameter estimation, we used WinBUGS 1.4.3 software (Spiegelhalter et al., 2005). We assumed prior  for each locus j and for each latent trait k in QTLMAS 2009 data analysis and for each j and k in simulated and real Pine data analyses. As WinBUGS does not allow the use of improper priors such as P(τjk2)∝1/τjk2, we used its finite approximation (for details, see Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009). For each data replicate, we ran one chain for 30 000 MCMC iterations, discarding 5000 initial samples as burn-in and thinning the remainder to each 10th sample (that is, storing every 10th sample). This resulted in 2500 samples to be used in estimating the posterior for each data replicate. For prediction of unobserved phenotypes in simulated and real data, as well as the real Pine data QTL-analysis, we ran one chain for 50 000 MCMC iterations and used a burn-in period of 5000 samples and a thinning of 5. This resulted in 9000 MCMC samples. The MCMC sample paths of several different parameters were visually inspected based on some prior runs. The running time was practically the same in phenotype prediction analyses and in real Pine QTL analysis, being about 114 h for the whole analysis on an Intel Core 2 with 1.86 GHz and 1.94 GB of RAM. On the same computer, running through 10 simulation replicates took about 30 days. For the QTLMAS 2009 data analysis, we ran 10 000 MCMC iterations by omitting 6000 initial samples as burn-in and had no thinning.

for each locus j and for each latent trait k in QTLMAS 2009 data analysis and for each j and k in simulated and real Pine data analyses. As WinBUGS does not allow the use of improper priors such as P(τjk2)∝1/τjk2, we used its finite approximation (for details, see Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009). For each data replicate, we ran one chain for 30 000 MCMC iterations, discarding 5000 initial samples as burn-in and thinning the remainder to each 10th sample (that is, storing every 10th sample). This resulted in 2500 samples to be used in estimating the posterior for each data replicate. For prediction of unobserved phenotypes in simulated and real data, as well as the real Pine data QTL-analysis, we ran one chain for 50 000 MCMC iterations and used a burn-in period of 5000 samples and a thinning of 5. This resulted in 9000 MCMC samples. The MCMC sample paths of several different parameters were visually inspected based on some prior runs. The running time was practically the same in phenotype prediction analyses and in real Pine QTL analysis, being about 114 h for the whole analysis on an Intel Core 2 with 1.86 GHz and 1.94 GB of RAM. On the same computer, running through 10 simulation replicates took about 30 days. For the QTLMAS 2009 data analysis, we ran 10 000 MCMC iterations by omitting 6000 initial samples as burn-in and had no thinning.

In the missing data analyses, the prediction accuracy (between true and predicted phenotypes) was assessed at each time point (with increased missingness) by monitoring posterior distributions of relative and absolute prediction error and linear correlation between true and predicted phenotypes. Calculations of these quantities were based on posterior predictive distributions for individuals with missing phenotypes. As stated in Lee et al. (2008), this kind of analysis gives information also about the accuracy of this method in estimating genomic breeding values (Meuwissen et al., 2001; Piyasatian et al., 2007; Lorenzana and Bernando, 2009; Heffner et al., 2009).

Results

Simulated QTLMAS 2009 data set

QTL identification

The loci showing elevated posterior occupancy probabilities in the three latent traits are shown in Table 3. The occupancy probabilities of all the other loci were lower than 0.01. The posterior estimated heritabilities for the three latent traits are shown in Table 4. As expected, because different growth functions were used during simulation and analysis, the QTLs simulated for one trait seem to be ‘scattered' among all three traits in the analysis. The same phenomenon is visible also in the estimated heritabilities.

Table 3. QTLMAS 2009 data analysis.

| Latent trait | Locus | Closest simulated QTL | E(effect × Ij∣data) | P(Ij=1∣data) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 36 (0.4153) | (0.4245) 36–37 | 1.528 | 1.0 |

| 98 (1.0359) | (1.0455) 98–99 | 0.005 | 0.015 | |

| 137 (1.4829) | (1.4889) 138–139 | 0.177 | 0.59 | |

| 173 (1.8574) | (1.8864) 174–175 | −0.017 | 0.034 | |

| 218 (2.2707) | (2.2622) 216–217 | −0.004 | 0.012 | |

| 232 (2.4005) | (2.5609) 243–244 | 0.2022 | 0.17 | |

| 288 (3.048) | (3.0962) 293–294 | −0.295 | 0.68 | |

| 408 (4.5353) | (4.5971) 411–412 | 0.019 | 0.055 | |

| 421 (4.6635) | (4.7719) 432–433 | 0.013 | 0.022 | |

| Slope | 36 (0.4153) | (0.4245) 36–37 | 0.438 | 1.0 |

| 38 (0.4472) | *(0.5425) 51–52 | 0.005 | 0.058 | |

| 81 (0.9137) | (0.8765) 77–78 | 0.295 | 1.0 | |

| 240 (2.5252) | (2.5609) 243–244 | 0.001 | 0.017 | |

| 360 (3.8701) | (3.8639) 358–359 | 0.141 | 1.0 | |

| Quadratic | 35 (0.4029) | (0.4245) 36–37 | −0.130 | 1.0 |

| 37 (0.4447) | *(0.5425) 51–52 | 0.145 | 0.72 | |

| 118 (1.3058) | (1.3302) 118–119 | −0.001 | 0.014 | |

| 134 (1.4743) | (1.4889) 138–139 | 0.001 | 0.017 | |

| 140 (1.5242) | (1.4889) 138–139 | 0.001 | 0.012 | |

| 222 (2.3108) | (2.2622) 216–217 | −0.001 | 0.018 | |

| 223 (2.318) | (2.2622) 216–217 | 0.001 | 0.010 | |

| 314 (3.3746) | (3.3652) 313–314 | −0.001 | 0.014 |

The three latent traits are listed in the first column. The second column ‘Locus' refers to the marker loci (with their map locations in parenthesis), which showed non-negligible signals in QTL analysis. The next column refers to the map position of true QTLs (in parenthesis), followed by their two flanking markers. The symbol * indicates the position of the second closest major QTL. The posterior means of the marker effects (viz. Bj(k) × Ij(k) for latent trait k) and the posterior occupancy probabilities P(Ij=1∣data) for detected loci j are given in the last two columns.

