Abstract

Background

Because Medicare policy restricts simultaneous Medicare hospice and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care, we compared hospice use and sites of death for SNF/non-SNF residents with advanced dementia; and, for those with SNF, we evaluated how subsequent hospice use was associated with dying in a hospital.

Methods

This study includes (non-health maintenance organization [HMO]) residents of U.S. nursing homes (NHs) who died in 2006 with advanced dementia (n=99,370). Sites of death, Medicare SNF, and hospice use were identified using linked resident assessment and Medicare enrollment and claims data. Advanced dementia was identified by a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or dementia on the Minimum Data Set (MDS) or a Medicare claim in the last year of life and severe to very severe cognitive impairment (5 or 6 on the MDS cognitive performance scale). For residents with SNF, we used multivariate logistic regression with generalized estimating equations to estimate the effect of subsequent hospice enrollment on dying in a hospital.

Results

Forty percent of U.S. NH residents dying with advanced dementia in 2006 had SNF care in the last 90 days of life. Those with versus without SNF less frequently used hospice (30% versus 46%), more frequently had short (≤7 days) hospice stays (40% versus 19%), and more frequently died in hospitals (14% versus 9%). Among residents with SNF, those with subsequent hospice use had a 98% lower likelihood of a hospital death (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.014, 0.025).

Conclusions

Dual hospice/SNF access may result in fewer hospital deaths and higher quality of life for dying NH residents.

Introduction

In 2001, 67% of U.S. older adults with dementia who died did so in nursing homes (NHs).1 Studies have shown high proportions of persons dying in NHs with dementia have distressing symptoms and burdensome interventions.2–7 NH hospice care has been found to provide benefits to dying NH residents, including better pain management,8 fewer hospitalizations,9 and greater family satisfaction with end-of-life (EoL) care,10–12 and the benefits of hospice have been shown to extend to residents with dementia.8,9,13 Although the proportion of dying NH residents with advanced dementia accessing hospice almost tripled between 1999 and 2006 (to approximately 40%),14 there remain important barriers to greater and timelier hospice access.15,16 A major barrier is the Medicare policy disallowing simultaneous access to Medicare Part A hospice care for NH residents receiving Medicare skilled nursing facility (SNF) care (when SNF care is for the terminal condition).17 However, how this policy is associated with hospice use at the EoL has not been evaluated.

For persons with advanced dementia who are admitted/readmitted to NHs after hospitalizations, Medicare SNF care is common (even if actively dying). Post hospitalizations, residents qualify for SNF care when changes in their conditions are likely and thus require skilled observation and assessment or when they are prescribed complex services (e.g., intravenous feedings, intramuscular injections, other) or therapies that require skilled nursing or rehabilitation staff supervision.18 However, because 12% of residents die within 90 days of a SNF admission,19 whether or not palliative care expertise is available for Medicare SNF residents is of concern. This concern is heightened given the presence of financial incentives associated with the choice of Medicare SNF versus hospice. For private-pay residents, residents and families may be hesitant to choose hospice because they would lose the (substantial) Medicare co-payment for SNF care. For Medicaid residents, NHs differ in their willingness to suggest hospice for residents receiving Medicare SNF care because with hospice enrollment NH payment converts to the much lower Medicaid per diem versus the higher Medicare per diem. Whereas much concern has been voiced about the quality implications of this Medicare SNF policy,17,20 no research to date has examined EoL care and outcomes for dementia decedents who had SNF NH admissions near the EoL.

In addition to discouraging hospice enrollment, the inability of NH residents with advanced dementia to simultaneously access Medicare hospice and SNF care may also contribute to later hospice referrals (because of the financial disadvantages of the required abandonment of SNF). Furthermore, SNF residents who are unable to access hospice may be more likely to die in a hospital. Hospitals are generally not the preferred location for the site of death among the frail elderly, and in many cases hospitalizations are potentially avoidable.21 Hospice enrollment is known to be associated with lower hospital use for dying NH residents9 and previous research has shown that 33.5% of NH residents dying within 30 days of a SNF admission die in a hospital.22 Unknown is how hospice use (and timing of referrals) may differ when SNF admission occurs near death and how hospice use subsequent to SNF may influence the probability of a terminal hospitalization.

