Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and biological effects of the gemcitabine/tanespimycin combination in patients with advanced ovarian and peritoneal cancer. To assess the effect of tanespimycin on tumor cells, levels of the chaperone proteins HSP90 and HSP70 were examined in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and paired tumor biopsy lysates.

Methods

Two-cohort phase II clinical trial. Patients were grouped according to prior gemcitabine therapy. All participants received tanespimycin 154 mg/m2 on days 1 and 9 of cycle 1 and days 2 and 9 of subsequent cycles. Patients also received gemcitabine 750 mg/m2 on day 8 of the first treatment cycle and days 1 and 8 of subsequent cycles.

Results

The tanespimycin/gemcitabine combination induced a partial response in 1 gemcitabine naïve patient and no partial responses in gemcitabine resistant patients. Stable disease was seen in 6 patients (2 gemcitabine naïve and 4 gemcitabine resistant). The most common toxicities were hematologic (anemia and neutropenia) as well as nausea and vomiting. Immunoblotting demonstrated limited upregulation of HSP70 but little or no change in levels of most client proteins in PBMC and paired tumor samples.

Conclusions

Although well tolerated, the tanespimycin/gemcitabine combination exhibited limited anticancer activity in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma, perhaps because of failure to significantly downregulate the client proteins at clinically achievable exposures.

Keywords: Phase I/II Trials, Tanespimycin, gemcitabine, ovarian cancer, peritoneal cancer, heat shock protein 90

Introduction

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is an evolutionarily conserved chaperone protein that promotes the folding of a diverse group of nascent polypeptides, which are known as “clients.” These clients include oncoproteins such as EGFR, Her2/neu, Akt, c-RAF, insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR) and others critical to signal transduction, transcription, cell proliferation and protein trafficking [1]. As a mediator of multiple essential cellular pathways, HSP90 is commonly overexpressed in tumor cells and is a rational target for drug development [2, 3]. The geldanamycin derivative tanespimycin (also known as 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin) binds to the HSP90 complex and inhibits its association with client proteins, resulting in their degradation [4, 5].

Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of phosphoinositide-3 (PI3) kinase/Akt pathway activation in the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer [6–8]. In addition, a number of cell surface receptors implicated in ovarian cancer, including Her2/neu and IGFR, also activate the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway [9]. Collectively, these changes are thought to contribute to the development of ovarian cancer and its chemoresistance. Importantly, Her2/neu, IGFR, and Akt are HSP90 clients.

Prior phase I and II studies of single agent tanespimycin in patients with advanced solid tumors have been performed. No complete or partial responses were reported but some patients were found to have prolonged stable disease [10–15].

Preclinical studies suggest that tanespimycin may sensitize tumor cells to some cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents [16]. Gemcitabine is a pyrimidine-based antimetabolite with activity against recurrent ovarian cancer [17, 18]. In the presence of certain types of DNA replication stress, the ATR/Chk1 signaling pathway promotes cell survival by stabilizing stalled replication forks and blocking additional origin firing [19]. Consistent with a role for Chk1 in protecting against gemcitabine toxicity, our previous work not only demonstrated that gemcitabine induces Chk1 activation in various cell lines, but also showed that inhibition of the ATR/Chk1 pathway by Chk1 siRNA or targeted deletion of various components of the pathway sensitizes tumor cells to gemcitabine [19, 20]. Additional studies identified Chk1 as a HSP90 client and demonstrated that tanespimycin exposure leads to Chk1 degradation, abrogating G1/S arrest induced by gemcitabine [21]. Treatment with the combination resulted in enhanced cytotoxicity compared to gemcitabine alone, particularly when tanespimycin exposure followed gemcitabine treatment.

