Abstract

Herpesviruses establish latency in suitable cells of the host organism after a primary lytic infection. Subgroup C strains of herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), a primate gamma-2 herpesvirus, are able to transform human and other primate T lymphocytes to stable growth in vitro. The viral genomes persist as nonintegrated, circular, and histone-associated episomes in the nuclei of those latently infected T cells. Epigenetic modifications of episomes are essential to restrict the transcription during latency to selected viral genes, such as the viral oncogenes stpC/tip and the orf73/LANA. In this study, we describe a genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation-on-chip (ChIP-on-chip) analysis to profile the occupancy of CTCF on the latent HVS genome. We then focused on two distinct, conserved CTCF binding sites (CBS) within the orf73/LANA promoter region. Analysis of recombinant viruses harboring deletions or mutations within the CBS indicated that the lytic replication of such viruses is not substantially influenced by CTCF. However, T cells latently infected with CBS mutants were impaired in their proliferation abilities and showed a significantly reduced episomal maintenance. We detected a reduced transcription of the orf73/LANA gene in the T cells, corresponding to the reduced viral genomes; this might contribute to the loss of HVS episomes, as LANA is central in the maintenance of viral episomes in the dividing T cell populations. These data demonstrate that the episomal stability of HVS genomes in latently infected human T cells is dependent on CTCF.

INTRODUCTION

Herpesviruses establish a lifelong persistence within the nuclei of a defined subset of host cells. Multiple copies of the viral genome are maintained as extrachromosomal, nonintegrating circular episomes that have acquired cellular histones to form regular nucleosome-like structures (10, 38). The expression of most viral genes is shut down during latency, which enables the virus to escape from the host immune surveillance. Epigenetic modifications and chromatin structure of the herpesviral genome play a critical role in the establishment and maintenance of the latent infection. Complex strategies have evolved for maintenance of the herpesvirus genomes within host cells, including the ability to replicate and segregate in a bidirectional manner synchronously with cellular DNA and segregate to daughter cells (36). Specific herpesviral proteins such as Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) or latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated human herpesvirus 8 (KSHV) are thought to mediate efficient segregation of the episome. They attach the viral genomes to host chromosomes, preventing their loss during mitosis (24, 35). Moreover, the viral genome has different gene expression programs at its disposal, thereby representing another level of virus-host interaction that integrates cellular growth and differentiation signals with viral gene expression and chromatin organization. Gene expression in eukaryotic cells is highly regulated at multiple distinct levels. Epigenetic modifications of DNA and the associated histones, as well as compartmentalization shielding of one type of chromatin from adjacent regions, are key to transcriptional regulation and to the inheritance of gene expression patterns.

Herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), the prototypic gamma-2 herpesvirus, is a T-lymphotropic herpesvirus and closely related to KSHV. Neither the acute infection nor the lifelong persistence in T lymphocytes is known to cause disease in its natural host, the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus). However, rapidly growing T cell malignancies can be observed after experimental infection of other susceptible New World primates, like common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) and cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus) (16). HVS can be classified into three subgroups (A, B, C) due to differences in gene content and oncogenic potential (29). Viruses of subgroup C, like strain C488, are considered the most oncogenic and are able to transform human T cells to antigen-independent growth (4). The HVS C488 genome comprises approximately 155-kb double-stranded DNA and harbors at least 77 open reading frames (ORF). The coding, AT-rich low-density L-DNA is 113 kb in size and flanked by noncoding repetitive DNA elements of the high-density H-DNA (14).

Multiple copies of the intact viral genomes are maintained within the HVS transformed human T cells in a state of tightly controlled latency, and no secretion of viral particles occurs (39). The bicistronic transcript of orf1 is consistently detectable and encodes the StpC (Saimiri transformation-associated protein of subgroup C) and Tip (tyrosine-kinase interacting protein). Both gene products are oncoproteins and are essential for the transformation of T lymphocytes (11). Moreover, four transcripts from viral URNA genes are detectable; however, these are dispensable for growth in vitro (12). The orf73 encoding LANA is expressed at low levels (14). Analogous to its counterparts LANA in KSHV and EBNA1 in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), orf73 tethers the viral episome to metaphase chromosomes during cell division and thereby ensures efficient segregation of the HVS genome (6, 48). Additionally, the LANA protein is involved in the suppression of the lytic replication cascade (37). During the last couple of years, it has become clear that epigenetic processes on herpesviral episomes are central to organize the complex regulatory mechanisms of latency. It has been shown for all herpesvirus subgroups that episomes are rapidly chromatinized with histones in the nuclei of infected cells (33, 44) and distinct and dynamic histone modification patterns can be observed upon stimulation of latent herpesviral genomes with chemicals like butyrate or tricostatin A (TSA) (2, 47).

The establishment of chromatin boundaries, the prevention of heterochromatic spreading and enhancer blocking activities are essential elements for the organization of complex genetic loci. A protein prominently involved in the three-dimensional organization of chromatin is the multifunctional, DNA-binding factor CTCF. This highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed nuclear phosphoprotein assembles at a wide diversity of 50-bp DNA elements within cellular and viral genomes, which are free of DNA methylation (30). Initially, it was found to be involved in transcriptional repression of avian, mouse, and human myc promoters (31). Moreover, enhancer blocking activity, chromatin insulation, and imprinting on diverse gene loci have been attributed to CTCF function (49, 52). CTCF is also able to shield chromatin domains with different modification and transcription patterns by binding to insulator elements. As a consequence, the spreading of euchromatin or heterochromatin and therefore a deregulated expression or the silencing of genes is inhibited (54). CTCF is able to dimerize or oligomerize, thereby interacting with other CTCF proteins at distant regions on the same or even on a different chromosome (27, 40). Due to this intrachromosomal interaction, the DNA is organized into loops (22, 41, 53). The CTCF-mediated interchromosomal interaction brings elements of different chromosomes into close proximity and even enables the regulation of genes in trans (51). Involvement of CTCF in epigenetic regulation of viral replication has already been shown for different herpesviruses. In herpes simplex virus 1, binding of CTCF to a region between the LAT enhancer and the transcriptional end of ICP0 accounts for the different chromatin domains and for the insulation of the LAT enhancer activity from the ICP0 promoter (3, 8). Moreover, CTCF acts as a boundary factor for the latent cycle gene expression programs of Epstein-Barr virus (7, 43). More recent studies have implicated that cohesins, which have a highly similar consensus DNA binding sequence, are involved in CTCF function (32, 50). It was shown for latent KSHV that cohesins colocalize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and that such binding sites are essential for clonal stability and repression of lytic cycle gene products (42). Moreover, CTCF and cohesin interactions are involved in the cell cycle control of KSHV latency transcription (21).

In this study, we wanted to investigate if CTCF binding sites (CBS) are present in the HVS genome. With the generation of recombinant viruses harboring mutations or deletions of CBS, we sought to gain more insight in the functional relevance of CTCF sites in herpesvirus genomes, during lytic replication or during the state of latency of HVS in human T cells. This is of particular importance, since this is the first report demonstrating the influence of CTCF binding on herpesviral latency in transformed cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, viruses, and plasmid transfections.

HEK293T cells and owl monkey kidney cells (OMKs) were cultivated in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum. Transfections were performed when cells were approximately 80% confluent using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The HVS strain employed in this study was obtained by reconstitution of infectious viruses using Bac43MOD containing the genomic sequence of HSV strain C488 analogous to an earlier description (46). Stocks of wild type and recombinant viruses were prepared, and the amount of viral genomes in the supernatant of infected OMKs was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of the major capsid protein (MCP) locus (primers described below).

Primary human cord blood lymphocytes (CBLs) from different donors were infected and transformed with the different recombinant viruses (wild type [wt], mutant, and revertant). Maintenance of CBLs has been previously described (20). Noninfected control cells that were cultivated in parallel usually ceased growing after 3 to 6 weeks; the infected CBLs were cultivated further on and were considered transformed after 8 weeks of continuous expansion. For growth curve analysis, CBLs were counted before splitting using a Z2 cell counter (Beckman Coulter) and the overall amount of CBLs was calculated by multiplying the amount of cells counted with the number of splits to this date.

