Abstract

Background:

In women, cancer of the breast is one of the most common incident cancer and cause of death from cancer. Anthropometric factors of weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) have been associated with breast cancer risk.

Objectives:

To study the association of overweight and obesity with breast cancer in India.

Materials and Methods:

A hospital-based matched case-control study was conducted. Three hundred and twenty newly diagnosed breast cancer patients and three hundred and twenty normal healthy individuals constituted the study population. The subjects in the control group were matched individually with the patients for their age ±2 years and socioeconomic status. Anthropometric measurements of weight and height were recorded utilizing the standard equipments and methodology. The paired ‘t’ test and univariate logistic regression analysis were carried out.

Results:

It was observed that the patients had a statistically higher mean weight, body mass index, and mid upper arm circumference as compared to the controls. It was observed that the risk of breast cancer increased with increasing levels of BMI. Overweight and obese women had Odd's redio of 1.06 and 2.27, respectively, as compared to women with normal weight.

Conclusions:

The results of the present study revealed a strong association of overweight and obesity with breast cancer in the Indian population.

Keywords: Breast cancer, case-control study, India, obesity, overweight

Introduction

In women, cancer of the breast is one of the most common incident cancer and cause of death from cancer.(1) Anthropometric factors of weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) have been associated with breast cancer risk.(2,3) Obesity leads to increased levels of fat tissue in the body that can store toxins and can serve as a continuous source of carcinogens.(4) Body fat is an important locus of endogenous estrogen production and storage, and hence, could increase the risk of breast cancer.(5) There is considerable evidence that free estrogen levels are raised in obese women, especially in those with abdominal (visceral) obesity.(6) Also, there is an increase in the bioavailable estrogen fraction which may promote tumor growth, either directly or by modulating steroid activity and has been implicated as a risk factor for breast cancer.(7–13) Though a large number of women are affected with breast cancer, there is paucity of data on the association of anthropometry with breast cancer in the Indian population. Hence, we conducted a hospital-based case-control study to identify the association of overweight and obesity with breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a hospital-based matched case-control study conducted in the year 2001–2003. Three hundred and twenty newly diagnosed breast cancer patients (all consecutive cases) from the out-patient and hospital admissions of the Departments of Surgery/Surgical Oncology at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, constituted the study population. The criteria for selection of the patients was i) they should be proven cases of breast cancer by histopathology/cytopathology; ii) they should have not undergone any treatment specific for breast cancer; iii) they should not have suffered from any major chronic illness in the past, before the diagnosis of breast cancer so as to change their dietary pattern; iv) they should not have taken long course of any vitamin or mineral supplements during the last one year; and v) they should not be on corticosteroid therapy or suffering from hepatic disorders/severe malnutrition.

Three hundred and twenty normal healthy individuals accompanying the patients in the Department of Gastroenterology, Medicine and Surgery at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, and at Comprehensive Rural Health Services Project at Ballabgarh Hospital, Faridabad, Haryana, constituted the control group. The subjects in the control group were matched individually with the patients for their age ±2 years and socioeconomic status. The criteria for selection of the controls was i) the attendants of patients who did not suffer from any major illness in the past; ii) they should not have taken long course of any vitamin or mineral supplements during the last one year; and iii) they should not be on corticosteroid therapy or suffering from hepatic disorders or severe malnutrition. The study was ethically approved by the Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. All the investigations to be performed were explained to the subjects and those who consented for participation were included in the study.

The patient and control groups were subjected to similar investigations. A pretested, semistructured questionnaire was administered to each individual to collect information on identification data and sociodemographic profile. Anthropometric measurements of weight and height were recorded utilizing the standard equipments and methodology.(14)

Weight was recorded using SECA electronic weighing scale, to the nearest 100 g. The subjects were asked to be barefoot and with light clothing. She was asked to stand straight on the electronic weighing scale and the weight displayed on the screen was recorded. Height was recorded using the anthropometric height rod to the nearest 0.1 cm. The subject was asked to stand straight with head position such that Frankfurt plane is horizontal, feet together, knees, heels and shoulder blades straight, arms hanging loosely on either side with palms facing the thighs. The anthropometric rod was placed between the shoulder blades and the height measured. Body mass index was calculated using the standard formula. Accordingly, the nutritional status was defined as follows: i) BMI 20–24.9 (normal); ii) BMI 25–29.9 (overweight); and iii) BMI ≥ 30 (obesity). The mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a fiber glass tape. The left mid upper arm circumference was measured, while hanging the arm freely and gently placing the tape round the limb at its midpoint.(14)

The paired ‘t’ test was utilized to compare the mean anthropometric values between breast cancer patients and controls. The result was considered significant at 5% level of significance. The univariate logistic regression analysis was also carried out to calculate the odds ratios and the confidence intervals.