To better understand the influence of the Medicare policy prohibiting simultaneous Medicare hospice and SNF (when for/related to terminal condition), this study compares hospice use (including the prevalence of later referrals) and sites of death for residents who did and did not receive Medicare SNF care in the last 90 days of life. Also, for residents with Medicare SNF care in the last 90 days of life, it examines the independent effect of hospice enrollment on the likelihood of a hospital death. This study focuses on perhaps the most vulnerable group of NH residents, those with advanced dementia, and includes the population of residents with advanced dementia who died in U.S. NHs in 2006.

Methods

Data and study population

A signed data use agreement from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was secured to use 2005–2006 NH resident assessment data (Minimum Data Set; MDS) for the 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, matched to Medicare Part A claims data (i.e., for hospice, hospital, home health, outpatient, and skilled nursing facility [SNF] care) and to Medicare enrollment data (which includes vital statistics data and information on health maintenance organization [HMO] enrollment). Residents enrolled in an HMO at any time in the last year of life were not included in this study because of the absence of Part-A Medicare SNF and hospital claims for these residents. Because this study's focus was on residents who had died, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

The above data were concatenated to create a Residential History File23 that was used to determine when and where NH residents died and the health care they received in the days and weeks prior to death. To this resident-level file we merged NH facility-level data obtained from the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) database and county-level data obtained from the Area Resource File (ARF).

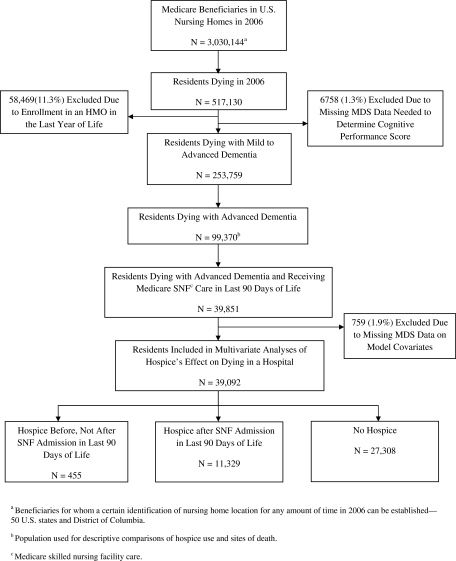

Residents were defined as having a NH death if their death occurred within one day of an identified NH stay or within seven days of hospital transfer from a NH (as done in previous research).8, 9 To identify residents who died with advanced dementia a diagnosis of “Alzheimer's” or “Dementia other than Alzheimer's” had to be documented on the MDS closest to death or on any Medicare Part-A claim (i.e., home health, hospice, hospital, outpatient, or SNF claim) in the last 12 months of life. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes we used to capture dementia have been used by others24,25 (290.xx, 291.2, 292.82, 294.1x, 294.8, 331.0-331.2, and 332.83). For residents with dementia diagnoses, the severity of dementia was determined using the cognitive performance scale (CPS) derived from the MDS closest to death.26,27 The CPS groups residents into seven cognitive performance categories based on five MDS items: 0=intact, 1=borderline intact, 2=mild impairment, 3=moderate impairment, 4=moderately severe impairment, 5=severe impairment, and 6=very severe impairment with eating problems. A CPS score of 5 corresponds to a mean Mini-Mental State Examination score of 5.1±(standard deviation [SD]) 5.3.26,27 Decedents with dementia diagnoses were defined as having advanced dementia if their CPS scores equaled 5 or 6 (n=99,370).26,27 Figure 1 shows the derivation of this population of residents.

FIG. 1.

Selection of study populations.

Variables of interest

Independent variables—SNF care and Medicare hospice

Medicare Part-A SNF claims were used to identify residents with SNF care in the last 90 days of life. NH hospice use was identified when dates on hospice claims overlapped with dates of NH stays, and hospice use “subsequent to SNF care” was identified when hospice occurred after an EoL SNF admission. Some infrequent overlap of hospice and SNF care was expected because dual access is allowed by Medicare policy when residents' diagnoses on their SNF claim(s) differ or are not related to the terminal diagnoses/conditions on the hospice claim(s).

