Abstract

Our objective was to examine mothers’ perspectives of obesity-related health behavior recommendations for themselves and their 0–6 month old infants. A health educator conducted 4 motivational counseling calls with 60 mothers of infants during the first 6 months postpartum. Calls addressed 5 behaviors for infants (breastfeeding, introduction of solid foods, sleep, TV, hunger cues), and 4 for mothers (eating, physical activity, sleep, TV). We recorded detailed notes from each call, capturing responsiveness to recommendations and barriers to change. Two independent coders analyzed the notes to identify themes. Mothers in our study were more interested in focusing on their infants’ health behaviors than on their own. While most were receptive to eliminating their infants’ TV exposure, they resisted limiting TV for themselves. There was some resistance to following infant feeding guidelines, and contrary to advice to avoid nursing or rocking babies to sleep, mothers commonly relied on these techniques. Return to work emerged as a barrier to breastfeeding, yet facilitated healthier eating, increased activity, and reduced TV time for mothers. The early postpartum period is a challenging time for mothers to focus on their own health behaviors, but returning to work appears to offer an opportunity for positive changes in this regard. To improve weight-related infant behaviors, interventions should consider mothers’ perceptions of nutrition and physical activity recommendations and barriers to adherence.

Keywords: Postpartum Women, Infancy, Nutrition, Physical activity, Obesity prevention

Introduction

The postpartum period is a critical window for susceptibility to excess weight gain among women [1, 2], and evidence suggests that a large subset of women have substantial postpartum weight retention [3]. Infancy is also a key period in the development of childhood obesity. Overweight and obesity are prevalent even among the youngest of children, with a nationwide prevalence of 10% among infants 0–23 months old [4], and are associated with obesity later in life [5, 6]. Few studies have examined preventive interventions during the postpartum/infancy period to prevent excess weight gain among mother-infant pairs.

Epidemiologic studies suggest several targets of intervention during the postpartum period to prevent excess weight gain among mothers and their infants, including mother’s diet, physical activity, and sedentary practices [7]; sleep quality and duration in mother [8, 9] and child [10, 11]; and mother-infant feeding interactions [11, 12] and promotion of breastfeeding [11, 13]. In addition, studies have shown in young children an association between television viewing and obesity [14], and television viewing and poor diet quality [14, 15]. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no television viewing for children under 2 years [16]. The success of interventions to target these behaviors and thus reduce excess weight gain during this period of life depends on a woman’s motivation, acceptance, and confidence to work on such behavioral goals [17–19]. Thus, it is important to understand mothers’ barriers and facilitators to recommended behaviors to help inform the development of successful behavior change interventions.

Few qualitative studies have explored in depth the individual needs of postpartum women in achieving health behavior goals for themselves and their infants. A limited number have focused on women’s perceived barriers and facilitators to exercise and healthy eating [20–23] and sleep [24, 25]. Other qualitative studies have examined factors affecting breastfeeding decisions [26–31] and mothers’ perceptions of clinician counseling regarding breastfeeding [32, 33], but there is a paucity of studies that examine mothers’ perceptions of other maternal and infant health behavior recommendations during this life period.

The purpose of this study was to examine mothers’ perspectives of health behavior recommendations to limit obesogenic behaviors in the postpartum period for themselves and their infants. To achieve this goal, we conducted content analysis of summaries of counseling calls with mothers participating in a postpartum intervention to improve obesity-related behaviors such as nutrition, physical activity, and sleep, and to reduce television viewing among mother-infant pairs.

Methods

Study Population

Participants in this study were mothers of infants ages 0–6 months enrolled in a pilot intervention, First Steps for Mommy and Me, a non-randomized controlled trial to improve nutrition and physical activity among mother-infant pairs in the first 6 months of life. Study eligibility criteria included: (1) having an infant age 0–1 month and not born more than 4 weeks premature (2) ability to complete a phone survey in English and (3) no anticipated plans to change the site of pediatric care for the study duration. Infants with serious health conditions that might affect feeding and growth were excluded.

