Abstract

Although fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) is widely expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), the function of FGF9 in neural development remains undefined. To address this question, we deleted the Fgf9 gene specifically in the neural tube and demonstrated that FGF9 plays a key role in the postnatal migration of cerebellar granule neurons. Fgf9-null mice showed severe ataxia associated with disrupted Bergmann fiber scaffold formation, impaired granule neuron migration, and upset Purkinje cell maturation. Ex vivo cultured wildtype or Fgf9-null glia displayed a stellate morphology. Coculture with wildtype neurons, but not Fgf9-deficient neurons, or treating with FGF1 or FGF9 induced the cells to adopt a radial glial morphology. In situ hybridization showed that Fgf9 was expressed in neurons and immunostaining revealed that FGF9 was broadly distributed in both neurons and Bergmann glial radial fibers. Genetic analyses revealed that the FGF9 activities in cerebellar development are primarily transduced by FGF receptors 1 and 2. Furthermore, inhibition of the MAP kinase pathway, but not the PI3K/AKT pathway, abrogated the FGF activity to induce glial morphological changes, suggesting that the activity is mediated by the MAP kinase pathway. This work demonstrates that granule neurons secrete FGF9 to control formation of the Bergmann fiber scaffold, which in turn, guides their own inward migration and maturation of Purkinje cells.

Keywords: fibroblast growth factor, receptor tyrosine kinase, conditional knockout, cerebellum development, granule neuron, Bergmann glia, mouse model

Introduction

The cerebellum has a unique structure consisting of folia separated by fissures. Development of cerebellum folia is orchestrated by multicellular signaling (Blaess et al., 2006; Sudarov and Joyner, 2007). At early postnatal stages, migration of cerebellar granule neurons from the external granule layer (EGL) along the Bergmann glial radial fibers to their final destination, the internal granule layer (IGL), is a critical step during cerebellar development (Goldowitz and Hamre, 1998; Komuro and Yacubova, 2003; Sotelo, 2004; Wang and Zoghbi, 2001). Perturbed granule cell migration leads to ataxic phenotypes (Chen et al., 2005). During mid-embryogenesis, the precursors of cerebellar granule neurons are born in the rhombic lip, which then migrate rostromedially to the roof of the emerging anlage of cerebellum. At the early postnatal stage, the progenitor cells of granule neurons proliferate massively in the EGL. After exiting the cell-cycle, they undergo tangential migration first, followed by inward migration along the Bergmann glial radial fibers to their final destination, the IGL. Bergmann glia are unipolar cerebellar astrocytes developed from the radial glia in the ventricular zone. They migrate to the cerebellum and align next to the Purkinje cell layer during late embryogenesis, sending out radial fibers to the pial surface during the early postnatal period (Chanas-Sacre et al., 2000). The radial fibers of Bergmann glia are shown to provide guidance for granule neuron migration and forming synapses with Purkinje cell dendrites (Yamada and Watanabe, 2002).

During the inward migration of cerebellar granule neurons, specialized junctions are formed between their cell bodies and the Bergmann glial fibers. Many glial and neuronal molecules are involved in this process, which include astrotactin (Adams et al., 2002), thrombospondin (O’Shea et al., 1990), tenascin (Husmann et al., 1992), neuregulin/erbB4 (Rio et al., 1997; Schmid et al., 2003), and Jag1/notch (Weller et al., 2006). Signal flows from granule neurons to glial cells and between Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia are essential for Bergmann glial differentiation and granule cell migration (Eiraku et al., 2005; Gaiano et al., 2000; Lutolf et al., 2002), illustrating the importance of cell-cell communication between granule cells and Bergmann glia.

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family includes 18 receptor-binding ligands and 4 FGF receptor (FGFR) tyrosine kinases (McKeehan et al., 1998). FGF7, 8, 9, 10, 14, 17, 18, and 22 have been shown to be expressed in the cerebellum, and play important roles in its development (Chi et al., 2003; Sato et al., 2004; Umemori et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2000). Aberrant signaling intensity of FGF also affects midbrain and cerebellum development at embryonic stages (Basson et al., 2008). FGF9 was initially isolated from the culture medium of the human glioma cell line (Naruo et al., 1993). Several reports indicate that in the CNS, FGF9 is predominantly expressed in neurons, and functions as a glia-activating factor (GAF) to promote the differentiation and survival of neurons and glia (Cinaroglu et al., 2005; Cohen and Chandross, 2000; Garces et al., 2000; Kanda et al., 2000; Tagashira et al., 1995; Todo et al., 1998b). Among the four FGFRs and their splice variants, FGF9 preferentially binds and activates the IIIc isoforms of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3 (Zhang et al., 2006). In the CNS, FGFR1 is expressed in both glia and neurons (Ohkubo et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2006), and FGFR2IIIC and FGFR3IIIC are primarily expressed in glial cells (Miyake et al., 1996; Pringle et al., 2003; Umemori et al., 2004).

Fgf9-null mice die at birth due to lung hypoplasia (Colvin et al., 2001). Since most developmental events of the cerebellum occur after birth, this mouse model cannot be used to address the function of FGF9 in postnatal cerebellar development. To study the biological role of FGF9 in cerebellar development, neural-specific Fgf9-knockoout mice were generated. Fgf9-mutant mice developed severe ataxia at the age of two weeks. The scaffold of Bergmann radial fibers in the mutant cerebellum was disrupted, and the IGL and Purkinje cell layers were poorly aligned. Further analyses revealed that FGF9 was secreted by neurons and required for Bergmann glia to develop radial fibers, and that the FGF9 functions in the developing cerebellum were primarily mediated by FGFR1 and FGFR2. This work establishes FGF9 as a neuronal messenger that instructs the differentiation of Bergmann glia and regulates the inward migration of cerebellar granule neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animals were housed in the Program of Animal Resources of the Institute of Biosciences and Technology, and were handled in accordance with the principles and procedures of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The mice carrying LoxP-flanked Fgf9 (Fgf9flox) (Lin et al., 2006), Fgfr1 (Fgfr1flox) (Trokovic et al., 2003), and Fgfr2 (Fgfr2flox) (Yu et al., 2003), Fgfr3 null (Fgfr3null) (Deng et al., 1996), Fgfr4 null (Fgfr4null) (Weinstein et al., 1998), Nestin -Cre(Tronche et al., 1999), hGFAP-Cre (Zhuo et al., 2001), and the ROSA26 reporter (Soriano, 1999) alleles were bred as described in (Lin et al., 2006). Genotypes of the mice bearing the floxed, conditional null, and wildtype Fgf and Fgfr, as well as the ROSA26 reporter alleles, were determined by PCR analyses as described in (Lin et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2007; Soriano, 1999; Trokovic et al., 2003; Weinstein et al., 1998).

