Abstract

Signaling and internalization of Ste2p, a model G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, are reported to be regulated by phosphorylation status of serine (S) and threonine (T) residues located in the cytoplasmic C-terminus. Although the functional roles of S/T residues located in certain C-terminus regions are relatively well characterized, systemic analyses have not been conducted for all the S/T residues that are spread throughout the C-terminus. A point mutation to alanine was introduced into the S/T residues located within three intracellular loops and the C-terminus individually or in combination. A series of functional assays such as internalization, FUS1-lacZ induction, and growth arrest were conducted in comparison between WT- and mutant Ste2p. The Ste2p in which all S/T residues in the C-terminus were mutated to alanine was more sensitive to α-factor, suggesting that phosphorylation in the C-terminus exerts negative regulatory activities on the Ste2p signaling. C-terminal S/T residues proximal to the seventh transmembrane domain were important for ligand-induced G protein coupling but not for receptor internalization. Sites on the central region of the C-terminus regulated both constitutive and ligand-induced internalization. Residues on the distal part were important for constitutive desensitization and modulated the G protein signaling mediated through the proximal part of the C-terminus. This study demonstrated that the C-terminus contains multiple functional domains with differential and interdependent roles in regulating Ste2p function in which the S/T residues located in each domain play critical roles.

Keywords: Ste2p, C-terminus, Phosphorylation, Internalization, FUS-lacZ, Growth arrest

1. Introduction

Activation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) accompanies an adaptive response that involves the arrest of G protein signaling and receptor internalization. In mammalian GPCRs, this adaptive process involves the coordinated actions of two families of proteins: the G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) and the arrestins (1–3). Ste2p, the tridecapeptide α-factor pheromone receptor of S. cerevisiae, also undergoes a robust internalization in response to pheromone binding. As in mammalian GPCRs, a main cellular event that plays a key role in the internalization of Ste2p is the phosphorylation of the S/T residues, which is presumably mediated by yeast casein kinase I homologues, Yck1p and Yck2p (4, 5).

The role of the C-terminus in the functional regulation of Ste2p was determined to be negative feedback, since the cells expressing receptors with truncated C-terminus are more sensitive to α-factor (6, 7), and the receptors are resistant to internalization (6). Subsequent studies were conducted that focused on the specific roles of S/T residues, which are the potential phosphorylation sites of casein kinase. For example, mutation of serine residues in the S331INNDAKSS339 sequence in the C-terminus successfully inhibited the constitutive internalization but not the ligand-induced internalization of Ste2p (4, 8). Later it was found that mutation of three additional serine residues located in the CT3 and CT4 (Fig. 1; S342, S356, S360) could inhibit the internalization of Ste2p to a moderate extent (9), suggesting that more S/T residues located within the intracellular loops or C-terminus could be involved in the ligand-induced internalization of Ste2p.

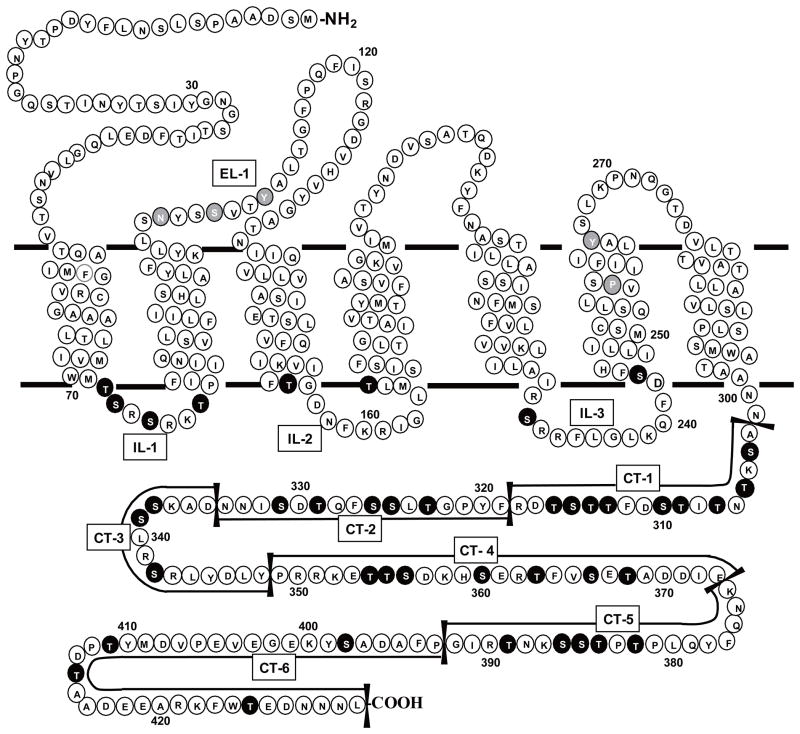

Fig. 1. Snake Diagram of Ste2p.

EL indicates extracellular loop, IL indicates intracellular loop, and CT refers to the C-terminus. The CT was divided into six regions based on the distribution of serine and threonine residues (black circles with white letters)as shown in the diagram. Ser and Thr in the CT and the other intracellular regions were mutated to alanine and residues in other domains (gray circles with white letters) were mutated as follows: N105C, S108C, Y111C, P258L, and Y266A.

In this study, we mutated all of the S/T residues located within the intracellular regions of Ste2p, which include three intracellular loops and C-terminus. In case of the C-terminus, it was divided into six different regions depending on the distribution of S/T residues (CT-1 through CT-6, Fig. 1), and the S/T residues located within each region were mutated separately or in combination with other regions. Functional assays were conducted for those mutants to determine which S/T residues located in the specific region play critical regulatory role(s) in receptor functions. The experiments reported herein are the first to examine the effect of mutating all potential phosphorylation sites in the intracellular loops and C-terminus of the full length Ste2p.

Serine and threonine residues in the intracellular loops (IL1-IL3) were involved in signaling but not internalization. The proximal CT region (CT-12) was important for ligand-induced G protein coupling but not receptor internalization, the central CT region (CT-345) regulated both constitutive and ligand-induced Ste2p internalization, and the distal CT region (CT-6) was important for maintaining a low level of basal signaling activity. In addition, regulatory interactions between distal (CT-6) and proximal portions (CT-12) of the C-terminus were observed. Overall, our study demonstrated that the C-terminus is divided into multiple functional domains in which potential phosphorylation sites mediate differential and interdependent roles in regulating Ste2p functions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Saccharomyces cerevisiae LM102 cells (10) were used to measure α-factor-induced growth arrest (halo assay), gene expression (FUS1-lacZ assay), and receptor internalization. LM102 carried the bar1 mutant allele, which inactivated the BAR1 protease that is responsible for degrading α-factor, and a FUS1-lacZ gene, which served as a pheromone-inducible reporter. The genotype for the LM102 strain is as follows: MATa, bar1, his4, leu2, trp1, met1, ura3, FUS1-lacZ::URA3, ste2-dl (the region encoding the α-factor receptor was deleted). Cells were routinely grown and maintained at 30°C on solid complex medium lacking tryptophan (MLT medium) (11). For growth of liquid cultures, cells were incubated at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) in MLT broth.

