Abstract

Mutants of Salmonella enterica lacking apbC have nutritional and biochemical properties indicative of defects in iron-sulfur ([Fe-S]) cluster metabolism. An apbC mutant is unable to grow on tricarballylate as a carbon source. Based on the ability of ApbC to transfer an [Fe-S] cluster to an apoprotein, this defect was attributed to poor loading of the [Fe-S] cluster-containing TcuB enzyme. Consistent with these observations, a previous study showed that overexpression of iscU, which encodes an [Fe-S] cluster molecular scaffold, suppressed the tricarballylate growth defect of an apbC mutant (J. M. Boyd, J. A. Lewis, J. C. Escalante-Semerena, and D. M. Downs, J. Bacteriol. 190:4596–4602, 2008). In this study, tcuC mutations that suppress the growth defect of an apbC mutant by decreasing the intracellular concentration of tricarballylate are described. Collectively, the suppressor analyses support a model in which reduced TcuB activity prevents growth on tricarballylate by (i) decreasing catabolism and (ii) allowing levels of tricarballylate that are toxic to the cell to accumulate. The apbC tcuC mutant strains described here reveal that the balance of the metabolic network can be altered by the accumulation of deleterious metabolites.

INTRODUCTION

Iron and sulfur are essential to almost all bacteria, and cofactors containing these elements ([Fe-S] clusters) are nearly ubiquitous. Evolution has harnessed the flexible biochemical and biophysical properties of these cofactors for a variety of cellular functions, including enzymatic reactions, electron transfer, DNA metabolism, and environmental sensing (reviewed in references 8 and 27).

Three systems for [Fe-S] cluster biosynthesis have been described in bacteria. Work with Azotobacter vinelandii led to the discovery of the nif (nitrogen fixation) (55) and isc (iron-sulfur cluster) (54) [Fe-S] cluster biosynthetic operons. A third system, encoded by the suf (sulfur utilization factor) operon, was discovered in Escherichia coli (47). The genome of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium encodes both the iscSUA-hscAB-fdx-orf3 and sufABCDSE operons (36, 47).

Both bioinformatics and in vivo genetic approaches have identified several loci outside the isc, suf, and nif operons that impact [Fe-S] cluster metabolism. The apbC, rseC, and apbE loci were discovered in Salmonella enterica by using sensitive genetic screens that exploited phenotypes described for strains lacking isc operon functions (6, 7, 38, 44–46). ApbC is a 40-kDa cytoplasmic protein that can bind and rapidly transfer [Fe-S] clusters to a target protein (15) and hydrolyze ATP (16, 44). Both of these activities are necessary for in vivo function (16). ApbC is a representative member of an ancient family of [Fe-S] cluster biosynthetic proteins that evolved before the divergence of the Archaea and Eucarya (13). To our knowledge, all organisms that have sequenced genomes and are known to metabolize iron encode a copy of an apbC homologue. In contrast, the functions of the rseC and apbE gene products remain unknown.

The erpA, nfuA, cyaY, and ygfZ genes were identified in bacteria by using bioinformatic approaches, and subsequent physiological studies found that these gene products function in [Fe-S] metabolism (2, 4, 35, 37, 49). The NfuA and ErpA proteins show sequence similarity to the proposed [Fe-S] cluster-trafficking protein IscA, and like IscA, they have been shown to bind [Fe-S] clusters and transfer them to apoproteins (2, 4, 25, 35). Collectively, these studies have led to a model in which simple [Fe-S] clusters are synthesized using the Isc, Suf, or Nif system and are transferred to NfuA, ApbC, or A-type proteins that may traffic clusters to cellular targets (4, 15, 35). CyaY is hypothesized to be an Fe donor for [Fe-S] cluster biosynthesis (1, 49). The function of YgfZ remains unknown (51).

Thorough genetic analysis of loci involved in Fe and [Fe-S] cluster metabolism has been difficult because functional overlap between gene products complicates sensitive genetic screens. For instance, although the genomes of the model organisms S. enterica and E. coli contain both the isc and suf operons, either one of these operons is sufficient for cell viability (47). Furthermore, the genomes of these organisms encode the proposed [Fe-S] cluster scaffolding/trafficking proteins IscA, IscU, SufBCD, SufA, NfuA, ApbC, and ErpA. Biochemical and genetic studies have found that functional overlap exists between the IscU, NifU, and ApbC proteins, as well as between the A-type proteins ErpA, IscA, and SufA (14, 21, 48). With the exception of ErpA, NifU, and ApbC, genetic evidence to suggest preferential cellular targets for these [Fe-S] cluster scaffolding/trafficking proteins remains to be reported (26, 35).

The tricarballylate catabolic pathway in Salmonella enterica has shown promise as a genetic system with which to examine [Fe-S] cluster metabolism (14, 30). Importantly, the tricarballylate utilization genes tcuABC are carried in an operon, and a model for tricarballylate metabolism has been described (31, 33). In this model (Fig. 1A), TcuC transports tricarballylate across the inner membrane, where it is oxidized to cis-aconitate by the flavoprotein TcuA (31). During growth on tricarballylate, the reduced flavin of TcuA is recycled by TcuB, a membrane-bound protein that contains two [4Fe-4S] clusters and heme (32). Presumably, cis-aconitate is then hydrated to isocitrate by the [Fe-S] cluster-containing aconitase enzymes (AcnA, AcnB). The expression of the three-gene operon is under the control of TcuR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator (34). Induction of the tcuABC genes requires the presence of both TcuR and the coinducer tricarballylate.