Primary cerebellar neuronal and glial cultures

Primary glia and neurons were purified from mouse cerebella at postnatal day 6 as described (Hatten, 1985; Rio et al., 1997) with minor modifications. The dissected cerebellum was minced in PBS, followed by incubation with 0.25% trypsin (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 0.1% DNase I (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 10 minutes at 37°C. After trituration, cells were preplated on an uncoated Petri dish for 20 minutes to remove fibroblasts. Unattached cells were collected, resuspended in PBS, and applied to a cold two-step Percoll gradient (35–60%) centrifugation at 3300 RPM for 10 minutes. Astroglia were recovered from the top and neurons from the interface. The recovered neurons were then resuspended in DMEM/F12 (1:1) medium with 10% horse serum. Contaminant glia were further removed by plating on 6-well tissue culture plates coated with 25 μg/ml of Poly-D-Lysine for 3 times. After incubation for 45 minutes at 37 °C, non-adherent neuron cells were collected and cultured on Poly-D-Lysine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) coated cover slips placed in a 24-well plate. The recovered astroglia were resuspended in the same medium. The contaminant fibroblasts were further removed by preplating on an uncoated 6-well plate for 30 minutes. The non-adherent cells were cultured on coated 24-well plates. Recombinant human FGF9 or FGF1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to the culture medium at a final concentration of 20 ng/ml for 48 hours with or without 10 μM PI3 kinase inhibitor (LY294002) or ERK1/2 inhibitor (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analyses

Dissected brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 4 hours, dehydrated in ethanol, and paraffin-embedded. All sections were collected. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for morphological studies. For immunostaining, sections were subjected to an antigen-retrieval by autoclaving in Tris-HCl buffer (PH 10.0) for 5 minutes or as suggested by manufacturers of the antibodies; the primary cultures were permeablized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 6 minutes. The samples were then incubated with the blocking solution, followed by primary and secondary antibody incubations. The sources and concentrations of primary antibodies are: mouse anti-Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) (1:400 dilution), rabbit anti-Calbindin D-28K (EG-20) (1:4000 dilution), and mouse anti-PCNA (1:1000 dilution) from Sigma Co (St. Louis, MO); goat anti-Vimentin (C-20) (1:50 dilution), goat anti-GABAA Receptor α6 (N19) (1:50 dilution), and rabbit anti-p27 (M-197) (1:50 dilution), rabbit anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (1:200 dilution), mouse anti-FGF9 (D8) (1:20 dilution) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruz, CA); mouse or rabbit anti-neuronal class III β-tubulin (clone Tuj1) (1:250) from Covance (Berkeley, CA).

For Western blot assays, the primary glia were cultured in DMEM with 10% horse serum for 48 hours followed by 5-hour serum starvation. Where indicated, PI3 kinase inhibitor or ERK1/2 inhibitor was added to the culture medium 1 hour prior to FGF treatment. The cells were treated with FGF1 or FGF9 for 10 minutes and then lysed by the RIPA buffer. The sources and concentrations of antibodies were: rabbit anti-phosphorylated AKT (1:1000) and anti-phosphorylated ERK1/2 (1:1000) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); mouse anti-β-actin (1:3000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.

BrdU incorporation analysis

BrdU (5- bromo-2′-deoxyuridine, Sigma Co, St. Louis, MO) was intraperitoneally injected into mice (0.05 mg per 10 g body weight) at the indicated days. At 2–3 hours post injection, the mice were sacrificed, and the brains were collected for the analyses. Briefly, brains were fixed in 4%PFA for 4 hours, paraffin-embedded and sectioned. The incorporated BrdU was detected by immunostaining with anti-BrdU antibody (1:1000 dilution; Sigma Co, St. Louis, MO) according to manufacturer’s suggestions.

Quantitative RT-PCR analyses

For RT-PCR analyses, total RNA was extracted from fresh brains or primary cultured cerebellum cells with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcriptions were carried out with SuperScript II (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and random primers according to protocols provided by the manufacturer. The RT-PCR for FGF9 expression was carried out for 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 minute, 56 °C for 1 minute and 72 °C for 1 minute with Taq DNA Polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) with the primer as described (Lin et al., 2006). RT-PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels, and the representing data from at least three repetitive experiments were shown. Real-time RT-PCR analyses were carried out with the SYBR Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMix (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as suggested by the manufacturer. The primer sequences are: Notch1: CCCACTGTGAACTGCCCTAT and CACCCATTGACACACACACA; ErbB4: ACCTCTCCTTCCTGCGGTCTATC and TGTTCTGGTCTACATAGACTCCA; CDK5: ACTCATGAGATTGTGGCTCTGAA and AGGTCACCATTGCAGCTGTCGAA; BLBP: CACAGAGATCAATTTCCAGCTGG and TCATAACAGCGAACAGCAACGAT; Neuregulin: AGAACACCCAAGTCAGGAACTCA and CACCAGTAAACTCATTTGGGCAC; NeuroD: AACCGCATGCACGACCTGAAC and GAAGTTACGAGAGTTCAGCTGC; Neurog1: AGGCGCTGCTGCACTCGCTG and TGATCTGCCAGGCGCAGTGTC; Neurog2: TGATGCACGAGTGCAAGCGTC and CCAGATGTAATTGTGGGCGAAG; Astrotactin: GTGCTGGAGATCTCAGGGAATAC and ATAGCAACAGAGCGATCATGCCA; class III β-tubulin: CAAAGGTGGCTAAAACGGGGAG and TATGAAGATGACGACGAGGAGTC. Relative abundances of the mRNA were calculated using the comparative threshold (CT) cycle method, normalized with β-actin, and are expressed as fold of differences between Fgf9cnNestin and control cells. The final data show means (±SD) of three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Deleting the Fgf9 gene in the CNS causes ataxia

To investigate the role of FGF9 in neural development, the LoxP-Cre recombination system was employed to specifically delete the Fgf9 allele in neural precursors at E 10.5 by crossing Fgf9flox mice (Lin et al., 2006) with NestinCre transgenic mice (Tronche et al., 1999). Deletion of the floxed sequence resulted in a defective Fgf9 allele lacking the translational initiation site and exon 1 coding sequences (Fig 1A). RT-PCR analyses showed that the RNA expression level of Fgf9 was dramatically reduced in the Fgf9 conditional null (Fgf9cnNestin) brains compared to the wild-type (WT) and Fgf9 flox/flox (F/F) controls (Fig. 1B). X-Gal staining of the NestinCre/R26R-lacZ bigenic mice showed no evidence of mosaic Cre activity in the CNS as previously reported (Tronche et al., 1999) (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Conditional knockout of Fgf9 in the CNS causes ataxic phenotypes.

A. Schematic diagram describes the design of floxed and conditional null Fgf9 allele. Coding exons are shown in black boxes and non-coding exon sequences in open boxes. Primers f1, f2 and f3 are used for genotyping; f4 and f5 are used for RT-PCR analyses. B. RT-PCR analyses demonstrate a decreased Fgf9 expression in the Fgf9cnNestin (CNNestin) cerebellum compared to the wild-type (WT) and Fgf9flox/flox (F/F) controls at 3 weeks of age. Gapdh was used as internal loading controls. C. Fgf9cnNestin mice have paroxysmal hyperextended hind limbs with chronic spasms. The arrows indicate that hind limbs of 3-week-old CNNestin mice were extended outward. D. When suspended by the tail, the limbs and digits of CNNestin mice were often retracted and clasped, whereas the F/F mice usually extended their limbs and digits. E. CNNestin mice show ataxic gaits that lack the forefoot-hindfoot correspondence seen in control mice. The front paws were labeled with red ink and rear paws with blue ink. Arrows indicate the direction of movement. F. CNNestin mice exhibit growth retardation from postnatal day 15. Data represent means ± sd of triplicate samples.

