Abstract

Two anabaenopeptin-type peptides, lyngbyaureidamides A and B, together with two previously reported peptides lyngbyazothrins C and D, were isolated from the cultured freshwater cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91). Their structures were determined by spectroscopic and chemical methods. Lyngbyazothrins C and D were also able to inhibit the 20S proteasome with IC50 values of 7.1 μM and 19.2 μM, respectively, while lyngbyaureidamides A and B were not active at 50 μM.

Keywords: Cyanobacterium, Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91), Peptide, 20S proteasome

1. Introduction

Cyanobacteria are known to be a rich source of secondary metabolites with diverse chemical structures and biological activities (Wagoner et al., 2007; Tan, 2007; Müeller et al., 2006; Luesch et al., 2001; Singh et al., 2005; Jaiswal et al., 2008). Many of these metabolites have been found to inhibit various proteases and we have initiated a screening program to discover cyanobacterial inhibitors of the 20S proteasome, the catalytic core of the major proteolytic system in eukaryotic cells and an established anticancer target. One of the active extracts was Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91), which showed inhibitory activity against the 20S proteasome at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. Bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of four cyclic peptides, including two new anabaenopeptin–type peptides lyngbyaureidamides A (1) and B (2) and the previously reported peptides lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4). Lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4) were originally reported as an inseparable mixture with antibacterial activity from this strain (Zainuddin et al., 2009). Lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4) were recently reported individually as portoamides A and B (Leão et al., 2010).

2. Results and Discussion

Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91) was mass cultured in Z medium (Mian et al., 2003). The organic extract was active in our 20S proteasome assay and was fractionated using a diaion HP20SS resin column. The activity was recovered in fraction 3, eluting with 40% isopropanol in water and further purified by HPLC, which led to the isolation of four peptides: lyngbyaureidamides A (1) and B (2) and the previously reported peptides lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4).

Lyngbyaureidamide A (1) was obtained as a yellowish gum. The molecular formula was determined as C46H61N7O9 by HRMS (m/z 878.4426 [M + Na]+). The proton spectrum of 1 contained signals for six amide protons (δH 8.92, 8.75, 7.13, 7.03, 6.61 and 5.93), a N-methyl group (δH 2.64) and six α-protons (δH 4.95, 4.78, 4.16, 3.95, 3.87 and 3.77). The latter set correlated with six carbon resonances (δC 54.9, 49.0, 53.4, 55.2, 57.3 and 56.1) in the HSQC spectrum. Detailed 2D NMR spectroscopic analysis (Table 1 and Figure 2) indicated the presence of six amino acid residues, three of which were the common amino acids Lys, Ile and Phe. The structures of three remaining non-standard amino acid residues were determined by analysis of COSY, HSQC and HMBC data. The structure of N-MeAla was determined by the HMBC correlation from the N-methyl singlet to the N-MeAla C-1 (δC 170.6), in combination with a COSY correlation between N-MeAla H-α and N-MeAla H3-β (δH 1.25). The presence of a homophenylalanine (Hph) residue was deduced by the HMBC correlation from Hph H2-γ (δH 2.39) to C-2′/C-6′ (δC 128.6) connecting the two partial structures established by COSY correlations (Hph NH to H2-γ and a mono substituted aromatic ring C-1′–C-6′). Similarly, the presence of a homotyrosine (Hty) residue was deduced by the HMBC correlations from Hty H2-γ (δH 2.48 and 2.67) to C-2′/C-6′ (δC 129.5), connecting Hty NH to H2-γ partial structure to the para-substituted aromatic ring (Hty C-1′– C6′).

Table 1.

