Abstract

During the last decade, the use of micro- and nanospheres as functional components for bone tissue regeneration has drawn increasing interest. Scaffolds comprising micro- and nanospheres display several advantages compared with traditional monolithic scaffolds that are related to (i) an improved control over sustained delivery of therapeutic agents, signaling biomolecules and even pluripotent stem cells, (ii) the introduction of spheres as stimulus-sensitive delivery vehicles for triggered release, (iii) the use of spheres to introduce porosity and/or improve the mechanical properties of bulk scaffolds by acting as porogen or reinforcement phase, (iv) the use of spheres as compartmentalized microreactors for dedicated biochemical processes, (v) the use of spheres as cell delivery vehicle, and, finally, (vi) the possibility of preparing injectable and/or moldable formulations to be applied by using minimally invasive surgery. This article focuses on recent developments with regard to the use of micro- and nanospheres for bone regeneration by categorizing micro-/nanospheres by material class (polymers, ceramics, and composites) as well as summarizing the main strategies that employ these spheres to improve the functionality of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering.

Introduction

Despite extensive efforts in the field of bone tissue engineering, the use of autologous and allogeneic tissues still remains the clinical “gold standard” for bone substitution therapies. Nevertheless, the well-known drawbacks of autografts and allografts (such as short of supply, need for additional surgery corresponding to donor site morbidity etc.) are a continuous incentive to develop synthetic materials that can eventually replace auto- and allografts. Tissue engineering typically aims at reconstructing tissues by combining scaffolds composed of biodegradable biomaterials, isolated cells of the engineered tissue, or pluripotent stem cells with the addition of bioactive signals (e.g., growth factors).1 This therapeutic strategy has shown great promise in the field of bone tissue regeneration, which focuses on restoring the functionality of diseased or damaged hard tissues caused by ageing and pathological conditions.2

In this approach, three-dimensional (3D) porous scaffolds play an essential role by providing artificial extracellular matrices that mechanically and structurally support cellular activity such as cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, which finally result in bone formation. To this end, these scaffolds should be biocompatible, biodegradable without producing toxic by-products, and nonimmunogenic, while exhibiting appropriate physicochemical, topographical, and mechanical properties. In addition to acting as artificial extracellular matrix (ECM), scaffolds can also serve as a reservoir of biologically active signaling molecules with a sustained presence to the physiological environment, thereby regulating cell function and triggering tissue repair.3–5

However, conventional monolithic scaffolds that are typically combined with cells and growth factors are still far from leading to successful bone reconstruction in a clinical setting, mainly because of the limited control that can be exerted over biodegradation and drug delivery. For instance, direct incorporation of growth factors by adsorption onto bulk scaffolds normally leads to uncontrolled burst release on implantation and an overdose of growth factors that give rise to bone hyperplasia.6 A simple but effective solution for these problems has been brought forward in the 1990s by introducing microspheres as drug delivery vehicles into a continuous matrix to obtain sustained release of biomolecules without compromising the properties of the bulk scaffold.3–5,7

In that way, scaffolds of higher complexity and functionality can be designed that exhibit several advantages over conventional monolithic bulk scaffolds. First of all, micro-/nanospheres have been widely accepted as a useful tool for controlled drug delivery due to their inherently small size and corresponding large specific surface area, a high drug loading efficiency, a high reactivity toward surrounding tissues in vivo, and a high diffusibility and mobility of drug-loaded particles.3–5,8,9 Second, the size and morphology of micro-/nanospheres allow them to quickly respond to stimuli from the surrounding environment, such as temperature,10 pH,8,11–13 magnetic fields,14,15 ultrasounds, and irradiation.10 Consequently, these spheres can serve as stimulus-sensitive delivery vehicles for biologically or chemically active agents and, subsequently, establish triggered release by responding to external stimulation3. Third, by introducing spheres as porogen, the porosity of classical scaffolding materials can be significantly improved, thereby allowing for tissue infiltration into the interior of scaffolds.16 Alternatively, mechanically weak scaffolds can be stabilized by adding micro-/nanospheres as reinforcement phase17 or crosslinking agent,18 thus providing the mechanical strength that is required for bone regeneration in load-bearing applications. Fourth, micro-/nanospheres can be used as microscopic bioreactors to induce formation of apatite crystals and subsequent mineralization of hydrogels by releasing the resultant minerals, thus forming self-hardening biomaterials for bone regeneration.19 This approach is inspired by the function of matrix vesicles in human skeletal tissues, which function as microcapsules embedded in ECM to create a compartmentalized environment for the nucleation and formation of bone minerals.20 Fifth, microspheres made of cytocompatible polymers containing cell-adhesive peptide sequences can serve as a cell delivery vehicle by either cell encapsulation inside spheres or cell attachment at the exposed surface of the spheres. In that way, cell attachment sites are offered for the adhesion of anchorage-dependent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) such as osteoblasts.21 By further incorporating these cell-laden microspheres into the continuous phase of porous scaffolds or hydrogels, relatively bio-inert scaffolds can be transformed into constructs with an upgraded biological activity.22 Sixth, the spherical nature of micro- and nanospheres allows for the development of injectable and/or moldable formulations such as suspensions and (colloidal) gels to be applied by using minimally invasive surgery.23,24

In view of the points just mentioned, this article addresses the most recent developments regarding the use of micro- or nanospheres for applications in bone tissue engineering. Rather than providing preparation details of micro- and nanospheres, we have categorized micro- and nanospheres for use in bone regeneration by biomaterial class (polymer, ceramic, and composites) as well as summarized the various strategies that employ these spheres as functional components for bone tissue engineering.

Material Classification of Micro- and Nanospheres

Generally, spherical biomaterials such as micro- and nanospheres should be made of biocompatible and biodegradable materials that do not release toxic degradation products. In addition, processing of these materials should be easy to enable production of micro- and nanospheres of the desired size and morphology. To meet with these requirements, polymeric, ceramic, and composite materials have been extensively investigated.

Polymeric micro-/nanospheres

Polymeric microspheres were first introduced for biomedical applications in the 1970s, initially as a drug delivery system based on polymers derived from lactic acid. Since then, polymers have evolved as the material class that is most frequently used as a drug delivery vehicle in tissue regeneration, primarily because of their ease of processing and versatility with regard to the control over physicochemical properties (such as their degradability).

Natural polymers are of great importance for bone tissue engineering, basically due to their intrinsic biocompatibility and biodegradability. This class of polymers is often favored more than synthetic ones due to their abundant side groups in their molecular chains that allow for further functionalization. Further, natural polymers such as collagen and gelatin contain motifs such as RGD (Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid) sequences, which can modulate cell adhesion, thereby improving the cellular behavior compared with polymers that lack these cell-recognition sites. Although natural polymers often possess inherent cues for directing stem cell fate, their biological activity can be lost during processing, which may induce an immune response. On the contrary, many synthetic polymers can be considered as neutral biomaterials that can be functionalized to desire to render them instructive by promoting stem cell differentiation. Typical advantages of synthetic polymers include ease of manufacturing and modification, reasonable costs, sufficient supply, no risk of disease transfer, and strong control over polymer properties such as molecular weight and corresponding degradation rates.25 Additionally, the explicit definition of the polymeric composition and structure provides the resulting micro-/nanospheres with tailorable morphological and physiochemical properties that are beneficial for large-scale preparation and application.