The Fgf9cnNestin pups appeared normal within the first week after birth. From the middle of the third week, they began to show ataxic symptoms, such as clumsy movement, abnormal posture, and impaired balance. The hind limbs of Fgf9cnNestin mice were hyper-extended with chronic spasms, which caused tremor and frequent falls (Fig. 1C and Supplemental video 1). Most of the Fgf9cnNestin mice, when suspended by the tail, had their limbs withdrawn and digits clasped (Fig. 1D, right panel), which was in clear contrast to the extended extremities of the control mice (Fig. 1D, left panel). Images of inked foot prints showed that the Fgf9cnNestin mice had ataxic gaits that lacked the forefoot-hindfoot correspondence (Fig. 1E). From the third week after birth, the Fgf9cnNestin mice began to show growth retardation, a characteristic of ataxia. On average, adult Fgf9cnNestin mice were 30% less in body weight than their control littermates (Fig. 1F). For all the described phenotypes, the Fgf9flox/flox mice appeared indistinguishable from the WT mice and, therefore, were used as the control throughout this study.

Fgf9 ablation disrupts granule neuron migration during cerebellum development

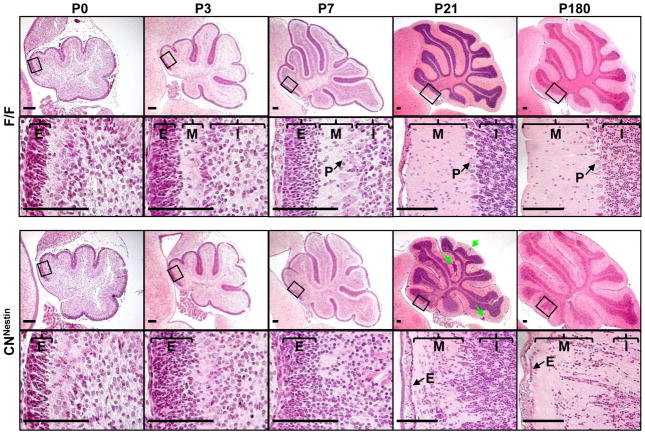

The ataxic phenotype suggests that the Fgf9cnNestin mice might have defects in the cerebellum. To test this possibility, the cerebellum was examined at different postnatal days (Fig. 2). Grossly, the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum was foliated and normal in size. Histologically, the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum was the same as the control at P0. From P3 to P7, the mutant EGL appeared thicker than the control, and had increased numbers of granule cells in the molecular layer (ML) and ill-defined EGL-ML boundaries. At P21, all the granule cells in the control mice had migrated into the IGL, whereas in the mutant cerebellum, many granular neurons remained in the EGL and ML (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2). Such defects persisted in 6-month or older mice. These results point out that Fgf9 knockout causes defects in the migration and/or differentiation of cerebellar granule neurons.

Fig. 2. Fgf9 ablation disrupts the migration and alignment of cerebellar granule neurons.

H&E staining of midsagittal sections of the F/F (top two rows) and CNNestin (bottom two rows) cerebellum from postnatal day 0 (P0) to P180. Higher magnification views of the framed areas in the low-magnification images in rows 1 and 3 are shown in rows 2 and 4. Clusters of granule cells were found in the molecular layer (M) of CNNestin mice (indicated by green arrows). The alignment of Purkinje cells was also disturbed in mature cerebella. E, external granule layer; internal granule layer; P, Purkinje cells. Scale bar, 20 um.

Ablation of Fgf9 extends the proliferation window of granule neurons without disrupting their final maturation

To dissect how FGF9 affects the proliferation of cerebellar granule neurons, we first examined the expression patterns of PCNA, a proliferative cell marker, in the control and Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum. The results showed that the ratio of PCNA-positive cells in the Fgf9cnNestin EGL was not significantly different from that in the control EGL at or before P10 (Fig. 3Aa, 3Ab). This result was confirmed by the BrdU incorporation and phosphorylated histone H3 assay (Supplemental Fig. 3). At P21, when control granule cells had finished dividing and migrated to the IGL, some granule cells were still PCNA positive in the mutant EGL, suggesting that the proliferative window of mutant granule neurons was extended (Fig. 3Ac). Immunostaining of P27kip1, a postmitotic marker, revealed that postmitotic cells were scattered throughout the EGL and ML of the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum, unlike the control cerebellum where most of the postmitotic granule neurons had migrated out of the EGL and ML at P21 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Fgf9 knockout prolongs the proliferation window of granule neurons without affecting their final maturation.

A&B, Midsagittal sections of the F/F and CNNestin cerebellum at the indicated age were immunolabeled with (A) anti-PCNA antibody for proliferative cells or (B) anti-p27kip1 antibody for postmitotic cells and counterstained with hematoxylin for the nuclei. At P21, the CNNestin cerebellum still had a thin layer of PCNA-positive cells in the EGL (Ac) and displaced postmitotic granule cells in the ML (Bb). C. Immunostaining of anti-GABAA α6 revealed that the ectopic granule cells in the ML also expressed a mature granule cell marker, GABAA α6 (indicated by arrows) at P21. D. TO-PRO3 staining shows the nuclei of neuron and glia cells. The nucleus of both F/F and CNNestin granule cells, which makes up the majority of cells, is elongated in the molecular layer (indicated by arrows).

GABAA receptor subunit α6 (GABAA-Rα6) is expressed by the mature granule cells after they reach their final destination (Mellor et al., 1998). Immunostaining showed that those ectopically localized granule cells in the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum also expressed GABAA-Rα6 at P21 (Fig. 3C), indicating that FGF9 depletion did not abort the expression of mature granule neuron markers. During the migration through the molecular layer, most control granule cells displayed a fusiform nucleus that was aligned perpendicularly to the IGL (Fig. 3D, top panel). Although most Fgf9 null granule cells still had a fusiform nucleus, the mutant migrating cells were misaligned (Fig. 3D, bottom panel), suggesting that the intrinsic program for changing cell shape was not affected by Fgf9 ablation. Together, the results demonstrate that ablation of Fgf9 disrupts the migration and extends the proliferative window of cerebellar granule neurons without severely disrupting their intrinsic differentiation program.

