Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis is a member of the mammalian gastrointestinal microflora that has become a leading cause of nosocomial infections over the past several decades. E. faecalis must be able to adapt its physiology based on its surroundings in order to thrive in a mammalian host as both a commensal and a pathogen. We employed recombinase-based in vivo expression technology (RIVET) to identify promoters on the E. faecalis OG1RF chromosome that were specifically activated during the course of infection in a rabbit subdermal abscess model. The RIVET screen identified 249 putative in vivo-activated loci, over one-third of which are predicted to generate antisense transcripts. Three predicted antisense transcripts were detected in in vitro- and in vivo-grown cells, providing the first evidence of in vivo-expressed antisense RNAs in E. faecalis. Deletions in the in vivo-activated genes that encode glutamate 5-kinase (proB [EF0038]), the transcriptional regulator EbrA (ebrA [EF1809]), and the membrane metalloprotease Eep (eep [EF2380]) did not hinder biofilm formation in in vitro assays. In a rabbit model of endocarditis, the ΔebrA strain was fully virulent, the ΔproB strain was slightly attenuated, and the Δeep strain was severely attenuated. The Δeep virulence defect could be complemented by the expression of the wild-type gene in trans. Microscopic analysis of early Δeep biofilms revealed an abundance of small cellular aggregates that were not observed in wild-type biofilms. This work illustrates the use of a RIVET screen to provide information about the temporal activation of genes during infection, resulting in the identification and confirmation of a new virulence determinant in an important pathogen.

INTRODUCTION

Enterococci are both innocuous inhabitants of the human gastrointestinal tract and a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections. Enterococcus faecalis is responsible for the majority of enterococcal infections (38, 46), and the treatment or prevention of these infections can be complicated by the species' intrinsic and acquired mechanisms of resistance to numerous antibiotics as well as its ability to persist under harsh environmental conditions for extended periods of time (23). E. faecalis causes a wide variety of infections, including endocarditis, surgical-site infection, bacteremia, urinary tract infection, and endodontic infection (24). Previously reported in vitro studies provided evidence that many E. faecalis virulence genes are differentially expressed when grown in blood, serum, and urine (27, 53, 64), demonstrating that gene expression profiles change based on the microenvironment in which the organism is located. This characteristic is likely a key factor contributing to the pathogenesis of E. faecalis infections.

In order to thrive as a pathogen, E. faecalis must be able to colonize the site of infection, adapt to changes in nutrient availability, and evade phagocytes and other innate immune system defenses. Biofilm formation is a strategy frequently employed by pathogenic microbes to circumvent challenges posed by host environments, so it is not surprising that many E. faecalis infections have a biofilm etiology (37). Our laboratory previously used a two-pronged genetic approach involving transposon mutagenesis (31) and recombinase-based in vivo expression technology (RIVET) (4) to identify determinants of biofilm formation in the genome of E. faecalis OG1RF. This well-characterized laboratory strain lacks plasmids and many other mobile genetic elements that are typically present in clinical isolates such as V583 (7, 44), but it is still capable of forming biofilms and producing robust infections in experimental animals (7, 30). The conserved genetic determinants identified in this strain are likely part of the core genome shared by all E. faecalis strains and may be attractive targets for the development of vaccines or chemotherapeutic agents. Our previous screens revealed several dozen genes, many of which were not previously associated with biofilm development, that support E. faecalis biofilm growth under in vitro conditions. However, the extent to which these and most other biofilm-associated genes are used by E. faecalis during in vivo growth is unknown.

A number of methods have been used to study bacterial gene expression in vivo. Numerous in vivo microarray experiments, which assess bacterial transcription on a global scale, have been reported (26, 32, 41, 58, 61, 63, 66). Genetic techniques that facilitate genome-wide screening for specific in vivo-expressed genes include signature-tagged mutagenesis, which results in the identification of virulence genes among libraries of uniquely tagged transposon mutants, and in vivo expression technology (IVET), which is a promoter-trapping strategy that identifies promoters activated during infection (15). RIVET is a variation of IVET that uses transcriptional fusions to drive the expression of a promoterless DNA recombinase, which mediates an irreversible and heritable recombination event that can be detected in screens or selections (10). RIVET has been used with a diverse range of pathogens, including Vibrio cholerae (11, 43), Helicobacter pylori (12), and Staphylococcus aureus (33), and offers the benefit of being able to identify transiently expressed in vivo-induced genes that exhibit various levels of transcription (56).

In order to understand the genetic mechanisms that enable E. faecalis to establish infection and persist within a host, we used RIVET to investigate gene activation during the onset of infection in a rabbit subdermal abscess model. The RIVET screen identified a large number of putative in vivo-activated promoters oriented in both the sense and antisense directions, suggesting a genome-wide upregulation of transcription during growth in a mammalian environment. Transcripts from three of the putative antisense promoters were experimentally confirmed in vivo. Three sense-orientation, in vivo-activated genes that were also identified by our previously reported RIVET screen for biofilm-activated genes (4) were characterized for biofilm formation using in vitro assays and a rabbit model of experimental endocarditis. Notably, we found that the membrane metalloprotease Eep has an aberrant cell distribution phenotype during early biofilm formation and is required for E. faecalis endocarditis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and chemicals.

E. faecalis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. faecalis was routinely grown aerobically in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (BD Bacto, Becton, Dickinson, and Company, Sparks, MD) or Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; BD Bacto) under static conditions, or on BHI agar, at 37°C. Cultures for animal experiments were grown in trypsinized beef heart dialysate (BH) medium (48) under static conditions at 37°C for OG1RF subdermal chamber inocula; at 30°C, except as noted below, for OG1RF RIVET strain subdermal chamber inocula (4); and at 37°C with 7% CO2 for endocarditis inocula.

Table 1.

Enterococcus faecalis strains and oligonucleotides used in this study

| Strain or oligonucleotide | Description or sequence | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| OG1RF | Wild-type strain | 21 |

| OG1RF ΔproB | Markerless in-frame deletion of locus EF0038 | This study |

| OG1RF ΔebrA | Markerless in-frame deletion of locus EF1809 | 4; K. S. Ballering and G. M. Dunny, unpublished data |

| OG1RF Δeep | Markerless in-frame deletion of locus EF2380; also called JRC106 | 29 |

| OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) | Complementation plasmid; eep ORF with RBS cloned under expression of nisin-inducible promotera | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| NotI+0038F | 5′-CCCCGCGGCCGCCAAACTTACTCTAGCACGACGATC | This study |

| NcoI+0038R | 5′-CCCCCCATGGTTCAGAATGTTTTGTATTGTAGCGATT | This study |

| 0038-2stepF | 5′-AGAAACGAGGCACTTATGAGAAACAGTGACTGATTTAAAGCAACTAGGGC | This study |

| 0038-2stepR | 5′-GCCCTAGTTGCTTTAAATCAGTCACTGTTTCTCATAAGTGCCTCGTTTCT | This study |

| EF2380 XhoI F | 5′-CTAGTCTCGAGTTAAAAGAAAAAGCGTTGAATATCG | This study |

| EF2380 SpeI R RBS | 5′-CTAGTACTAGTGAATGAAGGAAGAAGGACATCTATG | This study |

| RIVET forward | 5′-AGCGTCGACTCTAGAGATCCAG | 4 |

| RIVET reverse | 5′-TACCCGTGCGTAACCAAAAAGTCG | 4 |

| EF0223F | 5′-TCACCGACAACAACTAAAGCT | This study |

| EF0223R | 5′-CATTTGGAATTAGAAGACCGC | This study |

| EF0909F | 5′-TAAGTTTTTCTTGGTTGGTATAAG | This study |

| EF0909R | 5′-ATCTTTTTCATGATTATCACTTTG | This study |

| EF2398F | 5′-GTTACCTTCGATGAAAGCGTC | This study |

| EF2398R | 5′-TCCTGATGAGATCGATGTTGT | This study |

See reference 8.

