Abstract

Studies of retroviruses have been instrumental in revealing the existence of an array of antiviral proteins, or restriction factors, and the mechanisms by which they function. Some restriction factors appear to specifically inhibit retrovirus replication, while others have a broader antiviral action. Here, we briefly review current understanding of the mechanisms by which several such proteins exert antiviral activity. We also discuss how retroviruses have evolved to evade or antagonize antiviral proteins, including through the action of viral accessory proteins. Restriction factors, their viral targets and antagonists have exerted evolutionary pressure on each other, resulting in specialization and barriers to cross-species transmission. Potentially, this recently revealed intrinsic system of antiviral immunity might be mobilized for therapeutic benefit.

Introduction

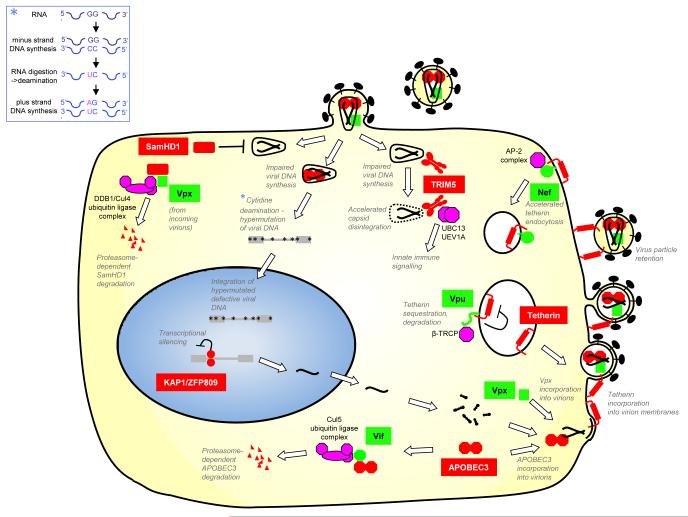

Although direct antiviral mediators are known or suspected to exist for a variety of viral families, a significant impetus for the study of such proteins has come from recent discoveries made in the field of retrovirology. Most modern retroviruses are specialists, having adapted to colonize a single or narrow range of host species and/or cell types, and for many years, this host range was thought to be determined primarily by their ability (or inability) to parasitize the particular variants of required molecules (e.g. receptors) that are present in a candidate host cell type or species. Indeed, it was almost completely unappreciated that viruses have driven the evolution of defense mechanisms that directly inhibit specific processes in the retrovirus life cycle. In recent years, this view has changed, and we now know of several specific antiretroviral proteins encoded by host cells (Figure 1), and we have come to appreciate that variation in host defenses is a critical determinant of host range. The study of known antiretroviral defenses is currently one of the most vibrant areas of virology, particularly since some defense mechanisms have broader activity, and target a variety of virus families.

Figure. Factors and events in the restriction of retroviral replication by host proteins.

Key retroviral restriction factors are shown in red, antagonists expressed by the HIV/SIV retroviruses are shown in green. Cellular cofactors, co-opted by viral antagonists are shown in purple. Key events or processes in the restriction of retroviral replication or associated with the action of the antagonists are indicated. The process of APOBEC3-mediated hypermutation is depicted in detail in the inset panel.

While several antiretroviral gene products have arisen and evolved independently, and have nothing in common in the mechanisms by which they function, they often share some key features. First, they are encoded by functionally autonomous, individual genes and inhibit retrovirus replication in cell culture. Second, some are type-I interferon (IFNα/β) stimulated genes (ISGs) in at least some cell types. Third, retroviruses are often found to have evolved to resist the action of antiretroviral proteins in their natural host species, sometimes (e.g. in the HIV/SIV group of retroviruses) by encoding accessory genes that antagonize the inhibitor’s function. Fourth, the sequence of antiretroviral genes tend to be unusually variable in primates, and have evolved via diversifying selection - i.e. they exhibit high dN/dS ratios over at least a portion of their coding sequence. The unusually high variability in antiretroviral genes means that retroviruses are often adapted to evade particular variants of these proteins that are present in their natural hosts, and barriers to cross species transmission are thus imposed. Fifth, antiretroviral proteins tend to function in unanticipated, unique and interesting ways. Here, we review our current understanding of several of the presently known antiretroviral proteins.

