Abstract

TLR2 activation plays a crucial role in Neisseria gonorrhoeae-mediated enhancement of HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells. We examined signaling pathways involved in the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2. TLR2 but not IL-2 signals promoted HIV nuclear import; however, both signals were required for the maximal effect. Although TLR2 signaling could not activate T cells, it increased IL-2-induced T cell activation. Cyclosporin A (CsA) and IkBa inhibitor blocked TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import. PI3K inhibitor blocked HIV infection/nuclear import and T cell activation, and exerted a moderate inhibitory effect on cell cycle progression in CD4+ T cells activated by TLR2/ IL-2. Blockade of p38 signaling suppressed TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import/ infection. However, the p38 inhibitor did not have a significant effect on T cell activation nor TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import. The cell cycle arresting reagent aphidicolin (APH) blocked TLR2- and TCR/CD3-induced HIV infection/ nuclear import. Finally, CsA and IκBα and PI3K inhibitors but not the p38 inhibitor blocked TLR2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation. Our results suggest that TLR2 activation enhances HIV infection/nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells through both T cell activation dependent and independent mechanisms.

Introduction

Sexual transmission is the most common route of HIV infection, and the concurrent presence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is known to increase the likelihood of HIV transmission (1-4). Pathogens for bacterial STIs including Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonococcus, GC) activate TLR2 and TLR4 (5-7), which function as sensors of microbial infection and are critical for the initiation of innate immune responses and may lead to enhanced HIV transmission (8-10). Thus, understanding how TLR activation, triggered by STIs, modulates HIV infection is vital for the development of new strategies to prevent HIV transmission.

Resting CD4+ T cells are one of the earliest targets during heterosexual transmission of HIV/SIV in the genital mucosa (11). We have recently reported that TLR2 but not nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 or TLR4 contributes to the HIV enhancing effect of GC in resting CD4+ T cells (7). Additionally, GC and several TLR2 agonists activate T cells, induce surface HIV co-receptors, and increase HIV infection by facilitating nuclear import (7). The maximal HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 activation is observed when HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells are exposed to TLR2 agonists during early stages of the HIV life cycle (7). While TLR2 agonists activate quiescent naïve and memory CD4+ T cells and enhance HIV infection (12), the underlying molecular mechanism is not well defined.

TLR activation leads to a cascade of signaling events and gene activation (13, 14). For example, TLR2 agonists bind to TLR2/TLR1 or TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers, recruit adaptor proteins such as MyD88 and Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor-containing adapter protein, and lead to activation of specific protein kinases such as MAPK, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, IκB kinase, and PI3K (10, 15). Specific kinases activate certain transcription factors including NF-κB and AP-1 (9, 10, 13, 15). Because HIV has a complex life cycle in which viral proteins closely interact with the host regulatory networks, the network of cellular signals can affect every step of the HIV life cycle (16-19).

In addition to sensing pathogens in innate immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages (10), TLR2 plays an important role in T cell functions (20). TLR2 agonists trigger Th1 effector activities including IFNγ production and cell proliferation (21). TLR2 serves as a co-stimulatory receptor for antigen-specific T cell development and participates in the maintenance of memory T cells (22). TLR2 also modulates the suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (20). TLR2 deficiency results in increased Th17 immunity associated with diminished expansion of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells (23, 24). Both Treg and Th17 are important for HIV pathogenesis (25-27). Thus, by modulating T cell functions, TLR2 may play a role not only in STI-mediated enhanced HIV transmission, but also in HIV pathogenesis.

To understand the underlying molecular mechanisms of TLR2-mediated HIV enhancement, we examined signaling pathways involved in HIV infection, HIV nuclear import, and T cell functions including T cell activation and cell cycle progression in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 or TCR/CD3 activation. We specifically focused on the NF-κB, p38, and PI3K signaling pathways, which are well known to modulate CD4+ T cell function in response to TLR2 activation. We found that TLR2 activation promoted HIV nuclear import in both T cell function independent and dependent manners. The promotion of HIV infection by TLR2 in resting CD4+ T cells required an IL-2 signal and was associated with T cell activation and cell cycle progression. Pathways sensitive to IκBα/NF-κB inhibitor and CsA were involved in TLR2-mediated nuclear import in the absence of IL-2 and independent of T cell function. Pathways sensitive to IκBα/NF-κB inhibitor and CsA were involved, as well, in steps of nuclear import and HIV infection that are associated with T cell functions in response to TLR2/IL-2. While PI3K was involved in TLR2 and TCR/CD3-mediated HIV infection/nuclear import as well as T cell activation, the PI3K inhibitor exerted a moderate effect on cell cycle progression. Interestingly, p38 activation was important for TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import and T cell functions, but played a negligible role in TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection, T cell activation, and cell cycle progression. Our results provided insight into specific signaling pathways in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection in resting CD4+ T cells that is associated with, or independent of, T cell functions, which may allow us to develop strategies for targeting STI-induced pathways without affecting T cell functions.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Recombinant human IL-2, mouse anti-human CD3 Ab (clone UCHT1) and mouse anti-human CD28 Ab (clone 37407.111) were purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). APH, Histopaque®-1077, RPMI-1640 medium and CsA were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). The synthetic TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4, IκBα phosphorylation inhibitor BAY11-7082, p38 inhibitor SB203580, and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 were from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD25 (clone M-A251) and FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD69 (clone FN50) were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA).

Cell culture

PBMCs from normal healthy donors were isolated over Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation. CD4+ T cells were then negatively selected from PBMCs using a CD4+ T cell isolation kit from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA) or StemCell Technologies (Vancouver, Canada), and cultured overnight in RPMI-1640 media with 10% FBS without IL-2 at 37°C. CD25+, CD69+, and HLA-DR+ cells were further depleted by tetrameric antibody complexes (StemCell Technologies). Primary resting CD4+ T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media with 10% FBS and 50 IU/mL IL-2 unless otherwise described.

HIV-1 infection assay

Pseudotyped HIV-1VSV-G luciferase reporter viruses were produced as described previously (28, 29). Primary CD4+ T cells (1 × 106 cells per sample) were infected with pseudotyped HIV-1VSV-G luciferase reporter virus at 37°C for 2 h. After washing off unbound viruses, infected cells were treated with TLR2 agonist Pam3CSK4 at 5 μg/mL in the presence of IL-2 at 37°C for 4 days. Cells were then lysed with lysis buffer (Promega, Madison WI), and luciferase activity (in relative light units [RLUs]) was measured on a Glomax 20/20 luminometer (Promega).

