Abstract

Treatment of Clostridium difficile is a major problem as a hospital-associated infection which can cause severe, recurrent diarrhea. The currently available antibiotics are not effective in all cases and alternative treatments are required. In the present study, an ovine antibody-based platform for passive immunotherapy of C. difficile infection is described. Antibodies with high toxin-neutralizing titers were generated against C. difficile toxins A and B and were shown to neutralize three sequence variants of these toxins (toxinotypes) which are prevalent in human C. difficile infection. Passive immunization of hamsters with a mixture of toxin A and B antibodies protected them from a challenge with C. difficile spores in a dose-dependent manner. Antibodies to both toxins A and B were required for protection. The administration of toxin A and B antibodies up to 24 h postchallenge was found to reduce significantly the onset of C. difficile infection compared to nonimmunized controls. Protection from infection was also demonstrated with key disease isolates (ribotypes 027 and 078), which are members of the hypervirulent C. difficile clade. The ribotype 027 and 078 strains also have the capacity to produce an active binary toxin and these data suggest that neutralization of this toxin is unnecessary for the management of infection induced by these strains. In summary, the data suggest that ovine toxin A and B antibodies may be effective in the treatment of C. difficile infection; their potential use for the management of severe, fulminant cases is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium that continues to be a significant burden to hospitals and long-term health care facilities. C. difficile infection (CDI), caused by ingested spores, is usually preceded by the use of antibiotics which perturb the normal gut flora and allow the bacterium to colonize the digestive tract and elaborate its cytotoxins which damage the gut epithelium (4, 23). Symptoms of CDI range from mild, self-limiting diarrhea to life-threatening colitis (3). The number of cases of CDI has increased significantly over the past 10 years; this is due in part to the appearance of more virulent strains of the bacterium (22). While improved management of CDI has significantly reduced the incidence of the disease within the United Kingdom, there were 25,604 cases reported between April 2009 and March 2010, and in 2009, CDI was a contributing factor to 3,933 deaths. In the United States, the mortality rate of CDI increased from 5.7 per million in 1999 to 23.7 per million in 2004, and it has been described as the “silent epidemic” causing more deaths than all other intestinal diseases combined and costing the health care system over $3 billion (26, 27).

Two large protein cytotoxins, toxins A and B, are recognized as the principal virulence factors of C. difficile, and these act via a complex, multistep mechanism to damage the integrity of the gut mucosa (13). Both have been shown to mediate their action via disruption of the cell cytoskeleton by the glucosylation of the Rho family of GTPases. Some C. difficile strains also have the capacity to produce a binary toxin structurally similar to Clostridium perfringens iota toxin. The role of the binary toxin in the pathogenesis of CDI is unclear, but a possible role as an additional colonization factor has been recently proposed (36). Sequence variations in the 19.6-kb region (PaLoc) of the chromosome, which encodes toxins A and B (5), have been identified, and these variants, termed toxinotypes, may result in sequence differences between the toxins (31, 32). Indeed, comparison of the amino acid sequence of toxinotype 0 toxin B with that of toxinotype 3 reveals a 7.8% heterology overall and 13% heterology within the immunodominant C-terminal repeat region. At present, over 30 toxinotypes have been identified, but the extent of the sequence diversity, which appears to be higher within the toxin B family, has not been fully characterized.

Treatment of CDI currently relies on the use of antibiotics, primarily metronidazole and vancomycin. Although these are successful in treating the majority of cases, there are areas of disease management in which they do not have the desired efficacy (10, 24). Metronidazole and vancomycin are less effective at managing severe, fulminant CDI, where high-risk surgery (colectomy) is often the only treatment option. The rate of recurrence of CDI after use of these antibiotics (20 to 30%) is also unacceptable and is due in part to the continued disruption of the normal gut flora by such antibiotic treatment (1, 10). Consequently, several alternative therapies are under development, including new, more selective antibiotics and several strategies directed at neutralizing the activities of the primary virulence factors, toxins A and B (10). In the latter category are toxin-binding agents designed to mop up the toxins in the alimentary canal, vaccines formulated to elicit a toxin-neutralizing immune response, and antibodies with toxin-neutralizing activity to confer immunity via passive immunization. Of these, the toxin-binding agents (e.g., tolevamer) have failed to demonstrate the desired efficacy in clinical trials (42), while the antibody-based approaches are showing more promise.

Several reports indicate that antibodies to toxin A and toxin B can prevent disease in animal models (11, 14, 20). More recently, these findings were confirmed by Babcock et al. (2), who, using an epidemic strain of C. difficile, demonstrated that humanized monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against toxins A and B, when administered to hamsters, prevented the onset of CDI. In a recent phase 2 clinical trial, MAbs were also shown to reduce the rate of recurrence of CDI from 25% in the placebo group to 7% in the treated group (19). It remains to be seen whether or not a therapeutic strategy which relies on a single MAb to neutralize each toxin will be effective against the numerous toxinotypes of toxins A and B that are emerging. Vaccines, based on toxin A- and B-derived antigens, are also a potentially viable strategy to provide at-risk patient groups with protection against CDI, and a clinical study using a small number of patients that were immunized with formaldehyde-inactivated toxins A and B showed the efficacy of the approach in preventing CDI recurrence (38). Larger, controlled trials are required to establish whether or not vaccination can generate the required immune response in elderly patients, who are most at risk from CDI.