Oligonucleotide pulldown.

Purified genomic HVS DNA was used as template for PCR to generate biotin-labeled DNA for fragments upstream of orf73 (nucleotides 107134 to 107324, 107285 to 107475, 107450 to 107600, 107533 to 107724, and 107324 to 107724). HVS coordinates correspond to the genome sequence of C488 (14). A total of 20 μl HEK293T nuclear extract was incubated in a total amount of 200 μl containing 20 μl 10× band shift buffer (BSB) (5% Nonidet P40, 500 mM potassium chloride, 100 mM Tris hydrochloride [Tris-HCl; pH 7.5]), 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 100 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), 10 μg poly deoxyinosinic-deoxycytidylic acid [poly(dI-dC)] (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) for 10 min on ice. Afterwards, equimolar amounts of biotinylated DNA were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Streptavidin Sepharose (GE Healthcare) and 500 μl 1× BSB were added and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Afterwards, Streptavidin Sepharose was sedimented and washed twice with ice-cold 1× BSB and once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without Ca2+/Mg2+. Subsequently, precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting.

Western blotting and antibodies.

OMK cells were lysed in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 1% aprotinin-leupeptin) at distinct time points posttransfection. Equal amounts of cell lysates (20 μg total protein) were separated by electrophoresis on SDS-10% polyacrylamide (acrylamide/bis-acrylamide ratio, 37.5:1) gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF) (Immobilon; Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany). The immobilized proteins were then probed with the following primary antibodies (from BD) and antisera (GenScript): anti-CTCF (mouse, catalog no. 612149), anti-orf50 (rabbit), anti-orf75 (rabbit), anti-orf57 (rabbit), anti-orf6 (rabbit), and anti-orf17 (rabbit). Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were obtained from Dako (Dako Deutschland GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). Peroxidase activity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using the Kodak Image Station 4000MM Pro camera, and protein expression was quantified using the AIDA image analyzer version 4.22 software (Raytest GmbH, Straubenhardt, Germany).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Cy5-labeled fragments either not harboring CBS consensus motifs (nucleotides 107134 to 107324 of HVS C488) or spanning across the two CBS (nucleotides 107285 to 107475 of HVS C488) were incubated with 1 μg of recombinant CTCF protein (kindly provided by P. Liebermann, The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA) for 20 min at room temperature in the presence of 1 μg poly(dI-dC). Samples were loaded onto native 5% polyacrylamide gels (37.5:1) and electrophoresed in 0.5× TBE (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]) at 200 V for 2 h. Gels were directly exposed on a Kodak Image Station 4000MM Pro camera (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany) with appropriate excitation (630 nm) and emission (700 nm) filters.

Plasmids and cloning.

Firefly luciferase reporter plasmids Luc-WT and Luc-delCBS for the orf73/orf74 promoter region were obtained by PCR amplification of the respective promoter sequences from HVS bacmid (wild type and delCBS), followed by insertion of the PCR fragments (in either direction) into the SmaI restriction site of the promoterless pGL3-Basic (Invitrogen). Oligonucleotide primers for the amplification of the promoter sequences were as follows: orf73prom, 5′-GAGAAGCTTTGCACTCAGAACGCAGAGTGT-3′ and 5′-GAGCTCGAGCTACTGAAGTCCAGCTTGACC-3′; orf74prom, 5′-GAGCTCGAGTGCACTCAGAACGCAGAGTGT-3′ and 5′-GAGAAGCTTCTACTGAAGTCCGCTTGACC-3′. The expression plasmids Luc-mut1CBS, Luc-mut2CBS were generated by site-directed PCR mutagenesis of the Luc-WT constructs using specific primer pairs: mut1CBS, 5′-ATTGGCCACGTGGCTAATATAGGC-3′ and 5′-CGGTATATTAGCCACGTGGCCAAT-3′; mut2CBS, 5′-GACCAAATAACGTGTTTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GACGTTTCGATATACGTTCTT-3′. Finally, Luc-mut1/2CBS was generated with primer pairs of mut2CBS using Luc-mut1CBS as template DNA. The correct insertion into the reporter gene constructs was verified by DNA sequencing of the PCR-derived fragments within the reporter constructs. The promoterless pGL3-Basic vector was used as negative transfection control.

Luciferase reporter assay.

HEK293 and OMK cells in 24-well plates were cotransfected with 0.08 μg renilla control plasmid and 0.32 μg of the respective promoter construct per well using a ratio of 0.75 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per 1 μg DNA. Cells were harvested by centrifugation 1 day posttransfection, washed with PBS, and resuspended in 400 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.8], 0.5 M DTT, 1% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol) for 30 min. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation for 5 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C. Firefly luciferase activities were determined in triplicates by adding 100 μl assay buffer (100 mM K3PO4, 15 mM MgSO4, 5 mM ATP) supplemented with 5 mM ATP and 0.1 mM DTT and 0.2 mM d-luciferin. Renilla luciferase activities were measured by adding 100 μl assay buffer (1.1 M NaCl, 2.2 mM Na2EDTA, 0.22 M KPO4 [pH 5.1]) supplemented with 1.43 μM coelenterazine. Detection of luciferase activities was carried out using a microplate luminometer (Orion II; Berthold Detection Systems, Pforzheim, Germany). Firefly luciferase relative light units (RLU) were then normalized to renilla luciferase.

ChIP analysis and SYBR green quantitative real-time PCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation from HVS transformed T lymphocytes was performed as previously described (1). The experiments were performed with specific polyclonal rabbit anti-CTCF serum (catalog no. 07-729; Upstate) or a control polyclonal rabbit serum. The following oligonucleotide primer pairs were used in SYBR green qPCR: IP orf73prom, 5′-GTGCTACTCACATTGAAAATCGAAACTTC-3′ and 5′-GGTTTAACATATGTTTTGCGGTTGC-3′; MYC, 5′-GCCATTACCGGTTCTCCATA-3′ and 5′-CAGGCGGTTCCTTAAAACAA-3′; IP orf1prom, 5′-GTGTTGCTCTTGTTAGCTGTTTCTTGTG-3′ and 5′-AGAGAAATGTGTCAGACAAGAAGTGGG-3′; IP orf72, 5′-CATATAGCTAAAAATTGGTTGCAGACTGG-3′ and 5′-GACTACAAACATTTCCAAAAGGGCC-3′; and IP H-DNA repeat in, 5′-TGACGGCTGCAAACTCTGGC-3′ and 5′-TGGGGACCTGAGGGTTTTGG-3′. Total recovery by ChIP varied between 0.02% and 0.15% of input DNA. PCR data were normalized to input values that were quantified in parallel for each experiment.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

Total cellular RNA was extracted from human CBL lines transformed with different HVS mutants (wt, mut1CBS, mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, delCBS, and respective revertants) or infected OMK cells (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 5) using the Total RNA Isolation System (Promega). First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the ThermoScript reverse transcriptase PCR system (Invitrogen) with random hexamer and oligo-dT primers. Quantitative PCR was carried out with an Applied Biosystems 7500 sequence detection system for 40 cycles of denaturing (95°C, 15s) and annealing/synthesis (60°C, 40s). Primer and probe sequences were as follows: HPRT1, 5′-CCTCCCATCTCCTTCATCAC-3′ and 5′-CATTATGCTGAGGATTTGGAAAGG-3′ and 5′-/5Cy5/TCGAGCAAGACGTTCAGTCCTGTC/3lAbRQSp/-3′; orf73sp: 5′-CAGAACGCAGAGTGTGCTTCCTTC-3′ and 5′-GAACTTGCATCTTAATTCATCCGCAG-3′ and 5′-/5Cy5/TCTTCGTTTGAGCACCATATTGAAAATCGAAACT/3lAbRQSp/-3′; orf74: 5′-GCACTTCCTCATGTGATGGTGACA-3′, 5′-TAGCTTTGTGCGTAGCTGCTCAGT-3′ and 5′-/56FAM/TTTCTTGCA/ZEN/TAGAGGAGTGGTGTGTTG/3lABkFQ/-3′. All were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, and Leuwen, Belgium) or Biomers (Ulm, Germany). The correct length of PCR fragments was additionally verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The mRNA levels of viral genes of interest were quantified in relation to those of the cellular HPRT1 gene.