Recruitment and Enrollment

We recruited mother-infant pairs over a 6 month period in 2008 through two primary care pediatric offices of a multi-site group practice in the greater Boston area. Details of recruitment and enrollment for the trial are available elsewhere [8, 34, 35]. In brief, clinic staff at intervention sites identified all newborns entering their practices daily and research staff then mailed study invitation letters to eligible families. We enrolled 60 mother-infant pairs in the intervention group, who formed the sample included in this content analysis. All mothers provided written informed consent at an in-person visit with a research assistant. All study procedures were approved by the human subjects committee of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Motivational Counseling Calls

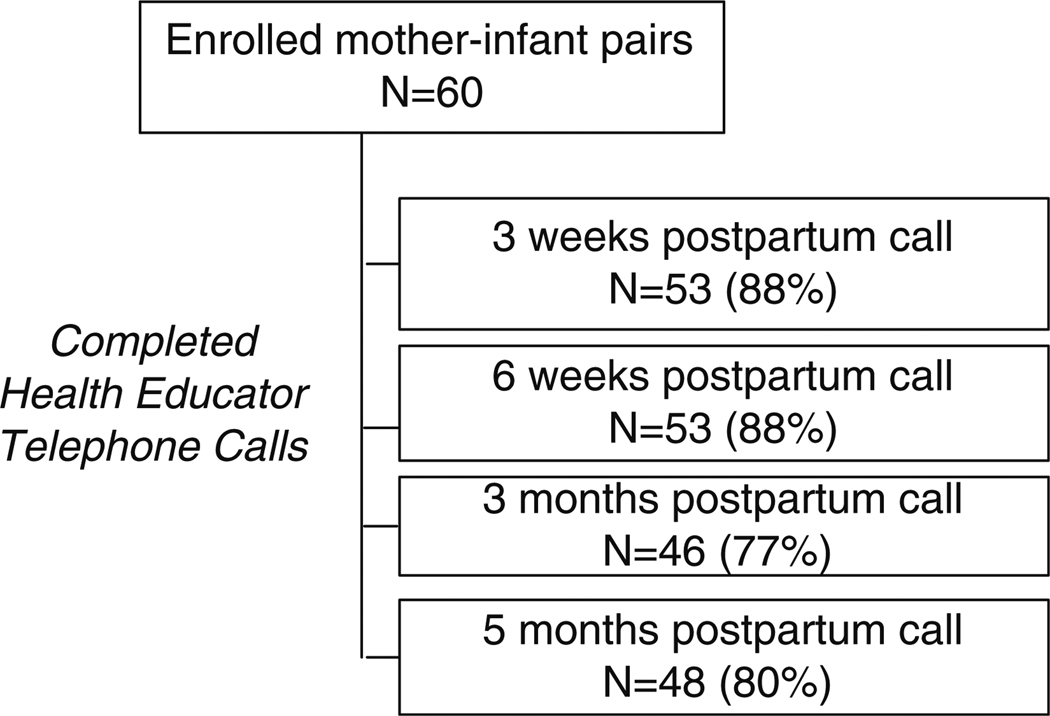

We scheduled motivational counseling calls to occur between routine infant well-child visits that are typically scheduled when the infant is 1, 2, 4 and 6 months old. The intent was to provide a booster to the intervention messages given by pediatricians at those scheduled visits. The timing of the calls is shown in Fig. 1. Calls were intended to be 15–20 min in duration. One study health educator (S.P.), trained in motivational interviewing and lactation counseling, conducted all of the study calls.

Fig. 1.

Timing and completion rates of health educator calls

For each call, the health educator reviewed behavior recommendations appropriate for the infant’s age or the mother’s postpartum stage. For example, the 3 week call focused on breastfeeding and hunger cue recommendations, and the 3 month call included introduction of solids, and physical activity for mothers.

