Abstract

Objectives

Despite the promise of expanded health insurance coverage for children in the United States, a usual source of care (USC) may have a bigger impact on a child’s receipt of preventive health counseling. We examined the effects of insurance versus USC on receipt of education and counseling regarding prevention of childhood injuries and disease.

Methods

We conducted secondary analyses of 2002-2006 data from a nationally-representative sample of child participants (≤17 years) in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (n=49,947). Results. Children with both insurance and a USC had the lowest rates of missed counseling, and children with neither one had the highest rates. Children with only insurance were more likely than those with only a USC to have never received preventive health counseling from a health care provider regarding healthy eating (aRR 1.21, 95% CI 1.12-1.31); regular exercise (aRR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01-1.12), use of car safety devices (aRR 1.10, 95% CI 1.03-1.17), use of bicycle helmets (aRR 1.11, 95% CI 1.05-1.18), and risks of second hand smoke exposure (aRR 1.12, 95% CI 1.04-1.20).

Conclusions

A USC may play an equally or more important role than insurance in improving access to health education and counseling for children. To better meet preventive counseling needs of children, a robust primary care workforce and improved delivery of care in medical homes must accompany expansions in insurance coverage.

Keywords: child health, child preventive health, health insurance, usual source of care, access to health care, health care disparities, health policy, health care reform

INTRODUCTION

Receipt of preventive services in childhood is an important investment in long term health.1 Yet, few children in the United States receive all recommended care, and even among insured children, there are significant disparities.2 Insurance coverage is necessary to access care, but may not be sufficient,3, 4 especially if individuals have no place to obtain care.5 Recent estimates report that nearly 10% of children are without a usual source of care (USC). The percent without a USC is much higher among uninsured children.6, 7 The emphasis on health insurance expansions in the United States Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 begs the question: if the United States achieves (near) universal insurance coverage for children, will it matter whether each child has a USC? In the case of education and counseling, a USC might be equally or more important than health insurance in facilitating receipt of preventive health counseling regarding prevention of childhood injuries and disease. We aimed to test the hypothesis that having a USC may have a stronger association with a child’s receipt of preventive health counseling than health insurance coverage.

The study of how health insurance or how a USC might affect access to health care services is not new,8 and having health insurance is strongly linked with also having a USC. Children with one are more likely to have the other; however, not all children with health insurance have a USC and vice versa. Because of the known associations between health insurance and having a USC, past investigations of the individual effect of either health insurance or a USC on access to care have often controlled for the other factor; however, few studies have directly compared these two predictors, and none have assessed national data regarding receipt of preventive counseling.9,10 The primary objective of this study was to ascertain the effect of having both health insurance and a USC, health insurance versus a USC, or neither one on parental reports of preventive health counseling received by children in the United States.

METHODS

Data

We analyzed data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component (MEPS-HC), which produces estimates for the civilian, non-institutionalized United States population.11, 12 MEPS-HC respondents are interviewed 5 times over a 2-year period, with an overlapping panel design that facilitates the combination of data from two overlapping panels for each year. We combined data from 2002 through 2006 because these five years have a common variance structure necessary to ensure compatibility and comparability of our variables within the complex sample design.13 We included children ≤17 years of age with positive full-year weights and known full-year insurance/USC status (n=49,947), representative of nearly 73 million children. In multivariate analyses, we excluded the 1,731 children who could not be linked to at least one biological, adopted, and/or step parent residing in the household (we could not link foster parents or non-parent guardians).

Variables and Analyses

Preventive Health Care Counseling/Anticipatory Guidance Variables

We included five outcomes related to whether or not parent / child ever received anticipatory guidance from a health care provider regarding (1) healthy eating, (2) regular exercise, (3) seat belts/safety car seats, (4) bicycle/tricycle helmets, and (5) risks of second-hand smoke exposure. The first four questions were asked only of children aged 2-17 (excluding the 4,934 MEPS-HC children <2 years).

Health Insurance and Usual Source of Care (USC) Variables

The importance of full-year health insurance for children is well-established;14-16 thus, we created two insurance groups: insured all year, not insured all year. We assessed whether each child had a USC, based on response to the question: “Is there a particular doctor’s office, clinic, health center, or other place that you usually goes if (CHILD’s NAME) is sick or if you need advice about (CHILD’s NAME)’s health?” We then created four primary predictor subgroups, including: (1) insured all year and had a USC (Yes INS/Yes USC, n=36,177); (2) insured all year but no USC (Yes INS/No USC, n=2,881); (3) not insured all year but had a USC (No INS/Yes USC, n=7,808); (4) not insured all year and no USC (No INS/No USC, n=3,081).

