Abstract

Herbs have been used in medicines and cosmetics from centuries. Their potential to treat different skin diseases, to adorn and improve the skin appearance is well-known. As ultraviolet (UV) radiation can cause sunburns, wrinkles, lower immunity against infections, premature aging, and cancer, there is permanent need for protection from UV radiation and prevention from their side effects. Herbs and herbal preparations have a high potential due to their antioxidant activity, primarily. Antioxidants such as vitamins (vitamin C, vitamin E), flavonoids, and phenolic acids play the main role in fighting against free radical species that are the main cause of numerous negative skin changes. Although isolated plant compounds have a high potential in protection of the skin, whole herbs extracts showed better potential due to their complex composition. Many studies showed that green and black tea (polyphenols) ameliorate adverse skin reactions following UV exposure. The gel from aloe is believed to stimulate skin and assist in new cell growth. Spectrophotometer testing indicates that as a concentrated extract of Krameria triandra it absorbs 25 to 30% of the amount of UV radiation typically absorbed by octyl methoxycinnamate. Sesame oil resists 30% of UV rays, while coconut, peanut, olive, and cottonseed oils block out about 20%. A “sclerojuglonic” compound which is forming from naphthoquinone and keratin is the reaction product that provides UV protection. Traditional use of plant in medication or beautification is the basis for researches and making new trends in cosmetics. This review covers all essential aspects of potential of herbs as radioprotective agents and its future prospects.

Keywords: Antioxidants, cosmetics, plant extract, sunblocks, Ultra violet radiation

INTRODUCTION

Sunscreen products are very popular on markets last years. But, the reason for their production is different now. In the beginning, people wanted to get beautiful sun tan easily and fast, without the risk to get burns. Nowadays, it is necessary for all people to use sunscreen products because of protection against ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This review covers all essential aspects of potential of herbs as radioprotective agents and its future prospects.

Ultraviolet radiation

Electromagnetic radiation is broadly divided into infrared radiation (IR), visible light (VIS), and UV radiation. Heat is part of IR radiation, which is not visible to the human eye. VIS is the wavelength range of general illumination. UV radiation is divided into three distinct bands in order of decreasing wavelength and increasing energy: UVA (320-400 nm), UVB (290-320 nm), and UVC (200-290 nm). Different wavelengths and energy associated with UV subdivision correspond to distinctly different effects on living tissue.[1]

Ultraviolet C radiation

UVC, although it possesses the highest energy and has the greatest potential for biological damage, is effectively filtered by the ozone layer and is therefore not considered to be a factor in solar exposure of human beings[1] and is not of biological relevance.[2]

Ultraviolet B radiation

The amount of solar UVB and UVA reaching the earth's surface is affected by latitude, altitude, season, time of the day, cloudiness, and ozone layer. The highest irradiance is at the equator and higher elevations. On the earth's surface, the ratio of UVA to UVB is 20 : 1. UV radiation is strongest between 10 am and 4 pm.[3] During a summer day, the UV spectrum that reaches the earth's surface consists of 3.5% UVB and 96.5% UVA. UVB is primarily associated with erythema and sunburn. It can cause immunosuppression and photocarcinogenesis.[1]

Ultraviolet A radiation

Because UVA is of longer wavelength compared with UVB, it is less affected by altitude or atmospheric conditions. UVA, compared with UVB, can penetrate deeper through the skin,[1,3] and is not filtered by window glass. It has been estimated that approximately 50% of exposure to UVA occurs in the shade.[3,4]

In contrast to UVB, it is more efficient in inducing immediate and delayed pigment darkening and delayed tanning than in producing erythema. UVA is known to have significant adverse effects including immunosuppression, photoaging, ocular damage, and skin cancer.[5–9]

UVA rays are beneficial since they increase vitamin D3 production through the irradiation of 7-dihydrocholesterol. They intensify the darkening of preformed melanin pigment favoring tanning. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that these rays are responsible for photosensitivity which result in several types of allergic reactions and actinic lesions.[10]

Damaging effects of ultraviolet radiation

Acute response of human skin to UVB irradiation includes erythema, edema, and pigment darkening followed by delayed tanning, thickening of the epidermis and dermis, and synthesis of vitamin D; chronic UVB effects are photoaging, immunosuppression, and photocarcinogenesis.[3,11] UVB-induced erythema occurs approximately 4 hours after exposure, peaks around 8 to 24 hours, and fades over a day or so; in fair-skinned and older individuals, UVB erythema may be persistent, sometimes lasting for weeks.[3,12] The effectiveness of UV to induce erythema declines rapidly with longer wavelength; to produce the same erythemal response, approximately 1 000 times more UVA dose is needed compared with UVB.[2,3,13,14] The time courses for UVA-induced erythema and tanning are biphasic. Erythema is often evidenced immediately at the end of the irradiation period,[3,15] it fades in several hours, followed by a delayed erythema starting at 6 hours and reaching its peak at 24 hours.[3,15–18] The action spectrum for UV-induced tanning and erythema are almost identical; however, UVA is more efficient in inducing tanning, whereas UVB is more efficient in inducing erythema.[3,19]

Skin care products for UV protection should be used to reduce harmful effects of UV radiation and/or suppress them totally. Therefore, UV protection becomes a major function of more types of cosmetic formulations.