Quantitative PCR.

OMK cells infected with HVS (MOI, 5) were harvested at indicated time points, washed, and pelleted (18,600 × g, 2 h, 4°C, Hettich Mikro 200R). Pellets were lysed in 1× PCR buffer containing 0,5% Tween 20 and 100 μg/ml proteinase K for 50 min 56°C and 10 min 95°C). A total of 5 μl of lysates were used for quantitative PCR of viral MCP (orf25) and cellular CCR5. Primers and probes were as follows: MCP_for, 5′-CCATTTGCCTGTGTTGAGAGTTAA-3′; MCP_rev, 5′-CTCATTACCAGACCCATGTTATGAA-3′; MCP_probe, 5′-/56-FAM/CTCCGAGAG/ZEN/AGCCTATCTGAGATGCCC/3lABkFQ/-3′; CCR5_for, 5′-TGGTCATCTGCTACTCGGGAAT-3′; CCR5_rev, 5′-GGTGTTCAGGAGAAGGACAATGTT-3′, 5′-/5Cy5/AGCCCTGTGCCTCTTCTTCTCATTTCG/3lAbRQsp/-3′.

Microarray design.

Custom genome-tiling microarrays with the capacity for 15,000 oligonucleotide probes were purchased (8 × 15K; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) as described earlier (2). The microarray was equipped with both the HVS coding region, which was covered by 60-mer oligonucleotides with a spacing of 20 bp, and the GC-rich H-DNA repeats, which were covered by 45-mer oligonucleotides, to account for the difference in hybridization temperature. The probes were elongated to 60 bp with an Agilent linker DNA sequence. Probes covering cellular 5′ coding regions as well as promoter regions of housekeeping genes and probes from known CTCF binding sites represented the controls for CTCF binding. The probes were synthesized using the phosphoramidite method and printed onto the microarray with Agilent SurePrint technology in a randomized manner.

DNA amplification and microarray hybridization for ChIP-on-chip experiments.

DNA amplification of ChIP material for microarray hybridizations was performed as described earlier (2), using a protocol adapted from NimbleGen. The experimental CTCF-associated DNA samples were labeled with Cy5 dye, and the total input amplicons were labeled with Cy3 dye by ImaGenes GmbH (Berlin) and then cohybridized to Agilent 15K oligonucleotide tiling arrays. The CTCF ChIP signal was compared to control input signal, and the data were extracted according to standard operating procedures and visualized with SignalMap software (version 1.9; NimbleGen/Roche).

Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) mutagenesis.

The HVS Bac43MOD clone was used for recombination-mediated genetic engineering. A two-step λred-mediated recombination strategy (45) was employed for the construction of CBS recombinants. In the first step, an aphAI gene conferring resistance to the aminoglycoside antibiotic kanamycin is introduced; this is then specifically eliminated in a second recombination event facilitated by l-arabinose inducible I-SceI homing endonuclease, resulting in a markerless recombination product leaving behind nothing but the desired mutations or deletions. PCRs were performed with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes), DpnI was added to digest the template, and the amplification product was purified from an agarose gel with the NucleoBond gel extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Primers used for the manipulations are listed below. In order to accomplish the homologous recombination, the PCR fragment was then transformed into Escherichia coli strain GS1783 (gift of Gregory A. Smith, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), already harboring Bac43MOD, and Red recombination was performed. Cells were then plated on agar plates containing 15 μg/μl kanamycin (first recombination) or 15 μg/μl chloramphenicol and 1% l-arabinose (second recombination) and incubated at 32°C for 1 to 2 days. Bacterial colonies appearing on these plates were subjected to further characterization by restriction enzyme digest, PCR analyses, and direct sequencing of recombined junctions (see below). Reconstitution of recombinant HVS using purified bacmid DNA was performed as described previously (46). Oligonucleotides (Ultramer; IDT) used for homologous recombination in E. coli were as follows: Mut1CBS_for, 5′-TAGATGGCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAAACTATGCAATGATTGGTACCTCAGTACCTAATATAGGCATGAAACATAACATGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut1CBS_rev, 5′-CTGTGACCAACTTGTAAAAAATGTTATGTTTCATGCCTATATTAGGTACTGAGGTACCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAACAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; Mut2CBS_for, 5′-TTCGTTTGAGCACCATCTATAATTGCAACAAACACGTTATTTGGTCGACGTTCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut2CBS_rev, 5′-TGGCCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAAAGAACGTATATCGAACGTCGACCAAATAACGTGTTTGTTGCAATTCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; Mut1/2CBS_for, 5′-GGTCGACGTTCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAAACTATGCAATGATTGGTACCTCAGTACCTAATATAGGCATGAAACATAACATGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut1/2CBS_rev, 5′-CTGTGACCAACTTGTAAAAAATGTTATGTTTCATGCCTATATTAGGTACTGAGGTACCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAACAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; delCBS_for, 5′-TTCGTTTGAGCACCATCTATAATTGCAACAAACACGTTATCTAATATAGGCATGAAACATAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; delCBS_rev, 5′-ACCAACTTGTAAAAAATGTTATGTTTCATGCCTATATTAGATAACGTGTTTGTTGCAATTCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; Mut1CBS_Rev_for, 5′-TAGATGGCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAAACTATGCAATGATTGGCCACTAGGTGGCTAATATAGGCATGAAACATAACATGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut1CBS_Rev_rev, 5′-CTGTGACCAACTTGTAAAAAATGTTATGTTTCATGCCTATATTAGCCACCTAGTGGCCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAACAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; Mut2CBS_Rev_for, 5′-TTCGTTTGAGCACCATCTATAATTGCAACAAACACGTTATACACTAGATGGCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut2CBS_Rev_rev, 5′-TGGCCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAAAGAACGTATATCGCCATCTAGTGTATAACGTGTTTGTTGCAATTCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′; Mut1/2CBS/delCBS_Rev_for, 5′-TTTCTTCGTTTGAGCACCATCTATAATTGCAACAAACACGTTATACACTAGATGGCGATATACGTTCTTTCAAAAAACTATGCAATGATTGGCCGGATGACGACGATAAGTAGGG-3′; Mut1/2CBS/delCBS_Rev_rev, 5′-CTGTGACCAACTTGTAAAAAATGTTATGTTTCATGCCTATATTAGCCACCTAGTGGCCAATCATTGCATAGTTTTTTGAAAGAACGTATATCGCCAACCAATTAACCAATTCTGATTAG-3′.

Viral nucleic acid isolation and analysis.

Bacmid DNA was isolated by standard small scale alkaline lysis from 5 ml liquid cultures in LB medium. Subsequently, the integrity of bacmid DNA was analyzed by digestions with restriction enzyme XhoI and separation by 0.8% agarose pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in 0.5× TBE buffer using a Bio-Rad CHEF-DR III system at 6 V/cm, 120 degrees, 1 to 10 s switch time for 16 h at 14°C. For a characterization of insertion or deletion of the aphAI selection marker, recombinant bacmids were analyzed by PCR with primer pairs 5′-ATTCTGTTGGTGCTGCTTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GCTACGTCTGAGGAGGAGCTTAATT-3′, resulting in the amplification of the CBS cluster region either harboring the aphAI cassette or without this selection marker gene, respectively. Moreover, the nucleotide sequence of the CBS cluster region was determined by automated sequence analysis on an 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) in order to confirm the correct insertion of intended mutations, deletions, or revertant (wild-type) sequences as well as to exclude the presence of accidental mutations within the recombined region of the bacmid DNA.

RESULTS

Potential binding sites of CTCF at the orf73/orf74 intergenic region.

