Abstract

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a major public health problem globally, especially because the bacterium has developed resistance to most antimicrobials introduced for first-line treatment of gonorrhea. In the present study, 96 N. gonorrhoeae isolates with high-level resistance to penicillin from 121 clinical isolates in Thailand were examined to investigate changes related to their plasmid-mediated penicillin resistance and their molecular epidemiological relationships. A β-lactamase (TEM) gene variant, blaTEM-135, that may be a precursor in the transitional stage of a traditional blaTEM-1 gene into an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), possibly causing high resistance to all extended-spectrum cephalosporins in N. gonorrhoeae, was identified. Clonal analysis using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) revealed the existence of a sexual network among patients from Japan and Thailand. Molecular analysis of the blaTEM-135 gene showed that the emergence of this allele might not be a rare genetic event and that the allele has evolved in different plasmid backgrounds, which results possibly indicate that it is selected due to antimicrobial pressure. The presence of the blaTEM-135 allele in the penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae population may call for monitoring for the possible emergence of ESBL-producing N. gonorrhoeae in the future. This study identified a blaTEM variant (blaTEM-135) that is a possible intermediate precursor for an ESBL, which warrants international awareness.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the causative agent of gonorrhea, which is the second most prevalent bacterial sexually transmitted infection globally. During recent decades, N. gonorrhoeae has rapidly developed resistance to most classes of antimicrobials used for treatment of gonorrhea (4, 6, 17, 18, 20). Penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG), with plasmid-mediated high-level resistance to penicillin, was first reported in 1976 (1, 14) and has since been disseminated worldwide (2). The first gonococcal strain with high-level clinical resistance to ceftriaxone, which is the last remaining option for first-line gonorrhea treatment, was recently found in Japan and completely characterized (9, 11). However, the resistance to ceftriaxone was chromosomally mediated, and no extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) has yet been identified in N. gonorrhoeae. If an ESBL did emerge in N. gonorrhoeae and spread internationally, gonorrhea would become an extremely serious public health problem.

PPNG strains are rare in Japan, but these strains have remained highly prevalent in several other countries in Asia (19) and worldwide (20). Penicillin is still also used as the first-line drug in, e.g., some Pacific island countries and the northern part of Australia, because of maintained efficacy in the settings and its low cost.

Although the β-lactamase (TEM) gene of authentic PPNG is the blaTEM-1 allele, a recently isolated PPNG in Thailand possessed the blaTEM-135 allele, which differs from the blaTEM-1 allele with one single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at position 539, resulting in a single amino acid substitution, M182T (16). However, the prevalence and characteristics of TEM-135 strains worldwide are unknown and seem critical to study, especially in countries where PPNG strains are highly prevalent. Furthermore, the knowledge regarding the genetic relationships of PPNG strains, their TEM genes, and plasmids carrying β-lactamase is highly limited.

Therefore, in the present study, PPNG isolates cultured from 2005 to 2007 in Thailand, which has a relatively high prevalence of PPNG, were investigated. To detect blaTEM-135 in the PPNG strains, a simple and rapid mismatch amplification mutation assay (MAMA) PCR method (3) was developed and successfully used. To reveal the population structure of the PPNG isolates, molecular epidemiological typing by means of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (5), porB gene sequencing, and N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing NG-MAST (7) were used to compare the detected TEM-135 strains with the TEM-1 strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

N. gonorrhoeae isolates were collected from Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand. Among 121 isolates collected during 2005 to 2007, based on resistance to penicillin and a positive nitrocefin test, a total of 96 PPNG isolates were detected and analyzed (see the supplemental material). These isolates were systematically collected in a previous research project (16).

DNA isolation.

To obtain genomic DNA, isolates were suspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and boiled for 10 min. After removing cell debris by centrifugation, the supernatant was used directly as template DNA in the PCR.

PCR identification of blaTEM gene.

