Abstract

Purpose

Our goal was to determine if symptom-based ovarian cancer screening was feasible in a primary care clinic and acceptable to women and practitioners. In addition, we wanted to describe the outcomes for a pilot group of screened women.

Methods

A prospective study of 2262 women over age 40 with at least one ovary participated in symptom-based screening using a symptom index (SI). The first 1001 were in a non-intervention study arm and 1261 were screened for symptoms and referred on to testing with CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) if the SI result was positive. Patients and practitioners were surveyed about acceptability of study procedures. All patients were linked to the Western Washington SEER Cancer Registry to determine if ovarian cancer was diagnosed in any women.

Results

Of the eligible women visiting the clinic, 72.5% were interested in participating, and the participation rate was 62.1%. Of the 1261 who participated in the screening arm 51(4%) were SI positive and 47 participated in CA125 (45/47 normal) and TVS (32/47 normal). Two endometrial biopsies and one hysteroscopy D&C were performed secondary to study enrollment (pathology negative). No laparotomies or laparoscopies were performed secondary to study involvement. A survey of patient acceptability, on a scale of 1–5, revealed a mean score of 4.8 for the acceptability of SI screening and 4.7 for TVS and CA125 testing among SI positive women. Providers also rated the SI procedures highly acceptable with a mean score of 4.8. Two participating patients were diagnosed with ovarian cancer; one had a true positive SI in the non-intervention arm and one had a false negative SI in the screened arm.

Conclusion

While our pilot study is not large enough to assess sensitivity or specificity of a symptom-based screening approach, we did find that this type of screening was feasible and acceptable at the time of a primary care visit and referred approximately 4% of women for additional diagnostic testing. Symptom-based screening also resulted in minimal additional procedures.

Introduction

Currently ovarian cancer screening using the CA125 blood test and transvaginal sonography (TVS) is not recommended for average risk women. The US Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) gives these a grade “D” recommendation because there is fair evidence to recommend their exclusion from a periodic health exam because more women are harmed by false positive screening then benefit from early detection.[1]

Results from the Prostate Lung Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) Screening Trial have shown that annual CA125 and TVS each have a positive predictive value for ovarian cancer of under 5%.[2] In addition, this study reported that this screening strategy showed no difference in mortality rates for screened vs. unscreened asymptomatic women.[3] Recent reports from the UK Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial are more encouraging, they have shown that a multimodality screen that involves evaluating CA125 first and evaluating trends over time followed by ultrasound has a sensitivity of 89% with a positive predictive value of detecting ovarian cancer of over 40%.[4] Unfortunately, the screening algorithm used in this trial is quite complex. In addition, given an annual incidence of 40 per 100,000 in women over age 50, even a perfect screening test would require 2,500 women be screened for every cancer detected, making the development of a cost effective test a significant challenge.[5,6] However, if ovarian cancer can be identified in early stages or even when an optimal cytoreduction (all visible cancer is removed) can be performed, survival is significantly improved.[7,8]

Recently we have developed a symptom index (SI) as a possible low cost method of identifying women a risk of ovarian cancer.[9] The SI is considered positive if patients report experiencing any one of 6 symptoms (bloating, increased abdominal size, pelvic or abdominal pain, difficulty eating, feeling full quickly) and the symptom occurs more than 12 times per month and has been present for less than one year. In a case control study in women over 50 we found that the SI had a sensitivity of 86.7% for detecting ovarian cancer. In addition, only 1.4% of women over 50 without ovarian cancer tested positive.[9] The results from this study suggested that using symptoms as an initial ovarian cancer screen to recommend additional diagnostic testing may be an interesting approach to early detection. While there have been no prospective trials evaluating the potential impact of screening women with a symptom-based approach, many mainstream media outlets are encouraging women to keep symptom diaries and to discuss the possibility of TVS and CA125 if symptoms are present. There has been concern raised that this type of screening would result in an increase in invasive procedures and increased difficulty for providers caring for these women.

The goal of the current study was to assess the feasibility of symptom triggered ovarian cancer screening in a large primary care clinic. We sought to determine the acceptability of this type of screening with patients and providers. In addition, we wanted to describe the test results and any procedures that were performed as a result of screening using this method.