In the present study, we describe the potential of ovine antibodies for the management of CDI. Ovine antibodies have been used widely clinically to treat intoxication (snake bite victims, drug overdose) and are well tolerated in humans (8, 28, 35). In general, polyclonal antibodies are particularly effective at neutralizing and clearing toxins from the bloodstream, and their diverse composition makes them efficient at neutralizing toxin families, such as C. difficile toxins A and B, where there is a significant level of sequence diversity. In the present study, we describe the production of ovine antibodies with high toxin-neutralizing titers to toxins A and B and demonstrate their efficacy in vivo to prevent CDI induced by a range of key C. difficile disease isolates. The potential clinical applications of ovine antibodies in the treatment of CDI are also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and typing.

C. difficile VPI10463 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (42355), C. difficile ribotype 027 (NCTC 13366) was a gift from the Anaerobe Reference Laboratory, Cardiff, United Kingdom, and C. difficile ribotype 078 (clinical isolate) was obtained via the C. difficile Ribotyping Network (SE Region, Southampton, United Kingdom). For long-term storage the strains were stored in supplemented brain heart infusion broth (sBHI) plus 10% dimethyl sulfoxide in liquid nitrogen. For short-term storage, they were maintained on Fastidious Anaerobe agar (FAA; Oxoid) with horse blood in an anaerobic atmosphere at 4°C. All C. difficile strains used in the study were toxinotyped according to previously described methods (32).

Toxin production and purification.

C. difficile toxins A and B were purified essentially as described previously (29) with some modifications. Starter cultures (5 ml) of the C. difficile strain were used to inoculate each of eight 2-liter vessels containing dialysis sacs (60 ml), and these were grown under anaerobic conditions for 90 to 96 h at 37°C. The contents of the dialysis sacs were then pooled, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min, and diluted 1:2 (vol/vol) with 50 mM bis-Tris buffer pH 6.5, and the pH adjusted to 6.5. The diluted culture supernatant was applied onto a Q Sepharose column equilibrated in 50 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.5) buffer and toxins A and B protein peaks eluted by a NaCl gradient. Toxin A, which eluted between 200 and 300 mM NaCl, was purified further by chelating Sepharose Fast Flow chromatography as described previously (29). Toxin B, which eluted between 500 and 700 mM NaCl, was further purified by chromatography on Mono-Q (column size, 8 ml), equilibrated in 50 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.5) buffer, and eluted with a linear NaCl gradient. For the preparation of toxin A or B toxoids, 1-mg ml−1 solutions of toxins in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM) containing 150 mM NaCl were made 0.2% (vol/vol) with respect to formaldehyde and incubated at 37°C for 7 days and then stored at 4°C.

Recombinant antigens.

Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) was used for cloning and preparation of purified plasmid DNA. E. coli BL21(DE3) and BL21 Star (DE3) (Invitrogen) were used as expression hosts for recombinant toxin fragments. The gene encoding the C-terminal repeat region of toxin B (amino acid [aa] residues 1755 and 2366) was amplified from the genomic DNA of C. difficile VPI10463 (Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit), and the genes coding the N-terminal fragment of toxin B (aa residues 1 to 544) and the C-terminal repeat region of toxin A (aa residues 1825 to 2710) were obtained synthetically (Entelechon GmbH). The genes were cloned into a modified pMAL-HT expression vector (pMAL-c2 backbone with maltose-binding protein removed and substituted with a His6 tag), and transformants were grown in Terrific Broth at 37°C. Gene expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) using standard methods. The cells were broken using Bugbuster reagent (Merck), and expressed proteins were purified to >90% homogeneity by a combination of immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (Ni-Sepharose; eluted with a 20 to 500 mM imidazole gradient) and ion-exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose).

Production of ovine antiserum and antibodies.

Antigens (doses between 5 and 250 μg) were mixed thoroughly with Freund's adjuvant (ca. 50% final volume) and administered into each of three sheep across six sites, including the neck and the upper limbs. The complete form of the adjuvant was used for the primary immunization, and incomplete Freund's adjuvant was used for all subsequent boosts, which were performed at 28-day intervals. Three sheep were used per antigen, and blood samples were taken 14 days after each immunization. Once adequate antibody levels were achieved, larger volumes of blood were taken (10 ml/kg of body weight) into sterile bags. After collection, these were rotated slowly to accelerate clotting then centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g, and the serum was removed under aseptic conditions and pooled. IgG was purified using caprylic acid precipitation. Serum was diluted with an equal volume of 153 mM NaCl, and caprylic acid was added to a final concentration of 2% (wt/vol) with rapid stirring for 30 min and then left to stand for further 60 min. The product was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 h, and the supernatant fluid, containing the immunoglobulins, was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and then dialyzed against sodium citrate buffer (20 mM, pH 5.8) containing 153 mM NaCl. Finally, the purified IgG was filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter and stored at 4°C.

Antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Assays were carried out on microtiter plates coated with either toxin A or B (100 μl/well, 5 μg ml−1) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After coating, plates were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked for 1 h at 37°C with the same buffer containing 5% fetal bovine serum (blocking buffer). Blocked plates were washed with PBST and incubated with various dilutions of ovine serum or purified antibody (50 μl/well), prepared in blocking buffer, for 1 h at 37°C, after which they were washed and incubated with a rabbit anti-ovine horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Sigma S1265; 1/5,000 diluted with blocking buffer) for 1 h at 37°C. After further washing, a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate system was added, and the plates read at 450 nm in a microtiter plate reader. Antibody dilution titers (endpoint at 0.2 absorbance units above background values) were estimated in duplicate.

