Abstract

Background

Many persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) treated with galantamine appear to receive additional cognitive benefit from citalopram. Both drugs inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE). These enzymes co-regulate acetylcholine catabolism. In AD brain, AChE is diminished while BuChE is not, suggesting BuChE inhibition may be important in raising acetylcholine levels. BuChE is subject to activation at high acetylcholine levels reached at the synaptic cleft. The present study explores one way combining galantamine and citalopram could be beneficial in AD.

Methods

Spectrophotometric studies of BuChE catalysis in the absence or presence of galantamine or citalopram or both, were performed using the Ellman method. Data analysis involved expansion of our previous equation describing BuChE catalysis.

Results

Galantamine completely inhibited BuChE at low substrate concentrations (VS = 42.0 μM/min; VS(gal) = 0) without influencing the substrate-activated form of the enzyme (VSS = VSS(gal) = 62.3 μM/min). Conversely, citalopram inhibited both un-activated (VS = 42.0 μM/min; VS(cit) = 6.75 μM/min) and substrate-activated (VSS = 62.3 μM/min; VSS(cit) = 45.2 μM/min) forms of BuChE. Combined galantamine and citalopram increased inhibition of un-activated BuChE (VS = 42.0 μM/min; VS(gal)(cit) = 0.85 μM/min) and substrate-activated form (VSS = 62.3 μM/min; VSS(gal)(cit) = 45.0 μM/min).

Conclusion

Citalopram and galantamine produce a combined inhibition of BuChE considered to be synergistic.

General Significance

Clinical benefit from combined galantamine and citalopram may be related to a synergistic inhibition of BuChE, facilitating cholinergic neurotransmission. This emphasizes the importance of further study into use of drug combinations in AD treatment.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cholinesterase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, enzyme kinetics, dementia

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by dysfunction of cholinergic activity in the central nervous system resulting from the loss of cholinergic neurons and a reduction in brain levels of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine [1–4]. This reduction in acetylcholine is accompanied by a decrease in the activity of its principal hydrolytic enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE, E.C. 3.1.1.7). In contrast, in AD, the other acetylcholine hydrolase, butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE, E.C. 3.1.1.8), has been reported to remain at normal levels [5,6] or even be elevated in the brain [7]. Therefore, BuChE may be a significant contributor to the observed loss of acetylcholine in AD [8].

Current treatment of AD involves the use of drugs, such as donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine, that are cholinesterase inhibitors [9]. Although cholinesterase inhibitors have been used for this indication for many years, new attention is being paid to how they work, in part because of consecutive failure of all non-cholinesterase-inhibitor treatments [10]. This new focus on cholinesterase inhibitor efficacy has encompassed many paths, such as directed design of cholinesterase inhibiting compounds that have therapeutically active functions beyond cholinesterase inhibition [11–12], improved understanding of regional specificity effects [13], genetic determinant linkages to variable drug responses [14], or exploring mechanisms by which current or next generation of cholinesterase inhibitors might be disease-modifying [15]. These each represent areas in which better cholinesterase inhibitors, or better use of them, might enhance therapeutic potential. Further, currently used cholinesterase inhibitors raise brain acetylcholine levels, probably because they inhibit not just AChE, but also BuChE, an area that requires additional inquiry [16, 17]. For example, selective inhibition of BuChE increases brain acetylcholine levels and improve cognitive function [18–22].