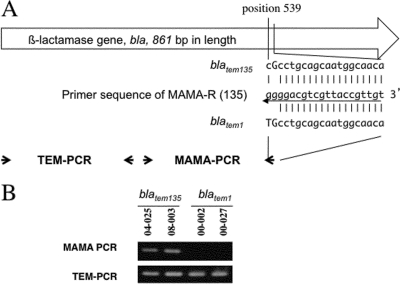

The MAMA-PCR to detect sequence polymorphism between the blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-135 alleles focused on nucleotide position 539 of the blaTEM gene (Fig. 1A). A conserved forward primer (MAMA-F, 5′-GCATCTTACGGATGGCATGAC-3′) and a blaTEM-135 allele-specific polymorphism detection primer (MAMA-R, 5′-TGTTGCCATTGCTGCAGGGG-3′) were designed (Table 1). The blaTEM-135 allele-specific primer carries a specific nucleotide, G (bold and underlined), at the 3′ end. Furthermore, to enhance the 3′ end mismatch effect, an additional nucleotide alteration of G, rather than C (bold), at the second nucleotide from the 3′ end of the primer was introduced. Thus, the blaTEM-135 allele-specific primer contained two mismatched bases at the 3′ end relative to the sequence of blaTEM-1 (Fig. 1A). In brief, the 10-μl-volume PCR master mix contained diluted template DNA, 0.8 μl of 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture (final concentration, 200 μΜ each), 0.25 μl each of 10 μM MAMA-F and MAMA-R primers (final concentration, 250 nM each), and 0.25 units of the DNA polymerase Takara Ex Taq (Takara Bio Co., Kyoto, Japan). The parameters of the PCRs were as follows: incubation for 2 min at 96°C followed by 25 cycles of 10 s at 96°C, 10 s at 56°C, and 30 s at 72°C and then final extension for 2 min at 72°C. The previously described N. gonorrhoeae strains NGON 00-002 and NGON 00-027 (containing blaTEM-1) and NGON 04-025 and NGON 08-003 (containing blaTEM-135) (10) were used as controls in all PCRs (Fig. 1). The universal TEM PCR was done as described above except that the PCR master mix contained TEM-F and TEM-R primers (Table 1). To confirm TEM alleles, we sequenced PCR-amplified products of the whole blaTEM coding region using the primer set bla-F and bla-R as described previously (10).

Fig 1.

MAMA-PCR for blaTEM-135 detection. (A) The TEM PCR primer set (TEM-F and TEM-R), which can amplify a 231-bp amplicon from blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-135, and the MAMA-PCR primer set, specific for blaTEM-135 (MAMA-F and MAMA-R), are shown schematically with arrows. The sequence of primer MAMA-R (middle) and the corresponding regions from blatem135 (top) and blatem1 (bottom) are also shown. (B) The PCR results for the Japanese penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) TEM-135 and PPNG TEM-1 isolates, which were used as controls in all PCRs, are presented.

Table 1.

Primers used in the MAMA-PCR for detection of blaTEM-135 and the TEM-PCR for detection of both blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-135

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Position |

|---|---|---|

| MAMA-F | GCATCTTACGGATGGCATGAC | 327-347 |

| MAMA-Ra | TGTTGCCATTGCTGCAGGGG | 558-539 |

| TEM-F | GTCGCCCTTATTCCCTTTTTTG | 22-43 |

| TEM-R | TAGTGTATGCGGCGACCGAG | 284-268 |

Binds only blaTEM-135.

Molecular epidemiological characterization.

Molecular epidemiological characterization by means of MLST (5), porB gene sequencing, and NG-MAST was performed as described previously (7). The type of plasmid carrying the β-lactamase (TEM) gene was determined by a multiplex PCR method developed by Palmer et al. (12). Neighbor-joining trees with por and tbpB nucleotide sequences were generated by using MEGA4.

Drawing of minimum spanning tree.

Based on the MLST data, a minimum spanning tree was generated by using BioNumerics (version 5.1; Applied Math), using the categorical coefficient of similarity and the priority rule of the highest number of single-locus variants as parameters. No hypothetical sequence or reported sequences other than those identified in the present study were included in the calculation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Development and use of the MAMA-PCR for detection of blaTEM-135.

