Abstract

A study was undertaken between November 2008 and March 2010, in the focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis of Central Tunisia, to evaluate the role of Psammomys obesus (n=472) and Meriones shawi (n=167) as reservoir hosts for Leishmania major infection. Prevalence of L. major infection was 7% versus 5% for culture (p=not signifiant [NS]), 19% versus 16% for direct examination of smears (p=NS), and 20% versus 33% (p=NS) for Indirect Fluorescent Antibody Test among P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively. The peak of this infection was in winter and autumn and increased steadily with age for the both species of rodents. The clinical examination showed that depilation, hyper-pigmentation, ignition, and severe edema of the higher edge of the ears were the most frequent signs observed in the study sample (all signs combined: 47% for P. obesus versus 43% for M. shawi; p=NS). However, the lesions were bilateral and seem to be more destructive among M. shawi compared with P. obesus. Asymptomatic infection was ∼40% for both rodents. This study demonstrated that M. shawi plays an important role in the transmission and the emergence of Leishmania major cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia.

Key Words: Leishmania major, Meriones shawi, Psammomys obesus, reservoir host, Tunisia, zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis

Introduction

Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia is caused by Leishmania major MON-25 and transmitted by the vector Phlebotomus papatasi Scopoli 1786 (Diptera: Psychodidae) (Ben Ismail et al. 1987b, 1988). This vector frequently used rodents' burrows for daytime resting and breeding (Helal et al. 1987, Esseghir et al. 1993). Many ecological studies of the reservoir hosts identified three rodent species carrying L. major: Psammomys obesus Cretzschmar 1828 with a major part in amplifying the transmission, Meriones shawi Duvernoy 1842 and Meriones libycus Lichtenstein 1823 with a role to propagate the parasite between P. obesus colonies because of their common migration, thus increasing the distribution of the parasite (Bouratbine Balma 1988, Fichet-Calvet et al. 2000). P. obesus, the fat sand rat, is distributed through the semi-desert on the northern fringe of the Sahara, from Mauritania through Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Palestine, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. It is the main reservoir host of L. major and the source of epidemics in this region. Its local distribution is governed by that of the halophytic Chenopodiaceae on which it depends for food (Ashford 1996, 2000). These saline ecological biotopes are discontinuous in distribution in the Center and South of Tunisia, thus leading to a fragmentation of the populations of sand rats.

On the other hand, M. shawi is the reservoir host of L. major in some parts of Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco (WHO 1990, Wasserberg et al. 2002, Ben Salah et al. 2007). This desert rodent inhabits clay and sandy deserts, arid steppes, grasslands, and mountain valleys. It is seen essentially in fields in nonirrigated cereal crops, Ziziphus mounds and Opuntia hedges or in the bases of jujubes tufts (WHO 1992). It is a terrestrial rodent that spends most of time occupying underground burrows with several small chambers used for food storage (Nowak 1991).

According to Ashford and Jarry (1999), the P. obesus–P. papatasi–L. major association in North Africa and the Middle East constitute stable well-described zoonotic systems. On the other hand, the Meriones–sandfly–L. major systems that have been described from Morocco (Rioux et al. 1982) to India (Sharma et al. 1973) seem to be quite unstable, being associated with population surges of Meriones and outbreaks of cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans (Ashford 1986). In fact, few studies attempted to evaluate the prevalence of infection by L. major parasite in these species of rodents.

The aim of the present study was to compare the age structure, the morphological measurements, as well as the importance of Leishmania infection among natural reservoir hosts: P. obesus and M. shawi in Central Tunisia. This information is needed to evaluate the relative importance of different reservoirs in the maintenance of L. major transmission cycle as well as the role of M. shawi in the spatial expansion of the epidemic in naïve human populations outside the classic biotope of chenopods where P. obesus is predominant.

