Abstract

Community-dwelling HIV/AIDS patients in rural Alabama self-monitored (SM) daily HIV risk behaviors using an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system, which may enhance reporting, reduce monitored behaviors, and extend the reach of care. Sexually active substance users (35 men, 19 women) engaged in IVR SM of sex, substance use, and surrounding contexts for 4–10 weeks. Baseline predictors of IVR utilization were assessed, and longitudinal IVR SM effects on risk behaviors were examined. Frequent (n = 22), infrequent (n = 22), and non-caller (n = 10) groups were analyzed. Non-callers had shorter durations of HIV medical care and lower safer sex self-efficacy and tended to be older heterosexuals. Among callers, frequent callers had lost less social support. Longitudinal logistic regression models indicated reductions in risky sex and drug use with IVR SM over time. IVR systems appear to have utility for risk assessment and reduction for rural populations living with HIV disease.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, IVR self-monitoring, Alcohol and drug use, Risky sex

Introduction

HIV rates have been declining or stabilizing for many populations and geographic regions in the United States. In the Southeastern United States, however, HIV incidence and prevalence have been rising, particularly among persons of color [1]. Seven states with the 10 highest AIDS rates in the U.S. are located in the South, and in 2002–2006, two-thirds of all persons living with HIV/AIDS were residing in the South [2]. Proportionally greater increases in Southeastern HIV prevalence have been found for persons living in rural versus suburban or urban population centers [3]. Geographic isolation and poverty contribute to the endemic lack of medical and mental health care in the rural South, even in relation to their Southern urban counterparts [1, 4]. Alternative lifestyles associated with HIV disease remain highly stigmatized in this region.

Most research on HIV transmission patterns and effective HIV interventions has been conducted in urban and suburban settings [5], and findings may not generalize well to rural minority populations with limited economic resources and different social networks. Relatively little is known about risk and protective behavior patterns among rural HIV populations, including patterns of substance use, sexual practices, and associated social and economic contexts, or about rural high risk groups that engage in multiple risk behaviors such as substance use, unprotected sex, and transactional sex. This information is essential for the development of targeted treatment and prevention programs across the spectrum of HIV intervention opportunities that are population sensitive and specific.

Sound measurement of HIV-relevant risk, protective, and contextual factors is fundamental to the development of effective risk reduction programs for rural risk groups. Automated telephone-based Interactive Voice Response (IVR) systems have been used effectively with a wide range of at-risk community and medical patient groups and appear promising for use with rural, disadvantaged persons living with HIV/AIDS [6–8]. The vast majority of the U.S. population has phone access, including in rural areas, and IVR systems offer a telecommunications platform that can reach from the clinic into the community to expand the reach of care at relatively lower cost than face-to-face (FTF) intervention programs.

IVR systems can be made available over long periods and are well suited for use with chronic conditions like HIV/AIDS for health and risk monitoring, relapse prevention, and rapid treatment re-entry when needed. Caller responses are private, and IVR systems are well received by end-users, who often provide more complete reports of sensitive information to IVR systems compared to FTF interview methods [6–8]. Event-level IVR data can be collected prospectively to investigate sequences of risk patterns involving substance use, risky sexual practices, and the surrounding contexts [9], which remains a vital research area for effective prevention planning.

IVR self-monitoring (SM) can have beneficial reactive effects in reducing target risk behaviors, at least for a time [7,10]. Such reactive effects are undesirable for some research questions and can be minimized, e.g., by tracking multiple behaviors simultaneously and by collecting reports daily so that prior entries are not known and reports cannot be completed for a week or more at a time [6, 8, 10]. In other applications aimed at facilitating behavior change, focused self-monitoring of specific risk behaviors can serve as an assessment tool as well as function as an intervention by promoting reductions in the monitored risk behaviors [8].

These features make IVR SM appealing for use with disadvantaged persons living with HIV/AIDS in under-served rural areas with a low density of health care providers, poor transportation options, and other constraints due to poverty, low literacy, and inadequate insurance coverage. As an important first step in understanding this population’s unique risk profile and offering them appealing telehealth services, the present study provided community-dwelling HIV/AIDS patients in rural Alabama access to IVR SM for 4–10 weeks to report their substance use, sexual practices, and social and economic contextual variables related to HIV-risk. The study had two main goals: (1) to evaluate predictors of IVR engagement and utilization derived from behavioral, psychosocial, and health risk domains assessed before the start of IVR SM; and (2) to evaluate longitudinally whether engaging in IVR SM had positive reactive effects in reducing key risk behaviors over time (i.e., alcohol and drug use, risky sex).

