Abstract

In this study, we investigated the role of damage to the nasal mucosa in the shedding of prions into nasal samples as a pathway for prion transmission. Here, we demonstrate that prions can replicate to high levels in the olfactory sensory epithelium (OSE) in hamsters and that induction of apoptosis in olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) in the OSE resulted in sloughing off of the OSE from nasal turbinates into the lumen of the nasal airway. In the absence of nasotoxic treatment, olfactory marker protein (OMP), which is specific for ORNs, was not detected in nasal lavage samples. However, after nasotoxic treatment that leads to apoptosis of ORNs, both OMP and prion proteins were present in nasal lavage samples. The cellular debris that was released from the OSE into the lumen of the nasal airway was positive for both OMP and the disease-specific isoform of the prion protein, PrPSc. By using the real-time quaking-induced conversion assay to quantify prions, a 100- to 1,000-fold increase in prion seeding activity was observed in nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic treatment. Since neurons replicate prions to higher levels than other cell types and ORNs are the most environmentally exposed neurons, we propose that an increase in ORN apoptosis or damage to the nasal mucosa in a host with a preexisting prion infection of the OSE could lead to a substantial increase in the release of prion infectivity into nasal samples. This mechanism of prion shedding from the olfactory mucosa could contribute to prion transmission.

INTRODUCTION

The presence of prion infectivity in bodily fluids and secretions has been proposed to be a source for prion transmission (10, 31, 32, 37, 41, 48, 50, 55). Breast milk from scrapie-infected ewes is the only secretion that has been linked to vertical transmission (36, 38). Placenta from prion-infected sheep or carcasses from deer and elk that succumb to chronic wasting disease in nature are likely to be important sources of environmental contamination (48, 50). However, horizontal transmission either directly through contact with infected hosts or indirectly through contamination of the environment has not been linked to any specific source of prion infectivity despite its role in transmission of chronic wasting disease in cervids and scrapie in sheep (27, 42). Low prion titers are found in blood, saliva, urine, and feces from prion-infected ruminants and rodents (18, 31, 32, 55), and although one or more of these sources could be involved in prion transmission, none of them has yet to be directly implicated in natural prion transmission. In addition, the disease-specific prion protein, PrPSc, is below the level of detection in these bodily fluids by standard immunoassays but, in some cases, can be detected using PrPSc seeding-based amplification assays (13, 31, 40, 46).

An alternate hypothesis states that olfactory neurons in the nasal mucosa are a potential source of prion infection through the release of prions into nasal secretions (10, 17, 63). Since neurons replicate prions to significantly higher levels than other cell types, the prion titer in nasal fluids has the potential to be substantially greater than those in other bodily fluids in which prions are shed from nonneuronal cells. Prion infectivity and PrPSc deposits in neurons and nerve bundles in the peripheral and central olfactory systems are found in both human prion disease and natural prion diseases of ruminants (4, 15, 17, 29, 30, 39, 63). In an experimental prion infection of hamsters, the primary site of infection in the nasal mucosa is the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs), whose cell bodies and dendrites are located within the olfactory sensory epithelium (OSE) (10, 17). The total prion titer of nasal mucosa extracts was reported previously to be only ∼100-fold less than the level of prion infectivity in the olfactory bulb (10). It was proposed that centrifugal spread of the prion agent from the central nervous system to the peripheral ORNs via the olfactory nerve resulted in high prion titers in the nasal mucosa because of the high number of neurons in the OSE (10). Furthermore, the previous studies demonstrated low-to-moderate levels of prion infectivity in lavage samples from the nasal cavity, which could be due to the localization of PrPSc to the terminal dendrites of ORNs at the border with the lumen of the nasal airway (10). Another mechanism of prion shedding from the nasal mucosa could be the continual turnover and replacement of ORNs throughout adult life (12, 23), since mature ORNs survive for approximately 30 to 40 days before undergoing apoptosis (28, 44). It has been proposed that prion-infected ORNs could release PrPSc into nasal secretions following apoptosis and serve as a source of prion infectivity for prion transmission (10, 17, 63).

ORNs are also the most environmentally exposed subset of neurons, but despite nasotoxic insults, olfaction is maintained through the regenerative capacity of ORN progenitor cells and cellular mechanisms to resist environmental stress. However, many environment-borne pathogens, toxins, and chemicals can induce apoptosis of ORNs, leading to hyposmia or anosmia. Those insults that can induce apoptosis in ORNs include viruses, bacteria, fungi, bacterial cell wall components, mycotoxins, allergies, man-made chemicals dispersed in the environment, and tobacco smoke (3, 16, 22, 24, 25, 34, 43, 57, 61). Since encounters with these biological and environmental nasotoxic insults can occur often and multiple times, we investigated whether an increase in apoptosis of ORNs or damage to the OSE in a prion-infected host could increase the amount of prion infectivity released into nasal fluids. In the present study, infection of the OSE was established in hamsters infected with the hyper strain (HY) of the transmissible mink encephalopathy (TME) agent and acute sloughing of the OSE from nasal turbinates was observed after induction of apoptosis in ORNs. Analysis of olfactory marker protein (OMP), a protein found only in ORNs (58), and the cellular and disease-specific isoforms of the prion proteins (PrPC and PrPSc, respectively) revealed that these proteins were released from the nasal mucosa into the lumen of the nasal cavity for several days after nasotoxic injury. A rapid, highly sensitive, and quantitative prion seeding assay was used to measure the amount of prion agent in olfactory tissues and nasal lavage samples, and it revealed a 100- to 1,000-fold increase in prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury. These studies demonstrate that damage to the nasal mucosa results in a significant increase in the release of prion infectivity into the lumen of the nasal airway and suggest that conditions that induce apoptosis in ORNs or that disrupt the olfactory epithelium in prion-infected hosts can lead to accelerated prion shedding from the nasal cavity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal inoculations and tissue collection.

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Montana State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (47); these guidelines were established by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and approved by the Governing Board of the U.S. National Research Council. Weanling, Syrian golden hamsters (Simonsen Laboratories, Gilroy, CA) were inoculated in the olfactory bulb with 2 μl of a brain homogenate from a normal hamster (i.e., from the mock-infected group) or from a HY TME agent-infected hamster containing 108.5 intracerebral lethal median doses per ml as described previously (7, 8). For intraolfactory bulb inoculations, a minor surgical procedure was performed as described previously (10). Following inoculation with the HY TME agent, hamsters were observed at least three times per week for the onset of clinical symptoms, which include hyperesthesia, tremors of the head and trunk, and ataxia. Animals were euthanized after the onset of clinical symptoms of HY TME.

Methimazole can induce apoptosis in ORNs, and this effect is dose and time dependent (26). To determine the appropriate dose of methimazole to disrupt the OSE in hamsters, groups of animals (n = 3) were intraperitoneally inoculated with different doses of methimazole (0, 100, 125, 150, and 300 mg/kg of body weight) and tissues were collected for histological analysis at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h posttreatment. Based on hematoxylin and eosin analysis of the OSE, it was determined that a dose of 125 mg/kg methimazole was the minimal dose that consistently resulted in at least a 50% disruption of the OSE by 48 h after methimazole treatment.