Materials and Methods

Study site and rodents collection

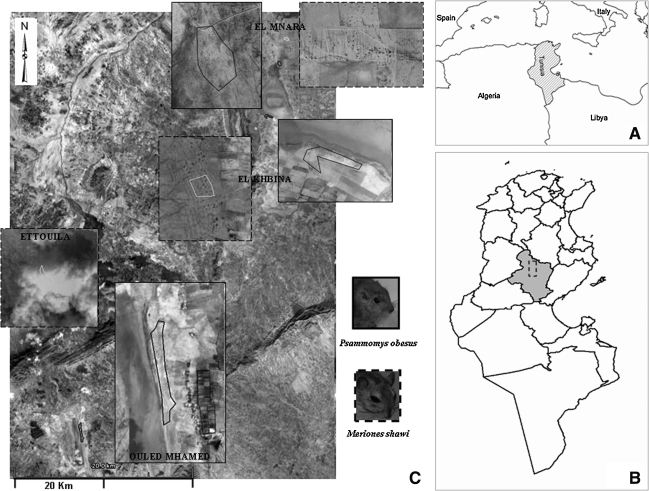

Rodents were trapped from six study sites (three sites for each species of rodents) in the endemic area for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sidi Bouzid, Central Tunisia. P. obesus was captured in EL KHBINA (average Altitude 198,7296 m; N35 11490 E9 43971); EL MNARA (average Altitude 205,1304 m; N35 14698,88 E9 44818,88); and OULED MHAMED (average Altitude 310,5912 m; N35 52527,25 E9 30036,5). These sites are located on a saltflat of halophytic vegetation. Predominantly, plants of the family Chenopodiaceae (Salsola, Suaeda, and Arthrocnemum spp., with occasional Atriplex sp.), represented the much disturbed remnants of the edge of the sebka (Ozenda 1991).

M. shawi was captured in EL KHBINA (average Altitude 221,8944 m; N35 10775,6 E9 43050,2); EL MNARA (average Altitude 215,7984 m; N35 16163,33 E9 45354,66); and ETTOUILA (average Altitude 434.035 2 m; N34 58436,83 E9 26281,5). The vegetation of these sites is composed of Arthrophytum sp., Retama sp., Ziziphus mounds, and Opuntia hedges (WHO 1992) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Study sites for the both species of rodents. (A) Location of Tunisian country in Mediterranean region. (B) Location of study area (delimited) at Sidi Bouzid Governorate (highlighted). (C) A land sat image of the study area with a zoom on bordered study sites of Psammomys obesus and Meriones shawi.

Two kinds of trap were used to catch rodents: unabated pincer traps placed in the mouths of the burrows and wire-mesh cage traps baited with fresh food-plants and placed close to active burrow entrances on the residual study site. Trappings were done over a period of 1 year with 4 days/nights for each site per month. Trapped rodents were collected from the field and transported to the laboratory for examination.

Age determination, body measurements, and clinical manifestations of Leishmania

The weight of the desiccated lenses of both eyes (eyes lenses weight [ELW]) was used as an indirect measure for age determination of rodents (Martinet 1966, Morris 1971, Gosling et al. 1980). Eyes were removed and preserved for at least 2 weeks in 10% formalin, and then the lens were extracted, dried for 2 h at 100°C, and weighed on a pan balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg (Fichet-Calvet et al. 2003). Besides age determination, these specimens were analyzed as regard to their body measurements. Clinical manifestations of Leishmania infection were assessed by a thorough skin examination. Signs included depilation, hyper-pigmentation of the higher edge of the ear, infiltration, and dissemination of parasites with the presence of small nodules or partial destruction of organs.