Collagen

Collagen is the most extensively investigated natural polymer since the ECM of many mesenchymal tissues (including bone and cartilage) that are mainly composed of collagen as organic phase. Collagen is an attractive candidate material for bone regeneration due to its excellent biocompatibility, desirable biodegradability, and negligible imunogenicity.26,27 Collagen microspheres have been developed by using emulsification methods,28,29 in which homogenization of a water-in-oil emulsion is followed by gelation of collagen droplets resulting in spherical collagen. The resulting microspheres have been used as microcarriers for bioactive factors in bone regeneration,30–33 which showed controllable drug release kinetics by tailoring the collagen crosslinking density or by introducing bridging forces (such as electrostatic interactions) between biomolecules and the microsphere polymer network.30,32

Nevertheless, only limited progress in collagen microspheres for tissue engineering has been made most likely owing to their poor mechanical stability, suboptimal processing conditions, and possible denaturation on processing.26,27 To address this, Chan et al. developed reconstituted collagen-MSC microspheres based on the self-assembly between collagen and MSCs, which exhibited desired stability as cell delivery carriers for tissue engineering.34 In a similar approach toward stabilization of collagen, composite microspheres have been developed by blending collagen with other polymers (e.g., agarose35 and chitosan31) to improve gelation and mechanical properties. Apart from physicochemical performance, collagen extracted from animals also has the intrinsic risk of causing immune reactions and/or transmitting infectious agents.36 Therefore, recent developments in the field of bioengineered materials using recombinant collagen hold great promise for tissue engineering applications, as recombinant collagen can be a safe, predictable, and chemically defined source of collagen (by tailoring the amino acid sequence) to manufacture into materials various formulations (such as microspheres).37,38

Gelatin

As a derivative from collagen, gelatin has been widely used for biomedical applications.21,39 Superior characteristics of gelatin include beneficial biological properties comparable to collagen, ease of processing into microspheres, gentle gelling behavior, controllable degradation characteristics by tailoring crosslinking conditions, and abundant presence of functional groups that allow for further functionalization and modification via chemical derivatization. These properties make gelatin optimal for use as a delivery vehicle for drugs or proteins. Specifically, the unique electrical nature of gelatin (commercially available as both positively or negatively charged polymers at neutral pH) enables gelatin to encapsulate bioactive molecules by forming polyion complexes.21,40 In addition, biomolecules can be loaded on gelatin micro-/nanospheres by diffusional loading after preparation of the microspheres, thus separating the crosslinking step from the drug loading step. As a result, controlled and sustained release kinetics can be obtained by fine-tuning the properties of the polymeric network without exposing biomolecules to harsh conditions, such as organic solvents that can deactivate highly sensitive agents such as growth factors.24,41–44 These growth factor-laden gelatin microspheres also function as injectable fillers for the treatment of osseous defects, which have been proved to support cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation, and, subsequently, induce bone regeneration.43,45

On the other hand, gelatin nanospheres have become increasingly attractive as particulate carrier systems owing to their high drug loading efficacy, ease of surface modification, and high uptake by cells.46,47 Gelatin nanospheres can be prepared by using emulsion48 or desolvation49–51 methods. Desolvation is a process during which a homogeneous solution of charged macromolecules undergoes phase separation, and nanoparticles can be formed by following a nucleation-particle growth mechanism.49–51 Interestingly, injectable colloidal gels using gelatin nanospheres as building blocks have been recently developed in our group that are characterized by high elasticity, excellent handling properties, ease of functionalization, and cost effectiveness, which shows a great potential for tissue engineering (see Directed assembly section).52

Despite the favorable properties, critical concerns of gelatin are related to its potential to induce immunogenic responses and the poor control on its physicochemical behavior due to the animal origin. To overcome these drawbacks, microspheres made of recombinant gelatin with well-defined and tunable molecular weights, amino acid sequences (such as RGD peptides), and isoelectric points have been recently developed by using emulsion methods.53

Fibrin

Fibrin can be prepared by combining fibrinogen with thrombin, which are both derived from the patient's own blood, thereby fabricating an autologous scaffold that does not induce an excessive foreign body reaction.54 Fibrin microspheres can be prepared by using simple emulsion methods, which have been used as a platform for high-yield isolation of MSCs.55,56 Moreover, these microspheres can also serve as a construct to support in vitro MSCs expansion and osteogenic differentiation, which consequently formed a calcified matrix embedding osteoblasts,57 and further to induce ectopic bone formation58 as well as reconstruction of critical-size bone defects in vivo.59 However, the rapid degradation rate and poor mechanical stability of fibrin have been stated as the main limitation for bone tissue engineering.54 To overcome this problem, composite microspheres were developed to stabilize the fibrin matrix. Perka et al. developed alginate/fibrin composite microspheres for cell encapsulation, which solved the problems of both alginate's shortage of bioactive sequence for cell attachment and fibrin's poor capacity for cell encapsulation.60

Chitosan

Chitosan is a frequently used hydrophilic polysaccharide derived from chitin, which exhibits favorable physicochemical and biological properties for biomedical applications including biocompatibility, intrinsic antibacterial nature, and ease of processing.61 Chitosan-based micro-/nanospheres can be prepared by using various methods,62 among which emulsification has been most frequently used due to the gentle processing conditions.63 These micro-/nanospheres have been widely used as drug delivery systems for pharmaceutical or tissue engineering applications because of the abundant functional groups in the chitosan polymer backbone that allow for further functionalization,64 and the capacity of chitosan to form polyion complexes with charged proteins to obtain sustained release.65,66 Of particular interest are that chitosan-based microspheres have been used as injectable bone fillers, which can encapsulate osteoconductive mineral (calcium phosphates [CaP]) particles in the microspheres followed by ionically crosslinking using tripolyphosphate.67 In vitro studies confirmed the cytocompatibility of these chitosan-based microsphere constructs that support MSCs attachment and their subsequent proliferation and differentiation into the osteoblastic phenotype.63 Chitosan has also been processed into nanosphere formulations for targeted delivery of small biomolecules.62 Similar to microspheres, drugs or biomolecules can be loaded in chitosan nanospheres by either incorporation during particle preparation or incubation with preformed spheres. Chitosan nanospheres are a highly promising candidate for gene delivery due to a combination of the intrinsic advantages of nanoparticles (related to their exceptionally high specific surface area), the possibility to chemically modify polymer properties, and the capacity to form polyelectrolyte complexes with negatively charged DNA due to the positive charge of chitosan.62,68

Alginate

Favorable characteristics of alginate including its biocompatibility, nonimmunogenicity, hydrophilicity, and cost effectiveness, thereby making alginate highly suitable for many applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering.69,70 The most pronounced advantage of alginates relates to its gentle gelling behavior by which alginate microspheres can be formed by using ionic crosslinking in the presence of divalent cations such as Ca2+. This unique feature of alginate has facilitated widespread usage of alginate for mild encapsulation of sensitive biomolecules and/or cells.71–73 It has been shown that growth factors for bone tissue engineering loaded within alginate microspheres display controlled release kinetics,74,75 whereas cells immobilized within alginate microspheres showed a positive response when used as an injectable system for regeneration of skeletal tissue.76,77 Another attractive feature of using alginate microspheres for bone regeneration involves its intrinsic capacity to induce calcification in vivo without using biological or chemical additives. In a recent study by Lee et al., injectable calcium-crosslinked alginate microspheres mineralized in vivo by forming traces of hydroxyapatite (HAP) after being subcutaneously or intramuscularly implanted.78 The mechanism of the in vivo calcification was shown to relate to calcium ions from the crosslinked alginate hydrogel that interacted with surrounding phosphate ions to form precipitated CaP.78

On the other hand, two critical drawbacks limit alginates from further applications, that is, the poorly controllable—and often slow—degradation process on implantation in bone defects, and the lack of cell attachment sites for anchorage-dependent osteoblasts. Gamma irradiation and partial oxidation of alginate have been performed to obtain microspheres with desirable biodegradability.72,79 On the other hand, by combining alginates with components containing cell-recognition sites (e.g., fibrin60) or by modifying alginate with RGD sequences,80 alginate-based microspheres revealed a significantly improved biological response in terms of the improved adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation toward the osteogenic lineage of encapsulated cells.