After the onset of clinical symptoms of HY TME, nasal lavage samples were collected from the mock-infected and HY TME groups every 24 h for five consecutive days. These samples are designated the 0-, 24-, 48-, 72-, and 96-h nasal lavage samples. For nasotoxic treatment, hamsters were intraperitoneally inoculated with vehicle alone or methimazole at 125 mg/kg in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Vehicle and methimazole treatment was administered after collection of nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point. After the 96-h collection time, hamsters were euthanized and the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate were removed and stored at −80°C. A modification of this experimental design included vehicle and methimazole treatment after collection of the nasal lavage sample at time zero and two additional nasal lavage sample collections at 24 and 48 h. Nasal lavage samples were collected from hamsters anesthetized with isoflurane by inserting a blunt-end 25-gauge needle into the right nare, gently flushing with 2 ml of PBS, and collecting the PBS lavage fluid as it drained from the left nare. For collection of olfactory tissues for immunohistochemistry, hamsters from which nasal lavage samples were not collected were perfused with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde (PLP) fixative and tissues were dissected and processed for embedding in paraffin wax as described previously (5, 9, 17, 45).

Three separate trials were performed for the experimental design described above. A total of 16 mock-infected hamsters and 24 HY TME agent-infected hamsters were used for this study. For histological and immunohistochemical analyses, nine hamsters (three mock- and six HY TME agent-infected hamsters) were fixed with PLP, in addition to the hamsters used to optimize the methimazole dose as described above. For Western blot analysis of PrP and OMP, 31 hamsters (13 mock- and 18 HY TME agent-infected hamsters) were used to collect nasal lavage samples at 24-h intervals, and olfactory bulbs and nasal turbinates were also collected from these hamsters and frozen at −80°C until they were analyzed. Of the mock-infected hamsters, 3 were treated with vehicle only and 13 were treated with methimazole. For the HY TME hamsters, there were 8 in the vehicle group and 16 were treated with methimazole. For histological, immunohistochemical, and Western blot analyses, there was a minimum of three hamsters per group per treatment. For OMP and PrP Western blot analysis of hamsters treated with vehicle alone, four individual hamsters were analyzed, while in the methimazole treatment group a total of eight individual hamsters were analyzed (Table 1). For the real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) analysis of nasal lavage samples, a total of 68 samples were analyzed for the time to maximal thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, with three to five hamsters used for each time point (see Fig. 7). For measurement of the prion median seeding dose (SD50) in nasal lavage, olfactory bulb, and nasal turbinate samples, three mock- and three HY TME agent-infected hamsters were analyzed (Table 2).

Table 1.

Levels of olfactory marker protein and prion protein in the olfactory bulb, nasal turbinate, and nasal lavage samples by Western blot analysis

| Treatmenta | Infection type | Protein analyzedb | Relative signal intensityc in: |

Relative signal intensityc in nasal lavage (h): |

No. of trials | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory bulb | Nasal turbinate | 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | ||||

| Vehicle | Mock | OMP | 132 | 100 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| PrP | 130 | 100 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Vehicle | HY TME | OMP | 103 ± 2 | 100 | 2 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 3 |

| PrP | 176 ± 43 | 100 | 5 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 0 | 1 ± 1 | 3 | ||

| Methimazole | Mock | OMP | 142 ± 30 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 30 ± 11 | 36 ± 8 | 26 ± 10 | 3 |

| PrP | 223 | 100 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 27 | 51 | 2 | ||

| Methimazole | HY TME | OMP | 101 ± 19 | 100 | 0 | 1 ± 1 | 30 ± 8 | 30 ± 6 | 25 ± 12 | 5 |

| PrP | 302 ± 29 | 100 | 3 ± 1 | 1 ± 0 | 20 ± 6 | 37 ± 7 | 57 ± 15 | 6 | ||

Nasal lavage samples were collected at time zero and 24 h later. Immediately after the 24-h collection point, hamsters were intraperitoneally inoculated with methimazole (125 mg/kg) in PBS-DMSO or with vehicle alone. After treatment, nasal lavage samples were collected every 24 h at three additional collection points (i.e., 48, 72, and 96 h). The olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate were also collected at the 96-h time point.

For Western blot analysis of OMP, 50 μg of protein each was used for the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate extracts while for total PrP, between 10 and 50 μg of protein was analyzed. Analysis of nasal lavage samples was performed following precipitation of proteins from 200 μl at each time point. The intensity of Western blot signals was measured using Kodak 1D software.

The signal intensities for nasal turbinates were assigned a relative value of 100, and values for all the other samples were expressed as a percentage of 100. Mean percentages for OMP and PrP for each treatment group are indicated. For treatment groups with three or more trials, the standard error of the mean (SEM) is included.

Fig 7.

RT-QuIC assay of nasal lavage samples from HY TME hamsters. The time to maximum ThT fluorescence in the RT-QuIC assay was measured for nasal lavage samples collected every 24 h for five consecutive days from HY TME hamsters following treatment with vehicle only (open bars) or methimazole (closed bars), which was administered after the collection of nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point. Nasal lavage samples from three to five hamsters were assayed at each time point for both treatment groups. Samples that did not reach maximum ThT fluorescence by 63 h were not included in the analysis, but this set consisted only of samples from either the vehicle or pre-methimazole treatment group. At each collection point, the values for the vehicle and methimazole groups were compared using a paired t test (two-tailed). *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001.

Table 2.

PrPSc SD50 values in olfactory tissues from HY TME agent-infected hamsters

| Trial | Hamster group | Infection type | Total SD50a in nasal lavage (h): |

Treatmentb at h: |

Total SD50 in nasal lavage (h): |

Total SD50 at 48 h in: |

Total SD50 at 96 h in: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | Nasal turbinate | Olfactory bulb | Nasal turbinate | Olfactory bulb | |||

| 1 | H1635.3 | HY TME | <101.5 | 101.9 | Vehicle | 102.7 | 102.5 | 102.5 | 109.6 | 1010.9 | ||||

| H1635.4 | HY TME | 102.9 | 103.2 | Vehicle | 102.9 | 102.9 | 103.2 | 109.5 | 1010.8 | |||||

| H1636.3 | HY TME | 102.4 | <101.5 | Methimazole | 105.2 | 105.0 | 105.2 | 108.0 | 1010.3 | |||||

| H1636.4 | HY TME | 102.9 | 103.2 | Methimazole | 105.5 | 105.7 | 105.2 | 109.5 | 108.8 | |||||

| 2 | H1641.3 | Mock | <101.5 | Methimazole | <101.5 | <101.5 | <101.5 | <101.5 | ||||||

| H1644.3 | HY TME | 103.0 | Methimazole | 105.7 | 105.2 | 108.5 | 109.9 | |||||||

The SD50 was measured by endpoint dilution using the RT-QuIC assay and calculated by the Spearman-Kärber method (20). The total SD50 was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Each SD50 value is for a single hamster from which sequential nasal lavage samples were collected at the indicated time points.

Nasal lavage samples were collected at time zero and 24 h later in trial 1 and at time zero in trial 2. Immediately after the 0-h (trial 2) or 24-h (trial 1) collection point, hamsters were intraperitoneally injected with methimazole (125 mg/kg) in PBS-DMSO or with vehicle alone. After treatment, nasal lavage samples were collected every 24 h at two or three additional collection points (i.e., 48, 72, and 96 h). The olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate were also collected at the 48-h (trial 2) or 96-h (trial 1) time point.

Tissue homogenization, Western blot analysis, and immunohistochemistry.

Frozen olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate samples were prepared in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.5% Igepal) containing 1× complete protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) to approximately 10% (weight per volume). Tissues were homogenized using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY) with either glass beads (for olfactory bulb samples) or zirconium beads (for nasal turbinates). Nasal lavage samples were prepared by methanol precipitation of protein, and the pellets were resuspended in PBS. The protein concentrations in tissue homogenates and nasal lavage samples were measured using the micro-bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce Protein Research, Rockford, IL).