Detection of Leishmania by direct examination and culture

Each captured rodent was identified, sexed, and searched for cutaneous lesions in the different parts of the skin, mainly at the tail and in the ears. Both ears of each rodent caught were removed and macerated together in physiological saline. A subsample of the suspension produced from the ears of each rodent was removed in a slide, stained by May-Grunwald-Giemsa, and observed at 1000×for direct examination of Leishmania amastigotes. Another subsample was put on Coagulate Serum of Rabbit (CSR) for culture and the third one was inoculated subcutaneously into a hind foot-pad of a BALB/c mouse (Ben Ismail et al. 1989). The hind footpads of the inoculated mice were examined regularly until a lesion was observed or, if no lesion developed, until 5 months postinoculation. A mouse that developed a footpad lesion was declared positive for L. major if promastigotes are observed in cultures obtained from the swollen footpad in CSR medium.

Indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFAT)

The Indirect Fluorescent Antibody Test was standardized against L. major antigens. Standardization of the technique was made with progressive dilutions of positive and negative control sera (1:20 to 1:320) against progressive dilutions of the conjugate (1:50 to 1:1600) in Evans Blue. Stationary phase promastigotes were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 10 mL of a 107 parasites/mL suspension was dispensed in 12-well immunofluorescence slides. The latter were air-dried for 1 h at room temperature. Samples and control sera were incubated with parasites for 30 min at 37°C. After three washes in PBS, antibody fixation was revealed with fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (heavy plus light chains; Invitrogen) diluted at 1:100 in 0.01% Evans blue for counterstaining. The slides were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C, washed, and examined with a fluorescence microscope (Leica, DMIL LED). Only samples that showed fluorescent promastigotes, including the flagellum, were considered positive. The antibody titers were determined for positive sera at a titer 1:20 by testing them again in serial dilutions halving the concentration (Ben Ismail et al. 1989).

Data analysis

Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of the distribution of morphological variables. Continuous variables were compared using nonparametric tests for comparison of medians. χ2 as well as Fisher exact tests permitted to compare association of categorical variables. STATA software version 11 was used to carry out all statistical analysis (Stata Corporation).

Results

Between November 2008 and March 2010, a total of 639 rodents: 472 P. obesus and 167 M. shawi were captured in the study area. Among the captured rodents, we found 41 pregnant P. obesus females and, 9 pregnant M. shawi females with a number of embryos ranging between 2 and 9 per female. ELW ranged from less than 20 to 80 mg for P. obesus and reached 100 mg for M. shawi (Median=38.55 [95% confidence interval (CI)=9–74.6] vs. 61.6 [95% CI=20.6–113.1], respectively). ELW difference was significant between the two species (Nonparametric equality-of-medians test, p<0.001).

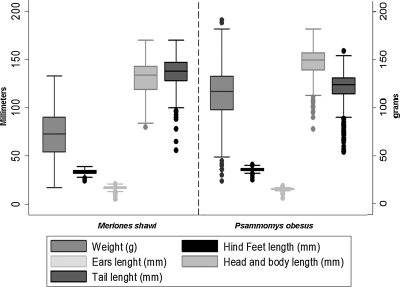

All the morphological variables distributions for P. obesus and M. shawi lacked normality. Therefore, comparisons were based on the median for these variables and showed significant differences between the two species (Table 1). P. obesus had a higher weight, a longer head-body, and hind foot compared to M. shawi. On the other hand, ears and tails were significantly longer among the latter (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Description of the Study Sample of Rodents: Study Sample Distribution by Location, Comparison of Demographic, and Morphometric Parameters

| Factors | P. obesus | M. shawi | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location of capture | |||

| Ettouila | No observation | 15 (9) | — |

| Khbina | 201 (43) | 137 (82) | <0.001 |

| Mnara | 131 (28) | 15 (9) | NS |

| Ouled Mhamed | 140 (30) | No observation | — |

| Total | 472 | 167 | — |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 176 (37) | 70 (42) | NS |

