Summary

Mutations in Pkd1, encoding polycystin-1 (PC1), cause Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD). We show that the carboxy-terminal tail (CTT) of PC1 is released by γ-secretase-mediated cleavage and regulates the Wnt and CHOP pathways by binding the transcription factors TCF and CHOP, disrupting their interaction with the common transcriptional co-activator p300. Loss of PC1 causes increased proliferation and apoptosis, while reintroducing PC1-CTT into cultured Pkd1 null cells reestablishes normal growth rate, suppresses apoptosis, and prevents cyst formation. Inhibition of γ-secretase activity impairs the ability of PC1 to suppress growth and apoptosis, and leads to cyst formation in cultured renal epithelial cells. Expression of the PC1-CTT is sufficient to rescue the dorsal body curvature phenotype in zebrafish embryos resulting from either γ-secretase inhibition or suppression of Pkd1 expression. Thus, γ-secretase-dependent release of the PC1-CTT creates a protein fragment whose expression is sufficient to suppress ADPKD-related phenotypes in vitro and in vivo.

Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), a common genetic disorder, produces fluid-filled renal cysts that disrupt the normal tubular architecture and can ultimately lead to kidney failure (Wilson, 2004). Most cases (85%) result from mutations in the gene encoding polycystin-1 (Pkd1), with the remaining 15% resulting from mutations in the gene encoding polycystin-2 (Pkd2) (Harris and Torres, 2009; Rossetti et al., 2007). Polycystin-1 (PC1) has a large extracellular domain, 11 transmembrane spans, and a short carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic tail (Hughes et al., 1995). The PC1 C-terminal tail has been implicated in the regulation of several signaling pathways, including Wnt (Kim et al., 1999; Lal et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2007), mTOR (Shillingford et al., 2006), p21/JAK/STAT (Bhunia et al., 2002; Low et al., 2006; Talbot et al., 2011), and activator protein-1 (Arnould et al., 1998; Chauvet et al., 2004; Parnell et al., 2002). Polycystin-2 is a non-selective calcium-permeable cation channel that interacts and forms a complex with PC1 via the coiled-coil domains present in each of these proteins (Qian et al., 1997).

PC1 is subject to several proteolytic cleavages (Chapin and Caplan, 2010; Woodward et al., 2010), including an autocatalytic event that releases the N-terminal extracellular domain, which remains non-covalently associated with the transmembrane domains (Qian et al., 2002). The C-terminal tail of PC1 (PC1-CTT) is cleaved and translocates to the nucleus (Bertuccio et al., 2009; Chauvet et al., 2004; Low et al., 2006; Talbot et al., 2011). Nuclear PC1-CTT regulates cell signaling pathways, including activation of STAT6/P100 and STAT3 (Low et al., 2006; Talbot et al., 2011), and inhibition of β-catenin-mediated canonical Wnt signaling (Lal et al., 2008). ADPKD cyst formation is thought to occur, at least in part, as a result of dysregulation of epithelial cell proliferation and of apoptosis (Chapin and Caplan, 2010; Lanoix et al., 1996; Shibazaki et al., 2008; Starremans et al., 2008; Takiar and Caplan, 2010).

We show that the CTT of PC1 is released by a γ-secretase-dependent cleavage and translocates to the nucleus, where it regulates transcriptional pathways involved in proliferation and apoptosis. Expression of the CTT fragment corrects several of the growth and morphogenesis-related phenotypes that characterize Pkd1-null cells grown in three dimensional (3D) culture. Furthermore, expression of the PC1-CTT rescues the dorsal body curvature that is produced both by inhibition of PC1 expression and by inhibition of γ-secretase activity in zebrafish. Finally, we provide evidence establishing a common mechanism for PC1-CTT inhibition of pro-proliferative and pro-apoptotic signaling pathways through disruption of the relevant transcription factors’ interactions with the transcriptional co-activator p300.

Results

Loss of PC1 in mouse renal epithelial cells causes increased proliferation, apoptosis and cyst development in 3D cell culture

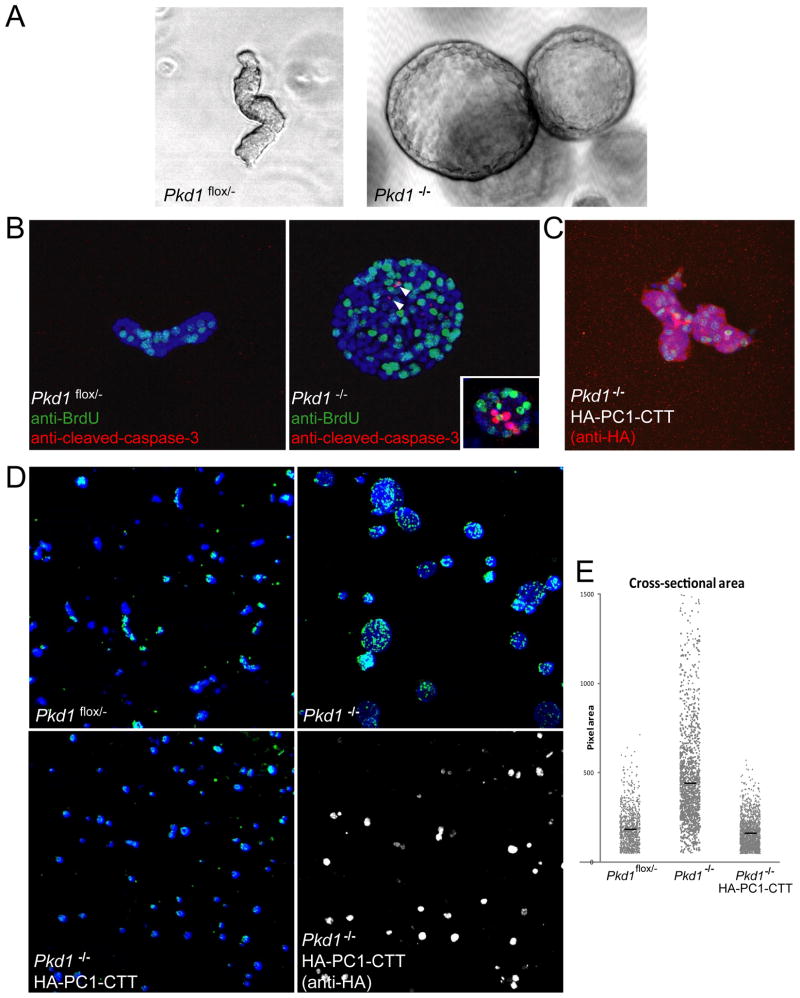

Clonal renal tubular epithelial cell lines derived from Pkd1flox/− mice were transfected with Cre recombinase to generate Pkd1−/− cells (Joly et al., 2006; Shibazaki et al., 2008). These cell lines, which are genetically identical except for the deletion of both copies of the gene encoding PC1 in the Pkd1−/− cells, produced strikingly different multicellular structures when grown in 3D culture. Pkd1flox/− cells grew into extended, tubule-like structures, while the Pkd1−/− cells developed into large, spherical cysts with hollow central lumens (Figure 1A). This can be seen graphically in time-lapse videos of Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells grown in 3D culture (Videos S1–3). The Pkd1−/− cells acquire a hollow central lumen within the first several days of culture, whereas the Pkd1flox/− cells slowly form linear tubule-like structures.