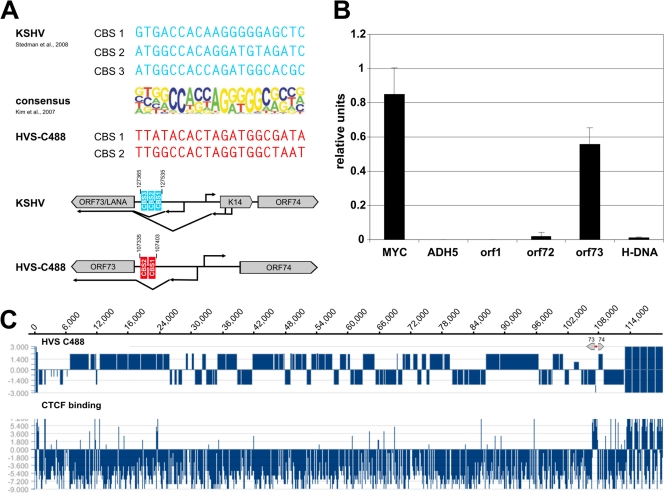

The HVS orf73 promoter region has been shown to comprise both heterochromatic and euchromatic histone modification marks (1, 2). Therefore, the question arose whether a chromatin border might be located in this region. When we compared the CTCF consensus binding sequence published by Kim and colleagues (23) with the HVS strain C488 genome sequence, two potential CTCF binding sites (CBS) were detected at the intergenic region of orf73/orf74, in the intron of the spliced orf73/LANA transcript. Additional references came from a study in KSHV, where three CBS have been identified at the corresponding homologous region to the HVS orf73 promoter (42) (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we performed chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments with HVS-transformed human CBLs and detected CTCF binding at the predicted sites. ChIP assays of control regions either showed specific binding of CTCF to the c-myc positive-control gene locus (18) or detected no significant enrichment of CTCF bound within the ADH5 negative-control region (Fig. 1B). Moreover, neither the neighboring regions of orf73 (orf72 promoter and H-DNA) nor the distant stpC/tip promoter did reveal binding of CTCF. Thus, three independent ChIP experiments demonstrated a strong, specific signal for the enrichment of CTCF to the intergenic region of orf73/orf74 (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

Detection of putative CTCF binding sites within the intergenic region of HVS orf73/orf74. (A) Schematic comparison of published CBS within the intergenic regions of KSHV orf73/K14 (AJ410493; blue) and potential CBS at HVS orf73/orf74 (KSU756098; red) to the consensus binding sequence of CTCF (23). (B) ChIP analysis of CTCF binding to the intergenic region of HVS orf73/orf74 (exemplary analysis by B. Alberter). Viral genomes from HVS transformed human CBLs were analyzed in three independent ChIP experiments using an anti-CTCF serum (rabbit) and subsequent SYBR green PCR. Mean values were calculated for each of the three data sets, and the mean values of the single experiments were then normalized to form a combined mean value (= 1). CBS of the myc gene locus served as positive control and the first intron of the cellular ADH5 gene represents the negative control. Further coding regions of HVS (orf1 promoter region, orf72 and H-DNA) were analyzed in addition to the putative CBS at the intergenic region of orf73/orf74. (C) ChIP-on-Chip analysis of CTCF binding to the latent HVS-C488 genome using a custom oligonucleotide array (done by B. Alberter as described in reference 2). Upper panel: HVS strain C488 L-DNA containing the known 75 open reading frames and five H-DNA repeat units. The scale of the x axis corresponds to the genome position in base pairs. Lower panel: CTCF binding in the latent HVS genome. The ratio of Cy3-labeled input and Cy5-labeled ChIP probe signals along the genome are displayed using SignalMap version 1.9.

For a high-resolution analysis of CBS within the HVS genome, ChIP-on-chip analysis was carried out from HVS transformed human T cells. The chip included control probes from the human genome that consisted of sequences of already reported CBS which served as positive controls (data not shown). The ChIP-on-chip analysis validated that the most prominent binding of CTCF occurred in the intergenic region of orf73/orf74 (Fig. 1C). Signals indicating additional CBS were found toward the left end of the HVS L-DNA and at the promoter regions of orf6 and orf10. As the significance and function of those other potential CBS require further studies, this work focuses on the strong and conserved binding sites in the intergenic region of orf73/orf74.

Mapping of CBS to two distinct sequences within the intergenic region of orf73/orf74.

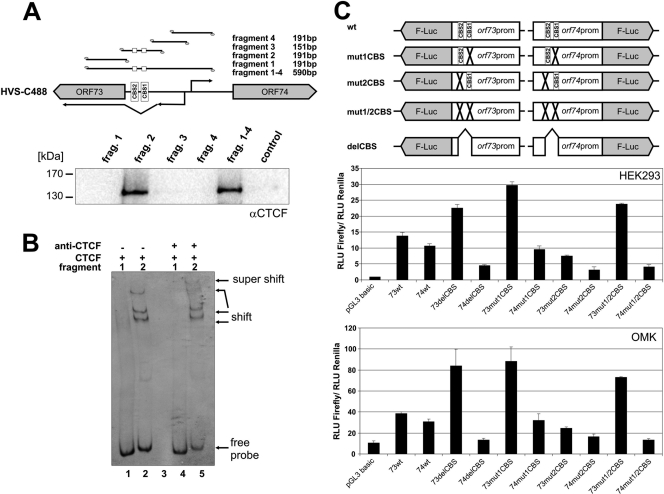

In order to further map and confirm the CBS, two additional experimental approaches were carried out (Fig. 2). First, we performed oligonucleotide pulldown assays with five distinct 5′-biotinylated DNA fragments overlapping the C-terminal region of the orf73/LANA gene and most parts of the intergenic region between orf73/orf74 (Fig. 2A, top panel). The two potential CBS were incorporated either in fragment 2 or the fragment spanning the full intergenic region (fragment 1–4). Using the nuclear protein fraction of HEK293T cells, we narrowed down and confirmed binding of CTCF to oligonucleotides 107335 to 107403 of HVS C488 of the intergenic region of orf73/orf74, since only fragment 2 or fragment 1–4 revealed CTCF binding by Western blotting (Fig. 2A, lower panel). Sequences adjacent to this region (fragment 1, 3, and 4) did not pull down a detectable amount of CTCF protein.

Fig 2.

CTCF binding to the HVS orf73/orf74 promoter region influences promoter activity. (A) Oligonucleotide pulldown with biotinylated DNA from HVS C488 region 107134 to 107724. HEK293T nuclear extract was incubated with biotinylated DNA fragments and bound proteins were identified by Western blotting with an antibody specific for CTCF. (B) Fluorescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with Cy5-labeled double-stranded DNA fragments encompassing fragment 1 or 2 (same fragments as in panel A), respectively. DNA fragments were incubated in the presence of recombinant CTCF protein (lanes 1 and 2) or in the presence of recombinant CTCF protein and a CTCF antibody (lanes 4 and 5) prior to gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments, fragment shifts, or supershifts were visualized by measuring the fluorescence signal. (C) Luciferase reporter assays. HEK293 cells or OMK cells were transfected with equal DNA amounts of empty vector pGL3 basic or one of the plasmids depicted in the upper scheme. A cotransfected renilla luciferase construct served as the internal standard for transfections. Luciferase assays were performed 1 day after transfection. Bars represent arithmetic means and standard deviations of luciferase activity normalized to renilla activity from three independent transfection experiments.

The CTCF binding was further analyzed by a fluorescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Fig. 2B). Cy5-labeled oligonucleotides, representing sequences and fragment 1 or 2 of the oligonucleotide pulldown assay (Fig. 2A, upper panel), were incubated with 1 μg of recombinant CTCF protein (kindly provided by Paul Lieberman). We found that CTCF binding to fragment 2 resulted in a specific shift of this fragment to higher molecular complexes of different weights (Fig. 2B, lane 2), while incubation of CTCF protein with fragment 1 (no CBS present) did not reveal such shifting of complexes (Fig. 2B, lane 1). Supershifting to even higher molecular weights was observed after incubation of fragment 2 with recombinant CTCF and a specific CTCF antibody (Fig. 2B, lane 5). Thus, EMSA confirmed the binding of CTCF to the two CBS located between positions 107335 and 107403 of the HVS C488 genome. These sites are located upstream to a splice acceptor site for the orf73/LANA transcript and upstream of the initiation site for the HVS orf74 transcript located on the opposite strand.