We used the conceptual model designed by Aday and Andersen17 to guide the identification of ten covariates that might influence children’s access to preventive health counseling. In 2-tailed, chi-square analyses, each covariate was significantly associated with at least one outcome (p<0.10); thus, all ten were included in multivariate logistic regression models.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square analyses to ascertain associations between the four INS/USC subgroups and the ten socio-demographic covariables. Second, we stratified the population by health insurance status and conducted univariate and multivariate analyses to assess socio-demographic characteristics associated with having no USC. We also descriptively assessed the type of USC among the subgroup of children with a USC. Third, we used chi-square analyses to ascertain associations between the four INS/USC subgroups and, respectively, the five preventive health counseling outcomes. Then, we used a series of logistic regression models to assess the adjusted associations between the INS/USC groups and the outcomes, and to calculate predicted probabilities of outcomes by INS/USC groups. In these models, we were able to achieve direct comparisons between the effects of having only insurance versus having only a USC on receipt of anticipatory guidance by systematically assigning each of the four INS/USC groups as the reference group. We report measures of association as risk ratios because odds ratios do not accurately approximate the risk ratio for common outcomes.18

We used SUDAAN Version 10.0.1 for all statistical analyses to account for the complex sampling design of the MEPS. All statistically significant results were significant at p<.05. This study protocol was reviewed by the Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt because data are publicly available.

RESULTS

Over three-quarters of children had both a USC and full-year insurance (76.8%), 5.0% had only a USC, 14.0% had only insurance, and 4.2% had neither one. Children with insurance alone were more likely to be older, non-white/non-Hispanic, from lower earning households, or living with a single parent. Children with a USC alone were more likely to be Hispanic and have parents not insured all year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of US Children, By Health Insurance Status and/or a Usual Source of Care (2002-2006)

| Demographic Variables | Yes INS1 Yes USC (Weighted %) | Yes INS2 No USC (Weighted %) | No INS3 Yes USC (Weighted %) | No INS4 No USC (Weighted %) | Total Child Population (Weighted %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population (row percentage = 100%) | 36,177 (76.8%) | 2,881 (5.0%) | 7,808 (14.0%) | 3,081 (4.2%) | 49,947 (100%) |

|

| |||||

| Child’s Age(years) (N=49,947) * | |||||

| 0-4 | 27.8 | 15.9 | 28.5 | 15.8 | 26.8 |

| 5-9 | 27.8 | 22.5 | 26.8 | 24.8 | 27.3 |

| 10-13 | 22.3 | 25.0 | 22.9 | 24.9 | 22.6 |

| 14-17 | 22.0 | 36.6 | 21.9 | 34.5 | 23.3 |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity (N=49,947) * | |||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 16.2 | 22.9 | 27.5 | 46.5 | 19.4 |

| White Not Hispanic | 62.1 | 46.1 | 52.2 | 31.8 | 58.7 |

| Non-White, Non-Hispanic | 21.7 | 31.0 | 20.3 | 21.7 | 22.0 |

|

| |||||

| Parental Employment (N=48,183) *§ | |||||

| Employed | 91.8 | 86.8 | 88.3 | 84.5 | 90.8 |

| Not Employed | 8.2 | 13.2 | 11.7 | 15.5 | 9.2 |

|

| |||||

| Geographic Residence (N=49,902) * | |||||

| Northeast | 19.5 | 8.4 | 14.0 | 5.9 | 17.6 |

| Midwest | 23.4 | 16.7 | 19.0 | 13.9 | 22.1 |

| South | 34.2 | 46.2 | 40.8 | 45.0 | 36.1 |

| West | 22.9 | 28.7 | 26.3 | 35.1 | 24.2 |

|

| |||||

| Parental Education (N=48,116) *§ | |||||

| At least 12 years | 88.3 | 79.8 | 80.2 | 63.0 | 85.7 |

| Less than 12 years | 11.7 | 20.2 | 19.8 | 37.1 | 14.3 |

|

| |||||

| Household Income as a percent of Federal Poverty Level (FPL) (N=49,947) * | |||||

| Poor (<100%FPL) | 16.3 | 22.5 | 20.7 | 29.2 | 17.7 |

| Near Poor (100 to <125%FPL) | 4.7 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 5.4 |

| Low Income (125 to <200% FPL) | 14.2 | 16.2 | 22.1 | 26.2 | 15.9 |

| Middle Income (200 to <400% FPL) | 33.3 | 33.7 | 32.4 | 27.1 | 32.9 |

| High Income (≥400% FPL) | 31.6 | 20.9 | 17.0 | 7.7 | 28.0 |

|

| |||||

| Family Composition$ (N=49,947) * | |||||

| Linked with 2 parents in the household | 73.8 | 63.2 | 66.6 | 60.4 | 71.7 |

| Linked with 1 parent in the household | 23.9 | 31.9 | 30.2 | 32.8 | 25.5 |

| No linked parents in the household | 2.3 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 2.7 |