Loss of Fgf9 disrupts the alignment and dendritic arborization of Purkinje cells

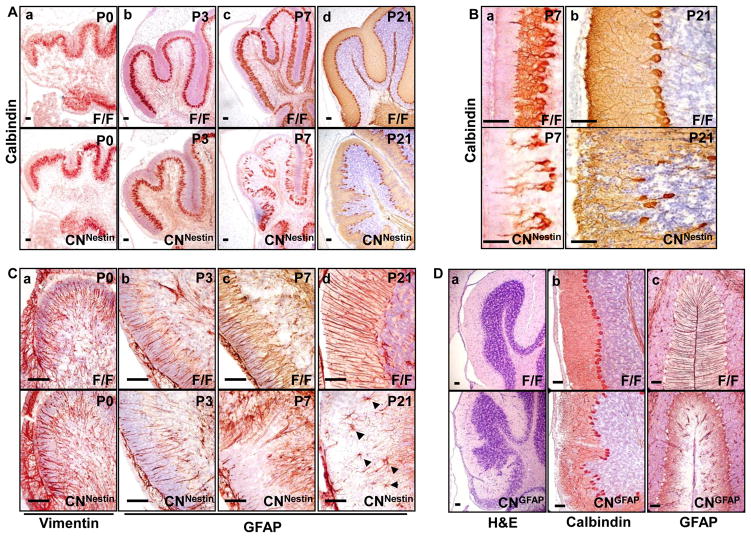

Unlike the control cerebellum where the Purkinje cells were always positioned as a single layer between the IGL and ML, the organization of mutant Purkinje cells was disrupted in the mature Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum (Fig. 2). Immunostaining of a Purkinje cell marker, calbindin, showed that, similar to the controls, mutant Purkinje cells formed a single layer beneath the EGL and began to extend the dendrites into the ML at P0 (Fig. 4A). The results suggest that ablation of Fgf9 does not affect the prenatal development of Purkinje cells. However, starting from P3, although mutant Purkinje cells exhibited elongated primary dendrites as in the controls, many mutant Purkinje cells did not exhibit their secondary dendrites and the soma alignment was disrupted (Fig. 4A, B). Thus, the results also suggest a role of FGF9 in Purkinje cell maturation.

Fig. 4. Ablation of Fgf9 also affects the development of Purkinje neurons and Bergmann glia.

A. Impaired Purkinje cell alignment and arborization in cerebella deficient in Fgf9. Purkinje cells of control and mutant cerebellum from P0 to P21 were immunostained with anti-Calbindin antibody. B. Enlarged views of the P7 and P21 cerebellum. The alignment of mutant Purkinje cells (CNNestin) was disorganized. They had elongated primary dendritic bundles and reduced dendritic arborization compared to the control (F/F). C. Midsagittal sections of cerebella were immunostained with anti-vimentin or anti-GFAP antibody for Bergmann glia. The radial fibers of Bergmann glia in the CNNestin cerebellum were poorly developed and failed to reach the pial surface. At P21, some glia in the CNNestin cerebellum exhibited a stellate morphology (arrowheads). D. Defective cerebellum in Fgf9cnGFAP (CNGFAP) mice, in which the Fgf9 alleles were intact in Purkinje cells but deleted in the Bergmann glia and granule neurons. Midsagittal sections of the CNGFAP cerebellum at P21 were stained with H&E or the indicated antibodies. Note that the granule cell migration, Purkinje cell alignment and arborization, and Bergmann glial radial fiber formation were all impaired, indicating that the Purkinje cell-made FGF9 alone is not enough to guarantee normal cerebellar development.

The formation of radial fiber scaffold of Bergmann glia is perturbed in the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum

Inward migration of granule neurons is guided by the Bergmann glial fibers. To investigate whether Fgf9 ablation affected the formation of the radial glial scaffold, anti-Vimentin (P0, Fig. 4Ca) and anti-GFAP (P3 and later, Fig. 4Cb-d) immunostainings were used to determine the Bergmann glial fiber development at different postnatal stages. The cell bodies of Bergmann glia in the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum appeared misplaced at P3 or later, but not at P0. Many Bergmann glial fibers in the mutant cerebellum completely lost their contact with the pial surface. At P21, many GFAP-positive cells with a stellate morphology were found in the ML of mutant cerebellum (Fig. 4Cd, bottom panel).These results demonstrate that FGF9 is required for formation of the radial fibers, as well as for the alignment of Bergmann glia cell bodies during the expansion of the cerebellum.

To determine if the migration phenotypes of Fgf9cnNestin mice depend on FGF9 secreted by Purkinje cells, the hGFAP-Cre driver (Zhuo et al., 2001), which expresses the Cre recombinase in the granule cells and Bergmann glia, but not the Purkinje cells (Supplementary Fig. 1), was employed to ablate the Fgf9 alleles in the granule cells and Bergmann glia (designated as Fgf9cnGFAP). These Fgf9cnGFAP mice developed the same ataxic symptoms (data not shown), and exhibited all the characteristic defects in the formation of Bergmann glia radial fibers, granule cell migration, and Purkinje cell alignment and maturation as the Fgf9cnNestin mice (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that endogenous FGF9 secreted by Purkinje cells is not sufficient for the cerebellum to maintain the normal structure.

Granule neuron-derived FGF9 is required for cerebellar glial cells to develop radial morphology

Primary glial and granule cell cultures were used to determine the cell types secreting and affected by FGF9. When cultured alone, the majority of Fgf9cnNestin or control glia exhibited a stellate morphology (Fig. 5Aa). After receiving human recombinant FGF9 treatment, both Fgf9cnNestin and control glia developed uni/bipolar radial processes characteristic of the radial glia in vivo (Fig. 5Ab). These results showed that FGF9 is essential to instruct the cerebellar glia to adopt the radial morphology. To determine whether this phenotype depended on the FGF9 produced by neurons or glia, Fgf9cnNestin and control glial cells were cocultured with either the Fgf9cnNestin granule neurons or the control neurons (1 glia per 5–10 neurons) (Fig. 5B). The results demonstrated that the control granule neurons were able to induce the uni/bipolar morphology of control and mutant glia (Fig. 5Ba, 5Bb, top panels). In contrast, coculture with the Fgf9cnNestin neurons failed to elicit such effects, regardless of the Fgf9 genotype of the glial cells (Fig. 5Bc, 5Bd, top panels). On the other hand, as revealed by Tuj1 staining, no obvious difference in axon or dendrite extension was observed between mutant and control granule cells, with and without being co-cultured with control or mutant glias (Fig. 5B, bottom panels). Real-time RT-PCR assays showed no significant difference in the expression of differentiation markers between Fgf9cnNestin and control neurons or glia, except for BLBP (Fig. 5C), which was expressed by radial glia and significantly reduced in the Fgf9cnNestin glia. The results confirm that ablation of Fgf9 disrupts the differentiation of Bergmann glia but not that of granule neurons.

Fig. 5. Granule neuron-derived FGF9 is essential for the development of radial morphology of cerebellar glia.