Methods

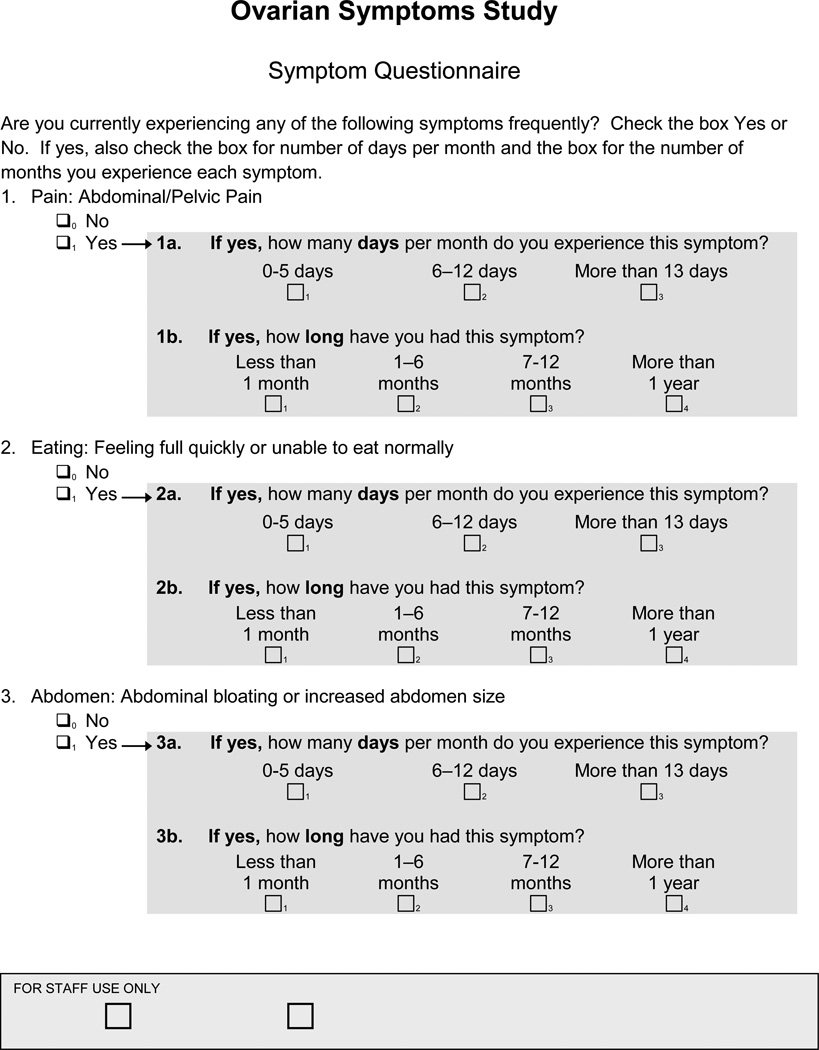

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Washington and by the IRB of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC). Women age 40 and older attending the Women’s Health Clinic at the University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC) were approached by a research nurse to determine eligibility and interest in participating in a research trial to evaluate symptoms as a possible screening tool for ovarian cancer. This clinic is one of three main primary care clinics of UWMC, serving the local community and provides approximately 20,000 visits to 9,000 women annually. The clinic provides primary care and specialty services. It is staffed by eight internists, six general ob/gyns, and six ARNPs. It is one of the three main primary care clinics of the UWMC. Women were eligible if they were 40 years of age or older, had at least one ovary and were not pregnant. Those interested in participating signed informed consent, filled out a baseline health questionnaire with demographic and health history information, and filled out a symptom index assessment form (Figure 1). The SI has been previously validated in other studies.[10] The nurse determined the scores of the SI as positive as previously described or negative. Physicians in the clinic were informed of patient participation, but were told not to alter their clinical practice in any way and thus ordered CA125 tests or pelvic ultrasounds as needed for clinical purposes. If the SI was negative no tests were ordered by the study. If the SI was positive, women were offered a CA125 and TVS as part of the study and any subsequent procedures were coded as related to the study. If the SI was positive and the patient’s primary care physician had ordered a CA125 or TVS as part of routine care, we recorded the information as part of our study, but any subsequent procedures that resulted from that testing were coded as not study related. . Patients and providers were informed of the results of the study ordered diagnostic tests and the women with abnormal results were managed according to standard of care by their physicians.

Fig. 1.