Western blot analysis was performed with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) NuPAGE gels (12% acrylamide; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and samples were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes as described previously (5). For analysis of OMP, 50 μg of protein from lysates of the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate tissues and 200 μl of nasal lavage fluid were used and OMP was detected with goat anti-OMP polyclonal antibody (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) as described previously (10). For detection of prion protein, between 10 and 50 μg of protein from olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate lysates and 200 μl of nasal lavage fluid were analyzed and immunodetection was performed with murine anti-PrP 3F4 monoclonal antibody as described previously (5, 9). Kodak 1D software (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY) was used to measure the OMP and prion protein signals on Western blots. Within an individual Western blot, the OMP and prion protein signals in the nasal turbinate were assigned a value of 100 and the levels of signal in the olfactory bulb and nasal lavage samples were reported relative to the 100 value. The mean value from several trials is reported in Table 1.

For Western blotting of caspase 3, 50 μg of protein from nasal turbinate lysates was analyzed on NuPAGE gels and immunodetection was performed with rabbit anti-caspase 3 polyclonal antibody (product no. 9662; Cell Signaling Technology) that detects both pro-caspase 3 and cleaved (cl)-caspase 3 (Asp175). Western blots were stripped and reprobed with rabbit antiactin polyclonal antibody. The apoptotic index was calculated by two approaches. One measured the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to total caspase 3 (cl-caspase 3 plus pro-caspase 3) and the second measured the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to actin within an individual sample. Kodak 1D software was used to quantify band intensity on Western blots. The values from individual hamsters (n = 3 per treatment group) were used to compare different treatments (e.g., vehicle and methimazole), and statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test (two-tailed). P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

For immunostaining, skulls containing the nasal cavity and olfactory bulb were collected after PLP fixation, decalcified, and embedded in paraffin wax and PrPSc and OMP immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were performed as described previously (5, 45). In addition, immunofluorescence analysis for cl-caspase 3 was performed using rabbit anti-cl-caspase 3 (Asp175) polyclonal antibody (product no. 9661; Cell Signaling Technology).

RT-QuIC assay of olfactory tissues.

For the RT-QuIC assay, olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate lysates were adjusted to a protein concentration of 1 μg per μl, while nasal lavage samples in PBS were not adjusted for protein concentration. The RT-QuIC assay was performed as described previously (59). Briefly, samples were preincubated in an equal volume of PBS containing 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and N2 medium supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 10 min. For dilution analysis, after preincubation the samples were serially diluted 10-fold in PBS containing 0.28% SDS and 0.56× N2 medium supplement to a final dilution of 10−11. An 8-μl aliquot of each sample dilution was used to seed each RT-QuIC reaction in a 96-well microtiter plate (a black plate with a clear bottom). Each RT-QuIC reaction mixture included RT-QuIC buffer (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 300 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA tetrasodium salt), 10 μM thioflavin T (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., Atlanta, GA), and hamster recombinant PrP 90-231 (0.1 mg/ml) (2, 59). All samples were analyzed in quadruplicate RT-QuIC reactions using a Fluostar Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC) at 42°C for 63 h. Two hundred fifty cycles (one cycle consists of shaking at 700 rpm for 1 min and resting for 1 min) were performed, and ThT fluorescence measurements were made every 15 min.

Spearman-Kärber analysis was used to calculate the prion SD50 per milliliter (for nasal lavage samples) or per microgram of protein (for olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate samples), and the SD50 was defined as the sample amount giving positive responses in 50% of replicate RT-QuIC reactions (20). Positive RT-QuIC reactions were designated as those with ThT fluorescence that was greater than 200% of the average ThT fluorescence signal for mock-infected samples. To calculate the total SD50, the SD50 per milliliter was multiplied by the total volume of the nasal lavage sample. For the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate, the total SD50 was calculated by multiplying the SD50 per microgram of protein by the total amount of protein (in micrograms) for each of the individual tissue lysates.

RESULTS

Nasotoxic injury induces apoptosis of ORNs, disrupts the integrity of the olfactory epithelium, and releases neuronal proteins into the nasal airway.

Prior studies demonstrated PrPSc deposition in the OSE of prion-infected animals and prion infectivity in lavage samples from the nasal cavity, suggesting that prion shedding into nasal secretions could have a role in prion transmission (10, 17, 35, 63). In order to investigate whether damage to the nasal epithelium can accelerate prion shedding from the nasal cavity, we induced apoptosis of ORNs in an animal model in which a preexisting prion infection had been established in the OSE. To induce damage to the OSE, hamsters were intraperitoneally inoculated with methimazole, a drug used for treatment of thyroid disorders that also can cause hyposmia, anosmia, and morphological changes to the nasal mucosa (26, 51). Methimazole is metabolized by a cytochrome P450-dependent pathway in duct cells of Bowman's gland, which are located in the subepithelial layer of the nasal mucosa, and leads to the induction of apoptosis in olfactory neurons and detachment of the nasal epithelium (6, 51). In the absence of methimazole treatment, the OSE remained intact and prominent immunostaining for OMP, a protein expressed in ORNs, was observed in ORNs in the OSE and in the nerve bundles of ORNs in the subepithelial layer (Fig. 1A and B; also data not shown). At 24 and 72 h after methimazole treatment, the majority of the OSE was stripped from the nasal turbinates while the subepithelial layer remained partially intact (Fig. 1C and D; also data not shown). OMP immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed a prominent signal in the nerve bundles of the subepithelial layer but an infrequent signal in the OSE since it was removed from the turbinates (Fig. 1F). Cellular debris was observed in the lumen of the nasal airway, and this was often positive by OMP IHC, indicating that ORNs were released into the lumen of the nasal airway (Fig. 1C, D, E, and F). Histological examination of the oral mucosa did not reveal disruption of the epithlelial mucosa or cellular changes following methimazole treatment, indicating that there were not systemic changes to mucosal surfaces (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Disruption of the olfactory sensory epithelium following nasotoxic injury. The nasal turbinates in the nasal cavity from mock-infected hamsters treated with vehicle only (A and B) or methimazole (C, D, E, and F) were analyzed for OMP by using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (A and C) and immunohistochemistry (brown) (B and D) at 24 h after treatment. (B) OMP is prominent in the OSE and nerve bundles (NB) in the subepithelial layer (SE) in the absence of methimazole treatment. (C and D) Following methimazole treatment, the OSE was observed to slough off the nasal turbinates (arrowhead in panel C), but OMP immunostaining was still observed in nerve bundles of the SE (D). Some OMP immunoreactivity was observed in cellular debris in the lumen of the nasal airway (arrowhead in panel D). In panels C and D, the labels E and F refer to areas that were enlarged and illustrated in panels E and F. NA, lumen of the nasal airway.