A. Glia cells were isolated from the F/F and CNNestin cerebellum, cultured with or without exogenous FGF9 (20 ng/ml) for 48 hours, and stained with anti-GFAP antibody. (a) Without FGF9, both control and mutant glial cells exhibited a stellate astrocytic morphology. (b) FGF9 treatment induced a morphological change in both F/F and CNNestin glia from stellate to radial shapes. Inserts, high magnification views from the same slides. B. Control and mutant granule neurons (N+ and N−) or glia (G+ and G−) were prepared separately from the F/F and CNNestin cerebellum and cocultured for 48 hours in different combinations. Glia and neurons were stained with anti-GFAP and Tuj1 antibodies, respectively. Both F/F and CNNestin glia exhibited a radial morphology when being cocultured with F/F granule cells (N+), and a stellate morphology when being cocultured with CNNestin granule cells (N−). The percentages of glia with radial morphologies were measured from 3 individual experiments (mean ± sd). C. Expression of neuronal and glial markers was assessed by real-time RT-PCR. Total RNAs were extracted from the control or mutant cerebellar neurons or glia. β-actin expression was used as an internal control. Each bar represents the average (± sd) of 3 independent experiments. NRG, neuregulin; Ngn1, neurogenin 1; Ngn2, Neurogenin 2; ASTN, astrotactin. D. Expression of FGF9 in the cerebellum at the indicated ages. In situ hybridization showed that Fgf9 mRNA was predominantly located in neurons including Purkinje and granule cells. Immunostaining demonstrated that FGF9 protein was broadly distributed in the cerebellum, including neurons and Bergmann glial radial fiber scaffold. Note that both in situ and immunostaining signals were significantly reduced in Fgf9 mutants.

To further characterize the origin of FGF9 in the cerebellum, in situ hybridization and immunostaining with anti-FGF9 antibodies were employed to examine Fgf9 expression at the mRNA and protein levels in the cerebella. The results revealed that Fgf9 mRNA was predominantly expressed in neurons, including Purkinje cells and granule cells (Fig. 5Da), and that FGF9 proteins were wildly distributed in both neurons and the Bergmann glial scaffold (Fig. 5Db).. The results are consistent with previous reports (Nakamura et al., 1999; Tagashira et al., 1995; Todo et al., 1998a). Together, the results show that the neuron-derived FGF9 is essential for Bergmann scaffold formation.

FGFR1 and FGFR2 redundantly mediate the FGF9 activities on Bergmann glia differentiation via the MAP kinase pathway

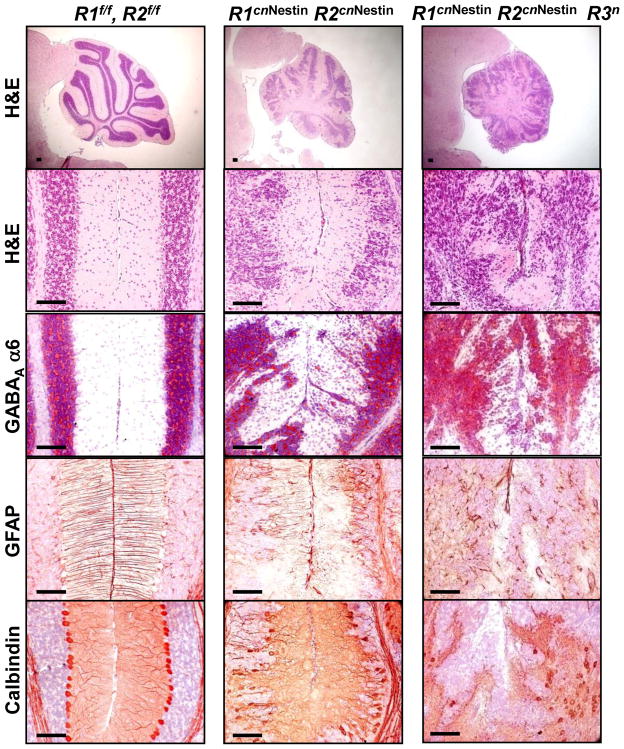

Among the four FGFRs, FGF9 preferentially binds to the IIIc isoform of FGFR1, 2 and 3. Histological data showed that deleting any single one of the Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3 or Fgfr4 gene would not produce any observable defect in the cerebellum (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting overlapping activities of these different receptors in cerebellar development. To investigate which FGFRs are required for cerebellar development, mice deleted of multiple Fgfr alleles were generated. While the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr3null and Fgfr2cnNestin/Fgfr3null double mutants showed normal cerebellar development (Supplementary Fig. 4), the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin double conditional null mice exhibited ataxic symptoms by the age of 3 weeks and older. Similar to the results of Fgf9cnNestin mice, the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin cerebellum also exhibited defects in granule cell migration, Bergmann fiber scaffold formation, and Purkinje cell alignment (Fig. 6). It is worth noting that the cerebellar defects in Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin mice were more severe than those in Fgf9cn mice, and the triple knockout mice (Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin/Fgfr3null) developed even more severe phenotypes than the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin double knockout mice (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. FGFR1 and FGFR2 redundantly regulate formation of the Bergmann radial fiber scaffold.

The floxed Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 alleles were deleted by the Nestin-Cre driver. Midsagittal sections of the cerebellum prepared from the homozygous Fgfr1flox/flox and Fgfr2floxflox (R1f/f, R2f/f), Fgfr1/Fgfr2 double conditional null (R1cnNestin/R2cnNestin), and Fgfr1/Fgfr2/Fgfr3 triple null (R1cnNestin/R2cnNestin/R3n) mice at P21. Each panel was labeled with H&E, anti-GABAA α6, anti-GFAP, and anti-calbindin antibodies. A combined deletion of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2, but not that of Fgfr1/Fgfr3 or Fgfr2/Fgfr3, caused defects in the cerebellar development similar to but more severe than those caused by Fgf9 knockout.

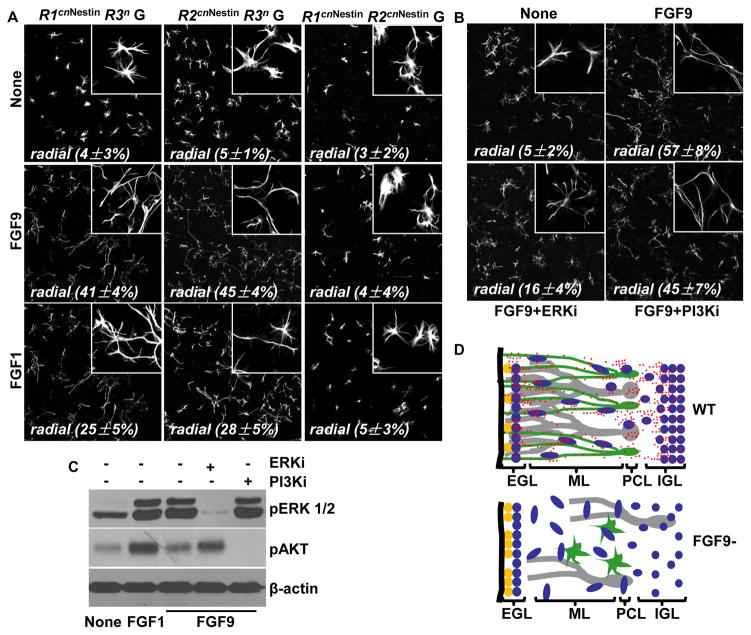

To determine if FGFR1 and FRFR2 mediated the FGF9 functions on the developing cerebellum, cerebellar glia isolated from the FGFR-knockout mice were treated with FGF9 or FGF1 (Fig. 7A, middle and lower panels, respectively). The results showed that both FGF9 and FGF1 were capable of restoring the radial morphology in the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr3null (Fig. 7Aa) and Fgfr2cnNestin/Fgfr3null (Fig. 7Ab) glial cells but not in the Fgfr1cnNestin/Fgfr2cnNestin cells (Fig. 7Ac). Together, the results demonstrate that the FGF9 activities in cerebellar development are redundantly mediated by FGFR1 and FGFR2 expressed by Bergmann glia cells, and that additional FGFs, such as FGF1, are also involved in this process.

