Abstract

The adaptation of viruses to new hosts is a poorly understood process likely involving a variety of viral structures and functions that allow efficient replication and spread. Canine parvovirus (CPV) emerged in the late 1970s as a host-range variant of a virus related to feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Within a few years of its emergence in dogs, there was a worldwide replacement of the initial virus strain (CPV type 2) by a variant (CPV type 2a) characterized by four amino acid differences in the capsid protein. However, the evolutionary processes that underlie the acquisition of these four mutations, as well as their effects on viral fitness, both singly and in combination, are still uncertain. Using a comprehensive experimental analysis of multiple intermediate mutational combinations, we show that these four capsid mutations act in concert to alter antigenicity, cell receptor binding, and relative in vitro growth in feline cells. Hence, host adaptation involved complex interactions among both surface-exposed and buried capsid mutations that together altered cell infection and immune escape properties of the viruses. Notably, most intermediate viral genotypes containing different combinations of the four key amino acids possessed markedly lower fitness than the wild-type viruses.

INTRODUCTION

Ongoing viral evolution may generate important phenotypic variants, including strains that differ in host range, transmission mechanisms and efficiency, tissue tropism, antigenicity, and/or virulence. Although these novel biological functions often require multiple and concerted genomic changes, how such combinations of mutations can arise and be favored by natural selection is unclear. The complexity of the evolutionary pathways leading to the appearance of phenotypic variants is compounded when they alter the host range of viruses, as mutations may have different fitness consequences in different host species (24, 27, 32). Mutations may also be subject to complex selection pressures in the same host when, for example, receptor binding and antibody recognition sites overlap on the viral capsid, so that selection pressures differ between immunologically naïve and immune individuals (31). Understanding the processes by which viruses acquire new phenotypes in the face of such complex selective environments is critical for improving the prediction, prevention, and control strategies for emerging viral diseases.

Feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) and closely related viruses that infect many hosts within the order Carnivora have undergone processes of cross-species transmission and adaptation during the last 3 decades, providing a powerful opportunity to examine the evolution and adaptation of a novel pandemic virus in the context of new host environments. Canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2) is a host-range variant of a virus closely related to FPV that gained the ability to infect dogs through the acquisition of capsid mutations that altered the interaction of virus capsids with the transferrin receptor type 1 (TfR) on the surface of canine cells (14, 29). CPV-2 was the original virus strain in dogs that spread worldwide during 1978 and that was completely replaced during 1979 and 1980 by a new variant (CPV-2a). The CPV-2a strain is genetically and antigenically distinct from CPV-2 (17, 22) and is presumably better adapted to its canine host since it replaced CPV-2 in nature. It is now clear that the emergence of CPV involved a number of host-switching events between cats, dogs, raccoons, and possibly other carnivores, with multiple transfers occurring among the different hosts (2). While the emergence of CPV-2a was previously attributed to host adaptation in dogs, recent studies have shown that this adaptive process likely involved transfer of CPV-2a to and from raccoons (2). Raccoon infection also involved a host-range change in the virus, as the raccoon viruses lost the canine host range and appeared to carry host-specific mutations that were likely adaptive for raccoons (2). The emergence of CPV-2a also involved a host-range expansion, as the original CPV-2 did not replicate in cats, while CPV-2a isolates replicated efficiently and caused disease in cats (28). This represented a novel host-adaptation event, as CPV-2a did not show significant reversion back to the original FPV sequences (28). CPV-2a isolates also showed altered binding to the feline TfR compared with either FPV or CPV-2 (9) and were antigenically variant at a major antigenic epitope on the capsid (22).

All CPV-2a-derived viruses isolated from dogs share four unique amino acid replacements compared with CPV-2, at residues 87, 101, 300, and 305 in the major capsid protein VP2 (Table 1; Fig. 1). The CPV-2a-specific residues at 87 (Leu) and 101 (Thr) were likely acquired during evolution of the virus in raccoons, while the changes at 300 (Gly) and 305 (Tyr) were acquired when the virus transferred back to the canine host (2). Importantly, residues 87, 300, and 305 all lie within the proposed binding footprint of the TfR, while residue 101 lies close to residue 87, just below the capsid surface (see Fig. 3) (7). In the 3 decades since its emergence, the CPV-2a-derived variants have acquired many additional point mutations, and some codons have changed multiple times. For example, VP2 residue 426 is Asn in CPV-2a but Asp in CPV-2b-designated variants (16) and Glu in CPV-2c-designated variants (4), while VP2 residue 300 has been found to be Ala, Gly, Val, Asp, and Pro in different viruses, and some of those variant residues alter the host range and antigenicity of the viruses (2, 11, 19).

Table 1.

Mutational differences between CPV-2 and CPV-2ba

| Genomic nucleotide no. | Genomic region | Sequence |

Residue |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPV-2 | CPV-2b | CPV-2 | CPV-2b | ||

| 59 | 5′ noncoding | G | A | ||

| 97 | 5′ noncoding | C | T | ||

| 1649 | NS1 residue 459 | ATT | ATC | Synonymous | Synonymous |

| 1903 | NS1 residue 544 | TAT | TTT | Tyr | Phe |

| 2198 | NS1 residue 642 | ACA | ACG | Synonymous | Synonymous |

| 2198 | NS2 residue 152 | ATG | GTG | Met | Val |

| 3045 | VP2 residue 87 | ATG | TTG | Met | Leu |

| 3088 | VP2 residue 101 | ATT | ACT | Ile | Thr |

| 3685 | VP2 residue 300 | GCT | GGT | Ala | Gly |

| 3699 | VP2 residue 305 | GAT | TAT | Asp | Tyr |

| 3909 | VP2 residue 375 | AAT | GAT | Asn | Asp |

| 4062 | VP2 residue 426 | AAT | GAT | Asn | Asp |

| 4745 | 3′ noncoding | T | C | ||

| 4789 | 3′ noncoding | T | C | ||

| 4881 | 3′ noncoding | C | T | ||

| 5026 | 3′ noncoding | Deletion | G | ||

| 5029 | 3′ noncoding | T | Deletion | ||

Gray shading indicates the residues examined in detail in this study. Bold indicates a nucleotide difference.