Poly(α-hydroxy-esters)

Poly(α-hydroxy-esters), such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), and poly(caprolactone), are the most frequently used synthetic polymers for biomedical applications owing to their biocompatibility, hydrolytic degradation process, proper mechanical properties, ease of manufacture, and so on. Micro-/nanospheres made of poly(α-hydroxy-esters) (typically prepared by emulsification) have also been widely investigated as drug delivery vehicles or tissue engineering scaffolds with regard to bone regeneration.81–83 By fine-tuning their physicochemical characteristics including molecular weight, particle size and morphology, and surface properties, the biological performances of these polyester spheres can be controlled to a large extent, such as loading efficiency of drug/protein encapsulation, pharmacokinetics of drug release, and cell and tissue response after implantation. For instance, Jeon et al. developed heparin-functionalized PLGA nanospheres with an improved capacity for controlled growth factor delivery,84 which showed enhanced osteogenesis of stem cells in vitro and extensively improved bone formation in vivo.85 Noteworthy is that in addition to being delivery vehicles, PLGA micro- and nanospheres have recently been extensively investigated as building blocks to establish 3D tissue-engineered scaffolds (see Micro-/nanospheres as building blocks for bottom-up fabrication of scaffolds section).86,87

The disadvantages, however, of poly(α-hydroxy-esters)-based micro-/nanospheres for the widespread use in bone tissue engineering include (i) hydrophobicity resulting in poor cell adhesion and incapability of loading hydrophilic molecules or drugs, (ii) an acidic degradation product causing inflammatory tissue response and denaturation of bioactive proteins, (iii) degradation by autocatalysis leading to unpredictable degradation behavior, and (iv) low capacity of loading therapeutic components due to the harsh preparation process and limited penetration into the polymer network.88

Inorganic micro-/nanospheres

With regard to potential use of polymers in bone regeneration, it should be emphasized that most biodegradable polymers lack osteoconductivity, osteoinductivity, and mechanical strength. In contrast, inorganic biomaterials such as CaP exhibit excellent biological properties and mechanical strength resulting from their similarity to the inorganic phase of native bone tissue, which have been widely accepted as materials of choice for bone repair, and fabricated into bulk or micro-/nanoparticulate bone substitutes. To the best of our knowledge, however, only limited progress has been obtained on CaP micro-/nanospheres, as opposed to numerous researches focusing on nonspherical CaP particles,89–91 partially because of the difficulty to process CaP into spherical shape. Still, microspheres made of CaP,92–94 bioglass,95,96 or other bioactive ceramics97,98 have been developed that function as delivery vehicles for growth factors95 or as particulate bone void fillers for bone regenerative medicine.97 A versatile methodology for the preparation of bioceramic microspheres involves droplet formation of a mixture of ceramic powders and a hydrogel solution (i.e., alginate, chitosan, gelatin etc.) followed by gelation of the polymer phase that can be subsequently removed by thermal decomposition.98–101 CaP microspheres with monodispersity and controllable porosity and particle size have been developed as injectable scaffolds for bone regeneration by using this method, which supported in vitro attachment, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells that ultimately resulted in formation of microsphere-cell clusters.99 Green et al. developed calcium carbonate (vaterite) microspheres containing RGD peptide sequences, which acted as a template to stimulate mineralization and MSC differentiation in vitro, and augment in vivo bone formation in impact on bone grafting.97

Despite advantages such as ease of manufacture, low cost of production, and beneficial biological properties, inorganic micro-/nanospheres are still far from widespread use for bone tissue engineering. Plausible reasons relate to the difficulty of controlling the degradation rate, poor control over drug delivery (often related to the high affinity of bioceramics with proteins), and the propensity for growth factors to denature during adsorption to CaP.102

Composite micro-/nanospheres

Inspired by the hierarchical composite structure and unsurpassed functionality of native bone tissue, composite scaffolds that combine the advantages but eliminate the drawbacks of each component have gained considerable interest for bone regeneration over the past decades. By mimicking the organic/inorganic composition of bone, biodegradable polymers and bioactive ceramics have been combined to fabricate composite micro-/nanospheres that improve the biological performance of polymers as well as provide bioceramics with ease of processing and controllable degradation. Thus, composite microspheres have been fabricated by incorporating CaP into biodegradable polymers such as collagen,103 gelatin,104,105 chitosan,106 and PLGA107,108. These composite microspheres were shown as displaying improved performance in many aspects, such as enhanced hydrophilicity (compared with pure PLGA microspheres),109 higher drug/protein encapsulation efficiency,110 improved cytocompatibility,109 reduced biodegradation and drug release rates,104 and strongly upregulated in vitro calcifying capability.104 Further, composite nanospheres where CaP nanocrystals are incorporated into polymeric nanospheres have been synthesized by employing nanosized organic templates such as liposomes111 or polymer nanogels.112 For example, gelatin/hydroxyapatite (HAP) composite nanospheres have recently developed by biomimetically inducing HAP crystallization inside gelatin spheres under physiological conditions for applications in bone tissue engineering.113

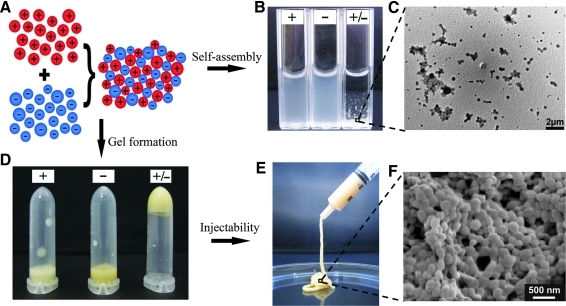

On the other hand, copolymer micro-/nanospheres have been prepared that possess advantageous properties of both polymers. Jiang et al. blended chitosan into PLGA microspheres to benefit from the neutralization reaction between chitosan and acidic PLGA degradation products, thus improving in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility and osteogenity compared with pure PLGA microspheres.65,114,115 Copolymer nanospheres can be obtained by using the coacervation technique62, in which polyelectrolyte complexation can be achieved between oppositely charged polymers. This processing method enabled the synthesis of a new class of composite nanospheres typically made of polycationic chitosan and negatively charged polymers (i.e., alginate116, dextran sulfate117, etc). These hybrid copolymer nanospheres exhibited improved physical properties (e.g., in vivo stability), desirable surface properties (e.g., hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity and surface charge),118,119 and improved pharmacological performance,116 thus resulting in better control compared with drug delivery. For instance, chitosan-PLGA and alginate-PLGA nanospheres have been newly developed as positively and negatively charged building blocks for a colloidal gels system that self-assemble due to electrostatic interactions. These gels exhibited proper injectability and negligible cytotoxicity to MSCs.119

Comparison between microspheres and nanospheres

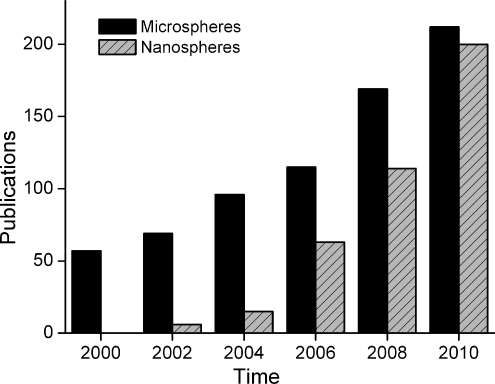

Although microspheres (defined as having diameters between 1 and 1000 μm) have been investigated for several decades in the biomedical field, the potential of nanospheres (here defined as ranging in diameter from 10 to 1000 nm) for biomedical applications has been researched over the past decade only. Both micro- and nanospheres have gained tremendous interest as reflected in Figure 1, which shows the number of publications on the use of either microspheres or nanospheres for biomedical applications over the past decade. Although the number of publications on microspheres is steadily increasing, nanospheres have been rapidly catching up with microspheres in <10 years, thus reflecting the increasing importance of nanotechnology in biomedical research.

FIG. 1.

Number of publications on the use of micro-/nanospheres for biomedical applications in the past decade by combining keywords “microspheres and biomedical” or “nanospheres and biomedical,” respectively (PubMed).

With regard to controlled delivery and tissue engineering applications, nanospheres exhibit specific advantages and disadvantages compared with microspheres. First of all, unlike particles at a micro-scale, which would release high local drug concentrations, nanospheres can be directly endocytosed, thereby allowing for accumulation of nanoparticule-encapsulated drugs. In that way, a desired therapeutic effect can be obtained with lower amounts of drugs while minimizing cytotoxicity or other undesired side effects.9,68,120 Additionally, nanospheres are capable of passing through the smallest capillary vessels (due to their inherent small size), thus avoiding rapid clearance by phagocytes so that their effective residence time in the body can be prolonged.121,122 Therefore, nanospheres are now increasingly accepted as suitable tools for potential applications based on cellular delivery, including cell imaging and intracellular gene delivery to control cell differentiation/survival.123,124 Moreover, the exceptionally high specific surface area of nanospheres broadens the range of applications related to tissue engineering. For instance, nanospheres are more competent than larger particles to serve as delivery vehicles due to their enhanced affinity to therapeutic components and quicker response to outer stimuli from the surrounding environment. Finally, nanospheres can be used as building blocks for bottom-up synthesis of colloidal systems such as injectable gels for bone regeneration. Nanosphere-based colloidal systems generally display superior properties (i.e., higher stability and better injectability/moldability) compared with microsphere-based systems owing to higher interparticle forces.52,87,125,126

Still, nanospheres also display several drawbacks compared with microspheres that are related to (i) lack of cost-effective preparation techniques for nanospheres which allow for easy upscaling without using harsh processing conditions, (ii) reduced stability under in vitro and in vivo conditions due to their intrinsic high surface area that maximizes interaction with the physiological environment, (iii) the tendency of nanospheres to aggregate into a microscale that mitigates potential benefits of the use of nanoscale particles, and, finally, (iv) unsuitability for various applications in bone tissue engineering that require micron-scale particles such as the creation of macroporosity and delivery of cells.