Figure 1.

Pkd1 knockout results in increased proliferation, apoptosis and cystic morphology. (a) Phase contrast imaging of Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells grown in 3-dimensional Matrigel matrix for 10 days. (b) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− structures were incubated with BrdU, fixed and stained with α-BrdU-FITC (green) and α-cleaved Caspase-3 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (c) Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing HA-PC1-CTT were grown in 3-dimensional Matrigel matrix for 10 days, exposed to BrdU, fixed and stained with α-BrdU-FITC (green) and αHA (red) to detect expression of the HA-PC1-CTT. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Cellular structures were imaged on a Leica confocal microscope using a 40x objective. (d) Top two panels: Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells grown in 3-dimensional Matrigel matrix for 7 days and incubated with BrdU were stained with α-BrdU (green) and nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Bottom two panels: Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing HA-PC1-CTT and incubated with BrdU were stained with α-BrdU (green). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue, left panel), and CTT expression was detected with αHA (gray, right panel). (e) Plot of cross-sectional area of cellular structures pictured in (d) (Bars indicate mean area in pixels: Pkd1flox/− = 185, Pkd1−/− = 447, Pkd1−/− HA-PC1-CTT = 163, n = 1000 for each condition).

Pkd1−/− cells displayed higher levels of proliferation as compared to Pkd1flox/− cells, as measured by BrdU incorporation (Figure 1B). Apoptosis, as measured by staining for cleaved Caspase-3, was virtually undetectable in the Pkd1flox/− cells, while apoptosis was evident in the Pkd1−/− cells, both in cyst-lining cells (Figure 1B, arrowheads) and at the center of cell aggregates that had yet to develop a hollow central lumen (Figure 1B, inset).

To determine the effect of the isolated PC1-CTT on cystogenesis, PC1-CTT was conditionally expressed under the control of doxycyclin using a TET-Off inducible expression system in a stably transfected Pkd1−/− cell line. Pkd1−/− cells induced to express PC1-CTT displayed decreased levels of proliferation, as measured by BrdU incorporation. In addition, expression of PC1-CTT in the Pkd1−/− cells resulted in a dramatic change in the morphology of the structures they formed in 3D culture. Instead of large, hollow-lumen, cyst-like structures, the Pkd1−/− cells that express the PC1-CTT developed into branched tubule-like structures lacking a hollow central lumen (Figure 1C). The average sizes of the structures formed by the Pkd1−/− cells that express the PC1 CTT were similar to those measured for the parental Pkd1flox/− cells, and these structures were significantly smaller than the cystic structures formed by the Pkd1−/− cells (Figure 1D and E). Immunostaining performed with an antibody directed against the HA epitope appended to the PC1-CTT construct demonstrates that these small cell clusters and tubule-like structures do indeed express the exogenous PC1-CTT protein (shown in red in Figure 1C and in gray scale in the lower right panel of Figure 1D) and that the PC1-CTT protein is concentrated in the nucleus (Figure S1).

The C-terminal tail cleavage of PC1 is dependent upon γ-secretase

C-terminal cleavage of PC1 was detected in HEK cells transfected with a cDNA construct encoding full-length PC1 tagged at the C-terminus with the DNA-binding domain of Gal4 (Bertuccio et al., 2009). Cleavage of PC1 allows the released CTT-Gal4 to translocate to the nucleus and to stimulate luciferase production from a co-transfected UAS-Luciferase reporter plasmid. Assays are performed in the presence of clasta-lactacystin, to prevent proteasome degradation of the cleaved PC1 CTT (Bertuccio et al., 2009). The γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT was added to the media after transfection and the cells were incubated for 24 hrs (Shearman et al., 2000). PC1 cleavage, as measured by Gal4-driven luciferase expression, was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by DAPT, indicating that PC1-CTT cleavage is dependent upon γ-secretase activity (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

PC1-CTT cleavage is sensitive to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. (a) HEK293 cells transfected with PC1-GalVP, UAS-Luciferase, and Renilla were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT at the indicated concentrations in the presence of clasta-lactacystin for 24 hrs prior to quantification of the luciferase signal. (b) LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing full-length PC1 with a C-terminal 2xHA tag were exposed to DAPT for 24 hrs, in the presence of clasto-lactacystin, before nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation. Proteins were separated on a 10% SDS- polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by immunoblot. Nuclear purification was assessed using α-RNA-Pol II (nuclear fraction) and α-calnexin (non-nuclear fraction). PC1-CTT cleavage fragments were detected using α-HA. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with either siControl (non-targeting RNA) or siRNA directed against human Presenilin-1 or Presenilin-2. qRT-PCR was used to determine knockdown efficiency. PC1-GalVP, UAS-Luciferase, and Renilla were super-transfected into HEK cells after 48 hrs of siRNA treatment to report on PC1-CTT cleavage. Data are mean ± SE of 4 replicates each from 2 independent experiments. (d) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were cultured in 3-dimensional Matrigel matrix for 10 days in media containing either DMSO (vehicle control) or 100uM DAPT, after which they were fixed and imaged on a phase-contrast microscope.

Further evidence for γ-secretase-dependent cleavage of PC1 was obtained through DAPT treatment of LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing a full-length PC1 construct that carries a C-terminal HA tag. Lysates from cells treated with clasta-lactacystin (to prevent proteasome degradation of cleaved PC1 fragments) were fractionated to separate nuclei from cytoplasm, and the resultant fractions were analyzed by immunoblot. Bands corresponding to the cleaved PC1-CTT were detected predominantly in the nuclear fractions and the intensity of this complex of bands was significantly decreased in cells exposed to DAPT (Figure 2B). We used siRNA to knock down expression in HEK293 cells of Presenilin-1 or Presenilin-2, each of which can serve as the catalytic subunit of the functional γ-secretase complex. Loss of Presenilin-1 did not decrease PC1-CTT cleavage as measured by the PC1-GalVP cleavage assay (Figure 2C, left panels). Presenilin-2 knockdown, however, resulted in a significant decrease in PC1-CTT cleavage (Figure 2C, right panels) and a reduction in the nuclear accumulation of PC1 cleavage products (Figure S2).

We next wished to determine whether γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of PC1 is required for the PC1 protein to exert its effects on epithelial morphogenesis. Pkd1flox/− cells cultured in 3D were treated with either DMSO vehicle or with DAPT for 10 days. DAPT treatment resulted in a significant change in morphology in the Pkd1flox/− cells. While DMSO-treated cells formed linear tubule-like structures, DAPT-treated cells formed spherical cyst-like structures with hollow central lumens (Figure 2D, left panels) reminiscent of the structures formed by the Pkd1−/− cells. DAPT treatment had no significant effect on the morphology of Pkd1−/− cells (Figure 2D, right panels).