Toxin neutralization assay.

A cell-based neutralization assay was performed to assess the efficacy of sheep antisera/IgG to neutralize the toxic activity of toxins A and B. The assay was performed using monolayer cultures of Vero cells maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) supplemented with fetal calf serum (10%) and glutamine (2 mM) in a 96-well microtiter plate (104 cells/well) essentially as described previously (29). Dilutions of the antisera and antibodies, made with DMEM plus 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), were mixed with an equal volume of either toxin A or toxin B (50- and 0.5-ng/ml final concentrations on cells, respectively), followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. These were then applied to cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. After overnight incubation, the cells were assessed by microscopy for rounding, and the highest serum/IgG dilution providing complete protection from the cytotoxic activity of toxin A or B was recorded as the neutralization titer. All cytotoxicity assays were performed in duplicate.

Preparation of C. difficile spores.

Spores for in vivo studies were prepared from C. difficile strains which had been both ribotyped and toxinotyped (32) to confirm their identity. For crude spore production, 80 ml of reduced sBHI broth was inoculated with C. difficile, followed by incubation at 37°C for 48 h under anaerobic conditions. The culture was spread onto each of 15 reduced FAA plates (300 μl/plate), and these were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 10 days, after which the cell layer was removed from the plates using sterile cotton wool swabs and transferred to 15 ml of sterile DMEM. The crude spores were recovered by centrifugation, washed twice with DMEM, and resuspended in 12 ml of DMEM prior to heat shock (62°C for 40 min) to kill vegetative cells. The crude spore preparation was quantified by the Miles and Misra viable count technique using FAA plates, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C.

Animal model for C. difficile infection.

Syrian hamsters (80 to 100 g) were housed (two animals per cage) in isolator cages fitted with air filters on their lids to minimize contamination between groups. Groups of 14 hamsters were divided into a “test” subgroup of 10 and a “control” subgroup of 4 animals as described previously (15). In some experiments, control groups were increased in size to allow blood samples to be taken at designated times for the measurement of toxin-neutralizing titers. All hamsters were weighed and administered clindamycin (2 mg in 0.2 ml of sterile H2O) by the orogastric route on day 0. On day 2 or 3, hamsters in the test subgroup were challenged with between 102 and 103 CFU of C. difficile spores in 0.2 ml of DMEM, given orogastically. All animals were weighed daily and monitored six times/day for up to 21 days for disease symptoms, which included diarrhea, weight loss, lethargy, and tender abdomen (2, 33). Hamsters were scored on a 0 to 3 scale for disease symptoms, and animals in advanced stages of disease were euthanized. Survival curves were analyzed by log-rank tests (nonparametric distribution analysis, right censoring). For passive immunization studies, ovine IgG was purified from sera generated by using the toxoids derived from toxins A and B. Various doses were administered at various times by the intraperitoneal route. Toxin-neutralizing titers of purified IgG preparations were determined using the toxin-neutralizing assay described above. Neutralizing units for toxin A and B purified antibodies were defined as the quantity of IgG that could completely neutralize the cytotoxic effects on Vero cells of toxin A at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml and toxin B at a final concentration of 0.5 ng/ml.

RESULTS

Production and assessment of antibodies to toxins A and B.

The biological actions of both toxins A and B are capable of causing extensive damage to the gut mucosa via their potent cytotoxic actions. It is therefore essential that antibody preparations that are to be evaluated for their potential immunotherapeutic value have the capacity to neutralize these cytotoxic activities as measured by cell-based toxin-neutralization assays. In initial studies, recombinant antigens based on the N-terminal effector domain of toxin B (residues 1 to 544) and the C-terminal binding domains of toxins A and B (residues 1825 to 2710 and 1755 to 2366, respectively) were purified and used to immunize guinea pigs and sheep. While the resulting antisera were found to have high ELISA titers of 105 to 106 against their respective toxins, the toxin-neutralizing titers, measured in cell-based assays, were low (≤10 U) for all fragments tested. In view of the low efficiency of the available recombinant antigens to evoke toxin-neutralizing immune responses, the native toxins A and B and their derived toxoids were assessed as immunogens. Table 1 summarizes the ovine antibody responses to toxin A and its formaldehyde-inactivated toxoid. A lower immunizing dose of toxin A was used compared to the toxoid to reduce the incidence of adverse effects of its biological activity. Although high ELISA titers were obtained with both the toxin and the toxoid immunogens, only the latter elicited a potent toxin-neutralizing immune response. These data clearly show a lack of correlation between ELISA and the toxin-neutralizing titers obtained with the cell-based assay. Similar data were obtained with toxin B antigens, and a potent toxin-neutralizing immune response was obtained only with the toxoid (Table 2). As observed for toxin A, there was a poor correlation between the antibody ELISA and toxin-neutralizing titers. Whereas the ovine anti-toxins A and B showed a degree of cross-reactivity by ELISA, their toxin-neutralizing activities were specific to the immunizing antigen. An ovine anti-toxin A serum which neutralized toxin A with a titer of 16,000, neutralized toxin B with a titer of <10 U. Similarly, an ovine anti-toxin B serum that neutralized toxin B with a titer of 20,000 neutralized toxin A with a titer of <10 U.

Table 1.