NMR spectroscopic data (δ) of compounds 1 and 2 in DMSO-d6

| unit | C/H no. | 1 | 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δCa | δHb | COSY | HMBC | δCc | δHb | COSY | HMBC | ||

| Ile1 | NH | 7.03 | Hα | C-1Lys | 7.14 | Hα | C-1Lys | ||

| C-1 | 173.2 | 173.0 | |||||||

| Cα | 57.3 | 3.87 | NH, Hβ | 57.1 | 3.97 | NH, Hβ | |||

| Cβ | 35.9 | 1.54 | Hα, Hγ, H′γ | C-1Ile | 36.1 | 1.77 | Hα, Hγ, H′γ | C-1Ile | |

| Cγ | 25.4 | 1.45 | Hβ, Hδ | 25.3 | 1.56 | Hβ, Hδ | |||

| 1.04 | Hβ, Hδ | 1.17 | Hβ, Hδ | ||||||

| C′γ | 15.5 | 0.89 | Hβ | 15.4 | 1.01 | Hβ | |||

| Cδ | 10.8 | 0.73 | Hγ | 10.7 | 0.82 | Hγ | |||

| Hty2 | NH | 8.92 | Hα | C-1Ile | 8.94 | Hα | C-1Ile | ||

| C-1 | 171.8 | 171.4 | |||||||

| Cα | 49.0 | 4.78 | NH, Hβ | 49.2 | 4.71 | NH, Hβ | |||

| Cβ | 33.8 | 1.93 | Hα, Hγ | C-1Hty | 33.7 | 1.87 | Hα, Hγ | C-1Hty | |

| 1.80 | Hα, Hγ | 1.72 | Hα, Hγ | ||||||

| Cγ | 30.9 | 2.67 | Hβ | C-1′, 2′, 6′ | 31.0 | 2.64 | Hβ | C-1′, 2′, 6′ | |

| 2.48 | Hβ | 2.43 | Hβ | ||||||

| C-1′ | 131.2 | 131.7 | |||||||

| C-2′,6′ | 129.5 | 7.04 | H-3′,5′ | 129.5 | 7.01 | H-3′,5′ | |||

| C-3′,5′ | 115.5 | 6.69 | H-2′,6′ | 115.6 | 6.67 | H-2′,6′ | |||

| C-4′ | 156.0 | 156.0 | |||||||

| 4′-OH | 9.26 | 9.26 | |||||||

| N-MeAla3 | N-Me | 28.8 | 2.64 | C-1NMe-Ala, Cα, C-1Hty | 27.4 | 1.77 | C-1NMe-Ala, Cα, C-1Hty | ||

| C-1 | 170.6 | 170.6 | |||||||

| Cα | 54.9 | 4.95 | Hβ | 54.7 | 4.78 | Hβ | |||

| Cβ | 14.5 | 1.25 | Hα | C-1NMe-Ala | 14.3 | 1.06 | Hα | C-1NMe-Ala | |

| Hph4/Phe4 | NH | 8.75 | Hα | C-1NMe-Ala | 8.75 | Hα | C-1NMe-Ala | ||

| C-1 | 171.5 | 171.5 | |||||||

| Cα | 53.4 | 4.16 | NH, Hβ | 55.4 | 4.35 | NH, Hβ | |||

| Cβ | 34.5 | 2.08 | Hα, Hγ | C-1Hph | 37.9 | 3.29 | Hα | C-1Phe4 and C-1′, 2′, 6′ | |