Expression of PC1-CTT results in reduced proliferation and apoptosis in Pkd1−/− cells

To quantify the effects observed in the 3D cell culture system, Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were cultured in two dimensions on glass coverslips and BrdU incorporation (Figure 3A) and cleaved Caspase-3 staining (Figure S3) were assessed as measures of proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. Pkd1−/− cells displayed a significantly higher level of proliferation than Pkd1flox/− controls. However, reintroduction of the isolated PC1-CTT significantly reduced proliferation of the Pkd1−/− cells to levels similar to those observed in Pkd1flox/− cells (Figure 3B). Similarly, Pkd1−/− cells displayed a significantly higher level of apoptosis when compared to Pkd1flox/− controls. When PC1-CTT expression was induced in Pkd1−/− cells, the level of apoptosis decreased significantly. Expression of PC1-CTT in the Pkd1−/− cells reduced apoptosis to levels similar to those seen in the Pkd1flox/− cells (Figure 3C and Figure S3).

Figure 3.

Effects of PC1-CTT expression on proliferation and apoptosis. (a) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing HA-PC1-CTT encoded by a TET-Off inducible vector were grown on coverslips. PC1-CTT expression was induced in the Pkd1−/− cell line by withdrawal of doxycyclin for 48 hrs prior to BrdU exposure and fixation. Proliferating cells were labeled with α-BrdU-FITC (green), PC1-CTT expression was detected with α-HA (red), and nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (b) Proliferation was quantified using automated cell-counting software. Expression of PC1-CTT in Pkd1−/− cells resulted in a reduction of proliferation to levels approaching those observed in the Pkd1flox/− cells. (c) Apoptosis was assessed by staining with an antibody directed against cleaved Caspase-3 (Figure S3) and quantified using automated cell-counting software. Expression of PC1-CTT in Pkd1−/− cells resulted in a reduction in apoptosis to levels similar to those seen in the Pkd1flox/− cells. Data are mean ± SE of 10 fields each from 3 independent experiments.

PC1-CTT directly interacts with TCF and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling

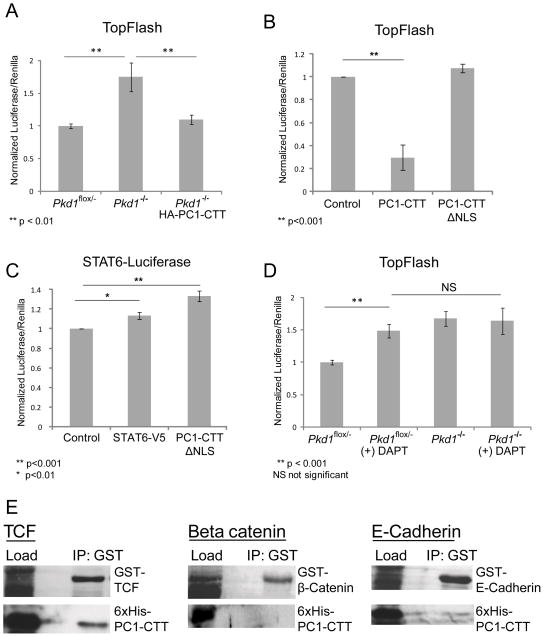

Previous data implicate canonical Wnt signaling as a driver of cyst proliferation. Recent studies show activation of Wnt target genes in cells derived from human ADPKD cystic tissue and demonstrate an interaction between the PC1-CTT and components of the Wnt signaling pathway (Kim et al., 1999; Lal et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2007). The Wnt pathway regulates the size and activity of the cytosolic pool of β-catenin. At the cell membrane, β-catenin is bound by E-cadherin. In resting polarized epithelial cells, β-catenin is predominantly sequestered at the basolateral plasma membrane, where it participates in the formation of E-cadherin-dependent adhesive junctions. Free cytoplasmic β-catenin is recognized by a “destruction complex” that mediates its phosphorylation, targeting it for proteosomal degradation. Activation of Wnt signaling prevents the destruction of free cytosolic β-catenin, which enters the nucleus to serve as a co-activator of the TCF transcription factor and thus induces proliferation (Daugherty and Gottardi, 2007). To measure endogenous Wnt-signaling activity we employed the TopFlash assay, which utilizes a TCF-binding promoter element to drive expression of a luciferase reporter (van de Wetering et al., 1997). Pkd1−/− cells demonstrated significantly higher levels of TCF activity than did the Pkd1flox/− controls. Furthermore, expression of PC1-CTT in the Pkd1−/− cells resulted in a significant reduction in the TopFlash luciferase activity to levels similar to those detected in Pkd1flox/− cells (Figure 4A). This activity is dependent upon the presence of the PC1-CTT nuclear localization sequence (NLS), as evidenced by the fact that a PC1-CTT construct lacking the NLS (PC1-CTT-ΔNLS) (Chauvet et al., 2004) does not exert any inhibitory influence on TopFlash activity ((Lal et al., 2008) and Figure 4B). While the PC1-CTT-ΔNLS construct does not alter TopFlash activity, it is worth noting that this construct is able to produce a significant signal in a reporter assay that measures the activity of the STAT6 pathway (Figure 4C). These data, which are consistent with previous observations indicating that portions of the PC1-CTT can activate STAT6 signaling (Low et al., 2006), demonstrate that loss of the NLS selectively blocks some but not all of the functional activities of the PC1-CTT.

Figure 4.

TopFlash activity is elevated in Pkd1−/− cells and inhibited by PC1-CTT expression. (a) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing HA-PC1-CTT in a TET-Off inducible vector were transfected with TopFlash and Renilla luciferase reporter constructs in the presence or absence of doxycyclin and luciferase activity was measured 24 hrs later. (b) TopFlash activity is significantly inhibited by expression of the PC1-CTT in HEK293 cells. Expression of the PC1-CTTΔNLS does not inhibit TopFlash activity. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct driven by a STAT6-responsive promoter, as a measure of STAT6 activation. Expression of exogenous STAT6, or PC1-CTTΔNLS results in a significant activation of STAT6 promoter-driven luciferase production. (d) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were transfected with TopFlash and Renilla luciferase reporter constructs and exposed to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 24 hrs prior to quantification of luciferase signal. Data are mean ± SE of 4 replicates each from 3 independent experiments. (e) GST-tagged constructs corresponding to the β-catenin-binding domain of TCF, E-Cadherin C-terminal tail and β-catenin were co-expressed with His-tagged PC1-CTT in bacteria. When precipitated with gluathione beads, the PC1-CTT displays a strong direct interaction with TCF, and little direct interaction with E-Cadherin or β-catenin.

Treatment of Pkd1flox/− cells with DAPT abolished the inhibitory effect of PC1 expression on TopFlash activity, consistent with the hypothesis that PC1-CTT cleavage and nuclear translocation of the released CTT fragment are necessary for its inhibitory effect on TCF. DAPT treatment of Pkd1−/− cells did not stimulate any further increase in TopFlash activity, indicating that the increase in Wnt activity obtained through inhibition of γ-secretase is dependent on the presence of PC1 (Figure 4D).

To dissect further the elements of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway that interact directly with PC1-CTT, a bacterial co-expression system was employed to drive simultaneous expression of a His-tagged PC1-CTT and of GST-tagged polypeptides incorporating the sequences of β-catenin, the E-Cadherin cytoplasmic domain, or TCF. When bacterial lysates were subjected to glutathione-sepharose pull-down and the recovered proteins were blotted with anti-His antibody, PC1-CTT exhibited little direct interaction with β-catenin or with E-Cadherin, but showed a strong direct physical interaction with TCF (Figure 4C).