Table 4. QTLMAS 2009 data analysis.

| Parameter | Simulated value | Posterior mean estimate | 95% credible region |

|---|---|---|---|

| hy02 | 0.50 | 0.24 | (0.13, 0.34) |

| hy12 | 0.50 | 0.99 | (0.984, 0.995) |

| hy22 | 0.50 | 0.75 | (0.71, 0.79) |

The posterior estimates (mean and 95% credible region) of heritabilities of three latent traits (intercept y0, slope y1 and quadratic term y2). Note that simulated values correspond to the heritabilities simulated under different growth function.

The three major QTLs in the data set (at 36, 51 and 78) were in chromosome 1 with map locations 0.4245, 0.5425 and 0.8765 (see Figure 3 in Coster et al., 2010). Locus 36 or 35, adjacent to the first major QTL (at 36), showed QTL-occupancy probability of 1.0 in all three latent traits. The QTL probabilities of 0.058 and 0.72 were found for loci 38 and 37 in slope and quadratic term, respectively. These positions are evidently more close to the first major QTL (at 36) but the second major QTL (at 51) is not more than 10 c away from them. The locus 81, which is close to the third expected QTL at position 78, acquired QTL probability of 1.0 for the slope.

Markers near the four minor QTLs (98, 118, 138 and 174) in chromosome 2 also obtained some support in the analysis. The markers 98, 137 and 173 obtained elevated signals in the intercept and markers 118, 134 and 140 in the quadratic term. All of them are extremely close to the one of four simulated minor QTLs in chromosome 2. Generally, the level of support was not strong, expect for locus 137 where the posterior QTL probability was 0.59.

The markers near two minor QTLs (217 and 243) out of four simulated minor QTLs in chromosome 3 got support in the analysis, but the level of support was generally quite small. Such putative QTL positions were the markers 218 and 232 (with QTL probabilities 0.012 and 0.17, respectively) for intercept, the marker 240 (with QTL probability 0.017) for slope, and the markers 222 and 223 (with QTL probabilities 0.018 and 0.01, respectively) for quadratic term.

The markers near three minor QTLs (293, 314 and 358) out of four simulated minor QTLs in chromosome 4 got support in the analysis. The QTL probabilities for loci 288, 314 and 360 were 0.68, 0.014 and 1.0, respectively. The simulated minor QTL, which was not found in the analysis had small effect size.

The markers near two minor QTLs (411 and 432) out of three simulated minor QTLs in chromosome 5 got support in the analysis. The loci 408 and 421 had QTL probabilities 0.055 and 0.022 in intercept, respectively. The simulated minor QTL, which was not found in the analysis, had a slightly larger effect size than the two others.

To better understand the ‘scattering' of QTLs among latent traits, we also calculated the pairwise correlation between the orginal simulation parameters of the logistic growth function and the posterior estimated values of the three latent traits (see Table 5). As can be seen in the table, generally these correlations are moderate except the correlation of 0.61 between logistic curve parameter 1 and the quadratic term.

Table 5. QTLMAS 2009 data analysis.

| Parameter | β0 | β2 | β3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| par1 | 0.46 | −0.37 | 0.61 |

| par2 | 0.42 | −0.35 | 0.29 |

| par3 | −0.29 | 0.41 | −0.13 |

The pairwise correlation calculated between the three parameters of the logistic growth function (par1, par2, par3) and the three posterior mean-estimated parameters of the polynomial function (β0,β1,β2).

Heuven and Janss (2010) analysed a sub sample of 1000 individuals from the same QTLMAS 2009 data set by using the growth function assumed in the data simulation process. Because of this, their heritability and QTL position estimates showed consistency among the latent trait parameters. To compare the genomic positions of the found QTLs roughly (without caring about which trait each QTL contributes to or how strong QTL signals were obtained), it is fair to say that comparable set of QTL positions were identified in our analyses with the data sample, which was only half of their sample size.

Simulated Pine data sets

QTL identification

To assess empirical power of our method in simulated Pine data, the estimated posterior occupancy probabilities (averaged over 10 data replicates) for true and false QTLs in the three latent traits are shown in Table 1. Generally, the major QTLs with effect size of at least one (in absolute value) were correctly found in all cases, whereas the QTLs with effect size 1/2 were correctly identified only once and was unidentified three times. For the intercept, the highest QTL-occupancy probability 0.1 was found at correct major QTL with large effect (at locus 32), but the signal was very low. The weak QTL probabilities were found at loci 65, 75, 78 and 99, which were all false positives. All the other QTL probabilities were smaller than 0.01 and no signals (QTL probabilities 0.006 and 0.006) were found at minor QTLs (18 and 95). For the slope, the high posterior occupancy probability (between 0.9 and 1.0) was obtained for three true QTLs with large effects (at loci 32, 135 and 144) and 0.06 for the fourth minor QTL. Practically, there were no false positives in slope because all the other positions had QTL probabilities, which were smaller than 0.01. Note that correctly identified QTL at locus 32 was pleiotropic and had large effects on both intercept and slope. For the quadratic term, all simulated QTLs were correctly identified so that the posterior occupancy probability 1.0 was obtained for the major QTL at locus 104 and probability of 0.36 for minor QTL at locus nine. The weak signal (QTL probability 0.014) was found at locus 76, which was false positive and all the other loci had QTL probability that was smaller than 0.01. It is worth emphasizing here that putting the QTL probability threshold to 0.1 would result in the elimination of all the false positives in these data.