2.2. Plasmid constructs

The WT STE2 gene containing a native promoter was cloned into the yeast/bacterial shuttle vector, pGA314.WT (12). For site-directed mutagenesis of STE2 (refer to Fig. 1), single-stranded phagemid DNA was prepared from pGA314.WT by infecting Escherichia coli CJ236 (dut− ung−) harboring pGA314.WT with the helper phage M13K07. Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis of the single-stranded phagemid DNA was conducted as described previously (13). For the construction of a C-terminally GFP-tagged Ste2p by in vivo ligation in yeast, a Stu I site (AGGCCT) was artificially created immediately after the stop codon in WT STE2 gene in the pGA314.WT vector. This plasmid was linearized by digestion with Stu I and introduced into the ste2Δ LM102 strain together with the PCR product of the GFP gene that had been amplified from a template described previously (14) using the two primers containing the overlapping regions for the C-terminal sequence of Ste2p. Ste2-GFP-forward: 5′TGGACTGAAGATAATAATAATTTATTATCAAAATTTACGatggtgagcaagggcgag3 and Ste2-GFP-backward: 5′AGTAACCTTATACCGAAGGTCACGAAATTACTTTTTCAAAGCtcagtacagctcgtccat gcc3′ (the upper case letters represent the sequence of Ste2p, and the lower case letters represent the sequence of GFP). The in vivo ligation products were selected on media lacking tryptophan. For microscopy studies using fluorescent pheromone (15), the open reading frame of WT and the CT-345 mutant STE2 was amplified by PCR and cloned by homologous recombination into plasmid p424GPD, a 2 μ based shuttle vector with a GPD promoter, CYC1 terminator, and TRP marker for selection in yeast (16). All of the newly prepared plasmids verified by DNA sequencing, and their proper expressions were confirmed by radioligand binding at 10 nM [3H]-α-factor.

2.3. Growth arrest (halo) assay

Halo assays were carried out as described elsewhere (17). Briefly, a yeast nitrogen base (YNB) without amino acids (Difco) with 2% glucose and 2% agar (SD medium), supplemented with histidine (20 μg/ml), leucine (30 μg/ml), and methionine (20 μg/ml), was overlaid with 4 ml of the cell suspension (2.5×105 cells/ml, 1.1% Nobel agar). Filter discs (sterile blanks from Difco), 6 mm in diameter, were impregnated with 10-μl portions of the α-factor solutions at various concentrations and placed onto the overlay. The αfactor used in this study was [Nle12]α-factor (18), which is isosteric, equally active, and has the same binding affinity as the WT (WT) pheromone (12). The plates were incubated at 30°C for 24–36 hr and examined for the presence of clear zones (halos) around the discs. The data is expressed as the diameter of the halo, including the diameter of the disc, from three independent replicates.

2.4. Microscopy Methods

Cells expressing GFP-tagged WT or CT-345 C-terminus mutant Ste2p were grown overnight in MLT broth, subcultured into fresh MLT, and grown for two doubling times. Pheromone (10 nM) was added to the culture medium, and cells were observed after 15 minutes incubation at 30°C. Images were acquired with an Olympus MagnaFire digital camera with PictureFrame software (Optronics, Goleta, CA, USA).

2.5. FUS1-lacZ gene induction assay

LacZ gene induction was determined with a fluorescein-containing galactopyranoside analog (19) using LM102 cells that contained a FUS1-lacZ gene inducible by the mating pheromone. Cells were grown overnight in MLT medium broth at 30°C. Following a 50-fold dilution into fresh MLT, those cells were grown for an additional 4 to 5 hours to a density of 1.0×107 cells/ml. Ninety microliters of the cell suspension were added to microtiter plate wells containing 10 μl α-factor at various amounts so that the final α-factor concentration ranged from 10−11 to 10−6 M. Following an incubation for 90 min at 30°C with gentle shaking, 20 μl of FDG solution (0.25 mM fluorescein di-β-D-galactopyranoside in 2.5% Triton X-100) was added to each well and incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C. Fluorescence was measured using a multi-well plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm.. The FUS1-lacZ induction was measured in triplicate, normalized to the WT level, and expressed as a percentage of the control. Data were plotted and analyzed to determine the EC50 values (the concentration of pheromone required to elicit one-half the maximal response) using Prism (GraphPad,Software, La Jolla, CA.).

2.6. Agonist-induced internalization of Ste2p

The internalization of Ste2p was measured as previously reported (4) with minor modifications. Briefly, the cells were cultured overnight to a density of 0.2 – 2×107 cells/ml, harvested by centrifugation, washed, and re-suspended in ice-cold YPAD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose with 40 mg/L adenine) at a concentration of 5×108 cells/ml and kept on ice until needed. [3H]-α-factor (18) at a final concentration of 10 nM (20 Ci/mmol) was added to 250 μl ice-cold cell suspension and then incubated for 45 min with occasional stirring. Cells were washed at 4°C by centrifugation with YPAD to remove unbound [3H]-α-factor and incubated in YPAD medium at 30°C. At various times two aliquots were removed. One aliquot was washed at 4°C by centrifugation with pH 1.0 buffer (50 mM sodium citrate) to measure internalized Ste2p, and the second aliquot was washed at 4°C by centrifugation with pH 6.0 buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate) to measure the total (surface bound plus internalized) Ste2p. The radioactivity was measured using a Packard 1900TR liquid scintillation counter. Nonspecific binding, defined as the radioactivity associated with ste2Δ LM102 cells under the same experimental conditions, was subtracted from the total counts. The internalization of receptor proteins was calculated as (binding at pH 1.0 – non-specific binding)/(binding at pH 6.0 – non-specific binding) using triplicate determinations.

2.7. Constitutive internalization of Ste2p

A slight modification of the method reported by Hicke et al. (4) was used to measure the constitutive internalization of Ste2p. Briefly, cells were prepared as described above for the agonist-induced internalization assay, resuspended to a density of 5×108 cells/ml in YPUAD (YPAD containing 40 mg/L uracil), and incubated at 30°C for 5 min. Cycloheximide (20 μM) was added to cells in order to inhibit the de novo synthesis of Ste2p, and cells were incubated at 30°C in the absence of α-factor for one hour and placed on ice to stop constitutive receptor internalization. [3H]-α-factor at a final concentration of 20 nM was then added to 250 μl of the cell suspension in YPUAD and incubated on ice for 45 min with occasional mixing to measure the remaining Ste2p on the cell surface. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 4 μM non-radioactive α-factor. The cells were washed with pH 6.0 buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate), and the amount of pheromone associated with the cells was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The constitutive internalization of receptor proteins was calculated as the specific binding to cells incubated on ice after adding cycloheximide minus the specific binding to cells incubated at 30°C after adding cycloheximide divided by the specific binding to cells incubated on ice after adding cycloheximide. Assays were conducted in duplicate and repeated 2–3 times.

2.8. Statistics

All of the results are expressed as the mean±SEM. Comparisons between groups were performed using ANOVA test. For some results, Student’s t test was also used.