Lysozyme, mutanolysin, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), nisin, and all antibiotics were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions of 5FU at 50 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were prepared immediately before use. Stock solutions of other drugs were prepared as follows and stored at −20°C: nisin at 25 μg/ml in water, erythromycin at 50 mg/ml in methanol, chloramphenicol at 20 mg/ml in methanol, and kanamycin at 100 mg/ml in water. All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Pfu Ultra II Fusion DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used for all PCRs performed for strain and plasmid construction. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and are listed in Table 1.

Strain and plasmid construction.

The OG1RF ΔproB (locus EF0038) strain was constructed by using a previously described allelic exchange method (29). The deletion construct used for allelic exchange was generated with overlap-extension PCR by first amplifying two ∼1-kb fragments from OG1RF genomic DNA with primer pairs 0038-2stepR and NotI+0038F and NcoI+0038R and 0038-2stepF. The two products were annealed together, and second-step amplification was performed with primers NotI+0038F and NcoI+0038R. The resulting product was digested with NotI and NcoI, ligated into pCJK47 (29) predigested with the same enzymes, and propagated in Escherichia coli EC1000 cells grown on BHI medium with 100 μg/ml erythromycin. The deletion of proB had no effect on growth (data not shown).

Plasmid pMSP3535-eep was constructed by PCR amplification of the eep (locus EF2380) open reading frame (ORF) from OG1RF genomic DNA with primers EF2380 XhoI F and EF2380 SpeI R RBS. The resulting product was digested with XhoI and SpeI, ligated into pMSP3535 (8) predigested with the same enzymes, and propagated in E. coli DH5α or E. faecalis OG1RF Δeep cells grown on BHI medium with 75 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml erythromycin, respectively. There were no differences in the growth rates of OG1RF, the OG1RF Δeep strain, or the OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) strain (data not shown).

Rabbit models of subdermal abscess infection and endocarditis.

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines set forth by the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol used in this work (approval number 0910A73332). Animals were euthanized with Beuthanasia-D, and efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Subdermal chambers were implanted into the flanks of New Zealand White rabbits (male or female, 2 to 3 kg) essentially as previously described (50, 60). Briefly, hollow perforated polyethylene golf balls were obtained from a sporting goods store and were sterilized by boiling in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min. After cooling, a single chamber was aseptically placed through an incision into a surgically created subcutaneous pocket in each anesthetized rabbit. Incisions were sutured closed, and animals were allowed to heal for at least 6 weeks before infection, during which time the chambers became encapsulated with fibrous tissue and filled with approximately 30 ml of serous fluid. Samples for RIVET analysis were obtained from two rabbits in which chambers had been implanted 10 and 28 weeks prior to infection. To initiate infection, 2 ml of serous fluid was aspirated from the subdermal chamber and was replaced with 2 ml of inoculum prepared as described below.

Endocarditis infections were carried out as previously described (16). Briefly, single colonies of each strain were inoculated into BH medium and grown overnight. Cultures of the OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) strain also contained 10 μg/ml erythromycin and 25 ng/ml nisin. Cells were pelleted and resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 in potassium phosphate-buffered saline (KPBS), corresponding to approximately 2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU/ml. Following surgery, 2 ml was administered intravenously via the marginal ear vein to initiate infection. Rabbits were euthanized after 4 days, at which point the hearts were removed and dissected to expose the aortic valve. Vegetations—the classic lesions associated with infectious endocarditis—and valve leaflets were harvested, weighed, homogenized in 1 ml of THB, serially diluted, and plated onto BHI agar to quantify bacteria. Homogenates from animals infected with the OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) strain were also plated onto BHI agar containing 10 μg/ml erythromycin to determine the percentage of cells that retained the complementation vector for the duration of the infection.

Endocarditis results were analyzed for statistical significance with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with χ2 approximation using JMP software (version 8.0.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RIVET screen in subdermal abscess infection.

The E. faecalis RIVET system, including the genomic library used in this study, was described previously (4). Aliquots of the library were grown for 5.5 to 6.5 h in 10 ml BH medium containing 2,000 μg/ml kanamycin and 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol (BHkan2000cm10) and then diluted 1:20 into 10 to 25 ml of BHkan2000cm10 and further incubated for 14 to 15.5 h. The cultures were diluted 1:5 into 50 ml BHkan2000cm10 (rabbit A) or 100 ml BH medium without antibiotics (rabbit B) and incubated for 3 h at 30°C (rabbit A) or 2 h at 37°C (rabbit B). Bacteria were centrifuged for 15 min at 4,000 × g at 4°C and resuspended in KPBS to densities of ∼1 × 107 CFU/ml for rabbit A and ∼4 × 109 CFU/ml for rabbit B. Two-milliliter volumes were used for subdermal chamber infections. Approximately 1.5-ml aspirates were collected at 2, 4, 8, 24, and 96 h postinoculation from the chamber in rabbit A. For rabbit B, 4-ml aspirates were collected from the chamber at 2, 4, and 8 h postinoculation. Rabbit B was euthanized at 24 h and the chamber was retrieved. The explanted chamber was bisected, and the interior surfaces were scraped several times with a sterile rubber policeman that was repeatedly rinsed in a tube containing 25 ml KPBS. Six tissue sections that appeared to contain white abscesses formed at the sites of chamber perforations were harvested, rinsed with 1 ml KPBS, and homogenized in 2 ml KPBS. Aliquots of the initial inocula and all collected samples were plated onto BHI agar with and without 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol to determine the bacterial load and to assess whether the RIVET library plasmid was lost from cells during infection due to the lack of antibiotic selection in chambers. Cell counts indicated that the plasmid was lost at a low, but variable, frequency starting at 4 to 8 h postinoculation (data not shown). Bacterial counts reported in Fig. 1 are from chloramphenicol plates, in order to represent the number of cells containing the RIVET plasmid at each time point assayed.

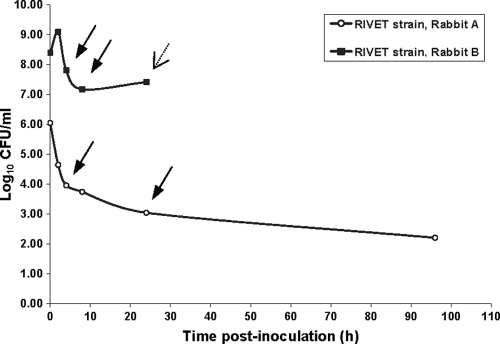

Fig 1.

Recovery of the E. faecalis RIVET strain from subdermal abscesses. Two milliliters of the E. faecalis OG1RF RIVET library was inoculated into subdermal chambers from which 2 ml of serous fluid was withdrawn. Dilutions of fluid aspirated from implanted chambers at the indicated time points following inoculation were plated to determine the number of viable E. faecalis CFU recovered. Results are reported as log10 CFU/ml. The 0-h time points were calculated by dividing the total CFU in the 2-ml inocula by 30 ml, the volume of serous fluid in the implanted chamber. Arrows indicate the time points analyzed by RIVET: 4, 8, and 24 h postinoculation. Infection of rabbit A was carried out for 96 h, whereas infection of rabbit B was terminated at 24 h, at which time the chamber was explanted and samples were harvested from the chamber surface and surrounding tissues (open-head arrow).

Analysis of RIVET clones for in vivo-activated promoters.