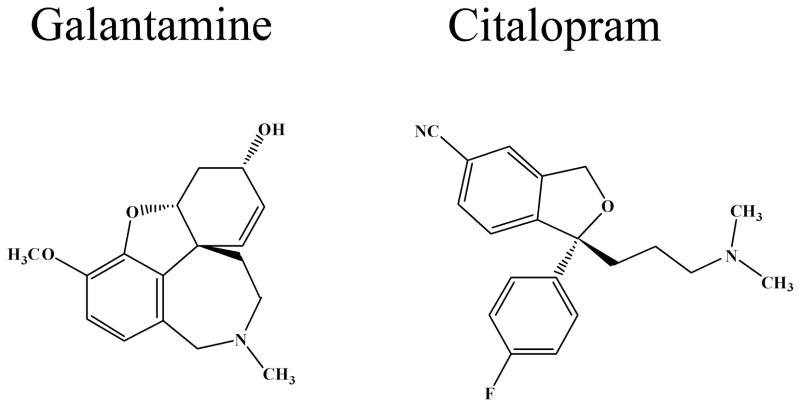

Clinically, the need for better treatment of persons with AD has prompted many responses, including the empirical use of drug combinations. For example, in addition to cholinergic dysfuntion, the serotonergic system becomes progressively affected in AD [23], which may contribute to some of the symptoms of the disease [24]. Therefore, there has been interest in examining whether serotonergic drugs can be used in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors for treatment. Citalopram (Fig. 1) is an anti-depressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class [25]. Preliminary evidence from imaging studies [26] suggests that AD patients treated with galantamine (Fig. 1) may have additional improvement in cerebral blood flow when also treated with citalopram. Corroborating clinical evidence of this observation is lacking, although a small study suggests potential for some clinical effect [27].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of galantamine and citalopram.

This apparent drug synergy may also be due, at least in part, to the ability of citalopram to act as a cholinesterase inhibitor [28], thereby enhancing acetylcholine levels by augmenting the cholinesterase inhibitory action of galantamine. In the present study our objective was to examine the combined effects of galantamine and citalopram on the kinetic behavior of BuChE, as one approach to understanding the complex potential benefits of certain multi-drug prescription in patients receiving care for AD [27]. In the present study, we have developed a method, based on our previous analysis of BuChE inhibition [29], to kinetically describe the combined effect of galantamine and citalopram on this enzyme. Our findings indicate that the interplay between serotonergic drugs and cholinesterase inhibitors may be complex and need to be further examined to rationalize their beneficial effects on the symptomatic treatment of AD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Butyrylthiocholine, citalopram hydrobromide and 5, 5′-dithio-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Galantamine was provided by Janssen-Ortho Inc., at our request, through a Material Transfer Agreement. Butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE, EC 3.1.1.8), purified from human plasma (10 units = 0.16 nmole), was a gift from Dr. Oksana Lockridge (University of Nebraska Medical Center).

2.2. Butyrylcholinesterase activity

Purified serum BuChE was used in this study since its kinetic parameters were earlier found to be comparable to those obtained with BuChE isolated from human brain tissue [6].

The esterase activity of BuChE was determined by a modification [17] of the Ellman method [30], using butyrylthiocholine as substrate. Briefly, a working DTNB solution was prepared by mixing 3.6 mL of a stock solution, containing 10 mM DTNB and 20 mM NaHCO3 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.0, with 96.4 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. The assays were carried out by mixing 1.35 mL of buffered DTNB working solution (pH 8.0), 0.05 mL (0.04 unit) of BuChE solution in 0.1% aqueous gelatin and 0.05 mL of distilled water or 0.05 mL of galantamine or citalopram or both, dissolved in 50% aqueous acetonitrile, in a cuvette of 1 cm path-length. Absorbance of this solution was calibrated to zero and the reaction was commenced by adding 0.05 mL of aqueous butyrylthiocholine to produce reaction mixtures with substrate concentrations varying between 2.0 × 10−5 and 8.0 × 10−3 M. The final reaction volume was 1.5 mL. The reactions were performed at 23°C. The rate of change of absorbance (ΔA/min), reflecting the rate of hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine, was recorded every 5 seconds for 1 minute, using a Milton-Roy uv-visible spectrophotometer, set at λ = 412 nm to provide data for determining the initial rate of hydrolysis.

0.04 unit BuChE is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces a Δ;A/min of 0.400 absorbance units under standard conditions using 1.6 × 10−4 M as final concentration of substrate.

2.3. Determination of kinetic constants

The initial rate of substrate hydrolysis was obtained for all raw data by plotting change in absorbance, due to substrate hydrolysis, against time and fitting the data to a second degree polynomial equation, using the Microsoft Excel program. The derivative of this equation allowed determination of the expression for the change in rate over time. Extrapolation of the linear relationship to zero gave the initial rate to be used for determining kinetic constants for the enzyme.