| Female | 296 (63) | 97 (58) | NS |

| Total | 472 | 167 | — |

| Median body measurements (IQ)a | |||

| Weight (g) | 117 (98–132.5) | 73 (54–90) | <0.001 |

| Ear length (mm) | 16 (15–16) | 17 (16–18) | <0.001 |

| Head and body length (mm) | 149.5 (139–157) | 134 (119–143) | <0.001 |

| Tail length (mm) | 124 (114.5–131) | 138 (128–147) | <0.001 |

| Hind Feet length (mm) | 36 (35–37) | 34 (32–35) | <0.001 |

| Age of rodents by classes of ELW (%) | |||

| <20 mg | 45 (10) | No observation | — |

| 20–30 mg | 109 (23) | 11 (7) | NS |

| 30–40 mg | 96 (20) | 18 (11) | NS |

| 40–50 mg | 88 (19) | 23 (14) | NS |

| 50–60 mg | 85 (18) | 28 (17) | NS |

| 60–70 mg | 41 (9) | 26 (16) | NS |

| 70–80 mg | 8 (2) | 20 (12) | NS |

| 80–90 mg | No observation | 23 (14) | — |

| 90–100 mg | No observation | 7 (4) | — |

| >100 mg | No observation | 11 (7) | — |

Median is the percentile of 50% and IQ are the percentiles of 25% and 75%.

P. obesus, Psammomys obesus; M. shawi, Meriones shawi; NS, not significant; IQ, InterQuartile Interval; ELW, eyes lenses weight.

FIG. 2.

Box plot presentation of morphological measurements among the two species of rodents. Y axis 1 in the left is in millimetres (mm), Y axis 2 in the right is in grams (g). X axis is divided in two parts: M. shawi measurements in the left and P. obesus in the right.

Infection prevalence

The importance of L. major infection varied among the two reservoirs according to the technique used. It was 7% versus 5% for culture (including the results of inoculated mice; p=not signifiant [NS]), 19% versus 16% for direct examination of smears (p=NS) and 20% versus 33% (p=NS) for IFAT among P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively.

The IFAT revealed a positive reaction at dilutions ranging from 20 to 640 for both rodents. Geometric mean (Gmean) of these titers was higher for M. shawi (Gmean=82.04, [95% CI=60.54 to 111.16]) than P. obesus (Gmean=59.07, [95% CI=49.76 to 70.12]) positive sera.

When we consider the combination of all diagnostic methods, the prevalence of infection was 34% for P. obesus and 41% for M. shawi (p=NS). Interestingly, this prevalence was significantly higher among female rodents compared to males of both populations (65% vs. 35% [p<0.001] and 66% vs. 34% [p=0.01] among P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively).

Clinical manifestations

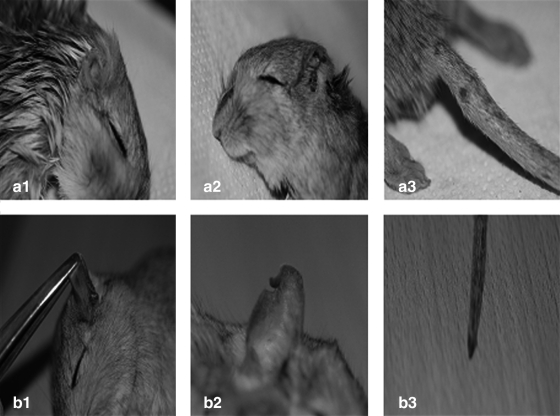

The clinical examination of rodents captured showed various aspects of skin lesions. When we consider any clinical sign among the whole study sample (n=639), disease was detected among 222 specimens of P. obesus (47%) and 73 specimens of M. shawi (43%; p=NS). Depilation, hyper-pigmentation, ignition, and severe edema of the higher edge of the ear were the most frequent signs observed in the study sample among both rodents (79% for P. obesus vs. 68% for M. shawi; p=NS) followed by the tail (Table 2). We also noticed infiltration and more obvious thickening of the part of the pinna, dissemination of parasites with the presence of small nodules, as well as partial destruction of this part. However, the lesions were bilateral and seemed to be more destructive in M. shawi than in P. obesus (Fig. 3). Table 2 details the relative importance of clinical signs observed among both reservoirs.