Mutation of the first CBS results in an increase of orf73 promoter activity in luciferase reporter assays.

Having identified the two specific CBS, we next asked how these sites might influence the activity of either the orf73/LANA or the orf74 promoter. Therefore, we introduced these two promoters into a luciferase reporter plasmid either as wild-type sequences or with specific point mutations in the first or second CBS or both. Moreover, a deletion construct was generated lacking a 60-bp region comprising both CBS (Fig. 2C, upper panel). The luciferase gene was under the control of the respective promoter regions of either orf73/LANA or orf74. We analyzed the consequence of each mutation in HEK293T (nonpermissive for HVS) or in OMK cells (permissive for HVS). As can be seen, both wild-type promoters displayed a comparable amount of promoter activity. Regarding the promoter activity of orf74, only a minor influence of mutated or deleted CBS was observed: upon mutation of CBS the promoter activity seemed to decrease slightly (Fig. 2C, lower panels). Just in contrast was the finding for the orf73 promoter, where mutation or deletion of the first CBS increases the promoter activity of orf73/LANA, with little influence on the orf74 promoter (Fig. 2C, lower panel). Due to these reporter gene assays, we concluded that CTCF exerts different, directional modes in regard to the influence on the promoter region of orf73/orf74.

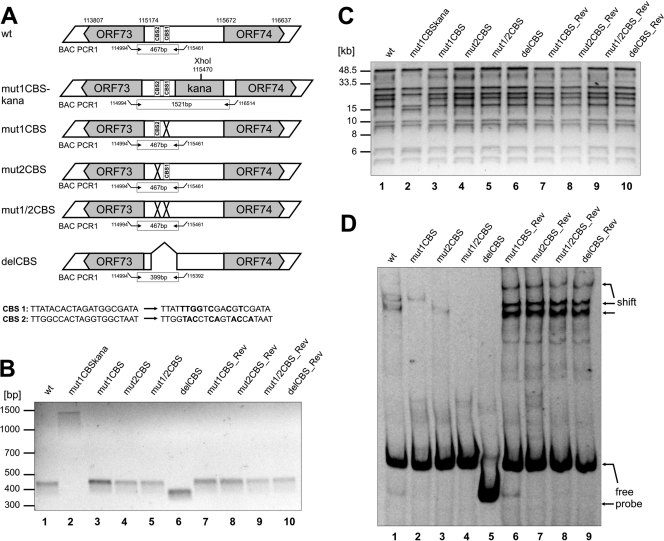

Generation of recombinant viruses.

In order to determine the functional significance of these CBS within the context of the viral genome, we generated different recombinant HVS CBS mutants and their respective revertants by site-directed mutagenesis of cloned HVS bacmid Bac43MOD (46) using the recombination-mediated genetic engineering (45). The wild-type bacmid sequence was verified by next generation sequencing (Illumina GA II, 2 × 108 bp paired reads) (data not shown), confirming intactness of the construct with respect to the published HVS genome sequence and, within the limitations of a short read sequencing method with regard to repetitive sequences, the absence of minor and major rearrangements in the L-DNA. The CBS at position one or two were specifically point mutated resulting in bacmid clones Bac43mut1CBS or Bac43mut2CBS, respectively. Furthermore, a double mutant (Bac43mut1/2CBS) was generated harboring both distinct point mutations of CBS. Finally, bacmid Bac43delCBS with a 60-bp deletion comprising both CBS was constructed (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Each mutant was then reverted to a wild-type sequence by the same technique. All mutants as well as their respective revertants were validated via PCR analysis, XhoI restriction enzyme digestion and PFGE, and direct sequencing of the recombined junctions (Fig. 3B and C). All of the experiments proved that the recombinant genomes contained the correct mutations or revertant wild-type sequences, with no other detectable rearrangements; they were therefore used for further analysis.

Fig 3.

Generation and characterization of recombinant HVS harboring point mutations or deletions within the CBS of the intergenic region of HVS orf73/orf74. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the structure of recombinant viruses that were generated by homologous recombination in E.coli. The upper part of panel A shows the genomic region of HVS strain C488 that contains CBS (numbers refer to nucleotide positions of HVS bacmid Bac43wt; BAC PCR1 refers to PCR amplification that was performed to confirm the integrity of recombinant viruses). The lower panels illustrate the recombinant viruses with indications of mutations/deletions of CBS (CBS 1, CTCF binding site 1; CBS 2, CTCF binding site 2; X, mutation; ⋀, deletion). For verification of the correct recombination sites within the HVS genome, all bacmid clones were analyzed by PCR and XhoI digest. (B) PCR analyses using oligonucleotides specific for the intergenic region orf73/orf74. The localization of primers used for amplification is shown in panel A (BAC PCR1). BAC PCR amplifies a fragment of 467 bp for the wild type, point mutants, and revertants or of 399 bp for the deletion mutant. Bacmids still harboring the aphAI gene display a PCR fragment of approximately 1.5 kb. The agarose gel shows the wild type (lane 1), mutant (lanes 3 to 6), and revertant (lanes 7 to 10) as well as a representative clone Bac43mut1CBS-kana (lane2) comprising the aphAI gene. (C) XhoI digest, pulse-field gel electrophoresis and subsequent ethidium bromide staining of 0.8% agarose gels of bacterial clones harboring the indicated bacmids. The aphAI cassette contains a single XhoI restriction site resulting in a different restriction pattern of bacmids containing the aphAI gene compared to the wild type, mutants, or revertants. The pulse-field gel electrophoresis shows wild-type bacmid (lane 1), mutants (lanes 3 to 6), and revertants (lanes 7 to 10) as well as one representative bacmid clone still harboring the aphAI cassette (Bac43mut1CBS-kana, lane 2). (D) EMSA with Cy5-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides generated by PCR from wt, mutant, or revertant bacmid clones displaying either no CBS mutations (wt, revertants) or specific CBS mutations (mut1CBS, mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, and delCBS). Oligonucleotides were incubated in the presence of recombinant CTCF protein before gel electrophoresis.

The sequences modified in the newly generated mutant and revertant bacmid clones were first checked for diminished or abrogated CTCF binding capacity by a fluorescent EMSA that was carried out similarly to Fig. 2B (Fig. 3D). Probes generated from all tested revertant bacmid clones displayed the same CTCF binding potential as wild-type Bac43MOD (Fig. 3D, lane 1 and lanes 6 to 9), where binding of CTCF results in a shifting of the DNA protein complex to higher molecular weights. However, the CBS double mutant Bac43mut1/2CBS as well as the deletion mutant Bac43delCBS were both abrogated in their ability to bind CTCF. Only an unbound, free probe was observed, and the incubation with recombinant CTCF protein did not result in higher molecular weight complexes (Fig. 3D, lanes 4 and 5). Regarding the single CBS point-mutated bacmid clones Bac43mut1CBS and Bac43mut2CBS, a diminished CTCF binding capacity was detected. Incubation of the respective probes still resulted in a shift of the DNA-protein complex. However, the complexes were different in size for the two mutants, arguing for distinct, specific CTCF binding arrangements at the two CBS (Fig. 3D, lanes 2 and 3).

Mutation or deletion of the CBS within the orf73/orf74 intergenic region results in no differences regarding the lytic infection cycle of these viruses.