3. Results

3.1. Potential phosphorylation sites on the intracellular loops are not required for ligand-induced internalization but influence signal transduction

The first intracellular loop of Ste2p contains four possible phosphorylation sites for serine/threonine (S/T) kinases, while the second and third intracellular loops each contain two potential sites (Fig. 1). In order to determine which, if any, of those potential phosphorylation sites are involved in the signaling through G protein or internalization, all were mutated to alanine as individual regions or in combination with other regions, as indicated in Table I. Based on the results of binding assays with 3H-α-factor, the expression level of those intracellular loop mutants was not significantly altered (data not shown).

Table 1.

Notation and descriptions for intracellular Ste2p mutantsa.

| Receptor | Regions with Ala replacement of Ser and Thr |

|---|---|

| IL-12 | IL-1 and IL-2 |

| IL-23 | IL-2 and IL-3 |

| CT-12 | CT-1 and CT-2 |

| CT-123 | CT-1, CT-2, and CT-3 |

| CT-1234 | CT-1, CT-2, CT-3, and CT-4 |

| CT-12345 | CT-1, CT-2, CT-3, CT-4, and CT-5 |

| CT-126 | CT-1, CT-2, and CT-6 |

| CT-123456 | CT-1, CT-2, CT-3, CT-4, CT-5, and CT-6 |

| CT-345 | CT-3, CT-4, and CT-5 |

| CT-45 | CT-4 and CT-5 |

| CT-6 | CT-6 |

IL-1, IL-2 and IL-3 refer to the 1st, 2nd & 3rd intracellular loops, respectively. CT-1, CT-2, CT-3, CT-4, CT-5, and CT-6 refer to the C-terminal domains shown in Fig. 1.

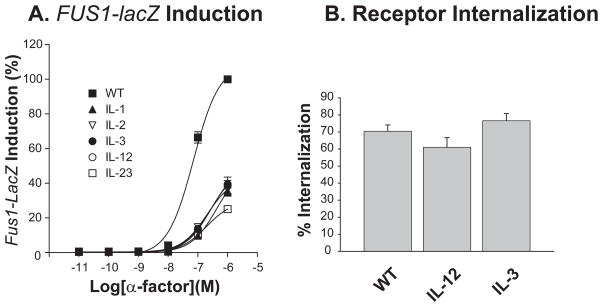

As determined by the FUS1-lacZ reporter gene induction assay, maximal signaling of each intracellular loop mutant receptor (IL-1, IL-2, IL-3) or in combination (IL-12, IL-23) significantly decreased (p<0.001) to approximately 30% of the wild type (WT) at 1 μM α-factor, and the EC50 value increased about three times (from 71 nM to over 200 nM). Gene induction by those same receptors was approximately 10-fold lower at 0.1 μM α-factor (Fig. 2A). In contrast, simultaneous mutations of S/T residues in the 1st and 2nd loops (IL-12) and mutations in the 3rd intracellular loop (IL-3) alone only slightly altered agonist-induced internalization of Ste2p (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Effects of mutations of Ser/Thr residues within the intracellular loop on the FUS1-lacZ reporter gene induction and α-factor-induced internalization of Ste2p.

(A) The final α-factor concentration ranged from 10−11 to 10−6 M. The first, second, and third intracellular loop mutants are designated by IL-1, IL-2 and IL-3, respectively. In IL-12, the first and second intracellular loops are mutated, and in IL-23, the second and third intracellular loops are mutated. All of the mutants tested showed significantly low FUS1-lacZ induction at 10−6 and 10−7 M of α-factor (p<0.001) compared to WT Ste2p. The error bars are small enough to be contained within the symbols on the figure.

(B) Effects of the intracellular loop mutants on α-factor-induced Ste2p internalization. Cells were treated with 10 nM 3H-α-factor for 20 min.

3.2. Potential phosphorylation sites on the C-terminus are need for ligand-induced internalization but negatively regulate signal transduction

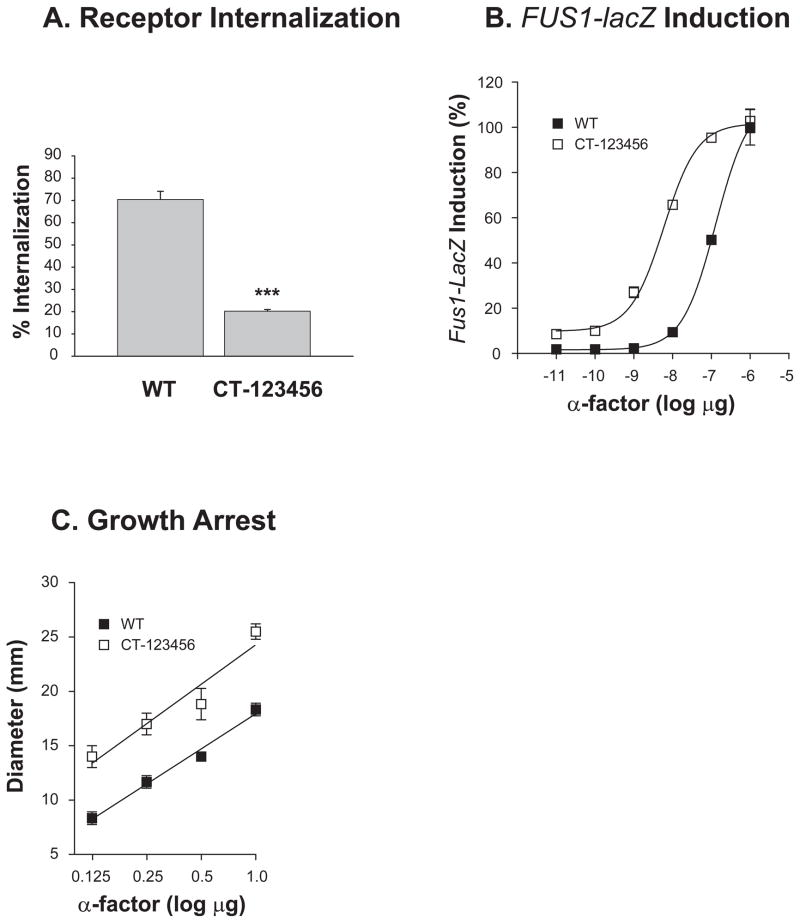

The C-terminal region of Ste2p consists of 135 amino acids (residues 296 to 431), of which 15 are serine and 18 are threonine residues. WT and CT-123456, in which all of S/T residues were mutated (Fig. 1 & Table I), showed the same expression levels when evaluated by ligand binding with 3H-α-factor. Agonist-induced Ste2p internalization was inhibited by 3- to 4-fold compared to WT (Fig. 3A). CT-123456 showed an increase in the basal level and sensitivity to α-factor, as judged using the FUS1-lacZ signaling assay (Fig. 3B) and the halo growth arrest assay (Fig. 3C). The basal level of FUS1-lacZ activity in the CT-123456 mutant was markedly increased to four times that of the basal level of the WT, and the amount of pheromone required to give one-half of the maximal response was about 22 times less for CT-123456 in comparison to that of the WT.

