Strongyloides is a parasite that is very prevalent in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world and is endemic in the Southeastern United States.1–3 Strongyloidiasis is caused by the female nematode Strongyloides stercoralis.1–3 In its classic life cycle, Strongyloides travels from the skin to the lungs and then to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of its host. In hyperinfection syndrome, this classic life cycle is exaggerated (ie, the parasite burden and turnaround increase and accelerate).1,4 Disseminated disease is defined by the presence of parasites out-side of the traditional life cycle (ie, in organs other than the skin, GI tract, or lungs).4,5 Although hyperinfection syndrome can occur in any host, disseminated disease occurs mainly in immunocompromised individuals.4–6 Nonetheless, many experts equate hyperinfection syndrome with disseminated disease.7–9

The life cycle of Strongyloides is basically comprised of 2 parts: a free-living cycle outside of the host as rhabditiform larvae and a parasitic life cycle as infective filariform larvae (filariae).1–4 During the free-living cycle in the soil, Strongyloides transform from rhabditiform larvae into infective filariform larvae, which penetrate the human skin and proceed into the submucosa, then into the venous circulation, and then toward the right heart and lungs.1–3,5 During the maturation process, Strongyloides larvae induce alveolar capillary bleeding and potent eosinophilic inflammation, resulting in eosinophilic pneumonitis.1,3,5 From the alveoli, the larvae continue to migrate up the pulmonary tree and trachea. The cough reflex helps to push the larvae out of the bronchial tree and trachea. However, once the larvae reach the larynx, they are swallowed and travel to the stomach and small bowel.1,3 Inside the GI tract, Strongyloides larvae mature into diminutive adult females that measure approximately one tenth of one inch (ie, 220—250 μm).1,2 Adult female worms embed themselves in the mucosa of the small bowel and produce eggs via parthenogenesis. Within the intestinal lumen, the eggs hatch into noninfective rhabditiform larvae, which are excreted, along with stool, into the environment (ie, soil).1

A unique feature of some nematodes, including Strongyloides, is their ability to cause autoinfection. This means that the parasite never reaches the soil; instead, it re-enters the host via enteral circulation (endoautoinfection) or perianal skin (exoautoinfection).1–4 In addition, hands (eg, dirty fingers and fingernails) or food contaminated with stool can carry infective filariform larvae from the anus back to the host (the fecal-oral route). Thus, parasites can remain in the human body for the remainder of the host's life. One study found strongyloidiasis in a patient who had previously undergone colectomy for suspected ulcerative colitis10; this finding is important, as it demonstrates the occurrence of disease in a patient who no longer lived in an endemic area.1,11,12

Hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated strongyloidiasis can ensue in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity (such as transplant patients, patients receiving steroids or immunosuppressants, or patients infected with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1).5–9,13 As previously mentioned, hyperinfection syndrome represents an acceleration of the normal life cycle of S. stercoralis, leading to excessive worm burden within the traditional reproductive route (the skin, gut, and lungs), while disseminated strongyloidiasis involves widespread dissemination of larvae outside of the gut and lungs, often involving the liver, brain, heart, and urinary tract.4,6–9,13 Occasionally, strongyloidiasis is associated with gut translocation of bacteria and bacteremia.14,15 Commonly reported organisms include gram-negative rods such as Escherichia coli and gram-positive cocci such as Streptococcus bovis.14,15 Thus, the presence of S. bovis bacteremia should prompt a search for strongyloidiasis, in addition to a search for GI malignancies.14

The clinical presentation of hyperinfection syndrome is similar to that of classic strongyloidiasis, which includes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, GI hemorrhage, cough, fever, and dyspnea.1–13 However, due to increased parasite turnaround and dissemination, patients with hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease often have catastrophic clinical manifestations such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, meningitis, renal failure, and/or respiratory failure.6–9,13 This presentation was shown in the case reported by Grover and associates, in which a computed tomography scan of the chest revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities in both lung fields, prompting the performance of a bronchoscopy; the procedure noted signs suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage.13

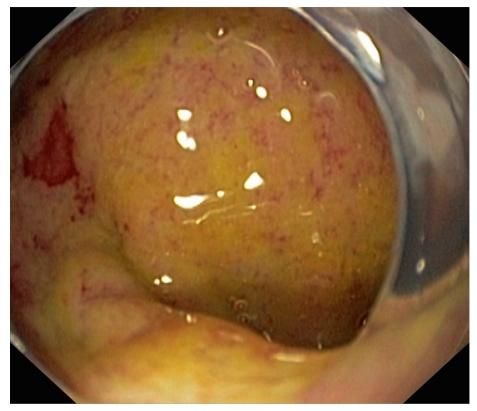

Diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome and/or disseminated disease can be very difficult to establish and entails a high level of suspicion.6–9,12,13 We believe that any immunosuppressed patient with eosinophilia who even briefly visits or lives in tropical or subtropical areas of the world or areas of the United States where Strongyloides is endemic should garner suspicion of possible strongyloidiasis. Some experts argue that the mere presence of eosinophilia is enough reason to search for this parasite.1,3,11,12 Although most studies focus on finding the parasite via stool examination (which has a yield that does not exceed 46%, even after 3 stool examinations), my colleagues and I focus on searching for the parasite in various tissues, particularly in the bronchi or GI tract.1–5 Indeed, due to the large parasitic burden present at the time of parasite dissemination, the yield in lung, bronchial, or small bowel biopsies is very high.3–6 In the case presented by Grover and coworkers, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed because of the patient's unrelenting nausea and vomiting, and mild erythema was found in the fundus and antrum of the stomach.10 Examination of up to the third portion of the patient's duodenum showed endoscopically unremarkable findings. Biopsies obtained from the patient's duodenum and gastric antrum suggested active chronic duodenitis and chronic gastritis, with nematodes most suggestive of Strongyloides stercoralis visualized within the crypts.13 The endoscopic manifestations of strongyloidiasis are broad, ranging from normal-appearing mucosa to ulcerative and catarrhal duodenitis (Figure 1).3 Patients with a clinical and histopathologic diagnosis of "idiopathic" eosinophilic gastroenteritis should also be thoroughly evaluated for Strongyloides because larvae may not always be apparent on initial evaluation, and therapy with corticosteroids may lead to fatal hyperinfection if the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis is missed.3 Thus, evaluation should include several stool examinations and EGD procedures with duodenal biopsies. Multiple biopsy specimens should be taken to increase the histopathologic yield, even if the duodenal mucosa does not manifest any major abnormalities.3 Biopsy specimens should be reviewed by an expert GI pathologist, as false-negative interpretations have been reported in which retrospective examination yielded a diagnosis of Strongyloides infection.16