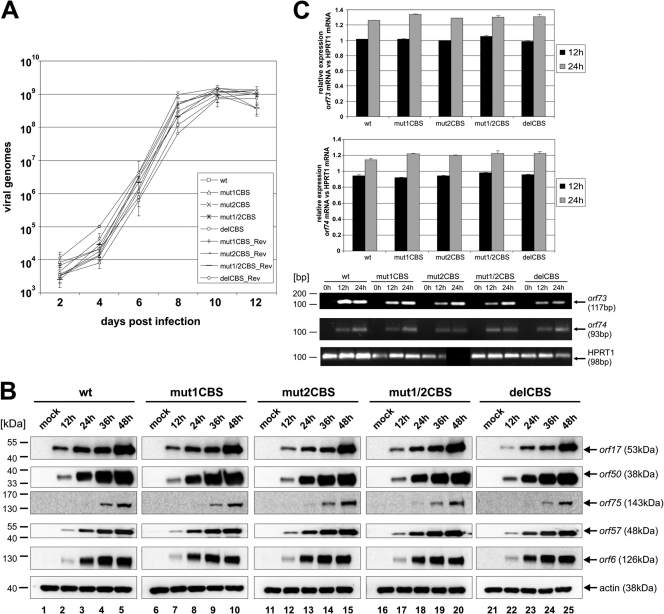

In all cases, it was possible to reconstitute virus from permissive OMK cells. In a first experiment, we aimed to analyze the lytic replication kinetics of the different viruses in OMK cells. All of the different viruses showed a comparable lytic infection cycle in regard to the establishment and progression of a cytopathic effect (CPE). Moreover, qPCR analysis showed that all viruses (wild type, mutant, and revertant) replicated in a comparable manner (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Lytic replication of recombinant Bac43-derived viruses. (A) Growth curve analyses. OMK cells were infected with equal amounts of viral genomes (MOI, 0.1) of wild-type, mutant, or revertant viruses. Lysates of infected cells and supernatants were generated at the indicated time points and subsequently used for quantification of viral genomes by real-time PCR of the major capsid protein (MCP; orf25). Evaluation was performed in triplicate. (B) Expression levels of different HVS proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific for proteins orf75, orf50, orf57, orf6, and orf17. Extracts were derived from identical number of permissive OMK cells, infected either with wt, mutant, or revertant viruses (MOI, 5) and harvested at indicated time points. (C) qRT-PCR orf73/74 mRNA. RNA was isolated from identical number of permissive OMK cells, which were infected with wt, mutant, or revertant viruses (MOI, 5) and harvested at indicated time points. RNA was assayed by qRT-PCR for RNA expression levels of orf73/orf74 in wt, mut1CBS, mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, delCBS, or one of the revertants. Cellular spliced HPRT1 mRNA was used as an internal standard.

Next we tested for differences in the protein expression levels between the different viruses. As shown in Fig. 4B, all of the generated viruses (wild type, mutant, and revertant viruses) displayed similar protein expression levels of the five different viral genes of orf6 (early), orf17 (early-late), orf50 (immediate early), orf57 (immediate early), and orf75 (late). Despite multiple attempts, we were not able to generate HVS orf73/LANA or orf74 specific antisera that allowed sensitive detection of the proteins. Therefore, we had to settle on analyzing the transcription of orf73/LANA and orf74 mRNAs by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 4C). The detected mRNA signals were normalized in relation to the spliced transcript of the cellular hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT1) gene. We found that orf73/LANA mRNA was expressed in mutant viruses at levels similar to that of the wild type and increased slightly over time (Fig. 4C, upper panel). Moreover, qRT-PCR revealed that orf74 mRNA levels for each mutant were also expressed to similar levels (Fig. 4C, middle panel). Melting point analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis was used to confirm that specific bands for each of the genes were analyzed (Fig. 4C, lower panel). All of these findings led us to the assumption that the CBS within the HVS orf73/orf74 promoter region have little or no influence on lytic replication.

Viruses comprising mutations or deletions of the two CBS show a significant decreased number of viral episomes in transformed human CBLs and have slightly decreased levels of orf73/LANA mRNA.

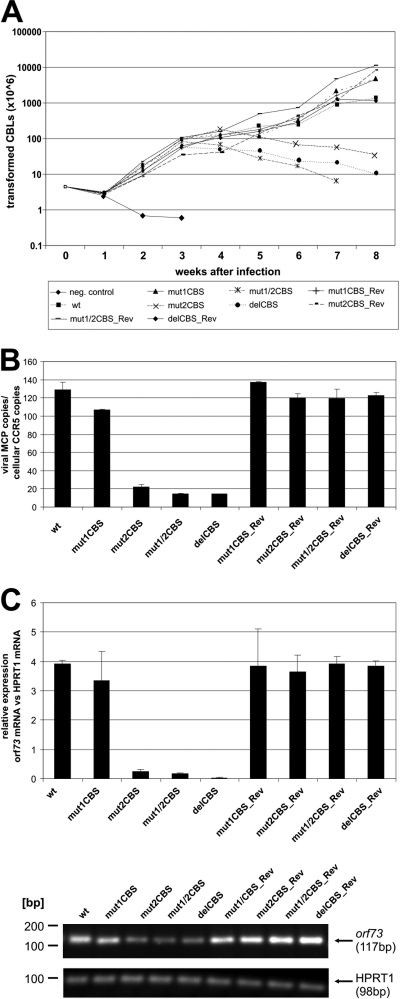

For an analysis of CBS mutants during the state of latency, CBLs of three different donors were infected with the respective mutant or revertant viruses and their proliferation was followed by determining cell numbers at indicated time points postinfection. As can be seen in the growth curve analysis shown in Fig. 5A, the mutant mut1CBS was not significantly inhibited for cell proliferation compared to wild type-containing cells or the revertant viruses. Interestingly, the T cells infected with mutants mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, and delCBS initially showed a proliferative capacity similar to the wild type; however, the growth of the respective T cell cultures started to cease approximately 4 to 5 weeks after infection and cells infected with the delCBS mutant began to die after approximately 6 weeks.

Fig 5.

Growth kinetics of T cells latently infected with recombinant Bac43-derived viruses. (A) Growth curve analyses. Human CBLs of three different donors were infected (equal amounts of viral genomes) of wild-type, mutant, or revertant viruses. The amount of proliferating cells was calculated by counting the amount of cells at different time points postinfection and multiplying it with the culture split ratio as conducted. One representative donor is shown (donor 2028). (B) Analysis of viral genome copy number in infected CBLs. Identical numbers of infected cells were harvested, lysed, and used for quantification of viral genomes by real-time PCR of MCP in comparison to cellular CCR5 copies. Evaluation was performed in triplicate. (C) qRT-PCR for orf73 mRNA. RNA was isolated from identical numbers of cells, which were infected with wild-type, mutant, or revertant viruses and harvested at 6 weeks postinfection. RNA was assayed by qRT-PCR for RNA expression levels of orf73 in comparison to cellular spliced HPRT1 mRNA. One representative donor is shown (donor 2028). Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to verify correct sizes of amplified PCR products of the qPCR analysis.

After we observed the decreased proliferation abilities, we hoped for further insight by assessing the episome copies of the different mutant genomes (mut1CBS, mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, and delCBS) within the latenly infected CBLs by comparing them to the revertants and HVS wild type (Fig. 5B). The average number of HVS episomes present within the cells was detected by quantitative qPCR of orf25/MCP in comparison to that of the cellular CCR5 gene. We were able to detect a significant decrease of episome copy number per cell present in CBLs infected by recombinant viruses mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, and delCBS (Fig. 5B). Under the hypothesis that loss of episomes in such mutants might be due to an alteration in orf73/LANA expression, we measured viral orf73/LANA mRNA by qRT-PCR in latently infected cells. This revealed a decrease in orf73/LANA mRNA expression per cell harboring the mut2CBS, mut1/2CBS, and delCBS recombinant genomes in relation to the cellular HPRT1 gene. However, as these cells contain less than 20% of HVS wild-type genome copies, the actual transcription level of orf73/LANA per viral genome copy is less significantly altered. The cDNA products derived by RT-PCR were sequenced and confirmed that no alterations occured in the orf73 mRNA splicing (data not shown). These observations suggest that a mutation and/or deletion of the second HVS CBS strongly interferes with a stable proliferation and HVS genome maintenance in infected CBLs.