Table 2.

Clinical Manifestations of Leishmania Parasites in Both Species of Rodents

| Presence of clinical signs | P. obesus | M. shawi | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| All clinical signs included (%) | 222 (47) | 73 (43) | NS |

| Location of clinical signs (%) | |||

| Ear lesions | 175 (79) | 50 (68) | NS |

| Tail lesions | 77 (35) | 36 (49) | NS |

| Belly lesions | 11 (5) | 4 (5) | NS |

| Noose lesions | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | — |

| Back lesions | 1 (0) | No observation | — |

| Hind feet lesions | 3 (1) | 1 (1) | NS |

FIG. 3.

Examples of clinical manifestations observed among M. shawi (a) and P. obesus (b) in the study sample. (a1): Severe edema of the higher edge of the ear. (a2) Total destruction of the ear. (a3) Swelling on the proximal third of tail. (b1) Hyper-pigmentation on the ear. (b2) Depilation and thickening of the part of the Pinna. (b3) Hairless spots on the base of tail.

Patent infection defined as the proportion of rodents with any clinical sign among those who showed a positive test by any diagnostic method was 62% (99/159) versus 59% (40/68; p=NS) among P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively. Thus, asymptomatic infection among positives by any diagnostic methods was ∼40% for both rodents.

Evolution of the infection prevalence according to the season of capture and the age of rodents

The peak of the prevalence of leishmaniasis infection, among P. obesus population, was in November 2009 (57%), whereas the lowest was in April 2009 (17%). For M. shawi population the prevalence of infection was high in January 2009 (75%) and decreased subsequently. According to seasons, infection prevalence exceeded 22% and reached the maximum among both species of rodents in winter and autumn. Interestingly, during all seasons the prevalence of Leishmania infection seems to be higher, although not statistically significant, in M. shawi population compared to P. obesus population and exceeds 50% at the higher seasons of infection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Leishmania Infection Prevalence Between the Two Species of Rodents Among Seasons

| Seasons | Captured P. obesus (% of infection) | Captured M. shawi (% of infection) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late autumn and winter 1a | 157 (41) | 17 (53) | NS |

| Spring 2009 | 142 (22) | 22 (27) | NS |

| Summer 2009 | 79 (29) | 35 (31) | NS |

| Autumn 2009 | 58 (48) | 20 (50) | NS |

| Winter 2 and early springb | 36 (36) | 73 (42) | NS |

Winter 2009 and November 2008.

December 2009, February 2010, and March 2010.

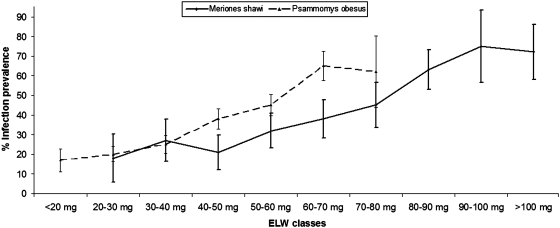

The trend of the prevalence of infection with age of rodents revealed a steady increase for both species from 20% for young generations to 66% and 75% for adult P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively, as shown in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Infection prevalence among different classes of eyes lenses weight (ELW: method used to estimate the rodent age) in each species of rodents (±standard error).

Discussion

The present study is to our knowledge the first one in North Africa assessing the importance of L. major infection and its clinical manifestation among P. obesus as well as M. shawi using a large sample size of both populations captured over 1-year period. Compared with Psammomys (n=472), the low numbers of Meriones (n=167) indicates that they are scattered in the study area, whereas the former are denser and restricted in chenopods fields.

Body measurements of the two species of rodents showed a wide range of body weight, head-body length, and tail length. All measurements of M. shawi were smaller than those reported by Darvish (2009). Unsurprisingly, body measurements of P. obesus were in agreement with those reported by Ben Hammou et al. (2006), who captured their study population in the same study area.