Estimation of the model parameters

As the indicator and effect size always appear together as a pair in the models (2–4), the two quantities are obviously confounded in their estimates. Thus, the QTL-effect estimates are presented only in the form of the product in Table 1. Generally, these posterior means of the estimated QTL-effects (averaged over replicates) are clearly closer to their true simulated values when the QTL-occupancy probability is high, and are constantly small when the corresponding QTL probability is low. The exception to this is the minor QTL in quadratic term where QTL probability was 0.36 but the effect size was practically zero. The simulated and estimated values for several other model parameters are presented in Table 2. The posterior mean estimate of the heritability for the intercept was 0.01, which was much lower than the true simulated mean value of 0.39. Here the 95 % credible interval does not contain the true value. These estimates are biased probably because the support for the major QTL was weak and two minor QTLs were unidentified in the QTL analysis. For the slope, we obtained an underestimated posterior mean heritability of 0.54 while the true value was 0.66. Here the 95% credible interval averaged over replicates does not contain the true simulated value because one minor QTL was unidentified in the QTL analysis. For the quadratic term, heritability was accurately estimated with posterior mean 0.50, which coincides with the true value. Moreover, the 95% credible interval was rather narrow, indicating that both simulated QTLs for the quadratic term were correctly identified. On the other hand, the number of QTLs is accurately estimated for the slope and the quadratic term while that for the intercept is badly underestimated.

Although the posterior means of the parameter estimates connected to the slope and quadratic term are generally very close to their true simulated values, the estimates connected to the intercept are much more biased (for example, residual variance). An exception to this general trend comes from the baseline parameters, which coincide closely with their true values in all cases. Similarly, the posterior mean of genetic covariance 0.23 and of genetic correlation 0.05 between an intercept and a quadratic term are not very far from their true values (0.26 and 0.13, respectively), while the corresponding parameters between a slope and a quadratic term are more biased. To compare the estimate of ρ10 to the simulated residual covariance, we first have to multiply it with the standard deviation of latent trait σ̂y0, which gives σ̂10=ρ10 × σ̂y0≈−0.5, which is not close to 0.5. Similar reasoning yields estimates of σ̂21≈0.18 and σ̂20≈0.1, which are closer to values of 0.2 and 0.3.

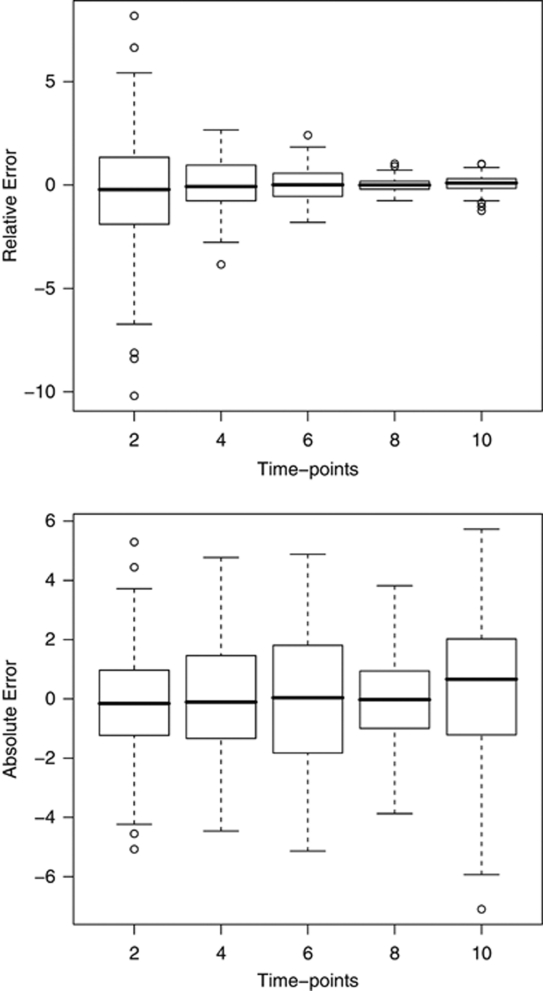

Prediction of unobserved phenotypes

For simulated data, the values of correlation coefficients between the true and predicted phenotypes (their posterior means) were calculated at five different time points with increased amount of missing phenotypes. These correlations were almost one in all cases (0.992, 0.998, 1.0, 1.0 and 1.0 for five time points), which indicates that our method was able to correctly predict the original ordering of the unobserved phenotypes. For simulated data, the boxplots in Figure 1 present the relative errors (top) and absolute errors (bottom) of the predicted phenotypes at five time points with increased amount of missing phenotypes. These quantities are calculated from posterior predictive distributions of unobserved phenotypes. The reason why relative errors are decreasing as function of time is the fact that our simulated growth phenotype is systematically increasing with time. This means that error values on the right are systematically divided by larger (true) values. In this case, absolute error is providing better indication of phenotype prediction accuracy. At each measurement point, the mean of the absolute error stays in the vicinity of zero and one cannot see the systematic trend of making larger absolute errors, while the actual predicted values increase from left to right.

