Abstract

We report a case of chest wall abscess caused by Mycobacterium bovis BCG that arose as a complication 1 year after intravesical BCG instillation. We identified M. bovis BCG Tokyo 172 in the abscess by PCR-based typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and analysis of variable number of tandem repeats data.

CASE REPORT

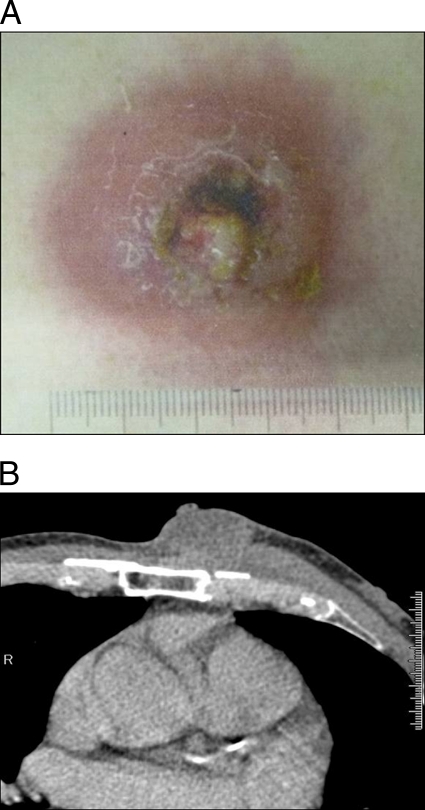

A 69-year-old man was referred to our hospital with an anterior chest wall abscess in April 2010. In pus from the abscess, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTC) was detected by PCR, but no acid-fast bacilli were observed by Ziehl-Neelsen staining (Fig. 1A). He had noted a palpable mass on the anterior chest wall and pain at the same site in February 2010. There was no history of fever, chills, malaise, night sweats, cough, or sputum. He had not consumed unpasteurized dairy products and had not been in close contact with cattle. He had received Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine as a child but not as an adult. There was no history of tuberculosis infection. However, he had a history of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and had received intravesical BCG (Connaught strain) instillation from August to November 2007. After recurrence of the bladder cancer, transurethral resection had been performed in August 2008. Further intravesical BCG (Tokyo 172 strain) instillation had been done for carcinoma in situ of the bladder from February to April 2009.

Fig 1.

Macroscopic (A) and computed tomography (B) findings on the chest wall abscess. The scale is graduated in millimeters.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest revealed a subcutaneous abscess with slight rim enhancement on the left anterior chest wall. There were no abnormalities of the lungs and mediastinum (Fig. 1B). A whole-blood gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release assay (IGRA) was performed using the QuantiFERON-TB gold in-tube (QFT-3G) test (Cellestis, Victoria, Australia), which includes M. tuberculosis-related antigens ESAT-6, CFP-10, and TB7.7, but the result was negative. Further investigation was conducted to identify the source of infection. After aspiration of the chest wall abscess, pus was inoculated into Ogawa medium for mycobacterial culture. We obtained a colony of MTC that was named strain M9. MICs were measured with a microdilution antimycobacterial susceptibility test (BrothMIC MTB; Kyokuto Pharmaceutical Industrial Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). It is well known that all BCG vaccine strains are naturally resistant to pyrazinamide, and the Connaught strain shows low-level isoniazid resistance (12). The eight antimycobacterial agents tested were isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, kanamycin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. It was found that strain M9 was susceptible to all eight antimicrobial agents.

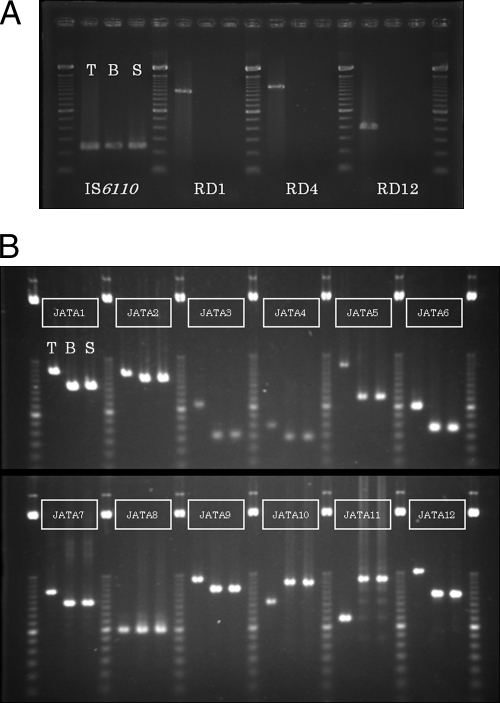

To identify the origin of the bacteria in the abscess, DNA was extracted from strain M9 with a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, CA). PCR deletion analysis was done to make use of MTC chromosomal region-of-difference deletion loci. Three primer pairs (amplifying the Rv3877/8:RD1, Rv1510:RD4, and Rv3120:RD12 loci) and an IS6110 (MTC containing)-specific primer pair were selected and run in separate reactions (5). In MTC members, both of the elements RD4 and RD12 do not exist in M. bovis and M. bovis BCG. The RD1 element is present in M. bovis but is absent in M. bovis BCG. In PCR fragments of strain M9, the RD1, RD4, and RD12 loci were not detected, but IS6110 was found, as in M. bovis BCG (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that strain M9 was M. bovis BCG.

Fig 2.