2.4. Global data fitting to test equations

Global data fitting to equations is the best method for testing the ability of a particular equation to describe observed data [31]. Observed maximum velocities (VS, VSS) and substrate binding constants (KS, KSS), in the presence and absence of enzyme inhibitor or activator, were determined using the solver feature of Microsoft Excel [32]. This solver feature was used to vary the values of enzyme constants to determine the minimum difference between the observed and calculated values, that is, the minimum sum of absolute residual values. Observed changes in the enzyme kinetic constants for each enzyme induced by the inhibitor or activator were used to estimate preliminary kinetic constants to begin equation fitting. Equation fitting, using the solver feature of Microsoft Excel, was then carried out to minimize the sum of absolute residual values and maximize global data fitting.

3. Results and Discussion

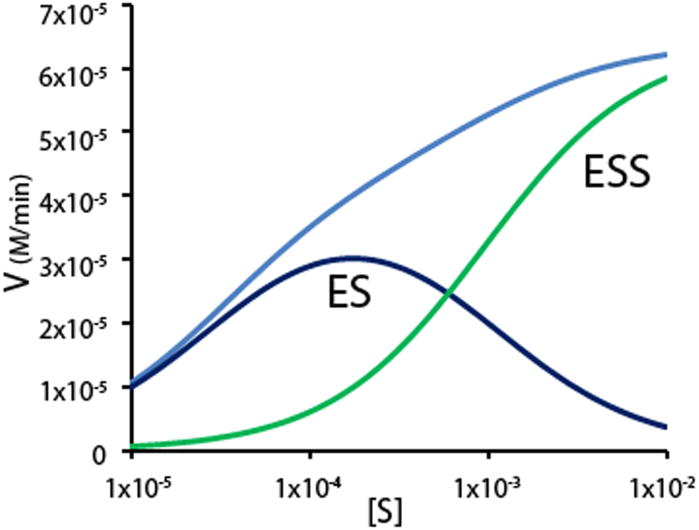

Unlike AChE, which is known to be inhibited by acetylcholine at high concentrations (>1 mM), BuChE enzyme activity is stimulated under the same conditions [29, 33]. That is, at substrate concentrations below 1 mM, BuChE activity conforms to Michaelis-Menten kinetics and catalytic activity proceeds through a simple enzyme-substrate complex (ES) (Fig. 2). However, at elevated substrate concentration (>1 mM) the enzyme exhibits greater activity due to the predominance of a substrate-activated complex (SES) (Fig. 2) that overrides the usual Michaelis-Menten substrate saturation-of-enzyme phenomenon, leading to the observed kinetic behavior of BuChE (Fig. 2). In vivo the average concentration of acetylcholine within the synaptic cleft has been estimated to reach as high as 5 mM [34–36]. This suggests that the substrate activated form of BuChE is present in the synaptic cleft and that inhibition of this form of the enzyme is also important in raising acetylcholine levels in AD brain to improve cognition.

Fig. 2.

Contributions of the substrate activated and un-activated forms to total observed butyrylcholinesterase activity over a wide range of substrate concentrations. The observed activity is represented by the light blue line while the substrate-activated form (SES) is green and the un-activated form (ES) is in dark blue.