Figure 1.

The prediction accuracy of the phenotypes in the simulated data. Boxplots of relative errors (top) and absolute errors (bottom) for predicted phenotypes at five time points, which had increased missingness. Errors are shown on the y-axis and the time-points on the x-axis. The absolute error is calculated as difference between predicted (posterior mean) and true phenotype and relative error is obtained as 100 times absolute error divided by the absolute value of the true phenotype.

Real data on Scots pine

QTL identification

From the real data analysis, the estimated posterior occupancy probabilities and effect sizes of QTLs in the three latent traits are shown in Table 6. Even though these QTL probabilities are generally low, our suggested loci show clearly elevated signals compared with the general level of that in other positions. However, based on our replicated simulation analysis, our power here may be rather weak. As it is hard to judge small QTL probabilities, we decided to present also the Bayes factor (BF) as BF scales the corresponding marker evidence with respect to the prior probability. For the intercept, the highest QTL probability 0.009 (BF 1.50) was found for locus 156 (act/ccgg_433), while the other QTL probabilities were all smaller than 0.0085 (BF <1.335). However, at QTL threshold level 0.01, which is rather low, one can conclude that no QTLs were found for intercept. For the slope, the highest QTL probability 0.012 (BF 1.90) occurs at locus 21 (aca/ccgc_194) and all the other QTL probabilities were smaller than 0.009 (BF <1.391). For the quadratic term, there were two putative QTLs (at loci 38 and 97; aca/ccgg_277 and acg/ccgc_71) with QTL probabilities 0.012 and 0.013 (BFs 1.88 and 2.17, respectively). The other QTL probabilities were smaller than 0.008 (BF <1.157). Based on the general BF categories suggested by Jeffreys (1961), these evidence are from class of ‘not worth more than a bare mention'. However, one should keep in mind that there are two sources of shrinkage in our QTL models, where the indicators had milder influence on the overall shrinkage than the effect coefficients (Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009). Thus, in the presence of small sample size, it might be fair to conclude that the BFs presented here are kind of ‘lower bounds of their true values' and should be interpreted in the light of much smaller prior inclusion probability. However, even if influence of this ‘double shrinkage' would be modest, it is likely that these findings are still rather weak.

Table 6. Scots pine data analysis.

| Latent trait | Location | E(effect × Ij∣data) | P(Ij=1∣data) | Bayes Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 156 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 1.50 |

| Slope | 21 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 1.90 |

| Quadratic | 38 | −0.0006 | 0.012 | 1.88 |

| 97 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 2.17 |

The locations and the estimated phenotypic (additive genetic) effects of the trait loci of three latent traits (intercept, slope and quadratic term), as well as their posterior occupancy probabilities P(Ij=1∣data) and the corresponding Bayes factors. The effect size is estimated as E(effect× Ij∣data).

Estimation of the heritabilities and other parameters

The posterior estimates for different model parameters including latent trait heritabilities are shown in Table 7. The heritabilities are small for all latent traits, which supports the fact that genetic variation is generally low.

Table 7. Scots pine data analysis.

| Parameter | Posterior mean estimate | 95% credible region |

|---|---|---|

| hy02 | 0.0004 | (0, 0.003) |

| hy12 | 0.0006 | (0, 0.006) |

| hy22 | 0.0003 | (0, 0.004) |

| σ∈(0)2 | 1148.0 | (953.5, 1373.0) |

| σ∈(1)2 | 95.54 | (79.83, 114.5) |

| σ∈(2)2 | 0.080 | (0.067, 0.096) |

| μ0 | 93.07 | (−23.22, 172.3) |

| μ1 | 52.07 | (42.37, 61.19) |

| μ2 | 2.723 | (2.364, 3.082 ) |

| block (0,1) | 72.93 | (–5.187, 189.8) |

| block (0,2) | 73.48 | (–4.655, 190.0) |

| block (0,3) | 81.36 | (–0.659, 200.1) |

| block (0,4) | 76.15 | (–3.133, 195.3) |

| block (1,1) | −0.814 | (–7.545, 7.120) |

| block (1,2) | −3.933 | (–11.07, 3.989) |

| block (1,3) | 0.355 | (–6.416, 8.406) |

| block (1,4) | 6.842 | (0.301, 15.94) |

| block (2,1) | −0.165 | (–0.402, 0.077) |

| block (2,2) | −0.043 | (–0.277, 0.202) |

| block (2,3) | 0.110 | (–0.120, 0.359) |

| block (2,4) | 0.095 | (–0.138, 0.362) |

| σ2block[0] | 21990.0 | (0.022, 131600.0) |

| σ2block[1] | 57.39 | (4.600, 291.6) |

| σ2block[2] | 0.066 | (0.007, 0.317) |

The posterior estimates (mean and 95% credible region) of heritabilities, residual variances, the baselines for the three latent traits (intercept y0, slope y1 and quadratic term y2). Additionally, the posterior estimates for the block coefficients and their corresponding block variances are shown for the three latent traits.