A phase I clinical trial established that gemcitabine and tanespimycin can be safely given at the MTD of 750 mg/m2 and 154 mg/m2, respectively, on a weekly basis with some evidence of clinical activity in ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer [16]. Based on these data, we undertook a phase II trial of gemcitabine and tanespimycin in advanced ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma. The schedule utilized, gemcitabine followed a day later by tanespimycin, was chosen based on the efficacy of this sequence in preclinical studies [21]. We also investigated the effect of the regimen on the levels of HSP90 and HSP70 as well as the client proteins Her2, Akt, IGFR, InsR, c-Raf and Chk1 in PBMCs and paired tissue biopsies. The goal of this phase II study was to evaluate the efficacy and biological effects associated with gemcitabine and tanespimycin in patients with advanced ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer.

Patients and Methods

Women with relapsed or persistent epithelial ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma were eligible for this study if they met the following criteria: platinum resistance, defined as having evidence of disease that would be expected to be non-responsive to additional platinum-containing regimens due to progression while on or within six months of platinum therapy; contraindication to platinum-based chemotherapy; measurable or evaluable disease; or rising CA-125, even in the absence of other indicators of disease, if CA-125 is > 2x the UNL. Other eligibility criteria included age ≥ 18 years; WBC ≥ 3000 cells/mm3; platelets ≥ 100,000 cells/mm3; hemoglobin ≥ 9.0 g/dL; direct bilirubin < UNL; alkaline phosphatase ≤ 2.5 x UNL; AST ≤ 2.5 x UNL; creatinine ≤ 1.5 x UNL; and no prior exposure to gemcitabine (Cohort 1) or previous exposure to and disease progression while receiving gemcitabine (Cohort 2). If previous anthracycline therapy was administered, the ejection fraction had to be within the limits of normal. In addition, patients with accessible disease had to be willing to undergo tumor biopsies.

Exclusion criteria included the following: ECOG PS 3 or 4; uncontrolled infection; chemotherapy ≤ 4 weeks prior to enrollment; mitomycin C/nitrosoureas ≤ 6 weeks; immunotherapy ≤ 4 weeks; biologic therapy ≤ 4 weeks; radiation therapy ≤ 4 weeks; radiation to >25% of bone marrow; radiopharmaceuticals ≤ 4 weeks; failure to fully recover from acute, reversible effects of prior chemotherapy; significant cardiac disease; history of myocardial infarction ≤ one year; uncontrolled dysrhythmias or poorly controlled angina; CNS metastases or seizure disorder; use of other concurrent investigational research therapies; or history of serious allergic reaction to eggs.

Women who qualified for the study were divided into two groups according to their prior gemcitabine exposure. In order to evaluate whether tanespimycin would synergize with gemcitabine in gemcitabine naïve patients, Cohort 1 was comprised of patients who had no prior exposure to gemcitabine. Cohort 2 was designed to independently investigate whether tanespimysin could reverse gemcitabine resistance, and was comprised of patients with prior exposure to gemcitabine as a single agent or had experienced disease progression while on gemcitabine therapy, defined by increasing measurable disease or CA-125.

This study was approved by local institutional review boards; and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to registration.

Dosage and administration

Tanespimycin, supplied by the National Cancer Institute as a sterile single-use amber vial containing 50 mg of tanespimycin in 2 mL of dimethylsulfoxide, was diluted in egg phospholipid diluent as previously described and dispensed in glass bottles [16]. Vials of commercial gemcitabine were administered within 24 h of reconstitution.

Patients received 154 mg/m2 of tanespimycin intravenously over 2 hours on days 1 and 8 of the first treatment cycle and days 2 and 9 of subsequent cycles. In addition, patients received 750 mg/m2 of gemcitabine intravenously over 30 minutes on day 7 of the first treatment cycle and days 1 and 8 of subsequent cycles. Treatment cycles were 3 weeks in length.

Pharmacodynamic biomarkers

To assess the effect of tanespimycin on biomarkers, PBMCs were collected immediately prior to therapy on day 1 and at 22–26 hours after the start of infusion. Blood was collected in 4 CPT ™ tubes (Becton Dickinson), and centrifuged at 2,600 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. The lymphocyte and monocyte band was transferred, washed twice with PBS and spun at 1,200 rpm for 10 minutes each wash. The pellet was transferred to a microfuge tube and spun at maximum speed for 10 seconds. 4 volumes or a minimum of 100 μL of cold complete lysis buffer (10 mM TRIS, 0.1 mM EDTA pH 7.5, plus EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) was added, and samples were subsequently incubated on ice for 10 minutes. The samples were then stored at −80 degrees and/or shipped on dry ice. The levels of HSP70 and HSP90 as well as the client proteins Akt and c-Raf were assessed by gel electrophoresis and western blotting [10] with the antibodies described below.