APOBEC3 proteins

A key cellular antiretroviral factor is Apolipoprotein B editing catalytic subunit-like 3G (APOBEC3G)[1]. This is a member of a family of enzymes with cytidine deaminase activity whose number has expanded during mammalian evolution to 7 members that are well conserved in primates[2,3]. In addition to APOBEC3G, other members of the family, including APOBEC3F and 3H, are active against retroviruses, whereas others inhibit retrotransposons and some even target viruses from other families (reviewed in[4]). APOBEC3 proteins inhibit virus infectivity by an unusual mechanism. The proteins themselves are incorporated into retroviral particles via interaction with RNA[5-7]. While, intuitively, it seems likely that some specific interaction with viral RNA drives APOBEC3 incorporation (since viral RNA represents only a small percentage of the total RNA in the cell cytoplasm), APOBEC3 proteins are incorporated into retroviruses whose sequence is highly divergent. Upon infection of a new target cell, the viral capsid core, which contains APOBEC3 as well as viral components, is released into the target cell cytoplasm. Thereafter, reverse transcription and digestion of the viral RNA results in the single minus-strand DNA intermediate that becomes a target for APOBEC3 catalyzed deamination [8-11]. The viral genome thus becomes ‘poisoned’ with G-to-A mutations that inactivate the virus (Figure1). Additionally, it has been suggested that APOBEC3 proteins inhibit virus infectivity via an unknown mechanism that is independent of enzymatic activity[12]. This, might be a consequence APOBEC3 binding to viral RNA, which could interfere with reverse trancription.

The weapon chosen by lentiviruses to combat APOBEC3 inhibition is a small viral protein named Vif[1]. Vif proteins block APOBEC3 protein incorporation into virions by reducing the overall levels of APOBEC3 proteins in the virus-producing cell (Figure 1). This is achieved by simultaneous interaction of Vif with APOBEC3 proteins and the Cul5 and elongin B and C proteins, causing APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation in the proteasome[8,13-16]. The adaptation of various lentiviruses to their host species is reflected in the specificity with which the Vif protein from a particular lentivirus antagonizes the APOBEC3 proteins expressed in its host. Thus, HIV-1 Vif protein is very efficient in targeting human APOBEC3 proteins but has no activity against proteins from lower primates[17,18]. Conversely, some Vif proteins are active against APOBEC3 proteins from a wider range of hosts; For example, Vif proteins from the SIVsm lineage have a broad ability to antagonize APOBEC3G from non-natural host species, perhaps providing an explanation for why this lineage of viruses (originally derived from sooty mangabeys) has been able to colonize both human and macaques.

TRIM5/TRIMCyp proteins

A second intrinsic antiretroviral defense mechanism is TRIM5α[19], a member of the tripartite motif protein family that derive their name from the presence of three characteristic protein domains at their N-terminus, namely RING, B-Box and coiled coil domains. The C-terminus of TRIM proteins is very heterogeneous and, in the case of TRIM5α, is a SPRY/B30.2 domain. This C-terminal domain recognizes and binds to the incoming viral capsid that forms the shell surrounding the viral enzymes and nucleic acids[20,21]. Thus, the avoidance of inhibition by TRIM5α in a given host species requires the selection of capsid protein sequences or structures that are not recognized by TRIM5. As such, the HIV-1 capsid has evolved to avoid detection by human TRIM5α, but is sensitive to TRIM5α inhibition from some other species such as rhesus macaques[19,22-25]. In certain species (e.g. Owl monkeys and some macaques) the TRIM5 C-terminal SPRY domain has been replaced by cyclophilin A (CypA) following LINE-mediated retrotransposition of CypA-coding sequences into the TRIM5 locus[26-32]. Due to the ability of CypA to interact with HIV-1 and other lentiviral capsids, the resulting TRIMCyp fusion proteins are generally strong inhibitors of HIV-1 infectivity. Surpisingly, the TRIMCyp protein in macaques has acquired mutations in the CypA-coding region that render it incapable of binding the HIV-1 capsid, although it inhibits infection mediated by other CypA-binding lentiviral capsids such as HIV-2, FIV and SIVagmTan[31,32]. Interestingly, chimeric viruses expressing capsid proteins from ‘fossilized’ lentiviruses found in rabbits and gray mouse lemurs are also sensitive to inhibition by TRIMCyp proteins[33] suggesting that CypA binding by lentiviral capsids is an ancient phenomenon that was exploited by hosts in the evolution of antiviral defenses. The mechanism by which infection is inhibited by TRIM5 proteins is not completely understood. It has been shown that the RING domain is required for full antiviral potency, but mutants lacking this domain can retain vestigial activity[34,35]. The RING domain has ubiquitin ligase activity and while blocking proteasome activity does not alleviate virus inhibition (suggesting that proteasomal-mediated degradation is not required for TRIM5 antiviral activity) it does change the precise step at which infection is blocked[36,37]. The coiled coil mediates TRIM5 dimerization and recently it has been shown that the B-box (with Arg121 in human TRIM5α playing a particularly important role) is important for formation of higher order multimers[38,39]. Interestingly, formation of higher order multimers enhances the antiviral activity of TRIM5[40]. In vitro, TRIM5 proteins can assemble into a hexagonal lattice[41] that is complementary to the hexagonal lattice assembled using the HIV-1 capsid protein and it is possible that assembly into this higher order structure facilitates capsid recognition or even the capsid disruption that accompanies inhibition by TRIM5 (Figure 1).