To differentiate the blaTEM-135 allele from the blaTEM-1 allele in PPNG strains, by detection of the SNP at position 539, a MAMA-PCR (detecting only blaTEM-135) was successfully developed and was used together with a TEM PCR (detecting both blaTEM-135 and blaTEM-1) (Fig. 1).

Nine of the 96 PPNG isolates from Thailand were positive in both the MAMA-PCR and TEM PCR, suggesting that these isolates possessed the blaTEM-135 allele. Sequencing analysis of the full-length PCR products from the bla gene confirmed that these nine isolates (9.4%) indeed contained the blaTEM-135 allele, and the remaining 87 isolates (90.6%) possessed blaTEM-1.

Genetic relationships of PPNG TEM-1 and PPNG TEM-135 isolates.

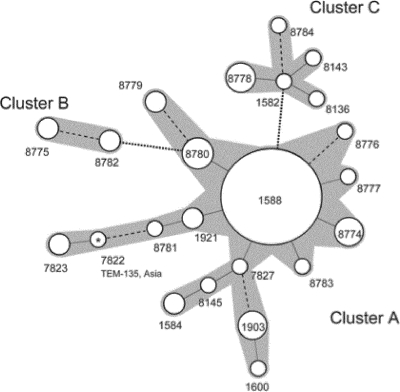

In order to examine the genetic relationships of PPNG isolates containing TEM-1 and TEM-135, MLST was carried out. Twenty-three MLST STs were identified among the 96 PPNG isolates, 17 STs among the TEM-1 isolates and 6 among the TEM-135 isolates. Among the 17 MLST STs identified among the TEM-1 isolates, ST1588 was the most prevalent (55 out of the 87 TEM-1 isolates, 63.2%) (Table 2). A minimum spanning tree analysis showed that most of the other STs in TEM-1 isolates were closely related to ST1588, with few exceptions (Fig. 2). Accordingly, 83 out of the 87 (95.4%) TEM-1 isolates belonged to a large cluster comprising 15 STs and centered around ST1588 (cluster A) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The remaining four TEM-1 isolates were assigned ST8782 (n = 2) and ST8775 (n = 2), which formed an additional smaller cluster (cluster B) (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Table 2.

MLST sequence type and plasmid type of PPNG isolates cultured in Thailand in 2005 to 2007a

| No. of isolates | MLST |

No. of isolates with plasmid typec: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | Clusterb | Africa | Asia | Toronto/Rio | |

| 55 | 1588 | A | 53 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 8780 | A | 5 | ||

| 4 | 1903 | A | 4 | ||

| 4 | 8774 | A | 4 | ||

| 2 | 1584 | A | 2 | ||

| 2 | 1921 | A | 2 | ||

| 2 | 8779 | A | 2 | ||

| 1 | 7827 | A | 1 | ||

| 1 | 8145 | A | 1 | ||

| 1 | 8776 | A | 1 | ||

| 1 | 8783 | A | 1 | ||

| 1 | 8777 | A | 1 | ||

| 2 | 7823 | A | 2 | ||

| 1 | 1600 | A | 1 | ||

| 1 | 7822 | A | 1 (1)d | ||

| 1 | 8781 | A | 1 | ||

| 2 | 8775 | B | 2 | ||

| 2 | 8782 | B | 2 | ||

| 4 | 8778 | C | 4 (4) | ||

| 1 | 1582 | C | 1 (1) | ||

| 1 | 8136 | C | 1 (1) | ||

| 1 | 8143 | C | 1 (1) | ||

| 1 | 8784 | C | 1 (1) | ||

| 96 | TOTAL | 79 | 8 (1) | 9 (8) | |

Fig 2.

Minimum spanning tree analysis of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) STs observed in penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae (PPNG) isolates cultured in Thailand in 2005 to 2007. Numbers beside the circles denote ST. Solid lines, dashed lines, and dotted lines show the interrelationship of “single-locus variant,” “double-locus variant,” and “triple-locus variant,” respectively. The types directly or indirectly connected through single- or double-locus-variant relationships were judged to form one cluster. Each cluster is shaded gray. Sizes of circles reflect the numbers of isolates belonging to each type (for details, see text and tables). The only PPNG TEM-135 isolate belonging to cluster A (ST7822) is marked with an asterisk, and its plasmid type is given.