Calls were semi-scripted and began with building rapport and an overview of the health behaviors targeted in the study (Table 1). Through pediatrician endorsement, counseling calls, and optional workshops, the intervention targeted modifiable dietary and physical activity risk factors to prevent overweight and obesity among mother-infant pairs (Table 1), selected based on national recommendations and the strength of evidence supporting a link to obesity or related health conditions. These behaviors included feeding, hunger and fullness, sleep, and television for the infants, and eating, sleep, physical activity, and television for the mothers. The study health educator used motivational interviewing (MI) techniques, such as allowing the participant to identify problematic behaviors, encouraging them to resolve ambivalence about behavior change, and assisting them in goal-setting [17–19], to help mothers identify barriers and facilitators to behavior change and to set achievable goals for themselves and their infants. MI enhances self-efficacy, increases recognition of inconsistencies between actual and recommended behaviors, and enhances motivation for change [17–19]. Additional components include assessing the importance of a particular behavior change to a participant, her readiness to change, and how confident she is about making that change [17–19].

Table 1.

Behavioral goals in the First Steps for Mommy and Me study

| Behavior | Infant goals |

|---|---|

| Feeding | |

| Breastfeeding | Exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months and prolonged duration to 12 months |

| Introduction of solid foods | Delayed introduction of solid foods to 4 to 6 months |

| Feeding behaviors | Higher responsiveness to satiety; less feeding to soothe |

| Television viewing | No TV or videos |

| TV in bedroom | No TV in bedroom |

| Sleep duration and quality | Increase nocturnal sleep duration; Decrease daytime sleep duration, settling time, night waking, and nocturnal wakefulness compared to baseline |

| Mothers’ goals | |

| Healthful diet | |

| Fast food | Avoid fast food |

| Fruit and vegetable | Increase daily intake of fruits and vegetables with a goal of 5 to 9 servings per day |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage | Avoid intake of sugar-sweetened beverages |

| Television viewing | Limit TV/video viewing to ≤ 2 h per day |

| Sleep duration | Aim for 7–8 h of sleep per day |

| Physical activity | Incorporate physical activity into daily routines; Aim for 30 min of activity each day |

Call Measures

The health educator took detailed notes during each call and following each call completed a written checklist of the content discussed and behavior recommendations reviewed, as well as call length and number of call attempts. She also wrote up a comprehensive summary of each conversation, capturing behaviors discussed, barriers and facilitators presented, responsiveness to recommendations, and her assessment of importance, confidence and readiness to change. Those accounts are the basis of this content analysis.

Analysis

Crabtree and Miller [36, 37] and others [36] have defined three data organizing styles for qualitative data analysis—immersion/crystallization, editing, and template. We used a combination of template and immersion/crystallization styles for identifying themes. The template organizing style makes use of a list of generally pre-defined themes when searching the text being analyzed. We used broad theme categories in the template related to the pre-defined topics embedded in the interview script questions. The immersion-crystallization style involved the health educator and a second independent coder’s prolonged immersion into the text and the intuitive crystallization of emerging themes. Subcategories within our pre-defined template themes were developed as they emerged from several readings of the data. Data segments related to each theme were summarized into tables by each coder independently, and then discussed to reach consensus where the categories assignment differed. In the few instances where we did not achieve consensus, another investigator (J.M.) determined the final category assignment. Further data reduction resulted in a single table of themes that were prevalent across the interviews.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 2. Women in the study were predominantly white, well educated, and of relatively high socio-economic status, with a mean age of 32.7 years. All but one participant initiated breastfeeding. The health educator completed two hundred motivational counseling calls, and Fig. 1 outlines completion rates for each of the scheduled calls. For the majority of the completed calls (66%), the health educator reached the participant on the first or second attempt. Call length averaged 17–20 min. Eighty-eight percent of participants completed either 3 or 4 of the 4 intervention calls.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 60 mother-infant pairs in the First Steps for Mommy and Me study

| Baseline characteristics | Study sample (N = 60) |

|---|---|

| Mother | % or Mean (SD) |

| Maternal age, years | 32.7 (4.6) |

| Household income < $70 K | 26% |

| Education, college graduate or more | 92% |

| Maternal race/ethnicity, White | 71% |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.1 (4.6) |