Ovine antibody response to toxin A antigens

| No. of dosesa | Immunization period (wks) | Antibody neutralizing titerb |

Antibody ELISA titer |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin | Toxoid | Toxin | Toxoid | ||

| 0 | 0 | <10 | <10 | ND | ND |

| 1 | 0 | <10 | <10 | ND | ND |

| 2 | 6 | <10 | 2,000 | 1 × 105 | 1 × 105 |

| 3 | 10 | <10 | 4,000 | 1 × 105 | 3 × 105 |

| 4 | 14 | 200 | 16,000 | 3 × 105 | 1 × 106 |

Toxin (5 μg), toxoid (50 μg).

For each antigen, three sheep were immunized, and ELISA and neutralizing antibody titers were determined in duplicate using pooled serum (equal volumes) from each animal. Neutralizing titers were derived by measuring the capacity of a dilution of antiserum to completely protect Vero cells from a fixed concentration of toxin. Toxin A was fixed at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml, and toxin B was fixed at a final concentration of 0.5 ng/ml. These different levels reflect the 50- to 100-fold-higher cytotoxic activity of toxin B compared to toxin A. ND, not determined.

Table 2.

Ovine antibody response to toxin B antigens

| Immunizing antigen | Immunization period (wks) | Dose (μg)a | Neutralizing titerb (at wk 14) | Antibody ELISA titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxin B | 14 | 5 | <10 | 2 × 104 |

| Toxoid B | 14 | 50 | 4,000 | 2 × 105 |

| Toxoid B (dose ranging study) | 14 | 10 | 1,000 | 3 × 105 |

| 14 | 50 | 4,000 | 3 × 105 | |

| 14 | 250 | 20,500 | 7 × 105 |

n = four doses for each study.

As defined in Table 1.

Studies were also performed to assess whether the above ovine antibody preparations, which were raised against toxinotype 0 toxins A and B, could adequately neutralize toxins produced by toxinotypes 3 and 5 C. difficile strains. These studies, which focused on toxin B, the most sequence diverse of the two toxins, are summarized in Table 3 and show unreduced neutralizing potency against toxinotype 3 toxin B, while that against toxinotype 5 toxin B was reduced 2-fold.

Table 3.

Assessment of the efficiency with which ovine antibodies raised against toxin B toxinotype 0 are able to neutralize toxin B toxinotypes 3 and 5

| Toxinotype | Ovine anti-toxin B neutralization titera |

|

|---|---|---|

| 4 U of toxin B | 10 U of toxin B | |

| Toxin B, toxinotype 0 | 2,560 | 1,280 |

| Toxin B, toxinotype 3 | 2,560 | 1,280 |

| Relative titer (0:3) | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| Toxin B, toxinotype 0 | 2,560 | 1,280 |

| Toxin B, toxinotype 5 | 1,280 | 640 |

| Relative titer (0:5) | 2:1 | 2:1 |

One toxin unit is defined as that which induces 100% cell death in cytotoxicity assays in 24 h.

Protection from CDI by passive immunization with a mixture of toxin A and B antibodies.

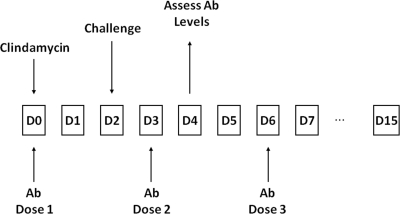

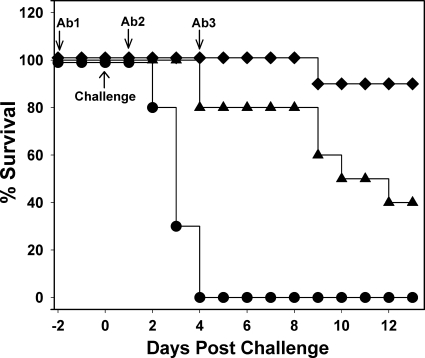

For initial studies, C. difficile VPI10463 strain was used, since this strain is a high toxin producer and induces a rapid onset of CDI symptoms in the hamster model. Passive immunization studies were performed by the protocol outlined in Fig. 1 and antibody administered at doses of 2.5 and 25 mg of IgG. All animals in a nonimmunized control group succumbed to severe CDI within 5 days postchallenge and showed classic symptoms of CDI (diarrhea, weight loss) (Fig. 2). In the antibody-treated groups, 90 and 40% of the animals survived in the high- and low-antibody-dose groups, respectively, and at 12 days postchallenge all surviving animals were asymptomatic. These data show that passive immunization with a mixture of antibodies to toxins A and B afford protection against CDI induced by a challenge of C. difficile spores. Log-rank analysis of survival curves showed that protection provided by both antibody doses was statistically significant (P < 0.001) compared to the nonimmunized control group. The level of protection also appeared to be dose dependent. Toxin-neutralizing titers of blood samples, pooled from four immunized animals at the time indicated in Fig. 1, were also estimated. At the high antibody dose, neutralizing titers for toxins A and B were 640 and 80 U/ml, respectively. At the low antibody dose, neutralizing titers for toxins A and B were 80 and 20 U/ml, respectively. These data are approximately consistent with the ratio of antibody titers within the administered mixture. Thus, at the lower antibody dose, which provided some protection against infection, there was sufficient antibody per ml to neutralize ∼4 μg of toxin A and ∼10 ng of toxin B. In a repeat study, similar results were obtained, and the surviving animals remained asymptomatic at 21 days postchallenge (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Schematic of passive immunization study. Ovine antibody (Ab) was administered on the days indicated.

