Abstract

Human tail is a curiosity, a cosmetic stigma and presents as an appendage in the lumbosacral region. Six patients of tail in the lumbosacral region are presented here to discuss the spectrum of presentation of human tails. The embryology, pathology and treatment of this entity are discussed along with a brief review of the literature.

KEY WORDS: Human tail, lipomyelomeningocele, sacrococcygeal teratoma, spina bifida

INTRODUCTION

Human tails are a rare entity. The birth of a baby with a tail can cause tremendous psychological disturbance to the parents. They are usually classified as true and pseudo tails.[1] Tails are usually associated with occult spinal dysraphism.[2] Isolated case reports of various types of human tails have been described in the literature.[3] We are presenting our experience of six cases of tails in infants.

CASE REPORT

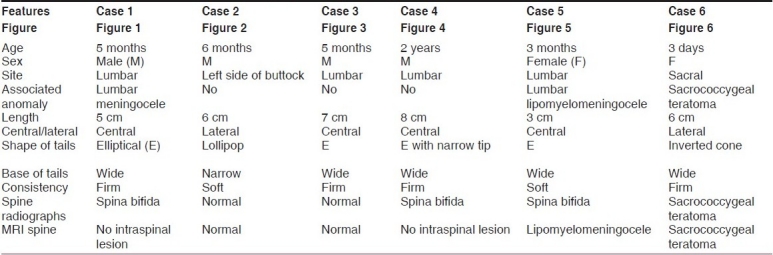

The age range of patients varied from 3 days to 2 years. The male to female ratio was 2:1. The family history was not significant in any of the patients. The antenatal history of the mothers was normal. There was no movement or contraction of tails in our patients. The main features and imaging findings of six patients have been summarised in Table 1. The plain radiographs showed spina bifida in three patients at L 5 and S 1.

Table 1.

Summary of main features and imaging findings of all patients

Other than patient number 5 (lumbar lipomeningomyelocele), all other patients underwent surgical excision. An elliptical incision was made encircling the base of the appendage. No connection with the spine was seen. The patient with meningocele had formal repair of the meningocele. A complete excision of the sacrococcygeal teratoma was done. The postoperative result was excellent. The parents of patient number 5 refused to give consent for the operation and the patient was lost to follow-up.

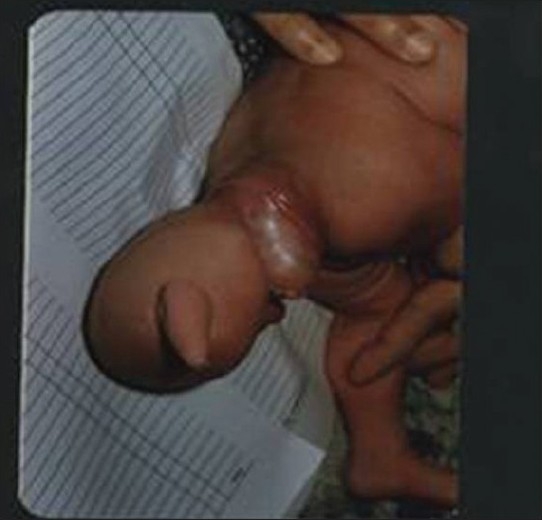

On histopathological examination, the specimen of sacrococcygeal teratoma showed mature tissues that included bones, cartilage, fat and neural tissues, whereas other tails showed mature adipose tissue, blood vessels and nerves.

DISCUSSION

A “vestigial tail” describes a remnant of a structure found in embryonic life or in ancestral forms.[4] During the 5th to 6th week of intrauterine life, the human embryo has a tail with 10–12 vertebrae. By 8 weeks, the human tail disappears. The persistent tail probably arises from the distal nonvertebrate remnant of the embryonic tail.[5] True human tail arises from the most distal remnant of the embryonic tail. It contains adipose tissue, connective tissue, central bundles of striated muscle, blood vessels and nerves and is covered by skin. Bone, cartilage, notochord and spinal cord are lacking. It can move and contract and occurs twice as often in males as in females. None of our patients showed any movement of the tail. Unlike the tail of other vertebrates, human tails do not contain vertebral structures. Only one case has been reported with vertebra in human tail.[6] A true tail is easily removed surgically, without residual effects. It is rarely familial.[1] Pseudo tails have got superficial resemblance to true tails. They are anomalous prolongation of the coccygeal vertebrae. The additional lesions found with pseudo tails are lipomas, teratomas, chondromegaly and gliomas, and there may be elongated parasitic fetus.[1] Human tail usually occurs in the lumbosacral region, but it has also been reported in the cervical region.[7] Teratoma in the human tail has also been reported.[8] In a review series of 48 skin-covered lumbosacral masses, 25% had lumbosacral and sacrococcygeal teratomas.[9] In our series, we had only one patient with tail in sacrococcygeal teratoma.

The preoperative assessment includes a complete clinical examination including neurology, plain radiographs of the spine and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. An occult spinal lesion has been reported in around 50% of the cases.[2] In another review by Lu, 20% of the cases are associated with either meningocele or spina bifida occulta.[10] Other than the patient of lipomyelomeningocele, none of our patients showed intraspinal lesion.

Figure 1.

Tail in the midline of lumbar region

Figure 2.

Tail in the left side of the buttock, away from the midline

Figure 3.

Tail in the midline of lumbar region

Figure 4.

Tail in the midline of lumbar region

Figure 5.

Tail in the midline of lumbar region (lipomyelomeningocele)

Figure 6.

Sacrococcygeal teratoma with tail, away from the midline

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dao AH, Netsky MG. Human tails and pseudo tails. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:449–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh DK, Kumar B, Sinha VD, Bagaria HR. The human tail: A rare lesion with a occult spinal dysraphism- A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:E41–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakrabortty S, Oi S, Yoshida Y, Yamada H, Yamaguchi M, Tamaki N, et al. Myelomeningocele and thick filum terminale with tethered cord appearing as a human tail. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:966–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.6.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belzberg AJ, Myles ST, Trevner CL. The human tail and spinal dysraphism. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1243–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90343-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmer EZ, Bronshtein M. Early sonographic findings suggestive of human fetal tail. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:360–2. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199604)16:4<360::AID-PD857>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabra NS, Srinivasan G, Udani RH. True tail in a neonate. Indian Pediatr. 1999;36:712–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohindra S. The ‘human tail’ causing tethered cervical cord. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:583–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SH, Huh JS, Cho KH, Shin YS, Kim SH, Ahn YH, et al. Teratoma in human tail lipoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:158–61. doi: 10.1159/000085876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mc Lone DG, Naidich TP. Terminal myelocystocele. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu FL, Wang PJ, Teng RJ, Yau KI. The human tail. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;19:230–3. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]