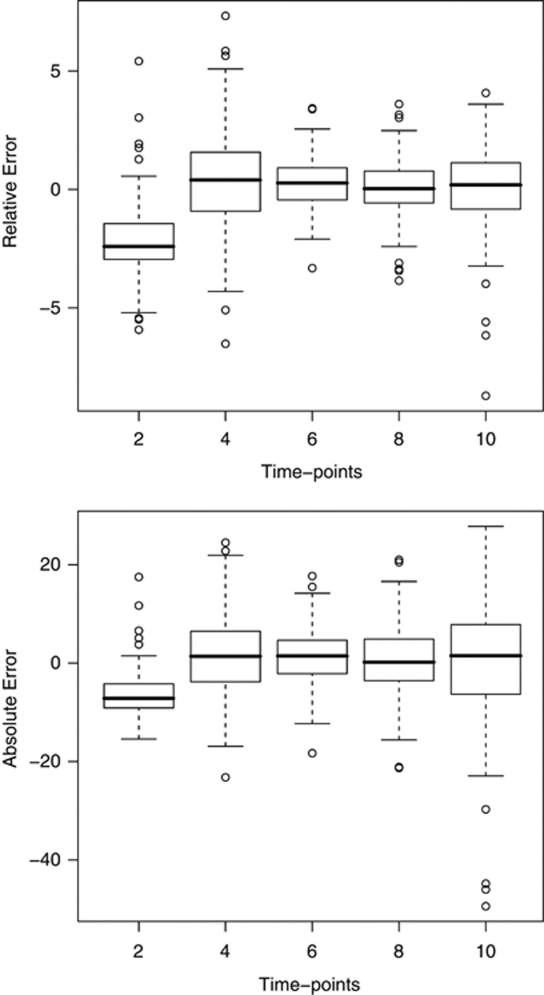

Prediction of unobserved phenotypes

For real data, the value of linear correlations coefficient between the true and predicted phenotypes (their posterior means) were calculated at five different time points with increased amount of missing phenotypes. As in simulated data, the correlation coefficients here were also extremely high in all cases (0.993, 0.984, 0.995, 0.995 and 0.980 for five time points), which indicates that our method was able to correctly predict the original ordering of the unobserved phenotypes. It is likely that environmental block effects are at least partly responsible for these predictions, because the estimated QTL probabilities and heritabilities in these data set were so small. For real data, the boxplots in Figure 2 present the relative errors (top) and absolute errors (bottom) of predicted phenotypes at five time points with increased amount of missing phenotypes. It is clear that the first time point seems to suffer from some bias, which may reflect a disagreement between the polynomial function and the data or difficulties in mapping QTLs for the intercept.

Figure 2.

The prediction accuracy of the phenotypes in the Scots pine data. Boxplots of relative errors (top) and absolute errors (bottom) for predicted phenotypes at five time points, which had increased missingness. Errors are shown on the y-axis and the time-points on the x-axis. The absolute error is calculated as difference between predicted (posterior mean) and true phenotype and relative error is obtained as 100 times absolute error divided by the absolute value of the true phenotype.

Discussion

A conceptual description of the new method for mapping functional QTLs was presented in this paper. Because of its conceptual nature, it is worth emphasising that practical and scalable implementations of the method are out of the scope of this very first paper. The method is based on mapping QTLs which influence the curve parameters (that is, latent traits) describing functional curve of time-dependent phenotypic measurements (cf. Gee et al., 2003; Heuven and Janss, 2010). Unlike the others, we use a multitrait multiple-QTL model, which is essentially a single Bayesian-hierarchical model allowing for information flow and incorporation of uncertainties between different levels of the hierarchy. Also, the multitrait analysis is known to improve the accuracy and power of QTL detection (Jiang and Zeng, 1995). Note that Gee et al. (2003) and Heuven and Janss (2010) used two-stage approaches and performed QTL analysis for each parameter of the curve separately. One possible application field of the hierarchical model presented here is to map regulatory loci controlling time-dependent changes of gene expressions (eQTL, transcript abundances) or protein expressions over time (pQTL) (Reis et al., 2001; Foss et al., 2007; Ge et al., 2010). In such applications, eQTLs can influence the curve parameters, which again determine the individual's expression curve over time. However, in these situations, the current polynomial curve function may not be flexible enough to describe the required nonlinear shape of the expression profile (see Luan and Li, 2004; Qu and Xu, 2006). Of course, this unsuitability can be somewhat handled by giving high value to σe2 but at the same time, it has a negative influence on statistical power to find QTLs. Thus, one may need to replace the model (1) with a more flexible function, for example, one which is possibly first estimated based on available set of featured genes from the biological process in question (Luan and Li, 2004).

There is recent interest in using recursive relationships or feedback effects in multitrait quantitative genetic models (Gianola and Sorensen, 2004; Wu et al., 2010). Thus, we shortly comment on differences between such recursive models and our autoregressive formulation of multitrait QTL model. First, our model assumes residual independence while these recursive models assume residual dependence. Second, we have effects of trait 1 to trait 2 and trait 3 but not the other way round while recursive models may include all the effects or cyclic dependencies between the traits. Although it is possible to include more complicated between-trait interdependencies into the model, it is not well justified in our setting. One should remember that our decision to include autoregressive coefficients to the QTL models (2–4) was made to improve computational efficiency only.

The multitrait multiple-QTL part constitutes one level of our larger hierarchical multilevel model. It represents a new and efficient way to handle residual dependencies between quantitative traits. How this part of the model performs in the presence of a larger number of traits (for example, higher order polynomials) deserves to be more carefully studied in the future. Moreover, it is still an open question here what kind of modifications are needed for models (2–4) when the trait values are observed quantities rather than model parameters.

As seen in examples, the presented hierarchical model can be used to predict unobserved phenotypic measurements at arbitrary time points from posterior predictive distributions. The curve parameters (and underlying QTL model parameters) estimated based on observed measurements from all individuals provide information for predicting a single time-point of an individual. As collecting phenotype data is expensive, one application of the model may be to use this feature in data collection. Thus, one can systematically reduce the number of individuals collected at some of the time points by randomly selecting measured individuals at each point. To maintain accuracy in the curve parameters, as illustrated in our examples, one can collect systematically more complete data sample at every other measurement point. However, it is important to keep in mind here that the hierarchical model does not represent informative missing data model similarly as in Sillanpää and Noykova (2008), because missing values occur here at the highest level of the hierarchy in the model. This means that only the observed part of phenotypes over time points have influence on the posterior distributions of the model parameters. Therefore, the degree of missingness at any time point should not fluctuate too much from other time points.

