Abstract

China is experiencing a rapid increase in the incidence of HIV infections, which it is addressing proactively with broad implementation of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Within a cultural context extolling familial responsibility, family caregiving may be an important component to promote medication adherence for persons living with HIV in China. Based on 20 qualitative interviews with persons living with HIV and their family caregivers and a cross-sectional survey with 113 adults receiving HIV care at Beijing's Ditan outpatient clinic, this mixed-methods study examines family caregivers' role in promoting adherence to ART. Building upon a conceptual model of adherence, this article explores the role of family members in supporting four key components enhancing adherence (i.e., access, knowledge, motivation, and proximal cue to action). Patients with family caregiving support report superior ART adherence. Also, gender (being female) and less time since ART initiation are significantly related to superior adherence. Since Chinese cultural values emphasize family care, future work on adherence promotion in China will want to consider the systematic incorporation of family members.

Introduction

In China, in 2009, an estimated 740,000 people (approximately 0.05% of the Chinese population) were living with HIV, with 49,845 deaths reported due to HIV complications.1 Without a concerted and comprehensive governmental prevention and intervention strategy, the number of HIV cases in China would likely rise dramatically.2 One fifth of the world's population resides in China; thus, the impact of an unchecked HIV epidemic could be staggering, with ripple effects worldwide.

In response to the HIV epidemic, the Chinese government initiated the “Four Free and One Care” policy, which aims to provide free antiretroviral treatment (ART) for rural and urban persons living with HIV with financial difficulties; free voluntary HIV antibody testing, HIV testing of newborns, and HIV testing and counseling for pregnant women; free schooling for children orphaned by HIV; and, care and economic assistance to the households of persons living with HIV.3,4 Since China's HIV epidemic has largely affected socially marginalized populations (e.g., poor rural farmers and injection drug users), stigma, discrimination and lack of financial resources continue to present serious structural barriers to accessing HIV care,5 including ART.6–8

In contrast to the more individualistic orientation characteristic of the West, traditional values in Chinese society rely on interpersonal and dyadic relations as the basis of social status.9 Such relations are ritualistic and formal, and individuals rarely make decisions without first considering the impact on family.10–12 Given the pivotal position of family in Chinese society and the severe physical, emotional, and social challenges facing people living with HIV, it is critical that we begin to understand the caregiving assistance provided to HIV patients and the impact of such care on adherence to ART. Furthermore, since part of China's HIV epidemic is concentrated in rural areas with limited access to formal health care providers, family caregivers may be the only resource available to provide needed assistance, including ART adherence support.

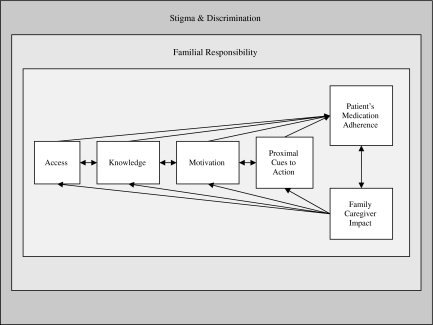

In an earlier article, we described the development and testing of a conceptual model of the factors related to ART adherence in China.5 The primary components of the model included access to medications and treatment regimens (a structural component); accurate knowledge about the medications such as dosing and potential side effects (a cognitive component); motivation to adhere to the medications (a psychological component); and, an internal or external proximal cue to take the medication (a social/electronic component).5 Based on the findings in this mixed methods research, we extend our original conceptual model to more fully incorporate the important influence of family within Chinese culture and the larger social environment (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model to guide integration of family members and caregivers in medication adherence interventions.

Based on qualitative interviews with persons living with HIV and their family caregivers and a cross-sectional survey with persons receiving HIV care at the outpatient clinic of Beijing's Ditan Hospital, a national referral infectious disease hospital, this mixed-methods study examines family members' role in promoting adherence to ART. We begin with an analysis of the qualitative data that explores the role of family caregivers in supporting the four key components enhancing adherence (i.e., access, knowledge, motivation and proximal cue to action). Next, we examine the survey data to investigate whether family caregiving support promotes superior adherence, after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. Considered together, data from both sources provide insight into how family members support medication-taking behaviors and suggest potential ways to effectively integrate family caregivers into intervention efforts to promote adherence.