Fig 2.

Protection from CDI by passive immunization with ovine antitoxin A/B. Graph shows survival postchallenge with C. difficile VPI 10463 spores in the hamster model. Animals were administered with IgG preparations purified from antisera raised using toxoid, and the specific neutralizing titers for toxins A and B were 800 and 100 U/mg, respectively. Three doses of antibody were administered as indicated, and each consisted of the following: ♦, 25 mg of antitoxin A/B IgG (1 × 104 U for toxin A, 1.3 × 103 U for toxin B); ▴, 2.5 mg of antitoxin A/B IgG (1 × 103 U for toxin A, 1.3 × 102 U for toxin B); and •, 12.5 mg of nonspecific ovine IgG. Comparison of survival curves by log-rank analysis showed that for “♦” and “▴” values P < 0.001 compared to the control group (•).

Contribution of toxin A and B antibodies to protection against CDI.

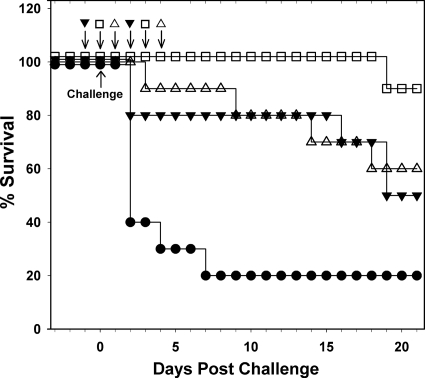

With conflicting reports in the literature concerning the importance of toxin A to the development of CDI (16, 21), studies were undertaken to assess the contribution of toxin A and B antibodies for protection against infection. Antibody preparations used were shown to neutralize specifically the activities of either toxin A or B with little or no cross-neutralizing activity. The onset of CDI in the nonimmunized control group was rapid in the present study with 100% of animals developing severe infection within 2 days postchallenge (Fig. 3). The severity of the disease onset may account for the higher than expected mortality of 50% in the study group which received antibodies to both toxins A and B. All of the animals that received just antibodies to toxin A, succumbed to severe disease, but at a slower rate (P < 0.001) than the nonimmunized controls, while hamsters receiving just antibodies to toxin B, became infected at a similar rate to the nonimmunized controls (P = 0.56). Thus, while the presence of antibodies to toxin A slowed down the onset of CDI, antibodies to toxin B appeared to offer no protection, which suggests that toxin A is a determinant of severe CDI as well as toxin B.

Fig 3.

Requirement of toxin A and B antibodies for protection from CDI. The graph shows survival postchallenge with C. difficile VPI 10463 spores in the hamster model. Animals were administered with IgG preparations purified from antisera raised using toxoid, and the specific neutralizing titers for toxins A and B were 800 and 400 U/mg, respectively. Animal groups were administered with three doses of antibody as indicated, and each consisted of the following: ▾, 25 mg of antitoxin A/B IgG (1 × 104 U for toxin A, 5 × 103 U for toxin B); ▵, 25 mg of anti-toxin A IgG (2 × 104 U); ○, 25 mg of anti-toxin B (1 × 104 U); and ☐, 12.5 mg of nonspecific ovine IgG. Log-rank analysis showed that for “▾” and “▵” values P < 0.001 compared to the controls (☐) and for “○” values P = 0.56.

Protection from challenge with C. difficile ribotype 027 and 078 strains.

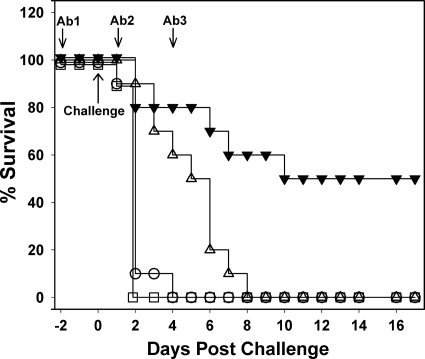

Immunotherapeutics must display efficacy against a broad range of disease isolates to be effective clinically. Protection was therefore assessed against challenge with ribotype 027 and 078 C. difficile strains which produce toxinotype 3 and 5 toxins, respectively. Both of these disease isolates are members of the “hypervirulent” clade and are able to produce an active binary toxin in addition to toxins A and B (39). For both strains, 80% of nonimmunized control groups developed severe disease within 11 days postchallenge, whereas for the passively immunized groups, 90 and 100% were protected from infection induced by the ribotype 027 and 078 strains, respectively (Fig. 4). Surviving animals were asymptomatic during the course of the experiment. The data show that antibodies raised against toxinotype 0 toxins A and B have protective efficacy against strains producing toxinotype 3 and 5 toxins. They also suggest that the inclusion of antibodies to neutralize any binary toxin produced by these strains may not be required.

Fig 4.

Protection from challenge with 027 and 078 ribotype C. difficile strains. Graphs show the survival postchallenge with C. difficile 027 spores (A) and 078 spores (B) in the hamster model. IgG preparations were as described in Fig. 2. Animal groups were administered with 3 doses of antibody as indicated, and each consisted of the following: ▾, 25 mg of antitoxin A/B IgG (1 × 104 U for toxin A, 1.3 × 103 U for toxin B), or • and ■, 12.5 mg of nonspecific ovine IgG. A comparison of antibody-treated and control survival curves by log-rank analysis showed that P = 0.002 (A) and P < 0.001 (B).

Protective effects of antibodies administered postchallenge with C. difficile.

