Solid organ transplantation has become the therapy of choice for various types of organ failure. Two major complications, infection and malignancy, result from the lifelong immunosuppression needed to maintain allograft function. Most commonly, posttransplantation infections result from reactivation of latent infections in the donor organ or the recipient; Strongyloides stercoralis is one example of an organism that can exist in an asymptomatic host. The risk of reactivating a latent infection is related to the degree of post-transplantation immune suppression, particularly suppression of cell-mediated immunity. We describe a case of fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in a patient who had previously undergone orthotopic heart transplantation.

Case Report

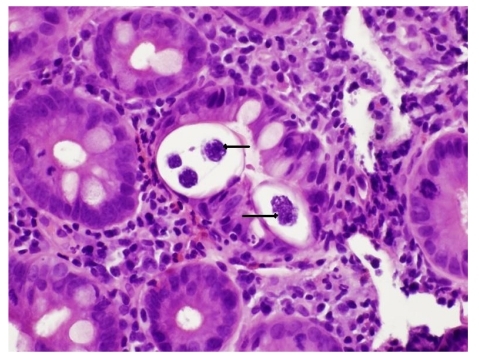

Our patient was a 51-year-old white male with a history of severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, emphysema, and hypothyroidism. After successful heart transplantation, the patient was placed on immunosuppressants, including corticosteroids, mycophenolate, and tacrolimus. The patient presented to us with severe nausea and vomiting 4 weeks after his transplantation. Initial diagnostic imaging showed unremarkable findings, and laboratory data were significant only for an elevated tacrolimus level (22.9 ng/mL; normal, 5–20 ng/mL). The patient's initial symptoms were attributed to supratherapeutic tacrolimus levels, but his nausea and vomiting persisted despite stopping tacrolimus treatment and use of antiemetics. The patient's disease course in the hospital deteriorated, with worsening dyspnea and hypoxemic respiratory failure. Acute transplantation rejection was ruled out via ventricular biopsies. A computed tomography scan of the chest revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities in both lung fields, prompting the performance of a bronchoscopy, which revealed signs suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage. The gastroenterology service was consulted for further work-up of the patient's unrelenting nausea and vomiting. A review of the patient's laboratory data revealed peripheral blood eosinophilia (up to 20%) for several months preceding the transplantation, which raised concerns of a parasitic infestation. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed, and mild erythema was found in the fundus and antrum of the stomach. Examination of up to the third portion of the duodenum was endoscopically unremarkable. Biopsies obtained from the duodenum and gastric antrum suggested active chronic duodenitis and chronic gastritis, with nematodes most suggestive of S. stercoralis visualized within the crypts (Figure 1). Ivermectin (stromectol, Merck) therapy was recommended. However, the patient died several days later.

Figure 1.

Duodenal biopsy showing Strongyloides stercoralis infection within the crypts (marked with arrows; hematoxylin and eosin stain, 200× magnification). The underlying lamina propria shows abundant neutrophils, eosinophils, and chronic inflammatory cells.

Discussion

S. stercoralis infection was first reported in 1876 in French soldiers. After approximately 50 years, more was known about the unique and characteristic feature of autoinfection that occurs in this parasite's life cycle.1 The earliest description of disseminated infection dates to 1966, when the first cases of fatal strongyloidiasis associated with immunosuppression were reported.2,3

Strongyloides is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas as well as in the Appalachian region of the United States, particularly eastern Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Immigrants and travelers from endemic areas and veterans of World War II and the Vietnam War are at risk for this infection. A prevalence rate of up to 4% has been reported for Strongyloides in the Southeastern United States.4,5

