Abstract

Objective

Clinical neurologic signs considered predictive of adverse outcome after pediatric cardiac arrest (CA) may have a different prognostic value in the setting of therapeutic hypothermia (TH). We aimed to determine the prognostic value of motor and pupillary responses in children treated with TH after CA.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Pediatric ICU in tertiary care hospital.

Patients

Children treated with TH after CA.

Measurements and Main Results

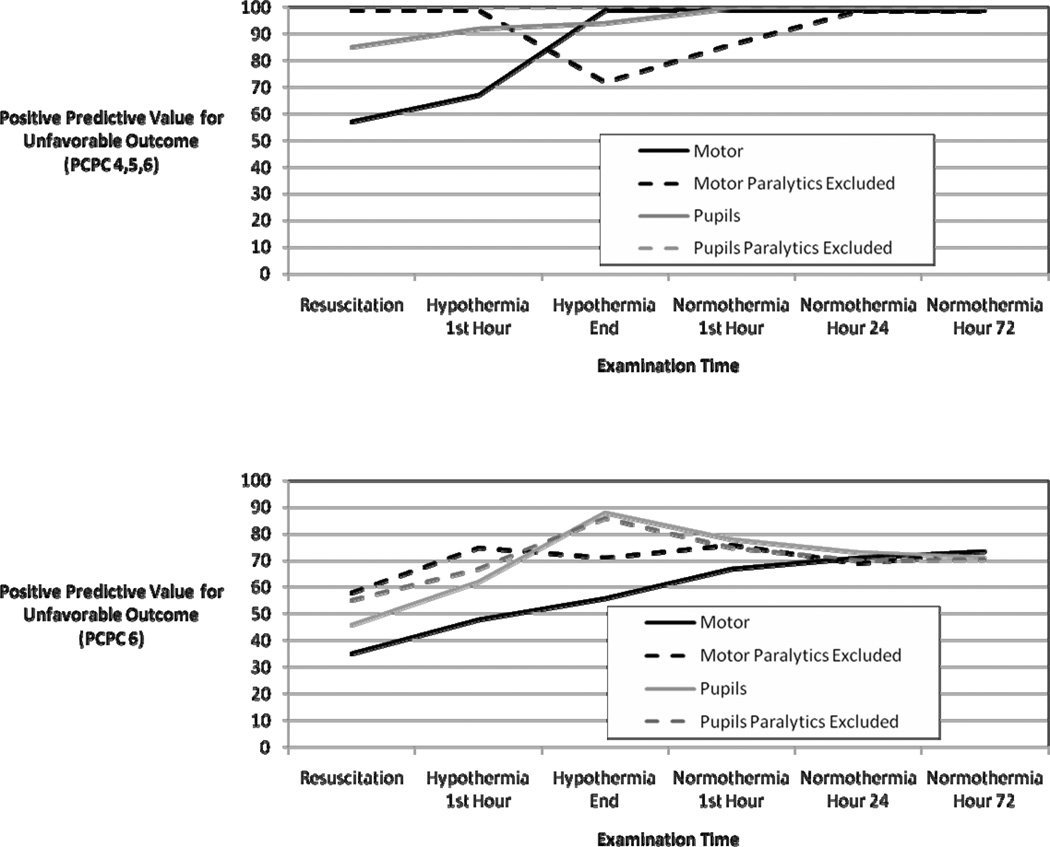

Thirty-five children treated with TH after CA were prospectively enrolled. Examinations were performed by emergency medicine physicians and intensive care unit bedside nurses. Examinations were performed after resuscitation, 1 hour after achievement of hypothermia, during the last hour of hypothermia, 1 hour after achievement of normothermia, after 24 hours of normothermia, and after 72 hours of normothermia. The primary outcome was unfavorable outcome at ICU discharge, defined as a Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score of 4–6 at hospital discharge. The secondary outcome was death (PCPC = 6). The associations between exam responses and unfavorable outcomes (as both PCPC 4,5,6 and PCPC 6) are presented as positive predictive values (PPV), for both all subjects and subjects not receiving paralytics. Statistical significance for these comparisons was determined using Fisher’s exact test. At all examination times and examination categories PPV is higher for the unfavorable outcome PCPC 4,5,6 than PCPC 6. By normothermia hour 24, absent motor and pupil responses were highly predictive of unfavorable outcome (PCPC 4,5,6) (PPV 100% and p<0.03 for all categories), while at earlier times the predictive value was lower.