Six different MLST STs were found in the nine TEM-135 isolates (Fig. 2 and Table 2). ST8778 was the most common (n = 4, 44.4%), and the other five STs were singletons. All these TEM-135 isolates, with the exception of the singleton ST7822 (isolate Thai_026) that was placed in the TEM-1 cluster A, belonged to the same separate cluster (cluster C) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Taken together, Thailand PPNG TEM-1 and PPNG TEM-135 strains seem to belong to distinct clonal groupings with different genetic backgrounds, and also, TEM-135 strains have emerged from multiple independent origins.

Plasmid typing.

Plasmid typing has been used as another classification method for PPNG surveillance. We also performed plasmid typing and investigated relationships with the results of MLST and the specific alleles of the bla genes blaTEM-1 and blaTEM-135.

As shown in Table 2, the Africa-type β-lactamase plasmid was the predominant type (79 of 96 isolates, 82.3%) in the isolates analyzed in the present study. Asia- and Toronto/Rio-type β-lactamase plasmids were found in only eight and nine isolates, respectively. Recently, a new type of the β-lactamase plasmid (Johannesburg plasmid) was reported by Muller et al. (8). If the Johannesburg-type plasmid had existed in our isolates, it would have generated a 450-bp amplicon with the BL1 and BL3 primers in our multiplex PCR system. However, we did not find any isolates containing this plasmid. Notable, all TEM-135 isolates, except Thai_026 (MLST ST7822) which had an Asia-type plasmid, carried the Toronto/Rio-type plasmid. As described above, Thai_026 (MLST ST7822) was the only isolate that belonged to cluster A formed by the TEM-1 isolates. Thus, the plasmid typing supported separation of this isolate from the other TEM-135 isolates, which further supports the hypothesis that TEM-135 strains have emerged from multiple independent origins. There was no TEM-135 isolate with the Africa-type plasmid. On the other hand, although all three plasmid types were found among the TEM-1 isolates, the Africa-type plasmid was the most abundant among the TEM-1 isolates (79 out of 87 isolates, 90.8%). Thus, this plasmid typing, again, implied a genetic difference of TEM-135 and TEM-1 strains. The most abundant MLST ST in TEM-1 isolates, ST1588, was strongly related to the Africa-type plasmid (53 out of 55 isolates, 96.4%). The remaining two MLST ST1588 isolates carried Toronto/Rio- and Asia-type plasmids, respectively. In total, the Africa-type plasmid was also abundant in other MLSTs, although both of the MLST ST8775 isolates had the Asia-type plasmid. Other isolates with the Asia-type plasmid were limited to MLST ST8781, MLST ST7822 (single TEM-135 isolate), MLST ST7823, and MLST ST1600 (Table 2). Interestingly, three of these MLST ST (except MLST ST1600) were linked and formed a stem in the left part of the minimum spanning tree (Fig. 2).

NG-MAST analysis.

To thoroughly evaluate the genetic diversity and relatedness of the TEM-135 isolates, all PPNG isolates were also analyzed using a substantially more discriminative typing method, NG-MAST (7). The 96 PPNG isolates were divided into 58 NG-MAST STs. Each NG-MAST ST is shown in the supplemental material.