Fig. 7. The activity of FGF9 to induce radial morphology in cerebellar glia requires either FGFR1 or FGFR2, and the MAP kinase pathway.

A. Glia cells were prepared from R1cnNestin/R3n, R2cnNestin/R3n, or R1cnNestin/R2cnNestin cerebellum, cultured in the absence or presence of FGF9 (20 ng/ml) or FGF1 (20 ng/ml) for 48 hours, and stained with anti-GFAP antibody. Both FGF9 and FGF1 could induce the exhibition of the radial morphology in R1cnNestin/R3n and R2cnNestin/R3n, but not R1cnNestin/R2cnNestin, cerebellar glia, which normally would exhibit a stellate astrocytic morphology when being cultured alone. B. Inhibition of ERK1/2, but not AKT, phosphorylation inhibited FGF9 activity to induce glia to adopt the radial morphology. C. FGF induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and AKT in primary culture of cerebellum glia. Western blot with the indicated antibodies demonstrate that FGF1 induces strong activation of both ERK1/2 and AKT, whereas FGF9 induces strong ERK1/2 activation and weak AKT activation. pAKT, phosphorylated AKT; PI3Ki, PI3K inhibitor; pERK1/2, phosphorylated ERK1/2; ERKi, ERK kinase inhibitor. D. Diagrammatic depiction of FGF9 role in cerebellar development. In the normal cerebellum, FGF9 is secreted by granule neurons and acts on FGFR1 or FGFR2 on Bergmann glia (top panel). The FGF9 activity is essential for the maturation and formation of radial fiber scaffolds of Bergmann glia. Fgf9 knockout results in defects in the differentiation of Bergmann glia, the migration of granule neurons, and the alignment and dendritic arborization of Purkinje neurons (bottom panel).

MAP kinase and PI3K/AKT pathways are the two main downstream pathways in the FGF signaling cascade. To determine whether these two pathways were required for FGF9 to induce Bergmann glia differentiation, ex vivo cultures of wildtype glia were treated with the inhibitors for either ERK1/2 or AKT phosphorylations prior to being treated with FGF9. The results demonstrate that inhibition of ERK1/2, but not AKT, phosphorylation abolished FGF9 activity to induce radial morphological changes in the glia (Fig. 7B). Consistently, FGF9 only induced strong ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the cells (Fig. 7C). The results indicate that the MAP kinase pathway is essential for the FGF9-FGFR1/2 signaling axis to control glial differentiation.

DISCUSSION

Biological roles of FGF9 in the formation of the Bergmann fiber scaffold, migration of granule neurons, and maturation of Purkinje cells

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that FGF9 secreted by cerebellar granule neurons played a key role in the differentiation of Bergmann glia, which, in turn, guided the inward migration of granule cells. Detailed analyses with multiple receptor allele ablations in mice and in cell culture assays revealed that FGFR1 and FGFR2 in Bergmann glial cells redundantly mediated the regulatory function of neuron-derived FGF9 during the postnatal cerebellum development (Fig. 7D). Besides the major phenotypes associated with Bergmann glial maturation and granule neuron migration, other minor defects were seen. First, the proliferative window of Fgf9-knockout granule neurons was relatively prolonged, although their ability to express a mature granule cell marker, GABAA α6, appeared not to be disrupted. A previous study has shown that the process of granule cells to stop proliferation and begin migration requires their interaction with Bergmann glial radial fibers (Komuro and Yacubova, 2003). Therefore, it is possible that the prolonged cell division of FGF9-depleted granule neurons may be secondary to the defects in the Bergmann glia. Second, ablation of Fgf9 alleles with either Nestin –Cre or hGFAP-Cre caused similar defects in Purkinje cell soma alignment and dendrite extension. Since hGFAP-Cre was not expressed in Purkinje cells, these results indicate that loss of endogenous Fgf9 was not enough to cause Purkinje cell defects. It has been shown that the Bergmann glia radial fibers also provide a structural support for the directional growth of Purkinje cell dendrites (Lordkipanidze and Dunaevsky, 2005; Yamada et al., 2000). Since the Purkinje cell defects in Fgf9cnNestin mice appeared concurrently with the defect in Bergmann glia fiber formation, the abnormal alignment and dendrite arborization of Purkinje cells in the Fgf9 mutant cerebellum may be caused by the loss of Bergmann glial radial scaffolds.

FGF9 in the fate choice between Bergmann glia and stellate astrocyte

Radial glia are the common precursors for both Bergmann glia and stellate astrocytes (Yamada and Watanabe, 2002). Factors that might influence the decision of radial glia to become either cell type include neuregulin and Notch. The granule cell-derived neuregulin modulates the formation of radial glia scaffold via the erbB receptor on glia cells (Rio et al., 1997; Schmid et al., 2003). Similarly, Purkinje cells expressed DNER, a Notch ligand that can act on the Notch receptor on Bergmann glia to promote their radial glial identity (Eiraku et al., 2005; Gaiano et al., 2000; Lutolf et al., 2002). Our study provides evidence showing that FGF9 may participate in the fate choice between Bergmann and stellate astrocytes. Deleting FGF9 disrupts the growth and expansion of radial fibers of Bergmann glia, and reduces the radial fiber number and the expression of a radial glial marker, BLBP. No increased apoptotic activity had been observed in the Fgf9cnNestin cerebellum (data not shown), suggesting that depletion of FGF9 did not affect cell viability in the cerebellum. The majority of Fgf9cnNestin glia remaining in the ML had a stellate morphology with multipolar and short processes, indicating a possibility that FGF9 may play an instructive role in directing the differentiation of glial progenitors into Bergmann glia instead of astrocytes. This idea is supported by the in vitro findings showing that FGF9 is able to induce a radial morphology from 3% to 68% (Fig. 5A). It has been proposed that the Notch signaling may interact with the FGF pathway (Tanigaki et al., 2001; Yoon et al., 2004) to promote the differentiation of radial glia. Given that the Notch1 expression is not significantly changed in Fgf9cnNestin cerebella (Fig. 5C), it is reasonable to assume that the Notch pathway may act upstream of FGF9.