Fig 1.

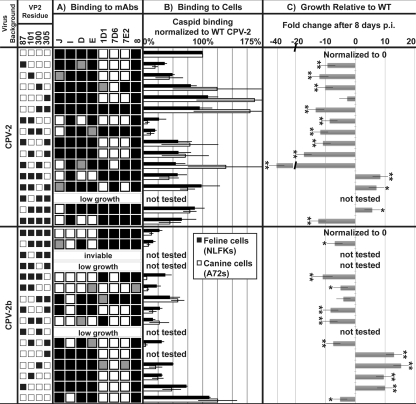

Ligand-binding properties and relative fitness of wild-type (WT) and intermediate viruses. The left-most columns indicate the virus background and combination of four VP2 residue changes used for each intermediate virus, with white squares indicating CPV-2 residues (87Met, 101Ile, 300Ala, 305Asp) and black squares indicating CPV-2b residues (87Leu, 101Thr, 300Gly, 305Tyr). (A) Virus binding profiles for 8 MAbs as determined by HI assay. Strong (black), intermediate (gray), and weak (white) binding for each MAb was defined by its wild-type CPV-2 and CPV-2b binding titers, as wild-type virus specificity for these MAbs is well characterized (22). (B) Virus binding and uptake in feline and canine cells measured by flow cytometry. The median fluorescent intensity (MFI) relative to CPV-2 binding from three independent experiments was averaged, and the standard error of the mean is shown. (C) Relative fitness of intermediate viruses relative to wild-type CPV-2 (top half) or CPV-2b (bottom half) following 7.5 days of replication in feline cells. Average fold changes in intermediate relative to wild-type PHRs from three or more competition assays are shown. Asterisks indicate that the change in PHR is significantly different from zero or that there is no change over time, with P being <0.05 (*) or <0.005 (**).

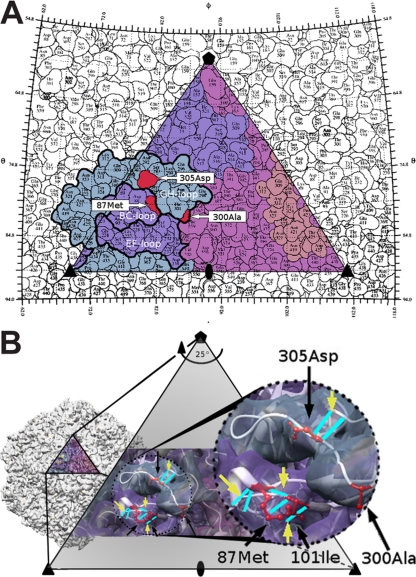

Fig 3.

(A) Asymmetric unit of the CPV-2 capsid structure, showing the spatial relationships among the surface-exposed residues 87, 300, and 305 in red. Each VP2 peptide has a different color, and three key surface loops are outlined in black. (B) A closer, three-dimensional representation of the CPV-2 structure, showing the four residues of interest in red and indicating with yellow arrows all potential hydrogen bonds that may be altered when these residues are changed to the CPV-2b sequence.

The structures of CPV and FPV capsids have been determined by X-ray crystallography, revealing that the capsid is an icosahedron with T equal to 1, assembled from 60 subunits of a combination of VP1 (about 5 to 7 copies) and VP2 (53 to 55 copies) (1, 30, 35). VP1 and VP2 share most of their sequences, as VP2 is completely contained within the sequence of VP1. The common VP structure includes a central core that is made up of an eight-stranded β barrel, where loops between the β strands interact to assemble the capsid and also form most of the capsid surface (30, 35). The TfR binding site on the capsid is on a raised region of the structure (the 3-fold spike) and overlaps extensively with one of the two antigenic sites on the capsid surface, termed sites A and B (6, 26). Both antibody-selected and host-range-controlling sites on the capsid fall within the antigenic sites, with VP2 residue 300 being in the middle of site B, residue 426 being within site A, and residues 87 and 305 being within an overlapping region of the antibody binding footprints for sites A and B (6).

To study the impact of the four mutations at VP2 residues 87, 101, 300, and 305 on CPV binding and infection properties, the order and/or combinations in which these mutations may have evolved, and the nature of the fitness pathways followed during the process of viral adaptation, we examined several biological properties of viruses that represent all intermediate combinations of the four CPV-2a-clade-defining VP2 residues in the backgrounds of viral genomes from the CPV-2 and CPV-2a clades. Importantly, none of these potential intermediate viruses have ever been isolated from clinical canine cases, although some of the mutational combinations are present in viruses from raccoons, albeit in different, host-specific genetic backgrounds (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Norden Laboratory feline kidney (NLFK) cells and A72 canine fibroblasts were grown in a 1:1 mixture of McCoy's 5A and Liebovitz L15 media with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) (growth medium). Parvoviruses were derived from infectious plasmid clones of CPV-2 (CPV-d) and CPV-2b (CPV-39) strains, as previously described (16). Intermediate viruses were created from the same infectious plasmid clones using either the GeneEditor in vitro site-directed mutagenesis system (Promega, Madison, WI) or the Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit (Finnzymes, Woburn, MA). In all cases, the mutated region of the VP2 gene was sequenced to confirm that only the desired mutations were present, and in some cases, the mutated region was recloned into the appropriate infectious plasmid background to ensure that no additional mutations were present in the genome. Capsids were purified from infected cells by concentration with polyethylene glycol, followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation and dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (1, 12).