| Gestational weight gain (lbs) | 33.8 (8.3) |

| Primaparous | 63% |

| Initiated breastfeeding | 98% |

| Infant | % or Mean (SD) |

| Female | 50% |

| Birth weight, kg | 3.50 (0.45) |

| Daytime sleep duration, h/day | 7.7 (1.7) |

| TV in room where infant sleeps | 32% |

Mothers’ Perspectives on Infant Health Behavior Recommendations

Breastfeeding

Although most mothers initiated breastfeeding, over the course of 6 months they encountered many barriers to following the recommendation to breastfeed exclusively (Table 3). These barriers included frustration over feeding frequency and duration, breast pain, and concern that breast milk is not enough sustenance for their baby. Sentiments mothers expressed about breastfeeding included “feeling very tied down by it,” wishing to “have more freedom from it,” and wishing “life weren’t all about the feeding.” These issues were discouraging, and for some decreased confidence and motivation to continue breastfeeding. One mother explained that there were no barriers to continuing, “just some sacrifices,” which she accepted. After returning to work, some mothers lacked support or resources to facilitate pumping, which was prohibitive to breastfeeding exclusively beyond maternity leave. For others, the workplace was a supportive environment with a designated pumping room and a general acceptance of pumping from coworkers, which facilitated the continuation of exclusive breastfeeding.

Table 3.

Mothers’ perspectives on health behavior goals for themselves and their infants

| Infant behavioral targets | Mothers’ perspectives |

|---|---|

| Prolonged, exclusive breastfeeding | Time required makes it a burden, “wish life weren’t all about the feeding” |

| Workplace support often dictates the ability to pump and to maintain exclusivity beyond maternity leave | |

| Delayed introduction of solid foods | Concern that breast milk is not enough, particularly for larger babies |

| Confusion around when to introduce solids for exclusively breastfed babies since general messages say 4–6 months for all babies | |

| Responsiveness to hunger/satiety cues | Some cues are easy to identify (rooting, sucking on hands), but following them can still be confusing |

| Crying and fussing are often identified as hunger cues | |

| No TV for babies | Baby “isn’t really watching” |

| Try to avoid TV for babies, but they’re often in the room while others watch | |

| Improve infant sleep | Understand the rationale for non-feeding methods to soothe, but nurse to sleep, “because it’s so easy,” and mothers are so tired |

| Mothers’ behavioral targets | Mothers’ perspectives |

| Avoid fast food | Make choices out of convenience, “not the healthiest” choices |

| Return to work can be a positive change → pack lunch, snack less | |

| Increase fruit and vegetable intake | Cost, prep work, and spoiling are barriers to fruit and vegetable intake |

| Services that provide home delivery of fresh produce facilitate consumption | |

| Drink water and avoid sugar-sweetened drinks | Supporting breast milk supply is a motivator to drinking water |

| Availability of a water cooler at work boosts water consumption following maternity leave | |

| Increase physical activity time | Lack of time, and often lack of motivation are significant barriers |

| Return to work offers new opportunities to increase activity: biking and walking to work, stair climbing, exercising at lunchtime, etc. | |

| Limit mothers’ TV to 2 h or less | Feeling too tired to do anything but watch TV at the end of the day |

| Little time to watch, particularly once back at work, facilitated cutting back | |

| Increase mothers’ sleep duration | Difficult to “leave the to-do-list undone and just go to bed” |

| Help at home allowed for naps and improved nighttime sleep | |

Introduction of Solids

While more than half of the mothers followed the recommendation to wait until 6 months to introduce solid foods, many reported receiving conflicting information about when to do it. First Steps for Mommy and Me specified to wait until 6 months to introduce solids to exclusively breastfed babies and until 4–6 months for mixed or formula-fed babies, but more commonly seen is the general message to introduce solids at 4–6 months, regardless of milk type. In addition, some mothers said their pediatricians encouraged them to start solids as early as 4 months, even for exclusively breastfed infants. For some mothers, resistance to waiting to introduce solids stemmed from thinking that a bigger baby needs more than breast milk, and that a baby showing interest in food should not be denied it. One mother stated that her baby “is so interested in [parents’] food and gets upset about it,” so they started to give it to her on occasion, “because it feels mean not to.” Another planned to introduce solids at 4 months because that was when the federally funded Women, Infants and Children program (WIC) gave her cereal.