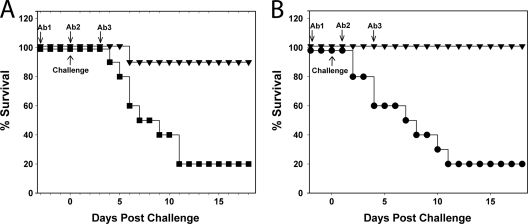

To assess the therapeutic window for passive immunization, the efficacy of antibodies directed against toxins A and B to protect animals from CDI when administered at various times after challenge with C. difficile spores was assessed. In the present study, antibody doses were reduced to two (72 h apart) and for the “treatment” groups, the first of these was administered at either 5 or 24 h postchallenge (Fig. 5). Of the nonimmunized control group, 80% developed severe infection within 7 days of challenge. The highest level of protection was observed in the treatment group, which was given antibody 5 h postchallenge and in which only 10% of animals developed CDI. The onset of infection in the treatment group in which antibody therapy was initiated 24 h postchallenge was also significantly reduced compared to the control group (P = 0.016). Overall, the data suggest that antibody treatment which is initiated after challenge is effective in reducing CDI.

Fig 5.

Protective effects of toxin A and B antibodies administered after challenge. Graph shows survival postchallenge with C. difficile VPI 10463 spores in the hamster model. IgG preparations were as described in Fig. 3. Antibody treatment (two doses of 25 mg of antitoxin A/B IgG, administered 72 h apart, each containing 1 × 104 U for toxin A and 5 × 103 U for toxin B) was initiated: ▾, 24 h prechallenge; ☐, 5 h postchallenge; or ▵, 24 h postchallenge. A control group (•) received no antibody treatment. A comparison of survival curves by log-rank analysis showed that for “☐” values P = 0.001, for “▵” values P = 0.016, and for “▾” values P = 0.061 compared to the control group.

DISCUSSION

Over the past 10 years, infection by C. difficile has become a serious problem within health care environments, and the bacterium has achieved “superbug” status, causing and contributing to many thousands of deaths within the developed world (6). Alternatives to the current antibiotic therapies are urgently required, particularly with respect to the management of severe, fulminant CDI and also for reducing rates of disease recurrence which, at 20 to 30%, are unacceptably high.

Previous studies to develop antibody-based therapies for CDI have demonstrated that passive immunization with antibodies to toxins A and B can prevent infection in animal models (2, 11, 14, 20). These studies have focused on two main strategies: the oral administration of either avian IgY (14) or bovine colostrum or whey protein concentrate (40) and the parenteral administration of humanized MAbs directed against toxins A and B (2, 19). Both approaches appear best suited to preventing the recurrence of CDI rather than treating severe, fulminant CDI. Thus, oral antibody delivery may not be appropriate in severe CDI due to obstruction of the lower bowel and the systemic intoxication which are frequent manifestations of this condition (34). While MAbs offer a potentially viable option for the treatment of severe disease, they must be capable of quickly neutralizing and clearing all of the toxins. This may be difficult to achieve if only one MAb per toxin is used. In the present study, we describe the production of ovine antibodies with high neutralizing activities against toxins A and B and demonstrate their efficacy at preventing infection induced by key epidemic strains.

Recombinant fragments of toxins A and B representing either all or a proportion of their receptor binding domains have been used in previous studies to generate toxin-neutralizing antibodies (14, 41). In the present study, we found that toxin A and B fragments representing the entire C-terminal repeat, receptor-binding component of these toxins were poor at generating toxin-neutralizing antibodies in both guinea pigs and sheep, as measured by a stringent cell-based assay using complete cell protection as the endpoint. That these fragments generated antisera with high ELISA titers demonstrated that they were immunogenic, and it is possible that neutralizing epitopes within these fragments are poorly presented to the immune system. These data are consistent with a recent study in which a panel of single-domain antibodies targeting the cell-receptor binding domain of toxin B had little neutralizing activity either singularly or in combination (12). Ovine antisera of high toxin-neutralizing titers were obtained with the formaldehyde inactivated toxins A and B. Although these antisera showed cross-reactivity between toxins A and B by ELISA, which is consistent with the presence of common epitopes as shown by previous studies (30), toxin-neutralizing activity was highly specific to the homologous toxin, confirming previous findings that the dominant neutralizing epitopes are specific to each toxin (17). Whereas immunization with toxoids generated an antiserum with a high neutralizing titer, immunization with the native toxins, although generating an adequate immune response as measured by the ELISA titer, resulted in antisera with a relatively poor neutralizing titer. The reasons for this are unclear, but suboptimal presentation of the toxins to cells of the immune system or detrimental effect of their cytotoxic actions cannot be discounted.

For initial passive immunization studies, C. difficile strain VPI10463 was chosen because of its capacity to produce high levels of toxins A and B and hence provide a stringent test of any toxin-directed therapy. Passive immunization studies using a mixture of ovine toxin A and B antibodies showed protection from CDI in a dose-dependent manner and it is notable that, at the highest antibody dose administered, the majority of the animals remained free of infection at >2 weeks postchallenge. The mechanism by which parenterally administered circulating antibodies neutralize toxins produced by a gut pathogen is currently unclear. It is possible that the disruption of the cell cytoskeleton by toxins A and B compromises the tight junctions of the epithelium cells involved in barrier function leading to the exposure of these toxins to circulatory antibodies via the immune elements of the lamina propria. In support of this, it has been shown recently that toxin A induces microtubule depolymerization which, along with actin disruption, may contribute to the loss of epithelial tight junction integrity (25).