| 1.90 | Hα, Hγ | 2.78 | Hα | ||||||

| Cγ | 32.3 | 2.39 | Hβ | C-1′, 2′, 6′ | |||||

| C-1′ | 141.9 | 139.1 | |||||||

| C-2′,6′ | 128.6 | 7.07 | 129.3 | 7.05 | |||||

| C-3′,5′ | 128.5 | 7.23 | 128.7 | 7.20 | |||||

| C-4′ | 126.2 | 7.15 | 126.4 | 7.15 | |||||

| Lys5 | NH | 6.61 | Hα | 6.62 | Hα | ||||

| C-1 | 172.9 | 172.9 | |||||||

| Cα | 55.2 | 3.95 | NH, Hβ | CUreido | 55.4 | 3.96 | NH, Hβ | CUreido | |

| Cβ | 32.7 | 1.54 | Hα, Hγ | C-1Lys | 32.7 | 1.59 | Hα, Hγ | C-1Lys | |

| Cγ | 20.7 | 1.26 | Hβ | 20.8 | 1.29 | Hβ | |||

| 1.09 | 1.13 | ||||||||

| Cδ | 28.5 | 1.45 | Hε | 28.5 | 1.48 | Hε | |||

| 1.38 | 1.43 | ||||||||

| Cε | 38.7 | 3.50 | ε-NH, Hδ | 38.8 | 3.56 | ε-NH, Hδ | |||

| 2.79 | ε-NH, Hδ | 2.81 | ε-NH, Hδ | ||||||

| ε-NH | 7.13 | Hε | C-1Hph | 7.16 | Hε | C-1Phe4 | |||

| Phe6 | NH | 5.93 | Hα | 5.96 | Hα | ||||

| C-1 | 173.0 | 173.3 | |||||||

| Cα | 56.1 | 3.77 | NH, Hβ | CUreido | 55.4 | 3.96 | NH, Hβ | CUreido | |

| Cβ | 38.2 | 3.00 | Hα | C-1Phe, and C-1′, 2′, 6′ | 38.2 | 3.01 | Hα | C-1Phe6 and C-1′, 2′, 6′ | |

| 2.94 | Hα | 2.96 | Hα | ||||||

| C-1′ | 140.1 | 139.8 | |||||||

| C-2′,6′ | 130.1 | 7.06 | 130.0 | 7.11 | |||||

| C-3′,5′ | 127.6 | 7.12 | 127.9 | 7.19 | |||||

| C-4′ | 125.6 | 7.07 | 126.0 | 7.14 | |||||

| Ureido | CUreido | 157.1 | 157.3 | ||||||

Chemical shifts were determined by HSQC and HMBC experiments recorded at 600 MHz.

Recorded at 600 MHz.

DEPTQ experiment recorded at 226 MHz.

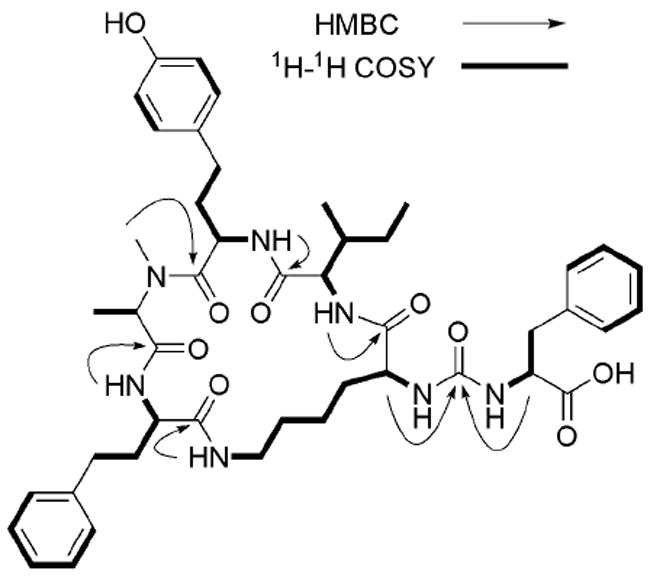

Figure 2.

1H–1H COSY and key HMBC correlations of 1.