Fig 1.

Tricarballylate catabolism in S. enterica. (A) Model for tricarballylate catabolism based on the work of Lewis et al. (31). TcuC protein transports tricarballylate into the cell, where it is oxidized to cis-aconitate by the flavoprotein TcuA. cis-Aconitate enters the TCA cycle through hydration to isocitrate, catalyzed by the aconitase enzymes (AcnA, AcnB). The reduced flavin of TcuA is recycled by passing the electrons to TcuB, which is thought to ultimately pass the electrons to the ubiquinone pool. ApbC is responsible for the insertion or repair of the two [4Fe-4S] clusters of TcuB. (B) A constraint at TcuB caused by the lack of ApbC has two consequences that can be solved by distinct suppressor mutations. First, decreased TcuAB activity prevents sufficient flux from tricarballylate from reaching the TCA cycle to allow growth. In this case, an increase in non-ApbC loading of clusters in TcuB increases TcuB function (caused by iscR mutations [14]). Second, tricarballylate accumulates, inhibiting isocitrate dehydrogenase and thus preventing growth (described in this study).

S. enterica strains lacking ApbC are unable to grow on tricarballylate as a sole carbon and energy source, and the TcuB protein has 100-fold-lower activity when overproduced in an apbC mutant than in a wild-type (wt) strain (14). Derepression of the isc operon or overexpression of iscU compensated for the lack of ApbC during growth on tricarballylate, contributing to a model in which ApbC was the primary cellular component responsible for the maintenance of the [Fe-S] clusters in TcuB (Fig. 1A) (14, 15).

This study continues efforts to gain insight into the function of ApbC in the context of the metabolic network of S. enterica. Collectively, our studies have culminated in a model in which a constraint at TcuB, caused by the lack of ApbC, has two consequences that can be solved by distinct mechanisms. First, decreased TcuAB activity prevents tricarballylate oxidation, resulting in insufficient carbon flux through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for growth. In this case, an increase in non-ApbC loading of clusters in TcuB (allowed by overexpression of the Fe-S cluster scaffold IscU [14]) increases TcuB function. Second, tricarballylate accumulates, inhibiting TCA-cycle enzymes and thus preventing growth (described in this study). Inhibition of tricarballylate transport decreased its accumulation and allowed time for the non-ApbC-mediated loading of clusters in TcuB. The tcuC mutant strains described here further our understanding of the consequences of the metabolic imbalance that occurs in the absence of ApbC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and chemicals.

All strains used in this study are derived from S. enterica LT2, and their genotypes are listed in Table 1. The NCE (no-carbon E salts) medium of Berkowitz et al. (9) was made with Milli-Q filtered water (MQH2O) and was supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 and trace minerals (3, 20, 50). Glucose, citrate, and tricarballylate were added to NCE medium at 11 mM, 11 mM, and 20 mM, respectively. Difco nutrient broth (NB) (8 g/liter) with NaCl (5 g/liter) or lysogenic broth (10, 11) was used as a rich medium. Difco BiTek agar was added (15 g/liter) for a solid medium. When present in the medium, supplements were provided at the following final concentrations: thiamine, 10 nM or 100 nM; adenine, 0.4 mM; nicotinic acid, 20 μM. When needed, antibiotics were added to the following concentrations in rich or minimal medium, respectively: tetracycline, 20 or 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 or 125 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 20 or 4 μg/ml; ampicillin, 50 or 15 μg/ml. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmidsa

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or vector (insert [source]) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Salmonella enterica | ||

| TR6585 | metE205 ara-9 | J. Roth |

| DM10310 | ara-9 (wild type) | |

| DM10300b | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet)c | 38 |

| DM10412 | ara-9 ybfM106::MudJ(kan) | 33 |

| DM11428 | ara-9 ybfM106::MudJ(kan) tcuB17 | 33 |

| DM10448 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC51 | |

| DM10449 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) | |

| DM10450 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC52 | |

| DM10452 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC54 | |

| DM11089 | ara-9 stcC::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC51 | |

| DM11090 | ara-9 stcC::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC54 | |

| DM11671 | ara-9 iscU::kan | |

| DM11046 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) iscU::kan | |

| JMB1732 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC51 acnB::kan | J. Escalente-Semerena |

| JMB1734 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC54 acnB::kan | |

| JMB1733 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC51 acnA::kan | |

| JMB1735 | ara-9 apbC55::Tn10d(tet) metT::Tn10d(cat) tcuC54 acnA::kan | |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| MG1655 | F− λ−ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 | 12 |

| DH5α/F′ | F′/endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR [80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] (E. coli) | New England Biolabs |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBAD30 | pBAD30 (none) | 24 |

| pTCUC5 | pBAD30 (tcuC [S. enterica]) | 32 |

| pSU19 | pSU19 (none) | 5 |

| pBAD24 | pBAD24 (none) | 24 |

| pJMB119 | pBAD30 (tcuC51 [S. enterica]) | This study |

| pJMB120 | pBAD30 (tcuC54 [S. enterica]) | This study |

| pJMB122 | pSU18 (tcuC [S. enterica]) | This study |

| pKD4 | pKD4 | 19 |

| pJMB127 | pSU18 (500 bp upstream of tcuA start codon) | This study |

| pJMB128 | pRS551 (500 bp upstream of tcuA start codon) | This study |

| pJMB276 | pBAD24 (acnA) | This study |

| pJMB277 | pBAD24 (acnB) | This study |

| pJMB278 | pBAD24 (icd) | This study |

| pRS551 | pRS551 | 43 |

All S. enterica strains constructed for this study were derivatives of a metE+ derivative of TR6583.