Fig. 3. Effect of mutation of all potential Ser and Thr phosphorylation sites in the C-terminus on ligand-induced internalization and signaling.

(A) Ligand-induced internalization of the CT-123456 Ste2p mutant and WT Ste2p is shown. Cells were treated with 10 nM 3H-α-factor for 20 min.

(B) FUS1-lacZ induction of the CT-123456 Ste2p mutant and WT Ste2p is shown.

(C) Growth arrest assay of the CT-123456 Ste2p mutant and WT Ste2p is shown. For some assay points the error bars are contained within the symbol.

3.3. Signaling by Ste2p is altered by mutation of Ser and Thr residues in the C-terminus

Since a Ste2p construct containing mutations in the entire C-terminus (CT-123456) showed an increase in the basal level and sensitivity to α-factor as judged using the FUS1-lacZ signaling assay (Fig. 3B) and the halo growth arrest assay (Fig. 3C), FUS1-lacZ and growth arrest experiments on members of the CT-mutant series (Table 1) were carried out in order to determine whether the potential phosphorylation sites located within specific regions of Ste2p were involved in the regulation of signaling.

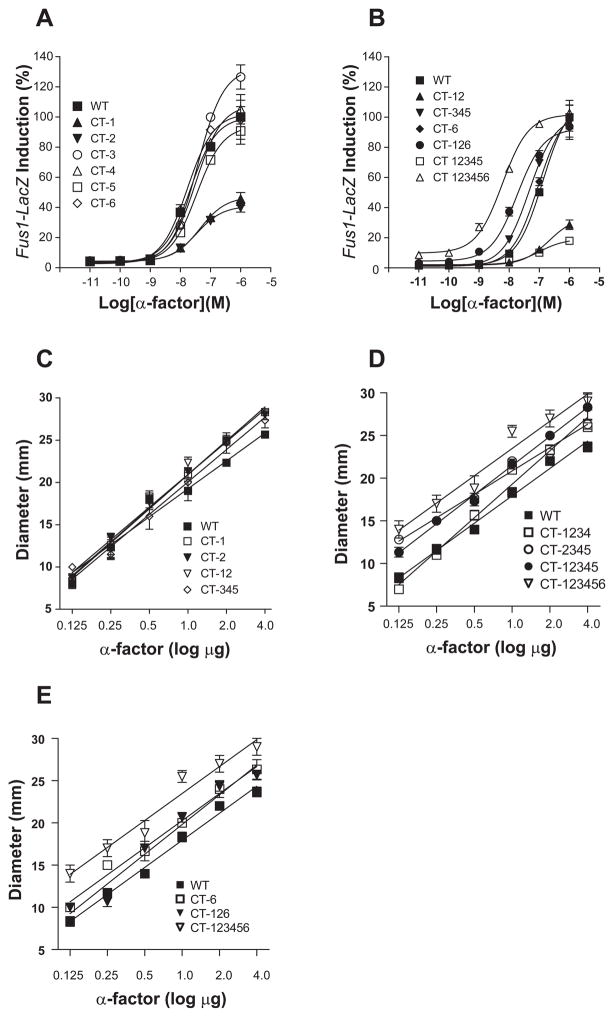

Constructs containing mutations in CT-1, CT-2, CT-3, CT-4, CT-5, and CT-6 led to various levels of α-factor-induced FUS1-lacZ induction in comparison to the WT (Fig. 4A). Mutants CT-1 and CT-2 were markedly impaired with respect to maximal and half-maximal response to pheromone, although signaling in the absence of pheromone (basal signaling) was the same as that of the WT. The total response was approximately 40% of the WT response, whereas the EC50 values were 1.5 to 2-fold higher. CT-3, CT-4, CT-5, and CT-6 were similar to WT in pheromone response, although the maximal response of CT-3 was somewhat higher (1.3 times higher than WT), and EC50 values of those mutants slightly increased (CT-3, CT-4, CT-5: 1.2–1.5 times that of WT) or decreased (CT-6, about 20% decrease). Those results indicate that putative phosphorylation sites in CT-1 and CT-2 regions of Ste2p play a critical role in the agonist-induced signaling of Ste2p that was assessed by FUS1-lacZ assay. We further investigated the roles of regions CT-1 and CT-2 in signaling by combining those mutations with mutations in other regions.

Fig. 4. Effect on signaling of removal of potential Ser and Thr phosphorylation sites in regions of the C-terminus.

(A) Effect of Ser and Thr mutations in individual CT regions on FUS1-lacZ induction.

(B) Effect of Ser and Thr mutations in combined CT regions on FUS1-lacZ induction.

(C) Effect of Ser and Thr mutations in CT-1 and CT-2 regions on growth arrest.

(D) Effect of Ser and Thr mutations in combined CT-12 and CT-345 regions on growth arrest.

(E) Effect of Ser and Thr mutations in combined CT-12 and CT-6 regions on growth arrest. All data in (A) and (B) are expressed as a percentage of the WT control normalized to 100%. For some assay points the error bars are contained within the symbol.

CT-12 or CT-12345 gave phenotypes (Fig. 4B) similar to that observed for either CT-1 or CT-2 alone (Fig. 4A). Simultaneous mutations in CT-1 and CT-6 (CT-16) or CT-2 and CT-6 (CT-26) showed the same FUS1-lacZ response as CT-1 or CT-2 (unpublished data). In contrast, the response of CT-126 to pheromone was greatly restored compared to CT-12 alone, with 2.7 times increase in the maximal response and 12 times decrease in the E50 value compared to CT-12 (Fig. 4B). CT-126 showed 16 times higher sensitivity to α-factor and had an approximate 2-fold increase in basal level of signaling compared to WT. Mutations in CT-345 caused an increase in sensitivity to ligand, as shown by a leftward shift in the dose-response curve; the EC50 value decreased 2.8 times compared to WT (Fig. 4B). This shift was not observed when CT-3, CT-4, or CT-5 was individually mutated (Fig. 4A). Combining mutations in regions 1, 2, and 6 with 3, 4, and 5 (CT-123456) led to further increased signaling, as indicated by a marked leftward shift in the dose-response curve and a 4-fold increase in basal-level signaling, as shown in Fig. 2B & 4B. Those results suggest that mutation of S/T residues located within the central region (CT-345) and the proximal regions (CT-12) exert beneficial and detrimental effects, respectively; simultaneous mutations of S/T residues located within proximal and distal areas (CT-12 and CT-6) overcome negative effects through CT-12.

Next, we tested those CT mutants for growth arrest (halo assay), another representative functional assay of Ste2p. In contrast to their behavior in the FUS1-lacZ assay, all of the mutants tested, which included CT-1, CT-2 and CT-12, were fully functional in the halo assay (Fig. 4C). Thus, it appears that mutations of the potential phosphorylation sites in CT-1 and CT-2 result in different functional consequences with respect to signaling. Unlike FUS1-lacZ induction assay, in which synergistic or antagonistic activities were observed for specific mutations, the growth arrest activity of each mutant increased as the number of mutated S/T residues was increased. For example, as CT-345 was added to CT-2, CT-12, or CT-126, the growth arrest activity of the corresponding mutant was significantly increased (p<0.01 compared to WT at 4 μg αfactor) (Fig. 4D&E). Those results suggest that, although they have been considered to represent the same signaling pathway of Ste2p, FUS1-lacZ assay and grow arrest assay might employ different molecular mechanisms and exert distinct functional consequences.