Outcome variables

For comparisons of health care use by SNF/non-SNF residents we identified whether residents received NH hospice, had short hospice stays, and their sites of death. The residential history file was used to determine sites of death and hospice claims data were used to identify short hospice stays, which were defined as stays of 7 or fewer days. To examine the association between hospice enrollment and dying in a hospital we used the Residential History File to identify NH residents with SNF in the last 90 days of life and to determine whether deaths occurred in a hospital (i.e., had a hospital death within 7 days of NH transfer).

Control variables

We obtained resident demographic and social data from the resident's MDS, including age, gender, race, education, and marital status. Age was categorized as <75, 75–84 and 85+ years; race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other; education as less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and missing; and marital status as married versus other. We also captured the presence of selected symptoms and conditions including shortness of breath (yes/no), bedfast (yes/no), weight loss (10% of body weight; yes/no), congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, stroke, arteriosclerotic heart disease, renal failure, and other cardiovascular disease. To characterize functional impairment an activities of daily living (ADLs) scale, derived from the MDS and ranging from 0 to 28 (indicating lesser to greater impairment), was used.28 Also, we determined (using the MDS) whether decedents had do not resuscitate (DNR) or do not hospitalize (DNH) orders in place and if the NH documented end-stage disease on the MDS (defined as having 6 or fewer months to live). Finally, we identified decedents as having either short (≤90 days) or long (>90 days) NH lengths of stay because EoL health care utilization is known to be very different for these two resident groups.29

Nursing home- and county-level variables

We controlled for numerous NH-level variables, which were drawn from the OSCAR database. We included dichotomous variables to indicate if the NH was chain-affiliated or for-profit and if it had any special care unit or physician extenders. Continuous variables we controlled for included a NH's number of beds, occupancy rate, and its percentage of Medicaid and Medicare residents.

County-level attributes were identified using the ARF. We controlled for the number of hospital beds and the physicians per 100 individuals aged over 65 living in the county as well as for the level of NH competition within a county (by including the Herfindahl Iindex). We also controlled for the number of hospices providing care in NHs, and we used hospice (merged) claims for 2006 to determine these numbers.

Statistical analyses

Proportions and means were used to descriptively compare resident characteristics and outcomes. Although we used χ2, t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests in Table 1 to show statistical significance, these descriptive comparisons are not estimates because they are derived from the population of (non-HMO) NH residents dying with advanced dementia in 2006.

Table 1.

Hospice and Nonhospice Residents with Advanced Dementia and Medicare Skilled Nursing Facility Care in the Last 90 Days of Life (n=39,092)

| Variable | Hospice after SNF % or mean (SD) | No hospice after SNF % or mean (SD) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospice before Medicare skilled nursing facility care (not after) | – | 2 | – |

| Age categories | 0.061 | ||

| <75 (reference) | 10 | 9 | |

| 75–84 | 35 | 34 | |

| 85+ | 56 | 57 | |

| Male | 34 | 38 | 0.000 |

| Race categories | 0.002 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white (reference) | 84 | 83 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 12 | 12 | |

| Hispanic | 3 | 3 | |

| Other | 1 | 2 | |

| Education categories | 0.000 | ||

| Less than high school | 35 | 36 | |

| High school graduate (reference) | 44 | 41 | |

| At least some college | 18 | 15 | |

| Missing | 3 | 7 | |

| Married (versus other) | 28 | 30 | 0.000 |

| Advance directives | |||

| Do not resuscitate order | 77 | 73 | 0.000 |

| Do not hospitalize order | 11 | 10 | 0.286 |

| Cognitive Performance Scale of 6 (versus 5) | 68 | 70 | 0.000 |

| Activity of daily living impairments (1 unit increase) | 26(3) | 26(3) | |

| Shortness of breath | 23 | 26 | 0.000 |

| Bedfast | 32 | 34 | 0.000 |

| Weight loss (10% of body weight) | 36 | 31 | 0.000 |

| Diagnoses | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 26 | 28 | 0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 16 | 19 | 0.000 |