|

| |||||

| Child’s Health Status (N=49,944) * | |||||

| Excellent | 52.9 | 52.5 | 49.8 | 44.5 | 52.1 |

| Not Excellent | 47.2 | 47.5 | 50.2 | 55.5 | 47.9 |

|

| |||||

| Parent’s Health Insurance Status (N=48,216) *§ | |||||

| Insured all year (at least 1) | 86.9 | 79.0 | 31.0 | 19.0 | 76.0 |

| Not insured all year | 13.1 | 21.0 | 69.0 | 81.0 | 24.0 |

|

| |||||

| Parent’s Usual Source of Care (N=48,135) *§ | |||||

| Yes USC (at least 1) | 88.0 | 32.7 | 79.8 | 22.4 | 81.5 |

| No USC | 12.0 | 67.3 | 20.2 | 77.6 | 18.5 |

Note: Column percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding (rounded to nearest tenth).

Total in sample with known usual source of care and insurance status information = 49,947 (weighted N=72.9 million).

Yes Usual Source of Care/Yes Insurance All Year

No Usual Source of Care/Yes Insurance All Year

Yes Usual Source of Care/No Insurance All Year

No Usual Source of Care/No Insurance All Year

p<0.01 in the χ2 analysis for overall differences between subcategories of each demographic characteristic.

Children in the MEPS-HC can only be linked to biological, adopted, and/or step parents residing in the same household (MEPS does not include variables for linking foster parents or non-parent guardians in this way).

Children with no parent record(s) linked (n=1,731) were excluded from comparisons examining parental employment, education, insurance status, and usual source of care.

A much higher percentage of uninsured children had no USC, when compared with insured children. In most cases, socio-demographic characteristics associated with higher odds of having no USC were similar among insured versus uninsured children; however, there were some differences (see Table 2). Among insured children, parental educational attainment was not significantly associated with higher odds of having no USC while it was a significant factor for uninsured children. Child’s health status of excellent and having parents without insurance were significantly associated with lower odds of having no USC among insured children, but not a significant factor for uninsured children. Having at least one parent with a USC was the predictor most highly associated with greater likelihood of a child having a USC, among both insured and uninsured children.

Table 2.

Associations between Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Having No Usual Source of Care (USC), Among Children with Insurance and Without Insurance (2002-2006)

| Child insured all year (N=36,177) | Child not insured all year (N=2,881) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No USC | No USC | No USC | No USC | |

| Demographic Variables | Weighted % | aRR (95% CI) | Weighted % | aRR (95% CI) |

| Child’s Age (years) | ||||

| 0-4 | 3.6 | 1.00 | 14.3 | 1.00 |

| 5-9 | 5.0 | 1.67 (1.43-1.94) | 21.8 | 1.44 (1.24-1.69) |

| 10-13 | 6.8 | 2.45 (2.08-2.87) | 24.7 | 1.72 (1.47-2.00) |

| 14-17 | 9.7 | 3.80 (3.25-4.45) | 32.2 | 2.27 (1.95-2.65) |

|

| ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 8.4 | 1.24 (1.03-1.51) | 33.7 | 1.28 (1.05-1.55) |

| White Not Hispanic | 4.6 | 1.00 | 15.5 | 1.00 |

| Non-White, Non-Hispanic | 8.5 | 1.41 (1.16-1.71) | 24.4 | 1.30 (1.10-1.53) |

|

| ||||

| Parental Employment | ||||

| Employed | 5.6 | 1.00 | 21.7 | 1.00 |

| Not Employed | 9.2 | 1.37 (1.14-1.65) | 27.7 | 1.15 (1.01-1.30) |

|

| ||||

| Geographic Residence | ||||

| Northeast | 2.7 | 1.00 | 11.3 | 1.00 |

| Midwest | 4.4 | 1.41 (1.04-1.92) | 18.0 | 1.45 (1.09-1.92) |

| South | 8.0 | 1.85 (1.39-2.47) | 24.9 | 1.35 (1.06-1.73) |

| West | 7.5 | 1.85 (1.38-2.48) | 28.6 | 1.59 (1.22-2.07) |

|

| ||||

| Parental Education | ||||

| At least 12 years | 5.4 | 1.00 | 18.5 | 1.00 |

| Less than 12 years | 9.8 | 1.17 (0.98-1.38) | 35.0 | 1.27 (1.12-1.44) |

|

| ||||

| Household Income as a percent of Federal Poverty Level (FPL) | ||||

| Poor (<100%FPL) | 8.2 | 1.09 (0.88-1.35) | 29.9 | 1.25 (1.02-1.53) |

| Near Poor (100 to <125%FPL) | 8.4 | 1.33 (1.04-1.70) | 27.5 | 1.28 (1.00-1.64) |

| Low Income (125 to <200% FPL) | 6.9 | 1.18 (0.96-1.45) | 26.3 | 1.34 (1.09-1.64) |