Ovarian Cancer Symptom Questionnaire

All TVS were performed in the radiology department at the clinic by a trained sonographer and radiologist as they would be for routine clinical care. Radiologists knew patients had a positive SI and so there was special focus on the ovaries, but no specific protocol was used nor was Doppler. TVS was considered normal if uterus, adnexa and ovaries were normal with no ascites or other abnormalities. CA125 was considered normal if less than 35 U/mL.

Patients were surveyed about the acceptability of the study procedures, questionnaire and study ordered diagnostic testing if indicated. Surveys were performed after completion of study procedures. For those who had a CA125 and TVS, surveys were mailed after the women had completed their testing. All responses to questions were on a 5-point scale. Clinicians and staff were also anonymously surveyed at the completion of the study about the acceptability and usefulness of the study procedures as well as the additional time, if any, of having patients participate.

Eight months after study completion, all participant names (positive and negative SI) were linked to the Western Washington SEER database to assess if any of the participants developed ovarian cancer. Sufficient time was allowed to be certain that all ovarian cancer cases were captured. The Western Washington SEER registry has a reporting population of over 3.9 million people, which is approximately 70% of the Washington State population. All of the surrounding counties served by the Women’s Health Care Clinic are part of the SEER reporting population (CSS) (www.seer.cancer.gov). The Western Washington SEER group is known as the Cancer Surveillance Service (CSS) and has been found to reliably identify more than 99% of women in its 13 county recruitment area. Over 99% of cases are entered with 6 months of diagnosis. Use of CSS assured us access to a comprehensive listing of cancer patients, thus providing data on women who were diagnosed with cancer after completing a SI, including women who received a negative result and did not have further interactions with study staff.

Statistical Methods

STATA statistical software package (version 10.0, State Corporation, College State, TX) was used for analyses. Descriptive statistics characterizing the study population included calculation of the median and range for continuous variables and the frequency and percentiles for categorical variables. Associations between patient characteristics and the results of the SI were assessed using the Chi Square and Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests were two-sided and considered to be statistically significant at p≤0.05.

Results

There were 2,262 women who participated in the study. The first 1,001 were a non-intervention group that was used to pilot our recruitment, technical usability of survey instruments, and flow within the clinic. The initial patients were enrolled from 4/08 – 9/08. These patients filled out a baseline questionnaire and a SI but did not get referred on for CA125 or TVS if the SI was positive. These patients were identified in the SEER database at the end of the study to determine if any had developed ovarian cancer. Once our study protocol was finalized we then enrolled 1,261 women in the intervention portion of the trial. These patients were enrolled from 9/08 – 7/09. For this portion women with a positive SI were offered a CA125 and TVS and their medical records were accessed to determine if any additional testing or procedures were performed as a result of women participating in the study.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of our patient population. Overall, 62% were over age 50 and 58% were postmenopausal. The majority (88%) were Caucasian and most were visiting the primary care clinic for routine screening or follow-up. The concurrent gynecologic and medical conditions that our participants suffered are also listed in Table 1. Approximately 10% of participants had fibroids and 9% had more than one gynecologic condition. The most common medical conditions were hypertension (6%), thyroid disorders (5%) and acid reflux, with 31% having more than one medical condition.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and results of the Symptom Index.

| Patient Characteristic and Health Condition |

Total* (n=1,261) |

Negative SI** (n=1,210) |

Positive SI** (n=51) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.08 | |||

| 40–49 | 412 (33%) | 389 (94%) | 23 (6%) | |

| 50+ | 784 (62%) | 757 (97%) | 27 (3%) | |

| Menopausal Status | ||||

| Pre | 285 (23%) | 269 (94%) | 16 (6%) | 0.34 |

| Peri | 181 (14%) | 173 (96%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Post | 730 (58%) | 704 (96%) | 26 (4%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1,113 (88%) | 1,068 (96%) | 45 (4%) | 0.06 |

| Black | 34 (3%) | 30 (88%) | 4 (12%) | |

| Asian | 54 (4%) | 53 (98%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Reason for Visit | ||||

| Routine screen | 696 (55%) | 682 (98%) | 14 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Routine follow-up | 158 (13%) | 154 (97%) | 4 (3%) | |

| I’m concerned about something | 310 (25%) | 282 (91%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Gynecologic Conditions | ||||

| Endometriosis | 20 (2%) | 20 (100%) | 0 | 0.07 |

| Fibroids | 124 (10%) | 118 (95%) | 6 (5%) | |

| Ovarian cysts | 77 (6%) | 74 (96%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Other gynecologic problems | 77 (6%) | 73 (95%) | 4 (5%) | |