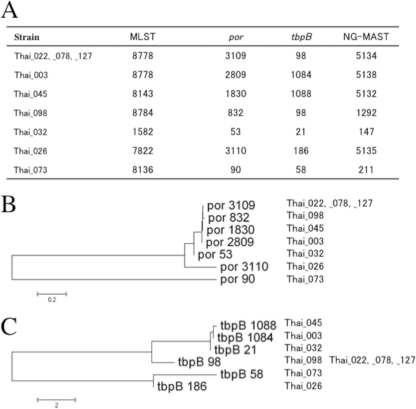

Among the four TEM-135 isolates assigned to MLST ST8788, three belonged to NG-MAST ST5134 (porB3109 and tbpB98; Fig. 3A), indicating clonal dissemination. Also, four of the additional TEM-135 isolates contained highly similar porB alleles (Thai_098, Thai_045, Thai_003, and Thai_032) (Fig. 3B). This similarity and, accordingly, the clustering were further supported by analyzing the tbpB alleles of all the TEM-135 isolates (Fig. 3C). Accordingly, the NG-MAST supported the conclusion that seven of the nine TEM-135 isolates had originated from a common ancestor. Both the remaining TEM-135 isolates (Thai_026 and Thai_073) were genetically separated from this cluster by the NG-MAST (Fig. 3). This was also in full concordance with the results of the MLST and plasmid typing (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Fig 3.

Molecular characterization of penicillinase-producing N. gonorrhoeae PPNG TEM-135 isolates. (A) Sequence types revealed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) are shown, along with por and tbpB alleles. (B and C) Neighbor-joining clustering showing similarity of por alleles (B) and tbpB alleles (C) from PPNG TEM-135 isolates.

Comparison of the Thai isolates with previously characterized Japanese PPNG isolates.

Using several molecular typing methods, we tried to identify any spread of PPNG between Thailand and Japan and found the possible spread of only one TEM-1 clone. Accordingly, the previously characterized Japanese isolates NGON 08-041 and NGON 08-046 (10) and Thai_036 and Thai_093 were all, in the present study, assigned to MLST ST1584 and NG-MAST ST1478 and carried the Africa-type plasmid with blaTEM-1. Despite some similarities in the MLST STs supporting, e.g., a cluster of isolates with the TEM-135 Toronto/Rio-type plasmid, no clear evidence to support international spread of any TEM-135 strains was found.

It is well-known that the β-lactamase plasmid can also easily be transferred between different N. gonorrhoeae strains. As the number of analyzed isolates in the present study was relatively low and they were cultured in restricted regions, Thailand (Bangkok) and Japan (Tokyo), more extensive international studies are crucial to reveal the origin and the evolutionary pathway of the TEM-135 strains, as well as the possible existence of PPNG with other TEM alleles.

Possible motive force of emergence of TEM-135.

Still, the reasons and mechanisms for the emergence and dissemination of PPNG TEM-135 strains are unknown. The blaTEM-135 allele was first found in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (13), and there are no major differences in the MICs of any β-lactam antimicrobials between blaTEM-135 and blaTEM-1 allele-possessing isolates. The blaTEM-135 allele has now been found in two different types of β-lactamase plasmid in PPNG, which are known to originally carry the blaTEM-1 allele. This fact indicates that blaTEM-135 emerged independently in N. gonorrhoeae and was not acquired due to, for example, a transformational event. However, due to the similar MICs of β-lactam antimicrobials in PPNG TEM-1 and TEM-135 isolates, other factor(s) than β-lactam antimicrobial selective pressure must be the selective force in the emergence of blaTEM-135. One possibility might be a pressure by other antibiotic(s) than penicillins. If so, we could expect some different patterns of resistance or rate of resistance to nonpenicillin antibiotics between TEM-1 and TEM-135 isolates. However, we did not observe any significant difference in those, at least when comparing susceptibility and resistance to ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline (data not shown). Another possibility is that this selective force may be an enhanced stability of the β-lactamase enzyme, which the TEM-135-specific amino acid substitution (M182T) is considered to establish (15, 21). Usually, this amino acid substitution is found in extended-spectrum TEM-type β-lactamase, as the second substitution. Since an amino acid substitution close to the active site of β-lactamase, which results in an increased MIC of cephalosporins, tends to decrease the stability of the enzyme, the M182T substitution may play a role as a stabilizer. In this context, the M182T in blaTEM-135 in PPNG might be a prerequisite to allow the subsequent substitutions, which could extend the antimicrobial resistance spectrum of the enzyme, like several TEM-type β-lactamases found in other bacteria, e.g., TEM-20 carriers.

Necessity of monitoring TEM-135 PPNG.