Consistent with earlier theory and research on self-monitoring [8, 11], we viewed the IVR system as a method for self-observation that could support self-regulation of risk and protective health behaviors and promote self-care. Based on prior research [7, 10, 11], IVR utilization was expected to vary across participants, with greater utilization associated with younger age, higher education, and mastery in handling illness, including longer durations of HIV medical care and engagement in other forms of self-care and self-protection. Other individual difference variables associated with HIV risk were also evaluated on an exploratory basis, including substance use, impulsivity, social network characteristics, and self-efficacy expectations to engage in HIV protective behaviors. Longitudinal trajectories of alcohol and illicit drug use and risky sex were modeled across the IVR interval to determine if greater engagement in IVR SM had beneficial reactive effects in reducing these risk behaviors.

Methods

Sample Recruitment and Characteristics

Participants were clinic patients living with HIV/AIDS who were receiving medical care when recruited from the Health Services Center (HSC), a non-profit community-based organization that is the only provider of HIV/AIDS care in a 14-county, 9,000 square mile area in northeastern Alabama. Participants were recruited by flyers and word of mouth for a study of their risk and health behaviors using interview and telephone assessments. Eligibility criteria included: (1) age ≥ 19 years (the age of majority in Alabama); (2) reported use of alcohol or illicit drugs and sex with a partner within the past 3 months (in order to obtain sexually active substance users, the high risk target population for HIV risk reduction programs); (3) no health problems that precluded participation (e.g., dementia, psychosis); (4) were not living in the HSC Hospice or other residential facility (e.g., inpatient substance abuse treatment program) and were not taking any medication (e.g., disulfiram, methadone) that would substantially constrain opportunities for engaging in the risk behaviors of interest; and (5) had daily phone access.

About half of the 109 screened respondents were eligible, and 91.5% of those eligible (54/59) were enrolled in either an initial pilot study that involved 28 days of IVR SM (n = 8) or in the main study that involved 70 days of IVR SM (n = 46). The methods in the pilot and main studies were very similar except for the length of the IVR SM interval. Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the procedures, including sample enrollment and IVR assessment. The sample was 65% male, 43% African American, and 78% had personal incomes < $10,000/year (see Table 1). The mean age was 38.4 years (SD = 9.5), and the mean educational level was 10.9 years (SD = 2.4). Most participants were unemployed, unmarried, and heterosexual, although a sizeable minority was variously lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of sample enrollment and study procedures, including IVR protocol

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at initial assessment as a function of IVR utilization category

| Variable | Non-callers (n = 10) |

Infrequent callers (n = 22) |

Frequent callers (n = 22) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % | M | SD | % | M | SD | % | Test statistica | P | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||||||

| Male | 80.00 | 54.55 | 68.18 | χ2 (2) = 2.14 | ns | ||||||

| Female | 20.00 | 45.45 | 31.82 | ns | |||||||

| White | 60.00 | 63.64 | 40.91 | χ2 (2) = 2.48 | ns | ||||||

| Other race/ethnicity | 40.00 | 36.36 | 59.09 | ns | |||||||

| Employed full- or part-time | 20.00 | 27.27 | 22.73 | χ2 (2) = 0.24 | ns | ||||||

| Annual income < $10,000 | 80.00 | 77.27 | 77.27 | χ2 (2) = 0.04 | ns | ||||||

| Age (years) | 43.40 | 5.58 | 35.64 | 8.08 | 38.86 | 11.33 | F (2, 53) = 2.45 | 0.09 | |||

| Years of education | 9.80 | 3.05 | 10.95 | 1.94 | 11.27 | 2.37 | F (2, 53) = 0.26 | ns | |||

| Partner status and sexual orientation | |||||||||||

| Married/long-term relationship | 57.14 | 36.84 | 31.57 | χ2 (2) = 1.43 | ns | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 100.00 | 63.16 | 42.11 | χ2 (2) = 7.99 | 0.018 | ||||||

| Homosexual, bisexual, questioning or undisclosed | 0.00 | 36.84 | 42.11 | 0.018 | |||||||