FACS analysis for T cell activation

Cells (1 × 106 cells per sample) were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs specific for T cell activation markers CD25 or CD69. Isotype-matched mAbs conjugated with PE or FITC were used as negative controls. Results were acquired with CellQuest software (BD) on a FACScalibur (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland OR).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were fixed overnight with cold ethanol at -20°C. After two washes with PBS, the fixed cells were stained with 0.5 mL propidium iodide/RNase staining buffer (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark before FACS analysis. The data were analyzed using FlowJo. Doublets of diploid G0/G1 cells were excluded using fluorescence pulse processing signals in dot plots of width versus area (30).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of HIV-1 DNA

Total DNA was extracted from HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA). The level of HIV reverse transcription (RT) products was determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Each PCR reaction contained total DNA, primers (0.2 μM each), and SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen). The primer sequences for HIV-1 late RT products were: R/gag forward, M667 (5′-GGCTAACTAGGGAACCCACTG-3′); R/gag reverse, M661 (5′-CCTGCCTCGAGAGAGCTCCACACTGAC-3′).(31) β-actin was amplified to normalize DNA input; the primer sequences were: actin forward (5′-TGCGTGACATTAAGGAGAAG-3′), actin reverse (5′-GCTCGTAGCTCTTCTCCA-3′). In every experiment, a standard curve for late RT products was generated with serial dilution of pNL4-3.Luc R-E- ranging from 101 to 108 copies. PCR cycling conditions included a 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s. Reactions were carried out and analyzed using the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). The level of HIV-1 closed 2-long terminal repeat (c2-LTR) circles was determined by using primers LR31 (5’-CTTGCCTTGAGTGCTTCAAG-3’) and LR32 (5’-TGCCAATCAGGGAAGTAGCC-3’) (32). Plasmid pTA2LTR(33) was used to generate the standard curve for c2-LTR circles.

Detection of Phospho-IκBα (Ser32)

IκBα phosphorylation was determined with the use of PathScan® Phospho-IκBα (Ser32) sandwich ELISA kit from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Primary resting CD4+ T cells (5 × 106 cells per sample) were treated with medium, IL-2, Pam3CSK4, or Pam3CSK4/IL-2 for 10 min at 37°C, then transferred to ice immediately. After centrifugation, cells were lysed with lysis buffer supplemented with 1mM PMSF for 15 min on ice. The phosphorylation level of phospho-IκBα in the supernatant was determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Differences between data sets were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t test unless otherwise described. A 0.05 or lower p-value is considered to be statistically significant.

Results

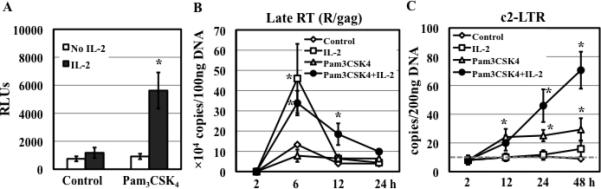

IL-2 and Pam3CSK4 promote HIV infection at different steps of the HIV life cycle in resting CD4+ T cells

We have previously shown that the enhancement of HIV infection by TLR2 activation in resting CD4+ T cells is IL-2 dependent (Fig. 1A) (7). To delineate the impact of TLR2 activation in the presence or absence of IL-2 on the specific early stages of the HIV life cycle after viral entry, total DNA was isolated from HIV-infected primary resting CD4+ T cells that had been exposed to medium, IL-2, Pam3CSK4, or both at different time points after infection. The levels of late RT products and c2-LTR circles, a marker for HIV nuclear import, were determined by real-time PCR analysis. In agreement with previous report (34), IL-2 alone promoted HIV RT (Fig.1B). Pam3CSK4 did not exert any significant effect on HIV RT nor further promoted IL-2-mediated HIV RT. Interestingly, Pam3CSK4 alone, but not IL-2 alone, enhanced HIV nuclear import, and co-stimulation with IL-2 and Pam3CSK4 further increased the level of c2-LTR circles (Fig.1C).

Figure 1. IL-2 is required for the maximal HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 activation.

(A) Primary resting CD4+ T cells were infected with pseudotyped HIV-1VSV-G luciferase reporter virus and then treated with medium (control) or Pam3CSK4 (5 μg/mL) in the presence or absence of IL-2. HIV infection was determined by measuring luciferase activity at day 4 after infection. The difference between samples treated with Pam3CSK4 in the presence or absence of IL-2 is significant (*P<0.05). (B-C) HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with medium (control) or Pam3CSK4 in the presence or absence of IL-2. Total DNA was prepared at indicated time points after infection. The levels of HIV-1 late RT (R/gag) products (B) and c2-LTR circles (C) were determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The detection limit (gray dashed line in panel C) for c2-LTR circles was 10 copies per 200 ng total DNA. There is a difference in the level of RT products between control samples and those treated with IL-2 alone or with Pam3CSK4 and IL-2 (*P<0.05). The difference in the level of c2-LTR circles between control samples and those treated with Pam3CSK4 or with Pam3CSK4 and IL-2 is significant. Results presented are means ± SD of triplicate sample and represent 3 independent experiments.

We and others have shown that TLR2 activation induces increases in the levels of cell surface T cell activation markers and HIV co-receptors (7, 12). Because T cell activation can promote HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells, we determined the effect of specific stimuli including IL-2, Pam3CSK4, or both on T cell activation. FACS analysis of cell surface T cell activation markers, CD25 and CD69, revealed that IL-2 but not Pam3CSK4 induced T cell activation. Interestingly, stimulation of cells with both IL-2 and Pam3CSK4 significantly increased the levels of T cell activation markers (Table 1). These results indicate that IL-2 and Pam3CSK4 differentially affected HIV RT, nuclear import, and T cell activation. However, the presence of both IL-2 and TLR2 signals were required to achieve the maximal effect of TLR2 activation on HIV infection, nuclear import, and T cell activation.

Table 1.

Effect of IL-2 and TLR2 signal on T cell activation and cell cycle progression

| T cell activation |

Cell cycle progression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD25 | CD69 | G0/G1 | S + G2/M | |

| Control | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 99.4 ± 1.4 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| IL-2 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.1* | 96.3 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 1.2* |

| Pam3CSK4 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 98.1 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.9 |

| Pam3CSK4+IL-2 | 8.5 ± 1.5* | 17.9 ± 0.1* | 93.7 ± 2.1* | 5.7 ± 1.9* |

significant difference compared to the control (P<0.05).

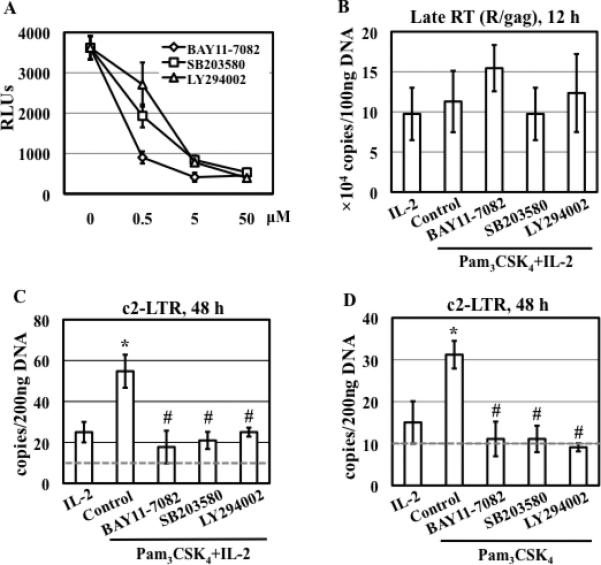

IκBα/NF-kB, p38 and PI3K signaling pathways are involved in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells

Contributions of the NF-κB, p38, and PI3K signaling pathways in TLR2-mediated CD4+ T cell function are well known (35, 36). To assess the roles of NF-κB, p38, and PI3K signaling pathways in the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 activation, HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with specific kinase inhibitors for IκBα (Bay11-7082), p38 (SB203580), and PI3K (LY294002) for 1 hour before stimulation with Pam3CSK4/IL-2. Inhibitors were added back during TLR2 activation. All tested kinase inhibitors blocked TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The IκBα inhibitor, Bay11-7082, at 0.5 μM suppressed greater than 90% of HIV infection and at concentrations of 5 and 50 μM completely blocked HIV infection. The p38 kinase inhibitor, SB203580, at concentrations of 0.5, 5, and 50 μM inhibited HIV infection by 56%, 90% and 100%, respectively. The PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, at concentrations of 0.5, 5, and 50 μM suppressed HIV infection by 22%, 95%, and 100%, respectively. The cytotoxicity of kinase inhibitors was also measured and presented as live cell luminescence in Fig. S1. Although BAY11-7082 at 5 and 50 μM exerted slight to moderate cytotoxicity (12% and 24% reduction of live cell luminescence, respectively), the degree of cytotoxicity of BAY11-7082 could not be completely attributed to HIV inhibition seen in Fig. 2A. SB203580 and LY294002 did not cause any cytotoxic effects indicating that HIV inhibition by SB203580 and LY294002 was not due to inherent cytotoxicity.

Figure 2. Kinase specific inhibitors block TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells.

(A) HIV-infected primary resting CD4+ T cells were treated with kinase specific inhibitors at various concentrations for 1 h before stimulation with Pam3CSK4 and IL-2 (in the continued presence of inhibitors). HIV infection was determined by measuring luciferase activity at day 4 after infection. (B) HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with inhibitors (15 μM) for 1 h and then stimulated with Pam3CSK4 and IL-2. The level of HIV-1 late RT products was analyzed 12 h after infection. There is no difference in the levels of late RT products between samples with or without exposure to inhibitors (P>0.05). (C) HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with inhibitors (15 μM) for 1 h followed by stimulation with Pam3CSK4 and IL-2 for 48 h. The level of c2-LTR circles was measured by real-time PCR analysis. There is a significant difference between samples with treatment of IL-2 and of Pam3CSK4/IL-2 (*P<0.05) as well as between cells with treatment of Pam3CSK4 /IL-2 in the presence or absence of inhibitors (#P<0.05). (D) HIV-infected resting CD4+ T cells were treated with inhibitors (15 μM) for 1 h followed by stimulation with Pam3CSK4 in the absence of IL-2 for 48 h. The level of c2-LTR circles was determined. There is a significant difference between samples treated with Pam3CSK4 and those in media alone or in the presence of IL-2 (*P<0.05). There is a difference between samples with treatment of Pam3CSK4 in the presence or absence of inhibitors (#P<0.05). Data presented are means ± SD of triplicate sample and represent 3 independent experiments.

We then assessed the effect of kinase inhibitors on HIV RT and nuclear import in TLR2-activated resting CD4+ T cells in the presence of IL-2. No significant difference in the level of late RT products was observed in TLR2-activated resting CD4+ T cells in the presence or absence of inhibitors (Fig. 2B). In contrast, TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import was blocked by BAY11-7082, SB203580, and LY294002 (Fig. 2C). As Pam3CSK4, but not IL-2, alone was sufficient to induce HIV nuclear import but not T cell activation in resting CD4+ T cells, we assessed the effect of inhibitors on HIV nuclear import in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells in the absence of IL-2. We found that these kinase-specific inhibitors blocked induction of HIV nuclear import by TLR2 signal alone (Fig. 2D). Taken together, IκBα/NF-κB, p38, and PI3K signaling pathways were involved in both T cell activation-independent (ie, in the absence of IL-2) TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import as well as T cell activation-dependent (ie, in the presence of IL-2) enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import induced by TLR2 in resting CD4+ T cells.

p38 signaling pathway is involved in TLR2- but not TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells

To compare the mechanisms of TLR2- and TCR-mediated HIV enhancement, various conditions for TCR activation including high and low concentrations of immobilized anti-CD3 antibodies in the presence or absence of anti-CD28 antibodies were established (Fig. S2B). Activation of T cells with immobilized anti-CD3 Ab at a low concentration (1 μg/mL) in the presence of IL-2 led to a similar degree of HIV enhancing effect compared to resting CD4+ T cells stimulated with Pam3CSK4 (Fig. S2A). Therefore, TCR/CD3 activation was used for comparison in subsequent studies.

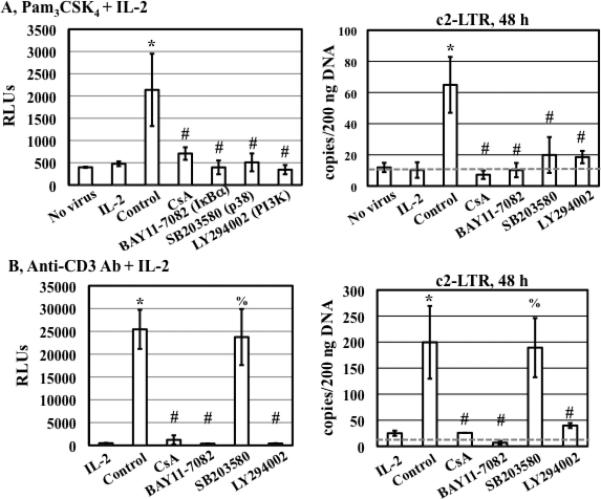

We compared the effect of kinase inhibitors on HIV infection and nuclear import in TLR2- or TCR/CD3-activated CD4+ T cells. In addition to kinase inhibitors, CsA, which blocks multiple stages of the HIV life cycle (34, 37-39) as well as T cell activation (40), was also included as a comparison. The HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 was suppressed by CsA, Bay11-7082, SB203580, and LY294002 (Fig. 3A left panel). Interestingly, TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection was blocked by CsA, Bay11-7082, and LY294002, but not by SB203580 (Fig. 3B left panel). Similarly, all inhibitors blocked TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import (Fig. 3A right panel), whereas all but the p38 kinase inhibitor suppressed TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3B right panel). These results indicated that multiple signaling pathways were involved in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import. Additionally, p38 signaling pathway was specifically involved in TLR2- but not TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. p38 inhibitor SB203580 blocks enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 but not TCR/CD3 activation.

HIV-infected primary resting CD4+ T cells were treated with medium, CsA (1 μg/mL) and specific kinase inhibitors (15 μM) for 1 h before stimulation with either Pam3CSK4 (A) or anti-CD3 Ab at 1 μg/mL (B) in the presence of IL-2. Luciferase activity was measured at day 4 after infection, and the level of c2-LTR circles was determined at 48 h after infection. There is a significant difference between samples with treatment of IL-2 alone or those with Pam3CSK4/IL-2 or anti-CD3 Ab/IL-2 (*P<0.05). The difference between Pam3CSK4/IL-2-treated cells in the presence or absence of inhibitors is significant (#P<0.05). The difference between anti-CD3/IL-2-treated cells in the presence or absence of CsA, BAY11-7082, and LY294002, but not SB203580, is significant (#P<0.05; %P>0.05). The results shown are means ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of results from 3 donors.