Virus infectivity assays.

For viability and infection assays, NLFK cells seeded at 2 × 104 cells/cm2 in 25- or 75-cm2 dishes were incubated overnight at 37°C. To prepare infectious virus, cells were incubated with 5 μg plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 4 h. Transfected cell cultures were grown for 7 days with one passage. To assess virus infectivity, cells were inoculated with first-passage-virus supernatant and then incubated for 7 days. Viral infection was assessed by examining cells for viral proteins, where coverslips were fixed at 2 days posttransfection or postinfection and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (immunofluorescence assay). Transfected or infected cultures were frozen, thawed, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Virus titers were tested in hemagglutination (HA) assays using feline erythrocytes in bis-Tris-buffered saline (pH 6.2 at 4°C) (20, 25).

Virus detection by fluorescent-antibody staining.

Fixed cells were stained for virus with Alexa 488-labeled anti-nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) monoclonal antibody (MAb) (MAb CE10) (37) and/or Alexa 594-labeled anticapsid MAb (MAb 8) (20). Antiviral antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.05% sodium azide (permeabilization solution) and incubated with cells for 1 h at room temperature. Stained coverslips were analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse TE300 epifluorescent microscope.

Antigenic analysis of viruses.

Antigenic testing of viruses was performed using a hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay with a panel of mouse and rat MAbs prepared against FPV, CPV-2, or CPV-2b capsids (18, 20, 22) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Wild-type virus specificity of monoclonal antibodies used to test intermediate virus antigenicity in the hemagglutination inhibition assaya

| MAb | Species | Immunizing antigen (type) | Binding site on capsid | CPV type specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | Rat | FPV-c | B | 2 |

| I | Rat | FPV-c | A | 2 |

| D | Rat | FPV-c | B | 2 |

| E | Rat | FPV-c | B | 2 |

| 1D1 | Mouse | CPV-39 (2b) | ND | 2b |

| 7D6 | Mouse | CPV-39 (2b) | ND | 2b |

| 7E2 | Mouse | CPV-39 (2b) | ND | 2b |

| 8 | Mouse | CPV-a (2) | B | All |

Virus binding and uptake by feline and canine cells.

Feline or canine cells were seeded at 2 × 104 cells/cm2 in 12-well tissue culture plates. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, cells were washed twice with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (binding medium) at 37°C. Wild-type and intermediate virus binding and uptake were examined by incubating cells with 15 μg/ml of purified virus for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with binding medium, dissociated with a brief exposure to trypsin, transferred to a 96-well, V-bottom plate, and then washed once with PBS containing 1% ovalbumin, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.01% NaN3 (wash solution), before being fixed for 20 min in intracellular (IC) fixation buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Cells washed three times with permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) were stained with Alexa 488-labeled anticapsid MAb 8 (20) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were resuspended in wash solution and analyzed using a GuavaCyte flow cytometer (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo (version 9) software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Competition assays to assess relative viral fitness in cell culture.

Virus mixtures were prepared for each intermediate virus and its respective wild-type virus at 10:1, 1:1, and 1:10 volume-to-volume ratios. NLFK cells seeded at 2 × 104 cells/cm2 in 96-well tissue culture plates were washed after 24 h with DMEM with 0.1% BSA (infection medium) at 37°C. Each virus mixture was incubated in a plate with cells for 1 h at 37°C, and then the cells were washed twice with infection medium and maintained at 37°C for 2 or 7.5 days in growth medium. Cultures were frozen at −80°C, thawed rapidly at 37°C, transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate, and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min to pellet cellular debris. The supernatants were used for PCR and sequencing of the viral DNA. Two types of replicate competition assays were performed using either the same input stock viruses (competition replicates) or different input stock mixtures (input replicates).

PCR, sequencing, and analysis.

Phusion hot-start DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), CPV primers (forward, 5′-GAAAACGGATGGGTGGAAATCACAGC-3′; reverse, 5′-TATTTTGAATCCAATCTCCTTCTGG-3′), and 30 cycles of 0:10 min at 98°C, 0:30 min at 54°C, and 2:15 min at 72°C amplified the midportion of the VP2 gene covering codons 87, 101, 300, and 305. DNA products were purified using QIAquick 96 PCR purification kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and sequenced by Cornell University's Core Laboratories Center using the same primers. Peak heights were measured from sequence traces using 4Peaks software (Mekentosj, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and peak height ratios (PHRs) were calculated for nucleotides that differed in sequence between each pair of input viruses. PHRs were defined as intermediate virus relative to wild-type virus or, in the case of the wild-type competition, as CPV-2b relative to CPV-2. Changes in PHRs over time were calculated, and fold increases or decreases after 2 or 7.5 days of cell culture incubation were determined. We defined an increase in PHR over time as indicating that the intermediate virus grew better than wild type, whereas a decrease in PHR indicated that the wild-type virus grew better. Where more than one nucleotide varied between the two input viruses, the fold changes in PHRs were calculated for each site independently and also averaged for all variant sites.