A very recent study[42] has suggested that TRIM5 has a second role in innate immune system signaling by acting together with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBC13-UEV1A to catalyze the formation of free K63-linked ubiquitin chains. These chains activate the TAK1 kinase complex, which in turn activates the AP-1 and NFκB pathways. Signaling is dependent on the ubiquitin ligase activity of TRIM5 and appears to be enhanced following infection with lentiviruses and, surprisingly, even vesicular stomatitis virus and Newcastle disease virus, two viruses that were not thought to interact with TRIM5[42]. The significance of this activity in the overall role of TRIM5 in inhibiting virus replication remains to be determined.

TRIM28/KAP1 and ZFP809

Although TRIM5 is the best studied of the TRIM proteins by virtue of its activity against HIV-1, it is by no means the only TRIM protein with direct antiviral or signaling activity. An intriguing cellular antiretroviral activity, particularly evident in embryonic stem cells, takes the form of a protein complex that includes the TRIM28/KAP1 protein[43]. Although exhibiting a broadly similar domain organization to TRIM5, TRIM28 acts completely differently. Specifically, it suppresses the transcription of retroviruses by recruiting a histone H3 K9 methyltransferase (ESET), a histone deacactylase (the NuRD complex) and heterochromatin associated protein (HP1). This repressive complex is specifically targeted to proviral DNA (Figure 1) via the tRNA primer binding site (PBS) sequence, and sequence-specific DNA binding activities associated with TRIM28. For one PBS sequence, namely Pro tRNA, a TRIM28-associated DNA binding protein (ZFP809) has been identified that binds the Pro tRNA sequence in proviral DNA and is required for provirus silencing[44]. Since TRIM28 also mediates silencing of proviruses with Lys1,2 tRNA PBS sequences[45], this finding strongly suggests the existence of alternative TRIM28 complexes with other associated DNA binding proteins that target different tRNA sequences. That this retroviral silencing activity is somewhat confined to embryonic cells suggests that it may have evolved to target endogenous retroviruses in particular. Consistent with this idea, endogenous retrovirus expression is dramatically upregulated in TRIM28-knockout murine embryos[46].

Tetherin

Another antiretroviral protein, tetherin[47,48], is an unusual type II transmembrane protein that has both a transmembrane anchor close to its N-terminus and a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) lipid anchor at its C-terminus. The bulk of the intervening extracellular domain forms a dimeric coiled-coil structure[49-51], with three extracellular cysteines forming disulfide bonds with corresponding cysteines in the tetherin dimer[52]. This configuration appears to allow tetherin to cause retention of nascent virions on cell surfaces through a direct tethering mechanism[52-54]. The aforementioned tetherin configuration is required for virion retention, but entire tetherin domains can be substituted with protein domains that have similar predicted structures but different amino acid sequences, with minimal impact on function[52]. Indeed, a synthetic tetherin-like protein, comprised of structurally similar but unrelated protein domains, can recapitulate tetherin’s activity[52]. These findings, and observations that tetherin can inhibit the release of virions of various virus families, whose proteins have no structural or sequence similarity[55-58], indicate that specific recognition events are likely dispensable for function. Rather, tetherin membrane anchors are efficiently incorporated into the lipid envelope of virion particles [52-54] and a likely scenario is that one pair of tetherin membrane anchors is incorporated into the lipid envelope of assembling particles, while the other remains in the plasma membrane of the infected cell. In this manner, the tetherin protein would span both virion and cell membranes after completion of budding. The extended conformation of the tetherin protein could serve to spatially separate the two pairs of membrane anchors, promoting their partition into virion and cell membranes as budding proceeds (Figure 1). An alternative possibility is that non-covalent interactions between tetherin dimers, some of which are incorporated into the virions promote adhesion of the nascent virion to the host cell membrane.