| HIV/AIDS medical care (years) | 3.30 | 3.65 | 7.45 | 4.75 | 7.14 | 5.66 | F(2, 52) = 2.72 | 0.08 | |||

| Baseline risk behaviors (TLFBb) | |||||||||||

| % drinking days | 19.00 | 21.00 | 15.00 | 19.00 | 17.00 | 22.00 | F (2, 53) = 0.11 | ns | |||

| M quantity/drinking day (ml ethanol) | 19.15 | 21.19 | 18.28 | 29.66 | 13.67 | 18.77 | F (2, 53) = 0.27 | ns | |||

| % days involving other drug use | 4.00 | 5.00 | 23.00 | 32.00 | 22.00 | 29.00 | F (2, 53) = 1.81 | ns | |||

| % days involving partner sex | 10.00 | 10.00 | 19.00 | 22.00 | 20.00 | 30.00 | F (2, 53) = 0.73 | ns | |||

| % days involving risky sex | 7.00 | 9.00 | 13.00 | 23.00 | 12.00 | 22.00 | F (2, 53) = 0.37 | ns | |||

| Time sensitivity measures | |||||||||||

| CFCc (60)d | 34.75 | 5.15 | 37.42 | 7.52 | 39.05 | 7.18 | F (2, 48) = 1.12 | ns | |||

| ZTPIe present-hedonistic score (5.1) | 3.55 | 0.38 | 3.50 | 0.55 | 3.16 | 0.64 | F (2, 48) = 2.35 | 0.10 | |||

| ZTPIe future score (5.2) | 3.12 | 0.45 | 3.31 | 0.62 | 3.38 | 0.64 | F (2, 48) = 0.59 | ns | |||

| Delay discounting k-parameterf | −4.27 | 1.96 | −4.51 | 1.98 | −3.69 | 2.27 | F (2, 49) = 0.80 | ns | |||

| Social network characteristics (NSSQg) | |||||||||||

| Total social contact | 55.00 | 49.05 | 53.25 | 44.19 | 69.64 | 46.45 | F (2, 47) = 0.56 | ns | |||

| Total network support | 174.86 | 175.43 | 174.68 | 130.88 | 214.91 | 116.89 | F (2, 48) = 0.73 | ns | |||

| Support lost during past year (4) | 1.14 | 1.95 | 1.79 | 1.75 | 0.62 | 1.24 | F (2, 46) = 2.76 | 0.07 | |||

| HIV-related self-efficacy expectations forh | |||||||||||

| Condom use (4) | 3.91 | 0.16 | 3.89 | 0.56 | 3.52 | 0.79 | F(2, 44) = 0.32 | ns | |||

| Disclosure of HIV status (5) | 3.11 | 0.90 | 3.28 | 0.99 | 2.79 | 1.07 | F(2, 44) = 2.96 | .063 | |||

| Safer sex negotiation (6) | 2.86 | 0.86 | 3.59 | 0.67 | 3.45 | 0.74 | F(2, 46) = 2.60 | 0.086 | |||

Test statistics and P-values are from one-way analyses of variance or 3 × 2 Chi-square analyses comparing the non-caller, infrequent, and frequent caller groups; see Table 2 concerning group differences for variables with P < 0.10.

Timeline Followback interview.

Consideration of Future Consequences scale.

Maximum possible scores for scaled questionnaires are given in parentheses after the variable name.

Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory.

Reward k-parameters were log-transformed for analysis.

Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire; total social contact based on number, frequency, and duration of contact with support people; total network support = sum of emotional support and tangible aid.

Ratings made using the Semple et al. [20] scale

The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board and covered by a federal Certificate of Confidentiality. All participants gave written informed consent and were reimbursed using University-issued Visa™ debit cards ($35 for baseline interviews and IVR training; $15 for follow-up interviews; $25 bonus for completing all data collection [main study only]).

Interview Assessments

Initial 1.5–2.0 h individual interviews were conducted by a trained research staff member at safe community or clinic locations or at participants’ homes. An expanded Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview was used to assess drinking and other drug use [12], sexual behaviors [13], and money spent on alcohol and other commodities [14]. The TLFB uses recall aids (e.g., calendars, anchor events) to structure daily retrospective reports of risk behaviors for up to a year and has sound psychometric properties [12]. The baseline interview covered the past 3 months to verify eligibility and to assess predictors of subsequent IVR utilization. Participants were interviewed again at the end of the IVR interval covering the time elapsed since baseline to check on the consistency of IVR reports over the same period. Comparisons of IVR reports with TLFB reports matched over the same intervals generally showed good to excellent correspondence [15].