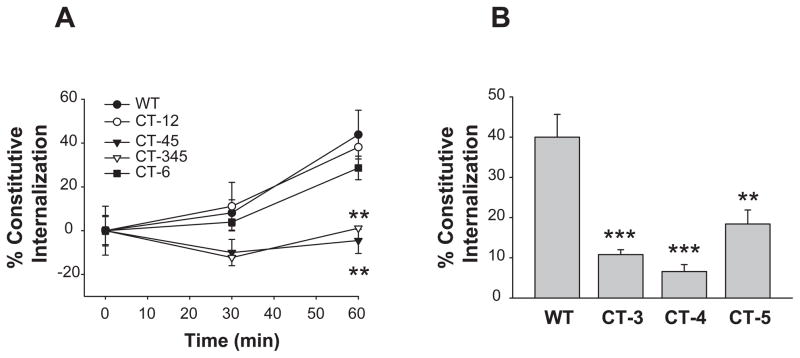

3.4. Constitutive internalization is redundantly controlled by Ser/Thr residues in the central region of the C-terminus

The internalization of Ste2p consists of two components: an agonist-independent (constitutive) and an agonist-induced internalization (4). In order to test whether the S/T residues in various CT regions differently regulate constitutive and ligand-induced internalization, selected mutants were treated for two different internalizations. To measure the constitutive internalization, cells were treated with cycloheximide to block de novo synthesis of Ste2p, and the disappearance of Ste2p from the plasma membrane was measured in the absence of added pheromone. Constitutive internalization of Ste2p was much slower than ligand-induced internalization. Only negligible extent of constitutive internalization was observed at 15 min, at which about 60% of ligand induced internalization was observed (Fig. 6A). We found that the constitutive internalization of Ste2p was not affected significantly (p>0.5) by mutations in CT-12 or CT-6 (Fig. 5A). For WT, CT-12, and CT-6, approximately one-half of the receptors were cleared from the cell surface over the one-hour assay interval. In contrast, CT-345 and CT-45 showed a significant reduction (p<0.02) in constitutive internalization, and there was essentially no loss of receptor from the cell surface. When the S/T residues located within CT-3, CT-4, and CT-5 region were individually mutated, the constitutive internalization of Ste2p was also significantly inhibited (Fig. 5B). It was reported previously that mutation of the serine residues in the S331INNDAKSS339 sequence, a region that overlaps CT-3 (D335-Y348), was sufficient to abolish constitutive internalization of Ste2p (4). Our results indicate that regions other than 331–339 are also involved in constitutive internalization of Ste2p, and that the domains responsible for constitutive internalization cannot be separated from those for agonist-induced internalization.

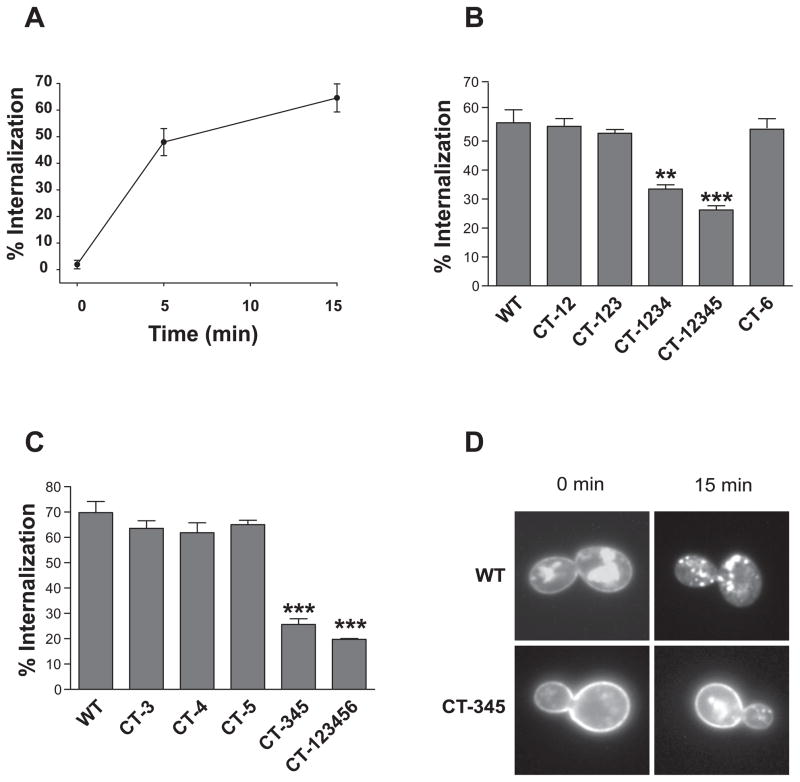

Fig. 6. Effects of mutations of the potential phosphorylation sites located within the C-terminus on α-factor-induced Ste2p internalization.

(A) Time course of α-factor-induced internalization of Ste2p.

(B, C) Internalization was determined for each of the various CT mutants, where all the serine and threonine residues in the regions of the C-terminus were replaced with alanines. Cells were treated with 10 nM 3H-α-factor for 15 min (B) or 20 min (C). *: p<0.05 compared to the WT group **: p<0.01 compared to WT group; ***: p<0.001 compared to WT group.

(D) Fluorescence microscope images of GFP-tagged Ste2p α-factor treated cells. The cells were observed in the absence of α-factor (0 min) and following treatment with 10 nM α-factor for 15 and 60 min at 30°C prior to imaging.

Fig. 5. Roles of phosphorylation sites located within the C-terminus on the constitutive internalization of Ste2p.

(A) The percent internalization shown in the figure represents the fraction of receptors removed from the cell surface at 30 min and 60 min incubation intervals in the presence of cycloheximide. Following incubation, the number of receptors remaining on the cell surface was determined by a ligand binding assay. **: p<0.02 compared to the WT group.

(B) The constitutive internalization was determined at 60 min. **:p<0.01, ***:p<0.001 compared to the WT group.

3.5. Ligand-induced receptor internalization is decreased upon mutation of Ser and Thr residues in the central regions of the C-terminus

Ligand-induced internalization of Ste2p was a rapid process; more than 40% of Ste2p on the cell surface translocated to cytosolic region within 5 min (Fig. 6A). Ligand-induced Ste2p internalization was significantly inhibited when all serine and threonine residues in the C-terminus were mutated to alanine (CT-123456, Fig. 2A). To further specify the potential phosphorylation sites responsible for α-factor-induced internalization in the C-terminus, various mutants shown in Fig. 1 were tested. Mutations in CT-1 or CT-2 separately (unpublished data), in combination with each other (CT-12), or with CT3 (CT-123) had no effect on Ste2p ligand-induced internalization, nor did mutations in CT-6 (Fig. 6B). In contrast, a decrease in ligand-induced internalization was observed when mutations were made to include CT-3 and -4 (CT-1234; p<0.05) and further increased when CT-5 was additionally included (CT-12345; p<0.01; Fig. 6B). The role of regions 3, 4, and 5 was further analyzed by introducing mutations in each individual region (Fig. 6C), and it was found that the combination of CT-3,-4, or -5 was needed to inhibit the internalization of Ste2p (Fig. 6B&C). The extent of ligand-induced internalization of CT-345 mutant was similar to that of the CT-123456 mutant, suggesting that CT-345 is largely responsible for the α-factor-induced internalization of Ste2p.