A variety of HIV and SIV proteins have been shown to posses tetherin antagonist activity[47,48,59,60]. The HIV-1 Vpu protein can be co-immunoprecipitated with tetherin [61] and causes its downregulation from the cell surface[48], by inhibiting its progress through the secretory pathway or by inducing its internalization[61-63]. Vpu can also reduce the overall steady state level of tetherin[64]. Most SIVs lack a Vpu protein and instead employ another accessory protein, Nef [59,60], that induces tetherin internalization from the cell surface by recruiting the AP2-clathrin adapter complex[65]. In a few instances, HIV/SIV Env proteins can also antagonize tetherin by sequestering it within intracellular compartments[66,67]. Tetherin antagonists found in HIVs and SIVs have clearly evolved to act in particular primate host species. Indeed, species-specific actions of Vpu and Nef have been used to determine that these two proteins target the tetherin transmembrane helices and cytoplasmic tail, respectively[59,60,68,69]. Analyses of Vpu and Nef proteins from many SIVs has revealed that these proteins effectively exchanged the role of tetherin antagonist as primate lentiviruses were passed from species to species and encountered tetherin proteins with different transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail sequences[70]. Most strikingly, SIVs found in chimpanzees (SIVcpz), employ the Nef protein as a tetherin antagonist, while their immediate descendent, HIV-1, employs Vpu. The acquisition of tetherin antagonist activity by HIV-1 Vpu almost certainly occurred because human tetherin harbors a deletion of 5 key residues in its cytoplasmic tail that are required for Nef sensitivity[59,60,70]. This and other gain of function events that accompanied primate lentivirus transmission to new species underscore the flexibility of function in HIV/SIV accessory proteins.

SAMHD1

Since the Vif, Vpu and Nef lentiviral accessory gene products have all been shown to antagonize restriction factors, the finding that Vpx recruits the Cul4 ubiquitin ligase complex by interacting with DDB1[71,72] immediately suggested that it was likely responsible for mediating the removal of an unidentified restriction factor. Interestingly, HIV-1 lacks a Vpx protein but other lentiviruses, including SIVMAC and HIV-2, express Vpx, which is very efficiently incorporated into viral particles. Vpx appears to alleviate an inhibition to the early steps of HIV/SIV infection in dendritic cells (DC) and macrophages[71,73,74]. This effect does not require Vpx expression in these target cells but rather delivery of this protein by incoming viral particles, consistent with the notion that Vpx counteracts a restriction factor. Very recent work has suggested that this factor is the SAM- and HD-domain containing protein 1 (SAMHD1)[75,76]. Mutations in SAMHD1 are associated with Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome, a genetic disorder that mimics congenital viral infection, and SAMHD1 expression is induced in DCs and macrophages in response to IFN γ. SAMHD1 fills all the required criteria to be the restriction factor targeted by Vpx[75,76] in that: 1) it is targeted for proteasomal degradation by Vpx and Cul4, 2) its overexpression in otherwise permissive cells renders them resistant to HIV-1 infection 3) RNAi mediated silencing of SAMHD1 expression in resistant cells increases permissivity to HIV-1 infection and alleviates the requirement for Vpx. Finally, mutations in the putative enzymatically active site of SAMHD1 abolish its antiviral activity[76].

Several questions remain regarding the importance of this factor in viral replication and, in particular, whether there are indeed differences in in vivo replication in DCs and macrophages between HIV-2 and SIVMAC (which both express Vpx) and HIV-1 (which does not).

Other antiretroviral proteins

Finally, several other cellular proteins have been shown to have antiviral activity although they have been less well studied. For example, the Zinc finger antiviral protein (ZAP), a CCCH-type ring finger protein, specifically inhibits accumulation of murine leukemia virus (MLV) mRNA in the cytoplasm of infected cells[77]. The protein is actually more potently active against alphaviruses, inhibiting translation of the viral mRNA[78]. It has also been shown that ZAP binds directly to specific sequences in the viral RNA providing a mechanistic explanation of its antiviral activity[79]. Another example consists of the fasciculation and elongation protein ζ-1 (FEZ1) that interacts with protein kinase C. Overexpressed Rat FEZ1 inhibits MLV and HIV-1 infection at a step after reverse transcription, but prior to nuclear entry[80]. Finally, the Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10) protein has a putative RNA helicase domain and colocalizes with APOBEC3G in P bodies[81]. Overexpression of MOV10 in retrovirus producing cells inhibits infectivity of various progeny retroviruses, including HIV-1, mainly by inhibiting reverse transcription once the virus enters target cells[82-84]. However, MOV10 silencing has minimal effects on retrovirus infectivity, and the precise mechanism by which it exerts its activity is yet to be elucidated. (Of note, MOV10 has also been suggested to be required for hepatitis D virus replication[85].)