RIVET clones that underwent a chromosomal excision event were selected by plating on BHI agar containing 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 130 μg/ml 5FU. Individual colonies were patched onto BHI agar containing 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 130 μg/ml 5FU, and 1,000 μg/ml kanamycin. All chloramphenicol- and 5FU-resistant, kanamycin-sensitive colonies were grown overnight in 5 to 10 ml BHI medium with 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol and treated with 30 mg/ml lysozyme in 0.4 ml TE (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA) for 30 to 45 min at 37°C. RIVET plasmids were harvested from lysozyme-treated cells with the QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Plasmid inserts were sequenced at the University of Minnesota BioMedical Genomics Center DNA Sequencing and Analysis Facility with primers RIVET forward and RIVET reverse (4). Sequences were aligned by using Sequencher software (version 4.9 or earlier; Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI) and then BLASTed against the E. faecalis V583 genome at the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) Comprehensive Microbial Resource to identify the ORF downstream of the putative promoter. When the RIVET insert spanned more than one ORF, particularly when adjacent ORFs were separated by a sizable intergenic region, the putative in vivo-activated promoter was assigned to the furthest downstream ORF. In contrast, when two or more ORFs were directly adjacent or overlapping, thus appearing that they are likely to be cotranscribed, the putative promoter was assigned to the first ORF in the group. Sequences containing OG1RF-specific regions were initially compared to the NCBI GenBank E. faecalis OG1RF genome (accession number ABPI00000000.1) (7), but because the annotation of that sequence remained incomplete until recently (updated in 2011 with accession number CP002621), ORF identifications were obtained by using an OG1RF annotation generated with the Rapid Annotation Using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server (3) (see Table S1 and supplemental materials and methods in the supplemental material).

Gene expression analysis of antisense transcripts in OG1RF from the subdermal abscess model.

Subdermal abscess infections with E. faecalis OG1RF were carried out with three rabbits, as described above. A single colony of E. faecalis OG1RF was inoculated into 10 to 25 ml of BH medium, incubated for approximately 15 h, diluted 1:5 into 25 to 50 ml of fresh BH medium, and incubated for two more hours. Bacteria were centrifuged for 15 to 20 min at 2,250 × g at 4°C. Pelleted cells were resuspended to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼1.3 to 1.6 in KPBS, and 2 ml was used for each subdermal chamber infection. Approximately 2 ml of the initial inoculum and chamber aspirates harvested at 4 h postinoculation were immediately added to 4 ml of RNAprotect Bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Inc.), processed according to the manufacturer's instructions, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Frozen aspirates were thawed, resuspended in 0.4 ml of RNase-free TE containing 50 mg/ml lysozyme and 1,000 U/ml mutanolysin, homogenized with a hand-held motorized pestle, and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Each sample was then split in half and extracted in duplicate with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with an added QIAshredder (Qiagen, Inc.) homogenization step immediately after the addition of buffer RLT. RNA was eluted from each column with two 30-μl volumes of RNase-free water, and total RNAs from duplicate extractions of each sample were pooled together. Contaminating DNA was removed by using a Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the rigorous protocol provided by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized with gene-specific primers using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Invitrogen Corp.). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out with an iQ5 iCycler real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) with iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and threshold cycle (CT) values were averaged. EF0886, which was identified by microarray analysis as being a gene with nonchanging expression at the analyzed time points (K. L. Frank and G. M. Dunny, unpublished data), was used as a reference gene. The fold change for each sample was calculated according to a method described previously by Pfaffl (45), and the three biological replicates were averaged together to obtain the reported fold change.

Biofilm microscopy.

E. faecalis biofilms were grown on 11-mm-diameter Aclar fluoropolymer coupons (Aclar embedding film, 7.8-mil thickness; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in tryptic soy broth without added dextrose (TSB−dex; Becton, Dickinson, and Company) under gentle agitation (150 rpm) for 6 h. After washing three times with PBS, the cell envelope was labeled by using a red fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate (Invitrogen), and the coupons were mounted in Vectashield HardSet medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired with a Cascade 1k electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) as wide-field z stacks with a 20× 0.75-numerical-aperture (NA) or a 60× 1.4-NA objective (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Images of z stacks were taken at 0.4- or 0.15-μm intervals (20× and 60×, respectively) and deconvolved using Huygens Professional software (version 3.7.1; Scientific Volume Imaging, Netherlands). The presented images are maximum intensity projections determined by using ImageJ (version 1.5k; NIH, Bethesda, MD) and are representative of at least three biological and four technical replicates per sample. The COMSTAT2 software package was used to quantify biofilm biomass (28).

RESULTS

RIVET screen to identify promoters activated during subdermal abscess infection.

To explore E. faecalis gene activation in vivo, we used a subdermal chamber infection model that is amenable to time course sampling for the study of gene expression using genetic analysis or transcription profiling (67). This model consists of a subcutaneously implanted, hollow chamber with a perforated surface that becomes encapsulated after insertion, fills with a serous fluid containing immune cells, and mimics the environment of a localized abscess upon the introduction of bacteria (52, 60). E. faecalis cells remain localized within the chamber fluid, which initially contains a stable population of leukocytes comprised of ∼10% polymorphonuclear cells and 90% mononuclear cells (60), while additional immune cells enter the chamber during the course of infection, thus exposing the bacteria to a changing host response.

Two independent RIVET screens were conducted with the same library used for our group's previous RIVET screen for in vitro biofilm formation genes (4). In this system, in vivo-activated promoters drive the expression of the gene for the site-specific recombinase TnpR. TnpR acts at its target sequences (res sites) to excise an engineered region of the chromosome in the RIVET strain that encodes genes for both kanamycin resistance and sensitivity to 5FU (upp); the latter serves as a counterselectable marker. Excision events result in a selectable and heritable change in genotype, as cells that have undergone resolution are rendered sensitive to kanamycin and resistant to 5FU (see Materials and Methods) (4). In order to eliminate promoters expressed constitutively or during growth in culture medium, the RIVET library inoculum was pregrown with high levels of kanamycin to select against in vitro resolution events.

The initial infection (rabbit A) (Fig. 1) represented the first use of our RIVET system in vivo. The RIVET library was inoculated at 6.0 log10 CFU/ml and was sampled at 2, 4, 8, 24, and 96 h postinoculation to assess survival. Bacterial counts dropped 2 logs during the first 4 h of infection, with a subsequent 1-log drop after 24 h. The strain persisted in the subdermal chamber for the duration of the 4-day infection. Clones were collected from chamber aspirates at 4 and 24 h postinoculation for screening, as we reasoned that these time points would allow sufficient time for cells to undergo resolution events following initial adaptation to the in vivo growth environment (4 h) and the activated host immune response (24 h). Dilutions of subdermal chamber fluid were plated onto counterselective medium containing 5FU to identify cells that underwent resolution. 5FU-resistant colonies were then tested for kanamycin sensitivity to confirm complete resolution.

Forty-six clones with the resolution phenotype were identified from 100 colonies screened from the 4-h aspirate. Only 38 clones with the correct phenotype were obtained after screening 1,550 colonies from the 24-h aspirate. The genomic DNA inserts from the 84 resolved clones were sequenced. The low rate of recovery of clones with the desired phenotype at 24 h (2.5%, compared to 46% at 4 h) suggested that selective pressures in the subdermal chamber environment caused genetic changes that resulted in high levels of background growth on the counterselection medium. For the subsequent infection (rabbit B), we focused on the 4- and 8-h time points rather than the 24-h time point.

A higher inoculum of ∼8.5 log10 CFU/ml was used for the second infection (rabbit B) (Fig. 1). In contrast to RIVET rabbit A, the bacterial counts in RIVET rabbit B increased slightly at 2 h before dropping almost 2 logs to a low point at 8 h. Cell counts increased slightly by 24 h, at which time the experiment was terminated and the subdermal chamber was explanted in order to sample biofilm-associated E. faecalis cells from the inner surface of the chamber. The inside of the tissue capsule from which the chamber was excised contained several small white pockets resembling abscesses at the regions corresponding to the perforations in the subdermal chamber; six of these tissue sections were also harvested, homogenized, and screened for resolved clones. Approximately 14% of colonies screened from the 4- and 8-h aspirates had the desired phenotype. In total, 133 clones from the 4-h aspirate, 163 clones from the 8-h aspirate, 57 clones from the chamber surface, and 99 clones from the tissues were found to have the correct phenotype and were sequenced for the second subdermal RIVET infection.