Evidence that methimazole causes apoptosis of ORNs was determined by analysis of cl-caspase 3, a terminal signal for apoptosis, in the OSE and extracts of the nasal turbinate. Western blotting for cl-caspase 3 and pro-caspase 3 in hamsters following vehicle treatment and 8, 16, and 24 h after methimazole treatment revealed an increase (P < 0.001; unpaired t test) in the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to total caspase 3 as well as an increase in the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to actin at the three time points posttreatment (Fig. 2). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that cl-caspase 3-positive cells were increased in the OSE of hamsters at 12 and 24 h after methimazole treatment compared to those in vehicle-treated hamsters (Fig. 3A and B). The location of the cl-caspase 3-positive cells in the OSE was consistent with distribution in ORNs, and these cells also had condensed nuclei, which is indicative of apoptosis-mediated cell death (data not shown). An increase in cl-caspase 3 immunofluorescence was also found in nerve bundles in the nasal turbinates; in the outer nerve layer of the olfactory bulb, containing mainly axons of ORNs; and in glomeruli of the olfactory bulb, which are synapse-rich structures containing nerve terminals of ORNs (Fig. 3C and D). Unlike the cl-caspase 3 immunofluorescence in the OSE, the pattern in the outer nerve layer and glomeruli of the olfactory bulb was not associated with distinct nuclei and is consistent with localization to axons and nerve terminals of the olfactory receptor neurons.

Fig 2.

Apoptotic index for nasal turbinates following methimazole treatment. The apoptotic index was measured as the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to total caspase 3 (A) and the ratio of cl-caspase 3 to actin (B) by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. Postmethimazole (post-MTz) is the time point in hours at which nasal turbinates were collected for cl-caspase 3, pro-caspase 3, and actin analyses after methimazole treatment. Asterisks indicate a P value of <0.001 (unpaired t test) for comparison of the vehicle group to each methimazole group.

Fig 3.

Distribution of cleaved caspase 3 following apoptosis of olfactory receptor neurons. Hamsters were treated with either vehicle alone (A) or methimazole (B, C, and D), and the nasal turbinates (A and B) and olfactory bulb (C and D) were collected 12 and 24 h following treatment for analysis of apoptosis by cleaved caspase 3 immunofluorescence (red). Cleaved caspase 3 was infrequent in the OSE and olfactory bulb samples from vehicle-treated hamsters (A and data not shown). Following methimazole treatment, cl-caspase 3 immunofluorescence was observed in the disrupted OSE (arrows in panel B) in a pattern consistent with deposition in ORNs, as well as in the outer nerve layer (ONL) and glomeruli (*) in the olfactory bulb (C and D). The ONL is composed of the axons of the ORNs, and the glomeruli are synapse-rich structures containing the nerve terminals of ORNs as well as dendrites from neurons in the olfactory bulb. An increase in cl-caspase 3 in the OSE, ONL, and glomeruli is consistent with apoptosis of ORNs following methimazole treatment. Nuclei are stained with ToPro 3 (blue). SE, subepithelial layer; NA, lumen of the nasal airway. Scale bars, 50 μm.

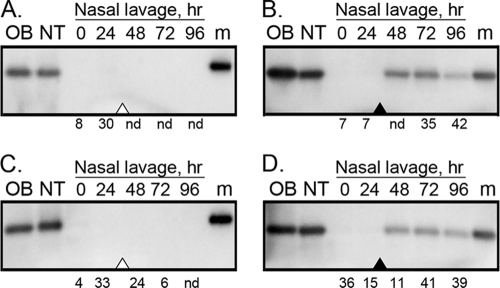

To further investigate the release of ORNs into the nasal airway following methimazole-induced apoptosis of ORNs, nasal lavage samples were collected prior to and following methimazole treatment and analyzed for OMP by Western blotting. In the first study, nasal lavage samples were collected from age-matched, mock- and clinically HY TME agent-infected hamsters for five consecutive days at 24-h intervals (0- to 96-h time points). After the 24-h collection point, hamsters were treated with vehicle alone, and after the 96-h collection point, animals were culled and the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate were collected. Western blotting revealed OMP in lysates of the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate, but OMP was undetectable in all of the nasal lavage samples from the mock- and HY TME agent-infected groups (Fig. 4A and C). This experiment was repeated, but now hamsters were treated with methimazole to induce apoptosis of ORNs after collection of the nasal lavage sample at the 24-h time point. As in the case of vehicle treatment, OMP was found in the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate lysates and was absent from nasal lavage samples at the 0- and 24-h collection points for mock- and HY TME agent-infected hamsters. However, OMP was now present in nasal lavage samples from the 48-, 72-, and 96-h collection points for both the mock- and HY TME agent-infected groups (Fig. 4B and D). This finding indicates that methimazole treatment resulted in the release of OMP-positive ORNs from the OSE into the lumen of the nasal airway within 24 h and that this release extended to at least 72 h posttreatment. A semiquantitative analysis of the OMP signal in Western blots revealed that in the absence of methimazole treatment the OMP signal in the olfactory bulb ranged from levels equivalent to those in the nasal turbinate up to 1.3-fold greater than those in the nasal turbinate but that the OMP signal in the nasal lavage samples was <5% of the OMP signal in the nasal turbinate (Table 1). Following methimazole treatment, the OMP ratio between the olfactory bulb and the nasal turbinate did not change. However, in nasal lavage samples after methimazole treatment (i.e., at the 24-h collection point), the OMP levels consistently ranged between 25 and 35% of the OMP signal in the nasal turbinate for both the mock- and HY TME agent-infected groups at the 48- through 96-h collection points (Table 1). Prior to methimazole treatment (i.e., at the 0- and 24-h collection points), the percentage of OMP in the nasal lavage samples was <5% of that in the nasal turbinate. These findings demonstrate that there was a significant increase in the amount of OMP released into the lumen of the nasal airway after nasotoxic treatment that causes apoptosis of ORNs and suggest that sloughing of the ORNs from the OSE results in release of neuronal proteins into nasal fluids.

Fig 4.

Western blots for OMP in olfactory tissues and nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury. Age-matched mock-infected (A and B) and HY TME agent-infected (C and D) hamsters were treated with vehicle only (A and C) or methimazole (B and D) after the collection of nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point (open and filled arrowheads, respectively). Nasal lavage samples were collected every 24 h for five consecutive days, and after the 96-h collection point, the olfactory bulb (OB) and nasal turbinate (NT) were also collected for OMP analysis. Fifty micrograms of protein for the OB and NT lysates and 200 μl of nasal lavage fluid were analyzed by Western blotting using polyclonal anti-OMP goat antibody. The total amount of protein in nasal lavage samples varied from below the level of detection (i.e., <1 μg/ml) to 70 μg protein. The value under each nasal lavage lane indicates the total amount of protein (in micrograms) analyzed. Nd refers to none detected and indicates levels below the limit of detection. The marker (m) lane contains a polypeptide at 20 kDa.

Nasotoxic injury that induces apoptosis of ORNs removes prion proteins from the olfactory epithelium and releases them into the nasal airway.

To determine the fate of PrPC and PrPSc in the olfactory system following an increase in ORN apoptosis and disruption of the OSE, these studies were extended to investigate the prion protein distributions in olfactory tissues and nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury. For these studies, the nasal mucosae of mock- and HY TME agent-infected groups were analyzed for OSE tissue morphology and PrPSc deposition in the absence or presence of methimazole treatment, similar to the studies represented in Fig. 1. In the mock- and HY TME agent-infected groups, the OSE remained intact and OMP was prominent in the OSE and subepithelial layers at 72 h following vehicle treatment (Fig. 5A, C, G, and I). However, after methimazole treatment OMP was found primarily in nerve bundles of the subepithelilal layer since under these conditions the OSE was disrupted and partially stripped from the turbinates (Fig. 5D, F, J, and L). OMP-positive cellular debris was also observed in the lumen of the nasal airway following methimazole treatment (Fig. 5, arrows). PrPSc immunofluorescence did not reveal PrPSc deposition in the OSE of vehicle- or methimazole-treated mock-infected hamsters (Fig. 5B and E). Among HY TME agent-infected hamsters, a punctate PrPSc deposition pattern was observed in the OSE in vehicle-treated hamsters (Fig. 5H and I), and at a higher magnification, PrPSc deposits were localized to the OMP-positive cell bodies and dendrites of ORNs (Fig. 5I, inset). PrPSc deposits were infrequently observed in nerve bundles in the subepithelial layer of the nasal turbinates in HY TME hamsters. However, following methimazole treatment of HY TME hamsters, PrPSc was not readily found in the OSE but PrPSc was occasionally found in sloughed cellular debris in the lumen of the nasal airway (Fig. 5K and L). Methimazole-induced apoptosis of ORNs and disruption of the OSE was consistent with a loss of PrPSc in the nasal mucosa of HY TME hamsters.