Concluding remarks

The discovery and investigation of gene products with antiviral properties is one of the most exciting recent developments in virology. This review is, necessarily, not exhaustive, and new antiviral activities that target retroviruses and other virus families are being discovered with notable regularity. Understanding how the antiviral proteins work, how they have evolved, and how viruses escape them is providing new and unanticipated insights into the complexity of the interactions between viruses and their hosts. Ultimately, studies in this area may enable the use of pharmacological agents to mobilize these specific intrinsic defenses, or antagonize the viral antagonists, and thereby reduce the burden of viral disease in humans.

Highlights.

- Mammalian cells express a number or antiretroviral proteins, termed restriction factors

- Currently known antiretroviral restriction factors include APOBEC3, TRIM5, KAP1/TRIM28/ ZFP809, SAMHD1 and Tetherin

- These proteins have several unique and interesting ways of inhibiting viral replication

- Retroviruses evolve to evade or antagonize restriction factors, sometimes employing accessory proteins

- Restriction factors can impose barriers to cross-species viral transmission

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (PDB) and by grants from the National Institutes of health: R37AI64003 (PDB) and R01AI078788 and R21AI093255 (TH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature. 2002;418:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature00939. **Using complementary DNA substraction this paper first identified huAPOBEC3G (CEM15) as the protein that inhibits HIV-1 and is overcome by Vif. This is the first description of a cellular protein with specific activity against HIV-1 and marks the beginning of an explosion of interest in research on ‘restriction factors’.

- 2.Conticello SG, Thomas CJ, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Neuberger MS. Evolution of the AID/APOBEC family of polynucleotide (deoxy)cytidine deaminases. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:367–377. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyer SL, Emerman M, Malik HS. Ancient adaptive evolution of the primate antiviral DNA-editing enzyme APOBEC3G. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu YL, Greene WC. The APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases: an innate defensive network opposing exogenous retroviruses and endogenous retroelements. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090350. * In this compehensive review, Table 1 is especially useful as it summarizes the activity of various APOBEC3 viruses against exogenous and endogenous retroviruses and other viruses. See also reference #18.

- 5.Schafer A, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. Specific packaging of APOBEC3G into HIV-1 virions is mediated by the nucleocapsid domain of the gag polyprotein precursor. Virology. 2004;328:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svarovskaia ES, Xu H, Mbisa JL, Barr R, Gorelick RJ, Ono A, Freed EO, Hu WS, Pathak VK. Human apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme-catalytic polypeptide-like 3G (APOBEC3G) is incorporated into HIV-1 virions through interactions with viral and nonviral RNAs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35822–35828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zennou V, Perez-Caballero D, Gottlinger H, Bieniasz PD. APOBEC3G incorporation into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 2004;78:12058–12061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12058-12061.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris RS, Bishop KN, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Neuberger MS, Malim MH. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell. 2003;113:803–809. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature. 2003;424:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature01709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu Q, Konig R, Pillai S, Chiles K, Kearney M, Palmer S, Richman D, Coffin JM, Landau NR. Single-strand specificity of APOBEC3G accounts for minus-strand deamination of the HIV genome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:435–442. doi: 10.1038/nsmb758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H, Yang B, Pomerantz RJ, Zhang C, Arunachalam SC, Gao L. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature. 2003;424:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman EN, Holmes RK, Craig HM, Klein KC, Lingappa JR, Malim MH, Sheehy AM. Antiviral function of APOBEC3G can be dissociated from cytidine deaminase activity. Curr Biol. 2005;15:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marin M, Rose KM, Kozak SL, Kabat D. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1398–1403. doi: 10.1038/nm946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehle A, Strack B, Ancuta P, Zhang C, McPike M, Gabuzda D. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7792–7798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Malim MH. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat Med. 2003;9:1404–1407. doi: 10.1038/nm945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science. 2003;302:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1089591. *References 13-16 all describe the mechanism by which Vif antagonizes APOBEC3G by inducing its proteasomal degradation.

- 17.Mariani R, Chen D, Schrofelbauer B, Navarro F, Konig R, Bollman B, Munk C, Nymark-McMahon H, Landau NR. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell. 2003;114:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Virgen CA, Hatziioannou T. Antiretroviral activity and Vif sensitivity of rhesus macaque APOBEC3 proteins. J Virol. 2007;81:13932–13937. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01760-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. **Using a genetic screen, this paper is the first to identify TRIM5α as a potent inhibitor of retrovirus infection.