Granule neuron migration and Bergmann glial differentiation involve multiple FGFRs and FGFs

The primary culture experiments revealed that FGF9, added exogenously or made by co-cultured granule cells, was needed for Bergmann glial to develop a radial glial morphology and express BLBP. Gene ablation models in mice also demonstrate that FGFR1 and 2 redundantly mediate FGF9 signals in cardiomyoblasts (Lavine et al., 2005). In the CNS, Fgfr1 is expressed both in neurons and glial cells (Ohkubo et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2006), whereas Fgfr2 and Fgfr3 are exclusively expressed in glial cells (Miyake et al., 1996; Pringle et al., 2003; Umemori et al., 2004). Our data showed that although single deletion of Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Fgfr3, and Fgfr4 alleles did not cause any detectable defects in cerebellum, double deletion of Fgfr1/Fgfr2, but not that of Fgfr1/Fgfr3 or Fgfr2/Fgfr3, caused similar phenotypes as Fgf9 deletion. In addition, cultured cerebellar glia with Fgfr1/Fgfr3 or Fgfr2/Fgfr3 null alleles can still respond to FGF9, but the Fgfr1/Fgfr2 null glia cannot. Fgfr1/Fgfr2 null glia failed to response to FGF9 with respect to ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Together, the data indicate that the principal function of FGF9 in the cerebellum is primarily mediated redundantly by FGFR1 and FGFR2 via the MAP kinase pathway. Since the double and triple receptor null cerebella exhibited more severe defects than Fgf9 null cerebella, other FGFs are also involved in regulating the cerebellum development. Potential candidates may include FGF14, FGF16, and FGF20, which are expressed in the cerebellum. Consistent with our findings, conditional ablation of the Fgfr2 alleles with EN1-Cre, which is expressed in neuronal progenitor cells two days earlier than Nestin -Cre(Blak et al., 2007), and ablation of Fgfr1 with Nestin–Cre (Zhao et al., 2007) do not cause any morphological defect in the cerebellum. Interestingly, deleting Fgfr1 with EN1-Cre, results in ataxic symptoms and a loss of the cerebellar vermis (Trokovic et al., 2003), suggesting that FGFR1 signals are specifically required for early hindbrain development. Furthermore, reducing FGF signal intensity in embryonic mouse brains affects the development of the vermis (Basson et al., 2008), and double deletion of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 alleles with EN1-Cre results in a loss of the cerebellum (Saarimaki-Vire et al., 2007).

In conclusion, this study establishes FGF9 as an essential molecule that mediates cell-cell communication between the developing cerebellar granule neurons and Bergmann glia. FGF9 is secreted by granule neurons and acts primarily on the FGFR1 and FGFR2 in the Bergmann glia to control the scaffold formation of radial fibers and the own inward migration of granule neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Ornitz, Juha Partanen, and Chuxia Deng for their generosity to share the Fgfr1-floxed, Fgfr2-floxed, Fgfr3-null, and Fgfr4-null mice, and Mary Cole for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by NIH-CA96824 from the NCI and AHA0655077Y from The American Heart Association to F. Wang, and NCI-PHS grant R01 CA113750 from the NCI to R.Y. Tsai.

