Abstract

A 46-year-old diabetic male presented with acute painless visual loss in his left eye (OS). Visual acuity was 6/36 OS with an unremarkable anterior segment examination (OU). Posterior segment showed a swollen left optic disc with large diffuse macular edema and moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). The right eye fundus showed only mild NPDR. Optical coherence tomography and fundus fluorescein angiography were performed which revealed left macular edema and a hyperfluorescent left optic disc. Computerized tomography scan orbit and brain was normal. The patient received an intravitreal bevacizumab injection OS followed by focal laser photocoagulation 1 month later. His optic disc swelling and the macular edema subsided rapidly after the injection and his visual acuity improved to 6/6 with disc pallor.

Keywords: Bevacizumab, diabetic papillopathy, macular edema

Introduction

Diabetic papillopathy (DP) is a rare condition that occurs in diabetic patients (types 1 and 2). Its prevalence is 1.4% in diabetic patients,[1] and the exact pathogenesis is uncertain. Some risk factors include rapid improvement of the metabolic control and a small cup-to-disc ratio.[2] One study suggested that DP could be a mild form of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.[3] DP is unilateral in 50% of the cases.[1] Diabetic retinopathy in eyes with DP tends to progress with time.[1]

Visual prognosis is usually good in cases of DP.[1] The disc swelling tends to resolve spontaneously within 3–4 months.[4] However, in very few case reports treatment with intravitreal corticosteroids or antivascular endothelial growth factors was suggested. Literature search was performed, and three reports of treatment with intravitreal injections were found: one with an intravitreal triamcinolone acetate injection and the other two with an intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection.[5–7] In all three cases, visual acuity and disc swelling improved rapidly after the treatment. Periocular corticosteroid injection had been described, too.[8]

Case Report

Our case was a 46-year-old man, known to have type 2 diabetes mellitus for 10 years and hypertensive for 2 years, on oral hypoglycemic and hypotensive agents, presented to the eye clinic with painless blur of vision in his left eye (OS) of 4 days duration. His best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6/6 in the right eye (OD) and 6/36 OS with a correction of -0.75 -0.62 ×180 and +0.75 -3.25 ×70, respectively. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 14 mm Hg in each eye (OU). The anterior segment examination was unremarkable (OU). There was mild relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) OS. Posterior segment examination [Figures 1 and 2] showed mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy without diabetic macular edema and a normal looking optic disc OD with a small cup-to-disc (CD) ratio (0.1). The OS posterior segment showed a swollen optic disc with telangiectasic vessels and a small CD ratio. There was also diffuse but not cystic, macular edema involving the papillomacular bundle with moderate NPDR. Subfoveal fluid was absent. There were no signs of proliferative disease OU. A CT scan of the brain and orbit was done and did not show any abnormalities. Optical coherent tomography (OCT) was normal OD. However, it revealed significant macular edema with a central macular thickness of 582 μm [Figures 3 and 4] OS. Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) OD revealed few microaneurysms, otherwise no evidence of macular or disc leakage. However, FFA OS demonstrated tremendous amount of early optic disc and macular leakage with the presence of microaneurysms, [Figures 5 and 6]. Glycosylated hemoglobin was 12.2%. A formal visual field test was not performed because of a technical reason.

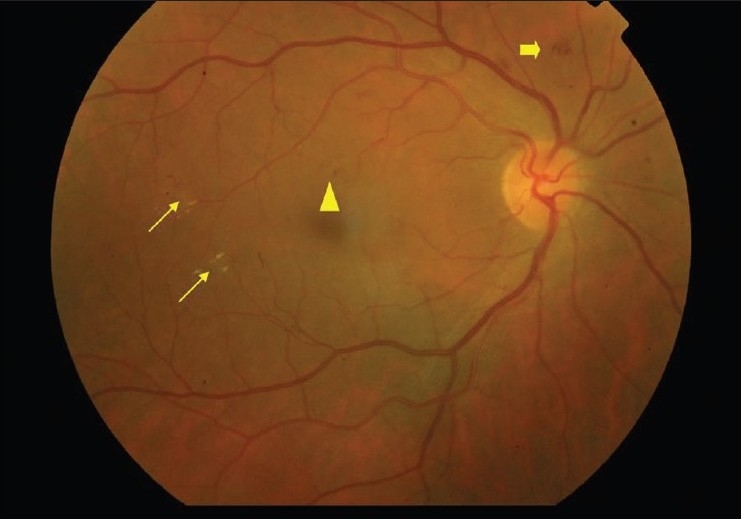

Figure 1.