| Middle Income (200 to <400% FPL) | 6.2 | 1.24 (1.05-1.48) | 20.1 | 1.21 (1.00-1.48) |

| High Income (≥400% FPL) | 4.1 | 1.00 | 12.0 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| Family Composition | ||||

| Linked with 2 parents in the household | 5.3 | 1.00 | 21.5 | 1.00 |

| Linked with 1 parent in the household | 8.0 | 0.81 (0.70-0.95) | 24.7 | 0.88 (0.78-0.99) |

| No linked parents in the household | 12.2 | N/A | 38.9 | N/A |

|

| ||||

| Child’s Health Status | ||||

| Excellent | 6.0 | 1.00 | 21.2 | 1.00 |

| Not Excellent | 6.1 | 0.86 (0.78-0.96) | 25.0 | 1.05 (0.95-1.17) |

|

| ||||

| Parent’s Health Insurance Status | ||||

| Insured all year (at least 1 parent) | 5.4 | 1.00 | 15.1 | 1.00 |

| Not insured all year | 9.2 | 0.66 (0.57-0.78) | 25.4 | 1.03 (0.91-1.17) |

|

| ||||

| Parent’s Usual Source of Care | ||||

| Yes USC (at least 1 parent) | 2.3 | 1.00 | 7.5 | 1.00 |

| No USC | 26.1 | 12.21 (10.48-14.23) | 52.7 | 6.24 (5.33-7.30) |

Source: 2002-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Household Component

aRR: adjusted risk ratio, CI: confidence interval

Note: Children with no parent record(s) linked (n=1,731) were excluded from the logistic regression because information could not be obtained for parental employment, education, insurance status, and usual source of care.

Among the subgroup of children with a USC, as shown in Table 3, 59.6% reported a facility as their USC, 25.2% reported a specific person, and 15.2% reported a person in a facility. Less than 1% of respondents with a facility, or person-in-facility, type of USC reported a hospital emergency room as their USC.

Table 3.

Type of Usual Source of Care for Those Children with a USC (2002-2006)

| Total (N=43,985) | |

|---|---|

| Type of Usual Source of Care* | Weighted % |

|

| |

| Facility | 59.6 |

| Person | 25.2 |

| Person-In-Facility | 15.2 |

|

| |

| Among Those Reporting Type of USC as a Facility* | N=26,496 |

|

| |

| Type of facility: | |

| Hospital Clinic/Outpatient Department | 21.1 |

| Hospital Emergency Room | 0.5 |

| Non-Hospital Place | 78.4 |

|

| |

| Particular Provider: | |

| Has a Particular Provider within this Facility | 67.9 |

| Does Not Have a Particular Provider within this Facility | 32.1 |

|

| |

| Among Those Reporting Type of USC as a Person* | N=11,396 |

|

| |

| Type of provider: | |

| General/Family Practice | 33.3 |

| Pediatrician | 62.8 |

| Other (e.g. another MD specialty, NP, PA, ND) | 3.8 |

|

| |

| Among Those Reporting Type of USC as a Person Within a Facility* | N=6,093 |

|

| |

| Type of facility: | |

| Hospital Clinic/Outpatient Department | 16.6 |

| Hospital Emergency Room | ** |

| Non-Hospital Place | 83.1 |

|

| |

| Type of provider: | |

| General/Family Practice | 31.6 |

| Pediatrician | 65.0 |

| Other Type of Provider (e.g. another MD specialty, NP, PA, ND) | 3.5 |

Source: 2002-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Household Component

For all persons who reported having a USC, MEPS interviewers asked respondents to give the name of the medical person, doctor’s office, clinic, health center, or other place that the person usually goes if he/she is sick or needs advice about his/her health. AHRQ staff then coded these responses into a “type of USC” variable with categories of facility, person, or a person in a facility (Person-in-Facility). Then, depending on the respondents’ answers, subsequent questions were asked to elicit more detail about the type of USC.

Value represented by fewer than 30 people; estimate may not be reliable.

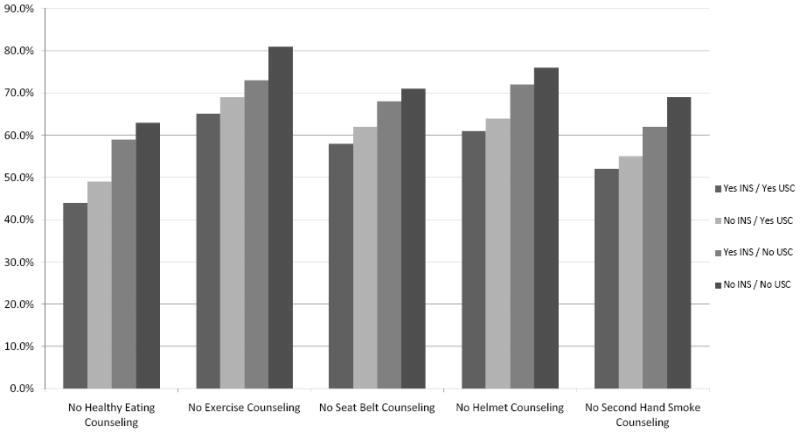

Preventive health counseling was estimated to be received by less than half of all children, after adjusting for covariates. A USC alone was associated with lower rates of having never received preventive health counseling than insurance alone, on each of 5 measures, see Figure 1.”