Recent studies using toxin A and B knockout mutants have provided conflicting views on the roles of toxins A and B with respect to mediating disease in the hamster model for CDI. A study by Lyras et al. (21) suggests that toxin B is the primary virulence factor with respect to CDI, while a study by Kuehne et al. (16) suggests that both toxins play a role. The highly specific toxin-neutralizing antisera generated in the present study allowed an alternative approach to assessing the roles of these toxins using passive immunization studies. The data clearly show that, for CDI evoked by a C. difficile strain (VPI10463) capable of producing high levels of toxins A and B, neutralization of both toxins is essential for affording a degree of protection in the animal model.

An important consideration in the development of any antibody-based therapeutic approach for CDI is the demonstration of efficacy against a range of disease isolates. Recent studies have revealed the presence of more than 30 C. difficile toxinotypes which show considerable variability in the PaLoc region encoding for toxins A and B (31). Toxin B shows the highest level of diversity with, for example, toxinotype 0 and 3 toxins displaying ca. 13% variation within the immunodominant, C-terminal receptor-binding region. Studies on the botulinum neurotoxins reveal that this level of sequence variation can lead to significant differences in the binding affinities of antibodies to dominant epitopes and hence their toxin-neutralizing efficacy (37). In vitro toxin-neutralization studies showed that antibodies raised against toxinotype 0 toxin B adequately neutralized two other toxin B variants with undiminished neutralizing efficacy against toxinotype 3 toxin B and a 2-fold reduction against the toxinotype 5 toxin. In vivo, passive immunization studies were also conducted using ribotype 027 and 078 strains, which produce toxinotype 3 and 5 toxins, respectively, and high protective efficacy was demonstrated against both these strains. Both ribotypes 027 and 078 C. difficile belong to the “hypervirulent” clade which have the capacity to produce a functional binary toxin (7) and may have modified kinetics of toxin production in the gut (9). The present study suggests that, with respect to passive immunotherapy approaches, it is probably unnecessary to include a binary toxin-neutralizing antibody component in the drug substance. This finding is consistent with recent suggestions that the binary toxin, rather than causing extensive gut epithelial damage, may act as an additional colonization factor for C. difficile (36).

Studies were also conducted to assess the protective effects of passive immunization initiated after challenge with C. difficile spores. Because of the rapid onset of severe disease in the hamster model for CDI, the potential therapeutic window is relatively small and only allows for antibody treatment to be initiated up to 24 h postchallenge. Treatment regimens in which antibodies were administered 5 and 24 h after challenge were both protective relative to the nonimmunized controls. Initiation of treatment at 5 h postchallenge was most efficacious, which is not surprising since colonization and the initiation of toxin production are likely to occur within 12 to 24 h and the availability of a high level of neutralizing antibody during this period is likely to have the most beneficial effect.

Ovine antibodies provide a convenient platform for the manufacture of kilogram quantities of polyclonal antibodies at relatively low cost. They are currently used clinically for several indications, including digoxin toxicity (DigiFab) and snake envenomation (CroFab), and these products have excellent safety records (8, 28, 35). While human or humanized MAbs as immunotherapeutics have several advantages over animal-derived polyclonals as immunotherapeutic agents (long circulatory half-life, consistency of supply, and reduced humoral immune response), their high specificity and reliance on one, or a few, epitopes for efficacy may be a significant issue when targeting an antigen with known sequence diversity (18). With growing evidence of significant heterogeneity within the toxin A and B families (31), the use of single MAbs as therapeutic agents may represent a high-risk strategy for the long-term management of CDI. Ovine polyclonal antibodies are not without their drawbacks as potential therapeutic agents in that they have a shorter circulatory half-life than MAbs and cannot be administered repeatedly over the longer term due to host immune responses. However, their multivalent, diverse binding properties make them particularly effective at toxin-neutralization and less susceptible to antigenic variation. In the context of the management of CDI, ovine polyclonals are potentially useful for the treatment of severe, fulminant disease where the rapid neutralization of the gut toxins is likely to improve significantly disease outcome.