The combined sequencing of 536 clones from the two rabbits resulted in the identification of 249 unique upregulated loci from 260 nonsibling clones (see Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). Forty-one of the unique upregulated loci were identified in rabbit A clones; 24.4% (10/41) of those loci were also identified among rabbit B clones. Eleven loci were identified by two unique clones spanning the same genomic region. Many of the nonunique clones were siblings of clones identified at earlier time points. Some inserts contained two nonadjacent genomic sequences, which are thought to represent library cloning artifacts, while a few sequenced plasmids contained no genomic inserts and were thus false positives, which further suggested that selective pressures in the subdermal chambers caused some degree of genetic rearrangements or deletions in the RIVET plasmid. Clones in the two latter categories were disregarded in the final analysis.

The RIVET clones fit into one of four categories with respect to orientation. The majority of the loci (n = 114) were identified by clones that contained a genomic sequence that overlapped at least one ORF and the associated 5′-untranslated region, which was assumed to contain the putative in vivo-activated promoter, in the same orientation (i.e., sense direction) as that of the recombinase (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Forty-two loci were identified by sense-direction clones with genomic sequences that were located within an ORF, which indicates that internal promoters may be present (Table S2). The remaining 93 loci were identified from clones with genomic inserts whose directionality was oriented opposite that of the recombinase (i.e., antisense) (Table S3). Sixty-four of these loci overlapped one or more ORFs on the opposite DNA strand, whereas 29 were contained wholly within an ORF on the opposite DNA strand.

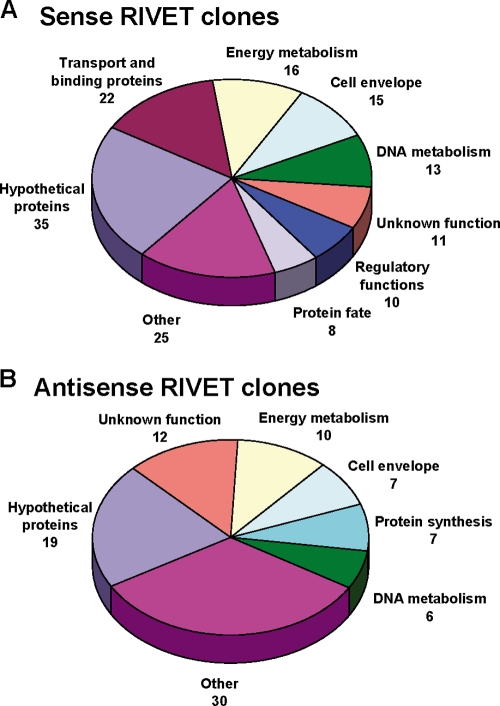

All but three of the identified loci contain protein-encoding ORFs; the other three loci encode large- and small-subunit rRNA genes. No clear patterns emerged among the protein-encoding loci when their predicted functions were considered by time point or source; therefore, RIVET clones were grouped according to their sense or antisense orientations in order to assess the distribution of functional categories represented among the putative in vivo-activated loci (Fig. 2). Approximately one-third of both the sense and antisense loci encode proteins with hypothetical or unknown functions. Many of the putatively activated genes identified in the RIVET screen have functions pertinent to cell growth and metabolism. Aside from the hypothetical proteins, transport and binding proteins comprised the largest functional category of sense clones (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the same category was underrepresented among the antisense clones (Fig. 2B); conversely, more antisense than sense clones were present in the protein synthesis category.

Fig 2.

Distribution of E. faecalis OG1RF sense (A) and antisense (B) RIVET clones isolated from a subdermal abscess infection. The E. faecalis genomic DNA sequence from each isolated RIVET clone was analyzed as described in Materials and Methods to determine the identity of the putative in vivo-activated promoter and the corresponding gene immediately downstream of the putative promoter. Each corresponding gene was assigned to a functional category by using the JCVI Comprehensive Microbial Resource (http://cmr.jcvi.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/CmrHomePage.cgi) for the E. faecalis V583 genome. All protein-encoding loci, as listed in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material, were included. The number of genes in each functional category is given. The functional categories classified as “other” in panel A are as follows: cellular processes (5 genes); fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism (4 genes); pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides (4 genes); protein synthesis (4 genes); amino acid biosynthesis (2 genes); signal transduction (2 genes); transcription (2 genes); biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers (1 gene); and mobile and extrachromosomal element functions (1 gene). The functional categories classified as “other” in panel B are as follows: biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers (5 genes); pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides (5 genes); regulatory functions (5 genes); signal transduction (4 genes); cellular processes (3 genes); transport and binding proteins (3 genes); central intermediary metabolism (2 genes); fatty acid and phospholipid metabolism (1 gene); protein fate (1 gene); and transcription (1 gene).

Identification of antisense RNAs expressed during mammalian infection.

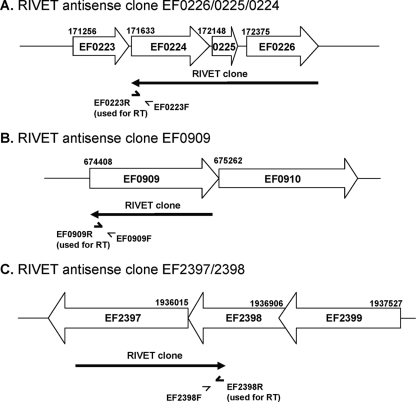

Since more than one-third of the RIVET clones isolated were in an antisense orientation, we performed reverse transcription with gene-specific primers for selected putative antisense transcripts using RNA from OG1RF cells harvested from subdermal chamber inocula and from subdermal chamber aspirates at 4 h postinfection. We looked for the expressions of three antisense transcripts represented by RIVET antisense clones EF0226/0225/0224, EF0909, and EF2397/2398 (Fig. 3). These antisense RIVET clones were chosen from among more than 20 unique RIVET clones that each correlated with a cognate sense-strand gene that was found by microarray analysis to be significantly downregulated at 8 h in the subdermal abscess model (Frank and Dunny, unpublished).

Fig 3.

Orientation of antisense RIVET clones and location of detected antisense transcripts. (A) RIVET antisense clone EF0226/0225/0224. (B) RIVET antisense clone EF0909. (C) RIVET antisense clone EF2397/2398. The genomic orientations of three antisense RIVET clones (black arrows) that predicted the presence of antisense transcripts are shown. The relative locations of primers used to subsequently detect and quantify the antisense transcripts by quantitative RT-PCR are indicated by heavy (reverse primers, used for reverse transcription and amplification) and light (forward primers, used for amplification) half-arrows. The nucleotide start site of each ORF, as annotated in Table S1 in the supplemental material, is indicated at its 5′ end. Although the graphic is not drawn to scale, the arrows representing adjacent genes within a locus are proportional to one another.

We succeeded in amplifying all three transcripts from OG1RF cells grown in vitro and in vivo, whereas no signal was detected in any of the no-reverse-transcriptase controls (data not shown). Quantitative RT-PCR of the in vivo-expressed antisense RNAs revealed that the transcripts identified by antisense RIVET clones EF2397/2398 and EF0909 were upregulated at 4 h by 1.5-fold (standard deviation, 1.1) and 1.4-fold (standard deviation, 1.4), respectively (n = 3 each). This is consistent with the RIVET screen in that the EF2397/2398 and EF0909 antisense clones were identified at 4 h. The antisense RNA identified by antisense RIVET clone EF0226/0225/0224 was downregulated in vivo at 4 h by 1.7-fold (standard deviation, 0.6; n = 3). The EF0226/0225/0224 antisense RIVET clone was identified in tissue harvested from the subdermal abscess infection site at 24 h postinfection, suggesting that this transcript is transiently upregulated at some point during infection other than at 4 h or that it was expressed in a subpopulation of cells in the host; the same considerations may also be relevant to the relatively low levels of upregulation measured for the other two antisense transcripts. The primary significance of these results is that the existence of novel putative transcripts expressed in vivo, which were suggested by the RIVET screen, is supported by the RT-PCR experiments. This will allow for subsequent precise identification of the relevant antisense promoters, time course studies of antisense promoter expression, and functional studies of the effects of the antisense transcripts on the expression of mRNAs generated from the respective cognate sense strands.

Identification of in vivo-activated genes also associated with biofilm growth in vitro.