In patients with accessible disease, paired core needle biopsies were obtained prior to treatment and on day 2, 22–26 hours after patients received tanespimycin intravenously as a 2-hour infusion. Biopsy samples were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored in liquid nitrogen. At the completion of the study, paired biopsies were sonicated in buffered 6 M guanidine hydrochloride under reducing conditions and processed for SDS-PAGE as described previously [22, 23]. Each gel with biopsy samples also contained a serial dilution of Ovcar5 whole cell lysate to serve as a standard curve. Samples were probed according to standard procedures [24] using the following antibodies: murine monoclonal anti-Chk1 and rabbit polyclonal anti-c-Raf (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt, Her2 and insulin receptor β-chain (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); murine monoclonal anti-HSP70 (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA); and murine monoclonal anti-HSP90β raised in the Mayo Antibody Core Facility. After detection of bound antibody using horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents, signals were scanned using an Epson 4870 scanner and quantified using ImageJ version 1.63 software. Signals were compared to the serially diluted Ovcar5 lysates probed on the same blots and normalized for Hsp90β content. A value of 1.0 indicates the same ratio for antigen to Hsp90β as Ovcar5 cells.

Statistical Methods

A one stage phase II study design with an interim analysis was used to assess efficacy within both study cohorts. The primary endpoint for both cohorts was the proportion of patients who experienced a confirmed response where confirmed response was defined using RECIST criteria and required an objective status of complete or partial response on two consecutive evaluations occurring four or more weeks apart. Secondary endpoints included overall survival, progression-free survival and clinical correlates as described in the previous section. Overall survival was defined as the time from registration to date of last follow-up or death due to any cause. Similarly, progression-free survival was defined as the time from registration to the date of progression or last follow-up, whichever came first. Duration of response was calculated at the date of study registration to the date of progression or last follow-up, whichever came first, in the subset of patients with confirmed response. Cohort 1 was designed with 90% power and 9.8% type I error rate to test the null hypothesis of a 10% response rate versus the alternative hypothesis of 30% response rate; six or more confirmed responses in 35 evaluable patients were required to show evidence for the alternative hypothesis, with two or more confirmed responses in the first 12 evaluable patients required at interim analysis in order to continue the full accrual. Cohort 2 was designed with 90% power and 9.4% type I error rate to test the null hypothesis of a 5% response rate versus the alternative hypothesis of a 20% response rate. Four or more responses in 37 evaluable patients were required to show evidence for the alternative hypothesis, with 1 or more of the first 12 evaluable patients required at interim analysis in order to continue the full accrual. Enrollment continued while waiting for interim analysis data to mature for both cohorts. A stopping rule was in place to suspend accrual if three or more of the first ten patients enrolled or 30% of all enrolled patients once accrual was greater than ten experienced a grade 3+ dyspnea, dehydration or anorexia event or grade 4+ adverse event considered at least likely to be related to treatment for each cohort. The number and severity of adverse events were tabulated and summarized within each cohort. Responses were summarized by simple descriptive statistics delineating complete and partial responses as well as stable and progressive disease within each cohort. The distributions of overall survival and progression free survival were estimated via Kaplan Meier methods.