Feeding Behaviors

While most mothers were able to recognize the study-identified hunger cues (such as rooting or sucking on hands), fussiness and crying were also commonly identified as signs of hunger. One mother said she was, “feeding on demand” and described the demand as whenever the baby cried. Even when perceived cues immediately followed breastfeeding, some mothers supplemented with a bottle. One mother said that she gave her baby formula because even coming off a long time on the breast he sucked on his hands and that was his cue that he was still hungry. Another mother said that “at home [Haiti], kids stay on the breast for an hour,” so despite gaining weight well she did not think her baby was getting enough because he only stayed on the breast for 15 min.

Infant Sleep Duration and Quality

Mothers commonly nursed and rocked their babies to sleep, contrary to the intervention recommendation to avoid developing these sleep associations. They understood why it was preferable to try non-feeding methods to soothe during the night, but resorted to nursing “because it’s so easy.” One mother said she sometimes tried not to rock or feed her baby back to sleep at night, but that it was hard not to when she (mom) is so tired. All mothers wanted their babies to sleep well, and for a few this desire meant focusing on long term sleep habits, but for many it meant managing the present sleep needs of themselves and their infants.

Infant TV Viewing

In response to the “No TV for babies” recommendation, mothers fell into three categories. A few mothers had no interest in preventing their babies from watching television, some completely avoided it, and most did not have the baby watch television directly, but still had the baby in the room while the parents watched. Some went to great lengths to make sure the baby did not watch the TV while the parents watched, including erecting a barrier so the baby could not see the television. Others expressed that the baby “isn’t really watching,” although many were surprised by how strongly their babies were drawn to the television. One said she now “recognizes the power of TV” and “can’t believe how [baby] cranes her head around to look when it’s on.”

Mothers’ Perspectives on Maternal Health Behavior Recommendations

Fast Food

First Steps for Mommy and Me recommended that mothers avoid fast food, and many mothers in the earlier period of the study (3 and 6 weeks postpartum) reported not having the time, energy, or hands free to cook as barriers to following this recommendation. One mother who set goals around healthy eating said that with so much focus on the baby, “[her] own well-being has taken a back seat,” and she made choices out of convenience, “not the healthiest.” A facilitator to mothers’ healthier eating was having their own mother or mother-in-law living with them for an extended period after the birth and cooking what they generally identified as healthy and vegetable-filled meals. And while for some breastfeeding felt like a hindrance to preparing food and eating healthfully, for others it was a motivator to eat better, to pass healthy food onto their babies. For many mothers, returning to work provided structure that improved their eating. Where snacking was a common problem for mothers at home, once back at work they were more controlled in their eating, packed lunches, and felt they ate more healthfully.

Sugar-Sweetened Beverages

Many participants reported no difficulty with the recommendation to avoid sugar-sweetened beverages, indicating they already consumed few sugary drinks. Breastfeeding and wanting to support their milk supply were motivators for mothers to focus on drinking primarily water. Also, being at work encouraged water consumption since it was available in a cooler, in contrast to home where other drinks were readily available.

Fruit and Vegetable Intake

Barriers to fruit and vegetable intake included the cost, the prep work required, and spoiling. Facilitators included wanting to model good eating habits for older children, as well as Farmers’ Markets, Community Supported Agriculture weekly pre-paid produce, and other services that provide home delivery of fresh produce.

Physical Activity

“When is there time?” summed up the primary barrier for mothers to the First Steps for Mommy and Me recommendation to incorporate physical activity into their daily routines. For some, not exercising as they wanted to was frustrating, while others accepted it as unavoidable in the postpartum period and were therefore unmotivated to try to increase their activity level. For mothers who worked, the return from maternity leave offered increased opportunities for physical activity. A lunch hour provided time to walk, swim, or go to the gym, and some women could walk to work or to public transportation, take the stairs up to their office, or to get off the subway one stop early to increase their walking distance. A partner at home who supported or encouraged the mother to exercise was another great facilitator. Mothers also expressed interest in finding mom and baby exercise classes, such as Strollerfit®, as well as gyms that offered childcare.