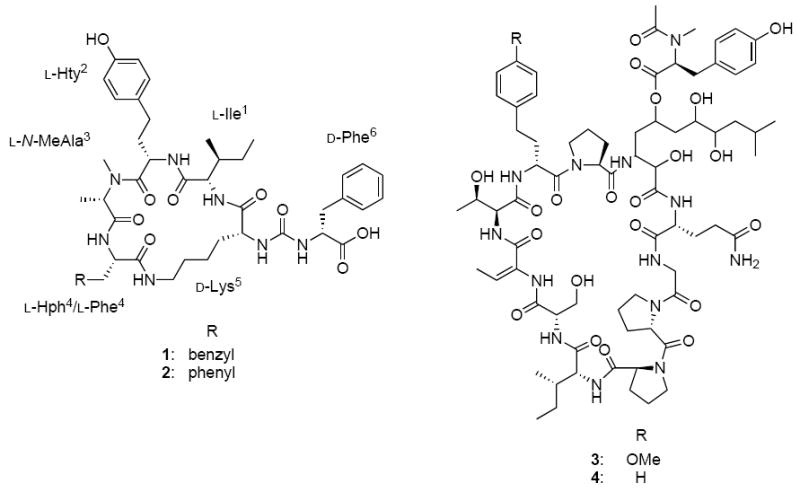

The structure of 1 was established by interpretation of the HMBC spectrum (Table 1 and Figure 2). The correlations from the NH of Hph to C-1 of N-MeAla (δC 170.6), from HNMe- of N-MeAla to C-1 of Hty (δC 171.8), from the NH of Hty to C-1 of Ile (δC 173.2), from the NH of Ile to C-1 of Lys (δC 172.9) and from ε-NH of Lys to C-1 of Hph (δC 171.5), indicated that these five residues formed a 19-membered peptide ring, characteristic of the anabaenopeptin–type peptides (Welker and von Döhren, 2006). Finally, analysis of the correlations from H-α of Lys and H-α of Phe to the same sp2 carbon at δC 157.1 suggested that the remaining Phe residue was attached to the 19-membered ring through an ureido group. This ureido group also accounted for the remaining carbonyl moiety implied by the molecular formula. The absolute configurations of amino acid residues of 1 were determined by Marfey’s method (Marfey, 1984). The result of the HPLC analysis showed that N-MeAla, Hty, Ile and Hph all were of the L configuration, while Lys and Phe both were D.

Lyngbyaureidamide B (2) was obtained as a yellow gum. The HRMS quasimolecular peak at m/z 864.4255 [M + Na]+ suggested a molecular formula of C45H59N7O9. The 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic data of 2 were very similar to those of 1. The only difference was the loss of the Hph moiety and the appearance of an additional Phe moiety in 2. The placement of the second Phe moiety was determined by analysis of the ROESY spectrum of 2. The correlations between NH of Phe4 (δH 8.75) and H-α of N-MeAla3 (δH 4.78) and ε-NH of Lys5 (δH 7.16) indicated that Hph had been replaced by Phe. This was confirmed by the HMBC correlations from the NH of Phe4 to C-1 of N-MeAla3 (δC 170.6), and from ε-NH of Lys5 to C-1 of Phe4 (δC 171.5). The amino acid residues of 2 were defined as L-Ile, L-Hty, L- N-MeAla, L-Phe, D-Phe and D-Lys by Marfey’s method), indicating the replacement of L-Hph4 by L-Phe4. This assignment was further supported by comparison of the NMR spectroscopic data of lyngbyaureidamide B with those published for other anabaenopeptins containing a L-Hty-L-N-MeAla-L-Phe-D-Lys sequence as part of their 19-membered peptide ring (Williams et al., 1996; Zafrir-Ilan et al., 2010). No significant deviation (<0.8 ppm) was found for these 13C chemical shifts. In addition, the NMR chemical shifts for Phe6 of lyngbyaureidamide B closely matched those of Phe6 of 1. Together, this indicated L-Phe to be in position 4.

Anabaenopeptins, a group of cyclic hexapeptides, are characterized by a 19-membered peptide ring that is formed by cyclization between the C-terminal amino acid and the ε-amine of a lysine residue. The α-amine of the lysine is further linked through an ureido group to a side-chain amino acid. Anabaenopeptin–type peptides have been obtained from several cyanobacterial species, including Anabaena (Harada et al., 1995; Grach-Pogrebinsky et al., 2008), Aphanizomenon (Murakami et al., 2000), Lyngbya (Matthew et al., 2008), Microcystis (Williams et al., 1996; Beresovsky et al., 2006; Gesner-Apter et al., 2009; Zafrir-Ilan et al., 2010), Nodularia (Fujii et al., 1997), Oscillatoria (Sano et al., 1995; Shin et al., 1997; Itou et al., 1999), Planktothrix (Sano et al., 2001; Okumura et al., 2009), Schizothrix (Reshef et al., 2002), and Tychonema (Müeller et al., 2006), as well as from sponges (Kobayashi et al., 1991a, 1991b; Schmidt et al., 1997; Uemoto et al., 1998; Robinson et al., 2007; Plaza et al., 2010). The exocylic amino acid for all anabaenopeptin–type peptides reported to date has L configuration and lyngbyaureidamide A (1) and B (2) are the first examples of a D-configuration amino acid residue at this position (D-Phe).