Fig 5.

Distribution of OMP and PrPSc following disruption of the olfactory sensory epithelium. The olfactory sensory epithelium in the nasal cavity from mock-infected (A to F) and HY TME agent-infected (G to L) hamsters was analyzed by laser scanning confocal microscopy for OMP (red) (A, D, G, and J), PrPSc (green) (B, E, H, and K), and for both OMP and PrPSc (C, F, I, and L). Panels A through C, D through F, G through I, and J through L show the same fields of view. Hamsters were treated either with vehicle alone (A to C and G to I) or with methimazole (D to F and J to L) and analyzed 72 h after treatment. OMP is present in olfactory receptor neurons, and immunofluorescence was observed in the OSE (the white bar indicates the width of the OSE) and nerve bundles (*) in the vehicle-treated group and primarily in the nerve bundles following methimazole treatment. OMP immunofluorescence in the OSE was less frequent following methimazole treatment and disruption of the OSE, but it could be observed separating from the epithelium (arrow in panels D, F, J, and L) and in the lumen of the nasal airway (NA). PrPSc was not observed in mock-infected hamsters but was present in the OSE of HY TME hamsters in the vehicle group (H) and in the disrupted OSE of the methimazole-treated HY TME hamsters (arrow in panels K and L). The nuclei (blue) of olfactory receptor neurons are packed at a high density in the OSE of the vehicle-treated groups. Scale bar, 50 μm.

A biochemical analysis of PrPC and PrPSc in the olfactory system also revealed a redistribution of these molecules upon nasotoxic injury and an increase in apoptosis of ORNs. In findings similar to our results for OMP in the nasal cavity, PrPC in mock-infected hamsters and total PrP (i.e., the sum of PrPC and PrPSc) in clinically HY TME agent-infected hamsters were detected in the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate lysates but not in the nasal lavage samples from vehicle-treated hamsters (Fig. 6A and C). Quantification of the prion protein signal in Western blots indicated that the levels in the olfactory bulb lysates were 1.3- to 1.7-fold higher than those in the nasal turbinate lysates but that the PrP levels in the nasal lavage samples were ≤5% of those in the nasal turbinates (Table 1). Following methimazole treatment (after collection of the nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point), PrPC and total PrP were observed in the nasal lavage samples at the 48-, 72-, and 96-h time points (Fig. 6B and D). Quantification of the PrP signal revealed that the levels in the nasal lavage samples at these three time points ranged between 10 and 57% of those found in the nasal turbinates and that there was a stepwise increase in PrP levels with each consecutive nasal lavage fluid collection point (Table 1). The increased prion protein levels found in nasal lavage samples from clinically HY TME agent-infected hamsters compared to mock-infected hamsters following nasotoxic injury could reflect the increased levels of total prion protein found in the nasal turbinate lysates of HY TME hamsters (Fig. 6B versus D). The PrPC and PrPSc migration pattern in nasal lavage samples also appears distinct from that for the olfactory bulb-derived prion proteins. The 27-kDa PrP protein that predominates in the nasal lavage samples from HY TME hamsters was described previously to be a PrPSc isoform found in the nasal turbinate and is distinct from brain PrPSc (10), which has three major PrPSc polypeptides. These findings demonstrate that apoptosis of ORNs induced by nasotoxic injury results in an increase in the release of prion proteins into the lumen of the nasal airway.

Fig 6.

Western blots for prion protein in olfactory tissues and nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury. Age-matched mock-infected (A and B) and HY TME agent-infected (C and D) hamsters were treated with vehicle only (A and C) or methimazole (B and D) after the collection of nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point (open and filled arrowheads, respectively). Nasal lavage samples were collected every 24 h for five consecutive days, and after the 96-h collection point, the olfactory bulb (OB) and nasal turbinate (NT) were also collected for PrP analysis. For the OB and NT lysates, 10 μg (B and D), 12.5 μg (C), or 50 μg (A) of protein was analyzed while for the nasal lavage samples 200 μl was analyzed by Western blotting using monoclonal anti-PrP 3F4 mouse antibody. The total amount of protein in nasal lavage samples varied from below the level of detection (i.e., <1 μg/ml) to 70 μg protein. The marker (m) lane contains polypeptides at 20, 30, and 40 kDa.

Prion activity in nasal lavage samples increases up to 1,000-fold after increased apoptosis of ORNs due to nasotoxic injury.

To estimate the relative amounts of prion infectivity in olfactory tissues and nasal lavage samples, we used a quantitative prion seeding assay called RT-QuIC. Previous studies demonstrated that RT-QulC seeding activity correlates strongly with the presence of prions (59). Both RT-QulC prion seeding activity and prion infectivity (as detected by animal bioassays) can be measured by endpoint dilution analyses to determine 50% seeding doses (SD50) and median lethal doses (LD50), respectively. The RT-QuIC assay is a rapid, highly sensitive, and quantitative method to measure prions that is based on the ability of PrPSc to alter the conformation of recombinant PrP so that it can bind to ThT, which is a fluorescent molecule that binds specifically to amyloid proteins. An additional RT-QuIC analysis, determination of the time to maximum ThT fluorescence (i.e., the length of time to reach saturation of the fluorescent signal), was used for assessing the relative amount of prion seeding activity. There is an inverse correlation between the amount of prion seeding activity and the time to maximum ThT fluorescence. When the time to maximum ThT fluorescence decreases, this indicates that there is an increase in the prion seeding activity. When the time to maximum ThT fluorescence was used to measure prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples from five consecutive collections at 24-h intervals from vehicle-treated HY TME agent-infected hamsters (n = 6), there was no difference among the nasal lavage samples (Fig. 7). The mean times ranged between 34 and 39 h, which was consistent with samples with low-to-moderate levels of prion infectivity. These findings indicate that similar levels of prion seeding activity were recovered at each consecutive time point. When HY TME hamsters (n = 6) were treated with methimazole after collection of nasal lavage samples at the 24-h time point, there was a significant reduction in the time to maximal ThT fluorescence in the RT-QuIC assay, from 30 to 37 h at the 0- and 24-h time points to 21 to 23 h at the 48- to 96-h time points (Fig. 7). This higher level of prion seeding activity was consistent with a higher level of PrPSc in nasal lavage samples following an increase in apoptosis of ORNs in HY TME hamsters following nasotoxic injury (Fig. 6D and Table 1).

In a second trial, methimazole treatment of HY TME hamsters (n = 4) resulted in a >40% reduction in the time to maximum ThT fluorescence, from 31 h for both the 0- and 24-h time points prior to methimazole treatment to 18 h or less at the 48- to 96-h time points after methimazole treatment (data not shown). In both of these trials, 34 nasal lavage samples from mock-infected hamsters were assayed in quadruplicate and partial seeding activity was found in one or two replicates from only two samples. Upon retesting of these samples, both were negative (data not shown). These findings indicate that there were consistent levels of prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples from HY TME hamsters that were collected over a several-day period and that there was an increase in prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury. These experimental results were consistent with a reduction of PrPSc in the OSE detected by IHC and an increase in the amount of prion protein in nasal lavage samples detected by Western blotting after an increase in apoptosis of ORNs following nasotoxic injury.