Maternal Sleep

Help at home (husband, mother, in-laws), and a baby who slept well, were the greatest facilitators to mothers feeling they got sufficient sleep, by allowing time for naps and improved nighttime sleep. Seeing the infant’s sleep time as “the only time to get anything else done” was the most common barrier to sleeping while the baby slept. One mother stated the need to “leave the to-do-list undone and just go to bed.”

Maternal TV Viewing

The recommendation for mothers to limit their own television and video watching to less than 2 h a day received mixed responses. A sentiment repeated by mothers was that at the end of the day they were too exhausted to do anything but watch television. One mother said she and her husband had cut back on television watching because they did not want the baby exposed to it. For some mothers who were interested in reducing their own television time, a barrier was that their husbands would still want to watch. However, particularly once back at work, some mothers expressed that “time is so precious,” so they stopped watching television altogether.

Discussion

In this content analysis, we examined perspectives on goals to improve nutrition and physical activity for mother-infant pairs among women participating in a postpartum intervention that addressed these behaviors. Through this analysis, we identified several recommendations for future interventions targeting postpartum mothers and their infants (Table 4). In addition to behavioral interventions targeted to individual women, these findings may also influence policy interventions with the potential to impact many women.

Table 4.

Recommendations for intervention planning based on analysis of mothers’ comments

| Infant behavioral target | Recommendations for intervention planning |

|---|---|

| Prolonged, exclusive breastfeeding | Incorporate prenatal education to set realistic expectations around challenges and demands of breastfeeding → develop strategies to manage anticipated barriers |

| Establish both professional and peer breastfeeding support after birth to manage problems and normalize issues | |

| Worksite support is needed, including room to pump and allowance of time in which to do it | |

| Delayed introduction of solid foods | Tailor messages to feeding style; explain rationale for delaying |

| Acknowledge infant’s size with regard to timing of introduction | |

| Ask mothers what might incline them to introduce solids early | |

| Responsiveness to hunger/satiety cues | Emphasize the recognition of hunger cues and the reasoning for non-feeding techniques to soothe |

| Ask about feeding practices and respond directly to those that may be indicative of overfeeding | |

| No TV for babies | Address TV time of everyone in the household to minimize infants’ passive exposure while others watch |

| Improve infant sleep | Discuss longer term outcomes of sleep associations and engage mothers in evaluating long term sleep goals and immediate needs |

| Mothers’ behavioral target | Recommendations for intervention planning |

| Avoid fast food | Work with mothers to identify easy, nutritious meal and snack options to have available at home or bring when going out |

| Encourage planning or preparing a day’s food in advance (similar to packing lunch for work), to maintain structure and minimize impulsive eating | |

| Increase fruit and vegetable intake | Help ensure the availability of fruits and vegetables |

| Emphasize value and convenience of frozen vegetables | |

| Encourage having on hand precut or easy-to-grab vegetables and fruits of their liking | |

| Drink water and avoid sugar-sweetened drinks | Facilitate the availability of cold, filtered water |

| Distribute fun water bottles for moms to keep on-hand | |

| Increase physical activity time | Identify local exercise opportunities specifically geared to mothers, as well as fitness centers with childcare available |

| Consider workplace interventions, using the return to work period as an opportunity to take time for oneself and increase activity as a mode of transportation, or on a lunch break, or before/after work | |

| Limit mothers’ TV to 2 h or less | Facilitate thinking of ways to relax other than watching TV |

| Explore the link between mothers’ TV time and infant TV exposure | |

| Increase mothers’ sleep duration | Negotiate with mothers to find a balance between doing chores and tasks while the baby sleeps and getting themselves to sleep earlier |

We found that the early postpartum period is a challenging time for maternal health behavior change, as the women were more willing and interested to talk about behaviors and target goals for their infants than for themselves; their own “well-being has taken a back seat.” In the later postpartum months, however, the return to work offers working mothers an opportunity to shift some focus back to themselves and may provide a “window of opportunity” for health promotion for postpartum women.