Conclusions

Absent motor and pupil responses are more predictive of unfavorable outcome when defined more broadly than when defined as only death. Absent motor and pupil responses during hypothermia and soon after return of spontaneous circulation were not predictive of unfavorable outcome while absent motor and pupil responses once normothermic were predictive of unfavorable short-term outcome. Further study is needed using more robust short-term and long-term outcome measures.

Keywords: Therapeutic Hypothermia, Neurological Examination, Pediatric, Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy, Cardiac Arrest, Prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Early prognostication in children after cardiac arrest (CA) is important in counseling families and making management decisions (1). Multiple clinical, laboratory, imaging, and electrographic features may be useful in outcome prediction, but none have perfect predictive value (2). A recent American Academy of Neurology practice parameter focused on outcome prediction in adults after CA concluded that absent pupillary, corneal, and motor responses three days after cardiac arrest were predictive of poor neurologic outcome (3). However, this guideline did not address the pediatric age group and was based on studies that preceded the use of therapeutic hypothermia (TH). Several studies have described the predictive value of physical examination findings in children after CA, but were also conducted without TH as a component of clinical management (4–7). It is unknown whether these signs retain their predictive value when a patient is treated with TH (1). A recent case series of adults who underwent TH after CA reported that 2 of 14 patients with absent motor responses on day 3 regained consciousness (8), suggesting some findings may have altered predictive value when TH is utilized. Prognostic information early after CA may be useful, but only if early findings are accurate. It is unknown whether TH utilization impacts the timing at which individual examination signs are predictive of outcome in children.

The objective of this study was to prospectively evaluate the predictive value of neurologic signs at specific times in children treated with therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. We aimed to determine whether the presence or absence of these neurologic signs at specific time-points were predictive of unfavorable short term outcomes. We hypothesized that hypothermia would affect neurologic signs, and therefore findings soon after resuscitation or during hypothermia would not be as predictive of ICU discharge outcome as signs later (e.g, after return to normothermia).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

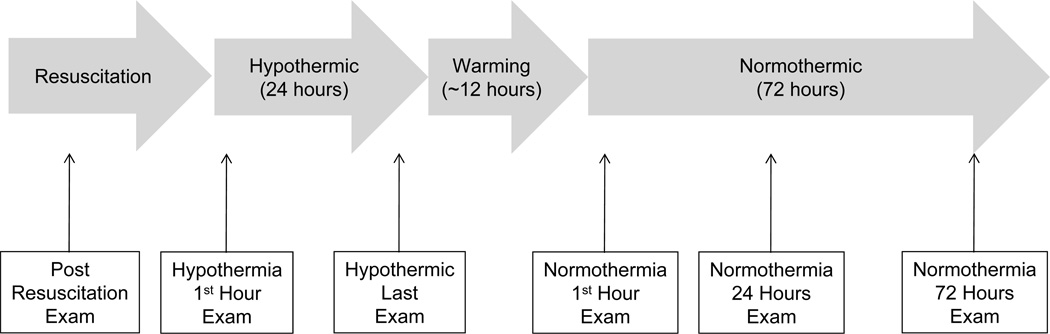

Children who experienced an in- or out-of-hospital CA and achieved return of spontaneous circulation were treated using this institution’s pediatric intensive care unit’s standard clinical TH protocol. Hypothermia was induced by a cooling blanket to 32–34° Celsius and maintained for 24 hours. Patients were then slowly re-warmed over 12–24 hours to a temperature of > 36.5° Celsius. Informed consent was obtained during the therapeutic hypothermia course. Patients who died prior to consent were not included. Consecutive children younger than 18 years of age were enrolled. Neonates were not included. This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Review Board.

Data collected included demographic information, cardiac arrest details, clinical neurological examination findings (pupillary light responses and motor responses to noxious stimulation) at specific times, medications (including paralytics and sedating medications) and short-term outcome.

Patients were managed by ICU and neurology services per routine clinical care. Monitoring with arterial catheters and central venous lines was standard of care. Standard respiratory and hemodynamic targets were normoventilation, normoxia and normotension. Standard sedation infusions were fentanyl and midazolam and were administered to patients to maintain comfort. Paralysis was not routinely administered, but was utilized to minimize shivering and when clinically indicated. EEG monitoring was routine for patients to evaluate for non-convulsive seizures (9). Prophylactic anticonvulsants were not administered. If clinical seizures or non-convulsive seizures were identified patients were treated in conjunction with neurology consult service.