| Cancer | 8 | 5 | 0.000 |

| Stroke | 27 | 27 | 0.785 |

| Arteriosclerotic heart disease | 13 | 14 | 0.103 |

| Renal failure | 6 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 11 | 6 | 0.000 |

| Terminal diagnosis documented (on MDS) | 24 | 14 | 0.000 |

| Nursing stay of <90 days | 24 | 38 | 0.000 |

For the analytic analysis, we used logistic regression with generalized estimating equations to estimate the independent effects of hospice enrollment on the risk of dying in a hospital, using Version 11 of Stata software.30 The generalized estimating equation adjusted for the correlation occurring because of residents residing in the same NH. Also, we report relative risks because the estimates are based on population-based data.

Results

Forty percent of the 99,370 (non-HMO) NH residents dying with advanced dementia in 2006 had Medicare SNF care in the last 90 days of life. Thirty percent of residents with SNF care accessed hospice compared with 46% of residents without SNF care. Of residents with hospice, 40% of those with SNF care had hospice stays of 7 or fewer days, whereas only 19% of those without SNF care had these short hospice stays (data not shown).

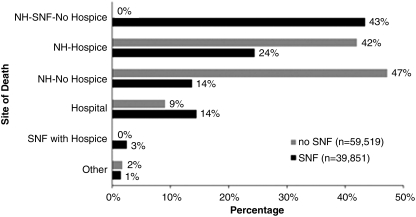

Sites of death varied dramatically by whether residents had Medicare SNF care in the last 90 days of life (Figure 2). Among residents with EoL Medicare SNF care, 14% died in a hospital, compared with 9% of residents without this SNF care. Three percent of residents died receiving Medicare hospice and SNF care simultaneously.

FIG. 2.

2006 sites of death for nursing home residents with advanced dementia and with and without SNF care (in last 90 days of life).

Table 1 compares residents with Medicare SNF care in the last 90 days of life who did or did not elect Medicare hospice. Although many differences between hospice and nonhospice residents were statistically significant, the absolute differences were often only modestly different. For example, 77% of hospice and 73% of nonhospice residents had DNR orders documented (p<0.001) and 11% of hospice and 10% of nonhospice residents had DNH orders (10%). Higher proportions of nonhospice residents had a CPS score of 6 (versus 5), shortness of breath, and were bedfast; a higher proportion of hospice (versus nonhospice) residents had weight loss (Table 1). CHF and COPD were more common for nonhospice residents and renal failure, cancer, and other cardiovascular disease more common for hospice residents. Of interest, only 24% of hospice residents had end-stage disease documented on their MDSs, whereas 14% of nonhospice residents had this documented.

Twenty percent of the SNF residents without hospice died in a hospital compared with 0.5% of those who elected hospice subsequent to SNF admission (data not shown). Controlling for numerous resident-, NH-, and county-level attributes, residents with Medicare SNF care (in the last 90 days of life) who received versus did not receive hospice had a 98% lower risk of dying in a hospital (95% CI: 0.014, 0.025; Table 2). Having advance directives was also associated with a resident's lower risk of dying in a hospital. Residents with DNR orders had a 67% lower risk of dying in a hospital (95% CI: 0.311, 0.357), and those with a DNH order had an 86% lower risk (95% CI: 0.111, 0.185). Residents documented as having end-stage disease had a 79% lower risk of a hospital death (95% CI: 0.171, 0.248). Being non-white or Hispanic, having a missing value for education, or having CHF, COPD, and stroke were all significantly associated with a higher risk of a hospital death. Being older or bedfast and having higher ADL impairment, dyspnea, weight loss, or cancer were all significantly associated with a lower risk of a hospital death (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression–Hospital Deaths for Residents with Advanced Dementia and Medicare SNF Care in the Last 90 Days of Life (n=39,092)¶

| Variable | Odds ratios (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Hospice before Medicare skilled nursing facility care (not after) | 1.06 (0.807, 1.400) |

| Hospice after Medicare skilled nursing facility care | 0.02 (0.014, 0.025)*** |

| Age categories | |

| <75 (reference) | |

| 75–84 | .85 (0.761, 0.954)** |

| 85+ | 0.72 (0.643, 0.805)*** |

| Male | 1.07 (0.998, 1.150) |

| Race categories | |

| Non-Hispanic white (reference) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.54 (1.400, 1.690)*** |