- 20.Sebastian S, Luban J. TRIM5alpha selectively binds a restriction-sensitive retroviral capsid. Retrovirology. 2005;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stremlau M, Perron M, Lee M, Li Y, Song B, Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Anderson DJ, Sundquist WI, Sodroski J. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatziioannou T, Perez-Caballero D, Yang A, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Retrovirus resistance factors Ref1 and Lv1 are species-specific variants of TRIM5alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10774–10779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402361101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keckesova Z, Ylinen LM, Towers GJ. The human and African green monkey TRIM5alpha genes encode Ref1 and Lv1 retroviral restriction factor activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10780–10785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402474101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perron MJ, Stremlau M, Song B, Ulm W, Mulligan RC, Sodroski J. TRIM5alpha mediates the postentry block to N-tropic murine leukemia viruses in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11827–11832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403364101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yap MW, Nisole S, Lynch C, Stoye JP. Trim5alpha protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10786–10791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402876101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nisole S, Lynch C, Stoye JP, Yap MW. A Trim5-cyclophilin A fusion protein found in owl monkey kidney cells can restrict HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13324–13328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404640101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, Luban J. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature. 2004;430:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02777. *This is the first paper to describe the expression and antiviral activity of a TRIMCyp fusion protein in Owl monkey cells.

- 28.Liao CH, Kuang YQ, Liu HL, Zheng YT, Su B. A novel fusion gene, TRIM5-Cyclophilin A in the pig-tailed macaque determines its susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S19–26. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304692.09143.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brennan G, Kozyrev Y, Hu S-L. TRIMCyp expression in Old World primates Macaca nemestrina and Macaca fascicularis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709511105. 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman RM, Hall L, Kirmaier A, Pozzi LA, Pery E, Farzan M, O’Neil SP, Johnson W. Evolution of a TRIM5-CypA splice isoform in old world monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virgen CV, Kratovac Z, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. Independent genesis of chimeric TRIM-cyclophilin proteins in two primate species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson SJ, Webb BLJ, Ylinen LMJ, Verschoor E, Heeney JL, Towers GJ. Independent evolution of an antiviral TRIMCyp in rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709003105. 10.1073/pnas.0709258105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstone DC, Yap MW, Robertson LE, Haire LF, Taylor WR, Katzourakis A, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. Structural and functional analysis of prehistoric lentiviruses uncovers an ancient molecular interface. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:248–259. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Stremlau M, Si Z, Sodroski J. The contribution of RING and B-box 2 domains to retroviral restriction mediated by monkey TRIM5alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26933–26940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Caballero D, Hatziioannou T, Yang A, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Human tripartite motif 5alpha domains responsible for retrovirus restriction activity and specificity. J Virol. 2005;79:8969–8978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8969-8978.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Caballero D, Hatziioannou T, Zhang F, Cowan S, Bieniasz PD. Restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by TRIM-CypA occurs with rapid kinetics and independently of cytoplasmic bodies, ubiquitin, and proteasome activity. J Virol. 2005;79:15567–15572. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15567-15572.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu X, Anderson JL, Campbell EM, Joseph AM, Hope TJ. Proteasome inhibitors uncouple rhesus TRIM5alpha restriction of HIV-1 reverse transcription and infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7465–7470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz-Griffero F, Qin XR, Hayashi F, Kigawa T, Finzi A, Sarnak Z, Lienlaf M, Yokoyama S, Sodroski J. A B-box 2 surface patch important for TRIM5alpha self-association, capsid binding avidity, and retrovirus restriction. J Virol. 2009;83:10737–10751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01307-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Javanbakht H, Yuan W, Yeung DF, Song B, Diaz-Griffero F, Li Y, Li X, Stremlau M, Sodroski J. Characterization of TRIM5alpha trimerization and its contribution to human immunodeficiency virus capsid binding. Virology. 2006;353:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Sodroski J. The TRIM5alpha B-box 2 domain promotes cooperative binding to the retroviral capsid by mediating higher-order self-association. J Virol. 2008;82:11495–11502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01548-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Chandrasekaran V, Pornillos O, Sodroski JG, Sundquist WI, Yeager M. Hexagonal assembly of a restricting TRIM5alpha protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:534–539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013426108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pertel T, Hausmann S, Morger D, Zuger S, Guerra J, Lascano J, Reinhard C, Santoni FA, Uchil PD, Chatel L, et al. TRIM5 is an innate immune sensor for the retrovirus capsid lattice. Nature. 2011;472:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature09976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolf D, Goff SP. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of murine leukemia virus in embryonic cells. Cell. 2007;131:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolf D, Goff SP. Embryonic stem cells use ZFP809 to silence retroviral DNAs. Nature. 2009;458:1201–1204. doi: 10.1038/nature07844. **References 43 and 44 are the key studies identifying the machinery responsible for proviral silencing in embryonic cells