Examinations were performed by emergency medicine physicians at resuscitation and by PICU bedside nurses for the other timepoints according to standard clinical and institutional practice. Pupil examination was performed by shining a bright light in each pupil and evaluating whether pupil constriction occurred. Pupil responses were scored as present if detected in either eye. Motor exam was performed by observing any movement after tactile stimulation, including sternal rub or pinch if less intense stimuli failed to evoke a response. Motor response was scored as present if detected in any extremity with any degree of stimulation. Motor and pupil examinations were performed at 6 specific times (Figure 1). Examinations were performed after resuscitation, 1 hour after achievement of hypothermia (temperature < 34° C), during the last hour of hypothermia, 1 hour after achievement of normothermia (temperature > 36.5°C), after 24 hours of normothermia, and after 72 hours of normothermia. If paralytics were administered within 2 hours of the examination time then the examination was considered potentially confounded. Data are presented for all subjects and the subset of subjects who were not receiving paralytics for both motor and pupil responses.

Figure 1.

Short-term outcome was determined on discharge from the intensive care unit based on the pediatric cerebral performance category score (PCPC) (10). The PCPC is a validated six point scale categorizing degrees of functional impairment. PCPC scores and categories are 1 = normal, 2 = mild disability, 3 = moderate disability, 4 = severe disability, 5 = coma and vegetative state, and 6 = death. The primary outcome was unfavorable short-term outcome defined as PCPC score of 4–6 (severe disability, vegetative state, or death). The secondary outcome considered death alone (PCPC score 6).

Patient characteristics are reported as means and standard deviations for normally distributed variables and median and ranges for non-normally distributed variables. To evaluate whether absent examination responses predicted unfavorable outcome at each timepoint, positive predictive values (PPV) and areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were calculated. The strength of the association between exam findings at each of the three timepoints and the primary or secondary outcomes is presented as odds ratios. Univariate comparisons for outcome were performed using Fisher exact tests for the dichotomous predictor variables, motor and pupil exams. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA release 10.1 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient and Cardiac Arrest Characteristics

Between June 2007 and July 2009, 35 consecutive children underwent TH after CA, including 20 males and 15 females, with a median age 1.02 years (range 0.18 – 16.6 years). No families declined enrollment. Prior to CA 21 were normal, 9 had neuro-developmental problems, and 5 had pre-existing medical problems but were considered neuro-developmentally normal. Six (17%) suffered an in-hospital cardiac arrest and 29 (83%) suffered an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Four (11%) had initial ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia. Duration of CPR was unknown for 12 subjects. For the other 23, the median duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation was 15 minutes (interquartile range 6, 21). Arrest etiologies were asphyxia/respiratory in 16, drowning in 8, primary cardiac in 5, and other in 4 (2 near-SIDS, 1 anaphylaxis, 1 unknown).

For 24 subjects with detailed return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) timing data available, the mean duration between ROSC and hypothermia (temperature < 34° Celsius) was 7.3 ± 0.2 hours. The mean duration between ROSC and examinations was 2.1 ± 2.9 hours for resuscitation exam, 6.5 ± 5.3 hours for hypothermia first hour exam, 30.5 ± 12.7 hours for the hypothermia end exam, 45.4 ± 20.9 hours for the normothermia first hour exam, 66.7 ± 26.2 hours for the normothermia 24 hours exam, and 110.4 ± 40.7 hours for the normothermia 72 hours exam.

Twenty (57%) survived to ICU discharge. The median length of ICU stay was 8 days (range 2–154 days). Of the survivors, 4 had a PCPC score of 5, 5 had a PCPC score of 4, 3 had a PCPC score of 3, 2 had a PCPC score of 2, and 7 had a PCPC score of 1. Fifteen subjects died, of whom 11 had withdrawal of technologic support and 4 were brain dead.

Of the 9 with prior neuro-developmental problems, 5 had chronic static encephalopathy related to prematurity and hypoxic ischemic brain injury, 2 had pervasive developmental disorders, and 2 had Trisomy 21. The median PCPC score prior to cardiac arrest was 3.3 (range 3–4) while the median PCPC score post-arrest was 4.7 (range 4–6). All 9 patients with prior neuro-developmental problems exhibited a decrease in PCPC score following the arrest.