At the end of the interviews, participants completed a brief computerized delay discounting task that assessed choices among hypothetical money outcomes [16]. The task is a behavioral measure of impulsivity and provides an index (k-parameter) of the rate at which individuals devalued future rewards. Participants also completed baseline time perspective questionnaires that assessed sensitivity to future outcomes [17, 18], social network characteristics and support [19], and HIV-related self-efficacy expectations [20].

IVR Self-Monitoring

At the end of the baseline interviews, participants were trained to use the IVR system and received a workbook with the IVR questions and definitions of behaviors and events. They were assigned a personal identification number to access the system at any time using a toll-free 800 number, which was programmed using commercial software (SmartQ Version 5(5.0.141). Telesage, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC). The IVR protocol included a daily survey and a weekly survey administered each Monday. As summarized in Fig. 1, the daily survey focused on the HIV risk behaviors of interest that are reported here. The weekly survey, which will be reported elsewhere, focused on weekly income and non-cash assets received; any medical care or institutionalization; and included 7-day recall checks on daily reports of key risk and protective variables. A health educator familiar with the sample reviewed all items to assure they were educationally appropriate (pre-dominately 8th grade reading level) and culturally sensitive.

The daily survey assessed ounces of beer, wine, and liquor consumed; use of other illicit drugs or prescription drugs to “get high”; and dollars spent on alcohol and other drugs during the preceding day (defined as the 24 h period midnight-to-midnight yesterday). When no alcohol or drug use was reported, participants answered questions about other activities on the preceding day to balance call duration (e.g., recreational or social activities).

The daily survey also asked about engagement on the preceding day in any sexual activity with a partner and, if so, the type of activity (with anal, oral, or vaginal sex queried separately), type of partner with whom each sex act occurred (main, non-main, or anonymous partner), other sexual risk behaviors (e.g., exchange of sex for money or goods; whether alcohol or drugs were used before or during each sex act), and protective behaviors (e.g., use of barrier protection). A day was scored as a “risky sex day” if participants reported sexual activity with multiple or anonymous partners, substance use before or during sexual activity, unprotected sex, or exchange of money or other goods for a sex act.

On average, the daily and weekly IVR surveys were each completed in less than 5 min. To promote IVR utilization, as in prior research participants accrued points for completing daily calls that were modestly reimbursed using an “electronic bank” [21]. Participants in the pilot and main studies could receive up to $85 or $190, respectively, for 100% call compliance over their 28- or 70-day IVR intervals. Among those who called the IVR at least once, pilot and main study participants earned a mean of $20 (range = $3–43) and $41 (range = $3–103.50), respectively. Accrued bank balances were paid at the end of the pilot study and after 5- and 10-weeks of the main study. Participants could call in missed reports to a staff member, but no payments were made for delayed reports.

Data Analysis

Based on their IVR utilization patterns, enrolled participants were categorized as (1) callers (n = 44) or non-callers (n = 10), depending on whether they ever called the IVR system; and (2) among callers, whether they were frequent (n = 22) or infrequent (n = 22) callers, based on whether they did or did not complete ≥ 70% of scheduled daily calls, respectively. This cut-point was selected empirically because the biggest line of fracture in the cumulative percentage of IVR calls was between 60 and 71% (see Fig. 2); this also breaks the sub-sample of 44 callers at the median. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Chi-square tests were used to identify variables that differentiated the caller/non-caller groups and the frequent/infrequent caller groups at the P ≤ 0.10-level for further examination in a series of logistic regression analyses. Each model was restricted to one predictor and one outcome variable due to the limited sample size. Non-callers were the referent group in the first set of analyses concerned with IVR engagement, and infrequent callers were the referent group in the second set concerned with IVR utilization among the callers. Odds ratios (OR) based on a one standard deviation change in the predictor variable and associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported for continuous variables to allow direct comparisons; dichotomous variables were not z-transformed.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of scheduled calls made to the IVR system over 28- or 70-day self-monitoring intervals in the pilot and main studies, respectively. The x-axis represents each of 54 individual participants, and the y-axis is the percentage of their daily calls (0–100%)