MudJ refers to the MudI1734 insertion element (18), and Tn10d(Tc) refers to the transposition-defective mini-Tn10 described by Way et al. (52).

The tet, cat, and kan genes encode resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and kanamycin, respectively.

Genetic methods. (i) Mutant isolation.

Nine independent cultures of DM10300 (apbC) were grown to full density in NB medium. One hundred microliters of each culture (∼107 CFU) was spread onto individual minimal tricarballylate thiamine plates. An average of 100 colonies arose spontaneously on each plate after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. One colony derived from each culture was saved.

(ii) Isolation of linked insertions.

The methods used for transduction and the purification of transductants have been described previously (22, 39, 41). Transposons [Tn10d(cat)] (23) genetically linked to the suppressor mutations were isolated by standard genetic techniques (28). In each case, mutant strains were reconstructed and were verified phenotypically prior to characterization. The relevant insertions were mapped by sequencing using a PCR-based protocol (University of Wisconsin Biotechnology DNA Sequence Facility) (17, 53).

Phenotypic analysis.

Nutritional requirements were assessed on solid medium and by quantification of growth in liquid medium using either 5-ml cultures in 25-ml shake tubes or 200-μl cultures in a 96-well plate. Protocols for each have been described elsewhere (7, 29). The starting A650 was routinely between 0.03 and 0.08, with a final A650 between 0.5 and 1.1. Each culture had at least three replicates. Growth on solid medium was scored after replica printing to the relevant medium and incubation at 37°C for 48 to 60 h.

β-Galactosidase assays.

One hundred microliters from overnight cultures grown in NB-kanamycin medium was used to inoculate 5 ml of NB-kanamycin medium with or without 20 mM tricarballylate (four replicates). Cultures were grown to an absorbance at 650 nm of 0.5 and were subsequently placed on ice. β-Galactosidase activity was assessed as described previously (34).

Molecular biology.

Restriction enzymes and DNA ligase were purchased from Promega, and Herculase DNA polymerase was purchased from Stratagene. Chromosomal DNA was purified using the Easy-DNA kit, purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The tcuC alleles were amplified from S. enterica by using genomic DNA as a template. The primers used were TcuC forward (5′-ATGGCACAACACACACCTGCAACA-3′) and TcuC reverse (5′-TCAGGCTTTATTTTCTGC-3′). The tcuC PCR products were gel purified and were ligated into pSU19 digested with SmaI, creating pJMB122 and pJMB121, respectively.

The acnA, acnB, and icd alleles were amplified from CCCCCATGGCGTCAACCCTACGAGAAGCCAGTAAGG) and 3′ primer acnA3pstI (CCCCTCAGGCCTGCCTGTTTACGGCAGGCCCG); for acnB, 5′ primer acnB5ncoI (CCCCCATGGTAGAAGAATACCGTAAGCACGTAGCTGA) and 3′ primer acnB3pstI (CCCCTGCAGCCCTTAAAATGTAAATTAAACCGCAGTCTGG); and for icd, 5′ primer icdA5NcoI (CCCCATATGGAAAGCAAAGTAGTTGTTCCGGTGGAAGG) and 3′ primer icdA3SalI (CCCGTCGACCGTTATTACATATTCGCGATAATCGCGTCACC). The PCR products were digested, gel purified, and ligated into pBAD24 (24) that had been digested with NcoI and SalI (isd) or NcoI and PstI (acnA or acnB).

The tcup-lacZ transcriptional fusion was created by amplifying the 500 bp upstream of the tcuA start codon using genomic DNA and tcuA promoter primers with either a 5′ EcoRI site (5′-AAAGAATTCTCCTGATAACCCGATCACACCT-3′) or a 3′ BamHI site (5′-CCCGGATCCCTTATACTCCCGTACCATTT-3′). The PCR product was gel purified and was blunt-end cloned into the SmaI site of pSU18, creating pJMB127. Plasmids pJMB127 and pRS551 were cut with EcoRI and BamHI; the fragments were separated using agarose gel electrophoresis; and the desired fragments were gel purified. The 500-bp tcu promoter fragment cut from pJMB127 was gel purified and was ligated into cut pRS551, creating pJMB128.

The iscU gene was disrupted with a kanamycin insert by the methods of Datsenko and Wanner using the following primers (19): DiscUfor (5′-TGTGGATCTGAACAGCATCGAATGGGCACATCATTAATCGGTATCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′) and DiscUrev (5′-GGAAGGTATTAACTCGCGCTGCTGCACTGTCGCTAAGTGTAATCGACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′).