Methods

The overall research was designed to examine barriers and facilitators to ART adherence and to inform the development and evaluation of a nurse-delivered intervention in a preliminary randomized controlled trial to support and enhance long-term ART use, through the potential use of electronic reminders and/or counseling, either individually or with a treatment adherence partner.13 This project was conducted through an on-going collaboration among U.S. and Chinese investigators at the University of Washington, China Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and Ditan Hospital.

The data were collected at Ditan, which is regarded as one of the premier specialist hospitals for HIV care in Beijing, China. For both phases of the research, six physicians and one senior nurse working at the Ditan HIV unit recruited potential participants from both the inpatient and outpatient wards during a hospitalization or routine care visit. The clinicians informed patients about the study and referred them to research personnel for further information. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Ditan Hospital, China CDC, and the University of Washington. Study participants received a small monetary incentive of 150 RMB (∼US$20) for their time. The data presented in this article draw upon both qualitative and quantitative components of the research.

Qualitative component

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 20 persons affected by HIV, including patients living with HIV (n=10) and their family caregivers (n=10). A caregiver was defined as a family member or friend providing informal assistance and available to support the family member living with HIV. The semistructured interviews were conducted in Mandarin and addressed to what extent and how caregivers assist family members living with HIV and the barriers and facilitators encountered in supporting ART adherence. Interviewers used a guide to cover a range of topics, including what the caregiver knew about (a) the patient's treatment and side effect history with ART; (b) current medications and adherence behaviors; (c) knowledge of and instructions about medication taking, how the medications work, and the consequences of missed doses; (d) barriers and facilitators to adherence; and (e) any hopes or worries about the medications and their loved one. Each topic began with an open-ended question, such as “What kind of things do you do to help [patient] take his medications?” and was followed by more specific prompts to elicit greater detail. The qualitative interviews were conducted one-on-one between the interviewer and the patient living with HIV or the caregiver; patients and caregivers were interviewed separately since Chinese culture tends to discourage open discussion about a specific person when present. Interviewers, who received a 2-day training in qualitative techniques, included physicians, a nurse educator from Ditan Hospital and two of the study investigators. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

All transcripts were translated into English by four bilingual research staff and were then coded using Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development, 2005), using a mixture of top-down and bottom-up coding strategies based on our model. While the top-down coding strategy is driven by preexisting theory, the bottom-up coding strategy is driven by the additional information observed in the data.14 A particular strength of this interactive and reiterative application of the two approaches to qualitative data analysis is to attain balance between the requirement for analytic precision and flexibility for new patterns to emerge. The categorized data indicate the proportions of the participants expressing certain concepts and although these findings are by no means inferential, they are suggestive and provide insights for relative prevalence of concepts and directions for future research.15

Survey component

The survey component of the research involved face-to-face interviews with 70 patients initiating ART (who were subsequently enrolled in the intervention) and an additional 50 ART-experienced patients who were not involved in the intervention trial. While 120 patients completed the one-time 60-min interviewer-administered paper-and-pencil survey, 7 did not respond to the adherence questions, reducing the sample size available for analysis to 113.

The survey consisted of standardized measures to assess barriers and facilitators to ART adherence as well as physical and mental health status. Those measures not available in Mandarin were translated using standard translation and back-translation procedures.16 The survey also included questions that assessed the availability of family members to assist with HIV care and caregiving support provided as well as details about the patients' relationships with their caregivers, including frequency of contact, living arrangement, and type of care received. Adherence was assessed by using the Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ), a six-item patient self-report measure, which has shown strong reliability.17 In analyses, adherence was dichotomized (adherent or nonadherent), based on one of two assessment points depending on the patients experience with ART: at baseline for those who had been taking ART when enrolled in the study (ART-experienced) and at 25 weeks postintervention for those who were initiating ART (ART-naïve). Respondents were classified as nonadherent if they reported forgetting to take their medications; being careless in taking their medications; if they stopped taking their medications if they felt worse; if they missed doses in the past week; if they missed doses over the past weekend; or if they did not take any medications for one or more days over the past 3 months. If respondents answered affirmatively to any of the SMAQ items they were considered nonadherent.