To assess whether utilization of IVR SM over time had beneficial reactive effects in reducing risk behaviors, multi-level mixed longitudinal modeling procedures were conducted using SAS Proc Glimmix. Longitudinal trajectories were modeled separately for the three main risk behaviors of alcohol use, other drug use, and risky sexual practices using the subset of IVR callers. Each event record was treated as a statistical unit of analysis (level 1 unit), nested within each participant (level 2 unit), and the dependent variable was whether or not the risk behavior was reported on each day of IVR SM. The primary predictor variable was a time-varying cumulative indicator of how many days the participant had used the IVR SM system up to and including that particular call day. A baseline indicator of the number of days each risk behavior was reported on the initial TLFB interview (maximum possible = 89 days) was included as a time-invariant covariate (between-subjects effect). Estimates were obtained using the residual pseudo likelihood (RSPL) method, and a random effect was estimated for the level 2 intercept.

These longitudinal logistic regression models therefore predicted the likelihood of risky behavior on any given day based on (a) how many times previously each participant had called the IVR system, and (b) the frequency with which each participant had engaged in the risky behavior during the 3-months before IVR availability. If the odds ratio associated with the cumulative, time-varying, IVR call variable was significantly lower than the null value of 1.0, this indicated that the reported rate of the risky behavior decreased significantly over time as more IVR calls were made.

Results

IVR Utilization

Figure 2 presents the percentage of days that each of the 54 participants made their scheduled IVR calls, which adjusts for the different reporting intervals across the pilot and main studies. Call frequency was distributed across the entire range from 0 to 100%. Ten of 54 participants (two pilot, eight main study participants) did not start the IVR task and were categorized as non-callers; the remaining 44 participants who started IVR SM were categorized as callers. For the whole sample including callers and non-callers, the mean percentage of IVR call days was 50.2% (SD = 38.8), and the median was 42.9%. For the subset of callers (n = 44), the mean percentage of IVR call days was 61.6% (SD = 33.7), and the median was 65.7%.

Predictors of IVR Utilization

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the univariate analyses for the non-caller, infrequent, and frequent IVR caller groups. Table 2 summarizes the logistic regression results with effects P < 0.10 that compared non-callers with callers (N = 54) and infrequent callers with frequent callers, excluding non-callers (n = 44).

Table 2.

Logistic regression results to predict IVR utilization

| Baseline predictorb | Callers vs. non-callersa |

Frequent vs. infrequent callersa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age | 0.494 | 0.229–1.066 | 0.072 | 1.390 | 0.767–2.519 | ns |

| Years of HIV/AIDS medical care | 2.907 | 1.067–7.921 | 0.037 | 0.940 | 0.515–1.717 | ns |

| Self-efficacy for safe sex negotiation | 2.145 | 1.012–4.546 | 0.046 | 0.800 | 0.396–1.616 | ns |

| Lost social support (NSSQc) | 1.020 | 0.451–2.309 | ns | 0.435 | 0.209–0.906 | 0.026 |

| ZTPId present-hedonistic subscale | 0.668 | 0.301–1.486 | ns | 0.558 | 0.288–1.079 | 0.083 |

| Sexual orientation (heterosexual) | 0.208 | 0.040–1.095 | 0.064 | 0.476 | 0.142–1.593 | ns |

Referent groups were non-callers or infrequent callers (on < 70% of IVR days).

Continuous predictor variables were z-transformed to allow direct comparisons among odds ratios (OR) adjusted to indicate a one standard deviation change in the predictor variable; dichotomous variables were not z-transformed; P-values are for the associated 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Norbeck social support questionnaire.

Zimbardo time perspective inventory

Callers Versus Non-Callers

Duration of HIV/AIDS medical care (OR = 2.907, 95% CI = 1.067, 7.921, P = 0.037) and participants’ self-efficacy expectations for negotiating safer sex practices (OR = 2.145, CI = 1.012, 4.546, P = 0.046) were both significant predictors of whether participants used the IVR system. A one standard deviation increase in care duration was associated with a 2.91-fold increase in the odds of calling the IVR, and a one standard deviation increase in negotiation self-efficacy was associated with a 2.15-fold increase in the odds of calling the IVR.