Our findings of the challenges to following infant feeding recommendations were consistent with previously published literature [12, 37, 38]. It is clear that hunger cues can be hard to follow, particularly since mothers report seeing them immediately after feedings. We need further research to test mothers’ sensitivity to hunger cues in order to improve counseling around infant feeding. Mothers were receptive to infant sleep and television viewing recommendations, but expressed resistance to following them. Avoiding the methods that seemed easiest to help an infant get to sleep in the short term but may create longer-term sleep problems was a challenge also reported in a 2007 study of parent perceptions of an infant sleep intervention [25]. Other studies of physical activity for postpartum women have produced findings consistent with ours [20, 22, 39–41], showing lack of time, motivation, and childcare as barriers to physical activity. We emphasize the return to work as an untapped opportunity for improvements in maternal diet and activity.

While others have reported on interventions to promote postpartum weight loss [41–45], and on barriers to physical activity postpartum, further work was needed to identify reasons why women did not make other behavior changes as recommended. Our study offers insight into the realities of life for postpartum women and what impacts their willingness to follow intervention-based health behavior recommendations for both themselves and their infants. Some key barriers and facilitators emerged from this study that should be considered in the development of behavioral interventions for this population, but the findings also support the need to explore and address individual barriers to adherence to be able to help women work towards overcoming them. Future interventions should consider engaging women in preventive efforts beginning in pregnancy to encourage them to prioritize their own health behavior goals prior to the birth of their newborn.

When interpreting our study, several limitations should be considered. First, the educational and income levels of mothers in this study were relatively high. Our results may not be generalizable to more socio-economically disadvantaged populations. Second, the sample size and qualitative methods we used are not designed to determine the exact percentage of mothers holding any given belief. However, the themes we report here recurred in multiple interviews, supporting their salience. Additionally, mothers in the study were enrolled in an ongoing intervention to promote healthful nutrition and physical activity and their responses may have been influenced by the intervention materials they received. Although despite this, many of our findings were similar to studies that explored barriers and facilitators among postpartum women not enrolled in interventions. Finally, the data collection and analyses sections indicate two large biases in the study methodology. The data about perceptions are collected by the individual delivering the intervention. This may cause respondent bias. The data are coded by the person who delivered the intervention and who collected the data. As the data are coded into themes, the experience of this person in these two other roles may bias the identification of themes.

In summary, the postpartum period offers an untapped opportunity for health promotion among mothers and their infants. The current study focused on women participating in an intervention targeting health behavior changes, and the results could inform the design of future interventions to advance the health of mother-infant pairs in early life. To be maximally effective in improving outcomes for both mothers and infants, future interventions in this life period will need to actively engage postpartum mothers in setting their own behavior change goals.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants from Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care.

Footnotes

The abstract of this manuscript was published as part of the proceedings of The Pediatric Academic Societies’ Annual Meeting, May 1–4, 2010 in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Sarah N. Price, Email: Sarah_Price@hphc.org, Obesity Prevention Program, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 133 Brookline Avenue, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Julia McDonald, Obesity Prevention Program, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 133 Brookline Avenue, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Emily Oken, Obesity Prevention Program, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 133 Brookline Avenue, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Jess Haines, Department of Family Relations and Applied Nutrition, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada.