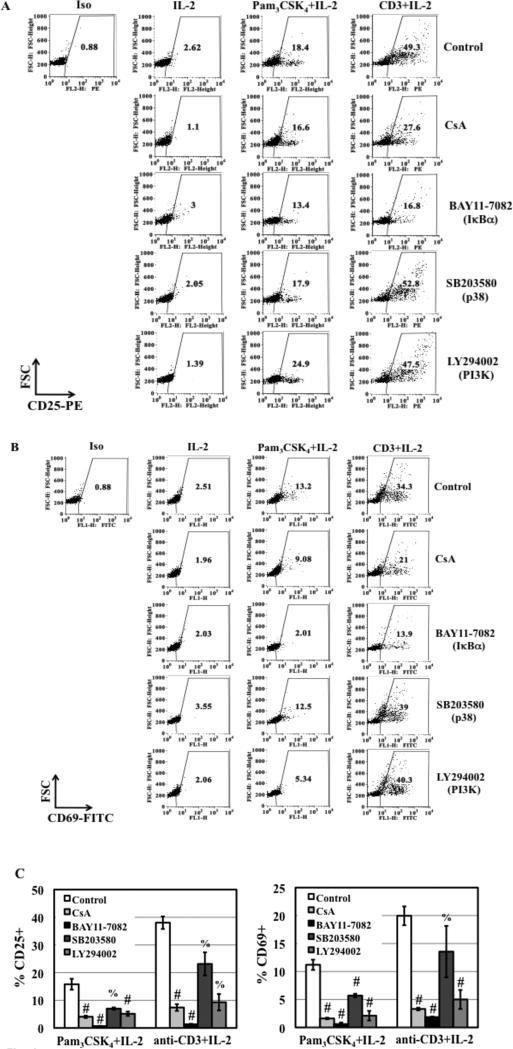

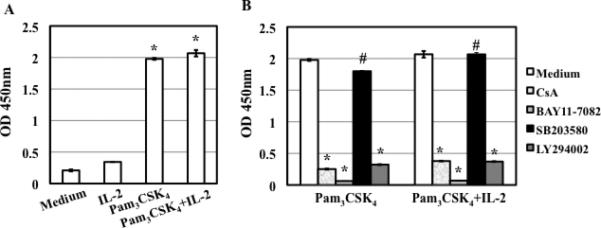

p38 signaling pathway is involved in TLR2- but not TCR/CD3-mediated induction of T cell activation

TLR2 activation increases the level of T cell activation markers (7, 12). To address whether cell signaling pathways involved in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells could also regulate T cell activation, we examined the effect of CsA and kinase inhibitors on TLR2-mediated and TCR/CD3-mediated T cell activation. Overall, the inhibitors at the concentrations (1 μg/mL CsA, 15 μM kinase inhibitors) that were sufficient to block HIV infection exhibited no effect or a moderate inhibitory effect on expression of CD25 and CD69 expression among various donors (Fig. 4A and 4B, and Table S1). However, inhibitors at higher concentrations (eg, 10 μg/mL CsA and 50 μM kinase inhibitors) significantly blocked TLR2-mediated T cell activation (Fig. 4C), although the p38 inhibitor SB203580 at 50 μM only reduced TLR2-mediated induction of CD69 by 50%.

Figure 4. The effect of CsA and kinase specific inhibitors on T cell activation in response to TLR2 and TCR/CD3 activation.

(A and B) Primary resting CD4+ T cells were treated with CsA (1 μg/mL) and kinase specific inhibitors (15 μM) before stimulation with Pam3CSK4 (5 μg/mL)/IL-2 or anti-CD3 Ab (1 μg/mL)/IL-2 for 3 days before analysis of surface expression of CD25 and CD69. Results from other donors were shown in Table S1. (C) The effect of inhibitors at higher concentrations (CsA at 10 μg/mL and kinase specific inhibitors at 50 μM) on T cell activation was determined. Data are presented as the means ± SD of the results from 3 donors. The difference in CD25 and CD69 expression between activated cells in the presence or absence of inhibitors is indicated (#P<0.05) as determined by one tail, paired Student's t test. Compared to the samples in the absence of inhibitors, the p-values for TLR2-treated samples in the presence of the p38 inhibitor SB203580 and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 were 0.068 and 0.03, respectively. There is no significant difference for CD25 and CD69 expression between anti-CD3-activated cells in the presence or absence of SB203580 (%P>0.05, p=0.15 and 0.2 for CD25 and CD69, respectively).

Similar to the results in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells, CsA (1 μg/mL) and BAY11-7082 (15 μM) reduced the expression of CD25 and CD69 in TCR/CD3-activated resting CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4A and 4B). At 15 μM, SB203580 and LY294002 exerted no effect or a moderate inhibitory effect on TCR/CD3-mediated induction of T cell activation markers among various donors (Fig. 4A and 4B, Table S1). CsA, BAY11-7082, and LY294002 at higher concentrations (10 μg/mL, 50 μM, and 50 μM, respectively) significantly blocked induction of T cell activation in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TCR/CD3 activation (Fig. 4C). Note that the inhibition of T cell activation by BAY11-7082 may in part be due to cytotoxicity. Interestingly, high concentrations of SB203580 (50 μM) did not inhibit TCR/CD3-induced T cell activation (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that multiple signaling pathways were involved in TLR2-mediated induction of T cell activation. It is noteworthy, however, that p38 signaling pathway was involved in TLR2- but not TCR/CD3-mediated induction of T cell activation, which coincided with its role in HIV infection in resting CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3).

