Abstract

We have identified a point mutation in Npc1 that creates a novel mouse model (Npc1nmf164) of Niemann–Pick type C1 (NPC) disease: a single nucleotide change (A to G at cDNA bp 3163) that results in an aspartate to glycine change at position 1005 (D1005G). This change is in the cysteine-rich luminal loop of the NPC1 protein and is highly similar to commonly occurring human mutations. Genetic and molecular biological analyses, including sequencing the Npc1spm allele and identifying a truncating mutation, confirm that the mutation in Npc1nmf164 mice is distinct from those in other existing mouse models of NPC disease (Npc1nih, Npc1spm). Analyses of lifespan, body and spleen weight, gait and other motor activities, as well as acoustic startle responses all reveal a more slowly developing phenotype in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice than in mice with the null mutations (Npc1nih, Npc1spm). Although Npc1 mRNA levels appear relatively normal, Npc1nmf164 brain and liver display dramatic reductions in Npc1 protein, as well as abnormal cholesterol metabolism and altered glycolipid expression. Furthermore, histological analyses of liver, spleen, hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum reveal abnormal cholesterol accumulation, glial activation and Purkinje cell loss at a slower rate than in the Npc1nih mouse model. Magnetic resonance imaging studies also reveal significantly less demyelination/dysmyelination than in the null alleles. Thus, although prior mouse models may correspond to the severe infantile onset forms of NPC disease, Npc1nmf164 mice offer many advantages as a model for the late-onset, more slowly progressing forms of NPC disease that comprise the large majority of human cases.

INTRODUCTION

Niemann–Pick type C (NPC) disease is an autosomal-recessive, neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorder with a broad clinical spectrum (1,2). A classic example of NPC disease is a child of either sex developing coordination problems, dysarthria and hepatosplenomegaly during early school-age years. This is accompanied by abnormal intracellular accumulation of cholesterol and glycosphingolipids in a variety of tissues, including liver and spleen, and the progressive loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells (for reviews, see 1–3). The neurological progression of the disorder is relentless and is characterized by increasing severity of ataxia, developmental dystonia and dementia, until death supervenes, usually during the second decade of life (1,2). The gene underlying 95% of the cases of this disorder is NPC1/Npc1, which shows homology to the genes for Patched, HMG CoA reductase and SCAP (SREBP cleavage activating protein) (4,5). Functional analysis of NPC1, a multipass transmembrane protein containing a sterol-sensing domain, suggests that it is involved in late endosomal lipid sorting and trafficking (6–8).

Efforts to develop eukaryotic and animal models of NPC disease have included analyses of NPC1 homologs in yeast (9), Caenorhabditis elegans (10) and Drosophila melanogaster (11), which have complemented investigations in established feline (12), canine (13) and rodent models, including the Npc1spm mouse (14,15) containing a previously unidentified mutation and the well-characterized, widely used Npc1nih mouse. The Npc1nih model was first described by Pentchev et al. (16) and found to store cholesterol by Morris et al. (17), Shio et al. (18) and Bhuvaneswaran et al. (19). In these mice, an active mouse retroposon inserted 1100 bp of DNA and deleted 800 bp of the Npc1 gene (4). This created a frame shift, effectively ‘knocking out’ the Npc1 gene (4), and results in decreased recombination at the site (20). Thus, there is only a small amount of the apparently truncated Npc1 mRNA (21) and a total lack of NPC1 protein in the homozygous-recessive mice. The relatively early-onset, rapid progression of NPC disease in these mice may make them a more suitable model for the severe infantile onset forms of this disorder rather than the late-onset, mildly progressing forms of the disease that are much more common (1,2). In addition, human mutations are mostly missense, with only ∼5% of patients homozygous for truncating mutations (22). This, coupled with other experimental limitations of Npc1nih mice, has left a need for improved experimental models for investigating this disorder.

Here we describe the discovery and characterization of a novel subline of mice (Npc1nmf164) with a point mutation in the Npc1 gene that corresponds to a single amino acid change (D1005G) in the NPC1 protein. The mutation corresponds to a site in the large cysteine-rich luminal loop of the NPC1 protein, where approximately one-third of the identified human mutations have been located (2,22). We have used genetic, molecular biological, biochemical, histological and behavioral approaches to establish that Npc1nmf164 mice are distinct from other current mouse models of NPC disease and to show that although these mice display many of the hallmarks of this disorder, they exhibit a late-onset, milder disease progression than in Npc1nih mice. The location of this mutation to a region where a high proportion of human mutations are found, coupled with the late–onset, slower disease progression, make Npc1nmf164 mice a valuable model for understanding this disorder and for developing treatments for the most commonly occurring, late-onset forms of human NPC disease.

RESULTS

Mutational analysis

Identification of a new allele of Npc1

The Npc1nmf164 allele was generated in a large-scale ethyl-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis of C57BL/6J mice performed at the Jackson Laboratory. The program was designed to identify recessive, induced mutations in mice that presented with neurological phenotypes. The nmf164 mice were first noted for their overt, age-dependent ataxia. Subsequent histological examination of tissues as part of a full necropsy screen revealed abnormal lipid storage in the spleen and liver and a loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells, all hallmarks of NPC disease. The inheritance of the nmf164 mutation was consistent with a single-gene, recessive mutation. Allelism with Npc1 was established by a failure to complement both the Npc1nih allele and the Npc1spm allele. We have, therefore, designated this mutation as a new allele of Npc1 and named it Npc1nmf164.

Identification of a mutation in the Npc1 gene of Npc1nmf164 mice

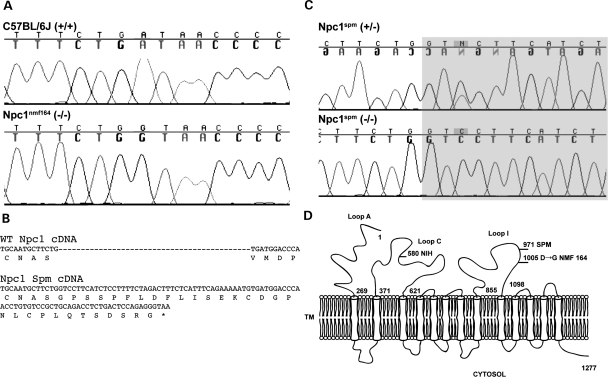

The mutation in the Npc1nmf164 allele was identified by sequencing the entire coding sequence of Npc1 cDNA, generated by reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of overlapping products. The mutation is a single base pair change, A to G, in codon 1005, changing an aspartate to glycine in Loop I of the protein, between the eighth and ninth (of 13) transmembrane domains. In genomic DNA, this codon is contained in exon 20 (out of 25), and the presence of the mutation and its segregation with the phenotype were confirmed by sequencing this exon amplified from genomic DNA (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Npc1 alleles in the mouse. (A) Sequencing cDNA from strain-matched control (C57BL/6J) and homozygous Npc1nmf164 mice revealed an A–G point mutation, resulting in a glycine (GGT) rather than an aspartate (GAT) at amino acid #1005. (B) The Npc1spm point mutation results in a splicing defect that retains 43 base pairs of intron 19 in the cDNA, resulting in a frame shift, 30 novel amino acids and premature termination. (C) Sequencing genomic DNA of the Npc1spm heterozygous and homozygous mice (C57BL/Kahles background) revealed an A–C point mutation in the third base of intron 19, the shaded region is intron sequence. Note that the sequence of the heterozygote is from the complementary strand. (D) The protein topology of NPC1. The 13 transmembrane protein is represented, the cytosolic domains are down and the luminal domains are up; numbers indicate amino acid positions. The positions of three mouse mutations (Npc1nih, Npc1spm and Npc1nmf164) are noted.

The Npc1nmf164 allele is distinct from the Npc1nih and Npc1spm models of NPC disease. The single amino acid change identified in the Npc1nmf164 allele is likely to confer a partial loss of function to the NPC1 protein. Consistent with this, the phenotype of the Npc1nmf164 homozygous mice has a later onset than the well-characterized Npc1nih null allele (as described below). To continue this genotype/phenotype correlation, we also identified the mutation in the Npc1spm allele, which has a phenotypic onset and severity similar to Npc1nih homozygotes (14,15). Sequencing the coding sequence of cDNA amplified from these mice, as above for the nmf164 allele, revealed a 43 base pair insertion following codon 971 (Fig. 1B). This insertion results in a frame shift and 30 novel amino acids followed by a premature termination codon. This truncation is also in Loop I of the protein. The 43 base pair insertion in the cDNA is retained intron sequence, appended to the 3′ end of exon 19. This retention is caused by a single A to C mutation in the third base of the intron (Fig. 1C), apparently destroying the splice donor and retaining the intron sequence until a cryptic splice site 43 bases into the intron successfully splices to exon 20. No evidence of any wild-type splicing from exon 19 to 20 was found in Npc1spm transcripts. We, therefore, conclude that both the Npc1nih and Npc1spm alleles are nulls based on their phenotypic similarity and the severe impact of the mutations on NPC1 protein structure (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the Npc1nmf164 allele is likely to cause a partial loss of function based on the delayed onset of the phenotype (as described below) and the milder single amino acid substitution.

Npc1nmf164 mutant mice have relatively normal levels of Npc1 mRNA, but dramatically reduced levels of Npc1 protein. To further understand the consequences of the mutation in the Npc1 gene in Npc1nmf164 mice, the levels of Npc1 mRNA and the Npc1 protein were evaluated in wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice.