HISTORY OF COSMETICS

The use of natural or synthetic cosmetics to treat the appearance of the face and condition of the skin is common among many cultures. The word “cosmetics” arises from a Greek word “kosmeticos” which means to adorn. Since that time, any material used for beautification or improvement of appearance is known as cosmetics. The urge to adorn one's own body and look beautiful has been an urge in the human race since the tribal days. The practice of adornment or improvement of appearance continued unabated across the centuries. Various kinds of natural materials were used for that purpose. In modern days, cosmetics are the rage and are considered to be essential commodities of life.[20] This made the scientist carry out research in cosmetics and as a result, more and more products are being developed and marketed. Body and beauty care product are likely to surpass the consumption of drugs in future. A large segment of the world population is showing greater inclination toward natural cosmetics which seems to be the future hope.[21]

Cosmetics or dermocosmetic preparations are used for skin care, cleaning, and protection. They have contact with external parts of human body (epidermis, hair, nails, lips, and external sexual organs), or with teeth and mouth mucose. They clean, perfume, change look and/or make correction of body smells and/or keep them in appropriate condition. Cosmetics involve skin care products for UV protection.[22]

Competition among manufacturers of cosmetics is intense. Because of that, companies formulate with added value ingredients to create products that can claim specific benefits—wrinkles decreasing, longwearing, moisturizing, transfer resistant, oil control. Today, another way of increasing the value of these products to consumers is delivering sun protection in foundations and lipsticks. This provides broad-spectrum protection against the harmful effects of UV light. There are a lot of government regulations for sunscreen actives. In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration regulate the sales of color cosmetics containing sunscreens under cosmetics and drug legislation. In Europe, sunscreen products are regulated like cosmetics. COLIPA, the trade association for the EEC, works with regulatory agencies in individual countries to establish legislation. France and Italy, unlike other EEC countries, require labeling of active ingredients and concentration present in finished products.[23]

Sunscreen products

There are a lot of different types of sunscreen products (oils, sticks, gels, creams, lotions) which can be found on the world's market. All of them must have sunscreens that provide adequate protection from harmful UV rays (UVA and UVB).

There are two general types of sunscreens—chemical and physical. A chemical sunscreen absorbs the UV rays, while the physical sunscreen reflects the harmful rays away from the skin like a temporary coat of armor.[24]

Physical sunblocks

There are two types of physical sunblocks that are mostly used: Zinc oxide and titanium dioxide. Both provide broad-spectrum UVA and UVB protection. They are gentle enough for everyday use, especially for individuals with sensitive skin and for children, because they rarely cause skin irritation. But, because of scattering effect, they often causes so called “whitening” phenomenon when they are applied on the skin, which seriously affects the aesthetics and the efficacy of sunscreen products.[23–25]

Chemical sunblocks

Most chemicals only block narrow region of the UV spectrum. Therefore, most chemical sunblocks are composed of several chemicals with each one blocking a different region of UV light. Mostly, chemicals used in sunblocks are active in UVB region. Only a few chemicals block the UVA region. The best sunblock is the sunblock that combine both chemical and physical active ingredients. Dermatologists routinely recommend sunblocks that contain either a physical blocking agent or avobenzone (Parsol®1789) in combination with other chemicals. However, in the USA, combinations of avobenzone and physical sunscreens are not permitted. Avobenzone has been reported to be unstable when contained in formulations with physical sunscreens. Surface coating of pigment has sometimes been shown to increase its stability.[26]

Whitening is unacceptable in beach and skin care products with sun protection factor (SPF). It is difficult to create elegant formulations useful to protect against harmful UVA/B rays. Now, broad-spectrum protection in foundations is achievable using titanium dioxide with greater scattering power and iron oxides.[23] Many of the organic chemicals commonly used in sunscreen products have not been established safe for long-term human use. For example, titanium dioxide- and zinc oxide-based sunscreens are being promoted on the basis that they may be less harmful than organic sunscreen absorbers. But, the use of microfine titanium dioxide as a sunscreen product also has no long-term safety data.[27] Today, manufacturers use a lot of different natural components for skin protection from UV radiation. These products contain a high level of natural UV absorbers such as squalane, peptides, and nucleotides that have been protecting mammalian skin for over 100 million years.[28]

HERBAL COSMETICS

In a quest to find effective topical photoprotective agents, plant-derived products have been researched for their antioxidant activity, so the use of natural antioxidants in commercial skin care products is increasing. Today, we look at the chemical composition of herbal remedies to ascertain what it is chemically and pharmacologically that might be responsible for these effects. Effective botanical antioxidant compounds are widely used in traditional medicine and include tocopherols, flavonoids, phenolic acids, nitrogen containing compounds (indoles, alkaloids, amines, and amino acids), and monoterpenes. As the topical supplementation of antioxidants has been shown to affect the antioxidant network in the skin, applying aromatherapy formulations that are rich in antioxidants offers interesting avenues for future research.[29] The next step has been to look at other cultural remedies and to dissect the ethnopharmacy of countries around the world and to use our knowledge to assign chemicals that might be responsible for the skin benefits. Many new active molecules have been discovered and there are many more to be discovered.[30]

Natural sun blockers

The skin's natural sun blockers are proteins (the peptide bonds), absorbing lipids, and nucleotides. The high concentration of plant peptides protects the peptide bonds of the skin proteins. The high level of squalane (from olive oil) in some products protects the skin's sensitive lipids. Squalene is the skin's most important protective lipid. Allantoin is a nucleotide that naturally occurs in the body and absorbs the spectrum of UV radiation which damages the cell's fragile DNA. Allantoin is an extract of the comfrey plant and is used for its healing, soothing, and anti-irritating properties. This extract can be found in antiacne products, sun care products, and clarifying lotions because of its ability to help heal minor wounds and promote healthy skin.[31] Some clinical studies confirm that allantoin enhance skin repair.[28]

Natural sources of antioxidants

The main destroying factors for skin are oxygenated molecules which are often call “free radicals.” To stimulate the skin to repair and build itself naturally, we need an arsenal of potent ingredients. The “antioxidant power” of a food is an expression of its capability both to defend the human organism from the action of the free radicals and to prevent degenerative disorders deriving from persistent oxidative stress.[32] Plants like olive trees have their own built-in protection against the oxidative damage of the sun, and these built-in protectors function as cell protectors in our own body. The very pigments that make blueberries blue and raspberries red protect those berries from oxidative damage.[33]