3.1. Drug Effects on Butyrylcholinesterase Kinetics

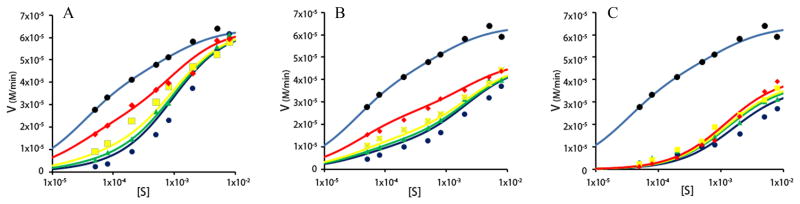

The presence of galantamine was observed to produce a concentration-dependent inhibition of BuChE activity at low substrate concentration (e.g., 1 × 10−4 M in Fig. 3A) but was found not to affect BuChE activity at elevated substrate concentration (i.e., lines converging with the no inhibitor line at 10 mM substrate concentration in Fig. 3A). In contrast, citalopram inhibited BuChE activity over the entire range of substrate concentrations from 5 × 10−5 M to 8 × 10−3 M (Fig. 3B). These observations (Fig. 3A and B) indicate that galantamine blocks product formation through the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) but is unable to exert an inhibitory effect (Fig. 3A) on the substrate-activated complex (SES). On the other hand, citalopram interacts with both the un-activated complex (ES) and the activated complex (SES) to inhibit BuChE activity over a wide range of substrate concentrations (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Kinetic plots of the enzymatic activity of butyrylcholinesterase in the absence and presence of galantamine and/or citalopram. For all experiments concentrations of 50, 80, 200, 500, 800 μM and 2, 5, 8mM butyrylthiolcholine substrate were used. All plots are expanded to a logarithmic scale to emphasize the difference in inhibitor activity between substrate un-activated and activated forms of butyrylcholinesterase. A) Rate of hydrolysis of substrate by butyrylcholinesterase without galantamine (light blue), or with 2 μM (red), 10 μM (yellow), 20 μM (green) and 50 μM (dark blue) galantamine. B) Rates of hydrolysis of substrate by butyrylcholinesterase without citalopram (light blue), or with 10 μM (red), 50 μM (yellow), 100 μM (green) and 250 μM (dark blue) citalopram. C) Rate of hydrolysis of substrate by butyrylcholinesterase without inhibitor (light blue), or with 50 μM galantamine and 10 μM citalopram (red), 20 μM galantamine and 50 μM citalopram (yellow), 10 μM galantamine and 100 μM citalopram (green), 2 μM galantamine and 250 μM citalopram (dark blue). Note that the greatest butyrylcholinesterase inhibition occurred with mixing the lowest concentration of galantamine and the highest concentration of citalopram (dark blue line).

Fig. 3C shows the combined inhibitory effects of mixtures of galantamine and citalopram in a variety of proportions. Note that the greatest inhibition of BuChE activity over the entire range of substrate concentration occurred with the mixture containing the lowest concentration of galantamine (2.02 × 10−6 M) and the highest concentration of citalopram (2.48 × 10−4 M) used. This latter observation implies a synergistic inhibition of BuChE by galantamine and citalopram that is greater than the sum of the individual effects. Furthermore, it suggests that, although galantamine is unable to bind to the substrate-activated form of the enzyme on its own (Fig. 3A), it can do so in the presence of citalopram (Fig. 3C).