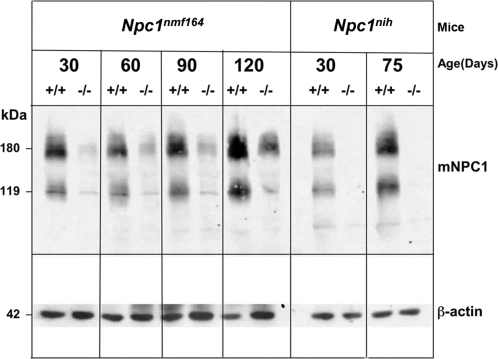

Western blot analyses were used to compare the levels of Npc1 protein in liver tissue from wild-type and mutant Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164mice at ages between 30 and 120 days (Fig. 2), using a previously developed antibody for NPC1/Npc1 (6). As shown, when compared with litter-matched wild-type controls, there was a dramatic reduction in the level of Npc1 protein in the mutant Npc1nmf164 mice at all ages examined. Although the levels of protein were low (10–15% of wild-type), the fact that they were detectable was in contrast to the total lack of detectable Npc1 protein in the tissues from Npc1nih mutant mice at similar ages and under similar conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Npc1nmf164 mutant mice have substantially reduced levels of NPC1 protein. Western blot analysis of 200 μg samples of protein lysates prepared from the livers of wild-type and mutant Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mice shows the dramatically reduced levels of Npc1 (shown as signals at 180 and 119 kDa) in the homozygous mutant mice. In contrast to the lack of detectable Npc1 in the Npc1nih mutants, there are low, but detectable (10–15% wild-type) levels of Npc1 in the Npc1nmf164 mutants. The blot was probed with an anti-peptide antibody specific for NPC1 which cross-reacts with Npc1 (courtesy Dr W. Garver) and then stripped and re-probed with an antibody specific for β-actin (as a ‘loading control’ for indication of the variation in the amount of total protein analyzed in each sample).

To determine whether the dramatic decrease in the levels of Npc1 protein in the mutant Npc1nmf164 mice could be explained by corresponding differences in Npc1 mRNA levels, mRNA was isolated from brain and liver tissue of wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice at 60 and 90 days and was analyzed in qRT-PCR assays using primer sets similar in their ability to detect wild-type and mutant Npc1 sequences (see Materials and Methods). The average cycle threshold of detection (Ct) of the wild-type (17.1 ± 0.9, n= 3) and mutant (17.2, n= 2) sequences in the liver samples from 60-day-old mice were effectively the same, as were the Ct values for the wild-type (16.7 ± 0.7, n= 3) and mutant (16.5, n= 2) sequences in the brain samples collected at this age. Similar results were observed for tissues harvested at 90 days, with similar Ct values obtained for wild-type (18.3, n= 2) and mutant (17.9, n= 2) liver and for wild-type (16.1, n= 2) and mutant (16.1, n= 2) brain tissue. Together, the results from these two different ages and tissues suggest that there are similar levels of Npc1 mRNA in wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164mice. As a result, reduced levels of gene expression and steady-state mRNA do not appear to be an explanation for the dramatic reduction in Npc1 protein observed in the mutant Npc1nmf164animals.

Analysis of endoplasmic reticulum stress and protein misfolding

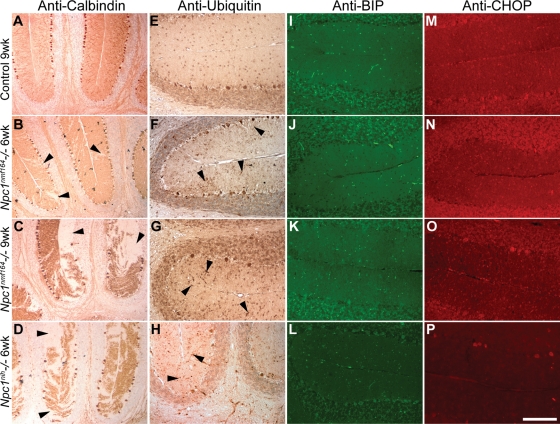

Recent results using fibroblasts from NPC patients suggest that decreased NPC1 protein levels are the result of instability caused by misfolding and impaired intracellular trafficking (23). We examined this possibility in vivo to determine whether protein misfolding could be contributing to cerebellar Purkinje cell degeneration. The Npc1nmf164 mice were examined at 6 and 9 weeks of age, and compared with 6-week-old Npc1nih mice (three mutants and three wild-type littermate controls examined at each time point). Sagittal cerebellar sections were stained with an antibody directed against calbindin to assess Purkinje cell loss (Fig. 3A–D). At 6 weeks, only a few Purkinje cells were lost in Npc1nmf164 mice, whereas at 9 weeks the loss was more pronounced. In contrast, at 6 weeks, theNpc1nih mice were comparable to the 9-week-old Npc1nmf164 mice. Staining for ubiquitin revealed immunoreactive Purkinje cell dendrites in the molecular layer of the cerebellum in both mutant genotypes, presumably marking cells that were degenerating (Fig. 3E–H). Staining for BiP (immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein, GRP78) and CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein, GADD153), two components of the misfolded protein response pathway, did not reveal intensities that differed from controls in the Npc1nmf164 mice at either time point (Fig. 3I–P). Occasionally, strongly reactive cells were observed, but fluorescence intensities in exposure-matched images from slides processed in parallel did not reveal any increase in staining in the mutant samples in either Purkinje cell bodies or in the dendrites in the molecular layer when compared with the controls. Furthermore, similar results were obtained with the Npc1nih mice, which are null for Npc1 and do not have any misfolded NPC1 protein. Therefore, any apparent reactivity is probably a generic consequence of neurodegeneration rather than a specific effect caused by misfolded NPC1. Although no upregulation of markers of the unfolded protein response was observed by immunocytochemistry, the NPC1nmf164 protein may still be degraded through this pathway, but even a general upregulation of the unfolded protein response was not induced to a level detectable by this method.

Figure 3.

Markers of the misfolded protein response in cerebellar Purkinje cells. (A–D) Purkinje cell loss (arrowheads) was assessed by calbindin staining in control, 6- and 9-week-old Npc1nmf164 mice and 6-week-old Npc1nih mice. (E–H) Ubiquitin accumulation was observed in the dendrites of degenerating Purkinje cells in both mutant genotypes (arrowheads). No increase in BiP (I–L) or CHOP (M–P) was observed. Brightly stained structures in I–L are blood vessels that react non-specifically with the secondary antibody. Images for each genotype are from the same mouse. The scale bar (in panel P) represents 290 µm for A–D, and 145 µm for D–P.

General phenotype

The delayed disease progression influences the breeding characteristics of the Npc1nmf164 mice. Npc1nmf164 mice have litters of 1–10 pups, with heterozygous parents having an average of 4–5 pups per litter (4.94 ± 0.4, n= 42). Interestingly, the disease progression in Npc1nmf164 mice is mild enough that breeding pairs of homozygous mutants can produce several litters before the severity of the disease interferes with their ability to reproduce. This is in contrast to Npc1nih mice and is of tremendous experimental advantage, not only in making it possible to generate litters in which all of the pups are homozygous mutants with respect to Npc1, but also in providing a means of overcoming the relative paucity of homozygous mutants obtained from heterozygous breeding pairs. In regard to the latter, the segregation ratio of Npc1nmf164 on its C57BL/6J background shows a marked deficiency of homozygotes—13% (53:107:24) instead of the expected 25%. This is comparable to Npc1nih maintained on the BALB/cJ background where, over the past decade, in several of our laboratories, the homozygous mutants have comprised 16–18% of the pups born (24) (R. Erickson, unpublished observations).

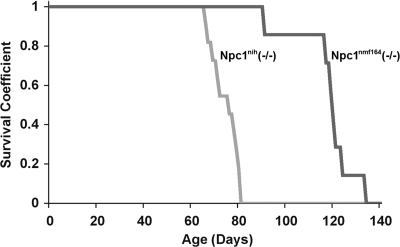

The Npc1nmf164 homozygotes that are produced survive longer than the Npc1nih homozygotes (Fig. 4). The average lifespan of the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice (112 ± 4 days, n= 12) is significantly (P < 0.05) longer than that of the Npc1nih mutant mice (74.1 ± 1.7 days, n= 23). This difference is even more notable when the genetic backgrounds of the two strains of mice are considered, and we predict that the Npc1nmf164 homozygous mutants, which are on a C57BL/6J genetic background, would survive even longer if moved to the BALB/cJ background of the Npc1nih mice, since Npc1nih homozygotes have a significantly shortened survival on the C57BL/6J background [48.1 ± 5.1 (21)].

Figure 4.

Survival curves of Npc1nmf164 homozygotes maintained on the C57BL/6J background compared with Npc1nih homozygotes on the BALB/cJ background. Kaplan–Meier plot of mouse survival for mutant Npc1nih (gray line) and Npc1nmf164 (black line) mice.

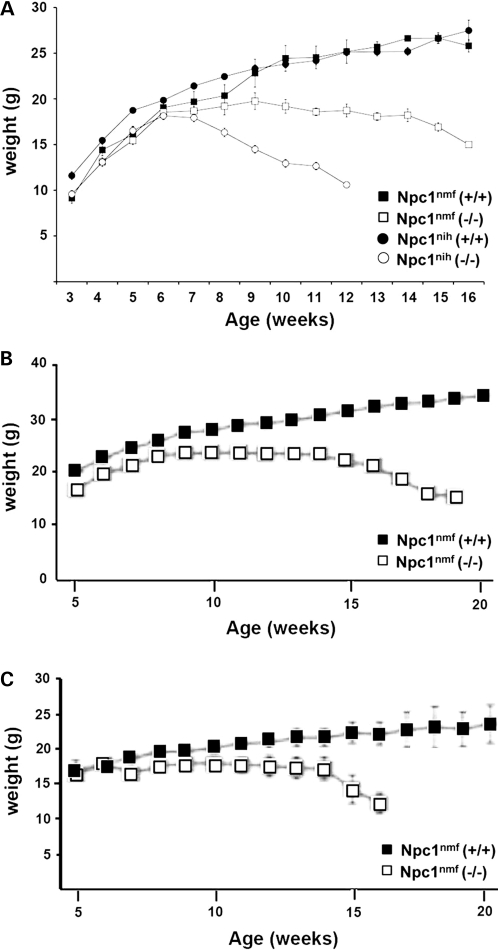

The growth characteristics of Npc1nmf164 mice are distinct from those of Npc1nih mice. As shown (Fig. 5A), although Npc1nih mutants exhibited a noticeable weight loss in comparison to their wild-type counterparts at ∼6–7 weeks, Npc1nmf164 mutants did not exhibit weight loss or differ noticeably from wild-type Npc1nmf164 mice until ∼3 weeks later, at 9–10 weeks. Not only does the onset of weight loss occur later, but the rate of weight loss in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice is also more gradual than in Npc1nihmutant mice (Fig. 5A). This occurs both in males and females (Fig. 5B and C). Thus, the longer survival of this Npc1nmf164 point mutant is reflected in the delayed loss of weight, which occurs between 10 and 14 weeks of age, well past the survival of Npc1nih homozygous mutant mice.

Figure 5.