Anthocyanins

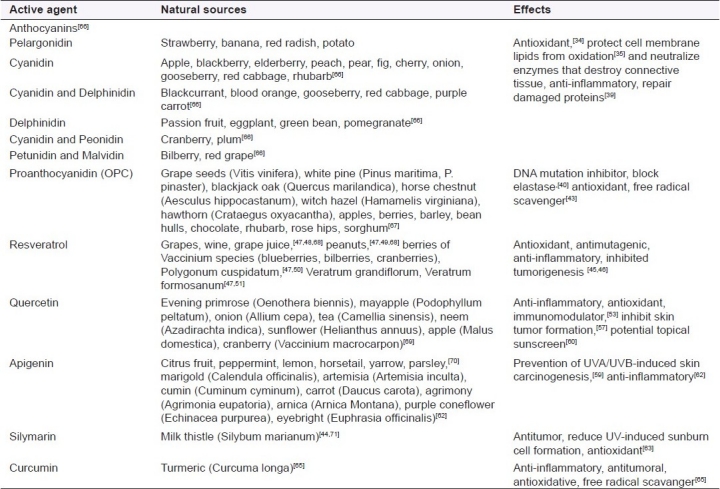

Anthocyanidins and their derivatives, many found in common foods [Table 1], protect against a variety of oxidants through a number of mechanisms. Cyanidins, found in most fruit sources of anthocyanins, have been found to “function as a potent antioxidant in vivo” in recent Japanese animal studies.[34] In other animal studies, cyanidins protected cell membrane lipids from oxidation by a variety of harmful substances.[35] Additional animal studies confirm that cyanidin is four times more powerful an antioxidant than vitamin E.[36] The anthocyanin pelargonidin protects the amino acid tyrosine from the highly reactive oxidant peroxynitrite.[37] Eggplant contains a derivative of the anthocyanidin delphinidin called nasunin, which interferes with the dangerous hydroxyl radical-generating system—a major source of oxidants in the body.[38]

Table 1.

Natural substances for skin protection

They neutralize enzymes that destroy connective tissue. Their antioxidant capacity prevents oxidants from damaging connective tissue. Finally, they repair damaged proteins in the blood-vessel walls.[39]

Proanthocyanidin

Proanthocyanidin (OPC) works as a DNA mutation inhibitor. Also, OPC block elastase, maintaining the integrity of elastin in the skin and act synergistically with both vitamin C and E, protect and replenish them.[40] OPC in cream form has been researched and demonstrated to be effective against the dangerous effects of the sun (UV rays). When OPC cream is applied to the skin before exposure to the sun, less burning of the skin occurs.[41] In one study, grape seed [Table 1] OPCs exerted a solo antioxidant effect at a level of potency on a par with vitamin E-protecting different polyunsaturated fatty acids from UV light-induced lipid peroxidation. In this same study, the grape OPCs synergistically interacted with vitamin E, recycling the inactivated form of the vitamin into the active form and thus acting as a virtual vitamin E extender.[42]

Grape seed proanthocyanidins (GSP) are potent antioxidants and free radical scavengers. GSP inhibited skin tumor formation and decreased the size of skin tumors in hairless mice exposed to carcinogenic UV radiation. Exposure to UV radiation can suppress the immune system, but GSP prevented this suppression in mice fed a diet containing GSP. Treatment of cells with GSP increased tumor cell death in a model used to study tumor promotion in skin cells.[43]

Resveratrol

Resveratrol belongs to a class of polyphenolic compounds called stilbenes. Resveratrol is a fat-soluble compound that occurs in a trans and a cis configuration. Resveratrol is a naturally occurring polyphenolic phytoalexin.[44] Resveratrol was found to act as an antioxidant and antimutagen; it mediated anti-inflammatory effects; and it induced human promyelocytic leukemia cell differentiation. In addition, it inhibited the development of preneoplastic lesions in carcinogen-treated mouse mammary glands in culture and inhibited tumorigenesis in a mouse skin cancer model.[45] Topical application of resveratrol SKH-1 hairless mice prior to UVB irradiation resulted in a significant decrease in UVB-generation of H2O2 as well as infiltration of leukocytes and inhibition of skin edema. Long-term studies have demonstrated that topical application with resveratrol (both pre- and post-treatment) results in inhibition of UVB-induced tumor incidence and delay in the onset of skin tumorigenesis.[46]

Foods known to contain resveratrol are limited to grapes, wine, grape juice, cranberries, cranberry juice,[47,48] peanuts, and peanut products[47,49] [Table 1]. Vastano et al. have shown that the roots of the weed Polygonum cuspidatum constitute one of the richest sources of resveratrol (2 960–3 770 ppm).[47,50] High levels of resveratrol have also been detected in leaves of Veratrum grandiflorum and in roots and rhizomes of Veratrum formosanum. These last three plants have been extensively used in Japanese and Chinese folk medicine for their health properties (laxative, anti-arteriosclerosis, anticancer).[47,51]

Quercetin

The most common flavonol in the diet is quercetin.[52] Quercetin has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and act as a immunomodulator.[53] A diet rich in quercetin has been reported to inhibit the development of carcinogen-induced rat mammary cancer,[54] colonic neoplasia,[55] oral carcinogenesis,[56] and skin tumor formation in three models of skin carcinogenesis in mice when administered by topical application.[57] Quercetin may account for the beneficial effects of dietary fruits and vegetables [Table 1] on mutagens and carcinogens, including metals.[58] It is present in various common fruit and vegetables, beverages, and herbs.[59] The highest concentrations are found in onion.[52]

Quercetin and rutin were tested as potential topical sunscreen factors in human beings and found to provide protection in the UVA and UVB range.[60]