OD at presentation with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Thin arrows: hard exudates; Thick arrow: blot intra-retinal hemorrhage; triangle: microaneurysm

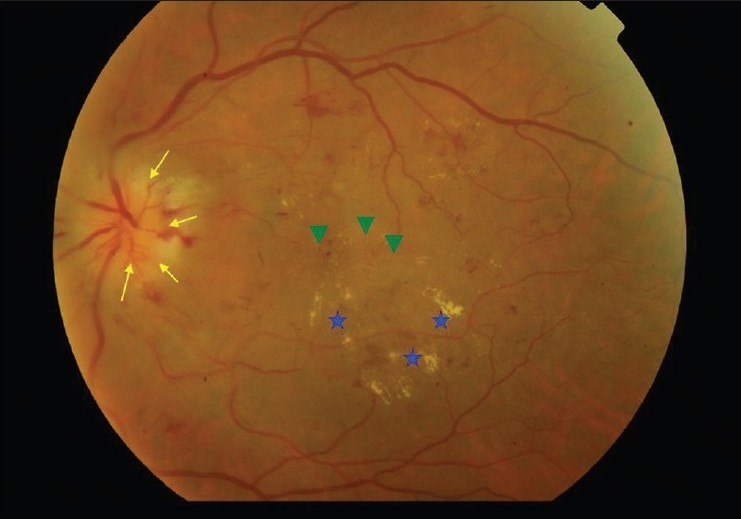

Figure 2.

OS at presentation, Thin arrows: swollen optic disc; stars: hard exudates; arrow heads: area of macular edema

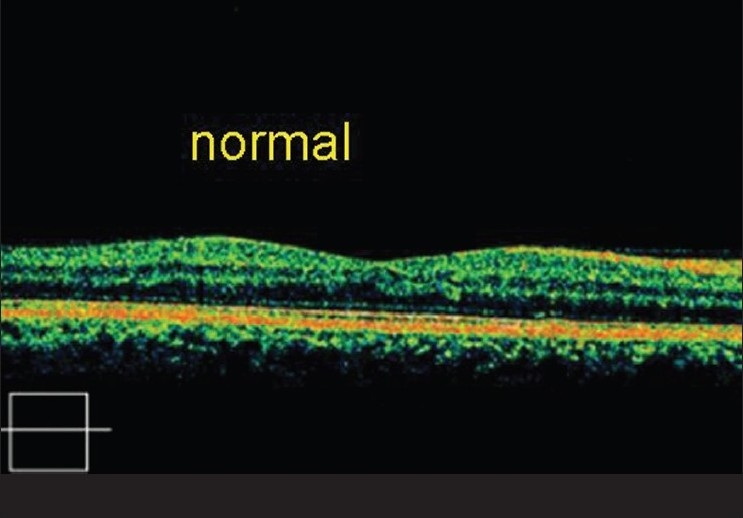

Figure 3.

Optical coherent tomography of OD at presentation

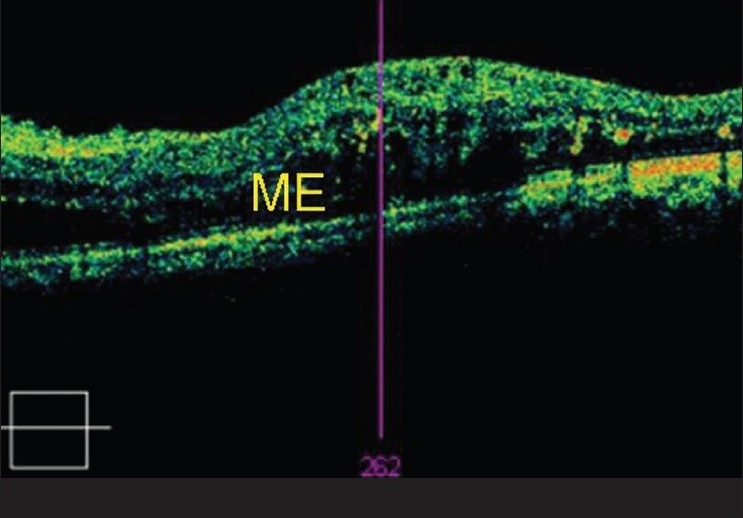

Figure 4.