Statistical analysis for competition assays.

To test for a statistically significant change in PHRs over time, mixed models were fitted to the data using the Proc Mixed program in the SAS package (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for each pairwise competition at both 2 days (data not shown) and 7.5 days postinfection. The predictors used in the mixed models were virus pair, competition replicate, input replicate, and ratio (when all three ratios were analyzed together). Each competition replicate was modeled by its corresponding input replicate, and each ratio was modeled by virus pair. Least-squares means were compared, adjusting for multiplicity, using the Tukey-Kramer method. Data were analyzed for each residue and input ratio independently (data not shown), as well as for all residues and input ratios together.

RESULTS

We prepared 30 viruses with all single, double, triple, and quadruple VP2 mutations from each wild-type virus background and tested these along with the 2 wild-type viruses. The available wild-type infectious clone used to represent the newer CPV-2a-like clade of viruses had an Asp at VP2 residue 426, making it the CPV-2b antigenic type. After the transfection of NLFK cells, 26 of the 30 intermediate viruses replicated well enough for further testing (Fig 1). Four viruses replicated poorly in NLFK cells, and three of these were in the CPV-2b background and involved changes at residue 101 or 300 or the combined change of residues 101 and 305 (Fig. 1). A fourth virus that replicated to very low levels was the triple intermediate in the CPV-2 background that gave the same combination of residues (87Leu, 101Ile, 300Gly, and 305Tyr) as one of the CPV-2b mutants that grew poorly.

Antigenic variation.

The antigenic structure of the capsid changed significantly between CPV-2 and CPV-2a/b, with both the loss and gain of epitopes recognized by groups of mouse and rat MAbs (18, 20, 22). Multiple residues were involved in altering each antigenic site: the binding of the CPV-2-specific antibodies (MAbs D and J) was largely controlled by residues 87Met and 101Ile, while binding of CPV-2b-specific antibodies (MAbs 1D1, 7D6, and 7E2) was largely due to the change of residue 300 from Ala to Gly (Fig. 1A). MAbs E and I gave unique binding patterns, and the results were not directly reciprocal between intermediate viruses where the same residues were changed in the two virus backgrounds. MAb E showed reduced binding to intermediate CPV-2 when residues 101 and 300 were changed together in the different double, triple, and quadruple mutants. However, in the CPV-2b background, more than one combination of changes resulted in a recovery of MAb E binding. The binding of MAb I to CPV-2 was never lost, whereas all triple mutants of CPV-2b gained MAb I binding. These results indicate that the additional differences between the CPV-2 and CPV-2b capsids (Table 1) influence antibody binding by MAbs E and I.

Receptor binding.

The binding and uptake of viruses in feline NLFK and canine A72 cells were assessed using flow cytometry (Fig. 1B). Comparing the wild-type viruses showed that CPV-2 capsids bound to feline and canine cells at 5- to 20-fold higher levels than did CPV-2b, as previously reported (9). Residues 87Met and 101Ile together were responsible for much of the higher binding seen in CPV-2, and changing these sites in CPV-2 to the CPV-2b residues, alone and in concert, resulted in up to a 4-fold reduction in feline cell binding and up to a 15-fold reduction in canine cell binding. However, changing these two residues in CPV-2b to the CPV-2 sequence resulted in only a modest 1.5- to 4-fold increase in cell binding, and CPV-2b cell binding reached CPV-2 levels only when all four VP2 residues were changed simultaneously (Fig. 1B).

Relative fitness in cultured feline cells.