Descriptive and bivariate statistics were used to examine the relation between adherence, family caregiving support, and background characteristics. The relation between adherence and family caregiving support was tested utilizing logistic regression, controlling for potential covariates. Variables were selected for the multivariate model based both on theoretical relevance and statistical significance in univariate models. Exposure to the study intervention was controlled in all analyses.

Qualitative Findings

Among the patients living with HIV that completed the semistructured interviews, the mean age was 37 years; 8 of the 10 patients were male and 7 had a high school education or less. The median time since receiving an HIV diagnosis was 1.5 years. All the patients living with HIV were on ART at the time of the interviews. Eleven caregivers completed the in-depth interviews. They had a mean age of 45 years; 9 were female and nearly all (9) were HIV negative. One caregiver was HIV positive and on ART at the time of the interview. Six of the caregivers had a high school education or less and most were employed, either working in manual labor (4) or professional/managerial positions (4); 2 of the caregivers were retired. In terms of the relationships between the caregivers and the patients living with HIV, 5 were spouses/partners, 3 were parents and their adult children, and 2 pairs were siblings. Seven of the caregivers lived with the patient. The participants in this study described several ways family caregiving supported or failed to support adherence, corresponding to the four components of the model (access, knowledge, motivation, and proximal cue to action).

Access

Providing financial support was the primary way that family caregivers promoted access to ART, as identified by both patients living with HIV (n=7) and their caregivers (n=8). Other ways that family caregivers supported access was through providing instrumental assistance (n=5), such as picking up medications and providing transportation to medical appointments. More than two thirds of the family caregivers (n=8) used their own salaries or other financial resources to cover the cost of medications, treatment and transportation, with three of the caregivers having money loaned to them to provide support. Although under the “Four Free, One Care” policy HIV medications are to be provided at no-cost, many of the patients (n=4) were ineligible due to their residency status or other factors. More than two thirds (n=8) of the caregivers shared that paying for treatment and/or medications created constant worry and severe economic hardship for them and their families. As one sister explained:

I could not fall asleep. I heard that the medications were very expensive. And I talked with my husband about selling our house to get the money. We did not have much savings, so selling the house was the only way out. (sister, age 42, caregiver of an ART-experienced younger sister)

This was echoed by the patients we interviewed. Seven of the ten persons living with HIV reported that they had gained financial support from their caregivers and family. A woman living with HIV described how her family had reassured her that they would buy her medications even if it exhausted their financial resources.

They were very worried, and didn't know what to do. They wondered how I could get it (HIV), and they tried their best to get treatment for me. They told me, even if they needed to sell the house or sell the car, they would get me the medications I needed.” (woman living with HIV, age 25, ART-naïve)

While the majority of caregivers were instrumental in supporting access to ART and other treatment options, stigma and shame limited ways that caregivers promoted access. Four of the caregivers shared that they would not use the patient's medical insurance or seek care from local health care providers because of stigma and the threat of disclosure, which seriously constrained the caregivers' capacity to support access to ART.

Knowledge

Accurate knowledge about dosing schedules, resistance, and potential side effects is necessary for accurate and consistent medication adherence. Four of the caregivers located information about medications and treatment and provided it directly to the family members living with HIV. For example, the wife of an ART-naïve patient comforted her husband, who had suffered from severe dizziness, by sharing information about the side effects of his medications.

My husband complains he has felt very dizzy recently. I told him that dizziness is a side effect of the medications. I told him that. I read the instructions and it says so. (wife, age 32, caregiver of an ART-naïve husband)

Four of those living with HIV confirmed receiving information from their family caregivers. An older male patient relied heavily on his caregiving daughter for information about his medications, including where to get them, and how and what to take.

I only went once to the clinic for testing. It was my daughter and her husband who went to the clinic, talked to the doctor, and got my medications. I only saw the doctor once. But my daughter has sorted out where I can get the medications in my county and what I should take. (man living with HIV, age 72, ART-naïve)

Despite their willingness to support adherence, the caregivers also shared their worries and concerns about HIV medications, including fears regarding their lack of effectiveness (n=5), drug resistance (n=5), and side effects (n=5). Three caregivers stated that their lack of knowledge and their own need for support presented barriers in helping their family members adhere to ART. In addition, two caregivers shared that their own limited educational level made it difficult to understand the medication's instructions and regimens. One mother who took care of her 32-year-old son shared she needed more information and help in order to better assist her son.