Results

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled between November 15, 2007 and October 29, 2009. Patients were simultaneously accrued to both cohorts. Fifteen patients were enrolled to Cohort 1, one of whom was subsequently found to be ineligible. This cohort closed accrual after failing to meet interim analysis requirements. Fourteen patients were enrolled to Cohort 2, one of whom was found to be ineligible and two having major protocol violations. Cohort 2 closed early, due to drug-supply shortage at the NCI and lack of clinical activity, one patient short of the enrollment target. The patient characteristics for the 25 evaluable patients are presented by cohort in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Cohort 1 (n=14) | Cohort 2 (n=11) | Total (n=25) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median | 65.5 | 68 | |

| Range | (28–79) | (51–87) | |

| Age group | |||

| 18–48 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 50–59 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 60–69 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| ≥ 70 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 14 | 11 | 25 |

| Performance score | |||

| 0 | 12 | 4 | 16 |

| 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Primary site | |||

| Ovarian | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| Peritoneal | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Patients in Cohort 1 received a median of 3.5 cycles of treatment (range 1–14). All patients have discontinued study treatment. The reasons for discontinuing included disease progression (13 pts, 92.9%) and patient refusal (1 pt, 7.1%).

Patients in the Cohort 2 received a median of 4 cycles of treatment (range 1–10). All eleven eligible patients have discontinued study treatment, 10 (90.9%) because of disease progression and one (9.1%) for other reasons.

Response

Cohort 1

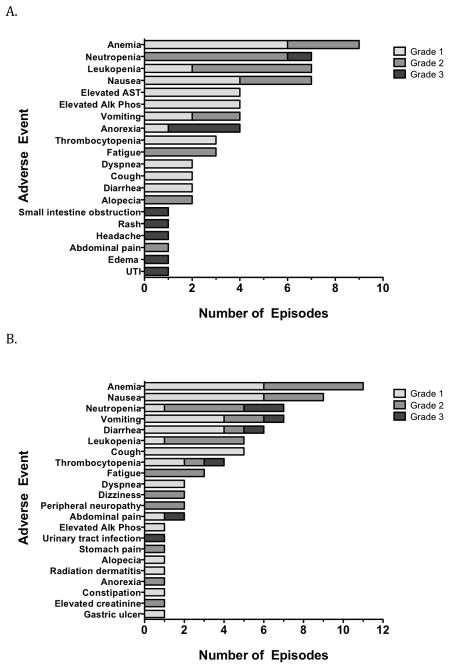

After the first 12 evaluable patients enrolled were observed for at least 4 cycles, an interim analysis identified one (8.3%) confirmed partial response, one (8.3%) stable disease, and 10 (83.4%) disease progressions (Table 3). The observed duration of response for the confirmed partial responder was 4.2 months, at which point the patient refused further treatment. The observed duration of stable disease for the one patient was 4.4 months. For the two patients not included in the interim analysis, one had stable disease for 7.1 months and the other had progressive disease. The patients were followed until death or a median of 30.1 months (range 29.2–31) among living patients. At last contact, 2 (17%) of the twelve eligible patients were still alive. Disease progression was observed in twelve (100%). The Kaplan-Meier overall survival median time was estimated to be 18.3 (95%CI; 6.2 NA) months and median time to progression was estimated to be 1.6 (95%CI: 1.2, 3.5) months as seen in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Best response on study in evaluable patients. The best antitumor response by RECIST criteria for each cohort. PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

| Best response | Cohort 1 (n=14) | Cohort 2 (n=11) | Total (n=25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| SD | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| PD | 11 | 7 | 18 |

Figure 1.

A, Overall survival of patients in Cohort 1 (N=12) and Cohort 2 (N=11) entered on this study. B, Progression-free survival of patients in Cohort 1 (N=12) and Cohort 2 (N=11) entered on this study.

Cohort 2

Due to NCI drug shortages, together with lack of activity resulting in trial closure, eleven patients were evaluable for interim analysis. Overall, four (36.4%) had stable disease observed for the median duration of 63 days (range: 42–140) and seven (63.6%) had disease progression (Table 3). Patients were followed until death. Disease progression was observed in eleven (100%). The Kaplan-Meier overall survival median time was estimated to be 11.5 (95%CI: 4.0, 13.7) months and median time to progression was estimated to be 2.7 (95%CI: 1.3, 5.1) months as seen in Figure 1.