The RT-QuIC assay was also used to measure the prion seeding activity, or the SD50, of the olfactory bulb, nasal turbinate, and nasal lavage samples in the absence and presence of nasotoxic injury. The total SD50 was defined as (i) the SD50 per milliliter in a nasal lavage sample, multiplied by the total volume of the nasal lavage sample, or (ii) the SD50 per microgram of protein in an olfactory bulb or nasal turbinate lysate, multiplied by the total micrograms of protein in the olfactory bulb or nasal turbinate lysate. The total SD50 values of nasal lavage samples collected over five consecutive days from vehicle-treated HY TME hamsters ranged from <101.5 to 103.2, but for an individual hamster the SD50 values of the consecutive nasal lavage samples were within 101, excluding samples in which no prion seeding activity could be measured (Table 2, H1635.3 and H1635.4). Similar total SD50 values were measured in nasal lavage samples from HY TME hamsters at the 0- and 24-h collection points prior to nasotoxic injury (Table 2, H1636.3 and H1636.4). Among nasal lavage samples collected from four individual hamsters either without or prior to nasotoxic injury, 11 of 14 samples had a total SD50 between 102.9 and 103.2, which illustrates that the amount of prions recovered in nasal lavage samples was consistent over this time period. After methimazole treatment, the total SD50 in nasal lavage samples at the 48-h through 96-h time points was 100- to 1,000-fold higher than in nasal lavage samples prior to treatment (Table 2, H1636.3 and H1636.4; Fig. 8). The total SD50 in nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury was between 105.0 and 105.7 for six of six nasal lavage samples collected from two individual hamsters. Much higher total SD50 values were found in the olfactory bulb and nasal turbinate lysates (as high as 1010.9 and 109.6, respectively) from both vehicle- and methimazole-treated HY TME hamsters (Table 2). In three of four HY TME agent-infected hamsters, the total SD50 in the olfactory bulb was 10- to 100-fold greater than that in the nasal turbinate. In a second trial, prion seeding activity was not detected in olfactory tissue and nasal lavage samples from a mock-infected hamster while the total SD50 values for a HY TME agent-infected hamster before and after methimazole treatment were consistent with the results of the first trial. The nasal lavage sample collected prior to methimazole treatment had a total SD50 of 103.0, and after methimazole treatment the total SD50 was 100- to 1,000-fold higher in each of two additional nasal lavage samples (Table 2). These findings indicate that there were low-to-moderate levels of prion infectivity in nasal lavage samples before nasotoxic injury and that there was a significant increase in the release of prion infectivity into nasal lavage samples following nasotoxic injury to the OSE that caused apoptosis of ORNs.

Fig 8.

RT-QuIC assay of olfactory tissues from HY TME agent-infected hamsters. The RT-QuIC assay was used to measure ThT fluorescence for a duration of 63 h in individual reactions seeded with serial dilutions of olfactory bulb samples (A), nasal turbinate samples (B), nasal lavage samples from the 0-h collection point (T0) (C), and nasal lavage samples from the 48-h collection point (T48; 24 h after methimazole treatment) (D). Samples were assayed neat and serially diluted 10-fold (10-f) to 1,000-fold (1K-f), 1,000,000-fold (1 M-f), and 1,000,000,000-fold (1B-f). Normal hamster brain (NBH) was used as a negative control and 100 fg of PrPSc from a 263K scrapie strain-infected hamster brain was used as a positive control in the RT-QuIC assay. Four replicate wells were assayed for each sample, and each data point on the curve is the average of results for replicates. The corresponding median prion seeding dose (SD50) for these tissues (H1636.3) can be found in Table 2. Panels representative of results from the RT-QuIC assay are shown.

DISCUSSION

The release or shedding of prions from an infected host is an important pathway of horizontal prion transmission, and the ability to establish infection in a naive host is strongly dependent on the infectious dose upon exposure. Although multiple sources of bodily fluids are likely to contribute to disease transmission, the findings of the present studies demonstrate that ORNs can be a source for the shedding of higher doses of prion agent than previously reported for other secretions. There are several findings to support a role for ORNs and damage to the OSE in the shedding of prions from an infected host. First, the olfactory system is a common target for prion infection in several natural and experimental prion infections, and PrPSc has been found in the OSE, ORNs, and/or the olfactory nerve (4, 10, 15, 17, 29, 30, 39, 63). Second, ORNs undergo continual turnover and programmed cell death, or apoptosis, throughout adult life (12, 23). It is conceivable that apoptosis of prion-infected ORNs could release prion infectivity into nasal fluids, especially since there is evidence for PrPSc deposition in terminal dendrites of ORNs that project into the mucus layer. ORNs are also the most environmentally exposed subset of neurons, and there are many types of environmental factors that can cause stress to ORNs and induce apoptosis (3, 16, 22, 24, 25, 34, 43, 57, 61). An increase in ORN apoptosis can also disrupt the mucosal integrity of the OSE and cause a sloughing off of cells into the nasal airway. In this study, we demonstrate that inducing apoptosis of ORNs in a prion-infected host resulted in immunodetection of PrPSc in nasal lavage samples and a 100- to 1,000-fold increase in prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples.

In bodily fluids and mucosal surfaces of prion-infected hosts, the levels of PrPSc and/or prion infectivity are low compared to those in nasal fluids, extracts of nasal turbinates, and the OSE. Immunodetection of PrPSc has not been observed in urine, saliva, feces, blood, or breast milk from rodents and ruminants with prion infection (31, 38, 46, 55), but PrPSc can be detected using serial protein misfolding cyclic amplification (sPMCA) (31, 40, 46), which can amplify the level of PrPSc by >109-fold so that it can be detected by Western blotting. Alternatively, the enhanced QuIC assay, a modification of the RT-QuIC assay, can rapidly measure low levels of prion seeding activity in blood samples (49). The prion infectivity levels in these fluids, when reported, are also very low (18, 31, 38). Despite the small amounts of infectious prions in most bodily fluids, saliva from deer with CWD has been used to transmit CWD following experimental oral exposure of deer (41). Breast milk from sheep with scrapie can also transmit disease to lambs, indicating that this is a natural route of vertical transmission, although the source is not certain since PrPSc was not observed in mammary tissues of sheep with scrapie that had an otherwise normal health status (36, 38). In the present study, methimazole-induced apoptosis of ORNs resulted in the release of prion protein that could readily be detected in nasal fluids by Western blotting. This is a significant finding in light of previous studies that were unable to detect PrPSc in other bodily fluids from prion-infected hosts that have been implicated in prion transmission. The level of prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples after methimazole treatment was between 103 and 105 SD50 below the prion activity in the olfactory bulb. Previous studies demonstrate that the prion titer in the olfactory bulb is comparable to that in a HY TME agent-infected brain, or ∼109.5 LD50 per gram of tissue (7, 10). A comparison of the SD50 and LD50 using the RT-QuIC assay and an animal bioassay, respectively, with brain homogenates infected with the 263K scrapie strain illustrated similar sensitivities of these methods (59). Based on these studies, we estimate the amount of prion infectivity in nasal lavage samples after methimazole treatment to be approximately 104.5 to 106.5 LD50 in a 2-ml lavage sample. We estimate that during collection of nasal lavage samples that we dilute nasal secretions by approximately 100- to 1,000-fold. Therefore, we propose that a high concentration of prions (i.e., >107.5 LD50 per ml) can be released in nasal secretions following damage to the nasal mucosa in a host with prion infection of the OSE.