Predictive Value of Exam Findings for Short Term Outcome

The predictive values of motor and pupil responses, when performed during the six timepoints for the primary (PCPC 4,5,6) and secondary (PCPC 6) outcomes, are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. For each timepoint and outcome, the PPV is shown for all subjects (including those with examinations potentially confounded by paralytics) and for only subjects without any paralytic administration within 2 hours of the examination time. Examination abnormalities were always more predictive of unfavorable outcome when outcome was defined more broadly (PCPC 4,5,6) than when defined as death (PCPC 6). Early examinations were not highly predictive of unfavorable outcome. However, the absence of motor and pupil responses following return to normothermia predicted unfavorable outcome (PCPC 4,5,6). Paralytic administration lowered the predictive value of motor responses more than pupil responses, and when subjects who received paralytics were excluded motor examination had a high predictive value early in the course including during hypothermia.

Table 1.

Examination signs and outcome.

| Exam Time | Exam Sign (N) | Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavorable Outcome = PCPC 4,5,6 | Unfavorable Outcome = PCPC 6 | ||||||

| PPV (95% CI) | Area Under ROC Curve (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio (P Value) | PPV (95% CI) | Area Under ROC Curve (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio (P Value) | ||

| Resuscitation | Absent Motor (all) (29) Absent Motor (limited) (18) Absent Pupil (all) (26) Absent Pupil (limited) (17) |

56.52% (38.5%–74.6%) 100% 84.62% (70.8%–98.5%) 100% |

0.41 (0.3–0.5) 0.85 (0 – 1) 0.68 (0.5–0.9) 0.84 (0 – 1) |

0.26 (0.34) *(0.33) 4.71 (0.20) *(0.35) |

34.78% (17.5%–52.1%) 58.33% (35.6%–81.1%) 46.15% (27%–65.3%) 54.55% (30.9%–78.2%) |

0.45 (0.3–0.6) 0.54 (0.3–0.8) 0.63 (0.4–0.8) 0.60 (0.4–0.8) |

0.53 (0.65) 1.4 (1) 2.86 (0.41) 2.4 (0.62) |

| Hypothermia 1st Hour |

Absent Motor (all) (35) Absent Motor (limited) (18) Absent Pupil (all) (35) Absent Pupil (limited) (18) |

66.67% (51%–82.2%) 100% 92.31% (83.5%–101.1%) 100% |

0.47 (0.3–0.6) 0.85 (0 – 1) 0.70 (0.6–0.8) 0.76 (0 – 1) |

0.07 (1) *(0.33) 10 (0.03) *(1) |

48.15% (31.6%–64.7%) 75% (55%–95%) 61.54% (45.4%–77.7%) 66.67% (44.89%–88.44%) |

0.58 (0.5–0.7) 0.69 (0.5–0.9) 0.64 (0.5–0.8) 0.56 (0.3–0.8) |

2.76 (0,42) 6 (0.14) 3.43 (0.16) 1.6 (1) |

| Hypothermia End |

Absent Motor (all) (35) Absent Motor (limited) (27) Absent Pupil (all) (35) Absent Pupil (limited) (27) |

72% (57.1%–86.9%) 94.12% (85.2%–103%) 100% 100% |

0.56 (0.4–0.7) 0.76 (0.5–1) 0.67 (0.6–0.7) 0.66 (0.56–0.8) |

1.71 (0.69) 10.67 (0.05) *(0.04) *(0.28) |

56% (39.55%–72.45%) 70.59% (53.4%–87.8%) 87.50% (76.5%–98.5%) 85.71% (72.5%–99%) |

0.69 (0.6–0.8) 0.78 (0.6–0.9) 0.71 (0.6–0.9) 0.70 (0.5–0.9) |

11.45 (0.02) 21.6 (0.004) 16.63 (0.01) 11.14 (0.03) |

| Normothermia 1st Hour |

Absent Motor (all) (35) Absent Motor (limited) (29) Absent Pupil (all) (35) Absent Pupil (limited) (29) |

85.71% (74.1%–97.3%) 100% 100% 100% |

0.74 (0.6–0.9) 0.89 (0.8–1) 0.69 (0.6–0.8) 0.68 (0.6–0.8) |

8 (0.01) * (0.001) * (0.03) * (0.14) |

66.67% (51%–82.3%) 76.47% (61%–92%) 77.78% (64%–91.5%) 75%(59.2%–90.8%) |

0.79 (0.7–0.9) 0.83 (0.7–1) 0.68 (0.54–0.83) 0.65 (0.5–0.8) |

26 (0.001) 35.75 (0.001) 7.88 (0.02) 4.88 (0.11) |

| Normothermia Hour 24 |

Absent Motor (all) (32) Absent Motor (limited) (30) Absent Pupil (all) (32) Absent Pupil (limited) (30) |