Strategies of Using Micro-/Nanospheres for Scaffolds Design

Generally, microspheres can be used as (i) a dispersed phase surrounded by a continuous matrix (solid polymers, hydrogel polymers, or CaP cements [CPCs]), or as building blocks to establish integral scaffolds without surrounding matrix by a bottom-up approach. In the next section, various strategies will be discussed that employ micro-/nanospheres for the design of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering with improved functionality.

Micro-/nanospheres as discrete components embedded into continuous matrices

By simply incorporating micro-/nanospheres into a continuous matrix (such as solid polymers, hydrogels, or CPCs), physicochemical and biological characteristics of these composite systems can be improved in terms of delivery of bioactive and/or chemical agents,127 porosity,16 mechanical strength,17 and cell encapsulation.22

Micro-/nanospheres embedded into solid polymers

One of the most common reasons to introduce micro-/nanospheres into solid (i.e., nonswelling) polymers is to provide bulk scaffolds with the capability of controlling the release of drugs.3–5,128,129 Especially for the delivery of bioactive molecules, the simple incorporation of growth factors into bulk scaffolds might lead to denaturation of these biomolecules due to exposure to harsh preparation conditions, hydrophobic surfaces of polymers, acidic degradation products, and so on.130 Previous studies have shown that incorporation of PLGA microspheres (as carriers for bone morphogenetic protein-2 [BMP-2]) into polyurethane scaffolds was accompanied by a reduced initial burst release followed by a sustained release of BMP-2 that promoted new bone formation compared with microsphere-free scaffolds.131

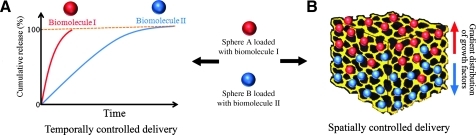

Moreover, the use of micro-/nanospheres as a delivery system allows for accurate spatiotemporal control over the release of growth factors, which are essential for successful bone regeneration by inducing osteogenesis as well as angiogenesis. To establish delivery of multiple biomolecules with programmed release kinetics, different micro-/nanosphere populations can be employed that carry various growth factors. By tailoring the physicochemical properties of these degradable spheres, distinct release behavior can be obtained, thus resulting in temporally controlled drug delivery132 (Fig. 2A). For example, dual delivery of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) was established by pre-encapsulating PDGF by using PLGA microspheres, which were subsequently incorporated into porous VEGF-containing PLGA scaffolds prepared by gas foaming technique.83 Similarly, several other studies have focused on delivery of multiple growth factors by utilizing different microsphere populations to carry various biomolecules, such as the combination of poly(4-vinyl pyridine) and alginate microspheres to load and release BMP-2 and BMP-7 independently.74

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the use of micro-/nanospheres for spatiotemporal control over delivery of bioactive molecules. (A) Spatial control of biomolecule delivery by employing a gradient distribution of micro-/nanospheres as delivery vehicles. (B) Temporal control of biomolecule delivery using micro-/nanospheres with differing release characteristics.

Besides temporally controlled delivery, to spatially control the distribution of growth factors inside the scaffolds is also of substantial importance primarily owing to the concentration-dependent effect of growth factor.133 Specifically for osteochondral tissue engineering, gradient-based bioactive signal delivery can induce both osteogenic and chondrogenic regeneration in the interfacial area.134 To this end, Wang et al. developed scaffolds containing microspheres that formed growth factor gradients through the materials for osteochondral reconstruction.135 In this study, BMP-2 and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) (that induce osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs, respectively) were encapsulated by using silk or PLGA microspheres, which were subsequently embedded into porous silk scaffolds to form reverse concentration gradients of two factors (as illustrated in Fig. 2B). This signal gradients, in turn, stimulated human MSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts and chondrocytes, respectively.135

Micro-/nanospheres embedded into hydrogels

Hydrogels made of biodegradable polymers are promising material candidates for regenerative medicine due to their unique combination of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and injectability.69,136,137 The incorporation of micro-/nanospheres into hydrogels can further upgrade the functionality of pure hydrogels from passively accepted implants to instructive and inductive scaffolds with improved physicochemical and biological properties.

First of all, the control over drug delivery kinetics is significantly improved on introduction of micro-/nanospheres into hydrogel matrices.127 Additionally, micro-/nanospheres can serve as stimulus-sensitive delivery vehicles for biologically or chemically active agents to realize triggered release in response to external stimulation.3 A representative example of this latter approach was reported by Westhaus et al., who incorporated spheres (liposomes) as functional components into alginate matrices to create stimulus-sensitive self-hardening injectables. Thermosensitive liposomes (which can be considered as nanospheres) loaded with Ca2+ ions were mixed with alginate solutions, and the gelation of the resulting mixture was subsequently induced by thermally triggered Ca2+ release from liposomes at 37°C.138 These composite systems displayed excellent flowability at room temperature, while gelling rapidly at body temperature, which confirmed the potential of this composite system for use as injectable cell-laden or acellular bone defect fillers.139 In a bioinspired approach toward tissue regeneration by using hydrogel matrices, micro-/nanosphere have also been considered as microscopic bioreactors that mimic matrix vesicles in human skeletal tissues. These vesicles act as microcapsules embedded in ECM to create a compartmentalized environment, for example, for the nucleation and formation of bone mineral.20 By mimicking this natural process, calcium and phosphate-loaded liposomes were combined with collagen hydrogels, which induced the formation of apatite crystals and subsequent mineralization of hydrogels, thus forming self-hardening biomaterials for bone regeneration.19

Further, micro-/nanospheres can serve as reinforcement components17 or crosslinking agents18 to provide hydrogels with additional mechanical support. For example, β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) microsphere/alginate composite systems encapsulating MSCs have been developed as injectable 3D constructs for bone tissue engineering, in which inorganic microspheres of high stiffness reinforced the initial mechanical strength of the composites.17 Subsequently, the degradation of β-TCP provided sustained supply of Ca2+ as crosslinking agents to decelerate the degradation of the alginate matrix. On the other hand, spheres can also induce a physical crosslinking process into hydrogel-based constructs. For instance, positively charged PLA microspheres have been utilized to form a polyion complex with anionic polyelectrolytes (such as hyaluronic acid [HA]) to induce gelation of HA without introducing reactive chemicals that can be cytotoxic.18

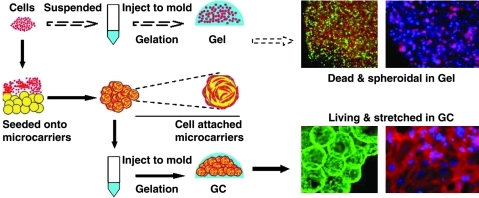

Microspheres made of biodegradable and cytocompatible polymers can serve as a cell delivery vehicle to improve the biological performance of tissue engineering constructs. Conventional hydrogel-based cell delivery has shown limited success, primarily due to the lack of sufficient adhesion of anchorage-dependent cells (such as osteoblasts) to rather inert gels such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based hydrogels. This phenomenon leads to cell death as well as the strict confinement of cells that impedes cell migration and cell-cell interactions.22 Therefore, the introduction of microspheres into hydrogels is an alternative way of providing focal adhesions and subsequent space for cell proliferation on concomitant sphere degradation.22,140–142 Wang et al. proposed an injectable osteogenic scaffold based on a cell-laden microsphere-encapsulated hydrogel using gelatin microspheres as cell carriers and agarose gels as a continuous matrix, which exhibited strong potential for cell transplantation and bone regeneration (Fig. 3).22,141,142

FIG. 3.