Additional evidence for nasal fluids as a potential source for new prion infections is based on our findings that there is a high level of prion infection in the nasal mucosa and previous studies that demonstrated PrPSc deposition in ORNs and the olfactory nerve in natural and experimental prion diseases (10, 15, 17, 63). In HY TME agent infection in hamsters, the amount of PrPSc in extracts of the nasal mucosa was within 2-fold of the level in the olfactory bulb on a per protein basis in the absence of methimazole treatment, and the prion median seeding activity in these extracts was only 10- to 100-fold below the levels found in the olfactory bulb. In one hamster, the total SD50 was 10-fold higher in the nasal turbinate than in the olfactory bulb. The slightly lower levels of PrPSc and prion seeding activity in the nasal mucosa than in the olfactory bulb indicate that the OSE also can support high levels of prion replication. These findings are consistent with natural prion diseases in sheep with scrapie in which the relative amount of PrPSc in the olfactory turbinates was ∼10% of the level present in the brain. This is further evidence that high levels of PrPSc and prion infectivity are present in the olfactory mucosa in both natural and experimental prion diseases (15).

The targeting of prion infection to the nasal mucosa is due likely to the presence of an estimated 20 million olfactory receptor neurons in the OSE (in hamsters, for example), which is greater than the number of neurons estimated to be in the entire olfactory bulb (11, 52). These high levels of PrPSc and prion infectivity in the nasal mucosa have not been detected at the surfaces of other mucosal sites and are due likely to the distinct neuroanatomy of the olfactory system in which the axons of the ORNs (i.e., the olfactory nerve) project into the olfactory bulb, where they synapse with mitral and tufted cells in the synapse-rich glomeruli (14). This pathway is the likely route of prion agent spread from the central nervous system to the OSE and ORNs (10). PrPSc deposition in the soma of ORNs and along the border of the OSE with the lumen of the nasal airway suggests that prions are in direct contact with nasal fluids. This targeting of prion infection to ORNs could lead to release of prion infectivity due to the normal turnover of ORNs and/or sloughing off of the OSE into the lumen of the nasal airway due to environmental factors.

In the present study, increasing apoptosis of ORNs and damage to the nasal mucosa in a prion-infected host resulted in loss of the OSE, sloughing of the OSE into the lumen of the nasal airway, and an increase in OMP and prion proteins as well as prion seeding activity in nasal lavage samples. These findings indicate that significant levels of prion infectivity can be released upon disruption of the nasal mucosa. There are many insults that are able to induce apoptosis of ORNs (1, 19, 21, 25, 33, 53, 54, 56, 61, 62), and in a natural prion infection these could promote prion agent release into nasal fluids. These factors include influenza A virus infection, in which virus-infected ORNs undergo apoptosis and, if the ORNs are prion infected, rhinitis and sneezing associated with flu symptoms could promote dissemination of prions into the environment (43). Other ubiquitous microorganisms and potential pathogens or agents that can induce apoptosis of ORNs include Staphylococcus aureus and Aspergillus fumigatus, as well as the common bacterial cell wall component lipopolysaccharide (22, 25, 61). Molds produce mycotoxins that can induce apoptosis of ORNs, and man-made chemicals present in the environment such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) can break down into chlorinated hydrocarbons that also can induce apoptosis of ORNs (3, 24). Other conditions can cause disruption of the nasal mucosa or induce necrosis of ORNs. The most common are those that cause rhinosinusitis, including allergies, chronic illness, and other inflammatory conditions in the nasal cavity (1, 19, 21, 56, 60, 62). ORNs appear to have a unique niche among neurons in adults since they normally undergo apoptosis and are exposed to biological and environmental insults that shorten their life span. These features of ORNs along with their ability to replicate prions also make them a good candidate for releasing high levels of prion infectivity into nasal fluids upon damage, which can directly expose susceptible hosts and can contaminate the environment with prion agent.

In this study, we demonstrate that high levels of prion infection can be established in the nasal mucosa and that substantial amounts of PrPSc and prion seeding activity can be released into nasal secretions following an increase in apoptosis of ORNs and disruption of the OSE. These findings have several implications: (i) nasal secretions from prion-infected hosts could serve as a source of new prion infections, either directly through contact with susceptible hosts or indirectly through contamination of the environment; (ii) common insults to ORNs or the nasal mucosa of a prion-infected host could accelerate release of prion infectivity into nasal secretions; and (iii) nasal fluids may provide a noninvasive approach for diagnosis of prion infection using the highly sensitive and quantitative RT-QuIC assay, perhaps in combination with a procedure that induces partial shedding of the OSE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01 AI055043, R21 AI084094, and P20 RR020185 from the National Institutes of Health, the National Research Initiative of the USDA CSREES grant 2006-35201-16626, and the Murphy Foundation. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