The weight loss in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice occurs with a late-onset, slower progression than in Npc1nih mutant mice. (A) Wild-type Npc1nmf164 (n= 27) and Npc1nih (n= 43) mice, and homozygous mutant Npc1nmf164 (n= 10) and Npc1nih (n= 50) mice of both sexes were weighed weekly. As shown, weight loss in the Npc1nih mice began at ∼6–7 weeks, whereas in the Npc1nmf164 mice the onset of the weight loss in the homozygous mutants was not evident until ∼9–10 weeks, and the subsequent time course was slower. (B) Weight loss of wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 males. (C) Weight loss of wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 females.

Somatic phenotype

Abnormal lipid accumulation in systemic organs of Npc1nmf164mutant mice

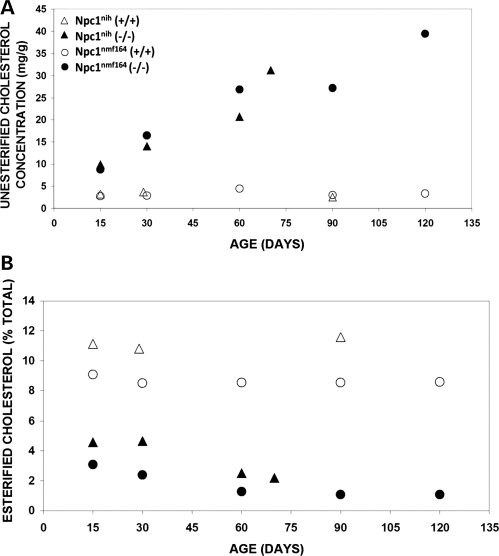

A major hallmark of NPC disease in mammals is a complex but characteristic pattern of lipid accumulation in liver and spleen that includes the progressive accumulation of unesterified cholesterol, sphingomyelin, bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (LBPA) and several glycosphingolipids (for a review, see 1,3).To evaluate cholesterol in Npc1nmf164 mice, standard gas chromatography/mass spectrometry procedures (25) were used to obtain quantitative measurements of esterified and unesterified cholesterol in liver tissue from wild-type and mutant mice between 15 and 120 days of age (see Materials and Methods). As shown, the relative levels of unesterified cholesterol in mutant Npc1nmf164 mice increased with age and were higher than the levels in wild-type mice at all ages examined, so that at older ages they were 10–20 times the levels measured in the wild-type mice (Fig. 6A). In contrast, relative levels of esterified cholesterol in the liver tissue of the mutant mice were 3–10 times lower than those observed in wild-type mice and remained low at all ages examined (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Cholesterol metabolism is abnormal in the liver of Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. (A) Concentration of unesterified cholesterol in Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mutant mice is abnormal in comparison to wild-type mice. As shown, the levels of unesterified cholesterol remained low in the wild-type mice throughout the ages examined. In contrast, in mutant mice the levels of unesterified cholesterol were elevated even in the youngest age examined, and they continued to show similar increases throughout the period of time that was examined. (B) The percent of esterified cholesterol is abnormal in Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mutant mice in comparison to wild-type mice. The levels of esterified cholesterol in the mutant mice were relatively low throughout the time period examined.

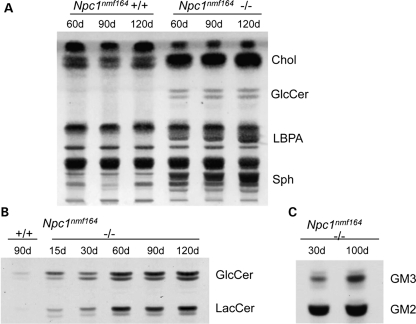

Further examination of the total lipid profiles of liver tissue in the Npc1nmf164mutant mice at 60, 90 and 120 days of age (Fig 7A) revealed striking differences from those in age-matched wild-type mice, with not only a massive increase in unesterified cholesterol, but also a progressive accumulation of sphingomyelin and LBPA as well as a marked accumulation of glucosylceramide over this time period. Specific analysis of the neutral glycosphingolipids (Fig. 7B), which are normally only present in minute amounts in mouse liver, showed that glucosylceramide and lactosylceramide concentrations were already elevated in 15-day-old mice and underwent notable increases during aging. In the liver of littermate wild-type mice, like in the Npc1nih mice, GM2 is the predominating ganglioside, although it only constitutes a minute component. In the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice, however, liver tissue accumulates large amounts of GM2 and some GM3 (Fig. 7C). Thus, taken together, the data demonstrate that in terms of the lipid profile in liver, the Npc1nmf164 mouse displays the characteristic NPC profile and it does not differ greatly from published results for both the Npc1nih and Npc2 mutant mice analyzed using the same methods (26).

Figure 7.

Lipid abundance in the liver is abnormal in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. (A) Total lipids in the liver of wild-type and homozygous mutant Npc1nmf164 mice. As shown, there are abnormally elevated levels of cholesterol (Chol), glucosylceramide (GlcCer), lyso-bis-phosphatidic acid (LBPA) and sphingomyelin (Sph) in the homozygous mutants. (B) The neutral glycolipids glucosylceramide (GlcCer) and lactosylceramide (LacCer) and (C) the GM2 and GM3 gangliosides also accumulate in the liver of homozygous mutant Npc1nmf164 mice.

In addition to the biochemical analyses, histological analyses also provided evidence of abnormal lipid accumulation in the liver and spleen of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. The lipid accumulation in vacuole-like inclusions is observed in both tissues by 60 days of age and is readily detected in mice that are 90 days old (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1).

Finally, quantitative analysis revealed an enlargement of the spleen in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice that occurs at later ages than it does in Npc1nih mutant mice. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly are usually observed in human NPC patients (for reviews, see 1–3). Enlarged spleen and liver have not been previously reported for Npc1nih mutant mice, however, perhaps due to the absence of detailed analysis and to the rapid time course of the disorder in these animals, including the rapid onset of generalized wasting and loss of body weight. As shown in Table 1, however, detailed examination of spleen weight in the wild-type and mutant mice as a function of age and genotype provides the first evidence of an abnormal increase in spleen weight in both Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mutant mice. This was not evident in either Npc1nmf164 or Npc1nih mice at 30 days of age. A significant (P < 0.004) increase in spleen weight was apparent in Npc1nih mutant mice when they were 40 days old; however, this was still detectable in 50-day-old homozygotes. In 60-day-old mice, the spleen in the Npc1nih mutant is no longer significantly larger than in the wild-type mice, although by that age the generalized wasting and loss of overall body weight characteristic of the disease has become apparent (Fig. 5). The spleen in 60-day-old Npc1nmf164 mutant mice is also not significantly larger than in wild-type mice of similar age, but by 90 days the spleen in the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice is significantly (P < 0.05) larger than in age- and litter-matched wild-type mice (Table 1). Thus, the enlargement occurs in both strains of mice, but occurs later in the Npc1nmf164 mice.

Table 1.

Spleen weight in wild-type and mutant Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mice between 30 and 120 days of age

| Age (days) | Genotype | Weight (±SD) (mg) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | Npc1nih (+/+) | 128.4 ± 50 (n= 15) | 0.671 |

| Npc1nih (−/−) | 138.5 ± 73 (n= 13) | ||

| Npc1nmf164 (+/+) | 71.5 ± 24 (n= 7) | 0.243 | |

| Npc1nmf164 (−/−) | 55.7 ± 17 (n= 5) | ||

| 40 | Npc1nih (+/+) | 104.1 ± 14 (n= 9) | 0.004*** |

| Npc1nih (−/−) | 128.9 ± 18 (n= 9) | ||

| 50 | Npc1nih (+/+) | 89.5 ± 11 (n= 10) | 0.027*** |

| Npc1nih (−/−) | 107.4 ± 21 (n= 10) | ||

| 60 | Npc1nih (+/+) | 98.1 ± 12 (n= 24) | 0.001*** |

| Npc1nih (−/−) | 82.2 ± 17 (n= 26) | ||

| Npc1nmf164 (+/+) | 68.1 ± 9 (n= 8) | 0.606 | |

| Npc1nmf164 (+/+) | 64.6 ± 2 (n= 3) | ||

| 90 | Npc1nmf164 (+/+) | 81.6 ± 16 (n= 7) | 0.011*** |

| Npc1nmf164 (−/−) | 114.6 ± 23 (n= 6) |

***Statistically significant at P < 0.

Foamy macrophages accumulate in the lungs of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice

We have previously characterized the pulmonary disease in the Npc1nih mouse model by histology, pulmonary function tests and biochemical assays (27). Histological analyses of the Npc1nmf164 mice showed marked accumulation of foamy macrophages, but no alveolar proteinosis (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). In addition, trichrome staining suggests an increase in collagen deposition, which was also found in the Npc1nih mouse model (27).

Neuropathology

Progressive loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice

The loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells is often a prominent feature of NPC1 disease in humans (1–3). The progressive loss of these cells is also one of the hallmark features of the previously described mouse models of NPC1 disease, with Purkinje cell degeneration and loss detected by 28–40 days and very pronounced by 60 days of age (28–30). To further study the degree of Purkinje cell loss in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice, sagittal sections of cerebellar tissue were obtained from mice that were between 15 and 90 days old (P15–P90). The cerebellar sections were fixed, and Purkinje cells were detected using an antibody specific for calbindin. As shown in Figure 3A–D and Supplementary Material, Figure S3, there is a progressive loss of Purkinje cells in the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. Specifically, although there is no noticeable loss of Purkinje cells at P15, there are early signs of loss by P30. Between P30 and P60, the amount of Purkinje cell loss increases, although in contrast to reports for Npc1nih mutant mice (28–30), at P60 the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice still have most of their Purkinje cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). Between P60 and P90, however, the Purkinje cell loss in these mice is extensive, and by P90 very few Purkinje cells can be found in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

As an additional indication of Purkinje cell loss in the mutant mice, we used quantitative real-time PCR analysis to evaluate Purkinje-cell-specific gene expression in the cerebellum of wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice. Specifically, the levels of mRNA for calbindin and SERCA 3A, which in the cerebellum are expressed solely in the Purkinje cells (31), were measured in cerebellar tissues from Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice between 30 and 90 days of age. Using this as an indirect indication of Purkinje cell survival, we see an age-dependent decrease in the expression of both these transcripts in the Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 homozygotes relative to their respective wild-type controls (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Although there is a relative decrease in the level of expression of both these transcripts in both mutants, the decrease appears to occur more slowly in the Npc1nmf164 mice, as suggested by the higher levels of expression at 60 days of age and the still detectable levels of calbindin and SERCA 3A mRNAs in 90-day-old mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4).