Figure 1. Estimated Percentages* of US Children Reporting Never Receiving Preventive Health Counseling.

*Estimated percentages are adjusted for child’s age, child’s race/ethnicity, parental employment, region of residence, parental education, household income, family composition, child’s health status, parent’s health insurance status, and parent’s usual source of care status.

No Healthy Eating Counseling = Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding child’s eating healthy (n=42,781, children aged 2-17).

No Exercise Counseling = Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding amount and kind of exercise, sports or physically active hobbies child should have (n=42,744, children aged 2-17).

No Seat Belt Counseling = Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about using a safety seat, booster seat, or lap and shoulder belts when child rides in the car (n=42,727, children aged 2-17).

No Helmet Counseling = Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about the child’s using a helmet when riding a bicycle or motorcycle (n=42,698, children aged 2-17).

No Second Hand Smoke Counseling = Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider that smoking in the house can be bad for the child’s health (n=47,566, children aged 0-17).

Note: Each multivariable model has a slightly different N, due to missing responses on outcomes and covariates.

Table 4 shows similar patterns, displayed as adjusted risk ratios. Again, in all cases, the group of uninsured children without a USC (No INS/No USC) had the highest likelihood of never having received preventive health counseling, as compared with the group of insured children with a USC (Yes INS/Yes USC) who had the lowest.

Table 4.

Multivariate Associations Between US Child and Family Characteristics and Children’s Receipt of Preventive Counseling/Anticipatory Guidance (2002-2006)

| Demographic and Other Characteristics | Never had Counseling regarding Healthy Eatinga | Never had Counseling regarding Exercise b | No Counseling regarding Use of Safety Restraints in carsc | Never had Counseling regarding use of Bike Helmetsd | No Counseling regarding Smoking in House Being Bad for Child’s Healthe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) | |

| Child Health INS/USC (ref Yes INS/Yes USC1) | |||||

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 1.34 (1.26-1.43) | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | 1.16 (1.10-1.23) | 1.18 (1.12-1.25) | 1.18 (1.11-1.26) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) | 1.06 (1.02-1.11) | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) |

| No INS/No USC4 | 1.43 (1.35-1.51) | 1.24 (1.20-1.29) | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | 1.25 (1.19-1.31) | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) |

|

| |||||

| Child’s Age (years) * (ref ≤4) | |||||

| 5-9 | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) | 0.89 (0.87-0.92) | 1.41 (1.36-1.47) | 0.82 (0.80-0.85) | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) |

| 10-13 | 1.22 (1.17-1.28) | 0.85 (0.83-0.88) | 1.59 (1.53-1.66) | 0.90 (0.87-0.94) | 1.25 (1.20-1.30) |

| 14-17 | 1.33 (1.27-1.40) | 0.88 (0.85-0.91) | 1.67 (1.59-1.75) | 1.05 (1.02-1.09) | 1.29 (1.24-1.34) |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity (ref White Not Hispanic) | |||||

| Hispanic, Any Race | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) | 0.89 (0.85-0.92) | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) | 0.99 (0.95-1.03) | 0.97 (0.92-1.02) |

| Non-White, Non-Hispanic | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) |

|

| |||||

| Parental Employment (ref Employed) | |||||

| Not Employed | 0.96 (0.90-1.02) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | 0.97 (0.92-1.03) | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) |

|

| |||||

| Geographic Residence (ref Northeast) | |||||

| Midwest | 1.23 (1.12-1.36) | 1.17 (1.10-1.25) | 1.13 (1.04-1.22) | 1.18 (1.10-1.27) | 1.01 (0.95-1.08) |

| South | 1.20 (1.09-1.31) | 1.16 (1.10-1.22) | 1.16 (1.07-1.24) | 1.26 (1.18-1.34) | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) |

| West | 1.24 (1.13-1.36) | 1.13 (1.06-1.20) | 1.12 (1.04-1.20) | 1.16 (1.08-1.25) | 1.05 (0.98-1.12) |

|

| |||||

| Parental Education (ref At least 12 years) | |||||

| Less than 12 years | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 1.06 (1.03-1.09) | 1.01 (0.97-1.05) | 1.04 (1.00-1.09) | 0.90 (0.86-0.95) |