Age structure of the study sample of these rodents based on ELW would suggest that M. shawi had a longer longevity than P. obesus (three ELW classes surpass 80 mg for M. shawi). Indeed, the lowest ELW class (<20 mg) include a few rodents for P. obesus and zero capture for M. shawi. However, this parameter might be influenced by rodent's weights differences and/or the effect of method of capture used. Indeed, small rodents might escape from the unabated pincer traps technique.

Clinical expression of Leishmania infection ranged from small nodules to total destruction of external parts particularly the ears (average 67%) and tails (average of 27%). Surprisingly, infection seems to be more severe among M. shawi species. This finding, described for the second time in the literature (Ben Ismail et al. 1987a), is very striking because it would indicate either higher susceptibility or more virulence of L. major strains among this population of rodents. These hypotheses might be addressed in future studies.

Previous studies carried out on the rodents reservoirs of Leishmania parasite in the old world showed a broad range of the infection prevalence ranging from 3% to 100% for microscopy and from 1% to 40% for culture (Nadim and Faghih 1968, Edrissian et al. 1975, Elbihari et al. 1984, Githure 1986). This high variability might be partly explained by the cross-sectional study designs used in most studies that could not account for heterogeneity of transmission through time, as well as the small sample size that lead to high sampling fluctuations. Indeed, for M. shawi, the only study where the sample size exceeded 100 rodents, the prevalence of infection was of 2% by culture parasite method (Rioux et al. 1986). The prevalence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the present study was 19% versus 16% by microscopy and 7% versus 5% by parasite culture for P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively. These estimates are in the same range when compared to those reported in Tunisia and elsewhere for these species (Rioux et al. 1982, Schlein et al. 1984, Ben Ismail et al. 1987a, 1989, Fichet-Calvet et al. 2003).

Few studies used serological methods to evaluate the prevalence of leishmaniasis infection among rodents. To our knowledge, only five studies were carried out on different species of rodent reservoir hosts of leishmaniasis, including one study related to P. obesus and M. shawi (El Nahal et al. 1982, Morsy et al. 1982, 1990, Zovein et al. 1984, Ben Ismail et al. 1989). The values reported in our study for serological diagnosis by IFAT were 20% and 33% among P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively. These values are in agreement with those reported by Ben Ismail et al. (1989) for the same method but they were very low compared with the serological study of Rhombomys opimus where a very high rate of infection was found (Zovein et al. 1984). Different estimations of infection prevalence according to the diagnostic method might also reflect variations in sensitivity and specificity of each method.

The overall prevalence of 34% for P. obesus and 41% for M. shawi showed in this study was high compared to those observed in other studies of both reservoir hosts in Tunisia (Ben Ismail et al. 1987a, 1989, Fichet-Calvet et al. 2003). Approximately 60% in both species of rodents had detectable lesions by clinical examination. Discordance between clinical manifestations and presence of leishmaniasis infection (average of 50% for both species of rodents) might be explained either by nonspecific clinical signs for leishmaniasis or lack of sensitivity of diagnostic tools used in the present study. This study shows the importance of asymptomatic infection (∼40%) in both rodents' species. This finding, proven for the first time in M. shawi, was already reported for P. obesus (Fichet-Calvet et al. 2003). It might be explained either by young age of captured rodents showing asymptomatic infection or a variability in the Leishmania parasites infecting rodents. In agreement with previous studies, female rodents revealed higher infection prevalence for both species (∼65%) (Rechav 1970, Ben Ismail et al. 1987a).

The combined results of diagnostic methods showed a high variation in the prevalence of leishmaniasis infection among both rodents through time with a lowest level in April and a highest level in November for P. obesus, which corroborates the findings of Fichet-Calvet et al. (2003). According to our study, the infection was absent in September and November and reached 70% in January for M. shawi. This result could imply an alternation of the parasite between these two rodent reservoir hosts to continuously maintain the transmission of the parasite within a sylvatic cycle.