DISCUSSION

Herpesviruses of all subgroups have been shown to establish latency in certain cells of a host organism. During the state of latency the viral genome persists as a circular, nonintegrating episome that is associated with cellular histones to form regular nucleosome-like structures (10, 26, 38). Viral gene expression is tightly regulated via epigenetic mechanisms and allows only the transcription of a few genes supporting the latent state. The structural organization and modification of viral chromatin is thought to be essential for herpesvirus persistence. We have shown that distinct histone modification patterns are established during HVS latency in transformed human T cells (1, 2).

Here we investigated the binding of the cellular insulator protein CTCF on the HVS genome, with additional fine-mapping and characterization of CBS conserved in primate rhadinoviruses. We identified two distinct CBS that specifically bind CTCF at the right end of the L-DNA (Fig. 1 and 2). The CBS are located within a homologous region to the major latency control region of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, a close relative of HVS, where such CBS have been previously reported (42). The two CBS lie within the intergenic region of HVS orf73/orf74 and more specifically locate to the intron region of the orf73/LANA promoter, which is spliced out in orf73/LANA mRNA transcripts (Fig. 1 and 2 A, B). The binding of CTCF in close proximity to the initiation site of major latency transcripts has also been observed for the HSV-1 latency-associated transcript (LAT) and EBV EBNA latency transcripts (3, 8, 9). Furthermore, our bioinformatic analysis also detected CBS in the corresponding promoter region of the LANA homolog in the related primate viruses Rhesus rhadinovirus and herpesvirus ateles, and also the T-lymphotropic Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 (13), but not in murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV68) (data not shown). The orf73/LANA gene product confers viral persistence by attaching the HVS episomes to metaphase chromosomes during mitosis (5, 19) and controls the reactivation of the viral lytic cascade as it efficiently represses transcription of the R transactivator protein (37). Therefore, the timely regulation of the orf73/LANA is essential for the establishment and maintenance of HVS latency as well as for reactivation.

The CCCTC-binding factor, short CTCF, is a protein that is able to structurally organize chromatin loci. CTCF is a multivalent, 11 zinc finger phosphoprotein that has been recognized to function in gene regulation as a chromatin boundary element or an enhancer-blocking insulator (15, 31, 49). The detection of CBS in the promoter region of orf73/LANA prompted us to search for an influence of CTCF on the structural organization, promoter activity and expression of orf73/LANA, in order to study how CTCF might contribute to the state of HVS latency in human T cells. We found that CTCF negatively regulated the orf73/LANA promoter in gene reporter assays, while there were only minor effects on the promoter activity of orf74 (Fig. 2C). The increase of the orf73/LANA promoter activity upon mutation of the first CTCF binding motif indicated that CTCF can potentially act as a repressor or enhancer blocker at this site (Fig. 2C). The role of CTCF as an enhancer blocking insulator protein has been shown at human loci like the H19/Igf2 imprinting control region, where binding of CTCF also correlated with conformational changes of the chromatin (25). At the human c-myc locus, the upstream enhancer activation of the proximal promoters can also be blocked by CTCF (31). Moreover, involvement of CTCF in the regulation of HSV-1 latency has been reported, where CTCF binds downstream of the LAT promoter, thereby preventing the expression of ICP0, the HSV-1 lytic (re-)activator gene (3, 8).

We also sought to analyze the effect of such CBS in the contexts of viral lytic replication and latency. For this purpose, we generated different recombinant viruses with CBS mutations, as well as their respective revertant viruses to control for undetected second site mutations (Fig. 3). Interestingly, CTCF seems to have different binding arrangements at the two distinct CBS and it is tempting to speculate that complexes of CTCF with different partners and configurations can exert different functions (Fig. 3D). As we assumed that CTCF mainly functions as an epigenetic modifier of chromatin structures which are present particularly during herpesviral latency, we were not surprised by the finding that mutant viruses were highly similar in regard to their lytic replication (Fig. 4). This is in line with the hypothesis that the CTCF protein has little or no influence during the lytic replication cascade of HVS.

Remarkably, CBS turned out to be of great importance in regard to the maintenance of HVS episomes in latently infected human T cells. Human cord blood lymphocytes that were infected with recombinant HVS viruses harboring mutations or deletions in the second CBS or both showed reduced proliferation capacities (Fig. 5A). As the viral genome copy number per cell was also significantly decreased in cells infected with these mutant viruses, we concluded a direct involvement of CTCF in episome maintenance. Due to a loss of HVS genomes in T cells infected with such mutant viruses, the transformed state, which is a consequence of the viral oncoproteins StpC and Tip, cannot be maintained (Fig. 5B). This finding strongly argues for a contribution of the interaction between CTCF and the second CBS to the persistence of viral episomes. Such an attribution is conceivable, since it has been reported that CTCF can form loops in cis and can bridge sequences located on different chromosomes in trans (55). Recent publications have suggested that loop formation promoted by CTCF is also involved the establishment of the different latency types of EBV. It was shown that CTCF generates distinct chromatin architectures of EBV episomes, which results in variable promoter selection typical for the different gene expression patterns of EBV latency types (43). Moreover, our data are in agreement with publications for KSHV, where it has been shown that CBS mutations within the KSHV genome resulted in a decrease of transfected viral episomes over time at a comparable magnitude to HVS (22, 42). This underlines the importance of CTCF for the maintenance of stable rhadinovirus genome copy number in latently infected cells. However, the results for KSHV were obtained after transient transfection of KSHV bacmids into 293T cells, while our study investigated HVS transformed, latently infected T cells. Furthermore, the studies for KSHV did not analyze the CBS separate from each other; we were able to provide first indications that the different CBS may account for different functions and that especially the second CBS is of importance with regard to stable episomal maintenance of HVS genomes.

Cohesins have recently been found to be involved in CTCF function with regard to the establishment of intrachromosomal loop formation (17). These molecules primarily function in maintaining sister-chromatid cohesion and are necessary not only for correct chromosome segregation but also for facilitating the repair of damaged DNA by homologous recombination (28, 34). It was discovered that cohesins share a highly similar consensus binding sequence with CTCF and colocalize with CTCF at many sites (32, 42, 50). We suspect that cohesins might contribute to CTCF function by stabilizing the attachment of the viral episomes to metaphase chromosomes during cell division. This hypothesis is supported by an investigation in KSHV, where it has been shown that cohesion subunits colocalize to the CBS found at the major latency control region and that these molecules are involved in complex gene regulation and chromatin organization (42). The loss of viral episomes might be, in part, the result of a reduction of orf73/LANA mRNA transcript detected in these T cells (Fig. 5C). However, taking into account that there is a corresponding reduction of viral genome copy number of mutant viruses in such human T cells, one could also argue that, per genome, comparable levels of transcription of the orf73/LANA gene occur at the remaining genomes; the loss of viral genomes in mutant virus-infected cells thus might not be a consequence of the deregulation of orf73/LANA. A simple siRNA experiment to knock down LANA cannot address this, as the polycistronic nature of the LANA transcript would also influence the viral cyclin and FLIP homologs; further studies using recombinant viruses might be required to shed light on the role of LANA versus CTCF.

Taking our data together, it is possible that CTCF, when bound at the orf73/LANA promoter region, is able to exert two different functions during HVS latency. This assumption is assisted by the finding that CTCF establishes two distinct binding arrangements at this gene region (Fig. 3D). First, CTCF can act as a regulator of transcription of the orf73/LANA gene expression. By influencing this promoter region CTCF might be involved in the regulation of the viral lytic cascade initiated by the R transactivator protein of orf50, which is regulated by the orf73/LANA gene product.

More importantly, we speculate that CTCF might contribute to the function of the orf73/LANA gene product in viral genome segregation. CTCF (and cohesins) may be involved in tightly tethering the viral episomes to metaphase chromosomes, thereby guaranteeing proper separation of HVS genomes to daughter cells. In the future, studies of viral chromatin conformation and virus-host chromatin interaction using recombinant viruses will probably shed more light on the role of CTCF in rhadinovirus biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Lieberman (Philadelphia, PA) for recombinant CTCF protein. We also thank Doris Lengenfelder, Brigitte Scholz, and Benjamin Vogel for helpful advice and Bernhard Fleckenstein for continuous support.