In conclusion, an emergence of ESBL-producing N. gonorrhoeae would be highly threatening to public health, because this would also be resistant to ceftriaxone, which is the first-line and last remaining option for treatment of N. gonorrhoeae infection in many countries worldwide. Recently, the first N. gonorrhoeae strain with chromosomally mediated high-level resistance to ceftriaxone was isolated in Japan (9, 11). Although this strain was not PPNG, i.e., it had a penA-dependent resistance mechanism, this calls for a substantially strengthened monitoring of ceftriaxone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae infection and gonorrhea treatment failures, including consideration of possible emergence of ESBL-producing N. gonorrhoeae isolates.

In Thailand, about 10% of PPNG had TEM-135, a possible direct precursor of an ESBL. However, the prevalence and characteristics of TEM-135 strains and possible strains containing other TEM variants worldwide is unknown. This seems crucial to investigate in larger, international studies, including studies of recent geographically, phenotypically, and genetically diverse PPNG.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Makiko Itoh and Haruka Tsuruzono for technical assistance.

This work was partly supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (grants H21-Shinkou-Ippan-001 and H23-Snikou-Shitei-020).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashford W, Golash R, Hemming V. 1976. Penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Lancet 308: 657–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1979. Penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae—United States, worldwide. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 28: 85–87 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cha RS, Zarbl H, Keohavong P, Thilly WG. 1992. Mismatch amplification mutation assay (MAMA): application to the c-H-ras gene. PCR Methods Appl. 2: 14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deguchi T, Nakane K, Yasuda M, Maeda S. 2010. Emergence and spread of drug resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Urol. 184: 851–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jolley KA. 2001. Multi-locus sequence typing. Methods Mol. Med. 67: 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis DA. 2010. The gonococcus fights back: is this time a knock out? Sex. Transm. Infect. 86: 415–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin IMC, Ison CA, Aanensen DM, Fenton KA, Spratt BG. 2004. Rapid sequence-based identification of gonococcal transmission clusters in a large metropolitan area. J. Infect. Dis. 189: 1497–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muller EE, Fayemiwo SA, Lewis DA. 2011. Characterization of a novel β-lactamase-producing plasmid in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: sequence analysis and molecular typing of host gonococci. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66: 1514–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ohnishi M, et al. 2011. Is Neisseria gonorrhoeae initiating a future era of untreatable gonorrhea?: detailed characterization of the first strain with high-level resistance to ceftriaxone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55: 3538–3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohnishi M, Ono E, Shimuta K, Watanabe H, Okamura N. 2010. Identification of TEM-135 β-lactamase in penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54: 3021–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohnishi M, et al. 2011. Ceftriaxone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Japan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17: 148–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palmer HM, Leeming JP, Turner A. 2000. A multiplex polymerase chain reaction to differentiate β-lactamase plasmids of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45: 777–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasquali F, Kehrenberg C, Manfreda G, Schwarz S. 2005. Physical linkage of Tn3 and part of Tn1721 in a tetracycline and ampicillin resistance plasmid from Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55: 562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillips I. 1976. Beta-lactamase-producing, penicillin-resistant gonococcus. Lancet 308: 656–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sideraki V, Huang W, Palzkill T, Gilbert HF. 2001. A secondary drug resistance mutation of TEM-1 β-lactamase that suppresses misfolding and aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98: 283–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Srifeungfung S, et al. 2009. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in HIV-seropositive patients and gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility: an update in Thailand. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 62: 467–470 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tapsall J. 2006. Antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is diminishing available treatment options for gonorrhea: some possible remedies. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 4: 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tapsall JW. 2009. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and emerging resistance to extended spectrum cephalosporins. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tapsall JW, et al. 2010. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific and South East Asian regions, 2007–2008. Commun. Dis. Intell. 34: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tapsall JW, Ndowa F, Lewis DA, Unemo M. 2009. Meeting the public health challenge of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 7: 821–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang X, Minasov G, Shoichet BK. 2002. Evolution of an antibiotic resistance enzyme constrained by stability and activity trade-offs. J. Mol. Biol. 320: 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.