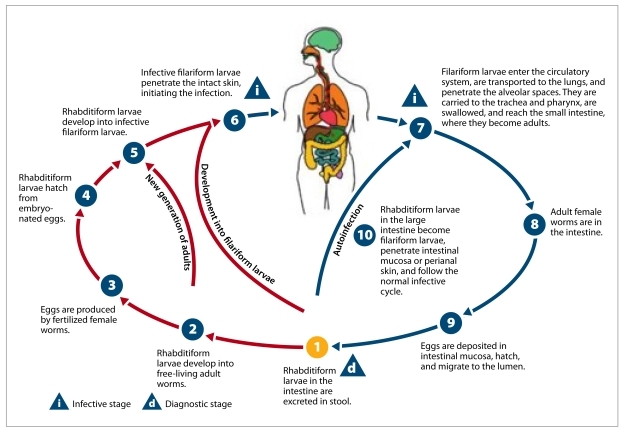

Strongyloidiasis is usually acquired via direct skin contact with filariform larvae. After entering a human host, the larvae migrate to the small intestine, where the female worm lays eggs that hatch into rhabditiform larvae. The larvae are either released into the stool or molt into filariform larvae that reinfect the host, resulting in chronic infection that can persist for several years (Figure 2). Peripheral eosinophilia is a frequent finding; it is seen in 50–80% of infested patients.6

Figure 2.

Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis.

Image from DPDx, Centers for Disease Control. Parasites and health: strongyloidiasis (Strongyloides stercoralis). http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/Strongyloidiasis.htm.

Once the host's immunity is compromised, the parasite exponentially increases in number, resulting in a potentially fatal hyperinfection syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by infective filariform larvae in the stool and sputum, leading to clinical manifestations of increased parasite load and migration (such as gastrointestinal bleeding, respiratory distress, and septic shock).7 The 2 most common settings associated with hyperinfection are corticosteroid treatment and human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 infection; however, cases of hyperinfection have also been reported in association with solid organ transplantation, hematologic malignancies, and AIDS. In fact, many cases of hyperinfection that have recently been reported in the literature involve solid organ transplantation recipients. Hyperinfection can develop months to years after transplantation, but severe disease usually occurs within the first 3 months.8

Prior to organ transplantation, patients are routinely evaluated for the presence of certain infections; however, screening for parasitic infection is not routine.8,9 We believe that patients from endemic areas and/or patients with risk factors for subclinical parasitic infestation should undergo further evaluation for the presence of active or latent infection before transplantation. In addition, systemic eosinophilia before transplantation should prompt a detailed work-up for parasitic infection.

Ivermectin (200 mcg/kg/day) is the treatment of choice for strongyloidiasis; albendazole (albenza, GlaxoSmithKline) is an alternative treatment option. In patients with hyperinfection or disseminated infection, treatment should be administered for at least 7–10 days or until symptom resolution.10 In immunocompromised hosts, the use of secondary prevention, such as a 2-day course of ivermectin every 2 weeks, may prevent hyper-infection or disseminated infection.11 In patients receiving steroids, curative treatment is difficult, and relapses of infection are common. Disseminated disease carries a mortality rate of almost 80%, so early detection and treatment are imperative.12

Our patient had peripheral eosinophilia prior to transplantation but was not evaluated for parasitic infestations; he likely had latent Strongyloides infection. He was a resident of the Southeastern United States, where S. stercoralis is endemic. The clinical outcome in our patient could have been different if S. stercoralis had been diagnosed and treated prior to transplantation. This case is an example of a potentially preventable infection in a patient undergoing organ transplantation.

Many cases of S. stercoralis infection are unrecognized, as diagnosis is often difficult. Diagnosis requires the examination of at least 2 stool specimens to check for the presence of rhabditiform larvae; testing of serial samples is recommended because of the low sensitivity of such testing. Larvae have also been identified in bronchial aspirates, sputum, serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and peritoneal fluid.13–18 Newer diagnostic methods include the luciferase immunoprecipitation system, which has increased sensitivity and specificity for the detection of S. stercoralis—specific antibodies, as well as real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing for the detection of S. stercoralis in fecal samples.19 Although detection of anti–S. stercoralis immunoglobulin G4 antibodies via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is sensitive, this method cannot distinguish between past or present infection, is cross-reactive with other helminthic infections, and can produce negative results in patients with disseminated infection.20