Experimental design and resulting photographs of two modes of cell delivery using hydrogels: cells were directly encapsulated into hydrogels to form conventional gel construct (top); alternatively, cell-laden microspheres were incorporated into hydrogels to form microsphere/hydrogel composite system (GC) (bottom). The former strategy resulted in cell death, whereas the latter one led to cell survival and proliferation in the hydrogel. Cytoskeleton F-actin (red) was counterstained with nuclei (blue). Reprinted from 22 with permission. Copyright 2011, Elsevier.

Microspheres embedded into CPCs

Although CPCs have been extensively used for bone repair and regeneration, disadvantages still exist such as slow degradation rate in vivo, lack of macroporosity, and poor capability of controlled release. To improve their performance, biodegradable polymeric microspheres (made of e.g., PLGA,16 poly(trimethylene carbonate),143 gelatin,144,145 and pectin146) have been introduced into cements. Thus, macroporosity can be introduced on degradation of microspheres, which can create space for cell and tissue ingrowth and, subsequently, accelerate the resorption of CPCs.16 The incorporation of microspheres in CPC can further enable cell delivery into cements to form cell-laden cements that might speed up new bone formation.147,148 Xu and colleagues developed a hybrid system by encapsulating stem cells in alginate biodegradable microspheres that were subsequently incorporated into CPC, thus protecting cells from excessive fluctuations in pH and electrolyte concentrations during CPC setting reaction that are known to be detrimental for cell survival.147,148

Micro-/nanospheres as building blocks for bottom-up fabrication of scaffolds

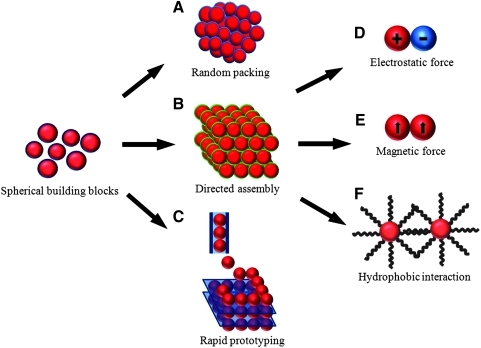

The traditional tissue engineering strategy typically employs “top-down” approach by loading a premade bulk scaffold with signaling biomolecules and cells to generate a cellularized construct that instructs toward bone tissue regeneration. This conventional approach is accompanied by several drawbacks including limited cell penetration inside the scaffolds, loss of cell viability over time, poor control over drug delivery, and suboptimal clinical handling properties.149,150 On the contrary, the so-called “bottom-up” strategy toward developing scaffolds for tissue engineering has become increasingly attractive by developing novel engineered scaffolds with precise combination of cells, biomolecules, and synthetic biomaterials. In this approach, scaffolds of high functionality can be fabricated by an assembly of micro- or nanoscale particles as building blocks. To this end, micro- and nanospheres are obvious candidates as functional units, which can be equipped with desired physicochemical and biological properties to establish constructs that mimic the function and composition of natural tissues in the body. To engineer scaffolds by using particulate building blocks, three main fabrication strategies can be discerned, that is, synthesis by random packing, directed assembly, and rapid prototyping (RP) (as illustrated in Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of using micro-/nanospheres as building blocks for bottom-up design of scaffolds by random packing (A), directed assembly (B), and rapid prototyping (C). Directed assembly can be induced by interparticle forces such as electrostatic (D), magnetic (E), and hydrophobic (F) interactions.

Random packing

Micro-/nanospheres can be randomly packed together to form a macroscopic 3D scaffold150 (Fig. 4A). This type of scaffold has been developed by using collagen,23 gelatin,24 fibrin,59 chitosan,67,151 alginate,78 and PLGA86 micro-/nanospheres as building blocks for injectable formulations. By functionalizing each type of spheres separately, the structure of the resulting scaffolds can be precisely controlled at a microscale.152 For instance, the composition and function of the scaffolds can be customized by encapsulation of signaling biomolecules,153 bioactive minerals,33,154 or by loading osteogenic cells at the outer sphere surface.

However, a critical concern of applying these microsphere-based scaffolds into bone defects is their poor integrity resulting from weak interparticle interactions, which lead to a poor mechanical stability c.q. high flowability of the scaffolds54 and migration of individual particles from defect sites on implantation.155 Therefore, different methods have been explored to preserve the agglomeration of micro-/nanosphere-based formulations at confined defect sites by using glues155 or crosslinkers.156 Another approach involves thermal fusion of polymeric microspheres into integrated macroscopic scaffolds as described by Laurencin's group by using PLGA157 and chitosan158 microspheres. The tight packing of microspheres resulted in porous scaffolds with high-pore interconnectivity, controllable pore size and amount of porosity, and mechanical properties comparable to cancellous bone.157 Further studies on these sintered microsphere-based scaffolds confirmed their capacity to release biomolecules in a controlled manner,81,134 cytocompatibility in vitro,159,160 and osteoconductivity in vivo.161

Directed assembly (self-assembling scaffolds)

Directed assembly of micro-/nanospheres into cohesive macroscopic constructs can be achieved by introducing attractive interparticle forces (such as electrostatic forces, magnetic forces, or hydrophobic interactions) (Fig. 4B). This approach overcomes the limitations of the random packing strategy and provides micro-/nanosphere-based scaffolds with enhanced structural integrity and mechanical stability. Due to the gentle physical crosslinking conditions that characterize these self-assembling systems, cytotoxic crosslinking chemicals to bridge particles are not necessary anymore. Additionally, irregular osseous defects can be filled conveniently by using micro-/nanosphere-based formulations that exhibit excellent injectable and/or moldable as well as close packing of the spherical building blocks.

Assembly driven by electrostatic interactions

Charged micro-/nanospheres have been used for more than a decade as drug delivery vehicles, because polyion complexes can be formed with charged biomolecules due to attractive electrostatic interactions. Interestingly, electrostatic forces have also been found to serve as cohesive interparticle force to induce self-assembly of micro-/nanospheres of opposite charges.87,162 Consequently, colloidal gels based on dextran microspheres or PLGA nanospheres have been developed, which show great potential as scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. These gels exhibited excellent injectability, moldability, and capability of self-recovery after shearing, due to the formation of a physically crosslinked particulate network. In addition, these colloidal gels acted as reservoirs for sustained delivery of entrapped drugs with near zero-order drug release kinetic in vitro (for PLGA nanospheres163) and stimulated osteoconductive bone formation in vivo.163 However, challenges remained for these micro-/nanosphere colloidal gels, including (i) the necessity to derivatize dextran or PLGA by chemically grafting charged groups onto the polymer backbone,125 (ii) the release of harmful degradation by-products of PLGA, (iii) the absence of cell-adhesive peptide sequences required for cell attachment, and (iv) the disruption of the network structure by screening of particle charges at a low pH or high ionic strength.162

To overcome these disadvantages, oppositely charged gelatin nanospheres have been developed by using commercially available cationic and anionic gelatin, which facilitated the fabrication of gelatin micro-/nanospheres with positive and negative charges without the necessity of additional functionalization.52 As a result, the combination of oppositely charged gelatin nanospheres gave rise to injectable and biodegradable colloidal gels with high elasticity at low nanosphere concentrations owing to electrostatic self-assembly between and tight packing of gelatin nanospheres (Fig. 5). Due to their favorable clinical handling, ease of functionalization, and cost effectiveness, these gels show great potential for application as bone fillers for tissue regeneration and/or programmed drug release of multiple biomolecules at a predetermined release rate.

FIG. 5.