Apigenin

Apigenin is a widely distributed plant flavonoid occurring in herbs, fruit, vegetables, and beverages [Table 1]. Apigenin was found to be effective in the prevention of UVA/UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis in SKH-1 mice.[59] Apigenin did not inhibit nuclear translocation of NF-κB, but did inhibit reporter gene expression driven by NF-κB.[61] Apigenin is also found in marigold (Calendula officinalis), where it was shown, using the mouse ear test, that the flavonoids were responsible for the activity and, of these, apigenin was more active than indomethacin in the test. Artemisia (Artemisia inculta) and Cuminum cyminum or cumin also contain apigenin and luteolin and their derivatives in addition to plants like carrot (Daucus carota), agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria), arnica (Arnica montana), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), and eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis)—all of which have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity when used under the right conditions.[62]

Silymarin

Silymarin is a flavonoid compound found in the seeds of milk thistle (Silybum marianum)[63] [Table 1]. Silymarin consists of the following three phytochemicals: silybin, silidianin, and silicristin. Silybin is the most active phytochemical.[44] Topical silymarin has been shown to have a remarkable antitumor effect. The number of tumors induced in the skin of hairless mice by UVB light was reduced by 92%. Silymarin reduced UV-induced sunburn cell formation and apoptosis. The result was not related to a sunscreen effect and an antioxidant mechanism may be responsible.[62] Silymarin treatment prevents UVB-induced immune suppression and oxidative stress in vivo.[64]

Curcumin

Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) is a yellow odorless pigment isolated from the rhizome of turmeric (Curcuma longa) [Table 1]. Curcumin possesses anti-inflammatory,[44,65] antitumoral, and antioxidant properties. It has been found that topical application of curcumin in epidermis of CD-1 mice significantly inhibited UVA-induced ornithine decarboxylase ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) activity. The inhibitory effects of curcumin were attributed to its ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species reactive oxygen species (ROS). Curcumin can prevent UV irradiation-induced apoptotic changes in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells.[65]

Table 1 gives more details on natural substances used for skin protection.

Vitamin E

The antioxidant vitamin E (α-tocopherol) may protect both animal and plant cell membranes from light-induced damage.[72] Topical application of these antioxidants to the skin has been shown to reduce acute and chronic photodamage. Topically applied, only the natural forms of vitamin E—alpha-tocopherol and tocotrienol—effectively reduce skin roughness, the length of facial lines, and the depth of wrinkles.[73] Topically applied vitamin E increases hydratation of the stratum corneum and increases its water-binding capacity. Alpha-tocopherol reduces the harmful collagen-destroying enzyme collagenase, which unfortunately increases in aging skin.[74] Vitamin E is a free radical scavenger and an emollient too.[75]

Triticum vulgare (wheat germ) oil is particularly rich in vitamin E and offers excellent antioxidant promise in topical antiaging formulations. Also, it nourishes and prevents loss of moisture from the skin.[76] Extra virgin Corylus avellana (hazelnut) oil has good levels of tocopherols, as do Helianthus annuus (sunflower) and Sesamum indicum (sesame) oils.[29]

Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin) seed oil deserves greater recognition. With a lipid profile containing high levels of linoleic acid (43 – 53%), it contains two classes of antioxidant compounds: Tocopherols and phenolics, which account for 59% of the antioxidant effects. It is especially valued in the healing folklore of Eastern and Central Europe and the Middle East for its nutritious benefits and is used both topically and orally for a range of medical conditions. Due to the strong, rich aroma, it is only used in small proportions in topical formulations.[29]

Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C)

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) is the body's most important intracellular and extracellular aqueous-phase antioxidant. Vitamin C provides many benefits to the skin—most significantly, increased synthesis of collagen and photoprotection. Photoprotection is enhanced by the anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin C. Photoprotection over many months allows the skin to correct previous photodamage, the synthesis of collagen and inhibition of MMP-1 was proven to decrease wrinkles, and the inhibition of tyrosinase and anti-inflammatory activity result in depigmenting solar lentigines.[75]

Vitamin C is found in active form and substantial quantities in Rosehip seed extract or oil.[59]

Carotenoids

Dietary carotenoids from a healthy unsupplemented diet accumulate in the skin and their level significantly correlates with sun protection. Eating large quantities of fish oil appears to provide a sun protective effect, in some cases up to an SPF of 5, and may reduce the UV-induced inflammatory response by a lowered prostaglandin E2 levels (a mediator in the arachidonic acid cascade for inflammation). In human fibroblasts, lycopene, β-carotene, and lutein were all capable of significantly reducing lipid peroxidation caused by UVB. One clinical study reported significant improvements in skin thickness, density, roughness, and scaling after 12-week oral supplementation with lycopene, lutein, β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and selenium. Another human trial with oral administration of lycopene β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and selenium reported decreased UV-induced erythema, lipid peroxidation, and sunburn cell formation.[75]

Oil extracted from the fruits and pulp of Hippophae rhamnoides (sea buckthorn) has long been used in skin care in Turkey, China, and Russia and represents interesting possibilities for future research in antiaging formulations.[29] It contains high levels of linoleic (30 – 40%) and α–linolenic (23 – 36%) acids.[29]

WHOLE HERBAL EXTRACTS IN USE

Whole herbal extracts consist of numerous compounds that together provide better effects on the skin. One herbal extract may show antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, emollient, melanin-inhibiting, antimutagenic, antiaging properties, etc.