PC1-CTT interacts with CHOP and inhibits its activity

Data suggesting that the PC1-CTT may regulate apoptosis (Figures 1 and 3, and Figure S3) led us to search for novel regulatory targets that could mediate this influence. To identify transcription factors regulated by PC1-CTT, we employed a ‘co-activator trap’ screen, in which over 800 transcription factors are fused to the DNA-binding domain of Gal4 (Amelio et al., 2007). After co-transfection of each transcription factor-Gal4 construct and a Gal4-driven luciferase reporter vector into HEK293 T cells, luciferase assays established baseline activities for each transcription factor. PC1-CTT was then co-transfected and any effect of PC1-CTT on each transcription factor’s activity was measured as a change in luciferase production as compared to its baseline level. Several transcription factors were found to be significantly regulated in the presence of PC1-CTT. One of the most profoundly affected was CHOP-10/GADD153, which induces apoptosis in response to ER stress as part of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004) (Table S1).

To measure the effects of full length PC1 expression on CHOP activation, Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were transfected with the CHOP-Gal4 and the Gal4-luciferase reporter constructs. Pkd1−/− cells displayed significantly higher levels of CHOP activity when compared to the Pkd1flox/− cells. Expression of the soluble PC1-CTT in the Pkd1−/− cells resulted in a significant inhibition of CHOP-Gal4 activity (Figure 5A). In addition, treatment of Pkd1flox/− cells with DAPT abolished the inhibitory effect that PC1 expression exerts on CHOP-Gal4 activity. DAPT treatment of Pkd1−/− cells did not stimulate a further elevation in CHOP activity, indicating that the increase in CHOP activity obtained through inhibition of γ-secretase-dependent protein cleavage is dependent on the presence of PC1 (Figure 5B). Thus, the presence of the PC1 protein acts, via its released CTT, to negatively regulate CHOP activity. Once again, this activity is dependent upon the presence of the PC1-CTT nuclear localization sequence, since the PC1-CTT-ΔNLS construct does not exert any inhibitory influence on CHOP activity (Figure 5C). To determine whether the increased rate of apoptosis observed in the Pkd1−/− cells is indeed a consequence of CHOP activity, Pkd1−/− and Pkd1flox/− cells were subjected to siRNA-mediated knockdown of CHOP expression. Apoptosis was scored by staining for cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 5D). Consistent with the data shown in Figure 3C, the apoptotic rate manifest by the Pkd1−/− cells transfected with a control siRNA was twice that observed for the similarly treated Pkd1flox/− cells. Whereas knockdown of CHOP expression had no effect on the apoptotic rate observed in the Pkd1flox/− cells, treatment with the CHOP siRNA reduced the apoptotic rate in the Pkd1−/− cells to the level measured in the Pkd1flox/− cells. Taken together, these data demonstrate that PC1 reduces CHOP activity in a cleavage-dependent manner, and that elevated CHOP activity accounts for the increased apoptosis that is measured in cells that lack PC1 expression.

Figure 5.

CHOP-Gal4 activity is elevated in Pkd1−/− cells and inhibited by PC1-CTT expression. (a) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing HA-PC1-CTT in a TET-Off inducible vector were transfected with CHOP-Gal4, UAS-Luciferase and Renilla luciferase reporter constructs in the presence or absence of doxycyclin and luciferase activity was measured 24 hrs later. (b) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were transfected with CHOP-Gal4, UAS-Luciferase and Renilla luciferase reporter constructs and exposed to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT for 24 hrs prior to quantification of luciferase signal. Data are mean ± SE of 4 replicates each from 3 independent experiments. (c) CHOP-Gal4 activity is significantly inhibited by expression of the PC1-CTT in HEK293 cells, while it is not inhibited in the presence of the PC1-CTTΔNLS. (d) Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− cells were reverse-transfected with either non-coding siRNA (siControl), or siRNA corresponding to CHOP (siCHOP), and apoptosis levels were measured 48 hrs later by cleaved Caspase-3 staining. (e) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with CHOP-Gal4 and HA-PC1-CTT. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using α-HA sepharose and the immunoprecipitates were then blotted with the indicated antibodies. (f) LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing full-length PC1 with a C-terminal 2xHA tag were transfected with FLAG-CHOP, and subjected to nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation. Endogenously cleaved PC1-CTT was immunoprecipitated from the nuclear fraction using α-HA sepharose and the resulting complexes were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and blotted with the indicated antibodies.

To assess the possibility of a physical interaction between CHOP and the PC1-CTT, HEK cells were transfected with constructs encoding HA-PC1-CTT and a FLAG-tagged CHOP protein. Lysates prepared from these cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA beads. CHOP co-precipitated with the soluble PC1-CTT construct (Figure 5E). This interaction was further validated by immunoprecipitation experiments performed on lysates of nuclear fractions prepared from LLC-PK1 cells stably expressing a full-length PC1 that carries a C-terminal HA tag (Chapin et al., 2010). The endogenously-cleaved PC1-CTT released from the full length PC1 protein co-precipitated with nuclear CHOP (Figure 5F).

PC1-CTT inhibits TCF and CHOP activities by disrupting their interactions with p300

While TCF and CHOP activate discrete transcriptional pathways, they both utilize and depend upon the common transcriptional co-activator, p300/CBP (Li et al., 2007; Ohoka et al., 2007). To determine the potential importance of p300 in the PC1-CTT-mediated regulation of TCF and CHOP, HEK cells were transfected with PC1-CTT alone, or in the presence of over-expressed p300. As shown previously, PC1-CTT expression inhibits TCF activity (as assessed by TopFlash assay) in the context of native levels of p300 protein expression (Lal et al., 2008). Overexpression of p300 eliminated this inhibitory effect of PC1-CTT, suggesting that this inhibitory effect is achieved through competition between the PC1-CTT and p300 for binding to TCF (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

PC1-CTT competitively disrupts the interaction of TCF and CHOP with p300. (a) HEK293 cells were transfected with TopFlash and Renilla luciferase reporter constructs, along with PC1-CTT alone or with PC1-CTT and a construct driving overexpression of full-length p300. (b) HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-p300, and with HA-PC1-CTT where indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with gluathione beads pre-bound with GST-TCF. Recovered complexes were eluted in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, run on a 10% SDS- polyacrylamide gel and blotted with the indicated antibodies. (c, e) Band densitometry was performed using image analysis software to quantitate the data from the co-precipitation experiments shown in panels b and d. Results are expressed as mean ± SE from 4 independent experiments. (d) HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-p300, FLAG-CHOP, and with HA-PC1-CTT where indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with α-FLAG pre-bound to agarose beads to precipitate CHOP, and the recovered complexes were eluted in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, run on a 10% SDS- polyacrylamide gel and blotted with the indicated antibodies.