In our analysis of simulated data replicates, we found that our method had problems to find QTLs for the intercept while analysis for the other two latent traits worked much better. Weak signals were also found in real data analysis while our method worked clearly better for the simulated QTLMAS data set, where the sample size was relatively large. However, our suggested position of the second major QTL in chromosome 1 could have been more accurate with larger sample. These results may indicate the importance of having large sample size in functional QTL studies. On the other hand, our method was able to provide accurate phenotype predictions with small data.

The method was implemented using WinBUGS software, which allows MCMC estimation of the hierarchical model parameters without requiring derivation of the details of the sampling algorithm such as fully conditional posterior distributions. When the size of the marker sets increases and/or the WinBUGS implementation becomes too slow for the practical purposes, one can proceed by (i) implemenenting one's own MCMC sampler using a convenient programming language or (ii) perform pre-selection of the marker set to reduce the model dimensionality. For the variable selection part of our hierarchical model, we recommend relying on some existing sampling algorithms and their full conditionals, which may guarantee the sufficient mixing properties of the sampler. For example, see Banerjee et al., 2008 for implementational details of suitable MCMC sampling algorithm in this respect. The sampling steps for individual-specific functional curve parameters can then be included as additional steps into the sampling scheme of Banerjee et al., 2008. The full conditional distributions of functional curve parameters have analytical forms because of conjugacy: both the likelihood and the prior are densities of the normal distribution (details not shown). The pre-selection of the markers can be carried out for example, by first estimating the curve parameters and then eliminating the markers that are weakly correlated with each curve parameter with a single-marker test (see Cho et al., 2010). Alternatively, one can use pre-selected set of haplotype-tagging markers in the analysis (see Lin and Altman, 2004).

In Pinaceae, age-to-age correlations and narrow-sense heritability for height have generally been reported to be low to moderate with an increasing tendency with age (Lambeth, 1980; Costa and Durel, 1996; Jansson et al., 2003, 2005, but see Gwaze, 2009). Low correlation across ages has also been observed for QTL identification (Plomion et al., 1996; Verhaegen et al., 1997; Kaya et al., 1999); this is partly due to different set of genes expressed at each life stage, although environmental variance is expected to be large, especially at early growth stages. Although, a time-point QTL analysis of Lerceteau et al. (2001) reported consistency in the number and location of QTLs for height across four years in Scots pine, trees were still at the juvenile stage and QTL expression at mature stages was not verified. A study of Lerceteau et al. (2001) was based on 94 individuals and a total of 152 dominant markers (59 maternal and 93 paternal), but their marker set was different from our marker set here which makes the comparison difficult. However, we also detected three QTLs in our study when analysing functional growth data for 11 years in the same Scots pine population. Although a similar number of QTLs was found in both studies, QTLs may not be equivalent as we used a functional QTL-mapping approach. A functional QTL mapping is an alternative approach that focuses on the developmental features of the dynamic trait (for example, growth curve) overcoming the problem of age-specific QTL expression. Many studies in conifers have been devoted to analyse growth trajectories (see Balocchi et al., 1993; Magnussen and Kremer, 1993; Danjon, 1994; Gwaze et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009). However, to our knowledge, no QTL analysis in conifers has been trying to investigate functional traits, the only published works being in Populus (Wu et al., 2003; Ma et al., 2004). Our analysis revealed three QTLs for growth parameters such as slope (speed of growth) or quadratic term (curvature or timing of growth cessation), which are essential for the genetic improvement of forest trees and can only be assessed by means of dynamic trait analysis. Growth curve parameter estimation has critical advantages such as the fit of the data to a biologically meaningful mathematical model, which furthermore helps to correct for data irregularities due to human errors or environmental effects. Furthermore, dynamic trait analysis could also be useful to predict growth at ages where measurements are missing. Growth trajectory parameters can be shifted as a response to selection. Breeding on growth curves are used in animal breeding (Tholon and de Queiroz, 2009; Haraldsen et al., 2009) and the same results could be expected when used in forest tree breeding.

In our hierarchical model, additive genetic variation (of QTLs) influences the curve parameters, which in turn control the shape of the polynomials over time. In this context, we illustrated estimation of additive genetic variances and heritabilites for these curve parameters and genetic covariances between them. Unlike the common practice (Gwaze et al., 2002; Kulathinal et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009), our analysis does not provide time-specific heritability or covariance estimates at all. However, it may be more meaningful from a breeding point of view to actually inspect the genetics and estimate the genomic breeding values underlying the curve characteristics (which control the dynamic behaviour of the trait), rather than inspecting genetics at different time-points. For example, the slope will be easy to interpret from a biological point of view as ‘speed of growth'. Note that the additive genetic variance was estimated as the variance of the genomic breeding values which provided a marker-based estimate for heritability (cf. Meuwissen et al., 2001; Xu, 2003; Pikkuhookana and Sillanpää, 2009; Sillanpää, 2011). Generally, these heritability estimates (when the same growth function was used in simulation and analysis) were underestimated due to presumably small sample size, but the accuracy of the predicted phenotypes were, especially high, and they both will motivate future studies.