Those results were further corroborated by microscopy studies, in which the internalization of receptors tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) was determined. Before treatment with pheromone (Fig. 6D, upper left panel), WT Ste2p-GFP was observed associated with the plasma membrane and with intracellular compartments. Upon treatment with α-factor (30 nM, 15 min), the majority of Ste2p was not present in the plasma membrane but was found in punctuate cytoplasmic distribution (Fig. 6D, lower left panel). In contrast, the CT-345-GFP Ste2p was localized primarily to the plasma membrane in the resting state (Fig. 6D, upper right panel), and α-factor treatment only slightly increased its intracellular distribution (Fig. 6D, lower right panel).

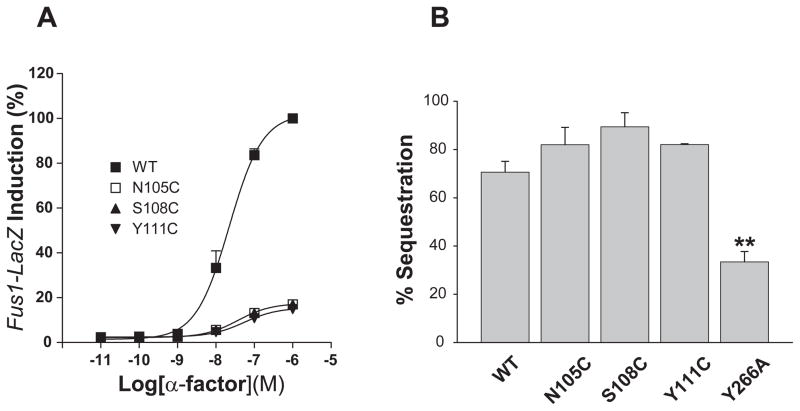

3.6. Receptor signaling is not a prerequisite for Ste2p internalization

To investigate whether internalization was also affected in the mutants, we employed several Ste2p mutants that have normal ligand binding properties but altered signaling activities. The N-terminal half of the 1st extracellular loop (EL-1) of Ste2p is reported to exist as a 310 helix, followed by a short β-sheet on the C-terminal half of the loop. The mutations N105C, S108C, and Y111C within EL-1 cause defective signaling without altering ligand binding properties (17). If signaling is a prerequisite for internalization, agonist-induced internalization might not occur in those mutants. Mutants N105C, S108C, and Y111C showed approximately 20% of the FUS1-lacZ induction activity compared to WT Ste2p (Fig. 7A) in accordance with results reported previously. The percentage internalization of the three mutants was approximately 75%, which is virtually identical to the WT (Fig. 7B), suggesting that EL-1 is involved in signaling but not the internalization of Ste2p. However, a mutant in the sixth transmembrane domain (Y266A) with markedly reduced FUS1-lacZ signaling capacity (20) showed impaired internalization (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the residue of the receptor influences both signaling and internalization.

Fig. 7. Different requirements for Ste2p signaling and internalization in non-CT residues.

(A) Effects of point mutations in the 1st extracellular loop on FUS1-lacZ reporter gene induction. Data are expressed as a percentage of the WT control normalized to 100%.

(B) Effects of point mutations in the 1st extracellular loop and in TM6 (Y266A) on αfactor-induced internalization of Ste2p. **: p<0.01 compared to the WT group. For some assay points the error bars are contained within the symbol.

4. Discussion

The molecular mechanisms involved in the G protein signaling and receptor internalization have been extensively characterized for the Ste2p, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae pheromone receptor (21–23). The portions of Ste2p residing within the cytoplasm are important for signaling and internalization. In particular, roles of the phosphorylation on the S/T residues in the certain parts of C-terminus were emphasized for the internalization of Ste2p (4, 24). In this study, we conducted a systematic investigation of the influence on signaling and internalization of all putative S/T phosphorylation sites in the intracellular loops and C-terminus of Ste2p.

The results reported in this paper suggest that many of the S/T residues in the C-terminus of Ste2p, which can be phosphorylated by intracellular kinases, are essential for receptor signaling and internalization. The phosphorylation of the critical S/T residues in the C-terminus of Ste2p is supported by several phosphoproteome studies, in which constitutively phosphorylated residues on Ste2p were identified in regions CT-2 (S331), CT-3 (S338 and S339) (25), CT-4 (S366) (25–27), CT-5 (T382, T384, and S385) (27, 28), and CT-6 (T411 and T414) (28). In addition, biochemically-based experiments postulated that six serine residues in the SINNDAKSS motif and some of S/T residues located within CT-3/CT-4 could be phosphorylated by pheromone addition (4, 9). In another study, constitutive phosphorylation of S/T residues in CT-6 was demonstrated in a mutant Ste2p, in which the extreme C-terminus (residues 391 to 431) was fused to the seventh transmembrane domain, leaving only S398, T411, T414, and T425 residues available for phosphorylation (24). Those results are summarized in the graphic abstract.

The potential phosphorylation sites in CT-1 or CT-2 were shown to be important for the signaling of Ste2p, which was measured by FUS1-lacZ induction (Fig. 4A&B), but not for either internalization (Fig. 5&6B) or the signaling measured by growth arrest (Fig. 4C). CT-1 and CT-2 of Ste2p were reported to have a tendency to form an α-helix-like structure in membrane mimetic environments (29). This so-called “eighth helix,” which was identified in the crystal structure of various GPCRs such as rhodopsin (30) and the β-adrenergic receptor (31–33), has been shown to play multiple roles in signaling of certain GPCRs such as bradykinin receptor (34). In accordance with this, the eighth helix region of Ste2p physically interacts with the G protein (35, 36) to form a pre-activation complex (7), suggesting that the S/T residues in that structural motif might play important roles in the α-factor-induced activation of Ste2p.

Previous studies (4, 9) showed that only 20–30% of the ligand-induced internalization of Ste2p was inhibited by mutation of six serine residues located within the S331INNDAKSS339 sequence and some of S/T residues located within CT-4, and our results (Fig. 6B-C) confirmed that additional mutations of S/T residues in CT-4/CT-5 are needed for more complete inhibition of ligand-induced internalization. These results suggest that the ligand-induced internalization of Ste2p is likely to be inhibited by exclusive mutation of S/T residues located within CT-45, and that there could be synergistic activities between CT-3 and CT-45.