References

- Adams NC, Tomoda T, Cooper M, Dietz G, Hatten ME. Mice that lack astrotactin have slowed neuronal migration. Development. 2002;129:965–72. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson MA, Echevarria D, Petersen Ahn C, Sudarov A, Joyner AL, Mason IJ, Martinez S, Martin GR. Specific regions within the embryonic midbrain and cerebellum require different levels of FGF signaling during development. Development. 2008;135:889–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.011569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaess S, Corrales JD, Joyner AL. Sonic hedgehog regulates Gli activator and repressor functions with spatial and temporal precision in the mid/hindbrain region. Development. 2006;133:1799–809. doi: 10.1242/dev.02339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blak AA, Naserke T, Saarimaki-Vire J, Peltopuro P, Giraldo-Velasquez M, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Prakash N, Sendtner M, Partanen J, Wurst W. Fgfr2 and Fgfr3 are not required for patterning and maintenance of the midbrain and anterior hindbrain. Dev Biol. 2007;303:231–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanas-Sacre G, Rogister B, Moonen G, Leprince P. Radial glia phenotype: origin, regulation, and transdifferentiation. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:357–63. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<357::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YT, Collins LL, Uno H, Chang C. Deficits in motor coordination with aberrant cerebellar development in mice lacking testicular orphan nuclear receptor 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2722–32. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2722-2732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi CL, Martinez S, Wurst W, Martin GR. The isthmic organizer signal FGF8 is required for cell survival in the prospective midbrain and cerebellum. Development. 2003;130:2633–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.00487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinaroglu A, Ozmen Y, Ozdemir A, Ozcan F, Ergorul C, Cayirlioglu P, Hicks D, Bugra K. Expression and possible function of fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9) and its cognate receptors FGFR2 and FGFR3 in postnatal and adult retina. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:329–39. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RI, Chandross KJ. Fibroblast growth factor-9 modulates the expression of myelin related proteins and multiple fibroblast growth factor receptors in developing oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:273–87. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000801)61:3<273::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin JS, Green RP, Schmahl J, Capel B, Ornitz DM. Male-to-female sex reversal in mice lacking fibroblast growth factor 9. Cell. 2001;104:875–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Cell. 1996;84:911–21. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M, Tohgo A, Ono K, Kaneko M, Fujishima K, Hirano T, Kengaku M. DNER acts as a neuron-specific Notch ligand during Bergmann glial development. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:873–80. doi: 10.1038/nn1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiano N, Nye JS, Fishell G. Radial glial identity is promoted by Notch1 signaling in the murine forebrain. Neuron. 2000;26:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces A, Nishimune H, Philippe JM, Pettmann B, de Lapeyriere O. FGF9: a motoneuron survival factor expressed by medial thoracic and sacral motoneurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;60:1–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000401)60:1<1::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldowitz D, Hamre K. The cells and molecules that make a cerebellum. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:375–82. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatten ME. Neuronal regulation of astroglial morphology and proliferation in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:384–96. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husmann K, Faissner A, Schachner M. Tenascin promotes cerebellar granule cell migration and neurite outgrowth by different domains in the fibronectin type III repeats. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1475–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T, Iwasaki T, Nakamura S, Kurokawa T, Ikeda K, Mizusawa H. Self-secretion of fibroblast growth factor-9 supports basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in an autocrine/paracrine manner. Brain Res. 2000;876:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro H, Yacubova E. Recent advances in cerebellar granule cell migration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1084–98. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2248-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine KJ, Yu K, White AC, Zhang X, Smith C, Partanen J, Ornitz DM. Endocardial and epicardial derived FGF signals regulate myocardial proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Dev Cell. 2005;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Liu G, Wang F. Generation of an Fgf9 conditional null allele. Genesis. 2006;44:150–4. doi: 10.1002/gene.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Liu G, Zhang Y, Hu YP, Yu K, Lin C, McKeehan K, Xuan JW, Ornitz DM, Shen MM, Greenberg N, McKeehan WL, Wang F. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 tyrosine kinase is required for prostatic morphogenesis and the acquisition of strict androgen dependency for adult tissue homeostasis. Development. 2007;134:723–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.02765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lordkipanidze T, Dunaevsky A. Purkinje cell dendrites grow in alignment with Bergmann glia. Glia. 2005;51:229–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutolf S, Radtke F, Aguet M, Suter U, Taylor V. Notch1 is required for neuronal and glial differentiation in the cerebellum. Development. 2002;129:373–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeehan WL, Wang F, Kan M. The heparan sulfate-fibroblast growth factor family: diversity of structure and function. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;59:135–76. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor JR, Merlo D, Jones A, Wisden W, Randall AD. Mouse cerebellar granule cell differentiation: electrical activity regulates the GABAA receptor alpha 6 subunit gene. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2822–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Hattori Y, Ohta M, Itoh N. Rat oligodendrocytes and astrocytes preferentially express fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 and -3 mRNAs. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:534–41. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960901)45:5<534::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Todo T, Motoi Y, Haga S, Aizawa T, Ueki A, Ikeda K. Glial expression of fibroblast growth factor-9 in rat central nervous system. Glia. 1999;28:53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naruo K, Seko C, Kuroshima K, Matsutani E, Sasada R, Kondo T, Kurokawa T. Novel secretory heparin-binding factors from human glioma cells (glia-activating factors) involved in glial cell growth. Purification and biological properties. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2857–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea KS, Rheinheimer JS, Dixit VM. Deposition and role of thrombospondin in the histogenesis of the cerebellar cortex. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1275–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo Y, Uchida AO, Shin D, Partanen J, Vaccarino FM. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is required for the proliferation of hippocampal progenitor cells and for hippocampal growth in mouse. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6057–69. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1140-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle NP, Yu WP, Howell M, Colvin JS, Ornitz DM, Richardson WD. Fgfr3 expression by astrocytes and their precursors: evidence that astrocytes and oligodendrocytes originate in distinct neuroepithelial domains. Development. 2003;130:93–102. doi: 10.1242/dev.00184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio C, Rieff HI, Qi P, Khurana TS, Corfas G. Neuregulin and erbB receptors play a critical role in neuronal migration. Neuron. 1997;19:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarimaki-Vire J, Peltopuro P, Lahti L, Naserke T, Blak AA, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Yu K, Ornitz DM, Wurst W, Partanen J. Fibroblast growth factor receptors cooperate to regulate neural progenitor properties in the developing midbrain and hindbrain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8581–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0192-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Joyner AL, Nakamura H. How does Fgf signaling from the isthmic organizer induce midbrain and cerebellum development? Dev Growth Differ. 2004;46:487–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169x.2004.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid RS, McGrath B, Berechid BE, Boyles B, Marchionni M, Sestan N, Anton ES. Neuregulin 1-erbB2 signaling is required for the establishment of radial glia and their transformation into astrocytes in cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630496100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Ohkubo Y, Maragnoli ME, Rasin MR, Schwartz ML, Sestan N, Vaccarino FM. Midline radial glia translocation and corpus callosum formation require FGF signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:787–97. doi: 10.1038/nn1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo C. Cellular and genetic regulation of the development of the cerebellar system. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;72:295–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- darov A, Joyner AL. Cerebellum morphogenesis: the foliation pattern is orchestrated by multi-cellular anchoring centers. Neural Develop. 2007;2:26. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagashira S, Ozaki K, Ohta M, Itoh N. Localization of fibroblast growth factor-9 mRNA in the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;30:233–41. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00009-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanigaki K, Nogaki F, Takahashi J, Tashiro K, Kurooka H, Honjo T. Notch1 and Notch3 instructively restrict bFGF-responsive multipotent neural progenitor cells to an astroglial fate. Neuron. 2001;29:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todo T, Kondo T, Kirino T, Asai A, Adams EF, Nakamura S, Ikeda K, Kurokawa T. Expression and growth stimulatory effect of fibroblast growth factor 9 in human brain tumors. Neurosurgery. 1998a;43:337–46. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199808000-00098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todo T, Kondo T, Nakamura S, Kirino T, Kurokawa T, Ikeda K. Neuronal localization of fibroblast growth factor-9 immunoreactivity in human and rat brain. Brain Res. 1998b;783:179–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trokovic R, Trokovic N, Hernesniemi S, Pirvola U, Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Rossant J, McMahon AP, Wurst W, Partanen J. FGFR1 is independently required in both developing mid- and hindbrain for sustained response to isthmic signals. Embo J. 2003;22:1811–23. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemori H, Linhoff MW, Ornitz DM, Sanes JR. FGF22 and its close relatives are presynaptic organizing molecules in the mammalian brain. Cell. 2004;118:257–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Bardgett ME, Wong M, Wozniak DF, Lou J, McNeil BD, Chen C, Nardi A, Reid DC, Yamada K, Ornitz DM. Ataxia and paroxysmal dyskinesia in mice lacking axonally transported FGF14. Neuron. 2002;35:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang VY, Zoghbi HY. Genetic regulation of cerebellar development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:484–91. doi: 10.1038/35081558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Xu X, Ohyama K, Deng CX. FGFR-3 and FGFR-4 function cooperatively to direct alveogenesis in the murine lung. Development. 1998;125:3615–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M, Krautler N, Mantei N, Suter U, Taylor V. Jagged1 ablation results in cerebellar granule cell migration defects and depletion of Bergmann glia. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:70–80. doi: 10.1159/000090754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Liu Z, Ornitz DM. Temporal and spatial gradients of Fgf8 and Fgf17 regulate proliferation and differentiation of midline cerebellar structures. Development. 2000;127:1833–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.9.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Fukaya M, Shibata T, Kurihara H, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Watanabe M. Dynamic transformation of Bergmann glial fibers proceeds in correlation with dendritic outgrowth and synapse formation of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:106–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Watanabe M. Cytodifferentiation of Bergmann glia and its relationship with Purkinje cells. Anat Sci Int. 2002;77:94–108. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-7722.2002.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K, Nery S, Rutlin ML, Radtke F, Fishell G, Gaiano N. Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling promotes radial glial identity and interacts with Notch1 signaling in telencephalic progenitors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9497–506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0993-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Xu J, Liu Z, Sosic D, Shao J, Olson EN, Towler DA, Ornitz DM. Conditional inactivation of FGF receptor 2 reveals an essential role for FGF signaling in the regulation of osteoblast function and bone growth. Development. 2003;130:3063–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Ibrahimi OA, Olsen SK, Umemori H, Mohammadi M, Ornitz DM. Receptor specificity of the fibroblast growth factor family. The complete mammalian FGF family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15694–700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601252200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Li D, Shimazu K, Zhou YX, Lu B, Deng CX. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor-1 Is Required for Long-Term Potentiation, Memory Consolidation, and Neurogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo L, Theis M, Alvarez-Maya I, Brenner M, Willecke K, Messing A. hGFAP-cre transgenic mice for manipulation of glial and neuronal function in vivo. Genesis. 2001;31:85–94. doi: 10.1002/gene.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.