The model specification codes (written in WinBUGS) used in this article and instructions to use them are freely available for research purposes at URL http://www.rni.helsinki.fi/~mjs/.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Crispin M Mutshinda for useful discussions and valuable comments on the manuscript and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a research grant from the Academy of Finland, University of Helsinki's Research Funds, Research of Forest Genetics and Breeding, Kempe Foundation and by the Research School of Forest Genetics at the Swedish University of Agriculture, SLU.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Balocchi CE, Bridgwater FE, Zobel BJ, Jahromi S. Age trends in genetic-parameters for tree height in a nonselected population of loblolly-pine. For Sci. 1993;39:231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Yandell BS, Yi N. Bayesian quantitative trait loci mapping for multiple traits. Genetics. 2008;179:2275–2289. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney GE. Regressive logistic models for familial disease and other binary traits. Biometrics. 1986;42:611–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Kim K, Kim YJ, Lee J-K, Cho YS, Lee J-Y, et al. Joint identification of multiple genetic variants via elastic-net variable selection in a genome-wide association analysis. Ann Hum Genet. 2010;74:416–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner PJ, Brown SK, Weeden NF. Molecular-marker analysis of quantitative traits for growth and development in juvenile apple trees. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;96:1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Durel CE. Time trends in genetic control over height and diameter in maritime pine. Can J For Res. 1996;26:1209–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Coster A, Bastiaansen JWM, Calus MPL, Maliepaard C, Bink MCAM. QTLMAS 2009: simulated dataset. BMC Proc. 2010;4 (Suppl 1:53. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-4-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danjon F. Heritabilities and genetic correlations for estimated growth curve parameters in maritime pine. Theor Appl Genet. 1994;89:911–921. doi: 10.1007/BF00224517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druet T, Georges M. A hidden Markov model combining linkage and linkage disequilibrium information for haplotype reconstruction and quantitative trait locus fine mapping. Genetics. 2010;184:789–798. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.108431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss EJ, Radulovic D, Shaffer SA, Ruderfer DM, Bedalov A, Goodlett DR, et al. Genetic basis of proteome variation in yeast. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo MAT. Adaptive sparseness for supervised learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2003;25:1150–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Wei M, Fabrizio P, Hu J, Cheng C, Longo VD, et al. Comparative analyses of time-course gene-expression profiles of the long-lived sch9Δ mutant. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:143–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee C, Morrison JL, Thomas DC, Gauderman WJ. Segregation and linkage analysis for longitudinal measurements of a quantitative trait. BMC Genetics. 2003;4 (Suppl 1:S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-S1-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianola D, Sorensen D. Quantitative genetic models for describing simultaneous and recursive relationships between phenotypes. Genetics. 2004;167:1407–1424. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.025734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaze D. Optimum selection age for height in shortleaf pine. New Forests. 2009;37:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gwaze DP, Bridgwater FE, Williams CG. Genetic analysis of growth curves for a woody perennial species, Pinus taeda L. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105:526–531. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsen M, Odegard J, Olsen D, Vangen O, Ranberg IMA, Meuwissen THE. Prediction of genetic growth curves in pigs. Animal. 2009;3:475–481. doi: 10.1017/S1751731108003807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner EL, Sorrels ME, Jannink JL. Genomic selection for crop improvement. Crop Sci. 2009;49:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Heuven HCM, Janss LLG. Bayesian multi-QTL mapping for growth curve parameters. BMC Proc. 2010;4 (Suppl 1:S12. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-4-s1-s12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoti F, Sillanpää MJ. Bayesian mapping of genotype × expression interactions in quantitative and qualitative traits. Heredity. 2006;97:4–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson G, Jonsson A, Eriksson G. Use of trait combinations for evaluating juvenile-mature relationships in Picea abies (L) Tree Genet Genomes. 2005;1:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson G, Li B, Hannrup B. Time trends in genetic parameters for height and optimal age for aprental selection in Scots pine. For Sci. 2003;49:696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys H.1961Theory of Probability3rd edn.Claredon Press Oxford: UK [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Zeng Z-B. Multiple trait analysis of genetic mapping for quantitative trait loci. Genetics. 1995;140:1111–1127. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya Z, Sewell MM, Neale DB. Identification of quantitative trait loci influencing annual height- and diameter-increment growth in loblolly pine (Pinus teada L. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98:586–592. [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal S, Gasbarra D, Kinra S, Ebrahim S, Sillanpää MJ. Estimation of additive genetic and environmental sources of quantitative trait variation using data on married couples and their siblings. Genet Res. 2008;90:269–279. doi: 10.1017/S0016672308009348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth CC. Juvenile-mature correlations in Pinaceae and implications for early selection. For Sci. 1980;26:571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, van der Werf JHJ, Hayes BJ, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. Predicting unobserved phenotypes for complex traits from whole-genome SNP data. PloS Genet. 2008;4:e1000231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerceteau E, Szmidt AE, Andersson B. Detection of quantitative trait loci in Pinus sylvestris L. across years. Euphytica. 2001;121:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Altman RB. Finding haplotype tagging SNPs by use of principal component analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:850–861. doi: 10.1086/425587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzana RE, Bernando R. Accuracy of genotypic value prediction for marker-based selection in biparental plant populations. Theor Appl Genet. 2009;120:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan Y, Li H. Model-based method for identifying periodically expressed genes based on time course microarray gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:332–339. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund M, Sorensen P, Madsen P, Jaffrézic F. Detection and modelling of time-dependent QTL in animal populations. Genet Sel Evol. 2008;40:177–194. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-40-2-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Walsh B. Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ma CX, Casella G, Wu RL. Functional mapping of quantitative trait loci underlying the character process: a theoretical framework. Genetics. 2002;161:1751–1762. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.4.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma CX, Lin M, Littell RC, Yin T, Wu RL. A likelihood approach for mapping growth trajectories using dominant markers in a phase-unknown full-sib family. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;108:699–705. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor S, Knott SA, White I, Visscher PM. Quantitative trait locus analysis of longitudinal trait data in complex pedigrees. Genetics. 2005;171:1365–1376. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen S, Kremer A. Selection for an optimum tree growth curve. Silvae Genet. 1993;42:322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Revs Genet. 2010;11:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Thorgaard G, Robison B, Sillanpää MJ. An application of Bayesian QTL mapping to early development in double haploid lines of rainbow trout including environmental effects. Genet Res. 2005;86:209–221. doi: 10.1017/S0016672305007871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen THE, Hayes BJ, Goddard ME. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker map. Genetics. 2001;157:1819–1829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min L, Yang R, Wang X, Wang B. Bayesian analysis of genetic architecture of dynamic traits. Heredity. 2011;106:124–133. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara RB, Sillanpää MJ. Review of Bayesian variable selection methods: what, how and which. Bayesian Anal. 2009;4:85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pikkuhookana P, Sillanpää MJ. Correcting for relatedness in Bayesian models for genomic data association analysis. Heredity. 2009;103:223–237. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piyasatian N, Fernando RL, Dekkers JCM. Genomic selection for marker-assisted improvement in line crosses. Theor Appl Genet. 2007;115:665–674. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0597-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher SD, Geyer C. The genetic analysis of age-dependent traits: modeling the character process. Genetics. 1999;153:825–835. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomion C, Durel CE, O'Malley DM. Genetic dissection of height in maritime pine seedlings raised under accelerated growth conditions. Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93:849–858. doi: 10.1007/BF00224085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Xu S. Quantitative trait associated microarray gene expression data analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1558–1573. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis BY, Butte AS, Kohane IS. Extracting knowledge from dynamics in gene expression. J Biomed Inform. 2001;34:15–27. doi: 10.1006/jbin.2001.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C, Casella G.2004Monte Carlo Statistical Methods2nd edn.Springer-Verlag: New York [Google Scholar]