This study was supported by BIGSS (BioMedTec International Graduated School of Science) of the Elitenetzwerk Bayern, DFG SFB796, the Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung, and the Novartis-Stiftung für therapeutische Forschung.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 November 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Alberter B, Ensser A. 2007. Histone modification pattern of the T-cellular herpesvirus saimiri genome in latency. J. Virol. 81:2524–2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alberter B, Vogel B, Lengenfelder D, Full F, Ensser A. 2011. Genome-wide histone acetylation profiling of herpesvirus saimiri in human T cells upon induction with a histone deacetylase inhibitor. J. Virol. 85:5456–5464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amelio AL, McAnany PK, Bloom DC. 2006. A chromatin insulator-like element in the herpes simplex virus type 1 latency-associated transcript region binds CCCTC-binding factor and displays enhancer-blocking and silencing activities. J. Virol. 80:2358–2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Biesinger B, et al. 1992. Stable growth transformation of human T lymphocytes by herpesvirus saimiri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:3116–3119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calderwood M, White RE, Griffiths RA, Whitehouse A. 2005. Open reading frame 73 is required for herpesvirus saimiri A11-S4 episomal persistence. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2703–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calderwood MA, Hall KT, Matthews DA, Whitehouse A. 2004. The herpesvirus saimiri ORF73 gene product interacts with host-cell mitotic chromosomes and self-associates via its C terminus. J. Gen. Virol. 85:147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chau CM, Zhang XY, McMahon SB, Lieberman PM. 2006. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency type by the chromatin boundary factor CTCF. J. Virol. 80:5723–5732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Q, et al. 2007. CTCF-dependent chromatin boundary element between the latency-associated transcript and ICP0 promoters in the herpes simplex virus type 1 genome. J. Virol. 81:5192–5201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Day L, et al. 2007. Chromatin profiling of Epstein-Barr virus latency control region. J. Virol. 81:6389–6401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deshmane SL, Fraser NW. 1989. During latency, herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is associated with nucleosomes in a chromatin structure. J. Virol. 63:943–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duboise SM, Guo J, Czajak S, Desrosiers RC, Jung JU. 1998. STP and Tip are essential for herpesvirus saimiri oncogenicity. J. Virol. 72:1308–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ensser A, Pfinder A, Müller-Fleckenstein I, Fleckenstein B. 1999. The URNA genes of herpesvirus saimiri (strain C488) are dispensable for transformation of human T cells in vitro. J. Virol. 73:10551–10555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ensser A, Pflanz R, Fleckenstein B. 1997. Primary structure of the alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 genome. J. Virol. 71:6517–6525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ensser A, Thurau M, Wittmann S, Fickenscher H. 2003. The genome of herpesvirus saimiri C488 which is capable of transforming human T cells. Virology 314:471–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Felsenfeld G, et al. 2004. Chromatin boundaries and chromatin domains. Cold Spring Harbor. Symp. Quant. Biol. 69:245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleckenstein B, Desrosiers RC. 1982. Herpesvirus saimiri and herpesvirus ateles, p 253–332. In Roizman B. (ed), The herpesviruses. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gause M, Schaaf CA, Dorsett D. 2008. Cohesin and CTCF: cooperating to control chromosome conformation? Bioessays 30:715–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gombert WM, et al. 2003. The c-myc insulator element and matrix attachment regions define the c-myc chromosomal domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:9338–9348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Griffiths R, Whitehouse A. 2007. Herpesvirus saimiri episomal persistence is maintained via interaction between open reading frame 73 and the cellular chromosome-associated protein MeCP2. J. Virol. 81:4021–4032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heck E, et al. 2006. Growth transformation of human T cells by herpesvirus saimiri requires multiple Tip-Lck interaction motifs. J. Virol. 80:9934–9942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang H, Lieberman PM. 2009. Cell cycle control of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency transcription by CTCF-cohesin interactions. J. Virol. 83:6199–6210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kang H, Wiedmer A, Yuan Y, Robertson E, Lieberman PM. 2011. Coordination of KSHV latent and lytic gene control by CTCF-cohesin mediated chromosome conformation. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim TH, et al. 2007. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell 128:1231–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komatsu T, Barbera AJ, Ballestas ME, Kaye KM. 2001. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen. Viral Immunol. 14:311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurukuti S, et al. 2006. CTCF binding at the H19 imprinting control region mediates maternally inherited higher-order chromatin conformation to restrict enhancer access to Igf2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:10684–10689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lieberman PM. 2006. Chromatin regulation of virus infection. Trends Microbiol. 14:132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ling JQ, et al. 2006. CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science 312:269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Losada A. 2008. The regulation of sister chromatid cohesion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1786:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Medveczky MM, et al. 1989. Herpesvirus saimiri strains from three DNA subgroups have different oncogenic potentials in New Zealand white rabbits. J. Virol. 63:3601–3611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mukhopadhyay R, et al. 2004. The binding sites for the chromatin insulator protein CTCF map to DNA methylation-free domains genome-wide. Genome Res. 14:1594–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V. 2001. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet. 17:520–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parelho V, et al. 2008. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell 132:422–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paulus C, Nitzsche A, Nevels M. 2010. Chromatinisation of herpesvirus genomes. Rev. Med. Virol. 20:34–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peters JM, Tedeschi A, Schmitz J. 2008. The cohesin complex and its roles in chromosome biology. Genes Dev. 22:3089–3114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rawlins DR, Milman G, Hayward SD, Hayward GS. 1985. Sequence-specific DNA binding of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA-1) to clustered sites in the plasmid maintenance region. Cell 42:859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roizman B. 1996. Herpesviridae, p 2221–2636. In Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Virology. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schäfer A, et al. 2003. The latency-associated nuclear antigen homolog of herpesvirus saimiri inhibits lytic virus replication. J. Virol. 77:5911–5925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shaw JE, Levinger LF, Carter CW., Jr 1979. Nucleosomal structure of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in transformed cell lines. J. Virol. 29:657–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simmer B, et al. 1991. Persistence of selectable herpesvirus saimiri in various human haematopoietic and epithelial cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 72:1953–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spilianakis CG, Flavell RA. 2006. Molecular biology. Managing associations between different chromosomes. Science 312:207–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Splinter E, et al. 2006. CTCF mediates long-range chromatin looping and local histone modification in the beta-globin locus. Genes Dev. 20:2349–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stedman W, et al. 2008. Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. EMBO J. 27:654–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tempera I, Klichinsky M, Lieberman PM. 2011. EBV latency types adopt alternative chromatin conformations. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tempera I, Lieberman PM. 2010. Chromatin organization of gammaherpesvirus latent genomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799:236–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tischer BK, von Einem J, Kaufer B, Osterrieder N. 2006. Two-step red-mediated recombination for versatile high-efficiency markerless DNA manipulation in Escherichia coli. Biotechniques 40:191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toptan T, Ensser A, Fickenscher H. 2010. Rhadinovirus vector-derived human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression in primary T cells. Gene Ther. 17:653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Toth Z, et al. 2010. Epigenetic analysis of KSHV latent and lytic genomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verma SC, Robertson ES. 2003. ORF73 of herpesvirus saimiri strain C488 tethers the viral genome to metaphase chromosomes and binds to cis-acting DNA sequences in the terminal repeats. J. Virol. 77:12494–12506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wallace JA, Felsenfeld G. 2007. We gather together: insulators and genome organization. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17:400–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wendt KS, et al. 2008. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature 451:796–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Williams A, Flavell RA. 2008. The role of CTCF in regulating nuclear organization. J. Exp. Med. 205:747–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yusufzai TM, Felsenfeld G. 2004. The 5′-HS4 chicken beta-globin insulator is a CTCF-dependent nuclear matrix-associated element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:8620–8624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G. 2004. CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol. Cell 13:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhao H, Dean A. 2004. An insulator blocks spreading of histone acetylation and interferes with RNA polymerase II transfer between an enhancer and gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:4903–4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zlatanova J, Caiafa P. 2009. CTCF and its protein partners: divide and rule? J. Cell Sci. 122:1275–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]