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of the duodenal bulb in a patient with Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome. Note the diffuse mucosal swelling, erythema, and massive mucopurulent secretion on top of the mucosa.

The first-line therapy for strongyloidiasis is ivermectin (stromectol, Merck), which achieves eradication rates of approximately 80%.1–5 Other effective agents include thiabendazole (mintezol, Merck) and albendazole (albenza, GlaxoSmithKline).1–9,11 Often, a single course of treatment is insufficient. Thus, if symptoms do not resolve after the initial therapy, it is imperative that diagnostic studies (stool, duodenal fluid, and/or endoscopy) be repeated to determine the persistence of the Strongyloides infection and whether a second course of therapy should be given. Resolution of eosinophilia does not always indicate clearance of Strongyloides.3 Because it is difficult to clinically confirm eradication of the infection, many experts prefer to repeat a 2-day course of therapy 1 week after the initial course, with careful follow-up in patients with persistent symptoms and/or infection.3,17

Because of the often lethal course of disseminated strongyloidiasis, a strong case can be made that clinicians should search for this parasite in patients awaiting transplantation.2 Indeed, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Society of Transplantation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Society of Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation recommend testing for Strongyloides immunoglobulin G enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay antibodies in patients from endemic areas and patients with unspecific GI symptoms or eosinophilia before solid organ or hematopoietic transplantation is performed.2,18 Unfortunately, screening for this parasitic infection is still not a routine practice, and physicians often miss opportunities to identify patients with chronic strongyloidiasis, as occurred in the case reported by Grover and colleagues.13

Summary

Strongyloidiasis can involve many organs and, therefore, can have unspecific and unusual clinical manifestations, making the infection difficult to diagnose. Furthermore, lack of familiarity with this condition can have catastrophic consequences. Due to its unique life cycle, Strongyloides is capable of infecting a host until death of the host. Strongyloidiasis can be a severe disease, causing both hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease, particularly in transplantation patients. Thus, any patient who came from or traveled to an endemic area of the world may potentially be infected with this parasite, particularly if symptoms and blood and/or tissue eosinophilia are present. Clinicians should search for strongyloidiasis in any patient awaiting transplantation who has epidemiologic risk factors or clinical or laboratory signs of the condition.

References

- 1.Liu LX, Weller PF. Strongyloidiasis and other intestinal nematode infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7:655–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roxby AC, Gottlieb GS, Limaye AP. Strongyloidiasis in transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1411–1423. doi: 10.1086/630201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson BF, Fry LC, Wells CD, et al. The spectrum of GI strongyloidiasis: an endoscopic-pathologic study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:906–910. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcos LA, Terashima A, Dupont HL, Gotuzzo E. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an emerging global infectious disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganesh S, Cruz RJ., Jr Strongyloidiasis: a multifaceted disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:194–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fardet L, Généreau T, Poirot JL, Guidet B, Kettaneh A, Cabane J. Severe strongyloidiasis in corticosteroid-treated patients: case series and literature review. J Infect. 2007;54:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porto AF, Neva FA, Bittencourt H, et al. HTLV-1 decreases Th2 type of immune response in patients with strongyloidiasis. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:503–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asdamongkol N, Pornsuriyasak P, Sungkanuparph S. Risk factors for strongyloidiasis hyperinfection and clinical outcomes. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:875–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffer MW, Buell JF, Gupta M, Conway GD, Akhter SA, Wagoner LE. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry AJ, Long EG, Smith JH, Gourley WK, Fine DP. Chronic relapsing colitis due to Strongyloides stercoralis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1289–1293. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Genta RM. Global prevalence of strongyloidiasis: critical review with epidemiologic insights into the prevention of disseminated disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:755–767. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirisi M, Salvador E, Bisoffi Z, et al. Unsuspected strongyloidiasis in hospitalised elderly patients with and without eosinophilia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:787–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grover IS, Davila R, Subramony C, Daram SR. Strongyloides infection in a cardiac transplant recipient: making a case for pretransplantation screening and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:763–766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linder JD, Mönkemüller KE, Lazenby AJ, Wilcox CM. Streptococcus bovis bacteremia associated with Strongyloides stercoralis colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:796–798. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smallman LA, Young JA, Shortland-Webb WR, Carey MP, Michael J. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfestation syndrome with Escherichia coli meningitis: report of two cases. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:366–370. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.4.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez Y, Bhatia P, Garbadawala ST, Dobson JR, Wallace TM, Carey TE. Strongyloides stercoralis eosinophilic granulomatous enterocolitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:603–612. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 2nd ed. New Rochelle, NY: The Medical Letter, Inc; 2002. pp. 1–12.http://www.medletter.com/freedocs/parasitic.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Infectious Disease Society of America, American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Guidelines for preventing opportunistic infections among hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. MMWRRecomm Rep. 2000;49:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S1083-8791(00)70002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]