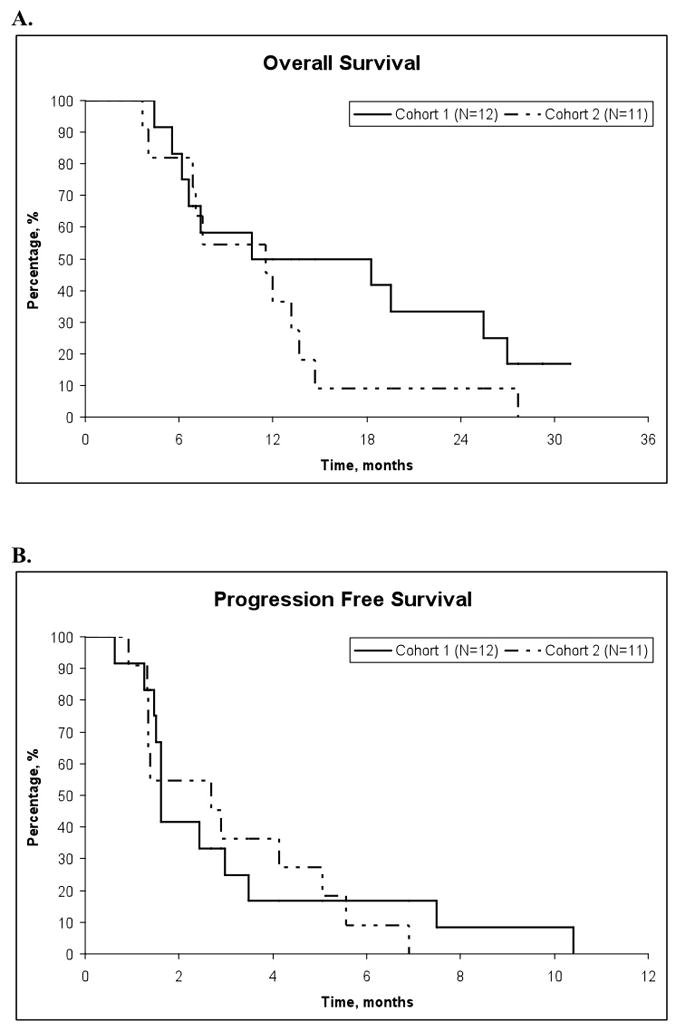

Adverse events

All patients were evaluated for adverse events as defined by the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 3.0 guidelines. Twenty- three patients were available for toxicity analysis. Adverse events at least possibly related to the treatment are depicted graphically in Figure 2. In Cohort 1 (Figure 2A), the most common adverse events were anemia (n=9), neutropenia (n=7), leukopenia (n=7), and nausea (n=7). In Cohort 2 (Figure 2B), the most common adverse events were anemia (n= 11), nausea (n=9), neutropenia (n=7), vomiting (n=7) and diarrhea (n=6).

Figure 2.

Maximum severity adverse events experienced per patient that were possible, probably or definitely related to treatment on this study.