We compared the in vivo-activated sense genes from the subdermal abscess RIVET screen (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) with the genes identified in previous transposon and RIVET screens for determinants of biofilm formation (4, 31). In total, 28 genes from the subdermal abscess RIVET screen were identified in the biofilm formation genetic screens (Table 2). Only two of the putative in vivo-activated promoters overlapped with the in vitro biofilm mutants found in the transposon screen, while the other 26 genes overlapped with promoters isolated from in vitro biofilm RIVET clones. Five of the genes are functionally annotated as transporters, and four genes have roles in energy metabolism. Two transcriptional regulators were also upregulated in biofilms and in vivo.

Table 2.

E. faecalis OG1RF loci identified by an in vivo RIVET screen which were also identified by previously reported RIVETe or transposonf screens for in vitro biofilm formation

| Locus | Gene description | JCVI functional category | Time(s) postinoculation (h) or location of isolation of in vivo RIVET clonea | Time(s) of isolation of in vitro biofilm RIVET cloneb | Transposon insertion mutant defective in in vitro biofilm formationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF0038 | Glutamate 5-kinase | Amino acid biosynthesis | 4 | 5 days | |

| EF0059 | UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase | Cell envelope | 4 | 2 h, 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF0082 | Major facilitator family transporter | Transport and binding proteins | 4 | 2 h | |

| EF0246 | Amino acid ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | Transport and binding proteins | 4 | 2 h, 5 days | |

| EF0402 | Na+/H+ antiporter | Transport and binding proteins | 4 | 2 h | |

| EF0721 | ATP-dependent DNA helicase PcrA | DNA metabolism | 8 | + | |

| EF0722 | DNA ligase, NAD dependent | DNA metabolism | 24 | 5 days | |

| EF0798 | Hypothetical protein | Hypothetical proteins | 8 | 2 h, 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF1348 | Glucan 1,6-alpha-glucosidase, putative | Energy metabolism | 8 | 3 days | |

| EF1591 | Transcriptional regulator, AraC family | Regulatory functions | Tissue | 2 h, 3 days | |

| EF1755 | Phosphate ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | Transport and binding proteins | 4 | 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF1809 | Transcriptional regulator, GntR family | Regulatory functions | Tissue | 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF1826 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, zinc containing | Energy metabolism | 4 | 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF1918 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Hypothetical proteins | 4 | 2 h, 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF1962 | Triosephosphate isomerase | Energy metabolism | 4 | 5 days | |

| EF1978 | DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase | DNA metabolism | 4 | 2 h, 5 days | |

| EF2207 | DNA-binding protein, Fis family | Regulatory functions | 8 | 2 h, 5 days | |

| EF2380 | Membrane-associated zinc metalloprotease, putative | Protein fate | 8 | 5 days | |

| EF2570 | Aldehyde oxidoreductase, putative | Unknown function | 4, 24 | 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF2668 | Magnesium transporter | Transport and binding proteins | 8 | 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF2744 | Peptidase, M42 family | Protein fate | 8 | 2h, 3 days, 5 days | |

| EF2889 | 2-Hydroxy-3-oxopropionate reductase | Energy metabolism | 4 | 2 h | |

| EF3008 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Hypothetical proteins | Tissue | 5 days | |

| EF3056 | Sortase family protein | Cell envelope | 8 | + | |

| EF3124 | Polypeptide deformylase, authentic frameshift | Protein fate | Chamber surface | 5 days | |

| EF3177 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Hypothetical proteins | Tissue | 2h, 5 days | |

| EF3258 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Hypothetical proteins | 4 | 3 days, 5 days | |

| OG1RF0176 (EF2352)d | GTP-binding protein LepA | Unknown function | 4 | 2 h |

Indicates the sampling time or location from which the clone was isolated. Two nonsibling clones were isolated for EF2570 at the indicated time points. Tissue and chamber surface clones were isolated from a chamber explanted at 24 h postinoculation.

Indicates time points when clones were isolated from in vitro biofilms (4).

+ indicates that a transposon insertion mutant defective in in vitro biofilm formation was obtained in the locus (31).

Locus EF2352 is annotated as OG1RF0176 in E. faecalis OG1RF (7).

See reference 4.

See reference 31.

Role of in vivo-activated genes in endocarditis.

We hypothesized that genes found in both the in vivo and biofilm RIVET screens (Table 2) may be important for biofilm formation in the host. To evaluate this possibility, we tested strains with markerless in-frame deletions of three genes listed in Table 2—proB (EF0038), encoding glutamate 5-kinase; ebrA (EF1809), encoding a transcriptional regulator; and eep (EF2380), encoding a membrane metalloprotease—in a rabbit model of endocarditis, which is a biofilm infection of the endocardium, including the heart valves. The ebrA gene was chosen because an ΔebrA strain was previously shown to have a defect in the formation of biofilms on cellulose membranes (4). The proB gene was selected due to studies examining the contribution of proline to the survival and pathogenicity of other Gram-positive bacteria in select animal models (5, 51, 57). The eep locus was of particular interest because of its previously characterized function in the processing of peptide pheromone signals for conjugative plasmids (2, 13). The roles of the proB and eep loci in biofilm formation have not been studied previously for E. faecalis.

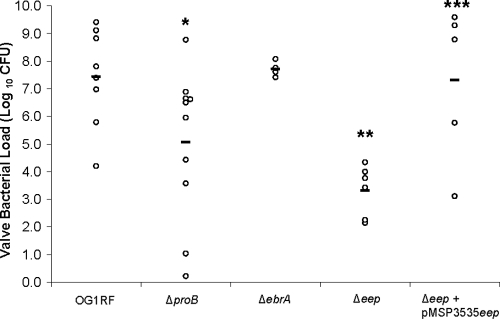

OG1RF infected injured aortic valves with a mean valve bacterial load of 7.4 log10 CFU (Fig. 4) and produced large vegetations (Table 3). Compared to OG1RF, the ΔebrA strain was not impaired in either valve colonization or vegetation formation (Fig. 4 and Table 3), whereas the ΔproB strain exhibited a 2.3-log10 decrease in the valve bacterial load, which was statistically significant (Fig. 4). The Δeep strain was severely attenuated in causing endocarditis, as evidenced by the 4-log10 decrease in numbers of CFU recovered from the heart valves of Δeep strain-infected rabbits (Fig. 4). The significant defect was also readily apparent in the small vegetations observed for the mutant strain (Table 3).

Fig 4.

Role of in vivo-activated, biofilm growth-associated genes in endocarditis virulence. A total of 109 CFU of each E. faecalis strain was intravenously injected into New Zealand White rabbits following the induction of aortic valve damage, as described in Materials and Methods. Vegetations and heart valve leaflets were harvested at 4 days postinoculation. The log10 valve bacterial load is shown for wild-type strain OG1RF (n = 8), the OG1RF ΔproB strain (n = 10), the OG1RF ΔebrA strain (n = 4), the OG1RF Δeep strain (n = 6), and the OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) strain (n = 5). Horizontal bars denote the arithmetic means of the log10-transformed values. ∗, P = 0.0367 for OG1RF versus the ΔproB strain; ∗∗, P = 0.003 for OG1RF versus the Δeep strain; ∗∗∗, P = 0.0446 for the Δeep strain versus the Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) strain.

Table 3.

Weights of endocarditis vegetations produced by E. faecalis strains after 4 days of infection

| Strain | No. of vegetations | Mean vegetation wt (mg) | SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OG1RF | 8 | 47.6 | 29 | |

| ΔproB | 10 | 24.0 | 27.7 | 0.33a |

| ΔebrA | 4 | 42.5 | 20.6 | 0.8651a |

| Δeep | 6 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 0.0065a |

| OG1RF Δeep(pMSP3535-eep) | 5 | 32.1 | 35.3 | 0.027b |

Compared to OG1RF.

Compared to the Δeep strain

Complementation of the Δeep strain rescues the endocarditis attenuation phenotype.