100% 100% 100% 100% |

0.89 (0.8–1) 0.88 (0.8–1) 0.75 (0.6–0.9) 0.74 (0.6–0.8) |

*(<0.0001) *(0.0001) *(0.01) *(0.01) |

70.59% (54.8%–86.4%) 68.75% (52.2%–85.3%) 72.73% (57.3%–88.2%) 70% (53.6%–86.4%) |

0.83 (0.7–1) 0.82 (0.7–1) 0.73 (0.6–0.9) 0.71 (0.5–0.9) |

33.6 (0.0003) 28.6 (0.001) 8.53 (0.02) 7 (0.05) |

| Normothermia Hour 72 |

Absent Motor (all) (29) Absent Motor (limited) (29) Absent Pupil (all) (29) Absent Pupil (limited) (29) |

100% 100% 100% 100% |

0.81 (0.7–0.9) 0.81 (0.7–1) 0.70 (0.6–0.8) 0.69 (0.6–0.8) |

*(0.001) *(0.001) *(0.03) *(0.03) |

72.73% (56.5%–88.9%) 72.73% (56.5%–88.9%) 71.43% (55%–87.9%) 71.43% (55%–87.9%) |

0.87 (0.7–1) 0.87 (0.7–1) 0.73 (0.5–0.9) 0.73% (0.5–0.9) |

45.33 (0.0003) 45.33 (0.0003) 11.25 (0.0164) 11.25 (0.016) |

=Inestimable since no subjects with absent response had good outcome.

PPV = positive predictive value

ROC = receiver operating characteristic

CI = confidence interval

PCPC = pediatric cerebral performance category score

all = includes all subjects limited = subjects receiving paralytics within 2 hours excluded

Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

In children treated with TH after CA, motor and pupil responses immediately after resuscitation and during hypothermia were not highly predictive of short-term outcome. This suggests that prognostication based on examination may need to be delayed until longer after ROSC and after return to normothermia when the absence of pupillary and motor reflexes become predictive of unfavorable short-term neurologic outcome. Examination signs were less predictive of death alone than more broadly defined unfavorable short-term outcomes.

These current data are consistent with studies of physical examination in adults who have experienced CA. A meta-analysis of studies assessing outcome in 1914 adult comatose survivors of CA not treated with TH demonstrated that the absence of corneal reflexes, pupillary light reflexes, and absent motor response at 24 hours and absent motor response at 72 hours strongly predicted death or poor neurological outcome (11). Unfortunately, no signs were identified that allowed accurate prognostication before 24 hours, and no signs strongly predicted good neurological outcome. The American Academy of Neurology practice parameter focused on adults describes that certain clinical findings accurately predict poor outcome, including absence of pupillary responses, corneal responses, and absent or extensor motor responses three days after cardiac arrest (3). Similarly, predictive examinations in our series occurred between 2–3 days after resuscitation (45 hours for normothermia first hour exam and 67 hours for the normothermia 24 hours exam) suggesting that the timing of predictive examinations relative to resuscitation may be more important than the temperature management occurring in the interval between resuscitation and examination at 2–3 days.

Unfortunately, no similarly extensive studies have been conducted in children. Mandel et al. reported that in 57 children with HIE, the absence of spontaneous ventilation and absence of pupillary reflexes 24 hours after the insult had a PPV of unfavorable outcome (death, vegetative state, or severe disability by pediatric cerebral and overall performance category scale at 3 years) of 100% but neurologic signs at admission were not predictive (4). Bratton et al. described 44 children after near-drowning and reported that all children with purposeful movements and normal brainstem function at 24 hours after resuscitation had a good outcome, while all without purposeful movement and with abnormal brainstem signs had severe neurological impairments or died (5). Carter and Butt reported that in 36 children with HIE the sensitivity and specificity of abnormal motor and pupillary responses for unfavorable outcomes (death, vegetative, or severe disability and dependence by Glascow Outcome Scale at 5 years) were 93%/50% and 47%/100% respectively during the initial 9 days of the admission. Seven patients with abnormal motor responses had better than expected outcome. Each of these patients had preserved somatosensory evoked potentials on at least one side (6). In a study of 109 children with acute severe brain injury from multiple etiologies (including HIE and traumatic brain injury), Beca et al. reported that the absence of motor responses to pain on day three after injury had PPV for unfavorable outcome (death, vegetative, or severely disability and dependence by Glascow Outcome Scale at greater than 6 months) of 100%. However, the 95% confidence interval was 84–100% and 23% of patients could not be evaluated due to use of sedative or paralytic medications (7). Together, these studies suggest that when not confounded by medications, the neurological examination is quite predictive for children with hypoxic ischemic brain injury when performed more than 24 hours after the inciting event in the absence of TH. After 24 hours, the absence of brainstem signs and motor responses to painful stimuli portend an unfavorable prognosis.