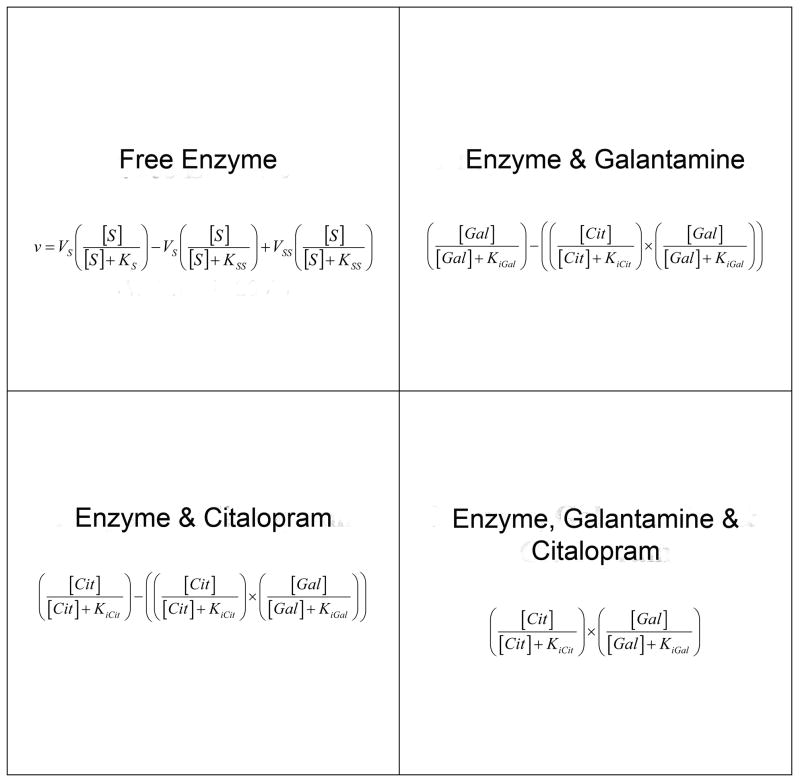

3.2. Development of a Kinetic Model

To describe the apparent synergy of the mixed BuChE inhibitors, galantamine and citalopram, a kinetic model was developed, based on mass action assumptions and on a previously developed model for BuChE kinetic behaviour [29] (Figure 4 top left) Terms representing the binding effect of each inhibitor in the presence of the other are depicted in the other three quadrants of the schematic outlined in Fig. 4 where the total enzyme population is composed of free enzyme or a combination of enzyme with each inhibitor or both inhibitors.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the equation for hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine by butyrylcholinesterase (top left ref 28) and terms reflecting the inhibitory interactions between butyrylcholinesterase and galantamine (top right), citalopram (bottom left) or both (bottom right). The entire area represents of the whole enzyme population. Each inhibitor is represented at a concentration equal to its Ki so that if only one inhibitor were present it would only be occupying half of the enzyme population. Incorporated into each quadrant, where inhibitor is present, is the mass action binding term representing the fraction of the enzyme population in association with an inhibitor. In the kinetic model described here, butyrylcholinesterase is subject to substrate activation so the mass action binding constants for the substrate activated and substrate un-activated forms would be different. Each quadrant with inhibition results in a novel effect on the un-inhibited catalytic constants (equation, top left quadrant) which contributes to the overall observed experimental activity (Table 1).

This model assumes that the binding of each inhibitor is independent of the other and that each has its own unique effect on the enzyme. In this approach, each inhibitor is represented at a concentration equal to its known independent affinity constant (Ki value) so that if only one inhibitor were present it would only be bound to half the total enzyme population. Since there will be two inhibitors present, the effect of each inhibitor on the enzyme population will depend on each inhibitor binding to a portion of the enzyme population, less the product of having both compounds interacting with the enzyme. The fourth quadrant (Fig. 4, bottom right) in the schematic represents the fraction of the enzyme population having both inhibitors bound simultaneously. Each inhibitor-affected quadrant of the enzyme population (Fig. 4, top right and bottom) results in a unique catalytic effect on the uninhibited catalytic constants, Ks, Kss, Vs and Vss, in Table 1 and contributes to the overall observed experimental BuChE activity. As indicated in Table 1, binding of galantamine to BuChE (Ki(gal)) produces a new substrate affinity constant (Ks(gal)) that indicates a 300-fold decrease in enzyme-substrate affinity and a new maximum velocity (Vs(gal)) for the un-activated form of the enzyme. Similarly, the binding of citalopram to the un-activated enzyme diminished the kinetic parameters from Ks and Vs to Ks(cit) and Vs(cit) (Table 1). Since this model treats the binding of each inhibitor as an exclusive event, the same binding constants, determined by their individual interaction with BuChE, were used to predict the portion of the enzyme population that would be associated with both inhibitors at any time. This model produced a 5-fold decrease in substrate affinity (KS(gal)(cit)) and a 49-fold decrease in maximal velocity (VS(gal)(cit)) values associated with the un-activated form of BuChE (ES) (Fig. 3C; Table 1), that show further decrease in substrate affinity and rate of hydrolysis.

Table 1.

Inhibition constants, substrate affinity constants and maximum reaction velocities for un-activated and substrate-activated forms of butyrylcholinesterase in the absence and presence of galantamine, citalopram or both. As this model does not take into account the effect one inhibitor may have on the binding of another all inhibition constants are based on the independent association of the enzyme and inhibitor complex. Kinetic constants were generated by using global equation fitting to the raw data with the solver function of Excel [33].