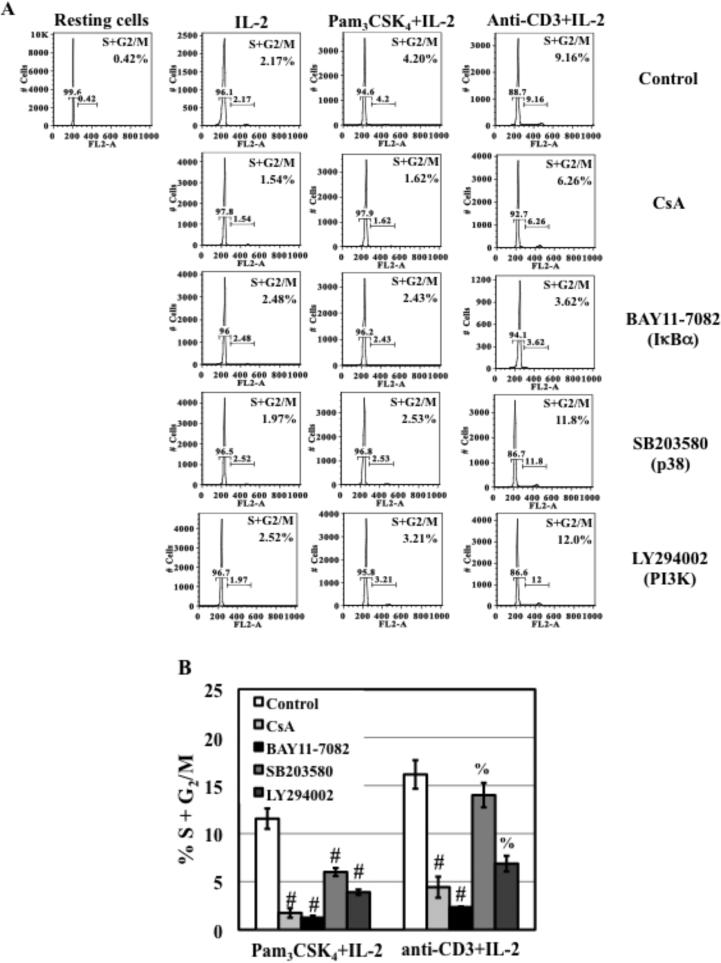

HIV-enhancing effect of TLR2 activation depends on the induction of cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to S and G2/M phases

Cell cycle progression is a key determinant for permissiveness of HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells (41). It is possible that TLR2 activation leads to cell cycle progression, resulting in enhancement of HIV infection of resting CD4+ T cells. To examine the effect of TLR2 activation on cell cycle progression, resting CD4+ T cells were treated with IL-2, Pam3CSK4+IL-2, or anti-CD3 Ab+IL-2 for 72 h. Cells were stained with propidium iodide and DNA content was analyzed by FACS analysis. Initially, more than 99% of resting CD4+ T cells was in G0/G1 phase (Fig. 5A). IL-2 incubation led to 2% of total cells entering S and G2/M phases. TLR2 stimulation without IL-2 did not promote cell cycle progression (Table 1). In the presence of IL-2, TLR2 activation by Pam3CSK4 as well as TCR activation by anti-CD3 Ab further promoted the transition into S and G2/M phases (Fig. 5A; Table 1).

Figure 5. The effect of CsA and kinase inhibitors on cell cycle progression from G0/G1 to S and G2/M phases in response to TLR2 and TCR/CD3 activation.

(A) Primary resting CD4+ T cells were treated with CsA (1 μg/mL), kinase specific inhibitors at 15 μM for 1 h before stimulation with IL-2, anti-CD3 Ab/IL-2, or Pam3CSK4/IL-2. Similar results were obtained from 3 additional donors. (B) The effect of higher concentrations of CsA (10 μg/mL), or kinase specific inhibitors (50 μM) on cell cycle progression in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 and anti-CD3 in the presence of IL-2 was also assessed. Data are presented as means ± SD from 3 different donors. There is a significant difference between TLR2-activated cells in the presence of absence of inhibitors (#P<0.05) as determined by one tail, paired Student's t test. The difference between anti-CD3-activated cells in the presence or absence of SB203580 (p38 inhibitor) and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) is not significant (%P>0.05, p=0.23 and 0.055 for p38 inhibitor and PI3K inhibitor, respectively).

Inhibitors at the concentrations that blocked HIV infection (1 μg/mL CsA and 15 μM kinase inhibitors) did not significantly inhibit IL-2-mediated cell cycle progression (Fig. 5A). In the presence of IL-2, CsA and BAY11-7082 partially blocked TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progression. SB203580 exerted a moderate inhibitory effect on TLR2- but not TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progress. Interestingly, 15 μM LY294002, which blocked both TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and HIV nuclear import, did not significantly suppress cell cycle progression in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 activation or TCR/CD3 activation (Fig. 5A).

High concentrations of CsA (10 μg/mL) and BAY11-7082 (50 μM) significantly blocked TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progression in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 5B). Similar to its effect at 15 μM, 50 μM SB203580 blocked TLR2-mediated cell cycle progression by 50% but did not affect TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progression in the presence of IL-2. A higher concentration of LY294002 (50 μM) suppressed TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progression by approximately 50%.

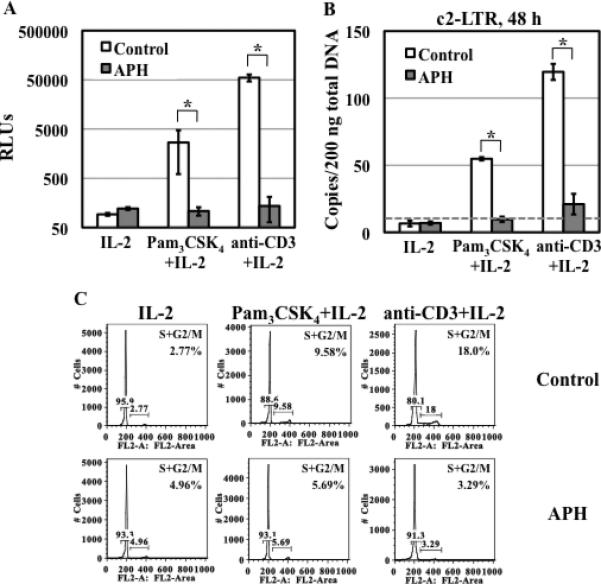

We further assessed the role of cell cycle progression in TLR2-mediated HIV enhancement using APH, a reversible inhibitor for DNA α polymerase, which arrests cells at the G1 and S phase boundary (42, 43). Resting CD4+ T cells were pre-treated with APH for 4 h before HIV exposure followed by TLR2 stimulation. APH treatment was continued during the infection and stimulation. APH at 10 μM completely blocked TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection (Fig. 6A) and HIV nuclear import (Fig. 6B). APH also blocked TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated cell cycle progression by 40% and 82% despite that the inhibitor slightly increased the percentage of IL-2 treated resting CD4+ T cells in S and G2/M phases (Fig. 6C). Cell cycle progression appeared to modulate TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection. Arresting cells at G1/S phases by APH had significant impact on induction of HIV nuclear import by both TLR2 and TCR/CD3.

Figure 6. APH inhibits TLR2- and TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection, but blocks HIV nuclear import induced by TLR2 and TCR/CD3 activation differentially.

(A) Resting CD4+ T cells were treated with APH (10 μM) for 4 h before HIV infection. HIV-infected cells were then stimulated with Pam3CSK4 /IL-2 or anti-CD3 Ab/IL-2 in the presence of APH for 4 days before measuring the luciferase activity. (B) The level of c2-LTR circles was determined at 48 h after infection. (C) Primary resting CD4+ T cells were treated with APH for 4 h and then stimulated with Pam3CSK4/IL-2 or anti-CD3 Ab/IL-2 in the presence of APH for 3 days and the cell cycle was then analyzed. Samples without APH were prepared as a control. There is a significant difference in HIV infection or HIV nuclear import between activated-cells in the presence or absence of APH (*P<0.05). The results shown are means ± SD of triplicate samples and are representative of results from 2 donors.