The acnA::kan and acnB::kan alleles were verified using the following primers: acnAVeri5 (CACCGCAGCAGCGGGCATTTATTGATGC), acnAveri3 (GCGGAAGAAGGACGCGGTATTCTGATTTACC), acnBveri3 (GGCCCACCACAAAATACCAATACATAC), and acnBveri5 (GCCGCCGACGGGGTGCAGTTT).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mutations in tcuC suppress the growth defect of an apbC mutant on tricarballylate.

An S. enterica apbC mutant strain does not grow on tricarballylate as a carbon and energy source but is proficient for growth on glucose and other carbon sources (e.g., succinate, gluconate) (14). Five of nine independent spontaneous mutations that allowed strain DM10300 (apbC) to grow on a solid medium with 20 mM tricarballylate mapped to the iscR gene and have been described previously (14). Genetic analysis determined that a Tn10d(cat) insertion in metT was ∼40% cotransducible by phage P22 with the remaining four suppressor mutations, placing them near the tcu operon. Sequence analysis determined that each of the four mutations was a single base change in the tcuC gene, encoding the tricarballylate transporter (33). The mutations resulted in variant TcuC proteins with G137S (tcuC51), C198S (isolated twice) (tcuC54), and W319R (tcuC52).

In a medium with tricarballylate as the sole carbon and energy source, strain DM10310 (wild type) had a doubling time of 1.4 ± ≤0.05 h, while strain DM10300 (apbC) had no detectable growth. Strains DM10448 (apbC tcuC51) and DM10452 (apbC tcuC54) had doubling times of 3.0 ± ≤0.05 and 4.1 ± ≤0.05 h, respectively, on tricarballylate. In addition to the increased doubling times of the suppressed strains, there was a significant lag prior to the initiation of growth (Fig. 2). Suppression of the growth defect by tcuC52 was weak, and this allele was not characterized further.

Fig 2.

tcuC alleles allow the growth of apbC mutants after a lag. Shown is the growth of strains DM10310 (wild type) (●), DM10300 (apbC) (○), DM10452 (apbC tcuC51) (■), and DM10448 (apbC tcuC54) (▴) with 20 mM tricarballylate as the sole carbon and energy source at 37°C in NCE medium supplemented with 100 nM thiamine. Outgrowth after reinoculation had the same lag times as those shown here.

The tcuC alleles restored the growth of an apbC mutant on tricarballylate after a lag time of 15 to 30 h depending on the allele (Fig. 2). Upon reinoculation (e.g., outgrowth in fresh medium), the cultures displayed the same delay, demonstrating that the lag was an inherent property of the tcuC derivatives. We hypothesized that the lag reflected the time needed for the [Fe-S] clusters of TcuB to be loaded by an alternative (ApbC-independent) mechanism, resulting in a TcuB population capable of tricarballylate turnover.

Suppressing tcuC alleles are recessive and encode variants that decrease tricarballylate transport.

Plasmid pTCUC5 (carrying functional TcuC) was transformed into the wild-type strain (DM10310) and apbC tcuC double mutant strains (DM10448, DM10452). The mutant strains lost the ability to grow on tricarballylate when plasmid pTCUC5 was present, but not with the empty vector (data not shown). The wild-type strain grew on tricarballylate with both plasmids, and all strains grew on glucose medium. These data supported the conclusion that the suppressor alleles of tcuC were recessive.

The introduction of tcuC54 into a wild-type strain significantly reduced the growth of the strain in tricarballylate medium (Fig. 3). The doubling times for strains DM10310 (wt) and DM11090 (tcuC54) were 2.3 ± ≤0.05 and 2.4 ± ≤0.05 h, respectively, in 10 mM tricarballylate and 1.7 ± ≤0.05 and 3.0 ± 0.1 h, respectively, in 20 mM tricarballylate. DM11098 (tcuC51) showed the same general growth trends as DM11090 (tcu54) (data not shown). Under each condition, the tcuC mutant strains reached a slightly lower final density than the wild-type strain, suggesting that the TcuC variants might have a reduced affinity for tricarballylate in addition to a reduced velocity.

Fig 3.

Mutations in tcuC reduce growth on tricarballylate. Shown is the growth of strains DM10310 (wild type) (triangles) and DM11090 (tcuC54) (squares) with 10 mM (filled symbols) or 20 mM (open symbols) tricarballylate as the sole carbon and energy source at 37°C in NCE medium supplemented with 100 nM thiamine.

The E. coli MG1655 genome does not encode the tcu operon or a citrate transporter, rendering the strain unable to grow on citrate as a sole carbon source. Heterologous expression of tcuC in MG1655 results in sufficient transport of citrate to allow growth (33, 42). Thus, the growth of E. coli strain MG1655 on citrate provided a means of measuring the transport activities of TcuC variants. Derivatives of MG1655 carrying plasmid pJMB122 (tcuC), pJMB119 (tcuC51), or pJMB120 (tcuC54) were generated, and growth on citrate was measured. The MG1655 strain carrying the empty vector had no detectable growth on citrate (11 mM). As reported previously, the MG1655 strain carrying pJMB122 (tcuC) grew with citrate (doubling time, 2.0 ± ≤0.05 h; final A650, 0.5 ± ≤0.05). Plasmids pJMB119 (tcuC51) and pJMB120 (tcuC54) allowed growth on citrate, although with slightly greater doubling times (2.3 ± ≤0.05 and 2.6 ± ≤0.05 h, respectively) and lower final yields (A650, 0.2 ± ≤0.05 for both strains) than those of the strain carrying pJMB122 (tcuC). All strains grew similarly on glucose medium (data not shown). In total, the data presented above supported the conclusion that the suppressing alleles of tcuC encoded variant proteins whose transport function was compromised.