To test this possibility directly, TCF and CHOP were precipitated from HEK cells transfected with p300 and PC1-CTT (Figure 6B and D). As expected, in the absence of PC1-CTT, TCF and CHOP each co-precipitate with p300 (Hecht and Stemmler, 2003; Ohoka et al., 2007). These interactions were significantly disrupted in cells that express PC1-CTT, suggesting that the C-terminal tail of PC1 exerts its inhibitory effect on the activities of TCF and CHOP by interfering with their interactions with p300 (Figure 6B and C and 6D and E).

PC1-CTT rescues morphant phenotypes in Pkd1-knockdown zebrafish embryos

Morpholino-induced knockdown of the two zebrafish Pkd1 genes, Pkd1a and Pkd1b, produces dorsal body axis curvature, kidney cysts, hydrocephalus, and skeletal abnormalities (Mangos et al., 2010). Of these findings, the dorsal body curvature was considered to be the most reliable marker of Pkd1 knockdown, due to the substantially higher penetrance of this phenotype. Interestingly, treatment of zebrafish embryos with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT produces a similar phenotype, characterized by mild and moderate dorsal axis curvature (Arslanova et al., 2010). To determine the capacity of the PC1-CTT to rescue the phenotype associated with impaired Pkd1 gene expression in vivo, zebrafish embryos were injected with Pkd1a/b morpholinos alone, or with mRNA encoding the PC1-CTT. Knockdown of Pkd1a/b results in dorsal axis curvature, while concurrent injection of the PC1-CTT significantly decreases the severity of the body curvature at 3dpf (Figures 7A and 7B). Injection of mRNA encoding the PC1-CTT-ΔNLS construct did not rescue the body curvature phenotype (Figure S4A and B). A subset of the signaling pathways influenced by the PC1-CTT require the NLS (Wnt and CHOP) while others appear to not require the presence of this motif (e.g. STAT-6) (Figure 4B and C, Figure 5C). Thus, these data suggest that the capacity of the PC1-CTT to ameliorate the severity of the body curvature phenotype involves one or more of the NLS-dependent signaling pathways that are modulated by the PC1-CTT. Finally, injection of mRNA encoding the PC1-CTT, but not mRNA encoding control GFP, partially rescued the body curvature phenotype induced by DAPT treatment, producing a significant increase in the percentage of fish with straight bodies and a decrease in the percentage of moderately curved fish (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Both morpholino knockdown of Pkd1a/b and treatment with DAPT results in dorsal axis curvature in zebrafish embryos, which can be rescued by expression of the PC1-CTT. (a) Morpholinos corresponding to the zebrafish Pkd1a and Pkd1b Polycystin-1 genes were injected into zebrafish embryos at the 1–2 cell stage to impair expression of the two Pkd1 genes. The embryos were subsequently injected with 300nM of mRNA encoding HA-PC1-CTT, where indicated, and imaged at 3dpf. (b) Embryo phenotypes were scored based on the degree of dorsal tail curvature: mild <90 degrees, moderate >90 degrees and severe = tail tip crossing the body axis. The data represent the averages of three separate experiments; error bars represent standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). (c) Embryos were injected with 300nM mRNA encoding either GFP (control) or HA-PC1-CTT at the 1–2 cell stage, then immersed in embryo media containing 25μM DAPT, imaged at 3dpf and scored for the tail curvature phenotype.

Discussion

Our data confirm the role of PC1 as an inhibitor of renal epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis, and provide evidence for the mechanism responsible for this regulation, mediated by cleavage and nuclear translocation of the PC1-CTT. Re-introduction of the PC1 CTT into Pkd1 knockout cells is sufficient to normalize their excessive proliferative and apoptotic activities, and the PC1-CTT is sufficient to rescue the dorsal tail curvature phenotype produced by morpholino-mediated disruption of Pkd1a/b expression in zebrafish. We show that PC1 cleavage is dependent upon γ-secretase activity, and that the released PC1-CTT inhibits TCF and CHOP, thereby regulating proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. Furthermore, injection of mRNA encoding the PC1-CTT is capable of partially rescuing the dorsal tail curvature phenotype produced by exposure of zebrafish embryos to the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT. The similarity of the phenotypes produced by Pkd1a/b disruption and DAPT treatment is intriguing, and the ability of the PC1-CTT to partially rescue both suggests that at least some of the critical biological activities of the PC1 protein are dependent upon its γ-secretase-dependent PC1-CTT cleavage. Finally, we demonstrate that PC1-CTT inhibits TCF and CHOP by disrupting their interaction with the transcriptional co-activator p300, illustrating a common mechanism through which PC1-CTT is capable of regulating two distinct transcriptional pathways.

Hyperproliferation and increased apoptosis are characteristic of ADPKD (Lanoix et al., 1996; Starremans et al., 2008). We found that loss of Pkd1 in otherwise genetically identical cell lines resulted in a significant increase in both proliferation and apoptosis. These experiments were performed in-vitro, thus eliminating any potential effects of the cyst micro-environment on the proliferative or apoptotic potential of the cyst lining cells that might complicate the situation in-vivo. Thus, our data establish that the loss of expression of the Pkd1 gene product is primarily responsible for the proliferative and apoptotic changes seen in ADPKD.

Cleavage of the CTT of PC1 has been observed in several studies (Bertuccio et al., 2009; Chauvet et al., 2004; Lal et al., 2008; Low et al., 2006), and its subsequent translocation to the nucleus strongly implies its role in the regulation of transcriptional pathways. While the cleaved CTT fragment certainly does not recapitulate all of the functions of full-length PC1, our data suggest that the isolated CTT is sufficient to reestablish normal low levels of proliferation and apoptosis, and of TCF and CHOP activity, when expressed in Pkd1 knockout cells. Furthermore, PC1-CTT is capable of at least partially restoring to Pkd1 knockout cells the tubular morphology that is obtained with wild type and Pkd1 heterozygous cells grown in 3D cell culture. Finally, our data suggest that PC1 cleavage by γ-secretase may be necessary for PC1 to mediate its full complement of physiological functions. Inhibiting γ-secretase activity causes PC1-expressing cells that form tubular structures in 3D culture to recapitulate the cystic morphology normally manifest by Pkd1 null cells. It is possible, of course, that γ-secretase influences epithelial morphogenesis in this assay via additional pathways that are independent of PC1. Since Pkd1−/− cells were unaffected by DAPT treatment in both the morphogenesis and the TCF and CHOP assays, however, we conclude that γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of PC1 plays an obligate role in at least a subset of this protein’s physiological functions.

The shedding of the extracellular domain of PC1, together with the cleavage and nuclear translocation of its cytoplasmic domain, mark PC1 as a member of a growing collection of plasma membrane proteins that are cleaved by γ-secretase and participate in direct signaling to the nucleus (Lal and Caplan, 2011). This behavior is exemplified by the Notch (Fortini, 2009), EpCAM (Maetzel et al., 2009), and DCC pathways (Taniguchi et al., 2003). The precise site at which γ-secretase cleaves PC1-CTT has not yet been determined. It is worth noting, however, that γ-secretase appears to exhibit substantial promiscuity in the sequence compositions of its substrate cleavage sites (Beel and Sanders, 2008; Struhl and Adachi, 2000). This promiscuity may account, at least in part, for the number of discrete PC1-CTT cleavage products that are detected in nuclear fractions (Fig. 2B). The precise signals that stimulate γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of PC1 have yet to be discovered.