TH has been shown to improve outcome after CA in adults (12, 13) and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in neonates (14–16), and is sometimes empirically employed in children after CA (17–19). If hypothermia is neuroprotective then predictive models based on data from patients treated without TH may no longer be reliable. Three adult studies have addressed this issue. Rossetti et al. reported 111 comatose adults after cardiac arrest treated with TH and there were substantial false positive rates. The absence of motor responses did not predict unfavorable outcome in 24% of patients and myoclonus did not predict unfavorable outcome in 7% (20). Al Thenayan et al. described 37 adults who underwent TH after CA. Two of 14 (14%) without motor responses on day 3 regained consciousness (8). In a rebuttal report, Freeman et al. described 25 patients who received TH after CA. Five patients without pupillary response and 8 patients without motor response at 72 hours never regained consciousness, demonstrating a 0% false positive rate (21). This suggests caution is required when providing a prognosis based on motor responses since some patients treated with TH may have better outcome than expected.

Paralytic medications may mask the physical exam and may have extended half-lives in children with hypoxic injury to their liver or kidneys. Thus, clinicians must constantly bear in mind the uncertainty of their serum levels when formulating a prognosis based only on the physical examination. The current study analyzed the predictive value among both the full cohort of children and the subgroup of children who had not received paralytics within two hours. At early timepoints, the absence of pupillary and motor responses was only predictive when those who received paralytics were excluded. Paralytic administration impacted motor more than pupil examinations, as is consistent with the greater impact of paralytics on striated muscles compared with the non-striated muscle of the pupil.

Children with prior neuro-developmental abnormalities were included in this study since they represent a substantial portion of the pediatric cardiac arrest population, including 9 of 35 subjects in the current study. Similar patients have been included previously in the pediatric cardiac arrest literature utilizing the PCPC as the outcome measure (24–26).

This study has multiple limitations. First, only short-term (ICU discharge) outcome was assessed and therefore we cannot determine if early exams prognosticate long term outcomes. Some patients may have improved after discharge and future studies of prognosis will need more detailed outcome evaluation over a longer period. Second, outcome was determined by using PCPC scores at the time of ICU discharge, and not by detailed neurological and neuropsychological testing after extended follow-up. While PCPC is easy to assess, it is not robust for evaluating children younger than school age or for evaluating interval change in children with baseline neurodevelopmental disabilities. Further, deficits are not categorized by domain as accomplished by some newer outcome measures (22). Despite these limitations, the PCPC has been utilized as a pre-morbid and post-morbid measure in the pediatric cardiac arrest literature to date and is part of the Utstein Critieria (23). Third, although the intensivists caring for these patients were discouraged from making treatment decisions based on these potentially unreliable examination abnormalities, it is still possible that their decisions were influenced by this knowledge. If patients with absent motor and papillary responses received less aggressive care or withdrawal of their technological support, this could lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy in which signs believed to predict a poor outcome actually produced the poor outcome. Fourth, this study only included 35 children, and some were excluded from examination at some timepoints due to paralytic administration. This enrollment number was dictated by a change in the clinical hypothermia protocol, such that future subjects could not be combined with the current cohort. Critical care pathways are likely to continue to change and improve with ongoing research, and this may preclude enrollment of sufficient patients managed in a similar manner to permit large studies to be performed at a single center. Finally, it cannot be determined whether the early assessment is less predictive than later assessments due to confounding from hypothermia or simply because the hypothermia exam falls earlier during the treatment course and earlier examinations are less predictive than later examinations. Early hypothermia pupillary and motor exams were performed before 24 hours and therefore, it is unclear whether the poor prognostic value is due to timing of examination or temperature. We did not have normothermic controls to compare with our hypothermic subjects at identical timepoints and thus, were unable to control for temperature versus time.