|

| |||||

| Household Income as a percent of Federal Poverty Level (FPL) (ref High Income) | |||||

| Middle Income | 1.20 (1.13-1.26) | 1.11 (1.07-1.15) | 1.06 (1.01-1.10) | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 0.91 (0.88-0.95) |

| Low Income | 1.25 (1.17-1.34) | 1.11 (1.06-1.15) | 1.10 (1.05-1.15) | 1.11 (1.06-1.17) | 0.85 (0.81-0.89) |

| Near Poor | 1.29 (1.19-1.41) | 1.12 (1.05-1.18) | 1.06 (1.00-1.13) | 1.11 (1.04-1.18) | 0.80 (0.74-0.87) |

| Poor | 1.21 (1.14-1.29) | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) | 1.05 (0.99-1.10) | 1.09 (1.03-1.15) | 0.76 (0.72-0.81) |

|

| |||||

| Family Composition (ref Linked with 2 parents in the household) | |||||

| Linked with 1 parent in the household | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 1.02 (1.00-1.05) | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) |

|

| |||||

| Child’s Health Status (ref Excellent) | |||||

| Not Excellent | 0.92 (0.89-0.95) | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | 1.02 (0.99-1.04) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 0.94 (0.91-0.96) |

|

| |||||

| Parent’s Health Insurance Status (at least 1 parent insured all year) | |||||

| No Parent Insured all year | 1.01 (0.97-1.06) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 1.05 (1.01-1.08) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

|

| |||||

| Parent USC (ref at least one parent has a USC) | |||||

| No Parent USC | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) |

Source: 2002-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Household Component

aRR: adjusted risk ratio, CI: confidence interval

Note: Children with no parent record(s) linked (n=1,731) were excluded from all models because information could not be obtained for parental employment, education, insurance status, and usual source of care.

For the receipt of preventive counseling services outcomes, except second hand smoke exposure, the lowest age category includes only children ages 2-4, rather than 0-4, because these questions were only asked of children ages 2-17.

Yes Insurance All Year/Yes Usual Source of Care

Yes Insurance All Year/No Usual Source of Care

No Insurance (uninsured or partial coverage)/Yes Usual Source of Care

No Insurance (uninsured or partial coverage)/No Usual Source of Care

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding child’s eating healthy.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding amount and kind of exercise, sports or physically active hobbies child should have.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about using a safety seat, booster seat, or lap and shoulder belts when child rides in the car.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about the child’s using a helmet when riding a bicycle or motorcycle.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider that smoking in the house can be bad for the child’s health.

In head-to-head comparisons between the two middle subgroups (Table 5, columns 1 and 2), children with insurance alone (Yes INS/No USC) were significantly more likely than those with only a USC (No INS/Yes USC as reference group) to report all five unmet preventive health counseling outcomes.

Table 5.

Adjusted Risk Ratios of US Children Having Never Received Anticipatory Guidance, using each Subgroup of Insurance/Usual Source of Care as the Reference Group

| COLUMN 1 Yes INS/No USC2 As reference group aRR* (95% CI) |

COLUMN 2 No INS/Yes USC3 As reference group aRR* (95% CI) |

COLUMN 3 No INS/No USC4 As reference group aRR* (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Preventive Counseling / Anticipatory Guidance | |||

|

| |||

| No Counseling regarding Healthy Eatinga | |||

| Child Health INS/USC | |||

| Yes INS/Yes USC1 | 0.75 (0.70-0.79) | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) | 0.70 (0.66-0.74) |

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 1.00 | 1.21 (1.12-1.31) | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 0.83 (0.76-0.90) | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.72-0.83) |

| No INS/No USC4 | 1.07 (0.99-1.15) | 1.29 (1.20-1.38) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| No Counseling regarding Exerciseb | |||

| Child Health INS/USC | |||

| Yes INS/Yes USC1 | 0.88 (0.84-0.93) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) | 0.80 (0.77-0.84) |

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 1.00 | 1.06 (1.01-1.12) | 0.91 (0.86-0.96) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.82-0.89) |

| No INS/No USC4 | 1.10 (1.04-1.16) | 1.17 (1.12-1.22) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| No Counseling regarding Use of Seat belts/Safety Seats in carsc | |||

| Child Health INS/USC | |||

| Yes INS/Yes USC1 | 0.86 (0.81-0.91) | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.82 (0.78-0.86) |