Isolation of tcuC mutations uncovers the inhibitory effect of tricarballylate in vivo.

Previous results suggested that ApbC was involved in the maturation and/or repair of the [Fe-S] clusters in TcuB. These results led to the model (Fig. 1) that compromised TcuB activity prevented the oxidation of tricarballylate to cis-aconitate, which led to the inability of an apbC mutant to grow on tricarballylate (15, 30). The isolation of tcuC mutants with mutations that suppressed the growth defect called for a reevaluation of this simple model. We hypothesized that the tcuC alleles suppressed the growth defect of an apbC mutant by reducing the intracellular accumulation of tricarballylate caused by compromised TcuB activity.

In this scenario, the inability of apbC mutants to grow on tricarballylate would be caused by the accumulation of tricarballylate, inhibiting TCA-cycle enzymes, before TcuB could be sufficiently loaded with [Fe-S] clusters by the non-ApbC mechanism. By compromising TcuC, tricarballylate accumulation would be restricted, and the cells would be able to initiate outgrowth when the enzymes became available. This scenario depends on the hypothesis that the accumulation of tricarballylate is inhibitory.

Strains with mutant tcuC alleles have lower intracellular tricarballylate levels.

Transcription of the tcu operon provides a qualitative measure of tricarballylate levels in the cell, since tricarballylate is a necessary coactivator for TcuR, the activator of the tcu operon (34). The 500 bp upstream of the tcuA start codon was cloned into a promotorless lacZ+ fusion vector (pRS551) (43), generating pJMB128. Strains containing pJMB128 were grown to mid-log phase in NB medium with or without tricarballylate and were assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Table 2). With all strains, tricarballylate was required for significant β-galactosidase activity. An apbC mutant (DM10449) had ∼1.3-fold higher β-galactosidase activity than the wild-type strain (DM10310). The presence of the tcuC51 (DM11089) or tcuC54 (DM11090) allele resulted in an ∼2.2-fold reduction in β-galactosidase activity, suggesting that less tricarballylate was present in the cell. The apbC tcuC double mutants (DM10448, DM10452) had ∼1.3-fold higher β-galactosidase activity than the tcuC single mutants (DM11089, DM11090) and ∼2.6-fold lower activity than the apbC single mutant (DM10449). These data are consistent with a model in which tricarballylate accumulates in an apbC mutant and the variant TcuC proteins reduce this accumulation.

Table 2.

Expression of the tcu operon is increased in an apbC mutant and decreased in tcuC mutantsa

| Strain name | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activityb (Miller units) in NB medium: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without tricarballylate | With tricarballylate | ||

| DM10310 | Wild type | 9 ± 1 | 265 ± 10 |

| DM10449 | apbC | 8 ± 1 | 333 ± 4 |

| DM10448 | apbC tcuC51 | 8 ± 1 | 125 ± 4 |

| DM10452 | apbC tcuC54 | 9 ± 1 | 132 ± 7 |

| DM11089 | tcuC51 | 8 ± 1 | 90 ± 4 |

| DM11090 | tcuC54 | 9 ± 1 | 100 ± 3 |

Cultures were grown in nutrient broth medium with kanamycin in the presence or absence of 20 mM tricarballylate to an absorbance at 650 nm of 0.5.

Assessed as described previously (34).

Tricarballylate accumulation is toxic in vivo.