Now that my son is out of the hospital, I need more help from the service agencies. I'm just learning about HIV and I don't know much. I need more information and help to take good care of him. (mother, age 55, caregiver for an ART-naive son)

Motivation

Only two of the caregivers explicitly described how they used their relationship or influence to motivate their family member living with HIV to adhere to ART. As a caregiver living in a rural area explained:

My husband could not refuse to take the medicine. I told him we had been married for 50 years and lived in harmony, that he should not die first and leave me alone. I told him, “You must take the medicine for you and for me.” (wife, age 63, caregiver for an ART-naive husband)

However, 7 of 10 of the patients identified the support of their caregivers as enhancing their will to survive, which in turn promoted their ART adherence. This discrepancy between caregiver and patient reports may be due in large part to the tacit emotional bonds between caregivers and loved ones, largely unspoken but reinforced through daily interactions. This is exemplified in the following statement from a young man about how his parents' financial reassurance and support, although never expressed verbally, had strengthened his will to survive.

My parents made it clear to me that they would get me medications even if they needed to apply for loans. This really moved me. My family, especially my parents, did not and would not abandon me, and I am touched. Because they help support me, and did not push me away, I want to survive. If they had dumped me, I would have killed myself. Period. I think this is why I have survived. (male living with HIV, age 30, ART-naïve)

Proximal cue to action

The fourth component of the conceptual model is proximal cue to action, suggesting internal or external cues can be helpful to maintain consistent adherence. In general, the majority of persons living with HIV (n=10) and their caregivers (n=10) in this study felt confident about their ability to assess adherence and provide necessary support. The primary strategy that eight caregivers used to promote adherence was directly reminding the patient to take their medications. Two caregivers described how they directly administered the medications to their family member to insure adherence. In addition, one caregiver shared how she sought the support and assistance of other family members as a strategy to support ART adherence. A maternal caregiver living in northeastern China explained:

Some may not be able to take their medicine according to the instructions so they need someone to remind them. Even if the patient is fully capable of taking his medications by himself, he might still skip the medicine a couple times so he still needs monitoring. This can guarantee that the patient takes the medicine on time. (mother, age 55, caregiver for an ART-naive son)

In order to carry out this support strategy, the caregivers need to stay in close proximity with the family member living with HIV. A lack of close proximity, such as not living together, may substantively limit the caregivers' ability to remind the patients to take their ART. Two of the caregivers explained that not living with the HIV-infected family member presented a barrier to supporting adherence and made it difficult to remind or observe the patient taking their medications. This concern was also reiterated by two patients living with HIV. A 32-year-old male who worked as a business manager shared how the strategy of being reminded to take his medications by his caregiver failed when he was not at home.

I asked my parents to remind me to take my medications so I would not forget. However, when I am at work or go out of town for a business trip, this strategy doesn't work at all. (man living with HIV, age 32, ART-naive)

Survey Findings

Family support and adherence

Table 1 describes the background characteristics of the patients who completed the survey; note they are demographically similar to participants in the qualitative interviews. More than two thirds (73%) of the patients reported having a caregiver who helped them with their HIV care. Primary caregivers were generally family members, mainly wives (36%) or mothers (28%) with whom they generally resided and had daily contact. Patients who were married or partnered (χ2=16.40), p<.001, with larger household size were [t(111)=−2.17], p<0.05, were more likely to receive family caregiving support.

Table 1.