In the present study, Leishmania infection increased proportionally with age and became high among adult rodents of both species (60% and 70% for P. obesus and M. shawi, respectively), suggesting a low death rate among infected rodents. This result is reported for the first time for M. shawi species.

The present study confirmed that M. shawi plays an important role in the transmission of L. major in Tunisia. The relatively high prevalence shows that this reservoir, because of its movements, its longevity as well as its close relationship to human settlements, could contribute significantly in the dispersal of Leishmania parasites leading to the emergence of epidemics in new foci among naïve populations.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks extended to Ms. Rihab Yazidi and Ms. Sana Chaâbane (Pasteur Institute of Tunis) for here technical contribution in Leishmania strains culture. We also thank Kamel Belgacem (Pasteur Institute of Tunis) for contribution in rodent's capture. We are grateful to Mr. Hichem Dridi (Pasteur Institute of Tunis), who facilitated access to the field.

The present study is part of a research project supported by US-NIAID-NIH, Grant number 1P50AI074178-01, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pasteur Institute of Tunis. All animal experimentations were in agreement with the guidelines of International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Ashford RW. Leishmania: Taxonomie et Phylogenèse. In: Rioux JA, editor. Applications éco-épidemiologiques. Montpellier: IMEEE, Coll. Int. CNRS/INSERM; 1986. pp. 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RW. Leishmaniasis reservoirs and their significance in control. Clin Dermatol. 1996;24:523–532. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RW. The leishmaniases as emerging and reemerging zoonoses. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RW. Jarry DM. Épidémiologie des leishmanioses de l'Ancien Monde. In: Dedet JP, editor. Les leishmanioses; Ellipses, Paris: 1999. pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Hamou M. Ben Abderrazak S. Frigui S. Chatti N, et al. Evidence for the existence of two distinct species: Psammomys obesus and Psammomys vexillaris within the sand rats (Rodentia, Gerbillinae), reservoirs of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R. Ben Rachid MS. Gradoni L. Gramiccia M, et al. Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Tunisia: study of the disease reservoir in the Douara area. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1987a;67:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R. Gramiccia M. Gardoni L. Helal H, et al. Isolation of Leishmania major from Phlebotomus papatasi in Tunisia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987b;81:749. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(87)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R. Hellal H. Sidhom M. Ben Rachid MS. Le cycle de la transmission de la leishmaniose cutanée zoonotique en Tunisie. Tunis Med. 1988;66:353. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ismail R. Khaled S. Makni S. Ben Rachid MS. Anti-leishmanial antibodies during natural infection of Psammomys obesus and Meriones shawi (Rodentia, Gerbillinae) by Leishmania major. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1989;69:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Salah A. Kamarianakis Y. Chlif S. Ben Alaya N, et al. Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Central Tunisia: spatio–temporal dynamics. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:991–1000. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouratbine Balma A. Thèse Médecine. Faculté de Medecine de Tunis; Tunis: 1988. Etude Eco-épidémiologique de la leishmaniose cutanée zoonotique en Tunisie (1982–1987) p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Darvish J. Morphmetric comparison of fourteen species of the genus Meriones Illiger, 1811 (Gerbillinae, Rodentia) from Asia and North Africa. Iranian J Animal Biosystematics. 2009;5:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Edrissian GH. Ghorbani M. Tahvildar Bidruni G. Meriones persicus, another probable reservoir of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1975;69:517–519. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(75)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbihari S. Kawasmeh ZA. Al Naiem AH. Possible reservoir host(s) of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Al-Hassa oasis, Saudi Arabia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1984;78:543–545. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1984.11811861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Nahal HS. Morsy TA. Bassili WR. El Missiry AG, et al. Antibodies against three parasites of medical importance in Rattus sp. collected in Giza Governorate Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1982;12:287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esseghir S. Ftaiti A. Ready PD. Khadraoui B, et al. The squash blot technique and the detection of L. major in Phlebotomus papatasi in Tunisia. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 1993;70:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E. Jomaa I. Ben Ismail R. Ashford RW. Leishmania major infection in the fat sand rat Psammomys obesus in Tunisia: interaction of host and parasite populations. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97:593–603. doi: 10.1179/000349803225001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E. Jomaa I. Zaafouri B. Ashford RW, et al. The spatio-temporal distribution of a rodent reservoir host of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Appl Ecol. 2000;37:603–615. [Google Scholar]