Optical coherent tomography of OS at presentation. ME= macular edema

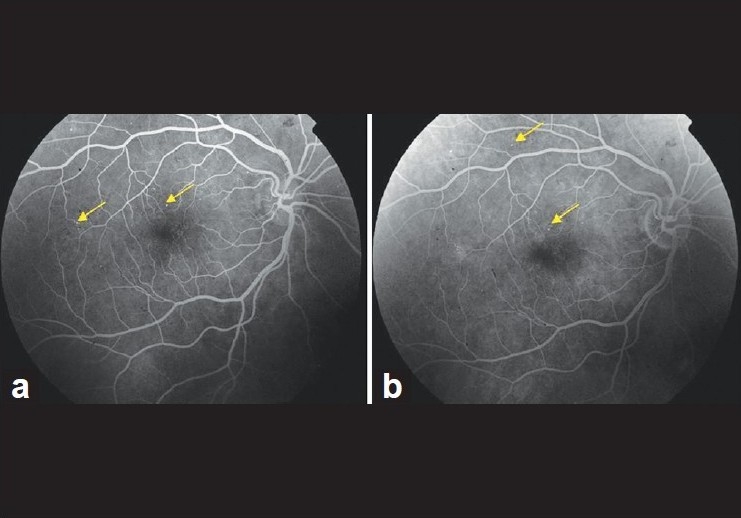

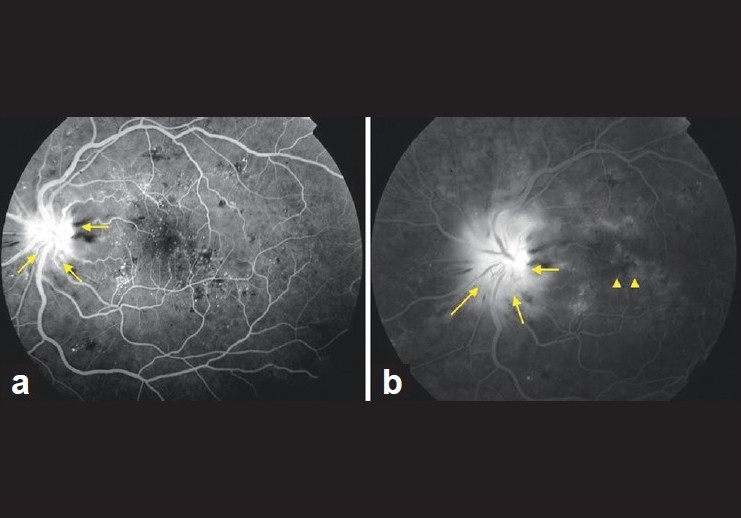

Figure 5.

OD early (a) and late phase (b) FFA shows no macular leak; arrows: microaneurysms

Figure 6.

OS FFA: early phase (a) and late phase (b); arrows: leaking optic disc; arrow heads: macular leak

Three weeks after the initial presentation, the patient received an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (1.25 mg in 0.05 ml) OS. After 18 days, visual acuity OS improved to 6/15 and the disc swelling was less. One month postinjection, his visual acuity improved to 6/6 and focal laser photocoagulation was applied to the macula OS for the remaining edema as this treatment is standard and has a permanent effect rather than temporary.

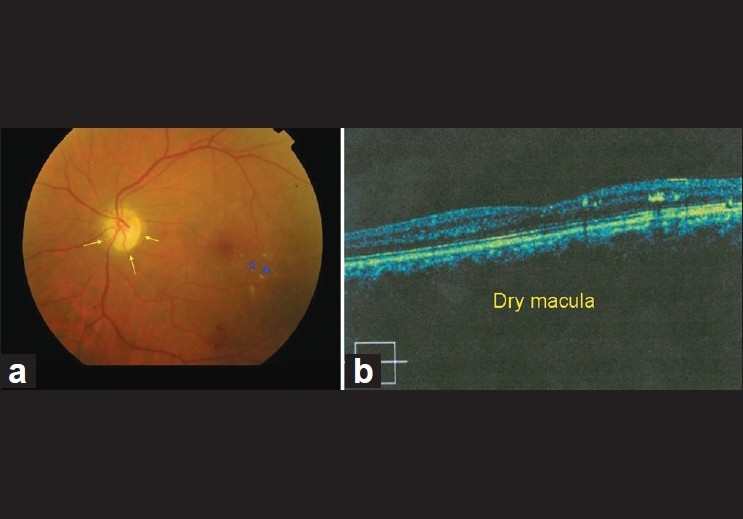

Five months postinjection, the patient remained with visual acuity of 6/6 OS with a cylinder correction of -1.75 ×70. The fundus examination OS revealed no disc swelling and the macula was dry. The most recent follow-up was 1 year postinjection, his visual acuity remained 6/6 in both eyes with normal IOP, and repeat OCT did not show macular edema OU [Figure 7]. However, the left optic disc was mildly pale.