Green and black tea

Most people have tea in their kitchen. Tea (Camellia sinensis) is commonly used as a home remedy for sunburn. The Chinese recommend applying cooled black tea to the skin to soothe sunburn. One says that the tannic acid and theobromine in tea help remove heat from sunburns. Other compounds in tea called catechins help prevent and repair skin damage and may even help prevent chemical- and radiation- induced skin cancers.[77]

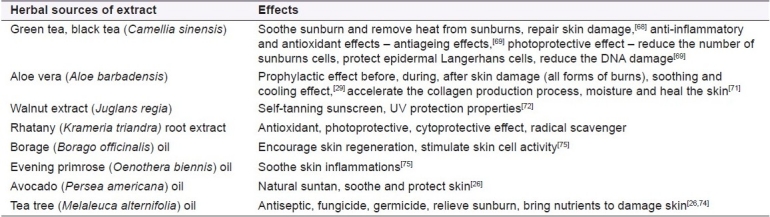

The complex polyphenolic compounds in tea provide the same protective effect for the skin as for internal organs. They have been shown to modulate biochemical pathways that are important in cell proliferation, inflammatory responses, and responses of tumor promoters. Green tea has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in both human and animal skin.[78] Animal studies provide evidence that tea polyphenols, when applied orally or topically, ameliorate adverse skin reactions following UV exposure, including skin damage, erythema, and lipid peroxidation.[79] Since inflammation and oxidative stress appear to play a significant role in the aging process, green tea may also have antiaging effects by decreasing inflammation and scavenging free radicals. Researchers have found that the main active ingredient in green tea, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), works well as an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and sunscreen. Topical green tea applied to human skin provide a photoprotective effect, reduced the number of sunburns cells, protecting epidermal Langerhans cells from UV damage, and reduced the DNA damage that formed after UV radiation. Green tea was also found to decrease melanoma cell formation with topical and oral administration in mice. Most cosmeceuticals products containing tea extracts or phenols have not been tested in controlled clinical trials, but these substances have shown compelling evidence for antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic activities[78] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Whole herbal extract in use

Aloe vera

The reputable Aloe vera or Aloe barbadensis has been scientifically proven for all forms of burn, be it radiation, thermal, or solar. It has also been demonstrated that it has a prophylactic effect if used before, during, and after these skin damaging events. Clearly, the plant is mainly used for its soothing and cooling effect; however, the plant is useless if used at less than 50% and it is recommended that it is used at 100% to be sure of any beneficial effect. The polysaccharides, mannose-6-phosphate, and complex anthraquinones all contribute synergistically to the benefits of this material.[30] The natural chemical constituents of Aloe vera can be categorized in the following main areas: Amino acids, anthraquinones, enzymes, lignin, minerals, mono- and polysaccharides, salicylic acid, saponins, sterols, and vitamins. Aloe vera not only improved fibroblast cell structure, but also accelerated the collagen production process. Aloe vera is a uniquely effective moisturizer and healing agent for the skin (both human and animal!!!)[80] [Table 2].

Walnut

Walnut extract is made from the fresh green shells of English walnut, Juglans regia. The aqueous extract has been shown to be particularly effective as a self-tanning sunscreen agent. Its most important component is juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4- naphthoquinone), a naphthol closely related to lawsone (2-hydroxy-1,4- naphthoquinone). Juglone is known to react with the keratin proteins present in the skin to form sclerojuglonic compounds. These are colored and have UV protection properties[81] [Table 2].

Krameria triandra

The antioxidant/photoprotective potential of a standardized Krameria triandra root extract (15% neolignans) has been evaluated in different cell models, rat erythrocytes, and human keratinocytes cell lines, exposed to chemical and physical (UVB radiation) free radical inducers. In cultured human keratinocytes exposed to UVB radiation, Krameria triandra root extract significantly and dose-dependently restrained the loss in cell viability and the intracellular oxidative damage. The cytoprotective effect of the extract was confirmed in a more severe model of cell damage: Exposure of keratinocytes to higher UVB doses, which induce a 50% cell death. In keratinocyte cultures supplemented with 10 μg/ml, cell viability was almost completely preserved and more efficiently than with (-)-EGCG and green tea. The results of this study indicate the potential use of Rhatany extracts, standardized in neolignans, as topical antioxidants/radical scavengers against skin photodamage[82] [Table 2].

Plant oils as sunscreens

Researchers have found that some plant oils contain natural sunscreens. For example, sesame oil resists 30% of UV rays, whereas coconut, peanut, olive, and cottonseed oils block out about 20%. Although mineral oil does not resist any UV rays, it helps to protect skin by dissolving the sebum secreted from oil glands, thus assisting evaporation from the skin.[27,83]

Borage oil

Borage (Borago officinalis) oil stimulates skin cell activity and encourages skin regeneration. It contains high levels of gamma-linoleic acid (GLA), making it useful in treating all skin disorders, particularly allergies, dermatitis, inflammation, and irritation. Borage penetrates the skin easily and benefits all types of skin, particularly dry, dehydrated, mature, or prematurely aging skin[84] [Table 2].

Evening primrose oil

Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) oil has a high GLA content that promotes healthy skin and skin repair. It is usually yellow in color. It soothes skin problems and inflammation, making it a good choice for people with eczema, psoriasis, or any type of dermatitis. Evening primrose skin oil discourages dry skin and premature aging of the skin[84] [Table 2].

Avocado oil

High-quality, natural suntan and after-sun products are found in abundance at natural food stores. Avocado (Persea americana) oil is rich in vitamin E, β–carotene,[27] vitamin D, protein, lecithin, and fatty acids[85] and offers considerable benefits when added to preparations. From avocado oil to botanicals such as rosemary and comfrey, these ingredients soothe and protect the skin[27] [Table 2].

Tea tree oil

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil is an ancient aboriginal remedy. It is an effective antiseptic, fungicide, and germicide. It is a popular component of many sunscreen formulations that relieve sunburn by increasing blood flow in capillaries, bringing nutrients to damaging skin[27,83] [Table 2].