Results of PCR-based MTC typing (A) and VNTR typing with the 12-locus JATA primer set (B). T, M. tuberculosis strain isolated from another clinical case; B, BCG Tokyo 172 strain; S, M9 strain.

Variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) typing was also done to compare the allelic profile of strain M9 with that of M. bovis BCG. Tandem repeats are about 40- to 100-bp DNA elements that are often dispersed in intergenic regions of the MTC genome. These structures evolve slowly in mycobacterial populations (14). VNTR analysis was performed with 12 primer pairs from the Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association (JATA) that amplified the following loci: VNTRs 0424, 0960, 1955, 2074, 2163b, 2372, 2996, 3155, 3192, 3336, 4052, and 4156 (JATA1 to JATA12) (8, 10). It was found that all 12 tandem repeats from strain M9 (0,2,0,3,3,1,5,5,3,10,5,1) were identical to those of M. bovis BCG (Tokyo 172) (Fig. 2B). Strain M9, possessing allele 10 at the JATA10 (VNTR3336) locus, differed from the Connaught strain, having allele 11 (13). Thus, the final diagnosis was a chest wall abscess due to M. bovis BCG (Tokyo 172) that arose as a complication at 1 year after intravesical instillation of BCG.

The patient was treated with a four-drug regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, as well as surgical intervention. Although M. bovis BCG was found to be intrinsically resistant to pyrazinamide, a regimen including this drug was selected before M. tuberculosis was excluded and M. bovis BCG was identified. The anterior chest wall lesion was cleared 3 months after starting treatment. Since then, the patient has not visited the hospital for follow-up.

The Mycobacterium species that cause human and animal tuberculosis are grouped together within the MTC and include M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, M. canetti, M. caprae, M. pinnipedii, and M. mungi (1, 4). These species are closely related mycobacteria that exhibit remarkable nucleotide sequence homogeneity.

BCG is an attenuated derivative of a virulent strain of M. bovis. It has been used as a vaccine against M. tuberculosis, as a recombinant vehicle for multivalent vaccines against other infectious diseases, and as immunotherapy for cancers (3, 7). Disseminated BCG infection after vaccination most commonly occurs in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus infection or other causes of immunodeficiency (15). Various complications and adverse reactions have been reported after intravesical BCG instillation as treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (6, 11). Fever, hematuria, and cystitis are common adverse effects, while extravesical complications are considered to be rare, and a chest wall abscess like that in our case is extremely rare. To our knowledge, only two cases of subcutaneous nodules arising on the chest wall after intravesical BCG therapy have been reported previously (2, 9), but detailed molecular analysis was not performed in those cases.

In our case, we identified M. bovis BCG from the chest wall abscess by PCR-based MTC typing. The negative IGRA result which we obtained in the initial stage was correct because M. tuberculosis antigens were not present in BCG. We also confirmed that strain M9 derived from the abscess was identical to M. bovis BCG (Tokyo 172) by comparing the allelic profiles obtained from VNTR typing. Thus, the abscess was diagnosed as a complication of intravesical BCG at 1 year after instillation and antibiotic therapy was performed successfully based on that information. PCR-based genomic typing methods like deletion loci analysis and VNTR typing were mainly developed as tools for transmission surveys and population-based retrospective studies. However, genomic information can also be useful for clinical diagnosis and patient management. These techniques are also applicable to patients with MTC infection, including cases of dissemination, relapse, or exogenous reinfection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Kazuhiko Orikasa, Department of Urology, Kesennuma City Hospital, for his advice in this case.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexander KA, et al. 2010. Novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex pathogen, M. mungi. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:1296–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Armstrong RW. 1991. Complications after intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin: rhabdomyolysis and metastatic infection. J. Urol. 145:1264–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brosman SA. 1992. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy. Urol. Clin. North Am. 19:557–564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cousins DV, et al. 2003. Tuberculosis in seals caused by a novel member of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex: Mycobacterium pinnipedii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1305–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huard RC, de Oliveira Lazzarini LC, Butler WR, van Soolingen D, Ho JL. 2003. PCR-based method to differentiate the subspecies of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex on the basis of genomic deletions. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1637–1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lamm DL, et al. 1992. Incidence and treatment of complications of bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J. Urol. 147:596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lugosi L. 1992. Theoretical and methodological aspects of BCG vaccine from the discovery of Calmette and Guerin to molecular biology. A review. Tuber. Lung Dis. 73:252–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maeda S, et al. 2010. Beijing family Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from throughout Japan: phylogeny and genetic features. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:1201–1204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mangiarotti B, Trinchieri A, Marconato R, Pisani E. 2002. Skin abscess after intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin for prophylactic treatment of transitional cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 168:1094–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murase Y, Mitarai S, Sugawara I, Kato S, Maeda S. 2008. Promising loci of variable numbers of tandem repeats for typing Beijing family Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nikaido T, et al. 2007. Mycobacterium bovis BCG vertebral osteomyelitis after intravesical BCG therapy, diagnosed by PCR-based genomic deletion analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:4085–4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ritz N, et al. 2009. Susceptibility of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine strains to antituberculous antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:316–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roring S, et al. 2002. Development of variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium bovis: comparison of results with those obtained by using existing exact tandem repeats and spoligotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2126–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Supply P, et al. 2000. Variable human minisatellite-like regions in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Mol. Microbiol. 36:762–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Talbot EA, Perkins MD, Silva SF, Frothingham R. 1997. Disseminated bacille Calmette-Guérin disease after vaccination: case report and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:1139–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]