We report a direct physical interaction between the PC1-CTT and TCF. Lal et al. have suggested that the PC1-CTT inhibits canonical Wnt signaling through an interaction with β-catenin (Lal et al., 2008). Since these experiments assessed the co-immunoprecipitation of epitope tagged proteins co-expressed in human cell lines, the recovered protein complexes may have contained additional members of the signaling pathway, such as TCF, that were not detected in immunoblots that assessed only the presence of the tagged proteins. Thus, it seems likely that the co-precipitation of the PC1-CCT and β-catenin observed by Lal et al. could be attributable to a mutual interaction of both of these proteins with TCF to form an inactive tertiary complex. The bacterial co-expression system utilized in the present study allowed us to further dissect the canonical Wnt pathway and to determine that TCF is a direct binding partner of PC1-CTT. It should be noted that, while activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is sufficient to produce renal cystic disease (Qian et al., 2005; Saadi-Kheddouci et al., 2001), and markers of Wnt signaling appear to be elevated in the context of human ADPKD (Lal et al., 2008), a recent study found that the cyst lining cells of mouse models of ADPKD that express a Wnt/TCF reporter did not manifest elevated levels of Wnt activity (Miller et al., 2011). It is possible, therefore, that activation of Tcf-mediated transcription plays an early, transient role in the initiation of cyst formation that is terminated by the time cysts are manifest. It is also possible that pathways other than those associated with Wnt/TCF drive the hyper-proliferation that is associated with the cystic epithelial cells in ADPKD. In either case, our data demonstrate that cleavage of the PC1 generates a protein that is both anti-proliferative and sufficient to suppress ADPKD-related phenotypes in vitro and in vivo.

The activities of both TCF and CHOP depend upon the common transcriptional co-activator p300 (Li et al., 2007; Ohoka et al., 2007). Our data suggest that PC1-CTT binds directly to the transcription factors TCF and CHOP, and are consistent with the hypothesis that PC1-CTT acts by blocking the p300 binding sites on both TCF and CHOP. The p300 protein, therefore, constitutes a promising convergence point that appears to be utilized by PC1-CTT to regulate two distinct transcription factors. This regulation of TCF and CHOP through interactions with the released PC1-CTT provides a simple and compelling explanation for the dysregulation of proliferation and apoptosis seen in ADPKD.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies, plasmids and cell lines

The following antibodies and labeling reagents were used: α-HA antibody, Rat (Roche), FITC α-BrdU Kit (BD Bioscience), α-Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling), α-RNA Pol II (Santa Cruz), α-calnexin (Stratagene), α-His (Qiagen), α-GST (Amersham), α-FLAG and α-cMyc (Sigma). For laser-scanning fluorescence microscopy, dye-coupled Alexa antibodies (Alexa-488, 594; Molecular Probes) were used as secondary reagents.

The sequence encoding the final 200 amino acids of human Polycystin-1 (4102–4302), containing a 2x HA tag at the N-terminus, was cloned into the pNRTis-21 vector (Tenev et al., 2000). The sequence for human PC1-CTT (residues 4102–4302 of Pkd1) was modified by deleting residues 4134–4154, corresponding to the putative nuclear localization sequence (NLS) to generate the PC1-CTTΔNLS (Chauvet et al., 2004). Stable cell lines were generated by transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and selection with 350μg ml−1 zeocin (Invitrogen). Expression was inhibited with 100ng ml−1 doxycyclin. Full-length human PC1 was cloned into pcDNA3.1.neo (Invitrogen) with 2x HA tag or Gal4VP16 appended to the C-terminus as described (Bertuccio et al., 2009). Stable cell clones were selected with 2mg ml−1 geneticin (Gibco). GL4.31[luc2P/GAL4UAS](Promega) was used as a Gal4 promoter-driven firefly luciferase reporter construct. The TopFlash plasmid was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. pRL-TK, a vector constitutively expressing Renilla luciferase, was included as an internal control to normalize for transfection differences. The sequence encoding the PC1-CTT was cloned into the pETDuet vector with an N-terminal 6xHis tag, along with either the GST-E-Cadherin cytoplasmic domain, GST-β-catenin, or GST-TCF β-catenin binding region (Gottardi and Gumbiner, 2004). The CHOP-Gal4 construct was provided by Dr. John Hogenesch (Department of Pharmacology, U. of Pennsylvania). The sequence encoding full-length CHOP was cloned into the pCMV-3Tag-1A vector (Stratagene) to generate 3xFLAG-CHOP. The sequence encoding human p300 (FL or AA 1–664) was cloned into the pCMV-Tag 3B vector (Stratagene) to generate Myc-p300.

HEK 293T cells (Chauvet et al., 2004), LLC-PK1 cells, and Pkd1flox/− and Pkd1−/− TSLargeT renal proximal tubule cells (Joly et al., 2006; Shibazaki et al., 2008) were maintained as described.

3D cell culture, α-BrdU staining and cell counting

Pkd1flox/−, Pkd1−/− and Pkd1−/− stably expressing pNRTis HA-PC1-CTT were trypsinized and mixed with 300uL liquid Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and allowed to solidify for 30 min at 37°C, after which media was added with or without 100ng ml−1 doxycyclin and the cells were grown for 7–10 days. These cell lines were grown on coverslips in parallel for quantification of proliferation and apoptosis.

BrdU was added to the media for 90min prior to fixation. Cells grown on coverslips were stained as per BD protocol. Cells grown in Matrigel were fixed for 1.5 hours at 37°C, permeabilized for 30 min at 4°C, re-fixed for 15 min at RT, treated with DNase for 3 hrs at 37°C, incubated with the α-BrdU 1°Ab (1:100) for 5 days at 4°C, followed by three 2-hour washes and by incubation for 1 day with 2°Ab (1:200); nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes).

Cells grown on coverslips were imaged using an Olympus BX51 epifluorescent microscope equipped with a 20x objective. The percentages of BrdU or Caspase-3 positive cells were quantified using a threshold method in conjunction with the ImageJ software package plugin ‘Nucleus Counter.’

The cross-sectional areas of the cell structures grown in 3-dimensional Matrigel culture were calculated using ImageJ software. Cells were stained with α-BrdU, α-HA and Hoechst 33342 and imaged using an Olympus BX51 epifluorescent microscope equipped with a 10x objective. Cell structures were thresholded from background, and the cross-sectional area of each cell cluster was calculated using the ImageJ ‘analyze particles’ plugin, with a minimum size cutoff of 50 pixels to filter out isolated cells and debris.

Cell fractionation

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions was performed as previously described (Chauvet et al., 2004). Cells grown in 10-cm dishes in the presence of 25 μM clasta-lactacystin were harvested in cold PBS, centrifuged for 5 min at 500g, and resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10mM KCl, and protease inhibitors). Cells were homogenized in a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer, chilled on ice for 10 min, and then rotated for 15 min. Nonidet P-40 was added to a final concentration of 1% and the preparations were rotated for an additional 15 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 1500g for 5 min. The resulting supernatant formed the non-nuclear fractions. The pellets (nuclear fractions) were washed in hypotonic buffer for 10 min, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 200mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors), and rotated for 10 min. Pelleted nuclei were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer and prepared for immunoblot anaylsis. The protein concentration of each sample was determined using a Bio-Rad colorimetric protein concentration assay.