Porphyra

Porphyra (Bangiales, Rhodophyta), delicious red algae widely consumed in eastern Asia, contains high levels of free amino acids; when exposed to intense radiations, it synthesizes UV-absorbing secondary metabolites such as mycosporine-like amino acids. There are almost seven species of Porphyra identified in India. Among all of these, nowadays Porphyra vietnamensis are gaining more attention. Marketed Aloe vera gel had low absorption power over broad UV wavelength (250-400 nm) as compared with isolated compound gel, suggesting that Porphyra-334 is more potent.[2]

FUTURE TRENDS FOR SUNSCREENS

The growing consumer awareness of the dangers of the sun has influenced the cosmetics industry and the sun care segment in particular. Human skin is constantly exposed to the UV irradiation present in sunlight.[59] The consumer wants products that enable them to stay in the sun for a longer period of time. Most products are targeted at a specific market and nearly every manufacturer has a complete range of products—sunless tanners, high SPF sunblocks, tanning lotions. The most recent introductions have focused on products for children, athletes, or for those who want UVA protection. These niche markets have enhanced sales for several years. In the past two years, most cosmetic companies have launched products containing sunscreens, moisturizers, antioxidants, or a combination of all three.[27] The development of novel preventive and therapeutic strategies depends on our understanding of the molecular mechanism of UV-damage.

The newest trend will be to stay continuously cool, while remaining in the sun. Cooling is achieved through evaporating water, alcohol, or any other low-density vapor-producing solvents or materials that leave a cooling effect on the skin. Thanks to the encapsulating technology that can deliver water or other cooling agents with intermittent release through a rub mechanism. This will provide some relief to the body from very high temperature in the sun without compromising SPF numbers. Other forms are an intermittent spray/water-based thin emulsion, containing sunscreens, menthol, and cooling esters with continuous intact SPF number and hydro-alcohol-based systems, with silicone and cooling esters in a thin light gel vehicle and a fresh fragrance note.[27] Also, it is necessary to improve the effectiveness of sunscreens by increasing skin accumulation of UV absorbers with minimal permeation to the systemic circulation. An ideal product with cosmetic appeal can be constructed in the form of a thin sprayable gel with a film-forming polymer combined with emollients and cooling ingredients.[77]

Numbers of conventional and novel herbal cosmetics are useful to treat damaged skin.[86–89] Herbal sunscreens are rapidly replacing the modern sunscreen containing UV-filters due to associated side effects with UV filters. Many herbal sunscreens are available in market in the form of creams, lotion, and gel having labeled SPF.[89] Also, there are plants available that have given indications of protecting themselves from intense heat and UV radiation from the sun and they are interesting for researchers. The identification of naturally derived sunscreens from the herbs is not impossible, and it requires more concerted efforts.[27]

CONCLUSION

UV radiation cause skin damages. Everybody needs protection from harmful UV lights. There are many different ways to protect our skin. The best way is avoiding direct sun exposure. But sometimes, it can be impossible, especially during summer. Because of that, sunscreen products should be used.

Consumers request high-quality products with accessible prizes. It means that they want to get everything when they apply these products. All in one: Protection skin from UV radiation, antiaging and wrinkles reduction, moisturizing and cooling effects on the skin without allergic reaction, and coloring effects on the skin. This request is the main guide for scientists and researchers. Also, they know that chemical components sometimes have harmful effects on the skin. Because of that, they more and more choose products with natural components.

Using natural ingredients in different skin care products is very popular today. Plants’ ability to protect themselves from UV radiation from the sun is the main reason for that. Plants have a good potential to help us. Plant phenolics are one candidate for prevention of harmful effects of UV radiation on the skin. Additionally, plants contain a lot of other substances which can be useful for skin care. Their potential is still undefined. Nevertheless, more research trials and clinical evidences are needed.

It was shown that using only one natural component is not enough for skin protection. Maybe, combination of several different natural substances is a right solution. It will be ideal to make the product with natural components only, without any harmful effects. Also, it is necessary to find out in which form this combination is stable and has the best effects. There are many products with natural ingredients that are available in the world's market. But, there is no product which can accomplish all requests of consumers. This is the main direction for new product development.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Tuchinda C, Srivannaboon S, Lim WH. Photoprotection by window glass, automobile glass and sunglasses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia S, Sharma K, Namdeo AG, Chaugule BB, Kavale M, Nanda S. Broad-spectrum sun-protective action of Porphyra-334 derived from Porphyra vietnamensis. Phcog Res. 2010;2:45–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.60578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kullavanijaya P, Henry W, Lim HW. Photoprotection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:959–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer H, Moyal D, Fourtanier A. Recent advances in sun protection. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:266–75. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almahroos M, Kurban AK. Ultraviolet carcinogenesis in nonmelanoma skin cancer. Part I: incidence rates in relation to geographic locations and in migrant populations. Skinmed. 2004;3:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2004.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings SR, Tripp MK, Herrmann NB. Approaches to the prevention and control of skin cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1997;16:309–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1005804328268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sliney DH. Photoprotection of the eye - UV radiation and sunglasses. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;64:166–75. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young RW. Sunlight and age-related eye disease. J Nat Med Assoc. 1992;84:353–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young AR. Are broad-spectrum sunscreens necessary for immunoprotection? J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:9–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azevedo JS, Viana NS, Jr, Vianna Soares CD. UVA/UVB sunscreen determination by second-order derivative ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Farmaco. 1999;54:573–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(99)00063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gil EM, Kim TH. UV-induced immune suppression and sunscreen. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2000;16:101–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2000.d01-14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarrera M. Age and skin response to ultraviolet radiation. J Cutan Ageing Cosmetic Dermatol. 1988/89;1:135–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF, Anderson RR. Erythema and melanogenesis action spectrum of normal human skin. Photochem Photobiol. 1982;36:187–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1982.tb04362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH Consensus statement: Sunlight, ultraviolet radiation and the skin excerpts. NIH Consensus Statement. Md Med J. 1990;39:851–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaidbey KH, Kligman AM. The acute effects of longwave ultraviolet light upon human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;72:253–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibbotson SH, Farr PM. The time-course of psoralen ultraviolet A (PUVA) erythema. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:346–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parrish JA, Anderson RR, Ying CY, Pathak MA. Cutaneous effects of pulsed nitrogen gas laser irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1976;67:603–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawk JL, Black AK, Jaenicke KF, Barr RM, Soter NA, Mallett AI, et al. Increased concentrations of arachidonic acid, prostaglandin E2, D2, and 6-oxo-F1 alpha, and histamine in human skin following UVA irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;80:496–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12535038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyal D, Fourtanier A. Acute and chronic effects of UV on skin: What are they and how to study them? In: Rigel DS, Weiss RA, Lim HW, Dover JS, editors. Photoaging. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 2004. pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mithal BM, Saha RN. A Handbook of Cosmetics. New Delhi: Vallabh Prakashan; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vimaladevi M. Textbook of Cosmetics. 1st ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasiljević D, Savić S, Ðorđević Lj, Krajišnik D. Priručnik iz kozmetologije. Beograd: Nauka; 2007. pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlossman D. Sunscreen Technologies for Foundations and Lipsticks. Nice (France): Kobo Products, Inc; 2001. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freund RM, editor. A more beautiful you: Reverse Aging Through Skin Care, Plastic Surgery, and Lifestyle Solutions. New York: Sterling Publishing Co. Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao Y, Schlossman D. Effect of Particle Size on Performance of Physical Sunscreen Formulas, Presentation at PCIA Conference. Shanghai, China R.P: 1999. Kobo Products, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen U, Schlossman D. Stability Study of Avobenzone with Inorganic Sunscreens, Kobo Products Poster Presentation, SSC New York Conference. 2001 Dec [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mufti J. UV Protection. Household and Personal Products Industry. 2003. Jun, [Last accessed on 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.happi.com/articles/2003/06/uv-protection .