Background Characteristics of 113 HIV-Positive Patients in China and Their Relationship to Family Caregiving Support, and Adherence

| |

|

Family caregiver support |

|

Adherenta |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes (n=83) | No (n=30) | p | Yes (n=54) | No (n=59) | p | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 36.7 (8.0) | 36.8 (7.6) | 36.2 (9.1) | 0.71 | 37.1 (7.9) | 36.3 (8.1) | 0.63 |

| Gender | 0.42 | 0.10 | |||||

| Male | 91 (80.5) | 65 (71.4) | 26 (28.6) | 40 (44.0) | 51 (56.0) | ||

| Female | 22 (19.5) | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | ||

| Ethnicity | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Han | 105 (92.9) | 77 (73.3) | 28 (26.7) | 50 (47.6) | 55 (52.4) | ||

| Other | 8 (7.1) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | ||

| Education | 0.65 | 0.85 | |||||

| High school or less | 68 (60.2) | 51 (75.0) | 17 (25.0) | 33 (48.5) | 35 (51.5) | ||

| Higher than high school | 45 (39.8) | 32 (71.1) | 13 (28.9) | 21 (46.7) | 24 (53.3) | ||

| Employed | 0.70 | 0.84 | |||||

| Yes | 58 (53.7) | 41 (70.7) | 17 (29.3) | 29 (50.0) | 29 (50.0) | ||

| No | 50 (46.3) | 37 (74.0) | 13 (26.0) | 24 (48.0) | 26 (52.0) | ||

| Religion | 0.98 | 0.14 | |||||

| Yes | 19 (16.8) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (63.2) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| No | 94 (83.2) | 69 (73.4) | 25 (26.6) | 42 (44.7) | 52 (55.3) | ||

| Residence | 0.86 | 0.03 | |||||

| Urban | 93 (82.3) | 68 (73.1) | 25 (26.9) | 14 (70.0) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| Rural | 20 (17.7) | 15 (75.0) | 5 (25.0) | 40 (43.0) | 53 (57.0) | ||

| Relationship | 0.00 | 0.37 | |||||

| Married/partnered | 62 (54.9) | 55 (88.7) | 7 (11.3) | 32 (51.6) | 30 (48.4) | ||

| Other | 51 (45.1) | 28 (54.9) | 23 (45.1) | 22 (43.1) | 29 (56.9) | ||

| Household income | 0.69 | 0.64 | |||||

| <$2,000 | 66 (58.9) | 48 (72.7) | 18 (27.3) | 30 (45.4) | 36 (54.6) | ||

| $2,000+ | 46 (41.1) | 35 (76.1) | 11 (23.9) | 23 (50.0) | 23 (50.0) | ||

| Household size | Mean (SD) 2.4 (2.2) | Mean (SD) 2.7 (2.3) | 1.6 (2.0) | 0.03 | Mean (SD) 2.4 (1.6) | Mean (SD) 2.3 (2.7) | 0.84 |

| Time since ART initiation (weeks) | 13.8 (8.8) | 13.7 (9.0) | 14.2 (8.5) | 0.80 | 11.8 (3.4) | 15.7 (11.5) | 0.02 |

Adherent=adherent in taking HIV medications.

Note: χ2 tests, Fisher's exact tests, and t tests were conducted. Missing cases were excluded from the analyses.

SD, standard deviation; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Forty-eight percent of the patients reported being adherent in taking their HIV medications. Those who were adherent reported less time since initiating HIV medication [t(111)=2.41], p<.05, and were more likely to be living in an urban environment (χ2=4.81), p<0.05. Also, they were more likely to have a caregiver who helped them with their HIV care (χ2=5.18), p<0.05.

We examined whether family caregiving support remained a significant predictor of adherence, after controlling for potential covariates, including age, education, gender, urban residence, relationship status, household size, length of time on HIV medication, and the intervention. As shown in Table 2, those having family caregiving support were significantly more likely to be adherent with ART than those without family caregiving support even after controlling for the potential covariates. Superior adherence also was related to being female (versus male) and more recently initiating ART.

Table 2.