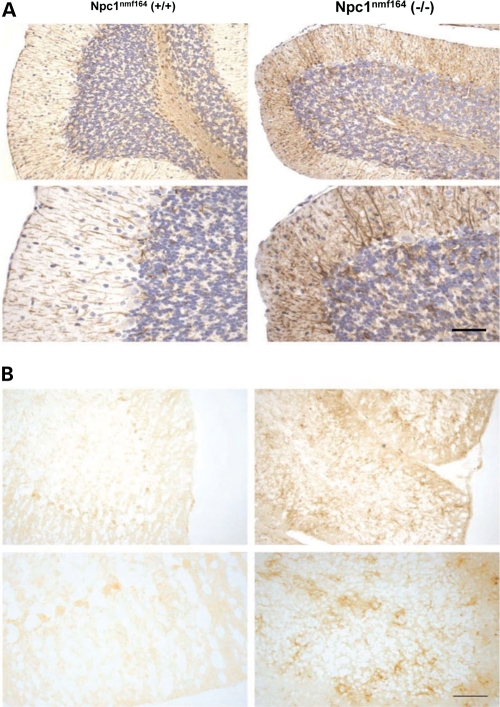

Increased astrocyte and microglial activation in the cerebellum of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice

NPC1 disease in humans includes pathological alterations in both astrocytes and microglia (for a review, see 3), and in the Npc1nih mouse model of NPC disease the postnatal development of inflammation in mutant mice has been shown to include increases in microglia and astrocyte activation in the brain (32,33). To determine whether these pathological changes also occur in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice, sagittal sections of cerebellar tissue were incubated with either antibodies specific for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (34) to label activated astrocytes, or with antibodies specific for the surface integrin CD11b/Mac-1 (35) to label microglia. As indicated by the increase in GFAP labeling (Fig.8A), there is an increase in astrocyte activation in the cerebellum of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. Consistent with this, there is also an increase in microglia in the cerebellum of the homozygous mutant mice, as indicated by an increase in CD11b labeling (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Enhanced astrocyte and microglial activation in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. Images from sagittal tissue sections of the cerebellum from 120-day-old wild-type (left column) and mutant (right column) Npc1nmf164 mice labeled with (A) an antibody specific for GFAP or (B) an antibody specific for the microglial marker cd11b. Tissue sections shown in parts A and B are from different mice. In (A), the increased levels of the brown reaction product in the sections from the homozygous mutant mice indicate an increase in GFAP expression and enhanced levels of astrocyte activation in the mutant mice. In (B), the increase in CD11b labeling (right column) suggests an increase in microglial activation. The scale bars (bottom right in parts A and B) represent 200 μm.

Abnormal cholesterol accumulation in neurons of Npc1nmf164mutant mice

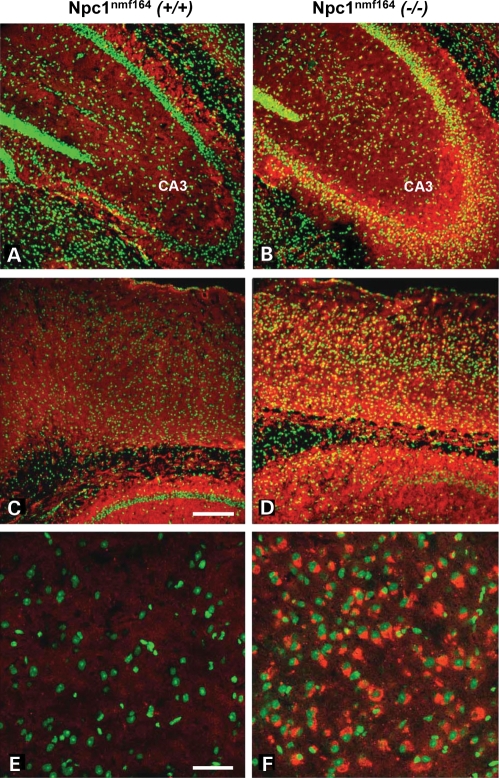

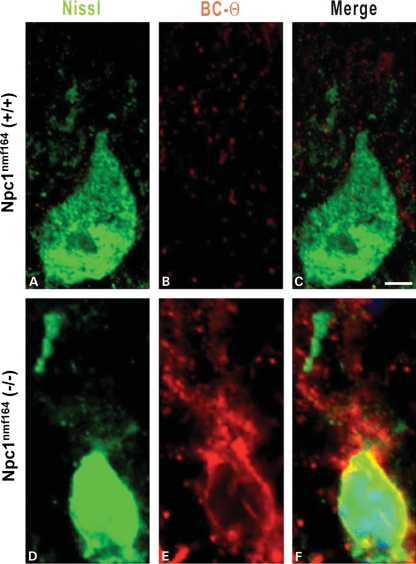

Coronal tissue sections from the hippocampus of 120-day-old wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164mice that were co-labeled with the cholesterol-labeling reagent BC-Θ (36,37) and Nissl stain show the selective accumulation of cholesterol in the neuronal cell bodies in the CA3 region of the hippocampus of the mutant, but not wild-type, mice (Fig 9A and B). Similarly stained coronal tissue sections from the cortex of 120-day-old wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice also show the selective accumulation of cholesterol in neuronal cell bodies of the mutant, but not wild-type, mice (Fig 9C and D). Higher magnification images (Fig. 9E and F) show the accumulation of cholesterol in individual cells of the mutant cortex. A similar pattern was also found in the cerebellum of 120-day-old wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice that were also co-labeled with BC-Θ and Nissl stain. The results clearly show the selective accumulation of cholesterol in the Purkinje cells of the mutant, but not wild-type, mice (Fig 10). Biochemical analyses of brain tissue did not reveal an overall increase of cholesterol levels (data not shown), in accordance with the findings in other murine models and in the human patients (1,2,38).

Figure 9.

Abnormal cholesterol accumulation in the brain of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. Confocal images of coronal tissue sections from the hippocampus (A, B) and cortex (C–F) of 120-day-old wild-type (left column) and mutant (right column) Npc1nmf164 mice that were co-labeled with the cholesterol-labeling reagent BC-Θ (red) and Nissl stain (green) show the selective accumulation of cholesterol in the mutant, but not wild-type, mice. Higher magnification images (E–F; bottom row) show the accumulation of cholesterol in individual cells of the mutant cortex. Scale bar in (C) represents 200 μm and in (E) represents 50 μm.

Figure 10.

Abnormal cholesterol accumulation in cerebellar Purkinje cells of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. (A–F) Confocal images of Purkinje cells from the cerebellum of 120-day-old wild-type (A–C) and mutant (D–F) Npc1nmf164 mice that were co-labeled with the cholesterol-labeling reagent BC-Θ (red) and Nissl stain (green) show the selective accumulation of cholesterol in the Purkinje cells of the mutant, but not wild-type, mice. The scale bar in (C) represents 10 μm.

Abnormal accumulation of gangliosides in brain of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice

Previous studies have demonstrated that increases in the levels of GM2 and GM3 gangliosides constitute one of the main lipid abnormalities in the NPC brain (1,26,38–40). As illustrated in Fig 11A, this abnormality occurs in the Npc1nmf164 mouse, and there are striking differences between the levels of these gangliosides in the wild-type and mutant animals. To investigate this further, quantitative studies were conducted in Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice between 15 and 120 days of age (Fig. 11B and C). In wild-type animals, the proportion of GM3 and GM2 in the brain was very low and remained essentially constant during the entire period. In the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice, however, GM2 ganglioside levels were already very high in the 15-day-old mice and stayed similarly elevated for the duration of the time period analyzed. The levels of GM3 started to increase around the age of 15 days, also with a marked inter-individual variation, and showed a progressive increase until at least 90 days of age but were possibly lower those found in Npc1nih brains at comparable ages.

Figure 11.

Gangliosides GM2 and GM3 accumulate in the brain of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. (A) The total ganglioside profiles demonstrate elevated levels of GM2 and GM3 gangliosides in the brain of Npc1nmf164 mutant mice as early as 15 days of age. (B) The levels of GM2 and GM3, expressed in mol% of the total gangliosides, are elevated up to 10–20 times in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice compared with wild-type mice, and are similar to those observed in Npc1nih mutant mice.

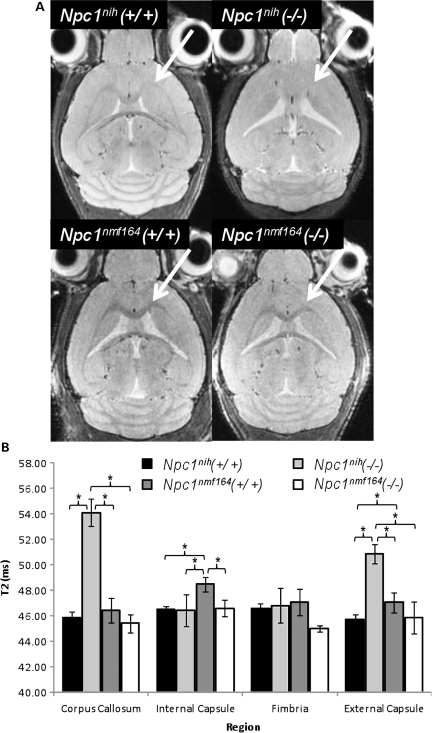

Analysis of myelination in Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice using magnetic resonance imaging

We have previously shown marked decreases in myelination in the Npc1nih model using diffusion tensor imaging by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (41). We have now used T2-weighted MRI, which disclosed enlarged ventricles in the wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice, but little decrease in myelination in the mutants relative to the wild-type mice (Fig. 12A). This was carefully quantified in four regions of interest (ROIs) (Supplementary Material, Figs S5 and S6). As shown in Figure 12B, the Npc1nmf164 mutants were not statistically different from the wild-type controls for the T2 signal (which represents water replacing fat), whereas Npc1nih mutant mice show a very significant increase in this signal in the corpus callosum (CC) and external capsule (EC) and internal capsule (IC).

Figure 12.