- Servin B, Stephens M. Imputation-based analysis of association studies: candidate regions and quantitative traits. PloS Genet. 2007;3:e114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää MJ. On statistical methods for estimating heritability in wild populations. Mol Ecol. 2011;20:1324–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää MJ, Arjas E. Bayesian mapping of multiple quantitative trait loci from incomplete inbred line cross data. Genetics. 1998;148:1373–1388. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää MJ, Arjas E. Bayesian mapping of multiple quantitative trait loci from incomplete outbred offspring data. Genetics. 1999;151:1605–1619. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää MJ, Noykova N. Hierarchical modeling of clinical and expression quantitative trait loci. Heredity. 2008;101:271–284. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter D, Thomas A, Best N, Lunn D.2005WinBugs User ManualVersion 2.10MRC Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Public Health: Cambridge, UK [Google Scholar]

- Tholon P, de Queiroz SA. Mathematic models applied to describe growth curves in poultry applied to animal breeding. Ciencia Rural. 2009;39:2261–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaegen D, Plomion C, Gion JM, Poitel M, Costa P, Kremer A. Quantitative trait dissection analysis in Eucalyptus using RAPD markers: 1. Detection of QTL in interspecific hybrid progeny stability of QTL expression across different ages. Theor Appl Genet. 1997;95:597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, et al. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Andersson B, Waldmann P. Genetic analysis of longitudinal height data using random regression. Can J For Res. 2009;39:1939–1948. [Google Scholar]

- West GB, Brown JH, Enqvist BJ. A general model for ontogenetic growth. Nature. 2001;413:628–631. doi: 10.1038/35098076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RL, Ma CX, Chang M, Littell RC, Wu SS, Yin TM, et al. A logistic mixture model for characterizing genetic determinants causing differentiation in growth trajectories. Genet Res. 2002;79:235–245. doi: 10.1017/s0016672302005633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RL, Ma CX, Min L, Casella G. A general framework for analyzing the genetic architecture of developmental characteristics. Genetics. 2004;166:1541–1551. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.3.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RL, Ma CX, Yhang M, Chang M, Littell RC, Santra U, et al. Quantitative trait loci for growth trajectories in Populus. Genet Res. 2003;81:51–64. doi: 10.1017/s0016672302005980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu RL, Lin M. Functional mapping - how to map and study the genetic architecture of dynamic complex traits. Nat Revs Genet. 2006;7:229–237. doi: 10.1038/nrg1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X-L, Heringstad B, Gianola D. Bayesian structural equation models for inferring relationships between phenotypes: a review of methodology, identifiability, and applications. J Anim Breed Genet. 2010;127:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2009.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S. Estimating polygenic effects using markers of the entire genome. Genetics. 2003;163:789–801. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Tian Q, Xu S. Mapping quantitative trait loci for longitudinal traits in line crosses. Genetics. 2006;173:2339–2356. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Xu S. Bayesian shrinkage analysis of quantitative trait loci for dynamic traits. Genetics. 2007;176:1169–1185. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.064279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi N, Shriner D, Banerjee S, Mehta T, Pomp D, Yandell BS. An efficient Bayes model selection approach for interacting quantitative trait loci models with many effects. Genetics. 2007;176:1865–1877. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi N, Xu S. Bayesian LASSO for quantitative trait loci mapping. Genetics. 2008;179:1045–1055. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]