Predictors of ART Adherence Among 113 HIV-Positive Patients in China

| Variable | AOR | (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | (0.03) | 0.49 |

| Gender | 3.49 | (2.15) | 0.04 |

| Education | 1.46 | (0.78) | 0.48 |

| Household income | 1.63 | (0.82) | 0.33 |

| Urban residence | 0.36 | (0.24) | 0.12 |

| Married/partnered | 0.60 | (0.32) | 0.34 |

| Household size | 0.98 | (0.11) | 0.84 |

| Time since ART initiation | 0.92 | (0.03) | 0.02 |

| Adherence intervention | 4.24 | (2.15) | 0.004 |

| Family caregiver support | 3.75 | (2.21) | 0.03 |

Likelihood ratio χ2 (10)=30.73, p<0.001.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Discussion

Patients in this study with family caregiving support reported superior ART adherence. In accordance with the refined conceptual model presented, the family caregivers were instrumental in supporting key components to enhance adherence, including access, knowledge, motivation and proximal cue to action. While previous studies have examined the influence of peer support on ART adherence,18,19 this is one of the first studies to investigate the extent to which familial helpers promote adherence. Furthermore, the findings underscore the importance of extending adherence theories to more fully incorporate the important influence of family within Chinese culture and the larger social environment.

Our conceptual model illustrates how family care intersects with the social context as an important influence on ART adherence in China. It is imperative that adherence theories be grounded in the sociocultural context and tailored to represent the specific dynamics of both the population and culture to fully capture the complexities of relevant barriers and facilitators impacting adherence in resource-limited settings.20 In these environments, family and community members are often the only feasible option to promote adherence to treatment or provide other needed forms of support.21–23 The family caregivers in this study were in a key position to support ART adherence because of proximity (they most often lived within the same household and had daily contact), intimate knowledge of the patient, and ability to negotiate with other family members to support adherence.

The research findings reported here suggest multiple intervention points for family caregivers to serve as treatment partners within each of the key components of the conceptual model. They are well positioned to support access (e.g., financially supporting the cost of therapy, locating free or affordable medications, and providing transportation to clinic visits); provide knowledge (attending clinic visits, obtaining up-to-date information about the medications and the disease, and understanding medication side effects); motivate the patient (encouraging family members, reminding them that they are valued and needed; letting them support other family members); and, provide proximal cue to action (reminding family members to take their medications, monitoring their regimens, assisting with pillboxes, setting up alarms and pagers, and helping with special instructions such as preparing meals when medications are to be taken with food).

While caregiver support may promote adherence, caregivers will need training and support to insure their helpfulness and effectiveness as treatment partners. Interventions are needed to assess and train family caregivers, as needed, so that they have the knowledge and skills necessary to perform such tasks as accurately administering medications regimens, managing side effects and providing emotional reassurance and support. It will also be important for caregivers to learn to recognize other potential risk factors that may impact adherence to ART (such as length of time since initiating ART) and to insure they don't engage in less helpful behaviors such as “nagging” the patient about their medications.24

Although family members are a crucial resource in HIV care, it is imperative that resources be made available to mitigate disruptions in HIV-affected households. While utilizing family caregivers may be an effective strategy to promote adherence, the deleterious impacts of providing care must be considered. High levels of stress often lead to caregivers' poor physical and mental health.25,26 Caregivers themselves require care and support and they too need help to reduce their financial hardship and emotional strain and worry about the future.

It is important to recognize that one third of the patients in this study did not have family caregivers to support ART adherence. In these cases, the patients may not have disclosed their HIV diagnosis to their family or family relations may already be strained. Due to severe HIV stigma in China patients may also be at risk of isolation and rejection from their family,7,8 even if they are in dire need of family caregiving support. In such cases family support may not be feasible or desired.

While this study highlights the important role of HIV family caregivers in China, the research is preliminary and several limitations must be considered. First, the qualitative interviews were conducted with a relatively small number of patients and their family caregivers. Furthermore, many of the interviews were conducted by physicians that were actively treating the patients, which may have biased the participants toward reporting socially desirable experiences. In addition, the persons living with HIV who completed the survey were receiving treatment at a premier HIV hospital or clinic. As with other self-report measures of adherence, the measure used in this study may be biased by problems in recall and social desirability and result in the overestimation of adherence. Despite these limitations, this research offers important insights into the ways in which family members support ART adherence. Such information is needed to develop adherence interventions to support those living with HIV and their families.