- 28.Skin Biology Aging Reversal, At Home Use of SRCPs for Different Skin Types and Skin Problems. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.skinbiology.com/skinrenewalmethods.html .

- 29.Bensouilah J, Buck P, Tisserand R, Avis A. Aromadermatology: Aromatherapy in the Treatment and Care of Common Skin Conditions. Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dweck AC. Herbal medicine for the skin – their chemistry and effects on skin and mucous membranes. Pers Care Mag. 2002;3:19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allantoin. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.balmtech.com/db/upload/webdata12/13Allantoin.pdf .

- 32.Majo DD, Guardia ML, Giammanco S, Neve LL, Giammanco M. The antioxidant capacity of red wine in relationship with its polyphenolic constituents. Food Chem. 2008;111:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browden J. Unleash the Amazingly Potent Anti-Aging, Antioxidant Pro-Immune System Health Benefits of the Olive Leaf. Topanga: Freedom Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuda T. The role of anthocyanins as an antioxidant under oxidative stress in rats. Biofactors. 2000;13:133–9. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520130122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuda T. Dietary cyanidin 3-0-beta-D-glucoside increases ex vivo oxidative resistance of serum in rats. Lipids. 1998;33:583–8. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice-Evans CA. The relative antioxidant activities of plant-derived polyphenolic flavonoids. Free Radical Res. 1995;22:3785–93. doi: 10.3109/10715769509145649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuda T. Mechanism for the peroxynitrite scavenging activity by anthocyanins. FEBS Lett. 2000;484:207–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noda Y. Antioxidant activity of nasunin, an anthocyanin in eggplant peels. Toxicology. 2000;148:119–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertuglia S, Malandrino S, Colantuoni A. Effect of Vaccinium myrtillus anthocyanosides on ischemia reperfusion injury in hamster cheek pouch microcirculation. Pharmacol Res. 1995;31:183–7. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(95)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Netherlands: i.BioCeuticals,™llc; 2008. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar]. Masquelier's® OPCs and French Maritime Pine Bark Extract. Available from: http://ibioceuticals.com/docs/Masquelier.IBC_Brochure.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wellness Advocate OPC-Proanthocyanidin. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar];A Total Wellness Newsletter. 1994 4:1–4. Available from: http://www.personalhealthfacts.com/antioxidants9.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murdock KA, Schauss AG. Jucara and acai fruit-based dietary supplements, Patent 7563465. 2009. Jul, [Last accessed on 2011 Mar]. Available from: http://www.freepatentsonline.com/7563465.html .