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 1.00 | 1.10 (1.03-1.17) | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 0.91 (0.86-0.97) | 1.00 | 0.86 (0.82-0.91) |

| No INS/No USC4 | 1.06 (0.99-1.12) | 1.16 (1.10-1.22) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| No Counseling regarding use of Bike Helmetsd | |||

| Child Health INS/USC | |||

| Yes INS/Yes USC1 | 0.84 (0.80-0.89) | 0.94 (0.90-0.98) | 0.80 (0.77-0.84) |

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 1.00 | 1.11 (1.05-1.18) | 0.95 (0.89-1.01) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 0.90 (0.85-0.95) | 1.00 | 0.85 (0.81-0.90) |

| No INS/No USC4 | 1.06 (0.99-1.12) | 1.18 (1.12-1.24) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| No Counseling regarding Smoking in House Being Bad for Child’s Healthe | |||

| Child Health INS/USC | 0.85 (0.79-0.90) | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | 0.76 (0.72-0.80) |

| Yes INS/Yes USC1 | 1.00 | 1.12 (1.04-1.20) | 0.90 (0.83-0.96) |

| Yes INS/No USC2 | 0.90 (0.83-0.96) | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.76-0.85) |

| No INS/Yes USC3 | 1.12 (1.04-1.20) | 1.25 (1.18-1.32) | 1.00 |

| No INS/No USC4 | |||

Source: 2002-2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), Household Component

aRR: adjusted risk ratio, CI: confidence interval

Yes Insurance All Year/Yes Usual Source of Care

Yes Insurance All Year/No Usual Source of Care

No Insurance (uninsured or partial coverage)/Yes Usual Source of Care

No Insurance(uninsured or partial coverage)/No Usual Source of Care

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding child’s eating healthy.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider regarding amount and kind of exercise, sports or physically active hobbies child should have.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about using a safety seat, booster seat, or lap and shoulder belts when child rides in the car.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider about the child’s using a helmet when riding a bicycle or motorcycle.

Respondent reported having never received advice from a doctor or health care provider that smoking in the house can be bad for the child’s health.

Covariates in multivariate analysis: child’s age, child’s race/ethnicity, household income, parental education, parental employment, geographic residence, family composition, child’s perceived health status, parent’s insurance status and whether or not parent has a USC.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that not all children with health insurance have a USC, and vice versa. It also reinforces the importance of having both insurance and a USC to optimize children’s receipt of preventive health counseling. This finding suggests that current proposals to greatly expand eligibility for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) or to mandate individual health insurance coverage for everyone in the United States will not achieve optimal delivery of preventive health counseling without a mechanism to ensure adequate provider capacity.19, 20,21,22 It cannot be assumed that gaining stable health insurance will automatically lead to finding a USC.

Further, this study suggests the need to improve overall children’s health care service delivery, regardless of insurance or USC status.2, 3, 5,2, 23 Notably, 64.5% of children with both insurance and a USC did not receive counseling regarding regular exercise. Thus, at a minimum, improving children’s access to preventive health counseling will require expanding health insurance coverage and, at the same time, ensuring the availability of comprehensive and continuous primary care services to all children. Moreover, there is a need to increase the overlap between the inherently synergistic financing and delivery components.5 Recent efforts to build “medical homes” for all children may be moving us in this direction; however, there is still much work to be done.24-32 The simultaneous expansion of medical homes and stable health insurance coverage for children could prove to be the best avenue to improve access and quality. However, if Medicaid and CHIP are expanded within the current delivery environment dominated by fee-for-service provider remuneration, disparate access depending on insurance type will persist and disparity gaps may even widen.33, 34

Limitations

First, secondary data analyses are limited to existing data. Second, the cross-sectional nature of these observations does not support causal inferences. Third, the duration of non-insurance affects the likelihood of having unmet needs.14 However, because the need for health care services cannot be “scheduled” during months of coverage, we chose to consider children to be either insured or not insured all year. Fourth, as with all studies that rely on self-report, response bias remains a possibility. It is possible that those parents who had an established relationship with a provider were more likely to remember or hear the preventive health counseling message. Finally, we recognize that every state (and some cities and counties) have unique insurance programs, and the availability of primary and preventive care services varies widely by region. We included a regional covariate but could not control for local variation.

Conclusions

Expansions in children’s health insurance alone will not ensure finding a USC or receiving preventive counseling. In fact, a USC may have a more important impact than insurance on children’s receipt of preventive health counseling from their health care providers. While the United States expands coverage, policy makers must also create mechanisms to support the expansion of the primary care workforce and to build medical homes in order to adequately meet the needs of newly insured populations. Further, there is a need for additional improvements in the delivery of preventive health counseling to all children, even those fortunate enough to already have both insurance and a USC.

Acknowledgments

This project received direct support from grant numbers K08 HS16181 and R01 HS018569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Oregon Health and Science University Department of Family Medicine. The grant received indirect support from the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), supported by grant number UL1 RR024140 01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Pandhi’s time on this project was supported by grant number K08 AG029527 from the National Institute on Aging. These funding agencies had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. AHRQ collects and manages the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Drs. Julie Hudson and Jessica Vistnes from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality were extremely helpful in guiding our statistical programming. We are grateful to Drs. Eun Sul Lee and Ed Fryer for sharing their biostatistical expertise.