All isolates were evaluated for their 20S proteasome inhibitory activity (chymotrypsin-like activity). Lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4) were found to be active with IC50 values of 7.1 μM and 19.2 μM, respectively, while lyngbyaureidamide A (1) and B (2) were found to be inactive at 50 μM. None of the four compounds showed cytotoxic activities against the human colon cancer cell line designated HT-29 at 50 μM. Lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4) were originally obtained as an inseparable mixture from this cyanobacterial strain and shown to inhibit the growth of E. coli (Zainuddin et al., 2009). The same two structures were recently also reported as pure compounds, named portoamides A and B, obtained from an Oscillatoria sp. (Leão et al., 2010). The portoamides were found to act synergistically to inhibit the growth of the green microalga Chlorella vulgaris. We here were also able to separate lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4), the two major components of Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91) by HPLC. Comparison of the spectroscopic data confirmed that lyngbyazothrins C and D were identical to portoamides A and B, respectively.

3. Conclusions

Bioassay-guided investigation (proteasome inhibition) of the cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91) led to the isolation of four peptides. The previously reported lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4) accounted for the 20S proteasome inhibitory activity. In addition, two new anabaenopeptin–type peptides, lyngbyaureidamide A (1) and B (2) were obtained.

4. Experimental

4.1. General experimental procedures

The optical rotations were determined on a Perkin-Elmer 241 polarimeter. UV spectra were obtained on a Varian Cary 50 Bio spectrophotometer. IR spectra were obtained on a Jasco FTIR-410 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance DRX600 MHz NMR spectrometer with a 5 mm CPTXI Z-gradient probe and a Bruker Avance II900 MHz NMR spectrometer with a 5 mm ATM CPTCI Z-gradient probe, referenced to the corresponding solvent peaks. HRMS spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu IT-TOF spectrometer. HPLC separations were performed on an instrument consisting of a Waters 600 controller, a Waters 600 pump, and a Waters 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector, with an Alltima (250 × 10 mm i.d.) preparative column packed with C18 (5 μm) or a Varian (250 × 10 mm i.d.) semipreparative column packed with C8 (5 μm).

4.2. Biological Material

Lyngbya sp. (SAG 36.91) from Culture Collection of Algae, Göttingen, Germany) was grown in 21 L of aerated inorganic Z media (Mian et al., 2003). Cultures were illuminated with fluorescent lamps at 1.93 klx with an 18/6 h light/dark cycle. The temperature of the culture room was maintained at 22 °C. After 7 weeks, the biomass of cyanobacteria was harvested by centrifugation and freeze-dried (yield 11.24g).

4.3. Extraction and isolation

Freeze-dried Lyngbya biomass (11.24 g) was extracted five times, each for two hrs with 200 ml of CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1) at room temperature to yield a crude extract (984.5 mg). A portion of the crude extract (849.8 mg) was fractionated using a Diaion HP-20 column (10 g, 130 × 25 mm) with increasing amounts of i-PrOH:H2O (0:100; 20:80; 40:60; 70:30; 80:20; 90:10; 100:0, fraction size 100 ml) to generate eight sub-fractions. Fraction 3 (eluted with i-PrOH 40:60, v/v) was the most active fraction and showed 78.4% inhibition against 20S proteasome at 50 μg/mL. This fraction (103.5 mg) was subjected to reversed–phase HPLC (Alltima C18, 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm) with a solvent gradient of MeOH:H2O (35–65→90:10) over 50 min to afford two subfractions (3a at 32-33 min, and 3b at 35-36 min). Subfraction 3a (8.9 mg) was further separated by reversed–phase HPLC (Varian C8, 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm), using MeOH–H2O (55:45) as mobile phase, to yield 1 (1.6 mg, eluting after 112 min) and 2 (1.1 mg eluting after 110 min). Subfraction 3b (67.3 mg) was subjected to reversed–phase HPLC (Varian C8, 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm), eluted by MeOH–H2O (65:35), to give 3 (20.5 mg, eluting after 183 min) and 4 (10.3 mg, eluting after 188 min).