When constitutively phosphorylated S/T residues are counted out, the candidate S/T residues that can be phosphorylated in response to α-factor are T354, T355, T363, T368, S386, and T389. It is noticeable that more extensive mutations of S/T residues are needed to inhibit the ligand-induced internalization than constitutive internalization of Ste2p. If one hypothesizes that a certain level of phosphorylation is required for receptor internalization given the lower level of Ste2p phosphorylation in the basal state, constitutive internalization might be further reduced by individual mutations in phosphorylation sites within CT-345. However, as receptor phosphorylation increases upon α-factor stimulation, a more extensive decrease in the receptor phosphorylation might be required for the inhibition of the agonist-induced internalization of Ste2p. In support of this idea, impairment of the internalization of the β2-adrenergic receptor by a point mutation in the consensus motif NPXXY motif was overcome by increasing the receptor phosphorylation by co-expression of the GRK2 (37).

In addition to those discrete roles of different domains in the C-terminus, there was functional interaction between the domains. For example, mutations of S/T residues within CT-1 and CT-2 greatly impaired the signaling of Ste2p (Fig. 4A), but the additional mutation of S/T residues within CT-6 but not CT-345 reversed the detrimental effects of CT-12 on the signaling of Ste2p, showing that CT-6 but not CT-345 has functional interaction with CT-12. When the S/T residues within CT-345 were additionally mutated, the signaling efficiency of CT-126 was further enhanced, suggesting that there is functional interaction between CT-345 and CT-6. These results overall suggest that there is functional interaction between CT-12 and CT-6, CT-346 and CT-6, but not between CT-12 and CT-345 when the signaling of Ste2p was measured by FUS1-lacZ induction.

It is noticeable that the phosphorylation status of CT-6 somehow antagonized the detrimental effects of CT-1 and CT-2 phosphorylation mutants only when both CT-1 and CT-2 are mutated. It was reported that S/T residues located within CT-6 are constitutively phosphorylated (24) but some of S/T residues located within CT-12 are phosphorylated in response to agonist stimulation (4). These results suggest that the signaling of Ste2p can be regulated by different phosphorylation/dephosphorylation kinetic profiles of S/T residues which might have different selectivity toward different protein kinases.

It was reported the constitutive desensitization of Ste2p is mediated by constitutive phosphorylation S/T residues located within CT-6 (24). This is in agreement with our results, that is, mutation of the S/T residues located within CT-6 shifts the dose-response curve to the left (Fig. 4B). In case of CT-3, CT-4, and CT-5, the S/T residues located within these regions are phosphorylated in response to agonist stimulation (9). As in CT-6, mutation of S/T residues located within CT-3, CT-4, and CT-5 domain shifted the dose-response curve to the upper left (Fig. 4B&E), suggesting that phosphorylation of these S/T residues are involved in the agonist-induced desensitization of Ste2p. These results suggest that increase in the signaling of efficiency in CT mutants could be caused by abolishment of constitutive and agonist-induced desensitization of Ste2p.

Interestingly, we noted differences between two bioassays that were employed for determination of the signaling of Ste2p. CT-1, CT-2, or CT-12 showed low activities for signaling of Ste2p, as measured by gene induction, but were fully active in the growth arrest assay (Fig. 4). It could be speculated that the coupling specificity or regulatory mechanisms could be different depending on the conformation of Ste2p. Other studies with Ste2p have indicated that the phosphorylation state of the C-terminus influences the nature, duration, and specificity of signaling response (38). Perhaps the differential density of phosphorylated S/T residues contained in helix 8 regulates the conformation al status of Ste2p, which determines the specificity of the signaling pathways or differential involvement of regulatory mechanisms. The importance of phosphorylation of the intracellular regions of receptors that mediate distinct signaling outcomes has been observed for other GPCRs (39).

We also examined residues in regions other than the C-terminus to address the issue of whether signaling is required for the internalization to occur. In our study, the signaling and internalization were either distinct or overlapping events depending on the specific residue examined. For example, intact EL-1 was clearly required for efficient receptor signaling but not for receptor internalization, suggesting that the signaling and internalization are independent processes. On the other hand, mutation at Y266, which is known to have reduced signaling activities (40), showed decreased α-factor-induced Ste2p internalization, supporting the contention that internalization and signaling are coupled (41). Overall, those results show that the signaling and internalization of Ste2p are not directly coupled. Those results are in agreement with previous studies, which showed that the signaling and internalization of GPCRs occur independently (42, 43).

5. Conclusions

We defined distinct functional regions in the cytoplasmic C-terminus of Ste2p that contain residues responsible for internalization and signaling of full length Ste2p. The regions proximal to the seventh transmembrane domain were dominant for ligand-induced signaling, whereas the middle regions 3, 4, and 5 controlled the internalization, and the distal region 6 appeared to influence constitutive signaling. Whether the tail regions interact with each other or regulate activities by their interactions with cytoplasmic proteins was not directly determined. However, the ability of mutation in CT-6 to suppress the phenotype exhibited by Ste2p mutated in CT-1 and CT-2 suggests that those regions of the receptor either come together to form a functional microdomain or that they interact cooperatively with downstream elements involved in either signaling or receptor internalization. Functional consequences of these mutants are summarized in Table II.

Table II.

Summary of Relative Functional Assay Results on Step C-terminal Tail Mutants

| Mutant Ste2p | Ste2p Sequestration | FUS1-LacZ | Growth Arrest | Functional Summary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total1 | Basal | α-factor-induced | |||||||

| Max response2 | EC50 (μM) | Max response | Max response3 | EC50 (μM) | 0.125 μg | 0.5 μg | |||

| WT | 100 | 100 | 0.13 | 100 | 100 | 0.13 | 100 | 100 | |

| CT-12 | 110 | 29 | 0.21 | 95 | 32 | 0.21 | 91.4 | 115 | Ligand-induced G protein coupling |

| CT-345 | 42 | 98 | 0.045 | 105 | 96 | 0.046 | 112 | 125 | Internalization, regulate signaling |

| CT-6 | 100 | 98 | 0.091 | 109 | 101 | 0.091 | 120 | 119 | Maintain basal signaling low |

| CT-12345 | 45 | 27 | 0.11 | 97 | 29 | 0.11 | 136 | 123 | |

| CT-126 | 95 | 94 | 0.018 | 205 | 52 | 0.018 | 120 | 121 | Functional interactions |

| CT-123456 | 31 | 103 | 0.006 | 391 | 22 | 0.006 | 168 | 134 | |

total FUS1-lacZ activity = basal FUS1-lacZ activity + α-factor-induced FUS1-lacZ activity.

To calculate the relative maximum response, an increase in α-factor-induced fold of increase in FUS1-lacZ activity of each mutant Ste2p was calculated in relation to basal FUS1-lacZ activity of wildtype, then the maximum fold of increase in FUS1-lacZ activity of each Ste2p mutant was normalized for the maximum response of wildtype (100%).