CsA and inhibitors for IκBa/NF-κB and PI3K but not p38 block TLR2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation in resting CD4+ T cells

TLR2 induces a cascade of signaling events, most notably NF-κB activation, which is controlled by IκBα phosphorylation (10, 44). To examine whether CsA and kinase inhibitors would affect TLR2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation, resting CD4+ T cells were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 hour before stimulation with medium, IL-2, Pam3CSK4, or Pam3CSK4+IL-2 for 10 min. Incubation with IL-2 alone did not induce IκBα phosphorylation, whereas Pam3CSK4 alone or together with IL-2 significantly induced IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 7A). As expected, the IκBα phosphorylation inhibitor, BAY11-7082, completely blocked TLR2-induced IκBα phosphorylation both in the absence and presence of IL-2. Additionally, CsA and LY294002 suppressed IκBα phosphorylation in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 activation with or without IL-2. Interestingly, SB203580 did not exhibit any effect on TLR2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation (Fig. 7B). This result suggested cross-talk between a PI3K and CsA-sensitive pathway and IκBα/NF-κB pathway in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells.

Figure 7. TLR2 activation-induced IκBα phosphorylation is blocked by CsA, BAY11-7082 (IκBα inhibitor) and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), but not SB203580 (p38 inhibitor).

(A) Resting CD4+ T cells were treated with medium, IL-2, Pam3CSK4, or Pam3CSK4/IL-2 for 10 min before measuring the level of IκBα phosphorylation by ELISA. There is a difference between cells with or without TLR2 stimulation (*P<0.05). (B) Resting CD4+ T cells were treated with CsA (1 μg/mL) or kinase specific inhibitors at 15 μM for 1 h before stimulation with Pam3CSK4, or Pam3CSK4/IL-2 for 10 min. There is a significant difference between TLR2-activated cells in the presence or absence of inhibitors (*P<0.05) except for SB203580 (#P>0.05). The results (means ± SD) from duplicate determinations in a single experiment are presented. Similar results were obtained using cells from a different donor.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that IL-2 or TLR2 signal alone differentially promoted HIV RT or nuclear import, although both signals were required to achieve the maximal enhancing effect on HIV infection and nuclear import. While IL-2 signaling, but not TLR2 signaling, induced T cell activation and cell cycle progression, TLR2 activation increased the degree of T cell activation and cycle progression induced by IL-2. Using CsA and kinase-specific inhibitors, we determined that IκBα/NF-κB and CsA-sensitive pathways were important for TLR2- or TCR/CD3-mediated HIV infection and T cell functions. Although PI3K and p38 signaling pathways were involved in the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 activation, blockade of these pathways did not completely abolish TLR2-mediated T cell activation and cell cycle progression, indicating that TLR2 may promote HIV infection through signaling pathways that are independent of T cell functions. In comparison to signaling pathways involved in TCR/CD3 activation, we found that the p38 signaling pathway, which was important for the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2, did not have a significant impact on TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and T cell functions. The effect of these inhibitors on HIV infection, HIV nuclear import, T cell activation and cell cycle progress was summarized in Table 2. Considering all factors, we concluded that multiple signaling pathways were involved in the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2. Some pathways were associated with T cell activation and cell cycle progression but others were independent of these processes.

Table 2.

Summary of the effect of inhibitors on HIV infection, T cell activation and cell cycle progression

| TLR2 activation | TCR/CD3 activation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | T cell | HIV | T cell | |||||||

| Infection | Nuclear import | Activation | Cell cycle | Infection | Nuclear import | Activation | Cell cycle | |||

| CsA | + + + + | + + + + | 1 μg/mL | - | + + | + + + + | + + + + | 1 μg/mL | + | + |

| 10 μg/mL | + + | + + + + | 10 μg/mL | + + + + | + + | |||||

| BAY11-7084d (IκBα) | + + + + | + + + + | 15 μM | + | + | + + + + | + + + + | 15 μM | + + | + + |

| 50 μM | + + + + | + + + + | 50 μM | + + + + | + + + + | |||||

| SB203580 (p38) | + + + + | + + + + | 15 μM | – | + | – | – | 15 μM | – | – |

| 50 μM | + + | + | 50 μM | + | – | |||||

| LY294002 (PI3K) | + + + + | + + + + | 15 μM | – | – | + + + + | + + + + | 15 μM | – | – |

| 50 μM | + + | + + | 50 μM | + + + + | + + | |||||

Inhibition: –, 0-25%; +, 25-50%; ++, 50-75%; ++++, 75-100%. CsA at 1 μg/mL and kinase inhibitors at 5 μM were Used in HIV infection assay. Results of CD25 expression were used to represent T cell activation.

We have previously demonstrated that TLR2 activation promotes early steps in HIV infection such as nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells (7). In this study, we found that TLR2 activation alone, in the absence of IL-2, enhanced nuclear import (Fig. 1C), a finding that differs from a previous report indicating that TCR/CD3 activation required IL-2 or CD28 ligation to promote HIV nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells (34). Unlike TLR2 activation, CD28 ligation alone was not able to promote HIV nuclear import (34). In activated CD4+ T cells, TLR2 can act as a costimulatory molecule and stimulate cytokine production (22, 45). In resting CD4+ T cells, we found that TLR2 alone was not sufficient to induce T cell function, suggesting that the effect of TLR2 activation on T cell function depends on T cell activation status. Based on these considerations, we conclude that the initial enhancement of HIV nuclear import by TLR2 does not require T cell activation or cell cycle progression. However, induction of T cell function by TLR2 in the presence of IL-2 is required for completion of HIV infection.

CsA inhibits HIV replication through multiple pathways, which involves its binding to cyclophilin A (CypA) and blocking subsequent calcineurin/NF-AT signaling (46), whereas NF-κB is known to play a crucial role in HIV infection by modulating viral transcription (reviewed in (47). In the absence of IL-2, suppression of HIV nuclear import by CsA and IκBα inhibitor (Figs. 2, 3, and S3) is probably not mediated through the conventional role of NF-AT or NF-κB in HIV transcription or T cell function. CypA is known to bind HIV capsid proteins (48) that are interacting with transportin 3 and are undergoing nuclear import (49). We speculate that CsA may block HIV nuclear import through a CypA-dependent pathway in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells. Our result demonstrating that CsA abolishes TLR2-mediated IκBα phosphorylation in primary resting CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7B) suggests that a CsA-sensitive pathway acts upstream of IκBα/NF-κB in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells. Indeed, calcineurin has been shown to stimulate NF-κB activity by modulating IκBα activity in transformed T cells (50). It remains to be determined whether CypA and calcineurin play a role along with IκBα/NF-κB in HIV nuclear import in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells in the absence of IL-2.