4.3.1 Lyngbyaureidamide A (1)

yellowish gum; [α]D −27.3 (c 0.09 MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.21) nm; IR (neat) νmax 3295, 3250, 2932, 2863, 1643, 1548, 1503, 1452, 1250, 1007 cm-1; For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data, see Table 1; HRMS m/z 878.4426 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C46H61N7O9Na, 878.4428).

4.3.2 Lyngbyaureidamide B (2)

yellow gum; [α]D −41.1 (c 0.06 MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 210 (4.27) nm; IR (neat) νmax 3286, 2928, 1643, 1548, 1524, 1504, 1250, 1024 cm-1; For 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data’ see Table 1; HRMS m/z 864.4255 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C45H59N7O9Na, 864.4272).

4.3.3 Lyngbyazothrin C (3)

yellow gum; [α]D −14.6 (c 0.1 MeOH); IR (neat) νmax 3321, 2957, 1652, 1601, 1506, 1250, 1214 cm-1; 1H and 13C NMR data as described (Zainuddin et al., 2009; Leao et al., 2010); HRMS m/z 1554.7771 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C74H109N13O22Na, 1554.7708).

4.3.4 Lyngbyazothrin D (4)

yellow gum; [α]D −17.2 (c 0.1 MeOH); IR (neat) νmax 3307, 2971, 1664, 1605, 1470, 1207, 1128 cm-1; 1H and 13C NMR data as described (Zainuddin et al., 2009; Leao et al., 2010). HRMS m/z 1524.7673 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C45H59N7O9Na, 1524.7602).

4.4. Racemization of D-Homotyrosine

LD-Hty was obtained from D-Hty via an acetylation–deacetylation process (Sealock et al., 1946). D-homotyrosine hydrobromide (100 mg, 0.00036 mol; Chem–Impex International Inc., Wood Dale, USA) and NaOH (46.6 mg, 0,00115 mol) were dissolved in H2O (1.12 mL), and Ac2O (600 μL, Sigma–Aldrich Inc., Louis, USA) was added in ten portions at 3 min intervals with continuous stirring. The reaction mixture was stirred at 65 °C for 6 h, and then evaporated in vacuo to give a thick syrup (132 mg), which was extracted by acetone and concentrated in vacuo to afford crude diacetylated LD-homotyrosine (99 mg) as yellow oil, confirmed by IT–TOF MS: HRMS m/z 302.1004 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C14H17NO5Na, 302.1004). The crude diacetylated LD-homotyrosine was dissolved in 2 N NaOH (400 μL), and stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The resulting solution was neutralized to pH 7 by 6 N HCl and evaporated in vacuo to give a thick syrup which was extracted by acetone and concentrated in vacuo to afford crude N-acetylated LD-homotyrosine (78 mg) as yellow oil, confirmed by IT–TOF MS: HRMS m/z 260.0898 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C12H15NO4Na, 260.0899). The residue was hydrolyzed with 6 N HCl (2 mL) in a sealed thick glass tube at 102 °C for 3.5 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give crude LD-homotyrosine (70.1 mg) as a red solid, [α]D ≈ 0, confirmed by IT–TOF MS. LD-Homotyrosine: HRMS m/z 196.0968 [M + H]+ (calcd for C10H14NO3, 196.0895).