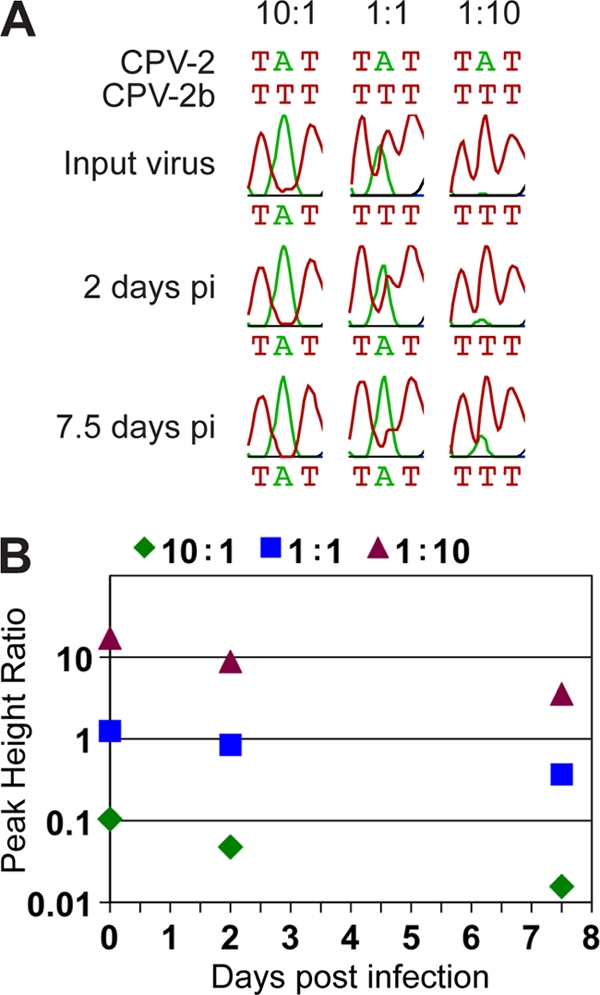

The effects of the different mutations on the relative fitness of each of the intermediate viruses were determined by growing each virus in coculture with its own wild-type virus in highly permissive feline NLFK cells. We determined the proportion of each of the viruses in the input mixture and at days 2 and 7.5 postinfection from the relative peak heights at each different position in the sequence trace (Fig. 2). Analyzing sequence data in this manner has successfully been used to identify heterozygotes (10), to detect single nucleotide polymorphisms in pooled samples of DNA (3, 34, 36), and to distinguish viral variants (8). Figure 1C shows the change in proportion of each mutant virus compared with its own wild type after 7.5 days of incubation. This shows that most single and double mutants were outcompeted by their respective wild types, while, surprisingly, the triple mutants infected or replicated more efficiently (P < 0.005 in most cases). This suggests that there are complex trade-offs in the effects of capsid mutations on viral functions, as revealed by this simple tissue culture assay.

Fig 2.

(A) Sequence trace data for the variable nucleotide in the VP2 codon 87 showing an increase in CPV-2 (green peak for adenine) and a decrease in CPV-2b (red peak for thymine) over time at each of the three input ratios of virus (10:1, 1:1, and 1:10). Traces are displayed using Geneious software (5). (B) Graphical representation of the change in PHR of CPV-2b relative to CPV-2 over time at each of the input ratios shown in panel A. The decrease in PHR over time shows that the second virus (CPV-2) replicates to higher levels than the first (CPV-2b). pi, postinfection.

In general, most CPV-2-derived intermediate viruses had lower replication fitness than wild-type CPV-2 in these feline cells (Fig. 1C). Changing VP2 residues 87 and 300 together in CPV-2 had the greatest effect and resulted in a 40-fold decrease in the intermediate genome compared to the wild-type CPV-2 genome after 7.5 days incubation (P < 0.0001). Changing residue 305 alone resulted in a virus that replicated to similar levels as wild-type CPV-2. Interestingly, the three triple mutants tested in the CPV-2 background replicated significantly better than wild-type CPV-2, as evidenced by a 5-fold or greater increase after 7.5 days (P ≤ 0.0298). However, changing all four residues in the CPV-2 background resulted in a virus less fit than wild-type CPV-2, matching similar results for the wild-type CPV-2b, which grew to lower levels in cultured feline cells than did CPV-2 (Fig. 2 and data not shown).

The CPV-2b-derived intermediates showed a similar fitness pattern, with single and double mutants being of similar or lesser fitness than wild-type CPV-2b and triple mutants having greater fitness by up to 15-fold at 7.5 days postinfection (P < 0.0001). Some of the CPV-2b-derived mutants with changes of residue 87 or 101 did not produce viable infectious viruses, and we confirmed that this was due to the specific mutations and not to problems with the genomic or plasmid background by recloning the segments containing the changes into fresh infectious plasmid clone backgrounds.

Modeling CPV-2b structural changes.

Examining the structure of the capsid shows that all four residues reside on the shoulder of the 3-fold spike, with residues 87 and 101 falling within the BC loop of one VP2 molecule, which interacts closely with the GH loop of a second VP2 that contains residues 300 and 305 (Fig. 3A) (35). Introducing the CPV-2b residues at positions 87, 101, 300, and 305 would be predicted to alter the flexibility of these surface loops and changes the hydrogen-bond interactions, as shown in Fig. 3B.

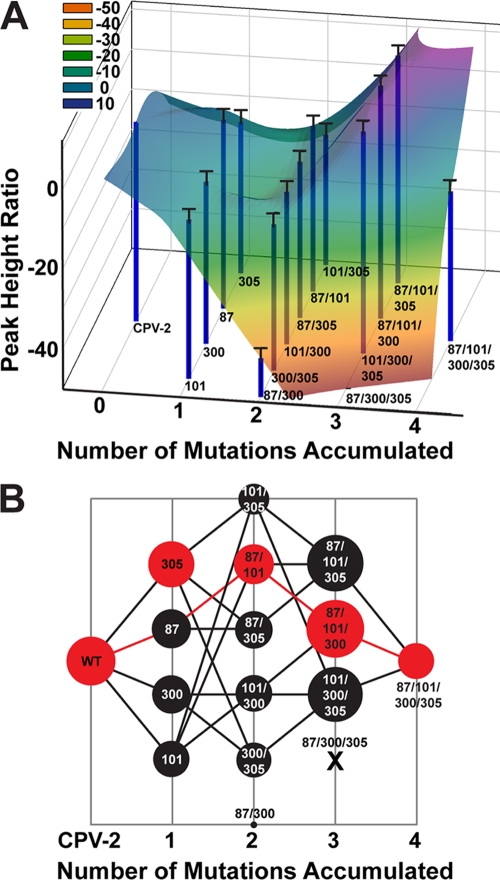

Fitness landscape of intermediate viruses.