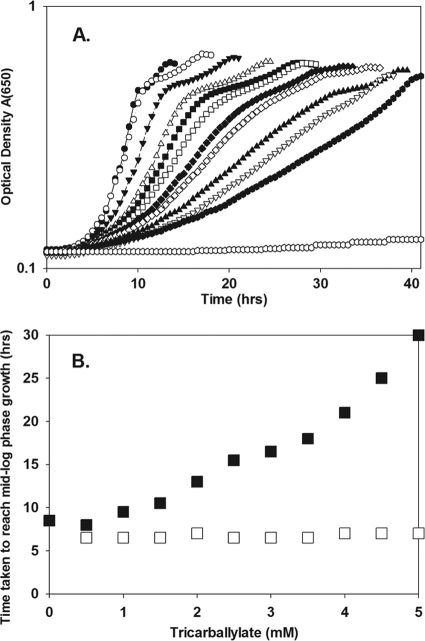

Cells were grown with citrate, which does not require TcuABC function, and were challenged with tricarballylate. This experiment uncoupled tricarballylate inhibition from tricarballylate utilization. The mutant allele tcuB17 encodes a nonfunctional TcuB protein and completely eliminates growth on tricarballylate. Further, this allele is nonpolar and thus does not affect the level of tcuC (33). Strains DM10310 (wild type) and DM11428 (tcuB17) were grown with 11 mM citrate in the absence or presence (at 10 mM) of tricarballylate. Strain DM11428 (tcuB17) could not grow on citrate if tricarballylate was included in the medium at a concentration above 6 mM (Fig. 4A), while the growth of the wild-type strain was unaffected by concentrations of tricarballylate up to 50 mM (data not shown). At concentrations of tricarballylate below 6 mM, the inhibition of growth was quantified by the average time a culture took to reach mid-log phase. The data in Fig. 4 showed that strain DM11428 (tcuB17) was sensitive to tricarballylate when growing with citrate, whereas strain DM10310 (wild type) was not. These results were consistent with an inhibitory effect of tricarballylate, which would accumulate in the tcuB mutant and not the wild-type strain. Strain DM11428 (tcuB17) did not have a growth defect when grown with glucose, succinate, malate, fumarate, or gluconate in the presence of 10 mM tricarballylate (data not shown). Together these data suggested that the target of the accumulated tricarballylate was one or more enzymes of the TCA cycle. The in vivo analyses described below addressed this general hypothesis.

Fig 4.

A tcuB mutant strain is sensitive to tricarballylate when growing with citrate. (A) Strain DM11428 (tcuB17) was grown with citrate (11 mM) with increasing concentrations of tricarballylate in the growth medium. The data presented are from a representative experiment showing growth in the absence of tricarballylate (filled circles) and in the presence of 0.5 mM (open circles), 1 mM (filled inverted triangles), 1.5 mM (open triangles), 2 mM (filled squares), 2.5 mM (open squares), 3 mM (filled diamonds), 3.5 mM (open diamonds), 4 mM (filled triangles), 4.5 mM (open inverted triangles), 5 mM (filled hexagons), and 6 mM (open hexagons) tricarballylate. (B) Plot of the time that strains DM10412 (wt) (□) and DM11428 (tcuB17) (■) took to reach mid-log phase when grown on citrate (11 mM) versus the concentration of tricarballylate present in the growth medium. Growth was monitored at 37°C in NCE medium supplemented with 100 nM thiamine and 20 μM nicotinic acid.

When strain DM10300 (apbC) was grown in citrate (11 mM), the time required to reach log phase was proportional to the concentration of tricarballylate, although this strain tolerated a much higher concentration of tricarballylate than strain DM11428 (tcuB17). These data were expected, since TcuB is only partially inactive in an apbC mutant (14). Consistent with the hypothesis described above, the presence of either the tcuC51 or the tcuC54 allele relieved the growth defect of an apbC mutant on citrate with tricarballylate (Fig. 5). The growth of strains carrying only the tcuC alleles on citrate was unaffected by tricarballylate at concentrations as high as 30 mM (data not shown).

Fig 5.

An apbC mutant is sensitive to tricarballylate when grown on citrate, and the growth defect is relieved by the presence of a mutant tcuC allele. Shown is a plot of the time required for strains DM10300 (apbC) ○), DM10448 (apbC tcuC51) (□), and DM10452 (apbC tcuC54) (▴) to reach the mid-log phase of growth when growing on citrate versus the concentration of tricarballylate added to the growth medium. Growth was monitored in NCE medium with 11 mM citrate supplemented with 100 nM thiamine, 20 μM nicotinic acid, and 0 to 30 mM tricarballylate.

The target(s) of the inhibitory effect of tricarballylate was investigated by genetic means. A series of results were most consistent with tricarballylate compromising growth by inhibiting the enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase (Icd). Overexpression of aconitase alleles (acnA or acnB) did not alter the growth phenotypes of apbC mutant strains on tricarballylate. Furthermore, elimination of either AcnA or AcnB in the apbC tcuC double mutant strains had no effect on the growth suppression allowed by the tcuC alleles. In contrast, overexpression of Icd significantly reduced the lag displayed by the apbC mutant strains (data not shown). Although tricarballylate has been shown to inhibit aconitase in vitro, the data presented above suggest that tricarballylate inhibition of Icd is more relevant in generating the in vivo growth phenotypes (40). Icd is required for growth on malate and succinate, yet the apbC mutant strains are not sensitive to tricarballylate on these carbon sources. Since malate and succinate derepress the TCA cycle, it is likely that despite being inhibited, Icd can provide enough ketoglutarate for growth under these conditions. This interpretation is consistent with the ability of overexpressed Icd to restore growth in the presence of tricarballylate (described above).

Mutations in iscU exacerbate sensitivity to tricarballylate.

Overexpression of iscU suppressed the tricarballylate growth defect of an apbC mutant, yet a strain lacking iscU did not have a growth defect on tricarballylate (14). These data led to the hypothesis that IscU could partially compensate for ApbC in the maturation of TcuB. In this scenario, the double mutant would have a more severe phenotype than either parental single mutant. Strains DM10300 (apbC), DM11671 (iscU), and DM11046 (apbC iscU) were grown with 11 mM citrate in the presence of 0 to 30 mM tricarballylate. The presence of tricarballylate in the growth medium did not affect the time that it took the iscU mutant (DM11671) to reach mid-log-phase growth, but both strains DM10300 (apbC) and DM11221 (iscU apbC) took longer to reach log phase when tricarballylate was present (Fig. 6). The iscU apbC double mutant was significantly more sensitive to tricarballylate than the apbC single mutant, consistent with the hypothesis that the growth of apbC mutants is allowed by IscU-dependent maturation of the [Fe-S] clusters in TcuB. Consistent with this interpretation was the finding that the tcuC mutations failed to restore growth on tricarballylate as a sole carbon source to the apbC iscU double mutant (data not shown).