Upon observing the striking attenuation of the Δeep strain in the endocarditis model, we wondered whether the defect could be complemented by the expression of the wild-type eep locus in trans. As shown in Fig. 4, the Δeep endocarditis defect was fully rescued when the locus was expressed under the control of a nisin-inducible promoter on a plasmid. The mean weight (± standard deviation) of vegetations formed by the complemented strain was 32.1 ± 35.3 mg (P value of 0.027 compared to the Δeep strain). Only 2% of the cells retained the complementation plasmid at the end of the experiment due to the lack of antibiotic selection to maintain the plasmid. In addition, cells were not exposed to the inducing agent during infection, so Eep levels would have been the most abundant at the time of inoculation. The RIVET clone encoding the promoter for the eep locus was isolated from the subdermal abscess model at 8 h postinoculation (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), meaning that the promoter was activated within the first several hours of infection. Taken together, these data suggest that the role of Eep in endocarditis occurs during the early stages of valve infection.

Characterization of in vitro biofilm formation by ΔproB, ΔebrA, and Δeep strains.

Biofilm formation by OG1RF and the ΔproB, ΔebrA, and Δeep strains was evaluated at the 4- and 24-h time points by using in vitro biofilm assays that examined the total biomass or recovery of viable cells. No defects in biofilm formation were detected among any of the strains at 4 or 24 h in the three assays (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

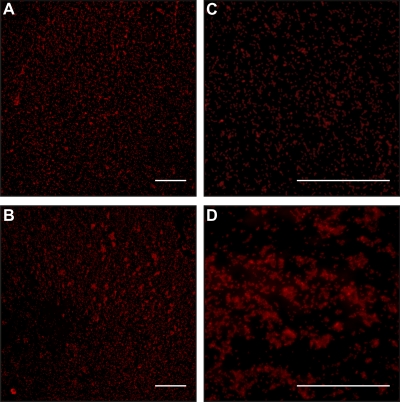

The significant endocarditis attenuation demonstrated by the Δeep strain led us to use immunofluorescence microscopy to further characterize biofilms formed by this strain. A striking morphological difference between the mutant and wild-type strains was observed for E. faecalis in vitro biofilms grown for 6 h (Fig. 5). By use of a lectin conjugate that localizes primarily to the bacterial cell envelope, the Δeep strain biofilms were found to be composed largely of small cellular aggregates; such structures were not observed in OG1RF biofilms at the same time point. This phenotypic difference could be seen even under a low magnification (×200) (Fig. 5A and B). Quantitative COMSTAT2 analysis of the biomass was consistent with the fluorescent micrographs (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). While the average biomass was only slightly elevated in the mutant strain (∼23% higher), the range of variation between samples was much greater for the Δeep strain biofilms.

Fig 5.

Fluorescent micrographs of OG1RF (A and C) and Δeep strain (B and D) biofilms at 6 h postinoculation. Biofilms were grown on Aclar fluoropolymer coupons in tryptic soy broth without added dextrose, washed, and stained with wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 as described in Materials and Methods. Representative images acquired at magnifications of ×200 (A and B) and ×600 (C and D) are shown. Scale bars, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections in hospitalized and immunocompromised individuals in recent years emphasizes the importance of elucidating the genetic basis of enterococcal pathogenicity. The expression of virulence factors in E. faecalis, whether encoded on mobile genetic elements in select strains or found in the chromosomes of all strains, is likely part of a larger physiological adaptation that E. faecalis cells undergo when occupying a niche as a pathogen. Here we report the results of a genome-level analysis using RIVET to identify genetic factors that are upregulated during the course of E. faecalis subdermal abscess infection. The use of the plasmid- and pathogenicity island-free E. faecalis strain OG1RF in this study allowed us to gain insights into gene expression from the E. faecalis core genome during the establishment of infection. In addition, by comparing the results of RIVET screens carried out with the subdermal abscess infection model and in in vitro biofilms (4), we were able to attribute functions for in vivo growth and virulence to two genes in E. faecalis that were not previously associated with the infection process (Fig. 4).

An advantage that RIVET methodology provides is the ability to detect heterogeneous gene expression among cells in sampled populations. We identified many in vivo-activated promoters with the RIVET screen (Fig. 2 and see Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material) across multiple time points in the subdermal infection model. Those genes that are transiently expressed or are highly expressed in only a minor subpopulation of the enterococci in the host would not have been detected with other types of gene expression techniques (e.g., microarray analysis). The RIVET screen also permitted the sampling of multiple locations in the model, including the inner surface of an explanted subdermal chamber. Only one in vivo-activated promoter from a surface-associated clone was found to overlap with biofilm growth-associated genes (Table 2), suggesting that many of the genes listed in Table 2 may be important for the adaptation of E. faecalis to alternate growth conditions besides biofilms.

We encountered difficulty in isolating resolved clones from the 24-h time point due to the high levels of background growth of unresolved clones on the counterselective agent 5FU. In E. coli and Bacillus subtilis, uracil uptake and transport are hindered by elevated levels of ppGpp associated with a stringent response (6, 40). We have observed by microarray analysis that OG1RF cells in the subdermal abscess model activate a stringent response by 8 h postinoculation (Frank and Dunny, unpublished). Thus, the apparent decrease in 5FU toxicity at 24 h postinoculation may be a result of the physiological state of the bacteria in the subdermal abscess environment.

Two other genome-wide screens for E. faecalis genes that contribute to growth and virulence in a host have been performed. A Cre recombinase-based RIVET method for a plasmid-free derivative of E. faecalis V583 was recently developed (27). Over 60 activated genes were collectively identified by this method in screens performed in mouse models of peritonitis and bacteremia. Two of the genes, EF0106 (carbamate kinase) and EF2987 (a conserved hypothetical protein), were found in our RIVET screen. Those authors also screened for in vivo-activated promoters in Galleria mellonella larvae; zero of the four in vivo-activated promoters identified were found in our RIVET screen. A different group evaluated 540 OG1RF Tn917 transposon insertion mutants for their abilities to kill the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (34). Twenty-three of the insertion mutants were attenuated in the killing of C. elegans, with five of the mutants also showing attenuation in a mouse model of peritonitis. None of these genes were found to be upregulated in our RIVET data sets. The complete lack of overlap in the data collected from the C. elegans and G. mellonella models with our data may be due to the use of nonmammalian hosts, suggesting that such models may not be ideal for the identification of genes involved in mammalian adaptation. The differences in strains, mammalian hosts, and infection models used in our study compared to those used in the mammalian Cre recombinase-based RIVET screens may have all contributed to the fact that there was little overlap observed between the two studies. Regardless, further investigation of the two overlapping in vivo-expressed genes is warranted, as their functions may be critical for E. faecalis adaptation in mammalian environments.

The prevalence of small regulatory RNAs, including antisense RNAs, in bacteria has recently become apparent (59). The expression of bacterial antisense RNAs during infection has been noted in studies that employed tiling arrays (61), IVET (54, 55), and RIVET (11, 42, 43, 56). Approximately 1,000 antisense transcripts have been identified in E. coli; many of the antisense transcripts initiated from a nucleotide located within the open reading frame encoded on the sense strand (20). Five antisense RIVET clones were isolated in our previously reported in vitro biofilm RIVET screen (4), and antisense clones were apparently found in the E. faecalis Cre recombinase-based RIVET screen, although those authors did not report any information about the identities of the putative antisense promoters (27). Over one-third of the RIVET clones in this study had genomic DNA inserts oriented upstream of the recombinase such that expression from the putative promoters would result in the production of antisense transcripts (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). While it seems unlikely that all of these clones contain legitimate promoters, we used RT-PCR to confirm the in vitro and in vivo expressions of three antisense RNAs predicted by the antisense RIVET clones (Fig. 3). These data serve as the first demonstration of antisense transcripts generated from the E. faecalis chromosome during growth in a mammalian host. A recent study described the presence of several noncoding and antisense RNA species in E. faecalis (25). Those authors detected transcripts predicted by two of our RIVET antisense clones (RIVET antisense clones EF0867 and EF3260), providing further confirmation of the RIVET screen's role in predicting antisense RNAs in E. faecalis. Our data suggest that genome-wide antisense RNA expression occurs in E. faecalis during in vivo growth. In addition, this finding suggests that RIVET may be a useful method for the identification and characterization of the expression of noncoding RNAs.