Sexual orientation and age were marginally significant predictors. Being of a sexual orientation other than heterosexual was associated with a 4.81-fold increase in the odds of calling the IVR compared to heterosexuals (OR = 0.208, CI = 0.040, 1.095, P = 0.064). Compared to those who never called, participants who called the IVR at least once were younger (OR = 0.494, CI = 0.229, 1.066, P = 0.072). A one standard deviation decrease in age was associated with a 2.02-fold increase in the odds of calling. There were no significant relationships with other demographic characteristics, including gender, race, and education, or with baseline substance use, sexual practices, social network characteristics, or impulsivity/time sensitivity variables.

Frequent Versus Infrequent Callers

A non-overlapping set of variables predicted call frequency among the subset of IVR callers. The strongest predictor was the overall amount of social support lost during the past year (OR = 0.435, 95% CI = 0.209, 0.906, P = 0.026). A one standard deviation decrease in the amount of support lost was associated with a 2.30-fold increase in the odds of being a frequent IVR caller (≥ 70% call compliance). Those who reported losing less social support and whose social networks were less diminished were more likely to be frequent callers.

There also was a marginally significant association between call frequency and the ZTPI present-hedonistic subscale (OR = 0.558, CI = 0.288, 1.079, P = 0.083). A one standard deviation decrease in endorsing a present-hedonistic time perspective was associated with a 1.79-fold increase in the odds of being a frequent caller.

Changes in Risk Behaviors as an Effect of IVR SM Utilization over Time

For the subset of callers, the mixed longitudinal logistic regression models predicted the likelihood of risky behavior occurring on a given day based upon the total number of days that each IVR participant had called as of that day. The number of days that each participant reported engaging in that behavior on the baseline TLFB for the 3 months before IVR SM began was also included as a time-invariant predictor. The mean number of baseline days was 11.14, 19.16, and 13.77 for risky sexual practices, drug use, and drinking, respectively.

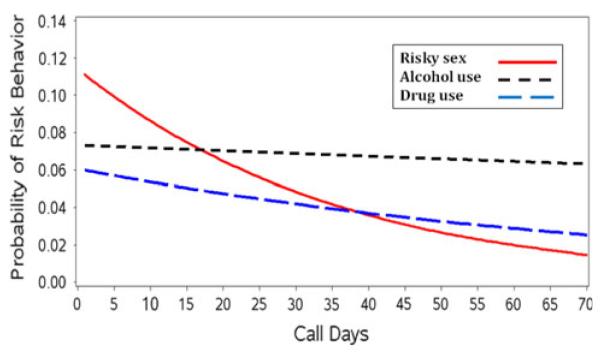

Based on these model results, risky sex and drug use other than alcohol were significantly reduced over time as more IVR SM calls were made. The odds of reporting risky sex acts decreased by 3.0% per IVR call day (OR = 0.970, 95% CI = 0.958, 0.981, P < 0.0001), and the odds of reporting illicit drug use decreased by 1.3% per IVR call day (OR = 0.987, CI = 0.977, 0.998, P = 0.014). The odds of reporting alcohol use were not significantly altered as the number of IVR call days increased (OR = 0.998, CI = 0.988, 1.007, P = 0.63). On all three variables, the TLFB frequency of behavior significantly predicted the likelihood of reporting that behavior during IVR calls (risky sex: OR = 1.037, CI = 1.006, 1.068, P = 0.018; drug use: OR = 1.033, CI = 1.008, 1.059, P = 0.009; alcohol: OR = 1.034, CI = 1.00, 1.69, P = 0.049). These effects indicate that for each additional day that a behavior was reported on the baseline TLFB, the likelihood of that behavior being reported on an IVR call day increased by approximately 3.5%.

The predicted probabilities of risky sex, drug use, and alcohol use across the IVR interval were calculated based on the longitudinal logistic regression models. Mean-centered values were used for the time-invariant baseline TLFB predictors, and the predicted probabilities displayed in Fig. 3 for each risk behavior during the IVR interval are, therefore, estimated trajectories for the “average” participant.

Fig. 3.

Predicted probabilities of each risk behavior as a function of IVR call days for IVR callers (n = 44) from longitudinal logistic regression models. Mean-centered values were used for the time-invariant baseline TLFB predictors, and the estimated trajectories are therefore for the “average” participant (see text)

Discussion

Although the appeal of the IVR system varied across participants, more than 80% of the sample used the system at least once to report HIV-related risk behaviors. Among callers, more than 60% of scheduled calls were made on average over the 4- or 10-week IVR intervals. These data supported the feasibility of IVR systems for use with disadvantaged adults living with HIV/AIDS in the rural South. Their overall utilization was similar to patterns observed for more advantaged samples [7, 14]. These findings add to evidence that IVR systems have appeal across diverse population segments, even though some individuals do not engage.