Schematic diagram (A) and resulting photographs (B–F) of injectable colloidal gels based on using oppositely charged gelatin nanospheres as building blocks showing the self-assembly (B, C) and gel formation (D–F) of gelatin nanospheres of opposite charge (“+/-” denotes the mixture of oppositely charged particles) as opposed to systems made of similarly charged nanospheres (“+” and “-” denote positive and negatively charged particles, respectively). Adapted from 54 with permission. Copyright Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

Assembly driven by magnetic interactions

In view of the increasing research interest in targeted drug delivery, the potential of magnetic micro-/nanospheres has also been extensively investigated. Magnetic spheres can be prepared by entrapping magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles within or onto the surface of micro-/nanospheres.164 For instance, magnetic nanoparticles have been entrapped into dexamethasone-containing PLGA microspheres, which subsequently functioned as targeting drug carriers to provide localized and sustained drug release for the treatment of bone-related diseases.165 These magnetic delivery vehicles increase the spatial accuracy and elongate drug action due to an increased residence time at the targeting site. Further, magnetic spheres have also been used to render commercially available scaffolds magnetic,166 thus developing magnetic scaffolds that attract and uptake magnetic microcarriers loaded with bioactive agents via magnetic forces.

Similar to charged particles, magnetic micro-/nanospheres can also be used as building blocks to induce self-assembly into macroscopic constructs. Alsberg et al. combined thrombin-coated magnetic microspheres with a fibrinogen solution to form fibrin gels with defined architecture at the nanoscale in which magnetic forces had been used to position thrombin-coated magnetic microspheres in a defined two-dimensional array to guide the self-assembly of fibrin fibrils.167

Strikingly, magnetic nanospheres have also been utilized to pattern cells and form a scaffold-free cellularized structure for tissue engineering and regeneration. Magnetic cationic liposomes (MCLs) have been prepared that can be uptaken by cells via electrostatic attraction between cationic liposomes and negatively charged cell membranes.14,15 These liposome-labeled cells can be further guided by using a magnet to form complex cell patterns with 3D multilayered cellular structure.15 For example, MSCs were magnetically labeled with MCLs and cultured under the influence of a magnetic field, which induced the formation of a multilayered structure after 24 h, whereas the MSCs maintained the ability to differentiate into various cells including osteoblasts after long-term in vitro cell culture.168 Further in vivo studies revealed that these cellular constructs improved new bone formation, which confirmed the great potential of applying this scaffold-free methodology to bone tissue engineering.

Assembly driven by hydrophobic interactions

Self-assembling hydrogels based on oligolactate-grafted dextran microspheres have been developed by employing hydrophobic interactions between oligolactate chains on the surface of microspheres as the driven forces.169 The resulting microscopic network displayed high elasticity with tailorable gel properties by modifying the chemical and physical composition of the microsphere-based gels. Interestingly, the gels showed self-recovery behavior after shear thinning, which indicated that the physical crosslinking of the gel network was reversible, which is beneficial for potential use as injectable formulation in tissue regeneration.169

Rapid prototyping

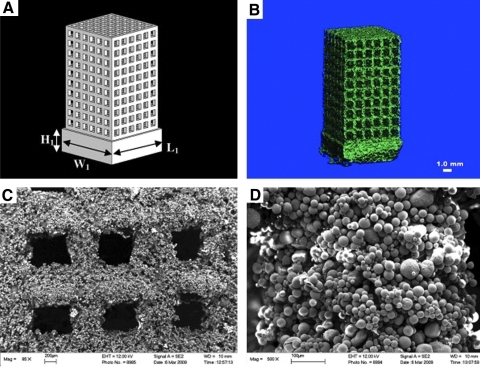

RP techniques have been recently advocated for the design of bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Using RP, constructs with customized architecture can be created from computer-aided-design data using micro-/nanospheres as building blocks to assemble into scaffolds layer by layer (Fig. 4C). For instance, microspheres consisting of polymers (such as poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) [PHBV]) or composite (such as CaP/PHBV) have been prepared by using emulsification, which were further fabricated into 3D porous scaffolds by using selective lazer sintering (Fig. 6).170,171 The resulting scaffolds exhibited an interconnected porous structure and a high amount of porosity, thereby serving as a suitable environment for osteoblastic cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation.

FIG. 6.

Scaffolds consisting of calcium phosphates/poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate composite microspheres prepared by rapid prototyping using selective lazer sintering technique. (A) Schematic diagram of the scaffold model designed by a computer; microcomputed tomography (B) and scanning electron microscopy (C, D) of the resulting scaffolds after rapid prototyping. Adapted from 170 with reproduction permission. Copyright 2011, Elsevier.

Besides the application of RP techniques for scaffold design, Mironov et al. have introduced the novel concept of 3D organ printing, in which scaffold-free cellularized tissues or organ constructs can be fabricated layer by layer by using tissue spheroids as building blocks.172,173 In continuous organ printing procedures, tissue spheroids can be dispensed with or without hydrogels as a carrier.173 This new technology may represent a viable alternative to traditional approaches in tissue engineering based on biodegradable scaffolds.