Figure 7.

OS (1 year post-injection). (a) Shows fundus with pale disc (arrows) and hard exudates (stars). (b) Shows OCT OS

Discussion

Our case presented with an acute unilateral painless visual loss. Neuroimaging did not show any abnormalities. Absence of any ocular inflammatory signs ruled out inflammatory causes. A conclusion of diabetic papillopathy was made due to the following reasons: young age, uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, painless, presence of associated macular edema which is common in DP,[9] early disc hyperfluorescence on FFA, and good visual outcome posttreatment. Visual prognosis without treatment is also favorable in these cases, but it takes prolonged period of time to improve.[9]

Diabetic papillopathy is sometimes considered as a mild form of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION).[10] On the other hand, it is also considered as a distinctive disorder. Differences between both are as follows.[1] First, visual loss in AION is worse than in DP. Second, visual field defect in AION is usually persistent, in contrast to DP, in which visual field defects are transient. Third, visual improvement is limited in AION cases to only 30% of the patients, but in DP usually patients will have spontaneous and slow visual acuity improvement, and around 85% of the cases have final visual acuity of 20/50 or better.[9] Moreover, FFA may assist to differentiate between both conditions. In AION cases, FFA shows early disc hypofluorescence due to hypoperfusion with late leakage around the affected segment.[11] However, in DP cases the FFA shows a very early disc leakage that increases throughout the study. The early hyperfluorescence is most likely due to telangiectasia of the optic disc.[4] Finally, AION typically occurs in older patients, whereas DP occurs in younger ages.

The main indication of using anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VRGF), bevacizumab, in this case, was to treat the macular edema. Consequently, the patient had a rapid improvement of his vision postinjection along with resolution of the macular edema and disc swelling. The focal laser photocoagulation was added to the left macula as this is the standard treatment of diabetic macular edema and has a permanent effect.

The mechanism of action of bevacizumab on DP is not well understood. However, the good response to the treatment may suggest that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of this condition. Further studies are required to explore the role of VEGF in the pathogenesis of DP. As mentioned earlier, periocular corticosteroid was found also to be effective in accelerating improvement of DP.[8] This suggests inflammatory elements could be involved in pathogenesis of this disorder. Recently reported, AION can present as an adverse effect of anti-VEGF.[12]

The patient in this case report will need close follow-ups as progression of diabetic retinopathy and/or recurrence of DME are possible. He will need also a documentation of his visual field, which was not obtained previously.

Conclusion

This case showed that anti-VEGF (such as bevacizumab) is a useful treatment in diabetic papillopathy by shortening the duration of the course of the disease. In addition, diabetic macular edema responds well to anti-VEGF therapy, and this positive outcome strongly supports results of previous studies on treatment of diabetic macular edema with these agents.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bayraktar Z, Alacali N, Bayraktar S. Diabetic papillopathy in type II diabetic patients. Retina. 2002;22:752–8. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostri C, Lund-Anderson H, Sander B, Hvidt-Nielsen D, Larsen M. Bilateral diabetic papillopathy and metabolic control. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2214–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: Clinical characteristics in diabetic patients versus nondiabetic patients. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1818–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaphiades MS. The disk edema dilemma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:183–8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Haddad CE, Jurdi FA, Bashshur ZF. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for the management of diabetic papillopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:1151–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ornek K, Oğurel T. Intravitreal bevacizumab for diabetic papillopathy. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26:217–8. doi: 10.1089/jop.2009.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Dhibi H, Khan AO. Response of diabetic papillopathy to intravitreal bevacizumab. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18:243–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.84056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansour AM, El-Dairi MA, Shehab MA, Shahin HK, Shaaban JA, Antonios SR. Periocular corticosteroids in diabetic papillopathy. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:45–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regillo CD, Brown GC, Savino PJ, Byrnes GA, Benson WE, Tasman WS, et al. Diabetic papillopathy: Patient characteristics and fundus findings. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:889–95. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100070063026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkins EJ, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Treatment of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oto S, Yilmaz G, Cakmakci A, Aydin P. Indocyanine green and fluorescein angiography in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Retina. 2002;22:187–91. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodla A, Rao P. Non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy followed by intravitreal bevacizumab injection: Is there an association? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:349–50. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.64142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]