Co-activator trap screen

The co-activator trap screen was performed as previously described (Amelio et al., 2007). A pcDNA3.1 construct expressing HA-PC1-CTT was co-transfected with each of 837 transcription factor-Gal4 fusion proteins and the GAL4 luciferase and Renilla reporter plasmids into HEK293Tcells in a 384-well plate. Cells were cultured for 24 h in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2. BrightGlo (Promega) reagent (35 μl) was added to each well, and luciferase luminescence was measured with an Acquest plate reader (LJL Biosystems).

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assay

Pkd1flox/− cells, Pkd1−/− cells and Pkd1−/− cells stably expressing pNRTis HA-PC1-CTT were plated in 24-well tissue-culture plates and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at 80–100% confluency. Luciferase reporter constructs: (TopFlash or GL4.31[luc2P/GAL4UAS] (0.2ug) and CHOP-Gal4 (0.05ug), and pRL-TK (Renilla) were mixed with 2uL Lipofectamine. HEK293 cells were transfected with STAT6-Luciferase (kind gift of Dr. S. J. Hacque, Cleveland Clinic Foundation) (Haque et al., 1997) or TOPFlash-luciferase, or CHOP-Gal4/Gal4-luciferase (0.2ug), and either control plasmid, STAT6-V5, HA-PC1-CTT or HA-PC1-CTTΔNLS, and pRL-TK (Renilla). Transfection mixtures were added drop wise to cell culture media (containing 80uM DAPT (Sigma) when indicated) and incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. The amount of DNA in each well was equalized through the addition of a control plasmid, pcDNA3.1, which was also used for mock transfection. Transfected cells were harvested with PBS and lysed with 100 mL of passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase levels were assayed using the Dual Luciferase Assay Reagent kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase signals were determined in a GloMaxTM 20/20 luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI).

siRNA treatment

HEK293 cells were transfected with 100 nM target-specific siRNA or control siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000. Control siRNA: Silencer Negative Control siRNA#1 (#AM4611, Ambion). PSEN1: validated siRNA (SI02662688, Qiagen). PSEN2: validated sRNA (AM51331, Ambion). Knockdown of CHOP was accomplished according a published protocol (Ishikawa et al., 2009).

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblot and GST pulldown

Cells were lysed by sonication in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA with protease inhibitors (Roche). Precleared lysates (18,000g, 30 min) were incubated at 4°C overnight with either monoclonal-anti-HA agarose, anti-FLAG-M2 agarose (Sigma), or glutathione-sepharose 4B beads (Amersham) prebound with indicated GST fusion protein constructs harvested from BL21 bacteria by standard procedures (Stratagene). Beads were collected by centrifugation and the pellets were washed in lysis buffer 3 times for 10 min with rotation at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were eluted in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (25mM TrisHCL pH 6.7, 10% glycerol, 1% SDS, 50mM DTT, bromophenol blue).

Proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and then electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), incubated in blocking buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 5% (w/v) powdered milk, 0.1% Tween) for 60 min, and then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight: monoclonal α-HA (Rat) antibody (1:5000, Roche), polyclonal α-FLAG (1:5000, Sigma), polyclonal α-cMyc (1:5000, Sigma), polyclonal α-GST (Goat) (1:10,000 Amersham), α-His (1:5000, Qiagen). Subsequently, primary antibody binding was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rat, anti-rabbit or anti-goat secondary antibodies (1:5,000-10:000; Jackson Labs), and proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (ECL, Amersham Biosciences).

Zebrafish morpholino antisense oligonucleotide and mRNA injections and drug treatment

Morpholino-induced knockdown of Pkd1a and Pkd1b expression was performed as previously reported (Mangos et al., 2010). Wild-type embryos at the 1- to 2-cell stage were microinjected with 4.6 nl of a 0.15mM antisense morpholino oligonucleotide solution (Gene Tools LLC) with 0.1% Phenol Red using a nanoject2000 microinjector (World Precision Instruments). The sequences of the morpholinos targeting Pkd1a and Pkd1b were identical to those that have been previously described (Mangos et al., 2010); briefly, the splice donor-blocking oligonucleotide sequences were Pkd1a MO ex8: 5′-GATCTGAGGACTCACTGTGTGATTT-3′; Pkd1b MO ex45: 5′-ACATGATATTTGTACCTCTTTGGTT-3′. Gene Tools standard negative control morpholino was used as an injection control and demonstrated no effect on development. Drug treatment: after mRNA injection at the 1–2 cell stage, embryos were placed in a 10cm dish with 30mL embryo media containing 25μM DAPT dissolved in DMSO and imaged 3dpf as described (Arslanova et al., 2010).

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± S.E. Differences between means were evaluated using Student’s t test or analysis of variance as appropriate. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vanathy Rajendran for the generation of PC1 stable cell lines, Arthit Chairoungdua for assistance with live cell imaging, Lu Zhou for expertise and assistance with zebrafish embryo microinjection, and members of the Caplan lab for discussion and advice. We thank Drs. Saikh Jaharul Haque for the gift of the STAT6 reporter reagents and Lloyd Cantley for insightful suggestions. This work was supported by NIDDK grants 1F30DK083227-01A1 (DMM), DK57328 and DK090744 (MJC, ZS, SS) and by CDMRP PR093488 (MJC) from the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