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. DeVoe, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 Sam Jackson Park Rd, mailcode: FM, Portland, OR 97239, Phone 503-494-8936, Fax 503-494-2746, devoej@ohsu.edu.

Carrie J. Tillotson, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239, tillotso@ohsu.edu.

Lorraine S. Wallace, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, 1924 Alcoa Highway, U-67, Knoxville, TN 37920, lwallace@mc.utmck.edu.

Sarah E. Lesko, Center for Researching Health Outcomes, PO Box 1195, Mercer Island, WA 98040, drlesko@centerrho.org.

Nancy Pandhi, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Family Medicine, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 53715, nancy.pandhi@fammed.wisc.edu.

References

- 1.Birken S, Mayer M. An investment in health: anticipating the cost of a usual source of care for children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):77–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007 Oct 11;357(15):1515–1523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeVoe J, Baez A, Angier H, Krois L, Edlund C, Carney P. Insurance + access does not equal health care: typology of barriers to health care access for low-income families. Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5(6):511–518. doi: 10.1370/afm.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selden T, Hudson J. Access to care and utilization among children: estimating the effects of public and private coverage. Medical Care. 2006;44(5 Suppl):I-19–I-26. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000208137.46917.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. Access, primary care, and medical home: rights of passage. Medical Care. 2008;46(10):1015–1016. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fae3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown E. MEPS Statistical Brief #78. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Children’s Usual Source of Care: United States, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoilette L, Clark S, Gebremariam A, et al. Usual source of care and unmet needs among vulnerable children: 1998-2006. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e214–219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gortmaker SL. Medicaid and the health care of children in poverty and near poverty: some successes and failures. Medical Care. 1981;19(6):567–582. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVoe JE, Petering R, Krois L. A usual source of care: supplement or substitute for health insurance among low-income children? Medical Care. 2008 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181866443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allred N, Wooten K, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19- to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S4–S11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [January 10, 2008];MEPS HC-089: 2004 Full Year Consolidated Data File. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h89/h89doc.pdf.

- 12.Cohen J, Monheit A, Beauregard K, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996 Winter;:373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [April 22, 2010];MEPS Pooled Estimation Files. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h36/h36u07doc.shtml.

- 14.DeVoe JE, Graham A, Krois L, Smith J, Fairbrother GL. “Mind the gap” in children’s health insurance coverage: does the length of a child’s coverage gap matter? Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings J, Lavarreda S, Rice T, Brown E. The effects of varying periods of uninsurance on children’s access to health care. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):e411–e418. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane DJ, Zotti ME, Rosenberg D. Factors associated with health care access for Mississippi children with special health care needs. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2005;9(2 Suppl):S23–31. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-3964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research. 1974;9:208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Yu K. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuckerman S, McFeeters J, Cunningham P, Nichols L. Changes in Medicaid physician fees, 1998-2003: implications for physician participation. Health Affairs. 2004;Suppl W4:374–384. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson J. Massachusetts health care reform is a pioneer effort, but complications remain. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(6):489–492. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starfield B. Insurance and the US health care system. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(4):418–419. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long SK, Masi PB. Access and affordability: an update on health reform in Massachusetts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w578–587. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry CD, Kenney GM. Preventive care for children in low-income families: how well do Medicaid and state children’s health insurance programs do? Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):e1393–1401. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starfield B, Shi L. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;2004(113: Suppl):1493–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, Liu JH, Freeman L, Ganz ML. The Pediatric Alliance for Coordinated Care: Evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004 MAY;113(5):1507–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antonelli RC, Antonelli DM. Providing a medical home: The cost of care coordination services in a community-based, general pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004 MAY;113(5):1522–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr MS. The Need to Test the Patient-Centered Medical Home. JAMA. 2008 August 20;300(7):834–835. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A Primary Care Home for Americans: Putting the House in Order. JAMA. 2002 August 21;288(7):889–893. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Will It Stand the Test of Health Reform? JAMA. 2009 May 20;301(19):2038–2040. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romaire MA, Bell JF. The Medical Home, Preventive Care Screenings, and Counseling for Children: Evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Acad Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.010. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen DJ, Bronstein J, Pass MA. Assessing the Extent of Medical Home Coverage Among Medicaid-Enrolled Children. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2002;6(1):59–66. doi: 10.1023/a:1014320301492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens GD, Seid M, Pickering TA, Tsai KY. National disparities in the quality of a medical home for children. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(4):580–589. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang E, Choe M, Meara J, Koempel J. Inequality of access to surgical specialty health care: why children with goverment-funded insurance have less access than those with private insurance in Southern California. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e584–590. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valet R, Kutny D, Hickson G, Cooper W. Family reports of care denials for children enrolled in TennCare. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e37–e42. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]