In addition to IκBα/NF-κB and CsA-sensitive pathways, we found that p38 and PI3K signaling pathways were involved in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection and nuclear import. Several lines of evidence suggested that the role of p38 signaling pathway in the HIV enhancing effect of TLR2 was unlikely to be associated with T cell functions. First, the p38 inhibitor did not block TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import. Second, p38 inhibitor had little effect on TLR2- or TCR/CD3-mediated induction of T cell activation markers. Third, the inhibitory effect of p38 inhibitor on TLR2- or TCR/CD3-induduced cell cycle progression was moderate. In contrast to the p38 inhibitor, the PI3K inhibitor blocked TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import. Oswald-Richter et al have shown that PI3K inhibitors, including LY294002 and Wortmannin, exert a moderate inhibitory effect on HIV infection of naïve CD4+ T cells in response to TCR activation using anti-CD3 and CD28 antibodies (51). In addition, Wortmannin blocks HIV replication at or before completion of RT in TCR (CD3/CD28)-activated naïve CD4+ T cells in the absence of IL-2. Our results demonstrated that the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, did not affect RT in TLR2-activated resting CD4+ T cells in the presence of IL-2 and significantly suppressed TLR2- or TCR/CD3-mediated enhancement of HIV nuclear import. The difference in the effect of PI3K inhibitors on the specific step of the HIV life cycle may be due to the presence of IL-2, stimulation conditions (e.g TLR2 versus TCR), or the inhibitors (Wortmannin versus LY294002). Interestingly, in contrast to the pronounced effect of the PI3K inhibitor on HIV infection/nuclear import, the effect of PI3K inhibitor on T cell activation and cell cycle progression in TLR2- or TCR/CD3-stimulated CD4+ T cells was moderate. These results suggest that the involvement of PI3K pathway in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import is not associated with T cell activation/cell cycle progression.

The activation state of CD4+ T cells is the major cellular determinant for establishing a productive HIV infection (51, 52). In addition to T cell activation, progression to the G1b phase of cell cycle is required to complete RT in quiescent CD4+ T cells with CD3/CD28 activation (41, 53). Our results showed that IL-2, but not TLR2, alone promoted RT (Fig. 1B) possibly due to the ability of IL-2 to promote cell cycle progression and T cell activation. In response to TLR2 activation, the level of c2-LTR circles was increased at 12 h after infection but remained steady up to 48 h after infection, whereas the level of c2-LTR circles was significantly increased after 12 h infection in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 1C). Compared to IL-2 activation alone, stimulation of both TLR2 and IL-2 further activated T cells and induced cell cycle progression (Table 1), which coincided with an increase in the level of c2-LTR circles in cells stimulated with both IL-2 and TLR2 (Fig. 1C), indicating that the activation state of T cells played a crucial role in the maximal HIV enhancing effect of TLR2. The evidence that APH inhibited HIV infection and HIV nuclear import induced by TLR2 or TCR/CD3 activation further confirmed the importance of cell cycle progression.

Kinase specific inhibitors can serve as useful tools for dissecting the role of signaling molecules in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection in human primary cells, particularly in the early stage of investigation. In initial studies, kinase inhibitors present some advantages over gene silencing because the efficiency of silencing specific genes can be technical challenging in resting CD4+ T cells. However, it is important to be aware of caveats. For example, it is worthy of note that the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 at concentrations 100-500-fold higher than the IC50 value for p38 has been shown to affect activities of other kinases including LCK, GSK3β, and PKBβ in vitro (54, 55). Although SB203580 also modulates activation of ERK1/2 and JNK in specific cell lines in response to certain stimuli (56, 57), it remains to be determined whether SB203580 affects ERK1/2 or JNK in primary resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 activation. Similarly, the kinase inhibitor LY294002 can block in vitro kinase activities of casein kinase 2 and GSK3 in addition to PI3K (54, 55). Nonetheless, we found that inhibitors at low concentrations completely blocked HIV infection and nuclear import but had little to moderate effect on T cell function (Table 2). We are currently investigating whether these inhibitors at low concentrations affect other signaling targets in resting CD4+ T cells in response to TLR2 or TCR activation.

In summary, we demonstrated that multiple signaling pathways were involved in TLR2-mediated enhancement of HIV infection/nuclear import in resting CD4+ T cells. While TLR2 activation was able to promote HIV nuclear import independent of T cell activation and cell cycle progression, the maximal HIV enhancing effect was dependent on the activation state of T cells. As TLR2 plays an important role in STI-mediated enhancement of HIV infection, a better understanding of cellular mechanisms required for HIV infection in TLR2-activated CD4+ T cells will lead to the development of new strategies to prevent HIV transmission.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant R01 AI081559 (T.L.C.).