4.5. Acid hydrolysis of 1 and 2, and Marfey’s analyses of the hydrolyzates

In separate reactions, compounds 1 (0.2 mg) or 2 (0.2 mg) were dissolved in 6 N HCl (0.4 ml), and heated at 110 °C in a sealed vial for 13 h. The cooled reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The amino acid mixture was resuspended in H2O (40 μL). A solution of 1% (1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl)-5-L-alanine amide (FDAA) in acetone (100 μL) and 1 M NaHCO3 (100 μL) was added to each reaction vessel. The reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 2 h and the resulting solution was neutralized using 2 M HCl. The FDAA-amino acid derivatives, from hydrolyzates, were compared with similarly derivatized standard amino acids by HPLC analysis at 340 nm. The column (Alltima RP-C8, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm) was eluted with a linear gradient of (A) CH3CN containing 0.65% AcOH and (B) H2O containing 0.65% AcOH from 20% to 42% (A) over 70 min followed by another gradient elution from 42% to 45% (A) over 20 min at flow rate: 0.5 mL/min. The standards gave the following retention times in min: 48.2 for FDAA; 67.5 for L-Ile, 76.4 for D-Ile; 66.8 for L-allo-Ile, 75.9 for D-allo-Ile; 69.5 for L-Phe, 76.1 for D-Phe; 71.1 for L-Lys, 73.4 for D-Lys; 77.8 for L-Hph, 85.8 for D-Hph; 58.0 for L-Hty, 63.2 for D-Hty; 42.1 for L-N-MeAla, 47.2 for D-N-MeAla.

4.6. 20S Proteasome Assay

The proteasome assay was performed according to the protocol provided with the BIOMOL 20S Proteasome Assay Kit for Drug Discovery (BIOMOL International LP, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA catalog number AK740-0001). The protocol was modified such that the 10 min incubation period was performed at 37 °C. Enzyme was acquired from BostonBiochem (20S proteasome, human, BostonBiochem, USA) and substrate from BIOMOL (Suc-LLVY-AMC). This substrate is specific for the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome. Fluorescence was measured using either a Tecan Genios Pro microplate reader or a Hewlett Packard model AF10000 fluorimeter with an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm. The positive control was bortezomib (IC50 2.5 nM).

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Structure of lyngbyaureidamide A (1) and B (2), lyngbyazothrins C (3) and D (4)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant P01CA125066. We thank Dr. A. Krunic for performing the DEPTQ experiment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beresovsky D, Hadas O, Livne A, Sukenik A, Kaplan A, Carmeli S. Toxins and biologically active secondary metabolites of Microcystis sp. isolated from Lake Kinneret. Isr J Chem. 2006;46:79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii K, Sivonen K, Adachi K, Noguchi K, Sano H, Hirayama K, Suzuki M, Harada K. Comparative study of toxic and non-toxic cyanobacterial products: novel peptides from toxic Nodularia spumigena AV1. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5525–5528. [Google Scholar]

- Gesner-Apter S, Carmeli S. Protease inhibitors from a water bloom of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1429–1436. doi: 10.1021/np900340t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grach-Pogrebinsky O, Carmeli S. Three novel anabaenopeptins from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10233–10238. [Google Scholar]

- Harada K, Fujii K, Shimada T, Suzuki M, Sano H, Adachi K, Carmichael WW. Two cyclic peptides, anabaenopeptides, a third group of bioactive compounds from the cyanobacterium Anabaena flos-aquae NRC 525-17. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:1511–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Itou Y, Suzuki S, Ishida K, Murakami M. Anabaenopeptins G and H, potent carboxypeptidase A inhibitors from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii (NIES-595) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1243–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal P, Singh PK, Prasanna R. Cyanobacterial bioactive molecules – an overview of their toxic properties. Can J Microbiol. 2008;54:701–717. doi: 10.1139/w08-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi J, Sato M, Ishibashi M, Shigemori H, Nakamura T, Ohizumi Y. Keramamide A, a novel peptide from the Okinawan marine sponge Theonella sp. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1991a;1:2609–2611. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi J, Sato M, Murayama T, Ishibashi M, Wälchi MR, Kanai M, Shoji J, Ohizumi Y. Konbamide, a novel peptide with calmodulin antagonistic activity from the Okinawan marine sponge Theonella Sp. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1991b:1050–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Leão PN, Pereira AR, Liuc WT, Ngd J, Pevznere PA, Dorrestein PC, König GM, Vasconcelosa MTSD, Vasconcelosa VM, Gerwick WH. Synergistic allelochemicals from a freshwater cyanobacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:11183–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914343107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luesch H, Pangilinan R, Yoshida WY, Moore RE, Paul VJ. Pitipeptolides A and B, new cyclodepsipeptides from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscule. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:304–307. doi: 10.1021/np000456u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfey P. Determination of D-amino acids. II. Use of a bifunctional reagent, 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1984;49:591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew S, Ross C, Paul VJ, Luesch H. Pompanopeptins A and B, new cyclic peptides from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya confervoides. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:4081–4089. [Google Scholar]