While the Chinese government has implemented the “Four Free, One Care” policy to increase access to medications and treatment, structural barriers remain.3,5,27 Given the familial nature of Chinese society, limited access to formal care providers, and the need to develop culturally appropriate interventions, family caregivers are well positioned to promote ART adherence. Yet to be effective, intervention efforts must be tailored to the specific cultural dynamics, with strategies developed to assist HIV affected families.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by MH074364 and MH074364-S1 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Simoni, PI). We acknowledge Bu Huang for her assistance in obtaining funding for the project, and Wei Qu for coordinating the study onsite.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.CWS. China lifts ban barring entry to foreigners with HIV and AIDS. 2010. www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/asiapcf/04/27/china.aids/index.html. [Jan 3;2011 ]. www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/asiapcf/04/27/china.aids/index.html

- 2.UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI. 2008. www.unaids.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/China.asp. [Dec 11;2010 ]. www.unaids.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/China.asp

- 3.Zhang F. Dou Z. Ma Y, et al. Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:241–251. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00006. W-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F. Haberer JE. Wang Y, et al. The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: Challenges and responses. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S143–148. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304710.10036.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starks H. Simoni J. Zhao H, et al. Conceptualizing antiretroviral adherence in Beijing, China. AIDS Care. 2008;20:607–614. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X. Wu Z. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV/AIDS patients in rural China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S149–155. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304711.87164.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao-Ru Z. Hong Y. Xiao-Hong L, et al. The personal experiences of HIV/AIDS patients in rural areas of western China. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:447–453. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L. Wu Z. Wu S. Zhaoc Y. Jia M. Yan Z. HIV-related stigma in health care settings: A survey of service providers in China. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21:753–762. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang KS. Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. In: Lin T, editor; Tseng W, editor; Yeh E, editor. Chinese Societies and Mental Health. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L. Sun S. Wu Z. Wu S. Lin C. Yan Z. Disclosure of HIV Status is a family matter: Field notes from China. J Family Psychol. 2007;21:307. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L. Wu S. Wu Z. Sun S. Cui H. Jia M. Understanding family support for people living with HIV/AIDS in Yunnan, China. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:509–517. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhan HJ. Chinese caregiving burden and the future burden of elder care in life-course perspective. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2002;54:267–290. doi: 10.2190/GYRF-84VC-JKCK-W0MU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoni JM. Chen WT. Huh D, et al. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of a nurse-delivered medication adherence intervention among HIV-positive outpatients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Beijing, China. AIDS Behav. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chi MTH. Quantifying qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. J Learning Sci. 1997;6:271–315. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandelowski M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:230–240. doi: 10.1002/nur.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rankin SH. Galbraith ME. Johnson S. Reliability and validity data for a Chinese translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression. Psychol Rep. 1993;73(3 Pt 2):1291–1298. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.73.3f.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knobel H. Alonso J. Casado JL, et al. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: The GEEMA study. AIDS. 2002;16:605–613. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simoni J. Huh D. Frick PA, et al. An RCT of peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral therapy adherence and clinical outcomes among adults initiating or modifying therapy in Seattle, WA, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:465–473. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181b9300c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoni JM. Pantalone DW. Plummer MD. Huang B. A randomized controlled trial of a peer support intervention targeting antiretroviral medication adherence and depressive symptomatology in HIV-positive men and women. Health Psychol. 2007;26:488–495. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware NC. Wyatt MA. Bangsberg DR. Examining theoretic models of adherence for validity in resource limited settings. J AIDS. 2006;43:18–22. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248343.13062.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdool-Karim SS. Durban 2000 to Toronto 2006: The evolving challenges to implementing AIDS treatment in Africa. AIDS. 2006;20:N7–N9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247110.51338.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro A. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment: Merging the clinical and social course of AIDS. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knodel J. Saengtienchai C. Older-aged parents: The final aafety net for adult sons and daughters with AIDS in Thailand. J Family Issues. 2005;26:665–698. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wrubel J. Stumbo S. Johnson MO. Male same-sex couples dynamics and received social support for HIV medication adherence. J Soc Pers Relat. 2010;27:553–572. doi: 10.1177/0265407510364870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredriksen-Goldsen K. Scharlah AE. Families and Work: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulz R. O'Brien AT. Bookwala J. Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence correlates and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu J. Sullivan SG. Dou Z. Wu Z. Economic stress and HIV-associated health care utilization in a rural region of China: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21:787–798. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]