CONCLUSIONS

This single center prospective cohort study of children managed with therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest demonstrated that absent motor and pupil responses immediately following resuscitation or during hypothermia were not predictive of unfavorable short-term outcome, while absent motor and pupil responses later during the course, during normothermia, were predictive of unfavorable short-term outcome. However, these signs were only predictive of more broadly defined unfavorable short-term outcome (PCPC 4,5,6) and not of death. Further study is needed to determine whether TH improves outcome in children after CA and what variables, alone or collectively, best predict outcome. Models utilizing the results of physical examination, biomarkers, neurophysiologic testing, and neuroradiologic data may be more informative and permit earlier and more precise prognostication than any modality in isolation, but will likely require a multi-center effort to enroll sufficient patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work is supported by grants from the Penn Alliance for Therapeutic Hypothermia (University of Pennsylvania Neuroscience Center), the University of Pennsylvania Clinical Trials Research Center Grant (UL1-RR-024134 to Drs. Topjian and Nadkarni), and the NINDS Neurological Sciences Academic Development Award (NSADA) NS049453 to Drs. Abend and Kessler.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young GB. Clinical practice. Neurologic prognosis after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):605–611. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0903466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abend NS, Licht DJ. Predicting outcome in children with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9(1):32–39. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000288714.61037.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, et al. Practice parameter: prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67(2):203–210. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227183.21314.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel R, Martinot A, Delepoulle F, et al. Prediction of outcome after hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a prospective clinical and electrophysiologic study. J Pediatr. 2002;141(1):45–50. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratton SL, Jardine DS, Morray JP. Serial neurologic examinations after near drowning and outcome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148(2):167–170. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170020053008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter BG, Butt W. A prospective study of outcome predictors after severe brain injury in children. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(6):840–845. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beca J, Cox PN, Taylor MJ, et al. Somatosensory evoked potentials for prediction of outcome in acute severe brain injury. J Pediatr. 1995;126(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Thenayan E, Savard M, Sharpe M, et al. Predictors of poor neurologic outcome after induced mild hypothermia following cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1535–1537. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334205.81148.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abend NS, Topjian A, Ichord R, et al. Electroencephalographic monitoring during hypothermia after pediatric cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2009;72(22):1931–1940. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a82687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiser DH, Long N, Roberson PK, et al. Relationship of pediatric overall performance category and pediatric cerebral performance category scores at pediatric intensive care unit discharge with outcome measures collected at hospital discharge and 1- and 6-month follow-up assessments. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(7):2616–2620. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth CM, Boone RH, Tomlinson G, et al. Is this patient dead, vegetative, or severely neurologically impaired? Assessing outcome for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2004;291(7):870–879. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.7.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Group. HACAS. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9460):663–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink EL, Clark RS, Kochanek PM, et al. A tertiary care center's experience with therapeutic hypothermia after pediatric cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(1):66–74. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c58237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topjian A, Hutchins L, Diliberto M, et al. Induction and maintenance of therapeutic hypothermia after pediatric cardiac arrest: efficacy of a surface cooling protocol. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e28717. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fink EL, Kochanek PM, Clark RS, et al. How I cool children in neurocritical care. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12(3):414–420. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossetti AO, Oddo M, Logroscino G, et al. Prognostication after cardiac arrest and hypothermia: a prospective study. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(3):301–307. doi: 10.1002/ana.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman WD, Barrett KM, Biewend ML, et al. Predictors of poor neurologic outcome after induced mild hypothermia following cardiac arrest. Neurology. 2009;73(12):997–998. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181af0c42. author reply 998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. Functional Status Scale: new pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):e18–e28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaritsky A, Nadkarni V, Hazinski MF, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of pediatric advanced life support: the pediatric Utstein style. A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Heart Association, and the European Resuscitation Council. Pediatrics. 1995;96(4 Pt 1):765–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meaney PA, Nadkarni VM, Cook EF, et al. Higher survival rates among younger patients after pediatric intensive care unit cardiac arrests. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2424–2433. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. Jama. 2006;295(1):50–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samson RA, Nadkarni VM, Meaney PA, et al. Outcomes of in-hospital ventricular fibrillation in children. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2328–2339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]