| More than 1 of these conditions | 118 (9%) | 104 (88%) | 14 (12%) | |

| Medical Conditions | ||||

| Irritable bowel disease | 29 (2%) | 29 (100%) | 0 | 0.20 |

| Urinary tract infections | 23 (2%) | 22 (96%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Acid reflux | 59 (5%) | 58 (98%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Diabetes | 15 (1%) | 15 (100%) | 0 | |

| Hypertension | 74 (6%) | 72 (97%) | 2 (3%) | |

| Heart disease | 6 (<1%) | 6 (100%) | 0 | |

| Thyroid disease | 64 (5%) | 63 (98%) | 1 (2%) | |

| More than 1 condition | 387 (31%) | 360 (93%) | 27 (7%) |

Percentage calculated using column totals and may not add up to 100% due to missing data.

Percentage calculated using row totals.

Overall, 4% (51 women) of participants had a positive SI. We found that significantly more women presenting for a problem visit had a positive SI than those coming in for routine exams. We did see a trend towards older women having lower rates of a positive SI result compared to younger women; 3% women age 50+ vs. 6% women age 40–49 (p=.08). African American women had a trend toward higher positive SI rates, 12% vs. 4% for Caucasians (p=0.06), and women with multiple gynecologic conditions also trended toward higher positive SI rates. None of these trends were statistically significant but might be in a larger study population.

Of the 51 women with a positive SI 47 (92%) participated in CA125 and TVS screening. Of the 47 CA125s, 45 were less than 35 U/mL, one CA125 was 36 U/mL (normal TVS) and one was 42 U/mL (TVS showed small complex cyst, likely endometrioma). In the later patient the CA125 was repeated 3 months later because of the study and was 26 U/mL. Repeat TVS showed the cyst to be stable. Of note, 4/47 CA125s and 17/47 TVS were ordered by physicians as part of routine care. Of the 47 TVS performed 32 were normal and 15 were abnormal. Table 2 shows the results of the abnormal TVS and any subsequent studies or tests performed. Four repeat TVSs were performed to follow up on abnormalities found on a study TVS. Two endometrial biopsies and one hysteroscopy D&C were performed secondary to finding a thickened endometrial stripe on the TVS. None of the three biopsies had abnormalities. One patient did undergo a TAH BSO for treatment of painful endometriosis; however, this was performed as part of routine care. No patients underwent a laparotomy or laparoscopy as a result of study participation.

Table 2.

Summary of abnormal ultrasound results and additional procedures.

| US Results | CA125 | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Fibroids, normal ovaries | 15 | None |

| Endometrial polyp, normal ovaries | 8 | D&C Hysteroscopy |

| Complex right ovarian cyst | 5 | TAH-BSO for endometriosis* |

| Fibroids, complex right ovarian cyst | 6 | Pelvic ultrasound, cyst resolved |

| Fibroids, small complex left ovarian cyst | 15 | Pelvic ultrasound, cyst resolved |

| Fibroids, normal ovaries | 10 | None |

| Thickened endometrial stripe | 5 | Endometrial biopsy |

| Complex bilateral ovarian mass | 42 | Repeat CA125=26, pelvic ultrasound, stable endometriomas* |

| Small bilateral ovarian cysts | 9 | Pelvic ultrasound, cyst stable |

| Possible polyp, normal endometrial strip | 15 | None, patient asymptomatic |

| Probable hydrosalpinx | 7 | CT scan for abdominal symptoms* |

| Endometrial polyp, normal ovaries | 16 | Endometrial biopsy |

| Large fibroid, uterus normal, normal ovaries | 9 | CT scan* |

| Fibroids, simple right ovarian cyst | 5 | None |

| Complex right ovarian cyst | 5 | Pelvic ultrasound, decreasing size of cyst. |

Performed as part of routine clinical care

Table 3 shows the acceptability of the symptom based screening for women with a negative (N=1210) or a positive SI (N=51); not all women returned the survey or answered all of the questions. Overall, there was a very high level of acceptability for this type of screening. On a scale of 1–5 (1=not at all, 5=very much) the mean acceptability of symptom screening was 4.8 for those with negative SI result and 4.7 for those with a positive SI result. Table 4 shows the rating for the acceptability of the CA125 and TVS tests among those who participated in testing (27 of the 47 women returned the survey). The mean overall acceptability score was 4.7. Table 5 shows the results of the survey of provider acceptability of study activities. Overall provider acceptability was 4.8 and providers did not indicate that this screening significantly increased the time for patient visits.