- 45.Wolf D, Hug K, Goff SP. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of Lys1,2 tRNA-utilizing retroviruses in embryonic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12521–12526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805540105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowe HM, Jakobsson J, Mesnard D, Rougemont J, Reynard S, Aktas T, Maillard PV, Layard-Liesching H, Verp S, Marquis J, et al. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463:237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature08674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature. 2008;451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Damme N, Goff D, Katsura C, Jorgenson RL, Mitchell R, Johnson MC, Stephens EB, Guatelli J. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001. ** References 47 and 48 report the identification of tetherin as an antiviral protein, and the HIV-1 Vpu protein as an antagonist of tehterin activity.

- 49.Hinz A, Miguet N, Natrajan G, Usami Y, Yamanaka H, Renesto P, Hartlieb B, McCarthy AA, Simorre JP, Gottlinger H, et al. Structural basis of HIV-1 tethering to membranes by the BST-2/tetherin ectodomain. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang H, Wang J, Jia X, McNatt MW, Zang T, Pan B, Meng W, Wang HW, Bieniasz PD, Xiong Y. Structural insight into the mechanisms of enveloped virus tethering by tetherin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18428–18432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schubert HL, Zhai Q, Sandrin V, Eckert DM, Garcia-Maya M, Saul L, Sundquist WI, Steiner RA, Hill CP. Structural and functional studies on the extracellular domain of BST2/tetherin in reduced and oxidized conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:17951–17956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008206107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perez-Caballero D, Zang T, Ebrahimi A, McNatt MW, Gregory DA, Johnson MC, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits HIV-1 release by directly tethering virions to cells. Cell. 2009;139:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.039. *This paper contains a comprehensive anaysis of the mechanism by which tetherin causes virion retention.

- 53.Fitzpatrick K, Skasko M, Deerinck TJ, Crum J, Ellisman MH, Guatelli J. Direct restriction of virus release and incorporation of the interferon-induced protein BST-2 into HIV-1 particles. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000701. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hammonds J, Wang JJ, Yi H, Spearman P. Immunoelectron microscopic evidence for Tetherin/BST2 as the physical bridge between HIV-1 virions and the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000749. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jouvenet N, Neil SJ, Zhadina M, Zang T, Kratovac Z, Lee Y, McNatt M, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD. Broad-spectrum inhibition of retroviral and filoviral particle release by tetherin. J Virol. 2009;83:1837–1844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02211-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakuma T, Noda T, Urata S, Kawaoka Y, Yasuda J. Inhibition of Lassa and Marburg virus production by tetherin. J Virol. 2009;83:2382–2385. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01607-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaletsky RL, Francica JR, Agrawal-Gamse C, Bates P. Tetherin-mediated restriction of filovirus budding is antagonized by the Ebola glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2886–2891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811014106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pardieu C, Vigan R, Wilson SJ, Calvi A, Zang T, Bieniasz P, Kellam P, Towers GJ, Neil SJ. The RING-CH ligase K5 antagonizes restriction of KSHV and HIV-1 particle release by mediating ubiquitin-dependent endosomal degradation of tetherin. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000843. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang F, Wilson SJ, Landford WC, Virgen B, Gregory D, Johnson MC, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency viruses are tetherin antagonists. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jia B, Serra-Moreno R, Neidermyer W, Rahmberg A, Mackey J, Fofana IB, Johnson WE, Westmoreland S, Evans DT. Species-specific activity of SIV Nef and HIV-1 Vpu in overcoming restriction by tetherin/BST2. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000429. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000429. * References 59 an 50 are the first reports that Nef proteins are tetherin antagonists.