- Githure JI. Characterization of Kenyan Leishmania spp. and identification of Mastomys natalensis, Taterillus emini and Aethomys kaiseri as new hosts of Leishmania major. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1986;80:501–507. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1986.11812056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling LM. Huson LW. Addison GC. Age estimation of Coypus (Myocastor Coypus) from eye lens weight. J Appl Ecol. 1980;17:641–647. [Google Scholar]

- Helal H. Ben Ismail R. Bach-Hamba D. Sidhom M, et al. Enquête entomologique dans le foyer de leishmaniose cutanée zoonotique (Leishmania major) de Sidi Bouzid, Tunisie en 1985. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1987;80:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinet L. Détermination de l'age chez le campagnol des champs (Microtis arvalis) par la pesée du cristallin. Mammalia. 1966;30:425–430. [Google Scholar]

- Morris P. A review of mammalian age determination methods. Mamm Rev. 1971;2:69–104. [Google Scholar]

- Morsy TA. Hamadto HA. Rashed SM. El-Fakahany AF, et al. Animals as reservoir hosts for Leishmania in Qualyobia Governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1990;20:779–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy TA. Michael SA. Bassili WR. Saleh MSM. Studies on rodents and their zoonotic parasites. Particularly Leishmania, in Ismailya Governorate, A.R. Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1982;12:565–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A. Faghih M. The epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Isfahan province of Iran, I. The reservoir II. The human disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1968;61:534–550. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(68)90140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak RM. Walker's guide to the mammals of the world. 5th. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ozenda P. Flore et Végétation du Sahara. 2nd. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche scientifique; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rechav Y. Effect of age and sex of gerbils on the attraction of immature Hyalomma excavatum koch, 1844 (ixodoidea: ixodidae) J Parasitol. 1970;56:611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux JA. Petter F. Akalay O. Lanotte G, et al. Meriones shawi (Duvernoy, 1842) [Rodentia, Gerbillidae] a reservoir of Leishmania major, Yakimoff and Schokhor, 1914 [Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae] in South Morocco. C R Seances Acad Sci III. 1982;294:515–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux JA. Petter F. Zahaf A. Lanotte G, et al. Isolement de Leishmania major Yakimoff et Schokhor, 1914 (Kinetoplastida-Trypanomatidae) chez Meriones shawi shawi (Duvernoy, 1842) (Rodentia, Gerbillidea) en Tunisie. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1986;61:139–145. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1986612139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y. Warburg A. Schnur LF. Le Blancq SM, et al. Leishmaniasis in Israel: reservoir hosts, sandfly vectors and leishmanial strains in the Negev, Central Arava and along the Dead Sea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:480–484. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MID. Suri JC. Kalra NL. Mohan K. Studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in India. III. Detection of a zoonotic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Rajasthan. J Commun Dis. 1973;5:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserberg G. Abramskya Z. Andersb G. El-Faric M, et al. The ecology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Nizzana, Israel: infection patterns in the reservoir host, and epidemiological implications. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:133–143. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Control of leishmaniasis. Report of WHO Expert Committee, technical report series. Vol. 793. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1990. p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Report of the WHO meeting on rodent ecology, population dynamics and surveillance technology in Mediterranean countries. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zovein A. Edrissian GH. Nadim A. Application of the indirect fluorescent antibody test in serodiagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in experimentally infected mice and naturally infected Rhombomys opimus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78:73–77. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]