| Hispanic | 1.76 (1.495, 2.072)*** |

| Other | 1.36 (1.049, 1.767)* |

| Education categories | |

| Less than high school | 1.07 (0.996, 1.158) |

| High school graduate (reference) | |

| At least some college | 0.96 (0.873, 1.066) |

| Missing | 1.22 (1.074, 1.380)** |

| Married (versus other) | 1.03 (0.954, 1.111) |

| Advance directives | |

| Do not resuscitate order | 0.33 (0.311, 0.357)*** |

| Do not hospitalize order | 0.14 (0.111, 0.185)*** |

| Cognitive Performance Scale of 6 (versus 5) | 1.11 (1.004, 1.218)* |

| Activity of daily living impairments (1 unit increase) | 0.96 (0.944, 0.968)*** |

| Shortness of breath | 0.88 (0.813, 0.951)*** |

| Bedfast | 0.65 (0.604, 0.706)*** |

| Weight loss (10% of body weight) | 0.79 (0.740, 0.854)*** |

| Diagnoses | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.13 (1.052, 1.218)*** |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.11 (1.025, 1.209)* |

| Cancer | 0.82 (0.707, 0.944)** |

| Stroke | 1.13 (1.050, 1.213)*** |

| Arteriosclerotic heart disease | 1.02 (0.933, 1.125) |

| Renal failure | 0.84 (0.700, 1.012) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 0.95 (0.821, 1.093) |

| Terminal diagnosis documented (on MDS) | 0.21 (0.171, 0.248)*** |

| Nursing stay of <90 days | 1.07 (0.995, 1.144) |

Controlling for nursing home characteristics: profit status, chain status, percentage of residents on Medicaid, percentage of residents on Medicare, any special care unit, any physician extenders, total beds, occupancy rate; and for county characteristics: number of Medicare certified hospices, Herfindahl Index (i.e., nursing home competition), number of hospital beds, and number of physicians per persons 65+.

p≤.05; **p≤.01; ***p≤.001.

Discussion

NH residents with advanced dementia and with hospice enrollment subsequent to a Medicare SNF admission (in the last 90 days of life) had a dramatically reduced risk of a hospital death (compared with those without hospice). For this 2006 population of residents, only 0.5% of those with hospice died in a hospital compared with 20% without hospice. However, the rate of hospice enrollment was lower and the proportion of short hospice stays (≤7 days) was higher for the 40% of advanced dementia residents with SNF care. Our findings extend previous knowledge by showing the considerable differences in hospice use when residents receive versus do not receive Medicare SNF care near the EoL. Also, and importantly, for the very vulnerable population of NH residents dying with advanced dementia and receiving EoL Medicare SNF care, this study reports the powerful effect of subsequent hospice use in reducing the risk of a hospital death.

The Medicare policy disallowing simultaneous access to Medicare hospice and SNF care (when SNF care is for the terminal condition) has previously been cited as a major barrier to providing quality EoL care to persons with dementia in NHs,17 and others have recommended its dissolution.31,32 Our findings provide substantial support for these recommendations. The variations in hospice use between SNF and non-SNF residents raise a compelling concern regarding the quality of EoL care received by NH residents with advanced dementia; and, the low level of nonhospice palliative care and expertise in many U.S. NHs31,32 heightens this concern.

The substantially reduced risk of dying in a hospital for residents who access hospice subsequent to an EoL SNF admission provides support for the notion that dual access to SNF and hospice may reduce the rate of EoL hospitalizations. Like SNF care, Medicare hospice enrollees cannot access Medicare Part-A hospital care for conditions related to their terminal illnesses (and remain enrolled in hospice) and this policy undoubtedly contributes to the reduced risk of hospitalization. However, because hospice is responsible for the care coordination of NH hospice residents, most NHs have procedures in place to notify hospice regarding the potential need for hospitalization. Once notified, hospice staff intervenes in an attempt to prevent hospitalization. Similar routine intervention does not occur for many nonhospice residents who become acutely ill, or are actively dying.33,34 So, in addition to the palliative care expertise that accompanies hospice enrollment, care protocols associated with hospice enrollment appear to enable the avoidance of EoL hospitalization.