- Mian P, Heilmann J, Bürgi HR, Sticher O. Biological screening of terrestrial and freshwater cyanobacteria for antimicrobial activity, brine shrimp lethality, and cytotoxicity. Pharm Biol. 2003;41:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Suzuki S, Itou Y, Kodani S, Ishida K. New Anabaenopeptins, potent carboxypeptidase-A inhibitors from the cyanobacterium Aphanizomenon flos-aquae. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1280–1282. doi: 10.1021/np000120k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müeller D, Krick A, Kehraus S, Mehner C, Hart M, Küpper FC, Saxena K, Prinz H, Schwalbe H, Janning P, Waldmann H, König GM. Brunsvicamides A-C: sponge-related cyanobacterial peptides with mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitory activity. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4871–4878. doi: 10.1021/jm060327w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura HS, Philmus B, Portmann C, Hemscheidt TK. Homotyrosine-containing cyanopeptolins 880 and 960 and anabaenopeptins 908 and 915 from Planktothrix agardhii CYA 126/8. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:172–176. doi: 10.1021/np800557m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza A, Keffer JL, Lloyd JR, Colin PL, Bewley CA. Paltolides A-C, anabaenopeptin-type peptides from the Palau sponge Theonella swinhoei. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:485–488. doi: 10.1021/np900728x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshef V, Carmeli S. Schizopeptin 791, a new anabeanopeptin-like cyclic peptide from the cyanobacterium Schizothrix sp. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:1187–1189. doi: 10.1021/np020039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SJ, Tenney K, Yee DF, Martinez L, Media JE, Valeriote FA, van Soest RWM, Crews P. Probing the bioactive constituents from chemotypes of the sponge Psammocinia aff. bulbosa. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1002–1009. doi: 10.1021/np070171i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T, Kaya K. Oscillamide Y, a chymotrypsin inhibitor from toxic Oscillatoria agardhlii. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5933–5936. [Google Scholar]

- Sano T, Usui T, Ueda K, Osada H, Kaya K. Isolation of new protein phosphates inhibitors from two cyanobacteria species, Planktothrix spp. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:1052–1055. doi: 10.1021/np0005356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EW, Harper MK, Faulkner DJ. Mozamides A and B, cyclic peptides from a Theonellid sponge from Mozambique. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:779–782. [Google Scholar]

- Sealock RR. Preparation of d-tyrosine, its acetyl derivatives, and d-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine. J Biol Chem. 1946;166:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kate BN, Banerjee UC. Bioactive compounds from cyanobacteria and microalgae: an overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2005;25:73–95. doi: 10.1080/07388550500248498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HJ, Matsuda H, Murakami M, Yamaguchi K. Anabaenopeptins E and F, two new cyclic peptides from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii (NIES-204) J Nat Prod. 1997;60:139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tan TL. Bioactive natural products from marine cyanobacteria for drug discovery. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:954–979. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemoto H, Yahiro Y, Shigemori H, Tsuda M, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Kobayashi J. Keramamides K and L, new cyclic peptides containing unusual tryptophan residue from Theonella sponge. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:6719–6724. [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner RMV, Drummond AK, Wright JLC. Biogenetic diversity of cyanobacterial metabolites. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2007:6189–6217. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(06)61004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker M, von Dohren H. Cyanobacterial peptides - Nature’s own combinatorial biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:530–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, Craig M, Holmes CFB, Andersen RJ. Ferintoic acids A and B, new cyclic hexapeptides from the freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:570–575. [Google Scholar]

- Zafrir-Ilan E, Carmeli S. Eight novel serine proteases inhibitors from a water bloom of the cyanobacterium Microcystis sp. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9194–9202. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin EN, Jansen R, Nimtz M, Wray V, Preisitsch M, Lalk M, Mundt S. Lyngbyazothrins A-D antimicrobial cyclic undecapeptides from the cultured cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1373–1378. doi: 10.1021/np8007792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.