| Enzyme Form | Inhibition Constants | |

|---|---|---|

| Un-activated | Ki(gal) | Ki(cit) |

| 242 μM | 17.5 μM | |

| Substrate-activated | Ki(gal)2 | Ki(cit)2 |

| 1.80 μM | 0.52 μM | |

| Substrate Affinity Constants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Un-activated | KS | KS(gal) | KS(cit) | KS(gal)(cit) |

| 29.2 μM | 9.58 mM | 82.5 μM | 14.7 mM | |

| Substrate-activated | KSS | KSS(gal) | KSS(cit) | KSS(gal)(cit) |

| 0.76 mM | 9.58 mM | 1.59 mM | 10.4 mM | |

| Maximum Reaction Velocity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Un-activated | VS | VS(gal) | VS(cit) | VS(gal)(cit) |

| 42.0 μM/min | 0 | 6.75 μM/min | 0.85 μM/min | |

| Substrate-activated | VSS | VSS(gal) | VSS(cit) | VSS(gal)(cit) |

| 62.3 μM/min | 62.3 μM/min | 45.2 μM/min | 45.0 μM/min | |

Changes in kinetic parameters (KSS and VSS) are also observed with the substrate-activated form of the enzyme (SES), giving KSS(cit) and VSS(cit) (Table 1). However, while galantamine did not appear to affect the catalytic activity of substrate-activated BuChE on its own (Fig. 3A), it did produce a synergistic inhibition of the enzyme in the presence of citalopram (KSS(gal)(cit) and VSS(gal)(cit); Table 1 and Fig. 3C). The results indicate a 14-fold decrease in substrate affinity and a 1.4-fold decrease in maximum velocity of substrate hydrolysis. The binding constants determined from the effects observed with both inhibitors are therefore listed as the binding constants for galantamine and citalopram on the substrate-activated form of BuChE (Table 1).

3.3. Developing an equation to describe inhibition by citalopram and galantamine

The general form of the kinetic equation (Fig. 4, top left quadrant), used to describe BuChE catalysis over a wide range of substrate concentrations, has been reported previously [29]. The general term used to describe the inhibitory effects on each of the kinetic constants (C) in this equation (Fig. 4, top left) is refined using the following:

In this expansion, C represents unaltered kinetic constants for BuChE, such as the substrate affinities (KS, KSS) and maximum velocities (VS, VSS). The Δ terms are representative of the changes in the enzyme kinetic constants that are induced by the presence of the inhibitors separately and together. For example, the first Δ term (Δ1), represents the change induced by the binding of citalopram where the change in the kinetic constants, such as the substrate affinity constant, can be defined as Δ1 = (KS−KS(gal)). These values are summarized in Table 1.

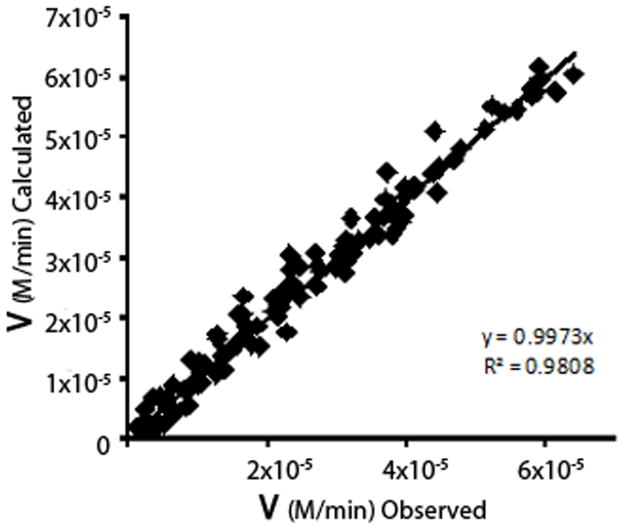

Applying the complete model to the observed kinetic values (Table 1) produced a good fit (calculated vs. observed) for the interactions of each inhibitor with BuChE and for their combined effect on the enzyme (Fig. 5). This model was also able to quantify the effect of citalopram on the activated form of BuChE induced by the presence of galantamine. That is, the affinity of activated BuChE for the substrate butyrylthiocholine (KSS(cit) = 1.59 mM) decreases by some 6-fold in the presence of both inhibitors (KSS(gal)(cit) = 10.4 mM). Note that this large decrease in BuChE affinity occurs even though galantamine alone does not affect the substrate-activated form of the enzyme (Table 1; Fig. 3A). That this form of polynomial inhibitory modeling scheme represents a reasonable approach to describing the combined effects of galantamine and citalopram is indicated by the linear relationship obtained when the observed and calculated rate values for the inhibition of BuChE are compared in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Plot showing linearity of experimentally observed and calculated rate values.