As in other studies,9,35 we found the presence of DNR and DNH orders to be associated with a much lower risk of a hospital death. Of interest, approximately three-fourths of SNF residents with and without hospice had DNR orders, whereas approximately 10% of each group had DNH orders (documented on the MDS). Whether or how residents or families were approached regarding their preferences is unknown, but the very low presence of DNH orders suggests a lack of discussions regarding resident/family preferences for hospital care and/or a lack of MDS documentation of these preferences. Furthermore, only 24% of hospice and 14% of nonhospice residents with advanced dementia had documented end-stage disease. Although determining a 6-month prognosis for residents with advanced dementia is difficult for clinicians across care settings,15,16 contributing to these very low proportions in NHs may be that nurses often lack the skills to recognize (less dramatic) signs of terminal decline.12,36 Considering this, incorporating systematic processes for assessing terminal decline into routine care planning could support staff in recognizing terminal decline and communicating with physicians about this decline.

Limitations

This study has limitations that deserve comment. First, the diagnosis of advanced dementia was determined indirectly using secondary data contained in MDS and Medicare claims. However, using our methodology, our NH dementia prevalence estimates were very similar to those from a Maryland study that used an expert panel and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DMS-III-R) criteria.37 Second, other resident-level demographic and clinical data were obtained from the MDS, and the possibility of inaccuracies must be considered. Additionally, this research describes hospice use by NH decedents with advanced dementia. We are unable to comment on the decision-making around hospice referral and on factors associated with referral other than those represented in our secondary data sources.

Conclusions

Results from this study suggest that NH residents' inability to simultaneously access Medicare Part A hospice and SNF care may be a barrier to hospice enrollment for NH residents with advanced dementia. It also supports the notion that dual access to Medicare hospice and SNF care may improve resident quality of life at the EoL by avoiding costly and potentially burdensome terminal hospital care. A “Medicare Hospice Concurrent Care Demonstration Program” is planned that will allow patients who are eligible for hospice to receive all other Medicare services simultaneously with hospice care.38 To gain a more thorough understanding of the benefits and costs of providing joint access to Medicare SNF and hospice care it is imperative that the NH population be included in this evaluation.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by the Alzheimer's Association (IIRG-08-91343), the Shaping Long Term Care in America Project funded by the National Institute on Aging (P01AG027296) and the National Institute on Aging (K24AG033640).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Mitchell SL. Teno JM. Miller SC. Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL. Kiely DK. Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):321–326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachs GA. Shega JW. Cox-Hayley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(10):1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell SL. Morris JN. Park PS. Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(6):808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volicer L. End-of-life care for people with dementia in residential care settings. 2005. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/endoflifelitreview.pdf. [Oct 29;2009 ]. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/endoflifelitreview.pdf

- 6.Mitchell SL. Teno JM. Kiely DK. Shaffer ML. Jones RN. Prigerson HG. Volicer L. Givens JL. Hamel MB. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teno JM. Mitchell SL. Gozalo PL. Dosa D. Hsu A. Intrator O. Mor V. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2010;303(6):544–550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller SC. Mor V. Wu N. Gozalo P. Lapane K. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gozalo P. Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baer WM. Hanson LC. Families' perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn JC. Dobbs D. Meier A. Williams CS. Biola H. Zimmerman S. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: Five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetle T. Teno J. Shield R. Welch LC. Miller SC. End of Life in Nursing Homes: Experiences, Policy Recommendations. Washington, D.C.: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL. Kiely DK. Miller SC. Connor SR. Spence C. Teno JM. Hospice care for patients with dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller SC. Lima JC. Mitchell SL. Hospice care for persons with dementia: The growth of access in US nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(8):666–673. doi: 10.1177/1533317510385809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell SL. Miller SC. Teno JM. Kiely DK. Davis RB. Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1929–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell SL. Miller SC. Teno JM. Davis RB. Shaffer ML. The advanced dementia prognostic tool: A risk score to estimate survival in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(5):639–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilly J. Fok A. Quality end of life care for individuals with dementia in assisted living, nursing homes, public policy barriers to delivering this care. 2007. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/End_interviewpaper_III.pdf. [Dec 8;2011 ]. http://www.alz.org/national/documents/End_interviewpaper_III.pdf