- 43.Baliga MS, Katiyar SK. Chemoprevention of photocarcinogenesis by selected dietary botanicals. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5:243–53. doi: 10.1039/b505311k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saraf S, Kaur CD. Phytoconstituents as photoprotective novel cosmetic formulations. Phcog Rev. 2010;4:1–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.65319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goyal A, Singh J, Jain S, Pathak DP. Phytochemicals as potential antimutagens. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar];Int J Pharm Res Dev. 2009 7:1–13. Available from: http://ijprd.com/PHYTOCHEMICALS%20AS%20POTENTIAL%20ANTIMUTAGENS.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumann L. Chap. 34. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill Professional Inc; 2009. Antioxidants. Cosmetic dermatology: Principle and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Counet C, Callemien D, Collin S. Chocolate and cocoa: New sources of trans-resveratrol and trans-piceid. Food Chem. 2006;98:649–57. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Catana F, Yang Y, Roderick R, van Breemen RB. An LC-MS method for analysing total resveratrol in grape juice, cranberry juice, and in wine. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:431–5. doi: 10.1021/jf010812u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanders TH, McMichael RW, Hendrix KW. Occurrence of resveratrol in edible peanuts. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:1243–6. doi: 10.1021/jf990737b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vastano BC, Chen Y, Zhu N, Ho C-T, Zhou Z, Rosen RT. Isolation and identification of stilbenes in two varieties of Polygonum cuspidatum. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:253–6. doi: 10.1021/jf9909196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soleas GJ, Diamandis EP, Golberg DM. Resveratrol: A molecule whose time has come? And gone? Clin Biochem. 1997;30:91–113. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(96)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erlund I. Chemical analysis and pharmacokinetics of the flavonoids quercetin, hesperetin and naringenin in humans, Academic dissertation. Helsinki: University of Helsinki; 2002. National Public Health Institute, University of Helsinki, Department of Health and Functional Capacity. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green RJ. Natural Therapies for Emphysema and COPD: Relief and Healing for Chronic Pulmonary Disorders. Vermont: Inner Traditions / Bear and Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verma AK, Johnson JA, Gould MN, Tanner MA. Inhibition of 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene- and N-nitrosomethylurea-induced rat mammary cancer by dietary flavonol quercetin. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5754–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deschner EE, Ruperto J, Wong G, Newmark HL. Quercetin and rutin as inhibitors of azoxymethanol - induced colonic neoplasia. Carcinogenesis. 1991;12:1193–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/12.7.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makita H, Tanaka T, Fujitsuka H, Tatematsu N, Sato H, Hara A, et al. Chemoprevention of 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide-induced rat oral carcinogenesis by the dietary flavonoids chalcone, 2-hydroxychalchone, and quercetin. Cancer Res. 1996;59:4904–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishino H, Iwashima A, Fujiki H, Sugimura T. Inhibition by quercetin of the promoting effect of teleocidin on skin papilloma formation in mice initiated with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. Gann. 1984;75:113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Błasiak J. DNA-Damaging Effect of Cadmium and Protective Action of Quercetin, Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Łódź. Pol J Environ Stud. 2001;10:437–42. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svobodová A, Psotová J, Walterová D. Natural phenolics in the prevention of UV- induced skin damage. Biomed Papers. 2003;147:137–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choquenet B, Couteau C, Paparis E, Coiffard IJ. Quercetin and rutin as potential sunscreen agents: Determination of efficacy by an in vitro method. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1117–8. doi: 10.1021/np7007297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kris-Etherton PM, Lefevre M, Beecher GR, Gross MD, Keen CL, Etherton TD. Bioactive compounds in nutrition and health-researchmethodologies for establishing biological function: The Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Flavonoids on Atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004;24:511–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Natural Ingredients for colouring the hair. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2002;24:287–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2002.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katiyar SK, Korman NJ, Mukhtar H, Agarwal R. Protective effects of silymarin against photocarcinogenesis in a mouse skin model. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:556–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.8.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katiyar SK. Treatment of silymarin, a plant flavonoid, prevents ultraviolet light-induced immune suppression and oxidative stress in mouse skin. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1213–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.García-Bores AM, Avila JG. Natural products: Molecular mechanisms in the photochemoprevention of skin cancer. Rev Latinoamer Quím. 2008;36:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bechtold T, Mussak R. Handbook of natural colorants. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Motohashi N, editor. Bioactive heterocycles VI: Flavonoids and anthocyanins in plants and lates bioactive heterocycles I. Vol. 6. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Higdon J. An evidence-based approach to dietary phytochemicals. New York: Thieme Medical; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hoffmann D. Medical herbalism: The science and practice of herbal medicine. Rochester: Inner Traditions/Bear and Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hupli H. Best Life and Health. Parker: Outskirts Press, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barceloux DG. Medical toxicology of natural substances: Foods, fungi, medicinal herbs, plants, and venomous animals. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fryer MJ. Evidence for the photoprotective effects of vitamin E. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;58:304–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb09566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayer P, Pittermann W, Wallat S. The effects of vitamin E on the skin. Cosmet Toiletries. 1993;108:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Your Prescription for Ageless skin. Vienna: You look so young LLC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dayan N. Skin aging handbook: An Integrated Approach to Biochemistry and Product Development. New York: William Andrew Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kapoor S, Saraf S. Assessment of viscoelasticity and hydration effect of herbal moisturizers using bioengineering techniques. Phcog Mag. 2010;6:298–304. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.71797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duke JA. The green pharmacy: New discoveries in herbal remedies for common diseases and conditions from the world's foremost authority on healing herbs. New York: St. Martin Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hirsch RJ, Sadick N, Cohen JL, editors. Aesthetic Rejuvenation: A Regional Approach. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008. Chapter 3: New generation cosmeceutical agents. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou J, Jang YP, Kim SR, Sparrow JR. Complement activation by photooxidation products of A2E, a lipofuscin constituent of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:16182–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604255103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barcroft A, Myskja A. Aloe Vera: Nature's Silent Healer. London: BAAM Publishing Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dweck AC. FLS FRSC FRSPH – Technical Editor. Colour cosmetics: Comprehensive focus on natural dyes. Pers Care. 2009;2,3:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carini M, Aldini G, Orioli M, Facino RM. Antioxidant and photoprotective activity of a lipophilic extract containing neolignans from Krameria triandra roots. Planta Med. 2002;68:193–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burgess CM. Chapter 70: Cosmetic products. In: Kelly AP, Taylor SC, editors. Dermatology for Skin of Color. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wilson R. Aromatherapy: Essential Oils for Vibrant Health and Beauty, Part one: The basic principle of aromatherapy. New York: Penguin Putman Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loughran J. Natural Skin Care: Alternative and traditional techniques. New Delhi: B. Jain Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ashawat MS, Saraf S, Saraf S. Phytosomes: A novel approach towards functional cosmetics. J Plant Sci. 2007;2:644–9. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kaur CD, Saraf S. Novel approaches in herbal cosmetics. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:89–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2008.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ashawat MS, Gupta A, Saraf S, Swarnlata S. Role of highly specific and complex molecule in skin care. Int J Can Res. 2007;3:191–5. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kapoor S, Saraf S. Efficacy Study of Sunscreens Containing Various Herbs for Protecting Skin from UVA and UVB Sunrays. Phcog Mag. 2009;5:238–48. [Google Scholar]