MRI of wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice. (A) White matter areas of the CC and EC (arrows) appear darker than the surrounding grey matter tissue on in vivo T2-weighted MRI images. A lack of contrast between white and grey matter is evident in the Npc1nih mouse brain but not in that of the Npc1nmf164. (B) Results of quantitative T2 measurements in the studied regions of white matter in the CC, internal and EC, and FI. Error bars denote measurement standard deviations (*P < 0.05). All mice were 9–10 weeks of age.

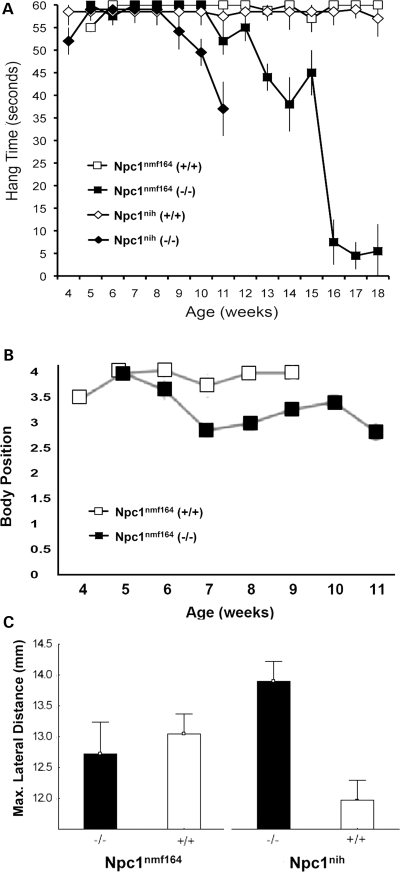

Changes in motor behavior in the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice

We used four tests of motor coordination to evaluate wild-type and mutant Npc1nmf164 mice. In the first test, the time the mouse could cling to an inverted cage lid was evaluated as an indication of strength and motor coordination. We observed a decrease in the strength and motor capabilities of Npc1nih mutant mice several weeks before Npc1nmf164 mutant mice displayed diminished capabilities (Fig. 13A). As shown, soon after testing began at 4–5 weeks of age, the mice from both sublines became proficient at this task and all were able to successfully complete the test for several weeks. The Npc1nih mutant mice continued to perform well even during advanced stages of the disease and first displayed a diminished ability to perform the task at 9 weeks of age. In contrast, Npc1nmf164 mutant mice did not show a comparable decline in their performance until 11 weeks of age, by which time a number of the Npc1nih mutant mice had already died. Using the coat hanger test, which is similar but provides an ‘agility’ score, homozygotes also showed decreased performance, although beginning earlier at ∼7 weeks (Fig 13B). In a balance beam test, which also includes a component of exploratory behavior as well as motor coordination skill, Npc1nmf164 showed a more variable performance, but were superior to the Npc1nih mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S7). Finally, analysis of gait parameters revealed less ataxia in the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice in comparison to Npc1nih mice (Fig 13C). Mice were tested at 7 weeks of age, at which time Npc1nmf164 homozygotes did not show differences from wild-type C57BL/6J littermates. However, Npc1nih homozygotes showed a greater maximal lateral displacement of each rear foot from the body midline with each stride at this age when compared with wild-type BALB/cJ littermates. Direct comparison of the two mutants is hampered by strain differences in the mice, exemplified by the differences in the two wild-type cohorts, but at later ages the Npc1nmf164 mice did eventually develop an overtly abnormal gait (data not shown).

Figure 13.

Abnormal gait and motor function occur later in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice than in Npc1nih mice. (A) Results from the ‘cage lid’ test of motor strength and coordination. As shown, all of the Npc1nih (n= 9) and Npc1nmf164 (n= 15) mice could initially performed well on the test. However, the ability of the Npc1nih mutant mice began to noticeably diminish by ∼8–9 weeks, whereas the ability of the Npc1nmf164 mutant mice did not markedly diminish until ∼10–11 weeks. (B) Coat hanger performance for Npc1nmf164 homozygotes compared with wild-type siblings. The performance of the Npc1nmf164 mutants was noticeably diminished compared with wild-type mice by 7–8 weeks. (C) Gait analysis reveals an earlier appearance of gait abnormalities and ataxia in Npc1nih mutant mice than in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. The same number of animals were tested for each genotype (n= 6). Error bars represent ±standard deviation.

Altered acoustic startle behaviors in Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice

Although an increasing number of behavioral tests have been applied to models of NPC disease (42), the acoustic startle behaviors of NPC mice have not been evaluated, despite potential advantages of such non-invasive tests that can be applied repeatedly to an individual animal. There are strain differences in acoustic sensitivity and alterations in sensitivity that occur with age in certain strains, including those with BALB/c and C57BL/6 genetic backgrounds (43,44). Thus, we were careful to compare within strains and test over a broad range of ages (29–91 days old). To further reduce variability, litter-matched wild-type and mutant mice were used whenever possible and made up >95% of the animals selected for testing (168 out of a total of 475 genotyped for possible analysis).

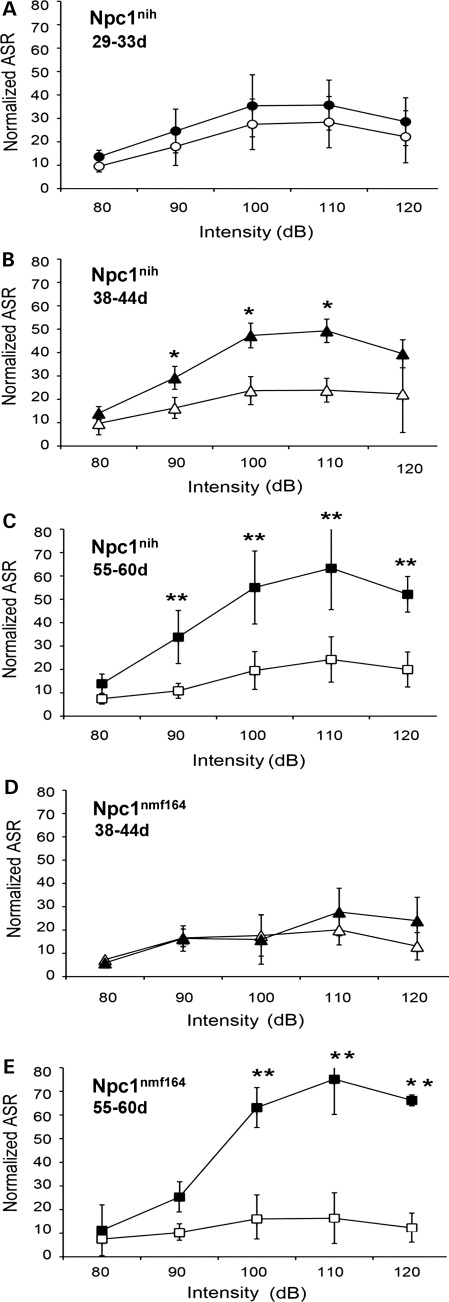

To test the range and magnitude of the responses to stimuli of different intensities, mice were placed in a Plexiglas chamber and a speaker delivered white noise startle stimuli between 80 and 120 dB. For both Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice, the wild-type and mutant mice all show increased startle amplitudes in response to increasing stimulus intensities (Fig. 14). Importantly, the peak response occurred at the same intensity (110 dB) in all cases and at all ages. At older ages, the Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mutant mice showed exaggerated startle activity. In the Npc1nih mice, the response of the homozygous mutants was similar to wild-type mice at 29–33 days old, but was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated at 38–44 and 55–60 days of age (P < 0.005) (Fig. 14B and C). In the Npc1nmf164 mice, the exaggerated responses developed later, and although there was no significant difference between wild-type and mutant mice at 38–44 days, at 55–60 days the response of the mutants was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than the response of the wild-type mice (Fig. 12D and E). The elevated response in these mice was still evident at 88–91 days of age (Supplementary Material, Fig. S8).

Figure 14.

Exaggerated acoustic startle responses (ASRs) in Npc1nmf164 mutant mice occur at a later age than in Npc1nih mutant mice. (A) At 29–33 days, the startle responses of wild-type (n= 4) and mutant (n= 3) Npc1nih mice in response to stimuli of various intensities are similar. (B) At 38–44 days, the startle responses of wild-type mutant (n= 3) Npc1nih mice in response to stimuli of various intensities are significantly increased relative to wild-type (n= 9) mice (*P< 0.05). (C) At 55–60 days, the startle responses of mutant (n= 7) Npc1nih mice in response to stimuli of various intensities are significantly increased relative to wild-type (n= 11) mice (**P< 0.005). (D) At 38–44 days, startle responses of mutant (n= 3) Npc1nmf164 mice in response to stimuli of various intensities are similar to wild-type (n= 9) mice. (E) At 55–60 days, the startle responses of mutant (n= 3) Npc1nmf164 mice in response to stimuli of various intensities are significantly increased relative to wild-type (n= 9) mice (**P< 0.005). In (A–E), the open circles, triangles and squares represent values for wild-type mice at 29–33, 38–44 and 55–60 days of age, respectively, whereas the filled circles, triangles and squares represent the values for homozygous mutant mice at 29–33, 38–44 and 55–60 days of age, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements.

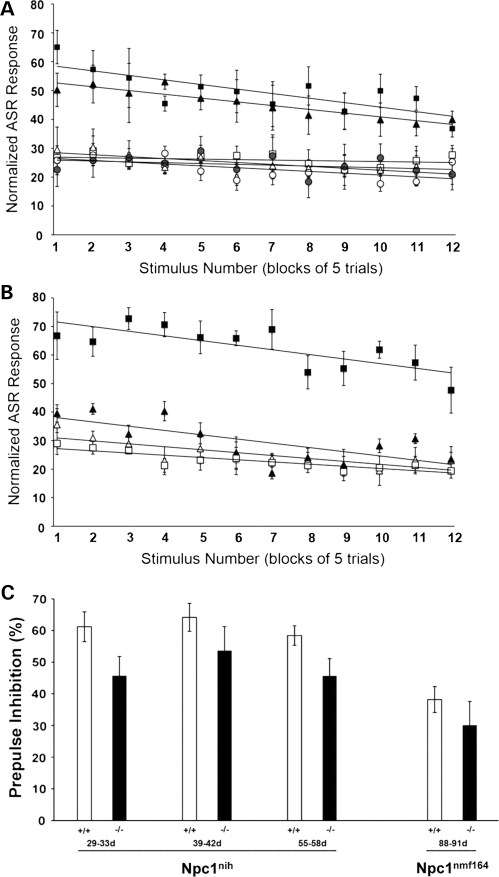

Once the intensity profiles of the mice were determined, the habituation of the mice to repeated stimuli was examined. Startle stimuli of 50 ms duration and 110 dB amplitude were presented to the mice at interstimulus interval of 15 s. As shown (Fig. 15), for both Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih, there were no notable changes in the modest rate of habituation observed as a function of age or genotype. Consistent with the intensity data, however, there were age-dependent increases in the magnitude of the response to the stimuli in the Npc1nih mutant mice at 41–44 and 55–60 days (Fig. 15A), and in the Npc1nmf164 mutants at 55–60 days, but not earlier (Fig. 15B).