Matthew W. Gillman, Obesity Prevention Program, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 133 Brookline Avenue, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, USA Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Elsie M. Taveras, Obesity Prevention Program, Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 133 Brookline Avenue, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, USA Division of General Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Gore SA, Brown DM, West DS. The role of postpartum weight retention in obesity among women: A review of the evidence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(2):149–159. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunderson EP, Abrams B. Epidemiology of gestational weight gain and body weight changes after pregnancy. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2000;22(2):261–274. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohlin A, Rossner S. Maternal body weight development after pregnancy. International journal of obesity. 1990;14:159–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baird J, et al. Being big or growing fast: Systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. Bmj. 2005;331(7522):929. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38586.411273.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monteiro PO, Victora CG. Rapid growth in infancy and childhood and obesity in later life–a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2005;6(2):143–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oken E, et al. Television, walking, and diet: Associations with postpartum weight retention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taveras EM, et al. Obesity. Silver Spring; 2010. Association of maternal short sleep duration with adiposity and cardiometabolic status at 3 years postpartum. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunderson EP, et al. Association of fewer hours of sleep at 6 months postpartum with substantial weight retention at 1 year postpartum. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167(2):178–187. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taveras EM, et al. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(4):305–311. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul IM, et al. Opportunities for the primary prevention of obesity during infancy. Archives of Pediatrics. 2009;56:107–133. doi: 10.1016/j.yapd.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worobey J, Lopez MI, Hoffman DJ. Maternal behavior and infant weight gain in the first year. Journal of Nutrition Educational Behaviour. 2009;41(3):169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harder T, et al. Duration of breastfeeding and risk of overweight: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162(5):397–403. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumeng JC, et al. Television exposure and overweight risk in preschoolers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(4):417–422. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller SA, et al. Association between television viewing and poor diet quality in young children. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;3(3):168–176. doi: 10.1080/17477160801915935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Pediatrics. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, Scotland; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emmons KM, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings. Opportunities and limitations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd edn. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groth SW, David T. New mothers’ views of weight and exercise. MCN; American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2008;33(6):364–370. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000341257.26169.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter-Edwards L, et al. Barriers to adopting a healthy lifestyle: Insight from postpartum women. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:161. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornton PL, et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: The role of social support. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evenson KR, et al. Perceived barriers to physical activity among pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2009;13(3):364–375. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0359-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy HP, et al. Negotiating sleep: A qualitative study of new mothers. Journal of perinatal & neonatal Nursing. 2007;21(2):114–122. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000270628.51122.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tse L, Hall W. A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions of a behavioural sleep intervention. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34(2):162–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai YK, et al. Psychosocial factors underlying the mother’s decision to continue exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months: An elicitation study. Journal of Human Nutrition Diet. 2009;22(2):134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegney D, Fallon T, O’Brien ML. Against all odds: A retrospective case-controlled study of women who experienced extraordinary breastfeeding problems. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(9):1182–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McInnes RJ, Chambers JA. Supporting breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(4):407–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien M, Buikstra E, Hegney D. The influence of psychological factors on breastfeeding duration. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;63(4):397–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulk-Bunschoten AM, et al. Reluctance to continue breastfeeding in The Netherlands. Acta Paediatrica. 2001;90(9):1047–1053. doi: 10.1080/080352501316978147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong SK, Lee DT. Factors influencing decision to breastfeed. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;46(4):369–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taveras EM, et al. Clinician support and psychosocial risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 Pt 1):108–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taveras EM, et al. Mothers’ and clinicians’ perspectives on breastfeeding counseling during routine preventive visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):e405–e411. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald J, et al. Pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants: First steps for mommy & me. Obesity. 2009;17(S2) doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taveras EM, et al. First steps for mommy and me: A pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Matern Child Health Journal. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0696-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkan J. Immersion/Crystallization. In: MBFC WL, editor. Doing quantitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodges EA, et al. Maternal decisions about the initiation and termination of infant feeding. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gross RS, et al. Maternal perceptions of infant hunger, satiety, and pressuring feeding styles in an urban Latina WIC population. Academic Pediatr. 2010;10(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evenson KR, Aytur SA, Borodulin K. Journal of Womens Health. 12. Vol. 18. Larchmt; 2009. Physical activity beliefs, barriers, and enablers among postpartum women; pp. 1925–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebbeling CB, et al. Conceptualization and development of a theory-based healthful eating and physical activity intervention for postpartum women who are low income. Health Promotion Practice. 2007;8(1):50–59. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostbye T, et al. Active mothers postpartum: A randomized controlled weight-loss intervention trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(3):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhlmann AK, et al. Weight-management interventions for pregnant or postpartum women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(6):523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kinnunen TI, et al. Reducing postpartum weight retention–a pilot trial in primary health care. Nutrition Journal. 2007;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Toole ML, Sawicki MA, Artal R. Journal of Womens Health. 10. Vol. 12. Larchmt; 2003. Structured diet and physical activity prevent postpartum weight retention; pp. 991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amorim AR, Linne YM, Lourenco PM. Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth. Cochrane Database System Review. 2007;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005627.pub2. CD005627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]