In summary, the use of ovine antibodies as a platform for the development of immunotherapeutics for the treatment of CDI is described here. Antisera with high toxin-neutralizing titers to toxins A and B were generated and shown to prevent infection from key epidemic C. difficile strains in passive immunization studies. As such, ovine antibodies may have a role in the management of severe CDI. Current research is focused on defining suitable recombinant antigens to underpin the large-scale manufacture of antibody reagents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Health Protection Agency, the NIHR Centre for Health Protection Research, and the Welsh Development Agency (Smart Award).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Ananthakrishnan AN. 2011. Clostridium difficile infection: epidemiology, risk factors and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8:17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babcock GJ, et al. 2006. Human monoclonal antibodies directed against toxins A and B prevent Clostridium difficile-induced mortality in hamsters. Infect. Immun. 74:6339–6347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartlett JG. 2006. Narrative review: the new epidemic of Clostridium difficile-associated enteric disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 145:758–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borriello SP. 1998. Pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41(Suppl C):13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braun V, Hundsberger T, Leukel P, Sauerborn M, von Eichel-Streiber C. 1996. Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene 181:29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brazier JS. 2008. Clostridium difficile: from obscurity to superbug. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 65:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kuehne SA, Cockayne A, Minton NP. 2010. The emergence of “hypervirulence” in Clostridium difficile. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300:387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dart RC, McNally J. 2001. Efficacy, safety, and use of snake antivenoms in the United States. Ann. Emerg. Med. 37:181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freeman J, Baines SD, Saxton K, Wilcox MH. 2007. Effect of metronidazole on growth and toxin production by epidemic Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes 001 and 027 in a human gut model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gerding DN, Johnson S. 2010. Management of Clostridium difficile infection: thinking inside and outside the box. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:1306–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giannasca PJ, et al. 1999. Serum antitoxin antibodies mediate systemic and mucosal protection from Clostridium difficile disease in hamsters. Infect. Immun. 67:527–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hussack G, et al. 2011. Neutralization of Clostridium difficile toxin A with single-domain antibodies targeting the cell receptor binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 286:8961–8976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jank T, Aktories K. 2008. Structure and mode of action of clostridial glucosylating toxins: the ABCD model. Trends Microbiol. 16:222–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kink JA, Williams JA. 1998. Antibodies to recombinant Clostridium difficile toxins A and B are an effective treatment and prevent relapse of C. difficile-associated disease in a hamster model of infection. Infect. Immun. 66:2018–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirby JM, et al. 2009. Cwp84, a surface-associated cysteine protease, plays a role in the maturation of the surface layer of Clostridium difficile. J. Biol. Chem. 284:34666–34673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuehne SA, et al. 2010. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature 467:711–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Libby JM, Wilkins TD. 1982. Production of antitoxins to two toxins of Clostridium difficile and immunological comparison of the toxins by cross-neutralization studies. Infect. Immun. 35:374–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lipman NS, Jackson LR, Trudel LJ, Weis-Garcia F. 2005. Monoclonal versus polyclonal antibodies: distinguishing characteristics, applications, and information resources. ILAR J. 46:258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lowy I, et al. 2010. Treatment with monoclonal antibodies against Clostridium difficile toxins. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lyerly DM, Bostwick EF, Binion SB, Wilkins TD. 1991. Passive immunization of hamsters against disease caused by Clostridium difficile by use of bovine immunoglobulin G concentrate. Infect. Immun. 59:2215–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyras D, et al. 2009. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature 458:1176–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McDonald LC, et al. 2005. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N. Engl. J. Med. 353:2433–2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitty RD, LaMont JT. 1994. Clostridium difficile diarrhea: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and treatment. Gastroenterologist 2:61–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Musher DM, et al. 2005. Relatively poor outcome after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis with metronidazole. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1586–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nam HJ, et al. 2010. Clostridium difficile toxin A decreases acetylation of tubulin, leading to microtubule depolymerization through activation of histone deacetylase 6, and this mediates acute inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 285:32888–32896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Navaneethan U. 2008. Clostridium difficile colitis: a silent epidemic in the United States. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 54:451–453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Brien JA, Lahue BJ, Caro JJ, Davidson DM. 2007. The emerging infectious challenge of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in Massachusetts hospitals: clinical and economic consequences. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 28:1219–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pizon AF, Riley BD, LoVecchio F, Gill R. 2007. Safety and efficacy of Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab in pediatric crotaline envenomations. Acad. Emerg. Med. 14:373–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roberts AK, Shone CC. 2001. Modification of surface histidine residues abolishes the cytotoxic activity of Clostridium difficile toxin A. Toxicon 39:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothman SW, et al. 1988. Immunochemical and structural similarities in toxin A and toxin B of Clostridium difficile shown by binding to monoclonal antibodies. Toxicon 26:583–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rupnik M. 2008. Heterogeneity of large clostridial toxins: importance of Clostridium difficile toxinotypes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:541–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rupnik M, Avesani V, Janc M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Delmée M. 1998. A novel toxinotyping scheme and correlation of toxinotypes with serogroups of Clostridium difficile isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2240–2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sambol SP, Tang JK, Merrigan MM, Johnson S, Gerding DN. 2001. Colonization for the prevention of Clostridium difficile disease in hamsters. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1760–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. 2003. Colonic pseudo-obstruction: the dilated colon in the ICU. Semin. Gastrointest. Dis. 14:20–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schaeffer TH, et al. 2010. Treatment of chronically digoxin-poisoned patients with a newer digoxin immune Fab: a retrospective study. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 110:587–592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwan C, et al. 2009. Clostridium difficile toxin CDT induces formation of microtubule-based protrusions and increases adherence of bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shone CC, et al. 2009. Bivalent recombinant vaccine for botulinum neurotoxin types A and B based on a polypeptide comprising their effector and translocation domains that is protective against the predominant A and B subtypes. Infect. Immun. 77:2795–2801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sougioultzis S, et al. 2005. Clostridium difficile toxoid vaccine in recurrent C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Gastroenterology 128:764–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stabler RA, et al. 2010. Comparative genome and phenotypic analysis of Clostridium difficile 027 strains provides insight into the evolution of a hypervirulent bacterium. Genome Biol. 10:R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Dissel JT, et al. 2005. Bovine antibody-enriched whey to aid in the prevention of a relapse of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: preclinical and preliminary clinical data. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ward SJ, Douce G, Dougan G, Wren BW. 1999. Local and systemic neutralizing antibody responses induced by intranasal immunization with the nontoxic binding domain of toxin A from Clostridium difficile. Infect. Immun. 67:5124–5132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Weiss K. 2009. Toxin-binding treatment for Clostridium difficile: a review including reports of studies with tolevamer. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 33:4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]