The variability in calling patterns highlights the importance of identifying predictors of IVR engagement and utilization. As predicted, participants who used the IVR system had received HIV-related medical care for more years and had higher self-efficacy for negotiating safer sex compared to those who never called. In addition to these significant effects, callers also tended to be younger and were not heterosexuals. These results suggested that patients with alternative sexual orientations who engaged in other forms of health care and self-protection also were more likely to use the IVR system.

A different set of variables predicted call frequency among the subset of IVR callers. Frequent callers had lost significantly less social support during the past year than infrequent callers. They also tended to be less impulsive, as reflected in lower scores on the present-hedonistic subscale of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory, an effect that approached conventional levels of statistical significance. Relatively stable social contexts and lower impulsivity thus appear to be conducive to more frequent IVR use.

Although the logistic regression results generally revealed a coherent profile of the kinds of rural persons living with HIV/AIDS who did and did not find the IVR system appealing, the individual measures were not uniformly significant within different predictor variable domains. Replication studies with larger samples are needed to verify the identified domains. The limited sample size made it necessary to restrict each logistic regression model to one predictor and one outcome variable in order to have a viable participant-to-variable ratio, but the large number of bivariate analyses may have increased the overall probability for a few of the findings to be spurious. However, the limited sample also provided less power to test the relationships of interest due to larger standard errors and wider confidence intervals compared to what would have been obtained for the same effect sizes in larger samples. The present results, therefore, while preliminary and conservative due to the relatively small sample size, lay an intriguing foundation for further research and application on the use of IVR systems with persons living with HIV/AIDS.

The study’s second major set of analyses used repeated-measures observations across participants to evaluate the potential reactive effects of IVR SM on key risk behaviors. These focused analyses were based on over 1,650 daily reports for the sample as a whole and showed beneficial reductions in two of three targeted risk behaviors as a function of making IVR calls. Risky sex and drug use in this HIV-positive group decreased over the IVR interval, and the decreases were positively related to the extent of IVR SM. A plausible explanation is behavioral reactivity from self-monitoring that specifically affects (i.e., reduces) the monitored behaviors, as found in other studies [7, 10]. In addition, baseline risk-taking behavior affected IVR reporting of all three risk behaviors. These effects were expected and showed that risk behavior reporting was consistent across adjacent time intervals using different data collection methods.

Alcohol use was not found to change over time due to self-monitoring. It is possible that the present participants did not view alcohol use as presenting the same degree of risk as illicit drug use and risky sexual behaviors, making alcohol use less affected by these self-monitoring and self-regulation mechanisms. Also, at least one study that observed decreases in drinking used much longer self-monitoring intervals (up to 2 years) [22]. The present findings for drinking may be due to the relatively short time-frame of active self-monitoring.

These beneficial reductions in risky sex and drug use provide compelling support for further work using IVR systems with disadvantaged rural populations at-risk for or living with HIV/AIDS. However, the present study has limitations, in addition to the modest-sized sample, that merit caution and further investigation. First, although the longitudinal models suggested beneficial reactive effects of IVR SM on drug use and risky sex, the relationships observed were correlational and warrant further study by experimentally manipulating IVR access. Absent such research, it cannot be determined unequivocally if IVR SM reduced the risk behaviors, or whether there were other possible factors, such as changes in participants’ life circumstances, that contributed to the reductions in drug use and risky sex.

Second, these results obtained with patients in a single rural clinic in the South should be generalized with caution to other rural settings and other populations of persons living with HIV/AIDS. Third, a minority of the enrolled sample did not use the IVR system much, if at all. Although some attrition and non-compliance were explained by participant circumstances (e.g., post-enrollment illness, death, moving away), predictors of IVR engagement need further study so that the service can be offered as part of an integrated assessment and intervention system to persons who will find it appealing.