Figure 15.

Habituation of the ASR in mutant Npc1nmf164 mutant mice. (A) Habituation in Npc1nih mice. Open symbols represent the magnitude of the startle response of wild-type Npc1nih mice in response to a 110 dB auditory stimulus at 29–33 days of age (open circles; n= 9), 39–44 days of age (open triangles; n= 10) and 55–60 days of age (open squares; n= 9). Solid bars represent the magnitude of the startle response of mutant Npc1nih mice in response to the stimulus at 29–33 days of age (filled circles; n= 8), 39–44 days of age (filled triangles; n= 11) and 55–60 days of age (filled squares; n= 7). Although the responses of the mutant mice at 29–33 days of age were similar to the responses observed for the wild-type mice at that age, the responses of the mutants at 39–44 and 55–60 days of age were substantially elevated. (B) Habituation in Npc1nmf164 mice. Open symbols represent the magnitude of the startle response of wild-type Npc1nmf164 mice in response to the stimulus at 39–44 days of age (open triangles; n= 8) and 55–60 days of age (open squares; n= 10). Solid bars represent the magnitude of the startle response of mutant Npc1nmf164 mice in response to the stimulus at 39–44 days of age (filled triangles; n= 5) and 55–60 days of age (filled squares; n= 3). Although the responses of the mutant mice at 39–44 days of age were similar to the responses observed for the wild-type mice at that age, the responses of the mutants at 55–60 days of age were substantially elevated. In (A and B), animals were subjected to a series of 60 stimuli. The responses were normalized to weight, and then groups of five consecutive trials were binned and the average value for those five trials was plotted. Trend lines were best fit to the data using Microsoft Excel. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements. (C) Prepulse inhibition exhibited by Npc1nmf164 and Npc1nih mice. Open bars represent the percent inhibition displayed by wild-type Npc1nih mice at 29–33 days of age (n= 10), 39–42 day of age (n= 10) and 55–60 days of age (n= 10), and wild-type Npc1nmf164 at 88–91 days of age (n= 12). Solid bars represent the extent of prepulse inhibition in mutant Npc1nih mice at 29–33 days of age (n= 6), 39–42 day of age (n= 7) and 55–60 days of age (n= 9), and mutant Npc1nmf164 at 88–91 days of age (n= 3). Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements.

Prepulse inhibition is a measure of the effect of low-intensity acoustic stimuli presented just before a startle-inducing stimulus and is an index of sensorimotor gating and pre-attentive information processing (45). To assess this in the NPC mouse models, startle stimuli (110 dB) were presented alone or preceded by a prepulse (70 dB white noise for 20 ms) at a fixed interval of 100 ms. As shown (Fig. 15C), wild-type and mutant Npc1nih mice show prepulse inhibition at all ages, with the extent of the inhibition in the mutant mice (∼45–55%) slightly reduced in comparison to that observed in the wild-type mice (∼60–65%). Similarly, the degree of prepulse inhibition in Npc1nmf164 mutants (∼30%) is blunted in comparison to their wild-type counterparts (∼40%). The slightly greater extent of prepulse inhibition in the Npc1nih mice than in the Npc1nmf164 mice is consistent with previous reports comparing prepulse inhibition in C57BL/6J and BALB/c mice (46).

DISCUSSION

NPC disease is an autosomal-recessive disorder that in 95% of human cases is associated with mutations in the NPC1 gene (1,2,22). It is characterized by abnormal intracellular accumulation of cholesterol and glycosphingolipids in a variety of tissues, including liver, spleen and brain. The neurological defects include the preferential loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells, cerebellar ataxia and reduced cognitive abilities (28–30,42), which contribute to the eventual weight loss and premature death. The lack of an effective treatment for this disorder, coupled with the increasing interest in the role of cholesterol in the brain and the growing appreciation of its potential role in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (47,48), has led to considerable interest in animal models of NPC disease.

In the early 1980s, reports of two independent mutations causing a new storage disease with neurological manifestations, now known to represent the murine equivalent of Niemann–Pick C1, appeared (14,16). The later publication (14) recognized the relationship to Niemann–Pick disease and designated the mutation as ‘sphingomyelinosis’ with the gene symbol spm (Npc1spm). The Npc1spm mutation arose spontaneously on the C57BL/Kahles strain, whereas the other mutation, referred to as Npc1nih, occurred on the BALB/c strain. Unesterified cholesterol accumulates in the liver of both strains (49,50), but the genetic background makes a great difference in the rate of accumulation (15) and in the time of onset of neurological symptoms (51). The neurological manifestations are correlated with loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (28,29). Comparative biochemical studies have established that either mutation causes the same biochemical abnormalities as in NPC disease (49,52,53). We now show that the Npc1spm mutation, like the Npc1nih mutation, is a null allele.

Thus, both these models, while valuable, are not fully comparable to the most common forms of the human disease, which are most often the result of missense, rather than null, mutations (22,39). Mutations causing NPC1 are clustered in several domains of the protein, including the patched homology domain and the cysteine-rich luminal loop of the protein. Approximately one-third of the human mutations fall in the cysteine-rich domain, as does the D1005G mutation (22). These mutations tend to cause the juvenile form of NPC1 in patients, consistent with our less severe phenotype in mice. The D1005G mouse mutation does not perfectly recapitulate a human disease allele, but it is only two amino acids away from the common P1007A allele, and the most common allele, I1061T, is in the same loop. We have not examined the effects of the mutation on the structure of the protein, but the allele shares many features of the human alleles in the same domain. Interestingly, recent work has shown the I1061T allele results in an unstable protein that is reduced by 85% in patient cell lines, but retains some cholesterol transport activity (23). These results suggest that point mutations in the cysteine-rich loop of NPC1 may be candidates for chaperone therapies to increase levels of mutant protein and thus restore at least some function. The D1005G mouse allele has a similar decrease in protein and could be used as a preclinical model for testing such therapeutic strategies. The previous Npc1nih and spm alleles would not serve this purpose because of the complete loss of protein. Thus, for studies that may directly pertain to NPC1 therapeutic testing, the nmf164 allele may represent a more accurate and useful disease model.

In our characterization of a new model (Npc1nmf164) of NPC disease, we have used genetics, molecular biology, biochemistry, histology, imaging and behavioral approaches to show not only that these mice exhibit many of the hallmark features of this disorder, but also to provide new information about NPC disease in mice: abnormal spleen enlargement, oversized brain ventricles and acoustic startle response abnormalities. The latter is of particular interest, given that auditory deficits have been reported in the majority of NPC patients when tested (54), and deficits in acoustic startle responses have been reported in other neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington's and Alzheimer's disease (55). In fact, the combination of increased auditory startle responses and modest reductions in prepulse inhibition that we observe in the Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mice has also been observed in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (56). The neuronal circuitry thought to underlie acoustic startle responses includes the vermis and medial regions of the cerebellum, pons, brainstem and cochlear nuclei (57), all brain regions known to be affected by NPC disease (58). Altered acoustic startle responses have been detected in other mouse mutants with cerebellar deficits, including those with abnormal lysosomal storage in Purkinje cells (59,60). The acoustic analyses presented here are particularly timely with regard to NPC disease, given the reported negative effects of cyclodextrin, a potentially promising NPC treatment, on auditory responses in the feline model of NPC disease (61).

The primary advantage of Npc1nmf164 mice as an experimental model is that the molecular defect and disease progression more closely reflect the majority of the human alleles than the previously described null alleles. This clearly makes the Npc1nmf164 mouse a superior choice for testing therapies. There are, however, a number of purely practical advantages as well. First, the Npc1nmf164 mice are in a C57BL/6J genetic background, which is more widely used than BALB/c (Npc1nih) or C57BL/Kahles (Npc1spm). This should reduce variability from background effects when crossing to other knockout or transgenic strains and simplify comparisons to other sets of ‘wild-type’ data. Although a more commonly used genetic background, it is distinct from that of the previous Npc1 mouse models and may facilitate genome-wide comparisons to identify modifying factors that play a role in the progression and severity of this disease. Second, the slower phenotypic progression in the Npc1nmf164 mice facilitates experimentation and analysis of NPC disease. Notably, the ability of homozygous mutants to breed and produce litters of homozygous mutant pups increases the number of mutant animals (particularly age- and litter-matched mutants) available for experiments. This advantage may be diminished to some degree, however, if there are decreases in average litter size. Despite the milder phenotype of the Npc1nmf164 allele, there does not appear to be a decrease the extent to which embryonic lethality occurs, as suggested by the low percentage of homozygous mutant offspring produced by heterozygous breeding pairs of Npc1nmf164 mice (R. Maue and R. Erickson, unpublished observation).

We used a broad scope, multi-faceted analysis to show that Npc1nmf164 mice display a similar, albeit slower, progression of neurodegenerative disease as found in the widely studied Npc1nih mutation: survival, overall weight loss (despite abnormal accumulation of lipids), abnormal reflex responses and loss of motor coordination (following Purkinje cell loss). There are, however, some intriguing differences. For years, it was thought that cholesterol did not accumulate in the brain in the Npc1nih model. Careful balance studies showed that storage in neurons is balanced by loss of myelin (53). No cholesterol increase, however, could be shown by biochemical measurement in dissected cerebral gray matter of autopsy material obtained from human patients (38). Although cholesterol accumulates in neuronal cell bodies in our new model (Figs 9 and 10), the marked loss of myelin seen in the Npc1nih mutant is not found with Npc1nmf164 (Fig. 12). On the other hand, the levels of the myelin component galactosylceramide appear to be reduced, albeit less than in the Npc1nih mouse (data not shown), thus more closely resembling the Npc2 mutant (26). The early inflammation noted in Npc1nih (33) is delayed (Fig. 8), as is the rate of Purkinje cell loss (Fig. 3, Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). Protein misfolding, as studied by immunostaining for BiP and CHOP, does not appear to play a major role in the neurodegeneration we observe with the D1005G mutation in the Npc1nmf164 mice. This contrasts to protein misfolding and instability in the relatively close I1061T mutation (23) that occurs in the same loop of the protein as the D1005G mutation. All of these aspects of Npc1nmf164 mice provide interesting avenues for future investigation and comparison.