Abbreviations

- APH

Aphidicolin

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- CypA

cyclophilin A

- c2-LTR

closed 2-long terminal repeat

- GC

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Treg

regulatory T cells

- RT

reverse transcription

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

Footnotes

Authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Miller WC. Sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeficiency virus infection: cause, effect, or both? Int J Infect Dis. 1998;3:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(98)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK, Gakinya MN, Waiyaki P, Cheang M, Piot P, Ronald AR, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:233–239. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, Gakinya MN, Cheang M, Ndinya-Achola JO, Piot P, Brunham RC, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghys PD, Fransen K, Diallo MO, Ettiegne-Traore V, Coulibaly IM, Yeboue KM, Kalish ML, Maurice C, Whitaker JP, Greenberg AE, Laga M. The associations between cervicovaginal HIV shedding, sexually transmitted diseases and immunosuppression in female sex workers in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 1997;11:F85–93. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199712000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prebeck S, Brade H, Kirschning CJ, da Costa CP, Durr S, Wagner H, Miethke T. The Gram-negative bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis L2 stimulates tumor necrosis factor secretion by innate immune cells independently of its endotoxin. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:463–470. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singleton TE, Massari P, Wetzler LM. Neisserial porin-induced dendritic cell activation is MyD88 and TLR2 dependent. J Immunol. 2005;174:3545–3550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding J, Rapista A, Teleshova N, Mosoyan G, Jarvis GA, Klotman ME, Chang TL. Neisseria gonorrhoeae enhances HIV-1 infection of primary resting CD4+ T cells through TLR2 activation. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:2814–2824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MS, Kim YJ. Signaling pathways downstream of pattern-recognition receptors and their cross talk. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:447–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060605.122847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:221–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature immunology. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Schuler T, Zupancic M, Wietgrefe S, Staskus KA, Reimann KA, Reinhart TA, Rogan M, Cavert W, Miller CJ, Veazey RS, Notermans D, Little S, Danner SA, Richman DD, Havlir D, Wong J, Jordan HL, Schacker TW, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Letvin NL, Wolinsky S, Haase AT. Sexual transmission and propagation of SIV and HIV in resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Science. 1999;286:1353–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thibault S, Tardif MR, Barat C, Tremblay MJ. TLR2 signaling renders quiescent naive and memory CD4+ T cells more susceptible to productive infection with X4 and R5 HIV-type 1. J Immunol. 2007;179:4357–4366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blasius AL, Beutler B. Intracellular toll-like receptors. Immunity. 2010;32:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MS, Kim YJ. Signaling Pathways Downstream of Pattern-Recognition Receptors and Their Cross Talk. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060605.122847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Jiang S, Tapping RI. Toll-like receptor signaling in cell proliferation and survival. Cytokine. 2010;49:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauci AS. Host factors and the pathogenesis of HIV-induced disease. Nature. 1996;384:529–534. doi: 10.1038/384529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unutmaz D. T cell signaling mechanisms that regulate HIV-1 infection. Immunol Res. 2001;23:167–177. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graziosi C, Gantt KR, Vaccarezza M, Demarest JF, Daucher M, Saag MS, Shaw GM, Quinn TC, Cohen OJ, Welbon CC, Pantaleo G, Fauci AS. Kinetics of cytokine expression during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4386–4391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfano M, Poli G. Role of cytokines and chemokines in the regulation of innate immunity and HIV infection. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:161–182. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabelitz D. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors in T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imanishi T, Hara H, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Akira S, Saito T. Cutting edge: TLR2 directly triggers Th1 effector functions. J Immunol. 2007;178:6715–6719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komai-Koma M, Jones L, Ogg GS, Xu D, Liew FY. TLR2 is expressed on activated T cells as a costimulatory receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400171101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loures FV, Pina A, Felonato M, Calich VL. TLR2 is a negative regulator of Th17 cells and tissue pathology in a pulmonary model of fungal infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:1279–1290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichols JR, Aldrich AL, Mariani MM, Vidlak D, Esen N, Kielian T. TLR2 deficiency leads to increased Th17 infiltrates in experimental brain abscesses. J Immunol. 2009;182:7119–7130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nixon DF, Aandahl EM, Michaelsson J. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in HIV infection. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1063–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanwar B, Favre D, McCune JM. Th17 and regulatory T cells: implications for AIDS pathogenesis. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010;5:151–157. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328335c0c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elhed A, Unutmaz D. Th17 cells and HIV infection. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010;5:146–150. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833647a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connor RI, Sheridan KE, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau NR. Change in coreceptor use coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1--infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen BK, Saksela K, Andino R, Baltimore D. Distinct modes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral latency revealed by superinfection of nonproductively infected cell lines with recombinant luciferase-encoding viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:654–660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.654-660.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wersto RP, Chrest FJ, Leary JF, Morris C, Stetler-Stevenson MA, Gabrielson E. Doublet discrimination in DNA cell-cycle analysis. Cytometry. 2001;46:296–306. doi: 10.1002/cyto.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zack JA, Arrigo SJ, Weitsman SR, Go AS, Haislip A, Chen IS. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zazzi M, Romano L, Catucci M, Venturi G, De Milito A, Almi P, Gonnelli A, Rubino M, Occhini U, Valensin PE. Evaluation of the presence of 2-LTR HIV-1 unintegrated DNA as a simple molecular predictor of disease progression. J Med Virol. 1997;52:20–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199705)52:1<20::aid-jmv4>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cara A, Cereseto A, Lori F, Reitz MS., Jr. HIV-1 protein expression from synthetic circles of DNA mimicking the extrachromosomal forms of viral DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5393–5397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Y, Pinchuk LM, Agy MB, Clark EA. Nuclear import of HIV-1 DNA in resting CD4+ T cells requires a cyclosporin A-sensitive pathway. J Immunol. 1997;158:512–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanin-Zhorov A, Cahalon L, Tal G, Margalit R, Lider O, Cohen IR. Heat shock protein 60 enhances CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell function via innate TLR2 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2022–2032. doi: 10.1172/JCI28423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.MacLeod H, Wetzler LM. T cell activation by TLRs: a role for TLRs in the adaptive immune response. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:e48. doi: 10.1126/stke.4022007pe48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinoshita S, Chen BK, Kaneshima H, Nolan GP. Host control of HIV-1 parasitism in T cells by the nuclear factor of activated T cells. Cell. 1998;95:595–604. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinoshita S, Su L, Amano M, Timmerman LA, Kaneshima H, Nolan GP. The T cell activation factor NF-ATc positively regulates HIV-1 replication and gene expression in T cells. Immunity. 1997;6:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherry B, Zybarth G, Alfano M, Dubrovsky L, Mitchell R, Rich D, Ulrich P, Bucala R, Cerami A, Bukrinsky M. Role of cyclophilin A in the uptake of HIV-1 by macrophages and T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1758–1763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flanagan WM, Corthesy B, Bram RJ, Crabtree GR. Nuclear association of a T-cell transcription factor blocked by FK-506 and cyclosporin A. Nature. 1991;352:803–807. doi: 10.1038/352803a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korin YD, Zack JA. Progression to the G1b phase of the cell cycle is required for completion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription in T cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3161–3168. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3161-3168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krokan H, Wist E, Krokan RH. Aphidicolin inhibits DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase alpha and isolated nuclei by a similar mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:4709–4719. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.18.4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliere S, Arguello M, Mesplede T, Tumilasci V, Nakhaei P, Stojdl D, Sonenberg N, Bell J, Hiscott J. Vesicular stomatitis virus oncolysis of T lymphocytes requires cell cycle entry and translation initiation. J Virol. 2008;82:5735–5749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02601-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–1525. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu D, Komai-Koma M, Liew FY. Expression and function of Toll-like receptor on T cells. Cell Immunol. 2005;233:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cron RQ. HIV-1, NFAT, and cyclosporin: immunosuppression for the immunosuppressed? DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:761–767. doi: 10.1089/104454901753438570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohr O, Marban C, Aunis D, Schaeffer E. Regulation of HIV-1 gene transcription: from lymphocytes to microglial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:736–749. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0403180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luban J, Bossolt KL, Franke EK, Kalpana GV, Goff SP. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein binds to cyclophilins A and B. Cell. 1993;73:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90637-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krishnan L, Matreyek KA, Oztop I, Lee K, Tipper CH, Li X, Dar MJ, Kewalramani VN, Engelman A. The requirement for cellular transportin 3 (TNPO3 or TRN-SR2) during infection maps to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid and not integrase. Journal of virology. 2010;84:397–406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01899-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frantz B, Nordby EC, Bren G, Steffan N, Paya CV, Kincaid RL, Tocci MJ, O'Keefe SJ, O'Neill EA. Calcineurin acts in synergy with PMA to inactivate I kappa B/MAD3, an inhibitor of NF-kappa B. EMBO J. 1994;13:861–870. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oswald-Richter K, Grill SM, Leelawong M, Unutmaz D. HIV infection of primary human T cells is determined by tunable thresholds of T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1705–1714. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Unutmaz D, KewalRamani VN, Marmon S, Littman DR. Cytokine signals are sufficient for HIV-1 infection of resting human T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1735–1746. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vatakis DN, Nixon CC, Bristol G, Zack JA. Differentially stimulated CD4+ T cells display altered human immunodeficiency virus infection kinetics: implications for the efficacy of antiviral agents. J Virol. 2009;83:3374–3378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02161-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JS, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clerk A, Sugden PH. The p38-MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, inhibits cardiac stress-activated protein kinases/c-Jun N-terminal kinases (SAPKs/JNKs). FEBS Lett. 1998;426:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewthwaite JC, Bastow ER, Lamb KJ, Blenis J, Wheeler-Jones CP, Pitsillides AA. A specific mechanomodulatory role for p38 MAPK in embryonic joint articular surface cell MEK-ERK pathway regulation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11011–11018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.