- 18.Centers for Medicareand Medicaid Services. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual., CMS Pub. 100-02, Chap. 8. http://www.cms.gov/Manuals/IOM/itemdetail.asp?itemID=CMS012673. [May 18;2011 ]. http://www.cms.gov/Manuals/IOM/itemdetail.asp?itemID=CMS012673

- 19.Magaziner J. Zimmerman S. Gruber-Baldini AL. van Doorn C. Hebel JR. German P. Burton L. Taler G. May C. Quinn CC. Port CL. Baumgarten M Epidemiology of Dementia in Nursing Homes Research Group. Mortality and adverse health events in newly admitted nursing home residents with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):1858–1866. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SC. Shield R. Mor V, et al. Palliative care/hospice for persons with terminal and/or chronic progressive illness: The role of state, federal policies in shaping access, quality for persons receiving long-term care. 2007. http://www.chcr.brown.edu/PDFS/JEHT_4_FINALREPORT07.PDF. [Dec 8;2011 ]. http://www.chcr.brown.edu/PDFS/JEHT_4_FINALREPORT07.PDF

- 21.Saliba D. Kington R. Buchanan J. Bell R. Wang M. Lee M. Herbst M. Lee D. Sur D. Rubenstein L. Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(2):154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy CR. Fish R. Kramer AM. Site of death in the hospital versus nursing home of Medicare skilled nursing facility residents admitted under Medicare's Part A Benefit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1247–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Intrator O. Berg K. Hiris V. Mor V. Miller S. Development and validation of the Medicare MDS Residential History File. Gerontologist. 2003;43:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt RJ. Sklar AR. Darkow T. Goldberg GA. Johnson JC. Harley CR. Prevalence of Parkinson's disease-induced psychosis in a large U.S. managed care population. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(1):105–110. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruber-Baldini AL. Stuart B. Zuckerman I. Simoni-Wastila L. Miller R. Effect Health Care Research Report Number 4. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Treatment of dementia among community-dwelling, institutional Medicare beneficiaries. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris JN. Fries BE. Mehr DR. Hawes C. Phillips C. Mor V. Lipsitz LA. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmaier SL. Sloane PD. Guess HA. Koch GG. Mitchell CM. Phillips CD. Validation of the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale: Agreement with the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Gerontol (A Biol Sci Med Sci). 1995;50(2):M128–M133. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.m128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris JN. Fries BE. Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol (A Biol Sci Med Sci). 1999;54:M546–M553. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller SC. Intrator O. Gozalo P. Roy J. Barber J. Mor V. Government expenditures at the end of life for short- and long-stay nursing home residents: Differences by hospice enrollment status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1284–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Sofware: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlson MD. Lim B. Meier DE. Strategies and innovative models for delivering palliative care in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier DE. Lim B. Carlson MD. Raising the standard: Palliative care in nursing homes. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):136–140. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks S. Warshaw G. Hasse L. Kues JR. The physician decision-making process in transferring nursing home patients to the hospital. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154(8):902–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayser Jones JS. Wiener CL. Barbaccia JC. Factors contributing to the hospitalization of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 1989;29(4):502–510. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lepore MJ. Miller SC. Gozalo P. Hospice use among urban black and white U.S. nursing home decedents in 2006. Gerontologist. 2011;51(2):251–260. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Welch LC. Miller SC. Martin EW. Nanda A. Referral and timing of referral to hospice care in nursing homes: The significant role of staff members. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):477–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruber-Baldini AL. Stuart B. Zuckerman IH. Hsu VD. Boockvar KS. Zimmerman S. Kittner S. Quinn CC. Hebel JR. May C. Magaziner J. Sensitivity of nursing home cost comparisons to method of dementia diagnosis ascertainment. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2009;2009:1–10. doi: 10.4061/2009/780720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Service CR. Medicare provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) 2010. [May 31;2011 ].