Table 3.

Summary of results of acceptability for those with a negative SI and positive SI

| Negative SI (n=1,210) |

Positive SI (n=51) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | Mean (SD) or %* |

#2 | Mean (SD) or %* |

p- value |

|

| How acceptable were the symptom questions? | 223 | 4.8 (0.53) | 44 | 4.7 (0.73) | 0.29 |

| Was the SI difficult to complete? | 1148 | 1.2 (0.58) | 44 | 1.2 (0.51) | 0.99 |

| Did any of the questions make you feel uncomfortable? | 1145 | 1.0 (0.27) | 45 | 1.2 (0.53) | 0.001 |

| How long did it take to complete (minutes)?** | 1141 | 1.5 (2.10) | 45 | 3.1 (2.9) | 0.001 |

| Did completing the survey help you communicate with your doctor? (results excludes patients who reported they didn’t have concerns) | 632 | 1.4 (1.80) | 29 | 4.6 (0.2) | 0.001 |

| Are you satisfied with the nurses’ feedback? | 1140 | 4.9 (1.20) | 45 | 4.9 (0.38) | 0.99 |

| How satisfied were you with the results? | 219 | 4.8 (0.50) | 39 | 4.6 (0.68) | 0.03 |

| How important do you think ovarian cancer screening is for women at average risk? | 224 | 4.9 (0.44) | 44 | 4.8 (0.50) | 0.18 |

| Did you find this information reassuring? | 1131 | 4.4 (1.5) | X2 | X2 | X2 |

| Percentage of patients allowing the RN to contact them regarding their answers. | 1090 | 98% | 42 | 95% | 0.44 |

Likert scale range: 1= Not at all to 5=Yes, very much

Likert scale range: 0=less than one minute; 1=one minute; 2=two minutes; 3=three minutes; 4=four minutes; 5=five minutes; 9=more than 5 minutes

Number answering question

Participants not asked this question

Table 4.

Summary of screening acceptability questionnaire results for women in whom additional testing was recommended.

| Screening Acceptability Form Questions | # | Mean (SD) or %* |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, I allowed my blood to be drawn | 27 | 96% |

| Yes, I had an ultrasound | 27 | 93% |

| Did the blood draw make you feel uncomfortable? | 21 | 1.1 (0.30) |

| Did the ultrasound make you feel uncomfortable? | 20 | 2.3 (1.3) |

| Overall, how satisfied were you with the testing process? | 27 | 4.7 (0.47) |

| How satisfied were you with the general level of care at your visit? | 27 | 4.7 (0.61) |

| How satisfied were you with the results you received? | 27 | 4.6 (0.69) |

| May we contact you regarding your responses above? | 27 | 96% |

Likert scale range: 1=Not at all to 5=Yes, very much.

27 of the 47 patients responded.

Table 5.

Provider acceptability of symptom based screening for ovarian cancer

| (n=16) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Survey Question | # | Mean (SD) |

| How acceptable did you find a symptom survey for ovarian cancer in your practice?* | 16 | 4.8 (0.58) |

| How much additional time would you estimate that the symptom survey added to patient visit?** | 14 | 2.1 (1.6) |

| What percentage of patients would you estimate required additional time?*** | 11 | 1.4 (0.67) |

| How often did you order the diagnostic test (CA125 or TVS) despite a negative symptom survey?*** | 10 | 0.40 (0.70) |

| How satisfied were you with the results you received from the symptom survey?* | 9 | 4.2 (1.1) |

| How satisfied were you when patients had a negative survey?* | 8 | 3.1 (1.6) |

| How satisfied were you when patients had a positive survey?* | 8 | 2.9 (1.5) |

| In patients with a positive index, how satisfied were you with the referrals for additional diagnostic studies?* | 8 | 3.6 (1.8) |

| How satisfied were you with the results of those diagnostic studies?* | 8 | 3.4 (1.7) |

| Do you feel that this type of symptom information is useful to your practice?* | 12 | 4.5 (0.80) |

| How important do you feel that some form of screening for ovarian cancer is offered to women who are at average risk for disease?* | 15 | 4.4 (0.74) |