The data generated here can be used to infer a fitness landscape for CPV in the context of the in vitro test system used, with the example shown here (Fig. 4A) representing the relative fitness of each CPV-2-derived virus in sequence space for this test environment. Importantly, this in vitro test system allows us to collect experimental fitness data that provide an initial understanding of the evolutionary pathways followed by CPV during the process of host adaptation. In the style of Weinreich et al. (33), Fig. 4B shows potential evolutionary trajectories, with pathways between the largest circles being the most parsimonious because they allow passage through the shallowest fitness troughs. Even in this simple in vitro model utilizing a single cell type, it is clear that the virus had to traverse a complex fitness landscape, with significant fitness valleys that would have clearly limited the number of viable evolutionary pathways that could have been followed encountered during the evolution of CPV-2 to CPV-2a. In addition, the fitness landscape suggests that certain orders of mutational acquisition were more likely than others, with changes at residues 87 and 101 being favored before changes at residue 300 (Fig. 4B). Importantly, this pattern matches results from a phylogenetic analysis of canine and raccoon CPV isolates, in which the mutations at residues 87 and 101 preceded those at residues 300 and 305 (2).

Fig 4.

Graphical representations of the relative fitness of CPV-2 intermediate viruses. (A) Adaptive landscape of the CPV-2 mutational intermediates tested here, showing the fitness effects of the four key VP2 residues that define the difference between the newer CPV-2a clade and the older CPV-2 clade. Each individual blue bar and corresponding black error bar represent PHR values following 7.5 days of infection in cultured feline cells (top half of Fig. 1C). Wild-type CPV-2 (left) is assigned a PHR value of zero; other PHRs are normalized to this value. On the right is the quadruple mutant in the CPV-2 background, representing a potential ancestral state of the CPV-2a clade. The x axis represents the number of mutations from wild-type CPV-2, and the various combinations of single, double, and triple mutations are distributed along the y axis in an arbitrary fashion. The numbers below each bar indicate which residues are changed from the CPV-2 sequence. An overlay colored to match PHRs provides a graphical representation of the landscape, showing fitness valleys and peaks. (B) Bubble plot showing the evolutionary pathways available to CPV-2 during its adaptation to dogs. The x and y axes are as described above. Peak height ratios were shifted onto a positive scale and multiplied by the same arbitrary scaling factor to allow the smallest and largest values to be visualized on the same plot as circles of various diameters. The largest circle for each number of mutations is shown in red. Two intermediate viruses in the CPV-2 background had either significantly reduced fitness (changes at VP2 87/300) or were nonviable (changes at VP2 87/300/305, marked by an X), effectively eliminating evolutionary pathways that use these combinations from plausible mutational trajectories. Lines indicate the remaining potential pathways, with the most parsimonious (i.e., shallowest) evolutionary pathway highlighted in red.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of the CPV strains currently circulating in dogs involved two steps that each required the acquisition of multiple capsid mutations: the change from an FPV-like virus to CPV-2 and the change from CPV-2 to CPV-2a. Here, we examined the structural and functional relationships of the four conserved capsid mutations that distinguish the original and newer CPV strains by preparing all of the putative evolutionary intermediates between those viruses. The data obtained clearly show that these changes worked in concert to determine different aspects of viral phenotype. While intermediates between these two virus clades have not been isolated from dogs, some intermediate mutations have been identified in raccoons (2), albeit in unique, host-specific genetic backgrounds, suggesting that the evolutionary trajectory of these viruses was facilitated by passage through an alternative host.

While most of the intermediates showed reduced fitness in culture compared to the wild-type viruses, 3 of the 15 CPV-2b-derived intermediate viruses and 1 CPV-2-derived virus grew very poorly and could not be recovered in an infectious form for analysis. Viruses bearing 87Leu, 101Ile, 300Gly, and 305Tyr failed to grow in either the CPV-2 background (a triple mutant with mutations at residues 87, 300, and 305) or the CPV-2b background (virus with a single reversion at site 101), which indicates that this constellation of residues is not well tolerated and less likely to be a true intermediate combination occurring during the early evolution of CPV.

Residue 300 and the adjacent residue 299 in VP2 have previously been shown to influence TfR and antibody binding (11, 15, 19, 26), and we now show that surface-exposed residues 87 and 305, as well as the closely positioned and buried residue 101, also play important roles in defining both of those binding activities. We do not yet have structures for the CPV-2a or CPV-2b capsids, but modeling the changes in the known CPV-2 or FPV capsid structures provides some predictions about the likely effects of changing different residues on the structure (Fig. 3B).

Mutations that change VP2 residues 87, 101, and 305 are all predicted to introduce changes in the geometry of the capsid structure due to both the substitutions of the amino acid side chains and the loss or gain of hydrogen bonds. Specifically, the change of residue 101 from Ile to Thr introduces a shorter side chain and a gain in polarity, so that the participation of 101Ile in a hydrogen bond with Met87 is likely lost (Fig. 3B). Two other hydrogen bonds arise from main chain interactions of the 101Ile, and introducing the shorter side chain may also cause a disruption of loop geometry that leads to loss of these main chain interactions. Similarly, the change of residue 87 from Met to Leu introduces a smaller side chain and causes the loss of the sulfur atom. The Met participates in two hydrogen bonds that would likely be disrupted, resulting in loop rearrangement. Finally, the Asp-to-Tyr change of residue 305 causes the loss of a negative charge and introduces a bulkier side chain. The Asp is involved in hydrogen bonding that stabilizes the GH loop, so that the Tyr substitution likely causes loss of these stabilizing bonds, making the loop more flexible.

Antigenic variation.

Each of the three surface-exposed residues influenced the antigenic structure of the viruses both alone and in concert with other changes, as expected, since the residues fall within antigenic sites A and B on the capsid. Interestingly, changing the buried residue 101 also altered the antigenic structure, indicating that modifications at this site alter the BC loop structure and change the capsid surface. Antigenic selection likely played a role in the replacement of CPV-2 by CPV-2a (21), as the global population of dogs developed significant levels of antibody against CPV-2 within 2 years that may have selected for the variant antigenic forms of the CPV-2a and later CPV-2b capsids (18, 20, 22).