Conclusion

S. stercoralis hyperinfection is a potentially fatal complication of immunosuppression that should be suspected in every organ transplantation patient who presents with abdominal and/or respiratory symptoms. Instituting early therapy is of paramount importance; effective treatment consists of total eradication of the parasite before fatal complications develop. Therefore, knowledge of endemic areas is of considerable practical importance. Although current practice guidelines recommend screening for and treatment of Strongyloides infection before transplantation, physicians often miss opportunities to identify patients with chronic strongyloidiasis. Screening tests have limitations, so clinical suspicion remains an important component of the pretransplantation evaluation. Monthly prophylaxis in high-risk patients is a plausible alternative but is difficult to advocate, due to the low frequency of this disease, which makes cost-effectiveness studies challenging.21 Further studies are needed to define the benefits of routine prophylaxis in high-risk patients.

References

- 1.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040–1047. doi: 10.1086/322707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers WA, Jr, Nelson B. Strongyloidiasis and malignant lymphoma. “Opportunistic infection” by a nematode. JAMA. 1966;195:685–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz T, Reboucas G, Rocha H. Fatal strongyloidiasis in patients receiving corticosteroids. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:1093–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196611172752003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Concha R, Harrington W, Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203–211. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000152779.68900.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson W, Gerhardstein D, Thompson J. Disseminated Strongyloides stercoralis infection. South Med J. 1993;86:821–825. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199307000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genta R. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:755–767. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208–217. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.208-217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVault GA, Jr, King JW, Rohr MS, Landreneau MD, Brown ST, 3rd, McDonald JC. Opportunistic infections with Strongyloides stercoralis in renal transplantation. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:653–671. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan JS, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Opportunistic strongyloidiasis in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1986;42:518–524. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198611000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Igual-Adell R, Oltra-Alcaraz C, Soler-Company E, Sánchez-Sánchez P, Matogo-Oyana J, Rodríguez-Calabuig D. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin and thiabendazole in the treatment of strongyloidiasis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:2615–2619. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.12.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segarra-Newnham M. Manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1992–2001. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igra-Siegman Y, Kapila R, Sen P, Kaminski ZC, Louria DB. Syndrome of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:397–407. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SB, Schwartzman M, Mencia LF, et al. Fatal disseminated strongyloidiasis presenting as acute abdominal distress in an urban child. J Pediatr. 1977;91:607–609. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eveland LK, Kenney M, Yermakov V. Laboratory diagnosis of autoinfection in strongyloidiasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;63:421–425. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/63.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schainberg L, Scheinberg MA. Recovery of Strongyloides stercoralis by bronchoalveolar lavage in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1989;87:486. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith B, Verghese A, Guiterrez C, Dralle W, Berk SL. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis. Diagnosis by sputum gram stain. Am J Med. 1985;79:663–666. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams J, Nunley D, Dralle W, Berk SL, Verghese A. Diagnosis of pulmonary strongyloidiasis by bronchoalveolar lavage. Chest. 1988;94:643–644. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris RA, Jr, Musher DM, Fainstein V, Young EJ, Clarridge J. Disseminated strongyloidiasis. Diagnosis made by sputum examination. JAMA. 1980;244:65–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.244.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ten Hove RJ, van Esbroeck M, Vervoort T, van den Ende J, van Lieshout L, Verweij JJ. Molecular diagnostics of intestinal parasites in returning travelers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0745-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdalla J, Saad M, Myers JW, Moorman JP. An elderly man with immunosuppression, shortness of breath, and eosinophilia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1464–1536. doi: 10.1086/429724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul-Fattah MM, Nasr ME, Yousef SM, Ibraheem MI, Abdul-Wahhab SE, Soliman HM. Efficacy of ELISA in diagnosis of strongyloidiasis among the immune-compromised patients. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1995;25:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]