Conclusions

The potential of microspheres in bone tissue engineering has been explored for several decades, whereas nanospheres have been increasingly advocated over the past decade. Generally, microspheres can be used as either a dispersed phase surrounded by a continuous matrix (solid polymers, hydrogel polymers, or CPCs) or as building blocks to establish integral macroscopic scaffolds by a bottom-up approach without surrounding matrix. Compared with traditional monolithic scaffolds, scaffolds for bone regeneration comprising micro- and nanospheres display advantages that are related to (i) an improved control over sustained delivery of therapeutic agents, signaling biomolecules, and even pluripotent stem cells, (ii) the introduction of spheres as stimulus-sensitive delivery vehicles for triggered release, (iii) the use of spheres to introduce porosity and/or improve the mechanical properties of bulk scaffolds by acting as porogen or reinforcement phase, (iv) the use of spheres as compartmentalized microreactors for dedicated biochemical processes, (v) the use of spheres as a cell delivery vehicle, and, finally, (vi) the possibility of preparing injectable and/or moldable formulations to be applied by using minimally invasive surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support from funding KNAW, China-Netherlands Programme Strategic Alliances (PSA) (No.2008DFB50120) and the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, Applied Science Division of NWO, and the Technology Program of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (VENI grant 08101).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lee K. Kaplan D. Tissue Engineering I: Scaffold Systems for Tissue Engineering. Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salgado A.J. Coutinho O.P. Reis R.L. Bone tissue engineering: state of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4:743. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biondi M. Ungaro F. Quaglia F. Netti P.A. Controlled drug delivery in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:229. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabata Y. The importance of drug delivery systems in tissue engineering. Pharma Sci Tech Today. 2000;3:80. doi: 10.1016/s1461-5347(00)00242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouriño V. Boccaccini A.R. Bone tissue engineering therapeutics: controlled drug delivery in three-dimensional scaffolds. J Royal Soc Interface. 2010;7:209. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turgeman G. Pittman D.D. Müller R. Kurkalli B.G. Zhou S. Pelled G. Peyser A. Zilberman Y. Moutsatsos I.K. Gazit D. Engineered human mesenchymal stem cells: a novel platform for skeletal cell mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2001;3:240. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200105/06)3:3<240::AID-JGM181>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabata Y. Tissue regeneration based on growth factor release. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:5. doi: 10.1089/10763270360696941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freiberg S. Zhu X.X. Polymer microspheres for controlled drug release. Int J Pharm. 2004;282:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L. Webster T.J. Nanotechnology controlled drug delivery for treating bone diseases. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:851. doi: 10.1517/17425240903044935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collier J.H. Hu B. Ruberti J.W. Zhang J. Shum P. Thompson D.H. Messersmith P.B. Thermally and photochemically triggered self-assembly of peptide hydrogels. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9463. doi: 10.1021/ja011535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fundueanu G. Constantin M. Stanciu C. Theodoridis G. Ascenzi P. pH- and temperature-sensitive polymeric microspheres for drug delivery: the dissolution of copolymers modulates drug release. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2009;20:2465. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim E.J. Cho S.H. Yuk S.H. Polymeric microspheres composed of pH/temperature-sensitive polymer complex. Biomaterials. 2001;22:2495. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanborn T.J. Messersmith P.B. Barron A.E. In situ crosslinking of a biomimetic peptide-PEG hydrogel via thermally triggered activation of factor XIII. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2703. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ino K. Ito A. Honda H. Cell patterning using magnetite nanoparticles and magnetic force. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97:1309. doi: 10.1002/bit.21322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito A. Akiyama H. Kawabe Y. Kamihira M. Magnetic force-based cell patterning using Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide-conjugated magnetite cationic liposomes. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;104:288. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habraken W.J.E.M. Wolke J.G.C. Mikos A.G. Jansen J.A. Injectable PLGA microsphere/calcium phosphate cements: physical properties and degradation characteristics. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2006;17:1057. doi: 10.1163/156856206778366004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuno T. Hashimoto Y. Adachi S. Omata K. Yoshitaka Y. Ozeki Y. Umezu Y. Tabata Y. Nakamura M. Satoh T. Preparation of injectable 3D-formed beta-tricalcium phosphate bead/alginate composite for bone tissue engineering. Dent Mater J. 2008;27:827. doi: 10.4012/dmj.27.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arimura H. Ouchi T. Kishida A. Ohya Y. Preparation of a hyaluronic acid hydrogel through polyion complex formation using cationic polylactide-based microspheres as a biodegradable cross-linking agent. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2005;16:1347. doi: 10.1163/156856205774472353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pederson A.W. Ruberti J.W. Messersmith P.B. Thermal assembly of a biomimetic mineral/collagen composite. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4881. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson H.C. Garimella R. Tague S.E. The role of matrix vesicles in growth plate development and biomineralization. Front Biosci. 2005;10:822. doi: 10.2741/1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young S. Wong M. Tabata Y. Mikos A.G. Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules. J Controlled Release. 2005;109:256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C. Varshney R.R. Wang D.-A. Therapeutic cell delivery and fate control in hydrogels and hydrogel hybrids. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:699. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan B.P. Hui T.Y. Wong M.Y. Yip K.H.K. Chan G.C.F. Mesenchymal stem cell-encapsulated collagen microspheres for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng C. 2010;16:225. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda Y. Akiyama H. Kawanabe K. Tabata Y. Nakamura T. Treatment of experimental osteonecrosis of the hip in adult rabbits with a single local injection of recombinant human FGF-2 microspheres. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:608. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H.B. Khang G. Lee J.H. Bronzino J.D. Polymeric biomaterials. In: Park J.B., editor; Biomaterials: Principles and Applications. Boca Roton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C.H. Singla A. Lee Y. Biomedical applications of collagen. Int J Pharm. 2001;221:1. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S.-T. Park J.B. Bronzino J.D. Biomaterials: Principles and Applications. Boca Roton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. Biologic biomaterials: tissue-derived biomaterials (collagen) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swatschek D. Schatton W. Müller W.E.G. Kreuter J. Microparticles derived from marine sponge collagen (SCMPs): preparation, characterization and suitability for dermal delivery of alltrans retinol. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2002;54:125. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rössler B. Kreuter J. Scherer D. Collagen microparticles: preparation and properties. J Microencapsul. 1995;12:49. doi: 10.3109/02652049509051126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan O.C.M. So K.F. Chan B.P. Fabrication of nano-fibrous collagen microspheres for protein delivery and effects of photochemical crosslinking on release kinetics. J Control Release. 2008;129:135. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J.-Y. Kim K.-H. Shin S.-Y. Rhyu I.-C. Lee Y.-M. Park Y.-J. Chung C.-P. Lee S.-J. Enhanced bone formation by transforming growth factor-beta1-releasing collagen/chitosan microgranules. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;76A:530. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai N. Kumasaka N. Kawashima T. Kaji H. Nishizawa M. Abe T. Preparation and characterization of collagen microspheres for sustained release of VEGF. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:1891. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y.-J. Lin F.-H. Sun J.-S. Huang Y.-C. Chueh S.-C. Hsu F.-Y. Collagen-hydroxyapatite microspheres as carriers for bone morphogenic protein-4. Artif Organs. 2003;27:162. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2003.06953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan B.P. Hui T.Y. Yeung C.W. Li J. Mo I. Chan G.C.F. Self-assembled collagen-human mesenchymal stem cell microspheres for regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4652. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Batorsky A. Liao J. Lund A.W. Plopper G.E. Stegemann J.P. Encapsulation of adult human mesenchymal stem cells within collagen-agarose microenvironments. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;92:492. doi: 10.1002/bit.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynn A.K. Yannas I.V. Bonfield W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2004;71B:343. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu W. Merrett K. Griffith M. Fagerholm P. Dravida S. Heyne B. Scaiano J.C. Watsky M.A. Shinozaki N. Lagali N. Munger R. Li F. Recombinant human collagen for tissue engineered corneal substitutes. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1147. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen D. Yang C. Bodo M. Chang R. Leigh S. Baez J. Carmichael D. Perälä M. Hämäläinen E.-R. Jarvinen M. Polarek J. Recombinant collagen and gelatin for drug delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2003;55:1547. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schrieber R. Gareis H. Gelatine Handbook: Theory and Industrial Practice. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto M. Ikada Y. Tabata Y. Controlled release of growth factors based on biodegradation of gelatin hydrogel. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2001;12:77. doi: 10.1163/156856201744461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu X.H. Tabata Y. Wang C.-H. Tong Y.W. Delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor from gelatin microsphere scaffold for the frowth of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Tissue Eng A. 2008;14:1939. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan H. Zhang C. Li J. Bi L. Qin L. Wu H. Hu Y. Gelatin microspheres containing TGF-beta3 enhance the chondrogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells in modified pellet culture. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:927. doi: 10.1021/bm7013203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogawa T. Akazawa T. Tabata Y. In vitro proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stem cells cultured with gelatin hydrogel microspheres for TGF-beta1 release. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2010;21:609. doi: 10.1163/156856209X434638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel Z.S. Yamamoto M. Ueda H. Tabata Y. Mikos A.G. Biodegradable gelatin microparticles as delivery systems for the controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:1126. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tabata Y. Hong L. Miyamoto S. Miyao M. Hashimoto N. Ikada Y. Bone formation at a rabbit skull defect by autologous bone marrow cells combined with gelatin microspheres containing TGF-β1. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11:891. doi: 10.1163/156856200744084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dinauer N. Balthasar S. Weber C. Kreuter J. Langer K. von Briesen H. Selective targeting of antibody-conjugated nanoparticles to leukemic cells and primary T-lymphocytes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5898. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tseng C.-L. Su W.-Y. Yen K.-C. Yang K.-C. Lin F.-H. The use of biotinylated-EGF-modified gelatin nanoparticle carrier to enhance cisplatin accumulation in cancerous lungs via inhalation. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ethirajan A. Schoeller K. Musyanovych A. Ziener U. Landfester K. Synthesis and optimization of gelatin nanoparticles using the miniemulsion process. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2383. doi: 10.1021/bm800377w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balthasar S. Michaelis K. Dinauer N. von Briesen H. Kreuter J. Langer K. Preparation and characterisation of antibody modified gelatin nanoparticles as drug carrier system for uptake in lymphocytes. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2723. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coester C.J. Langer K. Briesen H.V. Kreuter J. Gelatin nanoparticles by two step desolvation a new preparation method, surface modifications and cell uptake. J Microencapsul. 2000;17:187. doi: 10.1080/026520400288427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shutava T.G. Balkundi S.S. Vangala P. Steffan J.J. Bigelow R.L. Cardelli J.A. O'Neal D.P. Lvov Y.M. Layer-by-layer-coated gelatin nanoparticles as a vehicle for delivery of natural polyphenols. ACS Nano. 2009;3:1877. doi: 10.1021/nn900451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang H. Hansen M.B. Löwik D.W.P.M. van Hest J.C.M. Li Y. Jansen J.A. Leeuwenburgh S.C.G. Oppositely charged gelatin nanospheres as building blocks for injectable and biodegradable gels. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H119. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuin A. Kluijtmans S.G. Bouwstra J.B. Harmsen M.C. Van Luyn M.J.A. Recombinant gelatin microspheres: novel formulations for tissue repair? Tissue Eng A. 2010;16:1811. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmed T.A.E. Dare E.V. Hincke M. Fibrin: a versatile scaffold for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng B. 2008;14:199. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rivkin R. Ben-Ari A. Kassis I. Zangi L. Gaberman E. Levdansky L. Marx G. Gorodetsky R. High-yield isolation, expansion, and differentiation of murine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells using fibrin microbeads (FMB) Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:157. doi: 10.1089/clo.2006.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zangi L. Rivkin R. Kassis I. Levdansky L. Marx G. Gorodetsky R. High-yield isolation, expansion, and differentiation of rat bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells with fibrin microbeads. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2343. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorodetsky R. The use of fibrin based matrices and fibrin microbeads (FMB) for cell based tissue regeneration. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1831. doi: 10.1517/14712590802494576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gurevich O. Vexler A. Marx G. Prigozhina T. Levdansky L. Slavin S. Shimeliovich I. Gorodetsky R. Fibrin microbeads for isolating and growing bone marrow–derived progenitor cells capable of forming bone tissue. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:661. doi: 10.1089/107632702760240571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ben-Ari A. Rivkin R. Frishman M. Gaberman E. Levdansky L. Gorodetsky R. Isolation and implantation of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells with fibrin micro beads to repair a critical-size bone defect in mice. Tissue Eng A. 2009;15:2537. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perka C. Schultz O. Spitzer R.-S. Lindenhayn K. Burmester G.-R. Sittinger M. Segmental bone repair by tissue-engineered periosteal cell transplants with bioresorbable fleece and fibrin scaffolds in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1145. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Martino A. Sittinger M. Risbud M.V. Chitosan: a versatile biopolymer for orthopaedic tissue-engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5983. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agnihotri S.A. Mallikarjuna N.N. Aminabhavi T.M. Recent advances on chitosan-based micro- and nanoparticles in drug delivery. J Control Release. 2004;100:5. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jayasuriya A. Kibbe S. Rapid biomineralization of chitosan microparticles to apply in bone regeneration. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:393. doi: 10.1007/s10856-009-3874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lao L. Tan H. Wang Y. Gao C. Chitosan modified poly(l-lactide) microspheres as cell microcarriers for cartilage tissue engineering. Colloids Surfaces B. 2008;66:218. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang T. Abdel-Fattah W.I. Laurencin C.T. In vitro evaluation of chitosan/poly(lactic acid-glycolic acid) sintered microsphere scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4894. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Laurencin C.T. Jiang T. Kumbar S.G. Nair L.S. Biologically active chitosan systems for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8:354. doi: 10.2174/156802608783790974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jayasuriya A.C. Bhat A. Fabrication and characterization of novel hybrid organic/inorganic microparticles to apply in bone regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93A:1280. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Z. Jiao Y. Wang Y. Zhou C. Zhang Z. Polysaccharides-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:1650. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Slaughter B.V. Khurshid S.S. Fisher O.Z. Khademhosseini A. Peppas N.A. Hydrogels in regenerative medicine. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3307. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Augst A.D. Kong H.J. Mooney D.J. Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6:623. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drury J.L. Mooney D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4337. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grellier M. Granja P.L. Fricain J.-C. Bidarra S.J. Renard M. Bareille R. Bourget C. Amédée J. Barbosa M.A. The effect of the co-immobilization of human osteoprogenitors and endothelial cells within alginate microspheres on mineralization in a bone defect. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3271. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Matricardi P. Meo C.D. Coviello T. Alhaique F. Recent advances and perspectives on coated alginate microspheres for modified drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:417. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Buket Basmanav F. Kose G.T. Hasirci V. Sequential growth factor delivery from complexed microspheres for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4195. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.De la Riva B. Nowak C. Sánchez E. Hernández A. Schulz-Siegmund M. Pec M.K. Delgado A. Évora C. VEGF-controlled release within a bone defect from alginate/chitosan/PLA-H scaffolds. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;73:50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Penolazzi L. Tavanti E. Vecchiatini R. Lambertini E. Vesce F. Gambari R. Mazzitelli S. Mancuso F. Luca G. Nastruzzi C. Piva R. Encapsulation of mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton's jelly in alginate microbeads. Tissue Eng C. 2010;16:141. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2008.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen B. Wei A. Tao H. Diwan A.D. Ma D.D.F. BMP-2 enhances TGF-β3 mediated chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in alginate bead culture. Tissue Eng A. 2009;15:1311. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee C.S.D. Moyer H.R. Gittens RA., I Williams J.K. Boskey A.L. Boyan B.D. Schwartz Z. Regulating in vivo calcification of alginate microbeads. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4926. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bouhadir K.H. Lee K.Y. Alsberg E. Damm K.L. Anderson K.W. Mooney D.J. Degradation of partially oxidized alginate and its potential application for tissue engineering. Biotechnol Prog. 2001;17:945. doi: 10.1021/bp010070p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alsberg E. Anderson K.W. Albeiruti A. Franceschi R.T. Mooney D.J. Cell-interactive alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. J Dent Res. 2001;80:2025. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jabbarzadeh E. Starnes T. Khan Y.M. Jiang T. Wirtel A.J. Deng M. Lv Q. Nair L.S. Doty S.B. Laurencin C.T. Induction of angiogenesis in tissue-engineered scaffolds designed for bone repair: a combined gene therapy-cell transplantation approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800069105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meinel L. Illi O.E. Zapf J. Malfanti M. Peter Merkle H. Gander B. Stabilizing insulin-like growth factor-I in poly(-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J Control Release. 2001;70:193. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richardson T.P. Peters M.C. Ennett A.B. Mooney D.J. Polymeric system for dual growth factor delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jeon O. Kang S.-W. Lim H.-W. Hyung Chung J. Kim B.-S. Long-term and zero-order release of basic fibroblast growth factor from heparin-conjugated poly(l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanospheres and fibrin gel. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1598. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim S. Jeon O. Lee J. Bae M. Chun H.-J. Moon S.-H. Kwon I. Enhancement of ectopic bone formation by bone morphogenetic protein-2 delivery using heparin-conjugated PLGA nanoparticles with transplantation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Sci. 2008;15:771. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chun K.W. Yoo H.S. Yoon J.J. Park T.G. Biodegradable PLGA Microcarriers for injectable delivery of chondrocytes: effect of surface modification on cell attachment and function. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1797. doi: 10.1021/bp0496981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Q. Wang L. Detamore M.S. Berkland C. Biodegradable colloidal gels as moldable tissue engineering scaffolds. Adv Mater. 2008;20:236. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mundargi R.C. Babu V.R. Rangaswamy V. Patel P. Aminabhavi T.M. Nano/micro technologies for delivering macromolecular therapeutics using poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) and its derivatives. J Control Release. 2008;125:193. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Uskoković V. Uskoković D.P. Nanosized hydroxyapatite and other calcium phosphates: chemistry of formation and application as drug and gene delivery agents. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2011;96B:152. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Habraken W.J.E.M. Wolke J.G.C. Jansen J.A. Ceramic composites as matrices and scaffolds for drug delivery in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2007;59:234. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.LeGeros R.Z. Calcium phosphate-based osteoinductive materials. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4742. doi: 10.1021/cr800427g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Guo Y.-P. Zhou Y. Jia D.-C. Ning C.-Q. Guo Y.-J. Mesoporous structure and evolution mechanism of hydroxycarbonate apatite microspheres. Mater Sci Eng C. 2010;30:472. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee H.-H. Hong S.-J. Kim C.-H. Kim E.-C. Jang J.-H. Shin H.-I. Kim H.-W. Preparation of hydroxyapatite spheres with an internal cavity as a scaffold for hard tissue regeneration. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:3029. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Miyauchi S. Furukawa K.S. Umezu Y. Ozeki Y. Ushida T. Tateishi T. Novel bone graft model using bead-cell sheets composed of tricalcium phosphate beads and bone marrow cells. Mater Sci Eng C. 2004;24:875. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bergeron E. Marquis M. Chrétien I. Faucheux N. Differentiation of preosteoblasts using a delivery system with BMPs and bioactive glass microspheres. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:255. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hattar S. Asselin A. Greenspan D. Oboeuf M. Berdal A. Sautier J.M. Potential of biomimetic surfaces to promote in vitro osteoblast-like cell differentiation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:839. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Green D.W. Bolland B.J.R.F. Kanczler J.M. Lanham S.A. Walsh D. Mann S. Oreffo R.O.C. Augmentation of skeletal tissue formation in impaction bone grafting using vaterite microsphere biocomposites. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1918. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu C. Zreiqat H. Porous bioactive diopside (CaMgSi2O6) ceramic microspheres for drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:820. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]