Control of receptor binding.

CPV-2 binds feline and canine cells to a higher level than does CPV-2b (9), and here we show that both residue 87 and residue 101 influenced that binding, with only a minimal contribution from residue 305. In previous studies, changes of VP2 residues 299 and 300 to Glu and Asp, respectively, have proven to be particularly effective in altering the host range. The change of residue 300 from Ala to Asp has previously been selected by growth of CPV-2 in feline cells in culture, and that reduced infection for canine cells (11, 19), while natural raccoon isolates with 300Asp and other changes also lost the ability to infect canine cells (2). A CPV-2 mutant with only the VP2 residue 299 Gly-to-Glu substitution completely lost the ability to bind the canine TfR and infect canine cells (15, 26). It appears that these host-range changes are associated with changes in the surface structure and flexibility of capsid surface loops. Residue 300Asp forms a salt bridge with 81Arg in an adjacent VP2 subunit that would stabilize the structure (11), while the 300Gly in CPV-2a would introduce more flexibility into that surface loop. The latter change likely aids virus binding to the canine TfR, which has an additional glycosylation site in the virus-binding region compared with the feline TfR (13).

Relative fitness.

To examine the relative effects of the different combinations of mutations on virus infection and replication, we developed an assay for directly comparing cell infection and replication of each intermediate virus and its wild type in feline cell culture. Although this system clearly does not recapitulate the natural history that occurred during the selection of CPV-2a over CPV-2 in dogs around the world, it does allow us to examine one aspect of viral replication in a single cell type that wild-type carnivore parvoviruses can infect with similar efficiency. Notably, single and double mutations reduced the replication of the viruses, while virus with many triple combinations of mutations showed increased fitness over their respective wild-type genotypes. Although we do not yet have a clear explanation for this unusual effect, it does illustrate the complexity of the evolutionary pathways that would have been followed by the virus, particularly as the fitness landscape is characterized by major valleys that would have thwarted host adaptation (Fig. 4).

Similarly, although we have not found any of the CPV-2/CPV-2a intermediate mutational combinations in clinical isolates from dogs, viruses with various combinations of residues 87, 101, 300, and 305 are commonly found in raccoons (2). Phylogenetic analysis of these isolates showed that raccoon viruses that fall between the CPV-2 and CPV-2a clades have CPV-2a mutations at residues 87 (Leu) and 101 (Thr) but unique, host-specific changes at residue 300 (Asp) and, occasionally, residue 305 (His instead of the older CPV-2 Asp) (2). This suggests that the acquisition of at least some of these mutations may have arisen in viruses that were infecting raccoons, but the unique mutations at residues 300 and 305 indicate that raccoons provide a different selective environment than dogs.

Although the four residues tested represent key differences between the CPV-2 and CPV-2a clades, several other nucleotide differences in the genomes of the two tested wild-type clones (CPV-2 and CPV-2b) may be influencing both their phenotypes and fitnesses (Table 1). For example, the CPV-2b-derived intermediate virus with all four residues changed to CPV-2 sequences was still outcompeted by wild-type CPV-2b, indicating that the viral background possesses other mutations that affect growth in feline cell culture compared with wild-type CPV-2. It is unclear which of these other mutations might be playing a role and how they influence in vitro fitness. The wild-type CPV-2 and CPV-2b plasmid clones used in these studies were prepared from viruses that had been passed only a small number of times in cell culture (16). They differ at seven nucleotide positions in noncoding sequences, at three nucleotide positions in the nonstructural ORFs (including nonsynonymous changes at NS1 codon 544 and NS2 codon 152), and by two nonsynonymous changes of VP2 codons 375 and 426 (Table 1). While these changes do not define the differences between the CPV-2 and CPV-2a clades in dogs (2, 23), these single nucleotide polymorphisms may also be influencing the properties of the viruses, at least in cell culture.