Fourth, like many other IVR SM studies conducted over weeks and months [14, 21], the present study used an electronic bank to modestly reimburse participants for making scheduled IVR calls. Whether similar results would be obtained without such payments needs investigation. Clinical applications that implement IVR-based assessments and interventions as part of an integrated system of care may need to consider other incentives (e.g., vouchers or lotteries as used in Community Reinforcement Approach applications) to promote utilization and obtain more continuous outcome data.

With these qualifications, the present study supported the utility of IVR systems as a platform for delivering telehealth risk-reduction interventions to hidden and hard-to-reach populations living with or at risk for HIV disease. Phone access is nearly universal, even in rural areas, and IVR systems do not depend on caller literacy. The study suggested that IVR SM can facilitate positive changes in HIV-risk behaviors, including risky sex and drug use, even in the absence of other intervention components. IVR systems thus appear to have utility in a comprehensive risk reduction approach to HIV disease that spans medical, telehealth, and self-care applications. IVR systems can reach rural, disadvantaged, and other hidden populations living with chronic illness over long periods of time, and they can help monitor and reduce risk behaviors in such groups.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant no. 5 R21 DA21524 to Jalie A. Tucker. The authors thank Dr. Barbara Hanna, Medical Director, and the staff of the Health Services Center, Hobson City, AL for their support of project data collection, and Katharine E. Stewart for consultation on HIV-related assessment. Portions of the research were presented at the August 2008 meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA and the April 2010 meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Contributor Information

Jalie A. Tucker, Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

Elizabeth R. Blum, Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

Lili Xie, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

David L. Roth, Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

Cathy A. Simpson, Department of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

References

- 1.Southern AIDS Coalition [Accessed 18 Jan 2011];Southern States Manifesto: update 2008—HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in the south. 2008 http://www.nmac.org/index/southern-states-manifesto.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Centers for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB prevention [Accessed 18 Jan 2011];2006 Disease profile. 2008 http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/Publications/docs/2006_Disease_Profile_508_FINAL.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed 18 Jan 2011];Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in rural and urban areas of the United States in 2006. HIV/AIDS surveillance supplemental report 2008. 2008 vol. 13(2) http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2008supp_vol13no2/pdf/HIVAIDS_SSR_Vol13_No2.pdf.

- 4.Reif S, Whetton K, Ostermann J, Raper J. Characteristics of HIV-infected adults in the Deep South and their utilization of mental health services: a rural versus urban comparison. AIDS Care. 2006;18S:S10–7. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):465–76. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abu-Hasaballah K, James A, Aseltine RH., Jr Lessons and pitfalls of interactive voice response in medical research. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(5):592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder KEE, Johnson CJ. Interactive voice response technology to measure HIV-related behavior. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6(4):210–6. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker JA, Grimley DM. Public health tools for practicing psychologists. Advances in psychotherapy—evidence-based practice. vol. 20. Hogrefe & Huber; Cambridge, MA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1035–45. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horvath KJ, Beadnell B, Brown AM. A daily web diary of the sexual experiences of men who have sex with men: comparisons with a retrospective recall survey. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:537–48. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahoney DF, Tarlow BJ, Jones RN. Effects of an automated telephone support system on caregiver burden and anxiety: findings from the REACH TLC study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):556–67. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Weinhardt LS. Assessing sexual risk behavior with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:365–75. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker JA, Foushee HR, Black BC, Roth DL. Agreement between prospective IVR self-monitoring and structured retrospective reports of drinking and contextual variables during natural resolution attempts. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(4):538–42. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson CA, Xie L, Blum ER, Tucker JA. Agreement between prospective Interactive Voice Response Self-Monitoring and structured recall reports of risk behaviors in rural substance users living with HIV/AIDS. Psychol Addict Behav. doi: 10.1037/a0022725. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA. Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;6:292–305. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strathman A, Gleicher F, Boninger DS, Edwards CS. The consideration of future consequences: weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66:742–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Putting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:1271–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norbeck JS, Lindsey AM, Carrieri L. Further development of the Norbeck social support questionnaire: normative data and validity testing. Nurs Res. 1983;32(1):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. The sexual negotiation behavior of HIV positive gay and bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:934–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Searles JS, Perrine MW, Mundt JC, Helzer JE. Self-report of drinking using touch-tone telephone: extending the limits of reliable daily contact. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(4):375–82. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helzer JE, Badger JG, Rose JL, Mongeon JA, Searles JS. Decline in alcohol consumption during two years of reporting. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(5):551–8. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]