Likert scale: 1=Not at all to 5+Yes, very

0=None, 1-1 min; 2=2 min; 3=3 min; 4=5 min; 5=6 or more min

0=none; 1=10%; 2=25%; 3=50%; 4=75%; 5=90% or more

In May of 2010, eight months after study completion, the Western Washington SEER database was queried for cancer results, specifically ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers. We include the first 1,001 patients who completed the SI but for whom SI results did not lead to screening and the 1,261 women that participated in the study’s screening arm. Two women were found to have ovarian cancer. One participant from the non-intervention arm had a positive SI and was diagnosed three months later with Stage III ovarian cancer. One patient in the intervention arm had a negative SI and several weeks later was found to have a stage I ovarian cancer at the time of a hysterectomy for postmenopausal bleeding, pelvic mass, and high-risk family history. This patient had a known asymptomatic pelvic mass at the time she participated in the study.

Discussion

Historically, ovarian cancer has been called a “silent killer” because symptoms were not thought to occur until advanced stages when chances of cure were poor. Recent studies have shown that the majority of women with ovarian cancer will have symptoms prior to diagnosis.[11–21] Importantly, over 80% of those with early stage disease who have an excellent chance for cure, will experience symptoms. [11–22] Unfortunately, the symptoms of ovarian cancer are vague and include bloating and abdominal or pelvic pain which can be presenting symptoms for many other diseases. Concerns have been raised that recall bias may affect symptom reporting of cancer patients as compared with controls; however, case control studies using chart review and diagnosis coding for billing prior to the diagnosis of ovarian cancer have also been conducted and confirm that cases are much more likely to experience target symptoms up to six months prior to diagnosis as compared to controls.[14,16,20] These studies suggest that there is a window of time in which an earlier diagnosis of ovarian cancer can be made with the potential for a better prognosis.

In our initial case control study of 149 women with ovarian cancer and 233 controls who were in an ovarian cancer early detection program, we evaluated the performance of the SI and found that the SI was positive in 57% of women with early stage cancer and 80% of women with advanced stage cancer.[9] In a retrospective analysis, only 2.6% of women from a primary care clinic tested positive on the SI. While the sensitivity of the SI is not nearly as high as one would like for a screening test, the use of symptoms followed by screening with CA125 and/or TVS among those with a positive SI is potentially a low cost method to improve rates of early diagnosis for women in the general population, a group for which no screening test is recommended. In addition, we have shown in subsequent case control studies that the addition of tumor markers CA125 and HE4 can significantly improve the sensitivity of the SI such that a combination of any of the three markers being positive (SI, CA125, HE4) can identify 90% of early stage and 97% of late stage ovarian cancer.[22,23] In addition, we have found that if we require two of the three markers to be positive we have a sensitivity of 83.8% and a specificity of 98.5% for detecting ovarian cancer.[23] Other investigators have found lower sensitivity of the symptom index. In a study by Pavlik et al, only 6 of 30 patients (20%) who had undergone surgery for ovarian cancer had a positive SI, although all patients were surveyed retrospectively.[24]

As the SI had never prospectively been used in a primary care clinic population, our first goal was to determine if this type of screening would be feasible and acceptable to patients and practitioners. Potential identification of ovarian cancer through symptom screening has been controversial. Concerns have been raised that this type of screening would result in many additional tests and procedures, especially major surgery.[24–26] Therefore, our second goal was to determine if symptom triggered screening did result in excessive numbers of additional procedures that could cause morbidity. This is an important issue because in the PLCO trial 15% of patients who underwent surgery for a false positive screen suffered a major surgical complication.[3]

Overall, we found symptom triggered screening very feasible to perform in a primary care clinic. We developed a form for collecting symptom information that women found easy to complete on their own and could be done in less than five minutes by almost all patients. We also found that in most cases the SI did not add additional provider time to the clinic visit. Acceptability was assessed in both patients and providers and we did not identify any significant concerns with this screening process from either group. In the PLCO and UKCTOCS trial, patient and provider acceptability has not been formally assessed. Interestingly, we found that women with a positive SI found the instrument helped facilitate communication with their physician. It may be that this SI helps women with these vague symptoms accurately report what may be medically concerning.