Results

A total of 320 breast cancer patients and 320 matched controls were enrolled for the present study. The mean age of the patients and controls was 45.5 and 40.98 years, respectively. Majority of the patients (61.9%) belonged to urban area of residence. All the patients were married and about 95.9% of the patients and 95.6% of the controls were housewives. Nearly 37.2 and 35.9% of the patients and controls were illiterate, respectively. The socioeconomic status of the patients was significantly higher as compared to the controls. Forty six percent of the patients and 36.3% of the controls belonged to lower middle socioeconomic status.

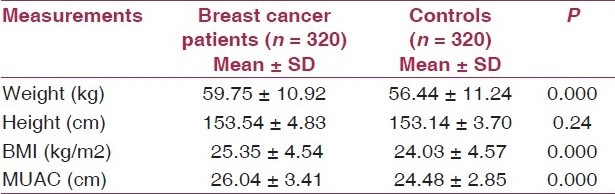

The distribution of breast cancer patients and controls according to their mean anthropometric measurements is depicted in Table 1. It was observed that the patients had a statistically higher mean weight (59.75 ± 10.92 kg) as compared to the controls (56.44 ± 11.24 kg). The patients and controls had no significant difference with respect to their mean height. The mean BMI and MUAC were also found to be significantly higher in patients as compared to the controls.

Table 1.

Mean anthropometric measurements of breast cancer patients and controls

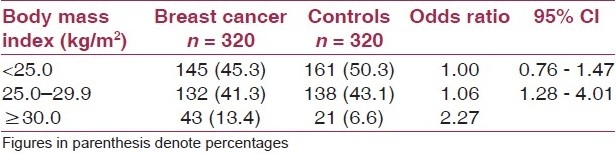

It was observed that 13.4% of the patients and 6.6% of the controls were obese according to their BMI. It was observed that the risk of breast cancer increased with increasing levels of BMI. Overweight and obese women had OR of 1.06 (95% CI: 0.76–1.47) and 2.27 (95% CI: 1.28–4.01) as compared to women with normal weight [Table 2].

Table 2.

Unadjusted relative risk for breast cancer according to body mass index

Discussion

The breast cancer patients had a statistically higher mean weight, BMI, and MUAC as compared to the controls. Obesity and weight gain are positively associated with serum concentrations of endogenous estrogens leading to moderate elevations in both the incidence and mortality from the disease, thus affecting breast cancer growth and metastasis.(15,16) A study conducted in USA revealed that the adjusted OR for women weighing over 81 kg relative to women weighing under 63 kg was 2.1; 95% CI: 1.3–3.2.(17) An earlier case–control study conducted in Ireland revealed that BMI was significantly higher in cases (26.2 kg/m2) as compared to controls (24.5 kg/m2) (P < 0.05).(18)

It was observed that the risk of breast cancer increased with increasing levels of BMI. Overweight and obese women had OR of 1.06 (95% CI: 0.76–1.47) and 2.27 (95% CI: 1.28–4.01) as compared to women with normal weight. An earlier case-control study conducted in USA revealed that the risk of breast cancer increased with increasing levels of BMI. Overweight and obese women had OR of 1.14 (95% CI: 0.96–1.36) and 1.22 (95% CI: 0.99–1.50) as compared to women at normal weight.(19) Meta analysis of case control data from countries at high, moderate, and low risk for breast cancer demonstrated that breast cancer incidence rates consistently increased with adiposity among both premenopausal and post menopausal women.(20) Similar results have been shown by other studies.(21–27) The results of the present study revealed a strong association of overweight and obesity with breast cancer in the Indian population. Hence, weight control may be a modifiable risk factor for breast cancer prevention and thus may have significant public health impact in women.