Pharmacodynamic biomarkers

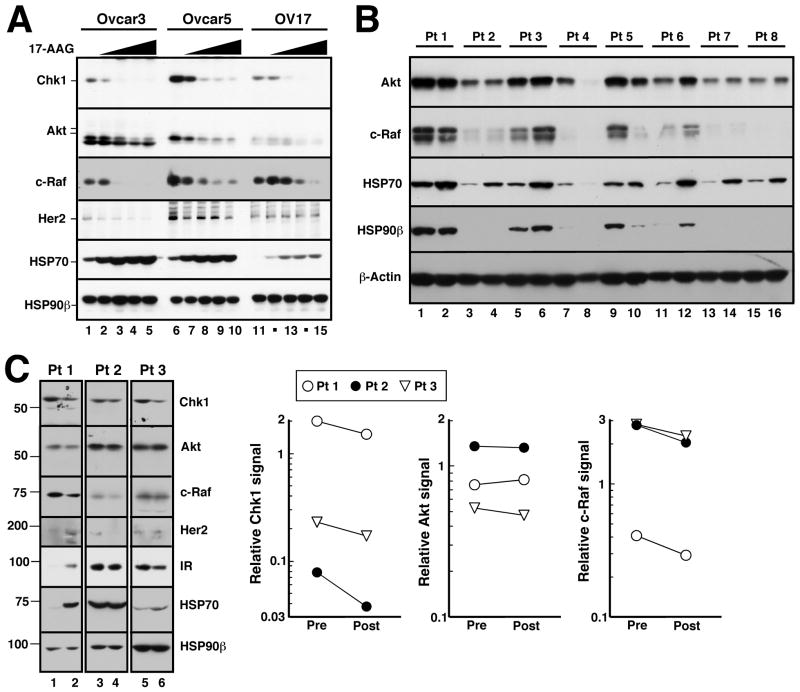

In order to assess the ability of tanespimycin to persistently disrupt the association of chaperone proteins and down-regulate client proteins, three ovarian cell lines were treated with tanespimycin for 24 hours with increasing concentrations varying from 30 nM to 1000 nM. As seen in Figure 3A, all three cell lines demonstrated dose-dependent HSP70 upregulation and stable levels of the constitutively expressed HSP90β. There were also dose-dependent reductions in levels of all client proteins evaluated, which were readily detectable at 30 nM, implicating tanespimycin-mediated destabilization of the HSP90 complex and subsequent degradation of the client proteins.

Figure 3.

Effects of tanespimycin on client protein levels. A, after the indicated ovarian cancer cell lines were treated with diluent (0.1% DMSO) or tanespimycin at 30, 100, 300, or 1000 nM for 24 h, whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting for the indicated antigen. B, lysates prepared from PBMCs prior to therapy (odd numbered lanes) and 24 h after the first dose of tanespimycin (even numbered lanes) were subjected to immunoblotting for the indicated antigens. HSP90β or β-actin served as loading controls in these studies. C, whole cell lysates prepared from ovarian cancer biopsies harvested prior to therapy (lanes 1, 3 and 5) or from the same tumors 22–26 h after the day 1 dose of tanespimycin (lanes 2, 4 and 6) were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Dashed line indicates remove of intervening unequally loaded samples from the blots. Number at left, migration of molecular weight markers (kDa). Graphs at right show quantitation of signals for selected client proteins before and after tanespimycin treatment.

As seen with the cell lines, PBMC HSP70 increased in six of the eight patients after tanespimycin exposure (Figure 3B). In contrast to the cell lines, there was limited, if any, destabilization of the client proteins examined, which included Akt and c-Raf.

Paired core tissue biopsies were obtained from three patients (two from Cohort 1; patient 1 and 3 in Figure 3C) and one from Cohort 2 (patient 2 in Figure 3C). In all three pairs, tanespimycin exposure led to a modest decrease in the client proteins. Densitometry was performed, and in comparison to the cell lines, the downregulation of the client proteins was limited, although there was a decrease in Chk1 expression in all three paired biopsies. Patient 2 had stable disease after four cycles, but progressed before cycle six. Patients 1 and 3 developed progressive disease after two cycles.

Discussion

HSP-90 directed therapy has been viewed as a means to simultaneously target several oncogenic signaling pathways and sensitize cells to chemotherapeutic agents. In vivo studies have shown that HSP-90 inhibitors lead to loss of Chk1 and a corresponding increase in gemcitabine-induced cancer cell death.

In the current trial, one partial response was seen on study in Group 1 and an additional six patients had stable disease, two from Group 1 and four from Cohort 2, as their best response. To date, there have been several trials evaluating combination therapy of tanespimycin with other agents, with limited clinical activity [25–27].

Biomarker studies performed in the present study provide a potential explanation for the limited activity of the gemcitabine/tanespimycin combination. Consistent with the minimal response rate seen in this study, there was limited downregulation of HSP90 client proteins. Interestingly, Chk1 was partially downregulated after tanespimycin in all three tumors that were serially sampled, consistent with preclinical data indicating that HSP90 inhibition