In conclusion, although other existing null mutation mouse models may be representative of rapid and severe infantile onset forms of NPC disease (∼20% of cases), the hypomorphic Npc1nmf164 is a model of the juvenile disease. The location of the Npc1nmf164 missense mutation to a region where a high proportion of human mutations are found is combined with a late-onset, slower disease progression. The experimental advantages this offers (i.e. fertility of homozygous mutants) suggest that Npc1nmf164 mice are a valuable new model for understanding NPC disease and for developing effective treatments for the milder, late-onset forms that comprise the large majority of human cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal use and maintenance

Animal care conformed to standards established by the National Institutes of Health and was done in accordance with approved research protocols of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at Dartmouth, University of Arizona, and the Jackson Laboratory. Animals were exposed to a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum.

The following mouse strains were used in this study: Npc1m1N (designated here as Npc1nih, Npc1spm and Npc1nmf164 with Jackson stock numbers 3092, 2760, and 4817, respectively). Each of these strains is on a different genetic background (BALB/cNctr for nih, C57BLKS/J for spm and C57BL/6J for nmf164). Control mice were, therefore, littermates of mutant animals whenever possible, or wild-type controls strain-matched to the allele under study. Numbers and ages of animals are stated in the text for each experiment. The generation of the ENU-mutagenized strains and identification of recessive neurological mutations has been previously described (62,63).

Genotype determination

Genomic DNA was isolated from a 0.5 cm piece of tail tissue using a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). DNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at an OD of 260 nm. For genotyping, a Custom TaqMan® SNP genotyping assay was synthesized by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) and supplied as a 40× mix of the following primers and probes:

forward primer (5′-GGGTAAACAGAGGCCTCAGG-3′);

Wt probe (5′-VIC™ -TCCTTTCTG[A]TAACCC-3′);

mutant probe (5′-FAM™-CCTTTCTG[G]TAACCC-3′);

reverse primer (5′-CCCCTTTGCCGCACTTG-3′).

SNP genotyping was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system in a 10 µl of reaction volume containing: 6 ng genomic DNA, 1× TaqMan® Genotyping Master Mix and 1× SNP assay (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). DNA was amplified for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of (95°C for 15 s; 60°C for 1 min). Genotyping data were analyzed by ABI PRISM sequence detection software (SDS) version 2.1.

Genotyping by restriction enzyme analysis

We developed a restriction enzyme assay to genotype this single base change using BstEII which cuts with G, but not A, in the mutated sequence. Forward primer 5′-GGCCTCCAGGGGAAAGAATT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGGACCCTTCCGTACAAGC-3′ were used to generate a 176 bp PCR product. Cutting with BstEII leads to 128 and 48 bp fragments from the G allele.

Sequencing Npc1 transcripts

For identification of the nmf164 and spm mutations, mRNA was prepared from the brains of affected animals. This was reverse-transcribed (Superscript III; Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) using a mix of random and oligo-dT priming. The Npc1 coding sequence was amplified with the five overlapping primer combinations listed below. PCR products were gel-purified and sequenced using the same primers and aligned against equivalently prepared control samples using Sequencer. The nmf164 mutation was confirmed in genomic DNA by amplifying exon 20 of the Npc1 gene from genomic DNA, and the insertion in spm cDNA was confirmed as retained intron and the change in the exon 19 splice donor was also determined by amplifying and sequencing genomic DNA around exon 19.

cDNA sequencing primers

- 1F GTGCTCCGCGAGCCGAACTG

1R CCAGATCCTCCAGGGCATAG

- 2F CAGGACTGCTCCATCGTCTG

2R AGGACCGTGGAGCAAACTCG

- 3F CTGTACTGTGTACGGGCTCC

3R TTGTCCGTCGTCAGCGCCTC

- 4F CGGGAATGGCCGTCCTCATTG

4R AGGTCATGAAGTAAGTGGCC

- 5F GGACATGCTGCTTACGGTTC

5R TGACAGCGCAGCTGTCTTGC

Western blot analysis of NPC1 protein

Western blotting was performed as previously described (64). Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized and solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40 and a protease inhibitor mixture; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) on ice for 30 min. Protein concentrations in solubilized cell lysates were then determined by the Lowry method. After addition of (4×) SDS-loading buffer with 0.1 m dithiothreitol to 200 mg aliquots of the lysates, samples were kept on ice for at least 30 min and until sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis. A purified anti-peptide antibody raised against a human NPC1 protein sequence (the antibody generously gifted by Dr W. Garver) was diluted to 1000-fold in Tris-buffered solution, 0.3% Tween 20 buffer containing 1% skim milk and used for blotting. Signals in the western blots were quantified using NIH image (version 1.63). To normalize values, mean pixel intensities of the signals obtained with anti-NPC1 were divided by those obtained with the anti-β-actin antibody.

Reverse transcription coupled with qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels

The liver and brain tissue of mice were collected and stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) prior to RNA isolation using an RNAqueous Kit (Ambion). RNA concentration was determined at an OD of 260 nm. For cDNA synthesis, 50 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using a RETROscript First-Strand Synthesis Kit for RT-PCR (Ambion). To determine the relative abundance of the Npc1nmf164 mRNA, the cDNA in a 15 µl reaction volume containing 2.5 ng cDNA, 1× TaqMan® Universal Master Mix and 1× SNP assay (see primer sequences above) was amplified using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system and standard protocols: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The cycle threshold for detection (Ct) was determined using ABI PRISM software (SDS) version 2.1.

To analyze the relative abundance of the calbindin and SERCA 3A transcripts with commercially available primers [calbindin Mm00486645_m1,18S (20Hs99999901_s1) from Applied Biosystems], each mRNA sample was analyzed in triplicate, using 18S rRNA as an internal standard. For each mRNA assessed, a PCR master mix was prepared, containing final concentrations of: 1× TaqMan Universal Master Mix (containing AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase, AmpErase UNG, dNTPs with dUTP, Passive Reference 1 and optimized buffer components), 900 nm forward primer, 900 nm reverse primer, 250 nm probe in a total reaction volume of 25 µl. PCR for 18S rRNA was performed in a 25 µl reaction containing 1× TaqMan Universal Master Mix, 1× Eukaryotic 18S rRNA Endogenous Control (VIC/MGB Probe, Primer Limited; Applied Biosystems, Inc., Carlsbad, CA), to which 1 µl of cDNA was added. Thermocycling conditions included initial steps of 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C and 40 cycles of PCR at 95°C for 15 s to denature cDNA and 60°C for 1 min for primer/probe annealing and extension. Samples with reverse transcriptase omitted were used to control for genomic DNA contamination and samples with template omitted to control for any reagent contamination. The 2−ΔΔCT method (65,66) was used for determination of subunit mRNA levels.

Histological analyses

Tissue fixation

For analysis of liver, spleen and calbindin staining in cerebellum, tissues were fixed by overnight immersion in Bouin's fixative and embedded in paraffin before 4–5 mm thick sections were cut with a microtome (Leica Microsystems, Deerfield, IL, USA) and mounted on glass slides. For the confocal analysis of brain tissue and for the analysis of microglial activation, brains were fixed by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde and then embedded in either Tissue-Tek OCT medium (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) and frozen or in paraffin before 8 mm thick sections were cut with a cryostat microtome (Leica Microsystems) and mounted on glass slides. For ubiquitin staining, cerebellar samples were cut sagittally and fixed by immersion in acetic acid/methanol, paraffin-embedded and sectioned using a microtome for immunocytochemistry. For BiP and CHOP staining, samples were fixed in buffered 4% paraformaldehyde and sections were treated for antigen retrieval by boiling in 0.01 m citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 5 min.

Tissue labeling

Hematoxylin/eosin staining of liver and spleen tissue was performed by the Histology Service at the Jackson Laboratory, using standard protocols in a Leica Autostainer XL automated processor. For analysis of BiP, CHOP and ubiquitin, the following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-BiP (Grp78, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-CHOP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit anti-ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). For calbindin staining, cerebellar sections were deparaffinized and incubated with primary antibodies specific for calbindin (Swant) diluted 1:2000 in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS)/0.5% Triton/2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Signals were detected with the A-B-C System (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) using a biotinylated secondary anti-rabbit antibody followed by an horseradish peroxidase-conjugated avidin complex. Staining was visualized with diaminobenzidine (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA). For the confocal analysis of cholesterol in brain, care was taken to process tissue sections from mutant and wild-type animals in parallel. Sections were incubated in 15 μg/ml BC-Θ (courtesy Dr Y. Ohno-Iwashita, Tokyo, Japan) in PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum for 16 h at 4°C, rinsed and then incubated with streptavidin-Alexa 594 (1:150, Invitrogen) in PBS with 1% BSA for 1 h. After the sections were washed in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, they were then co-labeled by incubating them with NeuroTrace® 500/525 green fluorescent Nissl stain/RNA (1:150, Invitrogen) in PBS for 1 h. Sections were then rinsed in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, rinsed in PBS and coverslips affixed with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) mounting media.

For the analysis of microglial activation, brain sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by rehydration in graded incubations from 100% ethanol to dH2O. Antigen retrieval was performed with Borg decloaker (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA) in a pressure cooker for 45 min. Immunohistochemistry was carried out in PBS with 1% normal goat serum and 0.1% BSA. Microglia and astrocytes were labeled with rat anti-CD11b (1:100; Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA) and rabbit anti-GFAP (1:600; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), respectively, for 16 h at 4°C. After rinsing, sections were incubated for 1 h with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat or goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories). Slides were then rinsed, incubated for 15 min with 5% hydrogen peroxide in PBS, rinsed, stored in ABC solution (Vector Labs) for 90 min, rinsed and then labeled with 1 mg/ml diaminobenzidine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 10 mm imidazole and 0.03% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. Slides were then rinsed, dehydrated and coverslipped using Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) mounting medium.