Acknowledgment

We are extremely grateful to the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, for providing us the financial assistance for conducting the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Parkin DM. Cancers of the breast, endometrium and ovary: geographic correlations. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1989;25:1917–25. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(89)90373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin TM, Chen KP, MacMohan B. Epidemiological characteristics of cancer of the breast in Taiwan. Cancer. 1971;27:1497–504. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197106)27:6<1497::aid-cncr2820270634>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li CI, Malone KE, White E, Daling JR. Age when maximum height is reached as a risk factor for breast cancer among young U.S. Epidemiology. 1997;8:559–65. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199709000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and cancer: lessons learned from nutritional epidemiology. Nutr Rev. 2001;59:349–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb06962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham S, Hellmann R, Marshall J, Freudenheim J, Vena J, Swanson M, et al. Nutritional epidemiology of postmenopausal breast cancer in western New York. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:552–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoll BA. Diet and exercise regimens to improve breast carcinoma prognosis. Cancer. 1996;78:2465–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Key TJ, Pike MC. The role of estrogens and progestragens in the epidemiology and prevention of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schapira DV, Kumar NB, Lyman GH, Cox CE. Abdominal obesity and breast cancer risk. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:182–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-3-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein L, Ross RK. Endogenous hormones and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:48–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard-Barbash R. Anthropometry and breast cancer: body size- a moving target. Cancer. 1994;74(3 Suppl):1090–100. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940801)74:3+<1090::aid-cncr2820741518>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Giudice ME, Fantus IG, Ezzat S, McKeown-Eyssen G, Page D, Goodwin PJ. Insulin and related factors in premenopausal breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;47:111–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1005831013718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persson I. Estrogens in the causation of breast, endometrial and ovarian cancers- evidence and hypothesis from epidemiological findings. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74:357–64. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verkasalo PK, Thomas HV, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Circulating levels of sex hormones and their relation to risk factors for breast cancer: a cross-sectional study in 1092 pre- and postmenopausal women (United Kingdom) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:47–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1008929714862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organisation Technical Report Series 854. Geneva: WHO; 1995. Physical status: The use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee; pp. 427–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byers T. Nutritional risk factors for breast cancer. Cancer. 1994;74(1 Suppl):288–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820741313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michels KB. The contribution of the environment (especially diet) to breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:58–61. doi: 10.1186/bcr423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam PB, Vacek PM, Geller BM, Muss HB. The association of increased weight, Body mass index and tissue density with the risk of breast carcinoma in Vermont. Cancer. 2000;89:369–75. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<369::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strain JJ, Bokje E, van’t Veer P, Coulter J, Stewart C, Logan H, et al. Thyroid hormones and selenium status in breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 1997;27:48–52. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carpenter CL, Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Bernntein L. Effect of family history, obesity and exercise on breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:96–102. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pathak DR, Whittemore AS. Combined effects of body size, parity, and menstrual events on breast cancer incidence in seven countries. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:153–68. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tornberg SA, Carstensen JM. Relationship between Quetelet's index and cancer of breast and female genital tract in 47,000 women followed for 25 years. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:358–61. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Z, Parviainen M, Männistö S, Pietinen P, Eskelinen M, Syrjänen K, et al. Vitamin E concentration in breast adipose tissue of breast cancer patients (Kuopio, Finland) Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:591–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00051701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galanis DJ, Kolonel LN, Lee J, Le Marchand L. Anthropometric predictors of breast cancer incidence and survival in a multi-ethnic cohort of female residents of Hawaii, United states. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:217–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1008842613331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirose K, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Inoue M, Kuroishi T, et al. Effect of body size on breast-cancer risk among Japanese women. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:349–55. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990129)80:3<349::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirose K, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Inoue M, Kuroishi T, et al. Association of family history and other risk factors with breast cancer risk among Japanese premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:349–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1011232602348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michels KB, Holmberg L, Bergkvist L, Ljung H, Bruce A, Wolk A. Dietary antioxidant vitamins, retinol, and breast cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish women. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:563–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1079>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanderson M, Shu XO, Jin F, Dai Q, Wen W, Hua Y, et al. Abortion history and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:899–905. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]