These observations provide one approach to our understanding of how the action of cholinesterase inhibitors may be enhanced in the presence of other commonly used medications in everyday practice. However, pivotal clinical trials typically select healthier groups of patients than those in whom such drug combinations are usually used. Older adults being treated with a cholinesterase inhibitor for AD often have co-morbidities, such as depression, cardiovascular disease and hypercholesterolemia, that require other drugs for proper management. In such instances it is important to ascertain, if possible, whether a second drug is affecting the action of the primary drug. For example, the general antidepressant, amitriptyline, is known to have a large number of sites of action. One of these activities is as an acetylcholine receptor antagonist that would be counter-productive toward the action of cholinesterase inhibitors that are intended to raise acetylcholine levels and improve cholinergic neurotransmission. On the other hand, certain statins used to treat hypercholesterolemia are BuChE inhibitors [37] and could provide additional benefit to patients being treated for AD. As experience with cholinesterase inhibitors broadens, there is increased interest in co-morbidities that might affect disease expression and which are commonly excluded from the original pivotal trials. Depression is an important example since depressive symptoms are common in AD. This likely reflects that, in some patients, the co-existence of cognitive impairment and depression indicates impairment of multiple transmitter systems, even at the outset. The common experience with AD patients who are treated with cholinesterase inhibitors having some depression-related symptoms, such as decreased initiation, suggests that some of these symptoms reflect cholinergic hypofunction. Even so, to fully test whether galantamine and citalopram have observable combined effects in clinical practice, which are attributable to a synergistic effect, will require clinical trials with pharmacokinetic studies.

4. Conclusions

If citalopram enhances the effect of galantamine with respect to important symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, there are two important possibilities about how this might happen. Clearly, activity on the serotonergic system would be important here, in addition, we draw attention that citalopram increases cholinesterase inhibition. We have shown that citalopram does so by inhibiting, like galantamine, the un-activated enzyme-substrate complex (ES) and, in addition, inhibits the substrate-activated complex (SES) that is not affected by galantamine. Furthermore, a combination of these drugs produces an inhibitory effect on BuChE that is greater than either agent alone. Such synergistic inhibition of BuChE, which should result in increased brain acetylcholine levels, would provide an additional rationale for any clinical benefit for AD patients treated with both galantamine and citalopram. This is particularly of interest because BuChE, in contrast to AChE which is reduced in AD, remains at normal [5,6] or elevated levels [7]. For this reason, it has been suggested that BuChE may in fact be the enzyme that is a major factor in depletion of acetylcholine levels in AD.