Fig 6.

The presence of a mutation in iscU exacerbates the growth defect of an apbC mutant. Strains DM10300 (apbC) (○), DM11671 (iscU) (▴), and DM11221 (apbC iscU) (▵) were grown with citrate in the presence of 0 to 30 mM tricarballylate. The time that it took these strains to reach the mid-log phase of growth was plotted against the concentration of tricarballylate present in the growth medium. Growth was monitored in NCE medium with 11 mM citrate supplemented with 100 nM thiamine and 20 μM nicotinic acid.

Summary.

Collectively, our studies have led to a model for the inability of apbC mutants to grow with tricarballylate as a sole carbon source (Fig. 1). In the absence of ApbC, TcuB protein is defective, which leads to the accumulation of tricarballylate in the cytoplasm. Our data suggest that tricarballylate is toxic to cells because it inhibits citric acid cycle enzymes, which are required for tricarballylate metabolism. Our model suggests that increasing the amount of active [4Fe-4S] cluster-loaded TcuB protein through overexpression of IscU will reduce the tricarballylate concentration. Here we found that the intracellular tricarballylate concentration could be lowered by decreasing the activity of the tricarballylate transporter TcuC. We hypothesize that lowering the intracellular tricarballylate concentration by either means is sufficient to relieve the tricarballylate-mediated inhibition of isocitrate dehydrogenase and to allow increased carbon flux through the citric acid cycle to yield cell growth.

The finding that the growth defects of a strain with a null apbC allele were similar to, but not as severe as, those of a strain with a null tcuB allele (i.e., lack of growth on tricarballylate, sensitivity to tricarballylate) suggested that a fraction of TcuB protein remained active in a strain with an apbC mutation. The residual TcuB activity may reflect the permissiveness of alternative cellular components that have the ability to insert or repair the [Fe-S] clusters in TcuB in the absence of ApbC protein. Consistent with this interpretation, mutation of any of a number of genes involved in Fe or [Fe-S] cluster metabolism (apbE, rseC, cyaY, gshA, iscU, iscA, fdx, hscAB, etc.) abolished the growth of the apbC tcuC strain on tricarballylate medium (data not shown). These studies emphasize the need for balance in the metabolic network and illustrate that accumulation and/or depletion of key metabolites can impact cellular function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by competitive grant GM47296 (to D.M.D.) and a Kirschstein postdoctoral training grant (GM079938-02 [to J.M.B.]) from the NIH. The Gerhardt Scholarship from the Department of Bacteriology supported W.P.T.

