Abstract

Art through the ages has been a marker of societal trends and fashion. Obesity is proscribed by physicians and almost reviled by today's society. While Venus (Aphrodite) continues to be the role model for those to aspire to free themselves from the clutches of obesity, Paleolithic humans had a different view of the perfect female form. Whether the Venus of Willendorf was a fashion symbol will be never answered, but the fact is that she remains testimony to the fact that obesity has been with us for several millennia.

Keywords: Infertility, metabolic syndrome, obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome, Venus de Milo, Venus of Willendorf

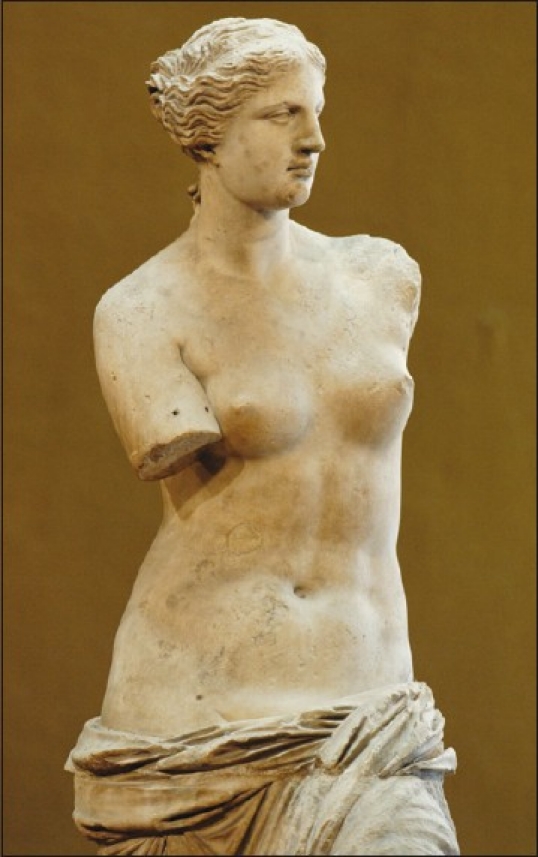

Human kind's obsession with body fat is not new. The current obsession is several millennia in the making. When present in the right proportions in the female form, it has been a symbol of feminity, sensuality and importantly (for our ancestors) fertility. The most famous exapmle is in permanent display at the Louvre in Paris – the Venus de Milo [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Venus de Milo

Venus (to the Romans), attributed to represent Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, is a sculpture purportedly carved in marble by Alexander of Antioch. It is 6’3”, shapely with missing arms and legs but has inspired artists and connoisseurs alike for centuries to create the perfect blend that depicts beauty and fertility.[1] As a modern age tribute, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, until recently, had Venus on their logo.[2]

But Venus is not the first female figure in human history and certainly not the first one to represent beauty and love. It appears that early humans had their own view on the perfect female form; they subscribed to neither Antioch's nor, for that matter, Armani's idea of the perfect form.

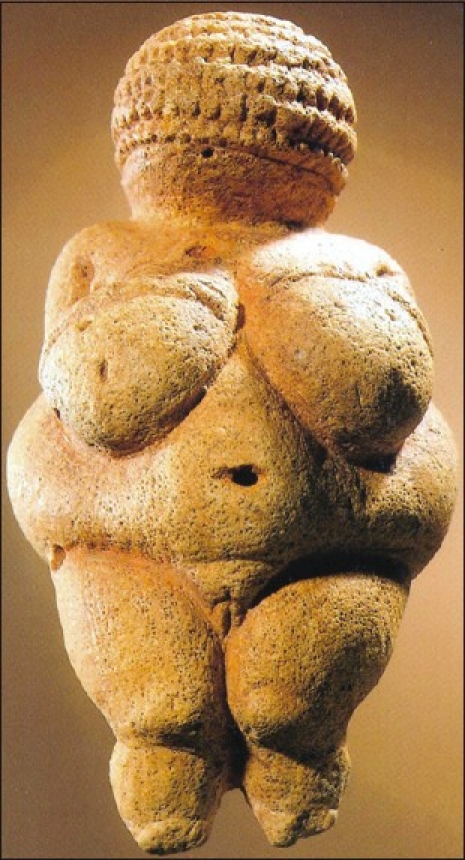

The most famous early image of a human, that of a woman, is the oolitic limestone representation found by the archeologist Josef Szombathy in an Aurignacian deposit in a terrace, 30 m above the Danube River near the town Willendorf in Austria. The 11.1 cm statue dates back to c. 24,000–22,000 BCE. Her great age and pronounced female form (see below) quickly established the Venus of Willendorf as an icon of prehistoric art[3] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The woman of Willendorf

The sculpture shows a woman with a large stomach that overhangs but does not hide her pubic area. A roll of fat extends around her middle, joining with large but flat buttocks. Her thighs are also large and pressed together down on the knees. Her forearms are, however, thin and holding the upper part of her large and full breasts. The genital area is deliberately emphasized with the vulva well detailed. At the time of its discovery, the statuette showed traces of red ocher pigment, which has been thought to symbolize, or serve as a surrogate of, the menstrual blood. This with the breasts and the rounded stomach accentuate the notion of procreativity and nurture.

The term “Venus” was jokingly, if not satirically, affixed to her, but it has stuck. The woman from Willendorf is just one, but certainly the most famous of a number of “Venus figurines” from the upper Paleolithic era (40,000 BCE onward). Other Venuses from the same era, like the Venus of Hohle Fels, all share the same features.

To the modern day endocrinologist, the Willendorf Venus is an icon of obesity and metabolic syndrome.[4] Some have speculated that Venus also had polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and was not probably fertile herself. An alternate hypothesis is that in the hunter–gatherer society that she lived in, lower BMI was more common in women with consequent infertility;[5] “adding fat” and aspiring to become if not becoming Willendorfian was therefore de sirable. Venus, therefore, could be a model for hunter-gatherer womento aspire for, with no chances of ever become one.

We will never know for sure why Venus was built – the fact that this obese great grandmother of all of us succeeded in improving fertility is evident when you look around. Several millennia after she was made, her proportions do not evoke the admiration that she probably inspired in the Paleolithic man. It is doubtful that even her descendant, the Venus of Milo, will be a style statement today (although she does appear healthy and even has the beginning of a six pack). Since 1959, every girl child has grown up with a figurine of Barbie (Millicent Roberts) – now 52, but in every way, a Venusian icon. If Barbie were real, she would have a waist of 18” and would probably topple over because of the enormity of her upper torso.[6]

For the all the right reasons, physicians eschew obesity; society has taken it the other extreme in some ways – promoting size zeros. For some of us who have trouble losing weight, looking at the overweight style icons in the paintings of Rubens or reflecting on the stature of Venus of Willendorf does provide some comfort.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davidson G. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2003. Disarmed: The story of the Venus de Milo. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haiken E. Johns Hopkins Press; 1997. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct]. Venus Envy: A history of cosmetic surgery. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/h/haiken-venus.html . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witcombe CL. The Venus of Willendorf. [Last accessed in 2011 Oct]. Available from: http://arthistoryresources.net/willendorf/willendorfdiscovery.html .

- 4.Bray GA. Obesity, a disorder of nutrient partitioning: The MONA LISA hypothesis. J Nutr. 1991;121:1146–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.8.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colman E. Obesity in the Paleolithic era. Endocr Pract. 1998;4:58–9. doi: 10.4158/EP.4.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winterman D. What would a real life Barbie look like? 2009. Mar 6, [Last accessed on 2011 Oct]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/7920962.stm .