We thank the staff at the Montana State University Animal Resource Center, especially Renee Arens, for excellent animal care.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Apter AJ, Gent JF, Frank ME. 1999. Fluctuating olfactory sensitivity and distorted odor perception in allergic rhinitis. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 125:1005–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atarashi R, et al. 2008. Simplified ultrasensitive prion detection by recombinant PrP conversion with shaking. Nat. Methods 5:211–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bahrami F, van Hezik C, Bergman A, Brandt I. 2000. Target cells for methylsulphonyl-2,6-dichlorobenzene in the olfactory mucosa in mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 128:97–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balkema-Buschmann A, et al. 2011. BSE infectivity in the absence of detectable PrP(Sc) accumulation in the tongue and nasal mucosa of terminally diseased cattle. J. Gen. Virol. 92:467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartz JC, Kincaid AE, Bessen RA. 2003. Rapid prion neuroinvasion following tongue infection. J. Virol. 77:583–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergman U, Brittebo EB. 1999. Methimazole toxicity in rodents: covalent binding in the olfactory mucosa and detection of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the olfactory bulb. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 155:190–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bessen RA, Marsh RF. 1994. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 68:7859–7868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bessen RA, Marsh RF. 1992. Identification of two biologically distinct strains of transmissible mink encephalopathy in hamsters. J. Gen. Virol. 73:329–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bessen RA, Martinka S, Kelly J, Gonzalez D. 2009. Role of the lymphoreticular system in prion neuroinvasion from the oral and nasal mucosa. J. Virol. 83:6435–6445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bessen RA, et al. 2010. Prion shedding from olfactory neurons into nasal secretions. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bonthius DJ, Bonthius NE, Napper RM, West JR. 1992. Early postnatal alcohol exposure acutely and permanently reduces the number of granule cells and mitral cells in the rat olfactory bulb: a stereological study. J. Comp. Neurol. 324:557–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carr VM, Farbman AI. 1992. Ablation of the olfactory bulb up-regulates the rate of neurogenesis and induces precocious cell death in olfactory epithelium. Exp. Neurol. 115:55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Castilla J, Saa P, Soto C. 2005. Detection of prions in blood. Nat. Med. 11:982–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen WR, Shepherd GM. 2005. The olfactory glomerulus: a cortical module with specific functions. J. Neurocytol. 34:353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corona C, et al. 2009. Olfactory system involvement in natural scrapie disease. J. Virol. 83:3657–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corps KN, Islam Z, Pestka JJ, Harkema JR. 2010. Neurotoxic, inflammatory, and mucosecretory responses in the nasal airways of mice repeatedly exposed to the macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxin roridin A: dose-response and persistence of injury. Toxicol. Pathol. 38:429–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeJoia C, Moreaux B, O'Connell K, Bessen RA. 2006. Prion infection of oral and nasal mucosa. J. Virol. 80:4546–4556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diringer H. 1984. Sustained viremia in experimental hamster scrapie. Brief report. Arch. Virol. 82:105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doty RL, Mishra A. 2001. Olfaction and its alteration by nasal obstruction, rhinitis, and rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 111:409–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dougherty R. 1964. Animal virus titration techniques, p 183–186. In Harris R. (ed), Techniques in experimental virology. Academic Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duncan HJ, Seiden AM. 1995. Long-term follow-up of olfactory loss secondary to head trauma and upper respiratory tract infection. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 121:1183–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Epstein VA, Bryce PJ, Conley DB, Kern RC, Robinson AM. 2008. Intranasal Aspergillus fumigatus exposure induces eosinophilic inflammation and olfactory sensory neuron cell death in mice. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 138:334–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farbman AI. 1990. Olfactory neurogenesis: genetic or environmental controls? Trends Neurosci. 13:362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franzen A, Carlsson C, Brandt I, Brittebo EB. 2003. Isomer-specific bioactivation and toxicity of dichlorophenyl methylsulphone in rat olfactory mucosa. Toxicol. Pathol. 31:364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ge Y, Tsukatani T, Nishimura T, Furukawa M, Miwa T. 2002. Cell death of olfactory receptor neurons in a rat with nasosinusitis infected artificially with Staphylococcus. Chem. Senses 27:521–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Genter MB, Deamer NJ, Blake BL, Wesley DS, Levi PE. 1995. Olfactory toxicity of methimazole: dose-response and structure-activity studies and characterization of flavin-containing monooxygenase activity in the Long-Evans rat olfactory mucosa. Toxicol. Pathol. 23:477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Georgsson G, Sigurdarson S, Brown P. 2006. Infectious agent of sheep scrapie may persist in the environment for at least 16 years. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3737–3740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Graziadei PP, Graziadei GA. 1979. Neurogenesis and neuron regeneration in the olfactory system of mammals. I. Morphological aspects of differentiation and structural organization of the olfactory sensory neurons. J. Neurocytol. 8:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hadlow WJ, et al. 1974. Course of experimental scrapie virus infection in the goat. J. Infect. Dis. 129:559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hadlow WJ, Kennedy RC, Race RE. 1982. Natural infection of Suffolk sheep with scrapie virus. J. Infect. Dis. 146:657–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haley NJ, Seelig DM, Zabel MD, Telling GC, Hoover EA. 2009. Detection of CWD prions in urine and saliva of deer by transgenic mouse bioassay. PLoS One 4:e4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunter N, et al. 2002. Transmission of prion diseases by blood transfusion. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2897–2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ibanes JD, Morgan KT, Burleson GR. 1996. Histopathological changes in the upper respiratory tract of F344 rats following infection with a rat-adapted influenza virus. Vet. Pathol. 33:412–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Islam Z, Harkema JR, Pestka JJ. 2006. Satratoxin G from the black mold Stachybotrys chartarum evokes olfactory sensory neuron loss and inflammation in the murine nose and brain. Environ. Health Perspect. 114:1099–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kincaid AE, Bartz JC. 2007. The nasal cavity is a route for prion infection in hamsters. J. Virol. 81:4482–4491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Konold T, Moore SJ, Bellworthy SJ, Simmons HA. 2008. Evidence of scrapie transmission via milk. BMC Vet. Res. 4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kruger D, et al. 2009. Faecal shedding, alimentary clearance and intestinal spread of prions in hamsters fed with scrapie. Vet. Res. 40:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lacroux C, et al. 2008. Prions in milk from ewes incubating natural scrapie. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee YH, et al. 2009. Detection of pathologic prion protein in the olfactory bulb of natural and experimental bovine spongiform encephalopathy affected cattle in Great Britain. Vet. Pathol. 46:59–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maddison BC, et al. 2009. Prions are secreted in milk from clinically normal scrapie-exposed sheep. J. Virol. 83:8293–8296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mathiason CK, et al. 2006. Infectious prions in the saliva and blood of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science 314:133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller MW, Williams ES, Hobbs NT, Wolfe LL. 2004. Environmental sources of prion transmission in mule deer. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1003–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mori I, et al. 2002. Olfactory receptor neurons prevent dissemination of neurovirulent influenza A virus into the brain by undergoing virus-induced apoptosis. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2109–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moulton DG. 1974. Dynamics of cell populations in the olfactory epithelium. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 237:52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mulcahy ER, Bartz JC, Kincaid AE, Bessen RA. 2004. Prion infection of skeletal muscle cells and papillae in the tongue. J. Virol. 78:6792–6798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murayama Y, et al. 2007. Urinary excretion and blood level of prions in scrapie-infected hamsters. J. Gen. Virol. 88:2890–2898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Research Council 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 48. Onodera T, Ikeda T, Muramatsu Y, Shinagawa M. 1993. Isolation of scrapie agent from the placenta of sheep with natural scrapie in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 37:311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Orru CD, et al. 2011. Prion disease blood test using immunoprecipitation and improved quaking-induced conversion. mBio 2:e00078–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Race R, Jenny A, Sutton D. 1998. Scrapie infectivity and proteinase K-resistant prion protein in sheep placenta, brain, spleen, and lymph node: implications for transmission and antemortem diagnosis. J. Infect. Dis. 178:949–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sakamoto T, Kondo K, Kashio A, Suzukawa K, Yamasoba T. 2007. Methimazole-induced cell death in rat olfactory receptor neurons occurs via apoptosis triggered through mitochondrial cytochrome c-mediated caspase-3 activation pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 85:548–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schoenfeld TA, Knott TK. 2004. Evidence for the disproportionate mapping of olfactory airspace onto the main olfactory bulb of the hamster. J. Comp. Neurol. 476:186–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwob JE, Saha S, Youngentob SL, Jubelt B. 2001. Intranasal inoculation with the olfactory bulb line variant of mouse hepatitis virus causes extensive destruction of the olfactory bulb and accelerated turnover of neurons in the olfactory epithelium of mice. Chem. Senses 26:937–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sumner D. 1964. Post-traumatic anosmia. Brain 87:107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tamguney G, et al. 2009. Asymptomatic deer excrete infectious prions in faeces. Nature 461:529–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vent J, et al. 2004. Pathology of the olfactory epithelium: smoking and ethanol exposure. Laryngoscope 114:1383–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wagner JG, Hotchkiss JA, Harkema JR. 2002. Enhancement of nasal inflammatory and epithelial responses after ozone and allergen coexposure in Brown Norway rats. Toxicol. Sci. 67:284–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walters E, et al. 1996. Proximal regions of the olfactory marker protein gene promoter direct olfactory neuron-specific expression in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 43:146–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilham JM, et al. 2010. Rapid end-point quantitation of prion seeding activity with sensitivity comparable to bioassays. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Winther B, Gwaltney JM, Jr., Mygind N, Hendley JO. 1998. Viral-induced rhinitis. Am. J. Rhinol. 12:17–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yagi S, et al. 2007. Lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis of olfactory receptor neurons in rats. Acta Otolaryngol. 127:748–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yee KK, et al. 2010. Neuropathology of the olfactory mucosa in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 24:110–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zanusso G, et al. 2003. Detection of pathologic prion protein in the olfactory epithelium in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:711–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]