The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Adinolfi S, et al. 2009. Bacterial frataxin CyaY is the gatekeeper of iron-sulfur cluster formation catalyzed by IscS. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:390–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angelini S, et al. 2008. NfuA, a new factor required for maturing Fe/S proteins in Escherichia coli under oxidative stress and iron starvation conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 283:14084–14091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balch WE, Wolfe RS. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32:781–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandyopadhyay S, et al. 2008. A proposed role for the Azotobacter vinelandii NfuA protein as an intermediate iron-sulfur cluster carrier. J. Biol. Chem. 283:14092–14099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. BartolomÉ B, Jubete Y, Martinez E, de la Cruz F. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beck BJ, Connolly LE, De Las Penas A, Downs DM. 1997. Evidence that rseC, a gene in the rpoE cluster, has a role in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 179:6504–6508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck BJ, Downs DM. 1998. The apbE gene encodes a lipoprotein involved in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 180:885–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beinert H, Holm RH, Munck E. 1997. Iron-sulfur clusters: nature's modular, multipurpose structures. Science 277:653–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berkowitz D, Hushon JM, Whitfield HJ, Roth J, Ames BN. 1968. Procedure for identifying nonsense mutations. J. Bacteriol. 96:215–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertani G. 2004. Lysogeny at mid-twentieth century: P1, P2, and other experimental systems. J. Bacteriol. 186:595–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bertani G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62:293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blattner FR, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boyd JM, Drevland RM, Downs DM, Graham DE. 2009. Archaeal ApbC/Nbp35 homologs function as iron-sulfur cluster carrier proteins. J. Bacteriol. 191:1490–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boyd JM, Lewis JA, Escalante-Semerena JC, Downs DM. 2008. Salmonella enterica requires ApbC function for growth on tricarballylate: evidence of functional redundancy between ApbC and IscU. J. Bacteriol. 190:4596–4602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd JM, Pierik AJ, Netz DJ, Lill R, Downs DM. 2008. Bacterial ApbC can bind and effectively transfer iron-sulfur clusters. Biochemistry 47:8195–8202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boyd JM, Sondelski JL, Downs DM. 2009. Bacterial ApbC protein has two biochemical activities that are required for in vivo function. J. Biol. Chem. 284:110–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caetano-Anolles G. 1993. Amplifying DNA with arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. PCR Methods Appl. 3:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Castilho BA, Olfson P, Casadaban MJ. 1984. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-mu bacteriophage transposons. J. Bacteriol. 158:488–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis RW, Botstein D, Roth JR, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dos Santos PC, Johnson DC, Ragle BE, Unciuleac MC, Dean DR. 2007. Controlled expression of nif and isc iron-sulfur protein maturation components reveals target specificity and limited functional replacement between the two systems. J. Bacteriol. 189:2854–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Downs DM, Petersen L. 1994. apbA, a new genetic locus involved in thiamine biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:4858–4864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elliott T, Roth JR. 1988. Characterization of Tn10d-Cam: a transposition-defective Tn10 specifying chloramphenicol resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 213:332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jin Z, et al. 2008. Biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters in photosystem I: holo-NfuA from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 rapidly and efficiently transfers [4Fe-4S] clusters to apo-PsaC in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 283:28426–28435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK. 2005. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:247–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kiley PJ, Beinert H. 2003. The role of Fe-S proteins in sensing and regulation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleckner N, Roth J, Botstein D. 1977. Genetic engineering in vivo using translocatable drug-resistance elements. New methods in bacterial genetics. J. Mol. Biol. 116:125–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koenigsknecht MJ, Fenlon LA, Downs DM. 2010. Variants of phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase (PrsA) alter cellular pools of ribose 5-phosphate and influence thiamine synthesis in S. enterica. Microbiology 156:950–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis JA, Boyd JM, Downs DM, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2009. Involvement of the Cra global regulatory protein in the expression of the iscRSUA operon, revealed during studies of tricarballylate catabolism in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 191:2069–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lewis JA, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2006. The FAD-dependent tricarballylate dehydrogenase (TcuA) enzyme of Salmonella enterica converts tricarballylate into cis-aconitate. J. Bacteriol. 188:5479–5486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lewis JA, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2007. Tricarballylate catabolism in Salmonella enterica. The TcuB protein uses 4Fe-4S clusters and heme to transfer electrons from FADH2 in the tricarballylate dehydrogenase (TcuA) enzyme to electron acceptors in the cell membrane. Biochemistry 46:9107–9115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lewis JA, Horswill AR, Schwem BE, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2004. The tricarballylate utilization (tcuRABC) genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. J. Bacteriol. 186:1629–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewis JA, Stamper LW, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2009. Regulation of expression of the tricarballylate utilization operon (tcuABC) of Salmonella enterica. Res. Microbiol. 160:179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loiseau L, et al. 2007. ErpA, an iron sulfur (Fe S) protein of the A-type essential for respiratory metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:13626–13631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McClelland M, et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ote T, et al. 2006. Involvement of the Escherichia coli folate-binding protein YgfZ in RNA modification and regulation of chromosomal replication initiation. Mol. Microbiol. 59:265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Petersen L, Downs DM. 1996. Mutations in apbC (mrp) prevent function of the alternative pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:5676–5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roberts GP. 1978. Isolation and characterization of informational suppressors in Salmonella typhimurium. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Berkeley, CA [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schloss JV, Emptage MH, Cleland WW. 1984. pH profiles and isotope effects for aconitases from Saccharomycopsis lipolytica, beef heart, and beef liver. α-methyl-cis-aconitate and threo-Ds-α-methylisocitrate as substrates. Biochemistry 23:4572–4580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schmieger H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 119:75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shimamoto T, Negishi K, Tsuda M, Tsuchiya T. 1996. Mutational analysis of the CitA citrate transporter from Salmonella typhimurium: altered substrate specificity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 226:481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Simons RW, Houman F, Klechner N. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for proteins and operon fusions. Gene 53:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Skovran E, Downs DM. 2003. Lack of the ApbC or ApbE protein results in a defect in Fe-S cluster metabolism in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 185:98–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Skovran E, Downs DM. 2000. Metabolic defects caused by mutations in the isc gene cluster in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: implications for thiamine synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 182:3896–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Skovran E, Lauhon CT, Downs DM. 2004. Lack of YggX results in chronic oxidative stress and uncovers subtle defects in Fe-S cluster metabolism in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 186:7626–7634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takahashi Y, Tokumoto U. 2002. A third bacterial system for the assembly of iron-sulfur clusters with homologs in archaea and plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 277:28380–28383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vinella D, Brochier-Armanet C, Loiseau L, Talla E, Barras F. 2009. Iron-sulfur (Fe/S) protein biogenesis: phylogenomic and genetic studies of A-type carriers. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vivas E, Skovran E, Downs DM. 2006. Salmonella enterica strains lacking the frataxin homolog CyaY show defects in Fe-S cluster metabolism in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 188:1175–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vogel HJ, Bonner DM. 1956. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Waller JC, et al. 2010. A role for tetrahydrofolates in the metabolism of iron-sulfur clusters in all domains of life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:10412–10417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Way JC, Davis MA, Morisato D, Roberts DE, Kleckner N. 1984. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene 32:369–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Webb E, Claas K, Downs D. 1998. thiBPQ encodes an ABC transporter required for transport of thiamine and thiamine pyrophosphate in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8946–8950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zheng L, Cash VL, Flint DH, Dean DR. 1998. Assembly of iron-sulfur clusters. Identification of an iscSUA-hscBA-fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13264–13272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zheng L, White RH, Cash VL, Jack RF, Dean DR. 1993. Cysteine desulfurase activity indicates a role for NIFS in metallocluster biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:2754–2758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]