Precisely documenting the adaptation of a virus to a new host is critical to understanding viral emergence. Our results indicate that while the key mutations required for host adaptation may arise freely, there are only a limited number of evolutionary pathways that the virus can follow and that lead to successful host adaptation, and this complexity will reduce the frequency of such host transfer events. In addition, it is clear not only that multiple mutations are required but also that many of these mutations act in concert and may need to be selected simultaneously to overcome host fitness barriers. Furthermore, as seen here with cellular receptors and antibodies, combinations of changes can affect multiple interactions with the host concurrently, resulting in complex selection pressures at these sites. In sum, this study provides a clearer picture of the complexities involved in an important adaptive event that involved multiple host transfers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shamil Sadigov from the Cornell Statistical Consulting Unit for his help with the statistical analysis of the competition data. We also thank Kai-Biu Shiu for his assistance with intermediate virus cloning and Virginia Scarpino and Wendy Weichert for their expert technical support.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants AI28385 and AI092571 to C.R.P. and GM080533 to E.C.H. K.M.S. was supported by NIH training grant RR007059 to Douglas D. McGregor, and I.P. was supported by Marie Curie Fellowship PIOF-GA-2009-236470.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Agbandje M, McKenna R, Rossmann MG, Strassheim ML, Parrish CR. 1993. Structure determination of feline panleukopenia virus empty particles. Proteins 16:155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison AB, et al. The role of multiple hosts in the cross-species transmission and emergence of a pandemic parvovirus. J. Virol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amos CI, Frazier ML, Wang W. 2000. DNA pooling in mutation detection with reference to sequence analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66:1689–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buonavoglia C, et al. 2001. Evidence for evolution of canine parvovirus type 2 in Italy. J. Gen. Virol. 82:3021–3025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drummond AJ, et al. 2010. Geneious v5.3. Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hafenstein S, et al. 2009. Structural comparison of different antibodies interacting with parvovirus capsids. J. Virol. 83:5556–5566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hafenstein S, et al. 2007. Asymmetric binding of transferrin receptor to parvovirus capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6585–6589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hall GS, Little DP. 2007. Relative quantitation of virus population size in mixed genotype infections using sequencing chromatograms. J. Virol. Methods 146:22–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hueffer K, et al. 2003. The natural host range shift and subsequent evolution of canine parvovirus resulted from virus-specific binding to the canine transferrin receptor. J. Virol. 77:1718–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kwok PY, Carlson C, Yager TD, Ankener W, Nickerson DA. 1994. Comparative analysis of human DNA variations by fluorescence-based sequencing of PCR products. Genomics 23:138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Llamas-Saiz AL, et al. 1996. Structural analysis of a mutation in canine parvovirus which controls antigenicity and host range. Virology 225:65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson CD, et al. 2008. Detecting small changes and additional peptides in the canine parvovirus capsid structure. J. Virol. 82:10397–10407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palermo LM, Hueffer K, Parrish CR. 2003. Residues in the apical domain of the feline and canine transferrin receptors control host-specific binding and cell infection of canine and feline parvoviruses. J. Virol. 77:8915–8923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parker JS, Murphy WJ, Wang D, O'Brien SJ, Parrish CR. 2001. Canine and feline parvoviruses can use human or feline transferrin receptors to bind, enter, and infect cells. J. Virol. 75:3896–3902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parker JS, Parrish CR. 1997. Canine parvovirus host range is determined by the specific conformation of an additional region of the capsid. J. Virol. 71:9214–9222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parrish CR. 1991. Mapping specific functions in the capsid structure of canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus using infectious plasmid clones. Virology 183:195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parrish CR, Aquadro CF, Carmichael LE. 1988. Canine host range and a specific epitope map along with variant sequences in the capsid protein gene of canine parvovirus and related feline, mink and raccoon parvoviruses. Virology 166:293–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parrish CR, Carmichael LE. 1983. Antigenic structure and variation of canine parvovirus type-2, feline panleukopenia virus, and mink enteritis virus. Virology 129:401–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parrish CR, Carmichael LE. 1986. Characterization and recombination mapping of an antigenic and host range mutation of canine parvovirus. Virology 148:121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parrish CR, Carmichael LE, Antczak DF. 1982. Antigenic relationships between canine parvovirus type-2, feline panleukopenia virus and mink enteritis virus using conventional antisera and monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 72:267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parrish CR, et al. 1988. The global spread and replacement of canine parvovirus strains. J. Gen. Virol. 69(Pt 5):1111–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parrish CR, O'Connell PH, Evermann JF, Carmichael LE. 1985. Natural variation of canine parvovirus. Science 230:1046–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shackelton LA, Parrish CR, Truyen U, Holmes EC. 2005. High rate of viral evolution associated with the emergence of carnivore parvovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:379–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi W-F, et al. 2009. Selection pressure on haemagglutinin genes of H9N2 influenza viruses from different hosts. Virol. Sinica 24:65–70 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simpson AA, et al. 2000. Host range and variability of calcium binding by surface loops in the capsids of canine and feline parvoviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 300:597–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strassheim ML, Gruenberg A, Veijalainen P, Sgro JY, Parrish CR. 1994. Two dominant neutralizing antigenic determinants of canine parvovirus are found on the threefold spike of the virus capsid. Virology 198:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suzuki Y. 2005. Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 28:399–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Truyen U, Evermann JF, Vieler E, Parrish CR. 1996. Evolution of canine parvovirus involved loss and gain of feline host range. Virology 215:186–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Truyen U, Parrish CR. 1992. Canine and feline host ranges of canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus: distinct host cell tropisms of each virus in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 66:5399–5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsao J, et al. 1991. The three-dimensional structure of canine parvovirus and its functional implications. Science 251:1456–1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Volkov I, Pepin KM, Lloyd-Smith JO, Banavar JR, Grenfell BT. 2010. Synthesizing within-host and population-level selective pressures on viral populations: the impact of adaptive immunity on viral immune escape. J. R. Soc. Interface 7:1311–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weaver SC. 2006. Evolutionary influences in arboviral disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 299:285–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weinreich DM, Delaney NF, Depristo MA, Hartl DL. 2006. Darwinian evolution can follow only very few mutational paths to fitter proteins. Science 312:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilkening S, et al. 2005. Determination of allele frequency in pooled DNA: comparison of three PCR-based methods. Biotechniques 39:853–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xie Q, Chapman MS. 1996. Canine parvovirus capsid structure, analyzed at 2.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 264:497–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ye X, McLeod S, Elfick D, Dekkers JC, Lamont SJ. 2006. Rapid identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms and estimation of allele frequencies using sequence traces from DNA pools. Poult. Sci. 85:1165–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeung DE, et al. 1991. Monoclonal antibodies to the major nonstructural nuclear protein of minute virus of mice. Virology 181:35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]