To calculate the relative maximum response, an increase in α-factor-induced fold of increase in FUS1-lacZ activity of each mutant Ste2p was calculated in relation to basal FUS1-lacZ activity of each Ste2p mutant, then the maximum fold of increase in FUS1-lacZ activity of each Ste2p mutant was normalized for the maximum response of wildtype (100%).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Korean Research Foundation Grant by KRF-2010-0016112 (KM Kim) grants from the National Institute of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences to F.N (M22086) and to J.M.B.(M22087). We thank Ryan Markman (University of Tennessee) for technical support.

ABBREVIATIONS

- α-factor

tridecapeptide mating pheromone WHWLQLKPGQPNleY

- CT

C-terminal

- EL

extracellular loop

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- IL

intracellular loop

- MLT

medium lacking tryptophan

- NBD

nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl

- STE2

gene encoding the yeast pheromone receptor

- Ste2p

yeast mating pheromone receptor protein

- WT

wild type

- YPAD

yeast extract, peptone, adenine, dextrose

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this manuscript declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freedmanand NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:319–351. discussion 352–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krupnickand JG, Benovic JL. The role of receptor kinases and arrestins in G protein-coupled receptor regulation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:289–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefkowitz RJ, Hausdorff WP, Caron MG. Role of phosphorylation in desensitization of the beta-adrenoceptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:190–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90113-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicke L, Zanolari B, Riezman H. Cytoplasmic tail phosphorylation of the alpha-factor receptor is required for its ubiquitination and internalization. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:349–358. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Davis NG. Akr1p and the type I casein kinases act prior to the ubiquitination step of yeast endocytosis: Akr1p is required for kinase localization to the plasma membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5350–5359. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5350-5359.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reneke JE, Blumer KJ, Courchesne WE, Thorner J. The carboxy-terminal segment of the yeast alpha-factor receptor is a regulatory domain. Cell. 1998;55:221–234. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konopka JB, Jenness DD, Hartwell LH. The C-terminus of the S. cerevisiae alpha-pheromone receptor mediates an adaptive response to pheromone. Cell. 1988;54:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohrer J, Benedetti H, Zanolari B, Riezman H. Identification of a novel sequence mediating regulated endocytosis of the G protein-coupled alpha-pheromone receptor in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:511–521. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.5.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toshima JY, Nakanishi J, Mizuno K, Toshima J, Drubin DG. Requirements for recruitment of a G protein-coupled receptor to clathrin-coated pits in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:5039–5050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-07-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senand M, Marsh L. Noncontiguous domains of the alpha-factor receptor of yeasts confer ligand specificity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:968–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David NE, Gee M, Andersen B, Naider F, Thorner J, Stevens RC. Expression and purification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-factor receptor (Ste2p), a 7-transmembrane-segment G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15553–15561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abel MG, Zhang YL, Lu HF, Naider F, Becker JM. Structure-function analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae tridecapeptide pheromone using alanine-scanned analogs. J Pept Res. 1998;52:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1998.tb01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai H, Kauffman S, Naider F, Becker JM. Genomewide screen reveals a wide regulatory network for di/tripeptide utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2006;172:1459–1476. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding FX, Lee BK, Hauser M, Davenport L, Becker JM, Naider F. Probing the binding domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae alpha-mating factor receptor with rluorescent ligands. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1102–1108. doi: 10.1021/bi0021535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akal-Strader A, Khare S, Xu D, Naider F, Becker JM. Residues in the first extracellular loop of a G protein-coupled receptor play a role in signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30581–30590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raths SK, Naider F, Becker JM. Peptide analogues compete with the binding of alpha-factor to its receptor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17333–17341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman GA, Garrison TR, Dohlman HG. Analysis of RGS proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:617–631. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YH, Naider F, Becker JM. Interacting residues in an activated state of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2263–2272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riezman H. Down regulation of yeast G protein-coupled receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:129–134. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dohlmanand HG, Thorner JW. Regulation of G protein-initiated signal transduction in yeast: paradigms and principles. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:703–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dohlmanand HG, Slessareva JE. Pheromone signaling pathways in yeast. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:cm6. doi: 10.1126/stke.3642006cm6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Q, Konopka JB. Regulation of the G-protein-coupled alpha-factor pheromone receptor by phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:247–257. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodenmiller B, Campbell D, Gerrits B, Lam H, Jovanovic M, Picotti P, et al. PhosphoPep--a database of protein phosphorylation sites in model organisms. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;26:1339–1340. doi: 10.1038/nbt1208-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chi A, Huttenhower C, Geer LY, Coon JJ, Syka JE, Bai DL, et al. Analysis of phosphorylation sites on proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae by electron transfer dissociation (ETD) mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607084104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruhler A, Olsen JV, Mohammed S, Mortensen P, Faergeman NJ, Mann M, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics applied to the yeast pheromone signaling pathway. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ficarro SB, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Burke DJ, Ross MM, Shabanowitz J, et al. Phosphoproteome analysis by mass spectrometry and its application to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estephan R, Englander J, Arshava B, Samples KL, Becker JM, Naider F. Biosynthesis and NMR analysis of a 73-residue domain of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae G protein-coupled receptor. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11795–11810. doi: 10.1021/bi0507231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, et al. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Rosenbaum DM, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Edwards PC, et al. Crystal structure of the human beta2 adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2007;450:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, Moukhametzianov R, Edwards PC, Henderson R, et al. Structure of a beta1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swift S, Leger AJ, Talavera J, Zhang L, Bohm A, Kuliopulos A. Role of the PAR1 receptor 8th helix in signaling: the 7-8-1 receptor activation mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4109–4116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourne HR. How receptors talk to trimeric G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:134–142. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dosil M, Giot L, Davis C, Konopka JB. Dominant-negative mutations in the G-protein-coupled alpha-factor receptor map to the extracellular ends of the transmembrane segments. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5981–5991. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson SS, Menard L, Barak LS, Koch WJ, Colapietro AM, Caron MG. Role of phosphorylation in agonist-promoted beta 2-adrenergic receptor sequestration. Rescue of a sequestration-defective mutant receptor by beta ARK1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24782–24789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballon DR, Flanary PL, Gladue DP, Konopka JB, Dohlman HG, Thorner J. DEP-domain-mediated regulation of GPCR signaling responses. Cell. 2006;126:1079–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tobin AB, Butcher AJ, Kong KC. Location, location, location.. site-specific GPCR phosphorylation offers a mechanism for cell-type-specific signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee BK, Lee YH, Hauser M, Son CD, Khare S, Naider F, et al. Tyr266 in the sixth transmembrane domain of the yeast alpha-factor receptor plays key roles in receptor activation and ligand specificity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13681–13689. doi: 10.1021/bi026100u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benovic JL, Staniszewski C, Mayor F, Jr, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-Adrenergic receptor kinase. Activity of partial agonists for stimulation of adenylate cyclase correlates with ability to promote receptor phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3893–3897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zanolari B, Raths S, Singer-Kruger B, Riezman H. Yeast pheromone receptor endocytosis and hyperphosphorylation are independent of G protein-mediated signal transduction. Cell. 1992;71:755–763. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90552-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barak LS, Gilchrist J, Becker JM, Kim KM. Relationship between the G protein signaling and homologous desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:695–700. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]