D.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; H.C. generated PC1-HA stable cell lines; J.B. and J.H. performed ‘co-activator trap’ screen; Z.Y. and S.S. generated Pkd1 knockout cell lines; Z.S. supervised the zebrafish embryo injection experiments; M.J.C. planned the project, designed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amelio A, Miraglia L, Conkright J, Mercer B, Batalov S, Cavett V, Orth A, Busby J, Hogenesch J, Conkright M. A coactivator trap identifies NONO (p54nrb) as a component of the cAMP-signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20314–20319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707999105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnould T, Kim E, Tsiokas L, Jochimsen F, Grüning W, Chang J, Walz G. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene product mediates protein kinase C alpha-dependent and c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent activation of the transcription factor AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6013–6018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslanova D, Yang T, Xu X, Wong ST, Augelli-Szafran CE, Xia W. Phenotypic analysis of images of zebrafish treated with Alzheimer’s gamma-secretase inhibitors. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beel A, Sanders C. Substrate specificity of gamma-secretase and other intramembrane proteases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1311–1334. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7462-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccio C, Chapin H, Cai Y, Mistry K, Chauvet V, Somlo S, Caplan M. Polycystin-1 C-terminal cleavage is modulated by polycystin-2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21011–21026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhunia A, Piontek K, Boletta A, Liu L, Qian F, Xu P, Germino F, Germino G. PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell. 2002;109:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin HC, Caplan MJ. The cell biology of polycystic kidney disease. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:701–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin HC, Rajendran V, Caplan MJ. Polycystin-1 surface localization is stimulated by polycystin-2 and cleavage at the G protein-coupled receptor proteolytic site. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:4338–4348. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet V, Tian X, Husson H, Grimm D, Wang T, Hiesberger T, Hieseberger T, Igarashi P, Bennett A, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, et al. Mechanical stimuli induce cleavage and nuclear translocation of the polycystin-1 C terminus. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1433–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI21753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty RL, Gottardi CJ. Phospho-regulation of Beta-catenin adhesion and signaling functions. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:303–309. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00020.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini M. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi C, Gumbiner B. Distinct molecular forms of beta-catenin are targeted to adhesive or transcriptional complexes. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:339–349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque SJ, Wu Q, Kammer W, Friedrich K, Smith JM, Kerr IM, Stark GR, Williams BR. Receptor-associated constitutive protein tyrosine phosphatase activity controls the kinase function of JAK1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8563–8568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Torres V. Polycystic kidney disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:321–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.101707.125712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht A, Stemmler M. Identification of a promoter-specific transcriptional activation domain at the C terminus of the Wnt effector protein T-cell factor 4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3776–3785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Ward C, Peral B, Aspinwall R, Clark K, San Millán J, Gamble V, Harris P. The polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple cell recognition domains. Nat Genet. 1995;10:151–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa F, Akimoto T, Yamamoto H, Araki Y, Yoshie T, Mori K, Hayashi H, Nose K, Shibanuma M. Gene expression profiling identifies a role for CHOP during inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. J Biochem. 2009;146:123–132. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joly D, Ishibe S, Nickel C, Yu Z, Somlo S, Cantley L. The polycystin 1-C-terminal fragment stimulates ERK-dependent spreading of renal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26329–26339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Arnould T, Sellin L, Benzing T, Fan M, Grüning W, Sokol S, Drummond I, Walz G. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene product modulates Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4947–4953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal M, Caplan M. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis: signaling pathways and biological functions. Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26:34–44. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00028.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal M, Song X, Pluznick J, Di Giovanni V, Merrick D, Rosenblum N, Chauvet V, Gottardi C, Pei Y, Caplan M. Polycystin-1 C-terminal tail associates with beta-catenin and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3105–3117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanoix J, D’Agati V, Szabolcs M, Trudel M. Dysregulation of cellular proliferation and apoptosis mediates human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) Oncogene. 1996;13:1153–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sutter C, Parker D, Blauwkamp T, Fang M, Cadigan K. CBP/p300 are bimodal regulators of Wnt signaling. EMBO J. 2007;26:2284–2294. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low S, Vasanth S, Larson C, Mukherjee S, Sharma N, Kinter M, Kane M, Obara T, Weimbs T. Polycystin-1, STAT6, and P100 function in a pathway that transduces ciliary mechanosensation and is activated in polycystic kidney disease. Dev Cell. 2006;10:57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maetzel D, Denzel S, Mack B, Canis M, Went P, Benk M, Kieu C, Papior P, Baeuerle P, Munz M, Gires O. Nuclear signalling by tumour-associated antigen EpCAM. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:162–171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangos S, Lam PY, Zhao A, Liu Y, Mudumana S, Vasilyev A, Liu A, Drummond IA. The ADPKD genes pkd1a/b and pkd2 regulate extracellular matrix formation. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:354–365. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MM, Iglesias DM, Zhang Z, Corsini R, Chu L, Murawski I, Gupta I, Somlo S, Germino GG, Goodyer PR. T-cell factor/beta-catenin activity is suppressed in two different models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80:146–153. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N, Hattori T, Kitagawa M, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. Critical and functional regulation of CHOP (C/EBP homologous protein) through the N-terminal portion. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35687–35694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell S, Magenheimer B, Maser R, Zien C, Frischauf A, Calvet J. Polycystin-1 activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and AP-1 is mediated by heterotrimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19566–19572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian CN, Knol J, Igarashi P, Lin F, Zylstra U, Teh BT, Williams BO. Cystic renal neoplasia following conditional inactivation of apc in mouse renal tubular epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3938–3945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Boletta A, Bhunia A, Xu H, Liu L, Ahrabi A, Watnick T, Zhou F, Germino G. Cleavage of polycystin-1 requires the receptor for egg jelly domain and is disrupted by human autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease 1-associated mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16981–16986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252484899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Germino F, Cai Y, Zhang X, Somlo S, Germino G. PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nat Genet. 1997;16:179–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti S, Consugar M, Chapman A, Torres V, Guay-Woodford L, Grantham J, Bennett W, Meyers C, Walker D, Bae K, et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2143–2160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi-Kheddouci S, Berrebi D, Romagnolo B, Cluzeaud F, Peuchmaur M, Kahn A, Vandewalle A, Perret C. Early development of polycystic kidney disease in transgenic mice expressing an activated mutant of the beta-catenin gene. Oncogene. 2001;20:5972–5981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman MS, Beher D, Clarke EE, Lewis HD, Harrison T, Hunt P, Nadin A, Smith AL, Stevenson G, Castro JL. L-685,458, an aspartyl protease transition state mimic, is a potent inhibitor of amyloid beta-protein precursor gamma-secretase activity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8698–8704. doi: 10.1021/bi0005456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibazaki S, Yu Z, Nishio S, Tian X, Thomson R, Mitobe M, Louvi A, Velazquez H, Ishibe S, Cantley L, et al. Cyst formation and activation of the extracellular regulated kinase pathway after kidney specific inactivation of Pkd1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1505–1516. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford J, Murcia N, Larson C, Low S, Hedgepeth R, Brown N, Flask C, Novick A, Goldfarb D, Kramer-Zucker A, et al. The mTOR pathway is regulated by polycystin-1, and its inhibition reverses renal cystogenesis in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5466–5471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509694103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starremans P, Li X, Finnerty P, Guo L, Takakura A, Neilson E, Zhou J. A mouse model for polycystic kidney disease through a somatic in-frame deletion in the 5′ end of Pkd1. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1394–1405. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G, Adachi A. Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of notch and other transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell. 2000;6:625–636. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiar V, Caplan MJ. Polycystic kidney disease: Pathogenesis and potential therapies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot JJ, Shillingford JM, Vasanth S, Doerr N, Mukherjee S, Kinter MT, Watnick T, Weimbs T. Polycystin-1 regulates STAT activity by a dual mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7985–7990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103816108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Kim S, Sisodia S. Presenilin-dependent “gamma-secretase” processing of deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30425–30428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Böhmer S, Kaufmann R, Frese S, Bittorf T, Beckers T, Böhmer F. Perinuclear localization of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 and inhibition of epidermal growth factor-stimulated STAT1/3 activation in A431 cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:261–271. doi: 10.1078/S0171-9335(04)70029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, et al. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P. Polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:151–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward OM, Li Y, Yu S, Greenwell P, Wodarczyk C, Boletta A, Guggino WB, Qian F. Identification of a polycystin-1 cleavage product, P100, that regulates store operated Ca entry through interactions with STIM1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Ye C, Zhou Q, Zheng R, Lv X, Chen Y, Hu Z, Guo H, Zhang Z, Wang Y, et al. PKD1 inhibits cancer cells migration and invasion via Wnt signaling pathway in vitro. Cell Biochem Funct. 2007;25:767–774. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.