When we tested whether the genes proB and ebrA (Table 2) were important for either biofilm formation or endocarditis, we found that OG1RF strains lacking either gene did not show any biofilm formation defects (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and that the ΔproB strain, but not the ΔebrA strain, was slightly attenuated in endocarditis (Fig. 4). These data emphasize that in vitro biofilm formation and endocarditis development are not necessarily correlated. The work presented here is the first report of a role for proB, encoding glutamate 5-kinase, in E. faecalis in vivo growth. Our finding differs from those reported previously for Listeria monocytogenes, where a proBA mutant was shown to be as virulent as the wild-type strain in mouse intraperitoneal and peroral infections (57). Previously reported work showed that ebrA is upregulated in biofilm cells and that lower numbers of cells of a strain lacking ebrA were recovered from biofilms grown on cellulose membranes than wild-type cells (4). A similar effect was not observed in the present study, in which biofilms were grown on coupons made of the fluoropolymer Aclar. This difference may be attributable to the chemical differences in the substrates on which the biofilms were grown.

We have shown here that the membrane protease Eep, which was transcriptionally activated early during the subdermal abscess infection (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), was required for effective E. faecalis virulence in an endocarditis model (Fig. 4) and that it affects cellular distribution during early biofilm formation in vitro (Fig. 5). Notably, the Δeep strain produces the greatest decrease in endocarditis virulence of any single-gene knockout that we have tested to date (approximately a dozen genes tested) (Fig. 4) (Frank and Dunny, unpublished). In E. faecalis, Eep is known to be involved in the proteolytic processing of several sex pheromone peptides that are located within the signal sequences of lipoproteins (1, 2, 13, 18); mature pheromones extracellularly induce conjugation in a class of large pheromone-responsive conjugative plasmids (e.g., pCF10 and pAD1) (17, 22). The sex pheromone-related function of Eep was characterized using cells grown in routine laboratory medium (2, 13), indicating that eep is expressed in vitro to some degree. Despite pregrowing the RIVET library inoculum to eliminate in vitro-expressed promoters, RIVET plasmids carrying the eep locus were isolated in vivo in this study and in biofilms (4). It is conceivable that a very low level of eep transcription, or transcription in a small subset of cells in a population, during growth in laboratory medium generates sufficient Eep enzymatic activity for the processing of the very low levels of pheromones that are secreted (9, 39). Such cells may not have been eliminated during the in vitro pregrowth because the selection agent, kanamycin, is not bactericidal against most enterococcal strains, even at the high levels used in this study. Since the biofilm and in vivo RIVET screens were carried out using a plasmid-free version of OG1RF, our data provide the first description of a function for Eep in E. faecalis that does not directly involve the processing of signaling molecules for pheromone-inducible conjugative plasmids. The observations that the level of eep locus transcription is increased during biofilm formation and under in vivo growth conditions and that the Δeep mutant has altered phenotypes in developing biofilms and causing endocarditis suggest that the protease has broader functions.

Eep belongs to the site 2 protease class of intramembrane proteases found in organisms ranging from bacteria to humans (62). Bacterial site 2 proteases have functions in both physiology and pathogenesis (35, 62); examples of these functions include sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (49), cell polarity in Caulobacter spp. (14), alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (47, 65), and toxin expression in Vibrio cholerae (36). A function for site 2 proteases in pathogenesis is consistent with our observation that an Eep-deficient strain was severely attenuated in forming vegetations on damaged heart valves. One hypothesis for the in vivo function of Eep is that it has a more general role in the processing of E. faecalis lipoproteins beyond the generation of mature conjugative pheromones (2, 13). A similar function has been attributed to an Eep homolog found in the bovine mastitis pathogen Streptococcus uberis (19). Alternatively, Eep may act as a structural component of the E. faecalis cell envelope or process other types of peptide signals that are important during biofilm growth and infection.

Finally, the fluorescent micrographs shown in Fig. 5 demonstrate that the loss of Eep leads to a visible phenotype in early in vitro biofilms. The lack of Eep shifts the cellular distribution from being generally uniform (Fig. 5A and C) to a discrete clustering phenotype (Fig. 5B and D). In addition, the diffuse extracellular labeling by the WGA lectin (used here primarily to visualize the cell envelope) also suggests that under these conditions, mutant biofilms may produce either more extracellular matrix or a matrix with higher levels of polysaccharides comprised of N-acetylglucosamine or sialic acid residues. Deciphering whether the biofilm cell distribution phenotype shown in Fig. 5 is specifically caused by the loss of Eep and addressing the relationship between these in vitro observations and the in vivo biofilm results are avenues of current investigation.

In conclusion, we have identified genes in the core genome of E. faecalis OG1RF that contribute to the ability of this important nosocomial pathogen to adapt to and survive in a mammalian host. These data revealed two significant and novel observations: (i) the membrane metalloprotease Eep is a major virulence determinant in E. faecalis, and (ii) multiple antisense RNA transcripts are expressed in E. faecalis during infection. This work also illustrates how RIVET screens provide useful information about the temporal activation of genes in a pathogen during infection. In addition, we have shown how the application of a single genetic technique under two different conditions led to the identification and confirmation of a new virulence determinant. The data presented here will provide a foundation for future studies that should begin to unravel the sensing and regulatory pathways that E. faecalis uses to adapt to and survive in its surroundings in a host.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Christopher Kristich and Katie Ballering for their advice on setting up and conducting the RIVET experiments and Petra Kohler, Olivia Chuang-Smith, Jillian Vocke, and Adam Spaulding for their instrumental roles in performing the endocarditis experiments.

This work was carried out in part using computing resources provided by the University of Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. Genome annotation was carried out with RAST, which is supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract number HHSN266200400042C. This research was supported by award number R01AI58134 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to G.M.D. A.M.T.B. received additional support from NIH medical scientist training grant number T32GM008244. K.L.F. was supported by award number F32AI082881 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, award number T32DE007288 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and award number 10POST3290026 from the American Heart Association.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institutes of Health, or the American Heart Association. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 December 2011