This study adds to the growing appreciation of new ways to investigate how the effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors might be extended, and particularly calls attention to the need to evaluate possible synergistic effects between medications, used for other reasons, and cholinesterase inhibitors in AD patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institutes of Health (US), Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada, Capital District Health Authority Research Fund, Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, the Committee on Research and Publications of Mount Saint Vincent University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1976;2:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Clark AW, Coyle JT, DeLong MR. Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann Neurol. 1981;10:122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atack JR, Perry EK, Bonham JR, Candy JM, Perry RH. Molecular forms of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in the aged human central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1986;47:263–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darvesh S, Reid GA, Martin E. Biochemical and histochemical comparison of cholinesterases in normal and Alzheimer brain tissues. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;5:386–400. doi: 10.2174/156720510791383868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Changes in brain cholinesterases in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1978;4:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1978.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesulam M, Guillozet A, Shaw P, Quinn B. Widespread butyrylcholinesterase can hydrolyze acetylcholine in the normal and Alzheimer brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:88–93. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birks J. Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2006;1:cd.005593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker RE, Greig NH. Why so few drugs for Alzheimer’s disease? Are methods failing drugs? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:642–651. doi: 10.2174/156720510793499075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tumiatti V, Minarini A, Bolognesi ML, Milelli A, Rosini M, Melchiorre C. Tacrine derivatives and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1825–1838. doi: 10.2174/092986710791111206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toda N, Kaneko T, Kogen H. Development of an efficient therapeutic agent for Alzheimer’s disease: design and synthesis of dual inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase and serotonin transporter. Chem Pharm Bull. 2010;58:273–287. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley P, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Modulation of fusiform cortex activity by cholinesterase inhibition predicts effects on subsequent memory. Brain. 2009;132:2356–2371. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam B, Hollingdrake E, Kennedy JL, Black SE, Masellis M. Cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body spectrum disorders: the emerging pharmacogenetic story. Hum Genomics. 2009;4:91–106. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toiber D, Berson A, Greenberg D, Melamed-Book N, Diamant S, Soreq H. N-acetylcholinesterase-induced apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2008;1:e3108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darvesh S, Hopkins DA, Geula C. Neurobiology of Butyrylcholinesterase. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:131–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darvesh S, Walsh R, Kumar R, Caines A, Roberts S, Magee D, Rockwood K, Martin E. Inhibition of human cholinesterases by drugs used to treat Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003;17:117–126. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Q, Holloway HW, Utsuki T, Brossi A, Greig NH. Synthesis of novel phenserine-based-selective inhibitors of butyrylcholinesterase for Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1855–1861. doi: 10.1021/jm980459s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacobini E, Spiegel R, Enz A, Veroff AE, Cutler NR. Inhibition of acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by rivastigmine: correlation with cognitive benefit. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:1053–1065. doi: 10.1007/s007020200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greig NH, Utsuki T, Ingram DK, Wang Y, Pepeu G, Scali C, Yu QS, Mamczarz J, Holloway HW, Giordano T, Chen D, Furukawa K, Sambamurti K, Brossi A, Lahiri DK. Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17213–17218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508575102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerbai F, Giovannini MG, Melani C, Enz A, Pepeu G. N1phenethyl-norcymserine, a selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor, increases acetylcholine release in rat cerebral cortex: a comparison with donepezil and rivastigmine. Eur J Pharmacol. 20071;572:42–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann J, Kiewert C, Duysen EG, Lockridge O, Greig NH, Klein J. Excessive hippocampal acetylcholine levels in acetylcholinesterase-deficient mice are moderated by butyrylcholinesterase activity. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Alloza M, Gil-Bea FJ, Diez-Ariza M, Chen CP, Francis PT, Lasheras B, Ramirez MJ. Cholinergic-serotonergic imbalance contributes to cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Alloza M, Zaldua N, Diez-Ariza M, Marcos B, Lasheras B, Javier Gil-Bea F, Ramirez MJ. Effect of selective cholinergic denervation on the serotonergic system: implications for learning and memory. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1074–1081. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240469.20167.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M STAR*D Study Team. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith GS, Kramer E, Ma Y, Hermann CR, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Eidelberg D. Cholinergic modulation of the cerebral metabolic response to citalopram in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:392–401. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozzini L, Chilovi BV, Conti M, Bertoletti E, Zanetti M, Trabucchi M, Padovani A. Efficacy of SSRIs on cognition of Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with cholinesterase inhibitors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:114–119. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rockwood K, Walsh R, Martin E, Darvesh S. Potentially pro-cholinergic effects of medications commonly used in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh R, Martin E, Darvesh S. A versatile equation to describe reversible enzyme inhibition and activation kinetics: Modeling β-galactosidase and butyrylcholinesterase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Featherstone RM. A New and Rapid Colorimetric Determination of Acetylcholinesterase Activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Copeland RA. Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis. 2. Wiley-VCH; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fylstra D, Lasdon L, Watson J, Waren A. Design and use of the microsoft excel solver. Interfaces. 1998;28:29–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silver A. The Biology of Cholinesterases. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khanin R, Parnas H, Segel L. Diffusion cannot govern the discharge of neurotransmitter in fast synapses. Biophys J. 1994;67:966–972. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80562-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smart JL, McCammon JA. Analysis of synaptic transmission in the neuromuscular junction using a continuum finite element model. Biophys J. 1998;75:1679–1688. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77610-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Land BR, Salpeter EE, Salpeter MM. Acetylcholine receptor site density affects the rising phase of miniature endplate currents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3736–3740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darvesh S, Martin E, Walsh R, Rockwood K. Differential effects of lipid lowering agents on human cholinesterases. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.