Microscopy

For the confocal analysis of cholesterol in brain tissues, labeled sections were analyzed with a Leica TCS Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope System equipped with argon and argon/krypton lasers. Care was taken to ensure that images were collected within the linear range of intensity for the immunoreactivity in order to avoid saturation or underexposure of the field. Sections from mutant and wild-type mice were analyzed concurrently using the same thresholds and scanning parameters, and all images were captured on the same day to ensure comparable sensitivity and avoid daily variations in laser power that might affect staining intensity (67). For each antibody and mouse genotype, two to four tissue sections and two confocal images per section were collected and analyzed. For analysis of microglial activation, digital images of the tissues were collected using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a Qfire CCD camera and 40× objective lens. Fluorescence intensities for BiP and CHOP staining in Npc1nmf164 mutant and wild-type littermate controls were quantified using ImageJ software. Exposure-matched images were collected from slides processed in parallel (all mutant and control samples for a given genotype and a given age were stained together). Fluorescence intensities in the molecular layer (Purkinje cell dendrites) and Purkinje cell bodies (average of four cells per field) were determined and compared using a two-way Student's t-test. No significant differences with age or genotype were found (all P ≥ 0.3).

Evaluation of growth and lifespan

Npc1nih and Npc1nmf164 mice were monitored daily to determine their lifespan and were weighed weekly to monitor their growth, typically beginning at 3–4 weeks of age and continuing throughout the life of the animal up to 16–20 weeks.

Quantitative analyses of cholesterol esterification

Standard procedures and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (25) were used to obtain quantitative measurements of esterified and unesterified cholesterol in 15–115 mg of samples of liver tissue. Liver samples were extracted in 8 ml of chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v). The extracts were dried down under nitrogen, and the residue re-dissolved in 1 ml of MeOH. This solution was run over a pre-equilibrated Sep-Pak reversed-phase cartridge (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA), and the column then flushed five times with 5 ml of methanol to elute the free cholesterol. Cholesterol esters were then eluted by flushing the column with 2 ml of benzene. The cholesterol ester fraction was saponified in EtOH:Benzene:H2O (80:20:5) with 1 m KOH, and extracted with ethyl acetate. Free and esterified cholesterol fractions were dried down under nitrogen and trimethyl-silyl (TMS) derivatized as previously described (26). TMS cholesterol derivatives were quantified by selected ion monitoring using a Shimadzu QP 2010 GC-Mass Spec (Shimadzu Scientific, Columbia, MD, USA) with a 30-m long Zebron ZB1 wall coated open tubular column with a 0.25 mm inner diameter and 0.25 µm film thickness (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Deuterated cholesterol was used as an internal standard (Steraloids, Newport, RI, USA) and helium used as the gas carrier.

Lipid profiles and sphingolipid analyses

Liver and brain tissues were kept frozen at −25° or below until analysis. The procedures for lipid extraction, chromatographic separations and densitometric quantification were essentially similar to those used in previous studies (26,68). High-performance thin-layer silica gel 60 chromatography (HPTLC) plates were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Total lipids were extracted from a 20% tissue homogenate in water by 5 vol of chloroform:methanol 1:2 (v/v); after centrifugation, the tissue pellet was re-extracted similarly (26). The combined total extract was used for chromatographic examination of the main lipids after desalting by phase partition, using a chloroform–methanol–water 65:25:4 (by vol) developing system and the anisaldehyde spray reagent. For specific glycosphingolipid studies, part of the total lipid extract was desalted and separated into two fractions using 100 mg reverse-phase Bond Elut C18 (Varian) columns (69). Neutral glycosphingolipids were studied after saponification of the chloroform–methanol 1:2 (v/v) fraction (26). The acidic lipid fraction, eluted with methanol–water 12:1 (v/v), contained all the gangliosides and was used without further purification. Total sialic acid was measured by the Svennerholm's resorcinol method as described (68). A suitable aliquot of the extract (3 mg tissue equivalent) was spotted using a CAMAG Linomat 5 device on HPTLC plates developed with chloroform–methanol–0.2% CaCl2 55:45:10 (by vol) and sprayed with resorcinol–HCl reagent to visualize the sialic acid moiety of individual gangliosides. Densitometric quantification at 580 nm was performed using a CAMAG TLCII scanner equipped with the Cats Camag software. After normalization to the total sialic acid content, individual concentrations were calculated by taking into account the number of sialic acids for each ganglioside. Galactosylceramide was studied by densitometry at 505 nm of HPTLC plates developed in chloroform–methanol–acetic acid–water 75:25:2:1 (by vol) and indicated with an orcinol–sulfuric acid reagent using the same CAMAG devices. Free sphingoid bases (sphingosine and sphinganine) were studied by HPLC with fluorometric detection as previously described (40).

Magnetic resonance imaging

A 7 T horizontal bore Bruker Biospec instrument with a four-channel phased array surface coil (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA, USA) was used for all MRI experiments. Mice were anesthetized with a 1.5% concentration of isoflurane gas, monitored for breathing rate and temperature maintained at 37°C with a heated water system. An animal bed restraint system with bite and ear bars was used to prevent motion of the head during MRI experiments.

T2-weighted datasets were acquired with a radial fast spin echo sequence and imaging parameters: TR = 5000 ms, ETL = 8, echo spacing = 10 ms, 1024 radial lines acquired with 170 data points collected per line, 21 coronal 0.5 mm slices and a scan time of 10:40 (min:s). A reconstruction method using the oversampling of the central region of k-space in radial sampling (70) was used to create maps of T2. A region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was then carried in four areas of the brain known to contain large amounts of white matter, the CC, EC, IC, and Fimbria (FI). Regions were manually outlined on several image slices for each region with the aid of a mouse brain atlas (71), and average T2 values were calculated for each region. The resulting T2 data were analyzed using an analysis of variance method with a protected least significant difference test for post hoc analysis.

Motor behavior

In order to evaluate balance and motor coordination, mice were tested using three different tests: the inverted cage lid, the balance beam and the coat hanger (72,73). For the first, mice were placed on a wire cage lid before the cage lid was inverted, and the length of time the mouse could hang upside down (up to 60 s) was measured once a week. The balance beam consists of a 1 m rod with marked sections every 10 cm attached to two support columns 50 cm above a padded surface. Mice were tested on a weekly basis, and were given two trials every testing session. For each trial, animals were placed at the center of the beam and released. They were allowed 180 s to freely move on the beam. The time they stayed on the beam was recorded for both trials as well as the number of sections crossed (the higher the number, the better the performance). The coat hanger consists of a wire hanger suspended 35 cm above a padded surface in the beam apparatus. Initially, animals are permitted to grasp the wire with their forepaws and then released. Mice were allowed two trials of 30 s each. A rating system was used to assess their performance. The ratings are as follows: 0 = falls in <10 s; 1 = stays on hanger with one limb; 2 = stays on hanger with two limbs; 3 = stays on hanger with three limbs; 4 = stays on hanger with four limbs; 5 = reaches the end of the hanger and escapes onto beam.

A previously developed, video-based method of gait analysis (74) was also used to evaluate the gait of the NPC mice.

Acoustic startle

Auditory testing was carried out using the MED-ASR-PRO1/MED-ASR-FPS apparatus and software equipped with a single-chamber ENV-264Canimal holder (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA). Animals were placed in the acrylic test chamber mounted on a platform fitted with a piezoelectric force transducer attached to the underside of the platform. The platform was positioned inside a sound-attenuated test chamber that contained a high-frequency speaker for generating the auditory stimuli. Mice were acclimated in the chamber without stimuli for 8 min on two consecutive days prior to the testing. A 5 min acclimation period preceded test trials. The apparatus was cleaned with 70% ethanol between animals. All stimuli consisted of 50 ms white noise burst with a 1 ms rise/fall. Stimuli intensities and durations for behavioral tests were based on previously published studies defining criteria applicable to C57Bl/6 mice at ∼2 months of age (75,76). For the acoustic startle response, 60-pulse stimuli were presented with a 15 s inter-stimulus interval, using a random sequence of the following stimulus intensities: 80, 90, 100, 110, 120 dB. For habituation, 60 trials of a 110 dB stimulus were presented with an inter-stimulus interval of 10 s. For prepulse inhibition, half of the 20 startle stimuli (110 dB white noise for 50 ms) were presented alone and half were preceded by a prepulse (70 dB white noise for 20 ms) at a fixed interval (100 ms), with a 30 s inter-trial interval. The order of presentation of the individual trials was randomized. The acoustic startle response for each animal was calculated as the mean peak startle amplitude for a given intensity stimulus, normalized to the weight of the mouse. For the habituation data, the responses in five consecutive trials were averaged, and a best-fit trend line was fitted to the data points using Microsoft Excel. Percent prepulse inhibition was calculated as the percent decrease in the normalized startle amplitude following a prepulse, relative to the normalized amplitude of the startle alone trials. In all cases, results from individual animals were normalized to their body weight on the day of testing, and the average for a given wild-type group was compared with the corresponding mutant group using a paired t-test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers 5RO1 ED000343-5 (T.P.T.), R01HL036709 (T.Y.C.), R01DA014137 (L.P.H.), and UO1-NS41215 to the Neuroscience Mutagenesis Program at Jackson Laboratory], the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation (R.A.M., K.L.S. and R.W.B.), INSERM and Vaincre les Maladies Lysosomales (M.T.V.) and the Holsclaw Family Professorship of Human Genetics and Inherited Diseases (R.P.E.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr William S. Garver (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA) for the generous gift of antibody to Npc1/NPC1 peptide and Dr Y. Ohno-Iwashita (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, Tokyo, Japan) who, through the support of the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation, provided us with the BC-Θ reagent.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patterson M.C., Vanier M., Suzuki K., Morris J.A., Carstea E., Neufeld E.B., Blanchette Mackie J.E., Pentchev P.G. Niemann–Pick disease C: a lipid trafficking disorder. In: Scriver C.R., Beaudet A.L., Sly W.S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th edn. Vol. III. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 3611–3633. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanier M.T. Niemann–Pick disease type C. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-16. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pentchev P.G., Vanier M.T., Suzuki K., Patterson M.C. Niemann–Pick disease type C: a cellular cholesterol lipidosis. In: Scriver C.R., Stanbury J.B., Wyngaarden J.B., Frederickson D.S., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1995. pp. 2625–2639. [Google Scholar]