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. An FY, Clewell DB. 2002. Identification of the cAD1 sex pheromone precursor in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:1880–1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. An FY, Sulavik MC, Clewell DB. 1999. Identification and characterization of a determinant (eep) on the Enterococcus faecalis chromosome that is involved in production of the peptide sex pheromone cAD1. J. Bacteriol. 181:5915–5921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aziz RK, et al. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ballering KS, et al. 2009. Functional genomics of Enterococcus faecalis: multiple novel genetic determinants for biofilm formation in the core genome. J. Bacteriol. 191:2806–2814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayer AS, Coulter SN, Stover CK, Schwan WR. 1999. Impact of the high-affinity proline permease gene (putP) on the virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in experimental endocarditis. Infect. Immun. 67:740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beaman TC, et al. 1983. Specificity and control of uptake of purines and other compounds in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 156:1107–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bourgogne A, et al. 2008. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol. 9:R110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryan EM, Bae T, Kleerebezem M, Dunny GM. 2000. Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44:183–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buttaro BA, Antiporta MH, Dunny GM. 2000. Cell-associated pheromone peptide (cCF10) production and pheromone inhibition in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4926–4933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Camilli A, Beattie DT, Mekalanos JJ. 1994. Use of genetic recombination as a reporter of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:2634–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Camilli A, Mekalanos JJ. 1995. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 18:671–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castillo AR, Woodruff AJ, Connolly LE, Sause WE, Ottemann KM. 2008. Recombination-based in vivo expression technology identifies Helicobacter pylori genes important for host colonization. Infect. Immun. 76:5632–5644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2008. Characterization of the sequence specificity determinants required for processing and control of sex pheromone by the intramembrane protease Eep and the plasmid-encoded protein PrgY. J. Bacteriol. 190:1172–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen JC, Viollier PH, Shapiro L. 2005. A membrane metalloprotease participates in the sequential degradation of a Caulobacter polarity determinant. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1085–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiang SL, Mekalanos JJ, Holden DW. 1999. In vivo genetic analysis of bacterial virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:129–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chuang ON, et al. 2009. Multiple functional domains of Enterococcus faecalis aggregation substance Asc10 contribute to endocarditis virulence. Infect. Immun. 77:539–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clewell DB. 2007. Properties of Enterococcus faecalis plasmid pAD1, a member of a widely disseminated family of pheromone-responding, conjugative, virulence elements encoding cytolysin. Plasmid 58:205–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clewell DB, An FY, Flannagan SE, Antiporta M, Dunny GM. 2000. Enterococcal sex pheromone precursors are part of signal sequences for surface lipoproteins. Mol. Microbiol. 35:246–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denham EL, Ward PN, Leigh JA. 2008. Lipoprotein signal peptides are processed by Lsp and Eep of Streptococcus uberis. J. Bacteriol. 190:4641–4647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dornenburg JE, DeVita AM, Palumbo MJ, Wade JT. 2010. Widespread antisense transcription in Escherichia coli. mBio 1:e00024-10 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00024-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dunny GM, Brown BL, Clewell DB. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:3479–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunny GM, Johnson CM. 2011. Regulatory circuits controlling enterococcal conjugation: lessons for functional genomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14:174–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Facklam RR, Carvalho M, Teixeira LM. 2002. History, taxonomy, biochemical characteristics, and antibiotic susceptibility testing of enterococci, p 1–54 In Gilmore MS, et al. (ed), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fisher K, Phillips C. 2009. The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus. Microbiology 155:1749–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fouquier d'Herouel A, et al. 2011. A simple and efficient method to search for selected primary transcripts: non-coding and antisense RNAs in the human pathogen Enterococcus faecalis. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graham MR, et al. 2006. Analysis of the transcriptome of group A Streptococcus in mouse soft tissue infection. Am. J. Pathol. 169:927–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanin A, et al. 2010. Screening of in vivo activated genes in Enterococcus faecalis during insect and mouse infections and growth in urine. PLoS One 5:e11879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heydorn A, et al. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146(Pt 10):2395–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2007. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 57:131–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kristich CJ, Li YH, Cvitkovitch DG, Dunny GM. 2004. Esp-independent biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 186:154–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kristich CJ, et al. 2008. Development and use of an efficient system for random mariner transposon mutagenesis to identify novel genetic determinants of biofilm formation in the core Enterococcus faecalis genome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3377–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liang FT, Nelson FK, Fikrig E. 2002. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J. Exp. Med. 196:275–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lowe AM, Beattie DT, Deresiewicz RL. 1998. Identification of novel staphylococcal virulence genes by in vivo expression technology. Mol. Microbiol. 27:967–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maadani A, Fox KA, Mylonakis E, Garsin DA. 2007. Enterococcus faecalis mutations affecting virulence in the Caenorhabditis elegans model host. Infect. Immun. 75:2634–2637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makinoshima H, Glickman MS. 2006. Site-2 proteases in prokaryotes: regulated intramembrane proteolysis expands to microbial pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 8:1882–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matson JS, DiRita VJ. 2005. Degradation of the membrane-localized virulence activator TcpP by the YaeL protease in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16403–16408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mohamed JA, Huang DB. 2007. Biofilm formation by enterococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1581–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mutnick AH, Biedenbach DJ, Jones RN. 2003. Geographic variations and trends in antimicrobial resistance among Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997-2000). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakayama J, Ruhfel RE, Dunny GM, Isogai A, Suzuki A. 1994. The prgQ gene of the Enterococcus faecalis tetracycline resistance plasmid pCF10 encodes a peptide inhibitor, iCF10. J. Bacteriol. 176:7405–7408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neuhard J. 1983. Utilization of preformed pyrimidine bases and nucleosides, p 95–148 In Munch-Petersen A. (ed), Metabolism of nucleotides, nucleosides, and nucleobases in microorganisms. Academic Press, Inc, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 41. Orihuela CJ, et al. 2004. Microarray analysis of pneumococcal gene expression during invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 72:5582–5596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Osorio CG, Camilli A. 2003. Hidden dimensions of Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. ASM News 69:396–401 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Osorio CG, et al. 2005. Second-generation recombination-based in vivo expression technology for large-scale screening for Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection of the mouse small intestine. Infect. Immun. 73:972–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paulsen IT, et al. 2003. Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Science 299:2071–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pfaller MA, et al. 1999. Survey of blood stream infections attributable to Gram-positive cocci: frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates collected in 1997 in the United States, Canada, and Latin America from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. SENTRY Participants Group. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33:283–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Qiu D, Eisinger VM, Rowen DW, Yu HD. 2007. Regulated proteolysis controls mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:8107–8112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roggiani M, Schlievert PM. 2000. Purification of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A, p 59–66 In Evans TJ. (ed), Septic shock methods and protocols, vol 36 Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rudner DZ, Fawcett P, Losick R. 1999. A family of membrane-embedded metalloproteases involved in regulated proteolysis of membrane-associated transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:14765–14770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schlievert PM. 2007. Chitosan malate inhibits growth and exotoxin production of toxic shock syndrome-inducing Staphylococcus aureus strains and group A streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3056–3062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schwan WR, et al. 1998. Identification and characterization of the PutP proline permease that contributes to in vivo survival of Staphylococcus aureus in animal models. Infect. Immun. 66:567–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Scott DF, Kling JM, Kirkland JJ, Best GK. 1983. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with toxic shock syndrome, using polyethylene infection chambers in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 39:383–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. 2002. Differential expression of virulence-related genes in Enterococcus faecalis in response to biological cues in serum and urine. Infect. Immun. 70:4344–4352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Silby MW, Levy SB. 2008. Overlapping protein-encoding genes in Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Silby MW, Levy SB. 2004. Use of in vivo expression technology to identify genes important in growth and survival of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 in soil: discovery of expressed sequences with novel genetic organization. J. Bacteriol. 186:7411–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Slauch JM, Camilli A. 2000. IVET and RIVET: use of gene fusions to identify bacterial virulence factors specifically induced in host tissues. Methods Enzymol. 326:73–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sleator RD, Gahan CG, Hill C. 2001. Identification and disruption of the proBA locus in Listeria monocytogenes: role of proline biosynthesis in salt tolerance and murine infection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2571–2577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Talaat AM, Lyons R, Howard ST, Johnston SA. 2004. The temporal expression profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4602–4607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomason MK, Storz G. 2010. Bacterial antisense RNAs: how many are there, and what are they doing? Annu. Rev. Genet. 44:167–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tight RR, Prior RB, Perkins RL, Rotilie CA. 1975. Fluid and penicillin G dynamics in polyethylene chambers implanted subcutaneously in rabbits. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 8:495–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Toledo-Arana A, et al. 2009. The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 459:950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Urban S. 2009. Making the cut: central roles of intramembrane proteolysis in pathogenic microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:411–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vadyvaloo V, Jarrett C, Sturdevant DE, Sebbane F, Hinnebusch BJ. 2010. Transit through the flea vector induces a pretransmission innate immunity resistance phenotype in Yersinia pestis. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vebø HC, Snipen L, Nes IF, Brede DA. 2009. The transcriptome of the nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecalis V583 reveals adaptive responses to growth in blood. PLoS One 4:e7660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wood LF, Ohman DE. 2009. Use of cell wall stress to characterize sigma 22 (AlgT/U) activation by regulated proteolysis and its regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 72:183–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Xu Q, Dziejman M, Mekalanos JJ. 2003. Determination of the transcriptome of Vibrio cholerae during intraintestinal growth and midexponential phase in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1286–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yarwood JM, McCormick JK, Paustian ML, Kapur V, Schlievert PM. 2002. Repression of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator in serum and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184:1095–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.