- 61.Dube M, Roy BB, Guiot-Guillain P, Binette J, Mercier J, Chiasson A, Cohen EA. Antagonism of tetherin restriction of HIV-1 release by Vpu involves binding and sequestration of the restriction factor in a perinuclear compartment. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lau D, Kwan W, Guatelli J. Role of the Endocytic Pathway in the Counteraction of BST-2 by Human Lentiviral Pathogens. J Virol. 2011;85:9834–9846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02633-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Skasko M, Tokarev A, Chen CC, Fischer WB, Pillai SK, Guatelli J. BST-2 is rapidly down-regulated from the cell surface by the HIV-1 protein Vpu: evidence for a post-ER mechanism of Vpu-action. Virology. 2011;411:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartee E, McCormack A, Fruh K. Quantitative membrane proteomics reveals new cellular targets of viral immune modulators. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang F, Landford WN, Ng M, McNatt MW, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. SIV Nef proteins recruit the AP-2 complex to antagonize Tetherin and facilitate virion release. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002039. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le Tortorec A, Neil SJ. Antagonism to and intracellular sequestration of human tetherin by the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 2009;83:11966–11978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01515-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gupta RK, Mlcochova P, Pelchen-Matthews A, Petit SJ, Mattiuzzo G, Pillay D, Takeuchi Y, Marsh M, Towers GJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein counteracts tetherin/BST-2/CD317 by intracellular sequestration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20889–20894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907075106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McNatt MW, Zang T, Hatziioannou T, Bartlett M, Fofana IB, Johnson WE, Neil SJ, Bieniasz PD. Species-specific activity of HIV-1 Vpu and positive selection of tetherin transmembrane domain variants. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000300. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gupta RK, Hue S, Schaller T, Verschoor E, Pillay D, Towers GJ. Mutation of a single residue renders human tetherin resistant to HIV-1 Vpu-mediated depletion. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000443. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sauter D, Schindler M, Specht A, Landford WN, Munch J, Kim KA, Votteler J, Schubert U, Bibollet-Ruche F, Keele BF, et al. Tetherin-driven adaptation of Vpu and Nef function and the evolution of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1 strains. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharova N, Wu Y, Zhu X, Stranska R, Kaushik R, Sharkey M, Stevenson M. Primate lentiviral Vpx commandeers DDB1 to counteract a macrophage restriction. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000057. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Srivastava S, Swanson SK, Manel N, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Lentiviral Vpx accessory factor targets VprBP/DCAF1 substrate adaptor for cullin 4 E3 ubiquitin ligase to enable macrophage infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000059. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goujon C, Riviere L, Jarrosson-Wuilleme L, Bernaud J, Rigal D, Darlix JL, Cimarelli A. SIVSM/HIV-2 Vpx proteins promote retroviral escape from a proteasome-dependent restriction pathway present in human dendritic cells. Retrovirology. 2007;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pertel T, Reinhard C, Luban J. Vpx rescues HIV-1 transduction of dendritic cells from the antiviral state established by type 1 interferon. Retrovirology. 2011;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Segeral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. ** References 75 and 80 report the identification of SAMHD1 as an antiviral protein that is removed by the action of Vpx

- 77.Gao G, Guo X, Goff SP. Inhibition of retroviral RNA production by ZAP, a CCCH-type zinc finger protein. Science. 2002;297:1703–1706. doi: 10.1126/science.1074276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bick MJ, Carroll JW, Gao G, Goff SP, Rice CM, MacDonald MR. Expression of the zinc-finger antiviral protein inhibits alphavirus replication. J Virol. 2003;77:11555–11562. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11555-11562.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guo X, Carroll JW, Macdonald MR, Goff SP, Gao G. The zinc finger antiviral protein directly binds to specific viral mRNAs through the CCCH zinc finger motifs. J Virol. 2004;78:12781–12787. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12781-12787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Naghavi MH, Hatziioannou T, Gao G, Goff SP. Overexpression of fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 (FEZ1) induces a post-entry block to retroviruses in cultured cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1105–1115. doi: 10.1101/gad.1290005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kozak SL, Marin M, Rose KM, Bystrom C, Kabat D. The anti-HIV-1 editing enzyme APOBEC3G binds HIV-1 RNA and messenger RNAs that shuttle between polysomes and stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29105–29119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Furtak V, Mulky A, Rawlings SA, Kozhaya L, Lee K, Kewalramani VN, Unutmaz D. Perturbation of the P-body component Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 infectivity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang X, Han Y, Dang Y, Fu W, Zhou T, Ptak RG, Zheng YH. Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10) protein inhibits retrovirus replication. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14346–14355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burdick R, Smith JL, Chaipan C, Friew Y, Chen J, Venkatachari NJ, Delviks-Frankenberry KA, Hu WS, Pathak VK. P body-associated protein Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 replication at multiple stages. J Virol. 2010;84:10241–10253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00585-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haussecker D, Cao D, Huang Y, Parameswaran P, Fire AZ, Kay MA. Capped small RNAs and MOV10 in human hepatitis delta virus replication. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:714–721. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]