One of the main drawbacks to symptom triggered screening may be the relatively low sensitivity. In our pilot study there were only 2 patients out of the 2,261 who developed cancer. With an incidence of 40/100,000 this was the expected number of cases and we will not be able to determine the sensitivity of this type of screening without significantly larger number of patients enrolled. In the PLCO trial there were 34,261 women and in the UKCTOCS there were 101,279 women assigned to screening with equal numbers of controls.[3,4] Despite the low incidence of the disease the World Health Organization characterizes ovarian cancer as a disease that would likely benefit from screening, as the cure rate for women diagnosed with early stage disease are significantly higher than for women with advanced bulky disease.[5,6]

We have found that symptom triggered screening is feasible and acceptable in a primary care clinic. Approximately 4% of women are referred on for additional testing with CA125 and TVS, which makes this type of screening significantly less costly than a strategy that uses blood testing and/or TVS on 100% of the population. In addition, we found that symptoms-based screening resulted in minimal additional procedures, allaying concerns that routine evaluation of symptoms would lead to excessive numbers of surgeries. Concerns of the sensitivity of this type of screening remain, but additional research is needed to establish adequate estimates of sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values. Combining the SI with tumor markers might also offer a cost effective and feasible method to screen women in the general population for ovarian cancer.

Research Highlights.

Symptom triggered screening is feasible and acceptable to patients and practitioners.

This type of screening refers approximately 4% of women for additional diagnostic testing

Symptom-based screening results in minimal additional invasive procedures.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant number R21NR010571 from the National Institute of Nursing Research and by a Gynecologic Cancer Foundation/Ovarian Cancer Research Foundation Grant for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Nursing Research or other foundations.

References

- 1.US Preventive Services Task Force Agency for healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Screening for Ovarian Cancer, Topic Page. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Partridge E. Results from 4 rounds of ovarian cancer screening in a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:775–782. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819cda77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2295–2303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Hallett R, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):327–340. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menon U, Jacobs IJ. Ovarian cancer screening in the general population. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:61–64. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs IJ, Menon U. Progress and challenges in screening for ovarian cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:355–366. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400006-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Phase III randomized trial of intravenous cisplatin and paclitaxel versus an intensive regimen of intravenous paclitaxel, and intraperitoneal paclitaxel in stage III ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:334–343. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1248–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher SW, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109:221–227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe KA, Andersen MR, Urban N, Paley P, Drescher CW, Goff BA. The temporal stability of the Symptom Index among women at high-risk for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, Melancon CH. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2000;89:2068–2075. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001115)89:10<2068::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, Muntz HG. Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA. 2004;291:2705–2712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlin SM, Diehr PH, Andersen MR, Goff BA, Tyree PT, Lafferty ME. Identification of ovarian cancer symptoms in health insurance claims data. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:381–389. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton W, Peters TJ, Bankhead C, Sharp D. Risk of ovarian cancer in women with symptoms in primary care: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vine MF, Calingaert B, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM. Characterization of prediagnostic symptoms among primary epithelial ovarian cancer cases and controls. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith LH, Morris CR, Yasmeen S, Parikh-Patrl A, Cress RD, Romano PS. Ovarian cancer: can me make the clinical diagnosis earlier? Cancer. 2005;104:1398–1407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson SH, Mignone L, Nakraseive C, Caputo TA, Barakat RR, Harlap S. Symptoms of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:212–217. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yawn PB, Barrette BA, Wollan PC. Ovarian cancer: the neglected diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1277–1282. doi: 10.4065/79.10.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behtash N, Ghayouri Azar E, Fakhrejahani F. Symptoms of ovarian cancer in young patients 2 years before diagnosis, a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engle) 2008;17:483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freidman GD, Skilling JS, Udaltsove NV, Smith LH. Early symptoms of ovarian cancer: a case-control study without recall bias. Fam Pract. 2005;22:548–553. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MK, Kim K, Kim SM, et al. A hospital-based case control study of identifying ovarian cancer using a symptom index. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009;20:238–242. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2009.20.4.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen MR, Goff BA, Lowe KA, et al. Combining a symptoms index with CA125 to improve detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(3):484–489. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen MR, Goff BA, Lowe KA, et al. Use of a symptom index, CA125, and HE4 to predict ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(3):378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavlik EJ, Saunders BA, Doran S, et al. The search for meaning – symptoms and transvaginal sonography screening for ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:3689–3698. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox R. Commentary: diagnosing ovarian cancer, more problems than answers. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cass I. The search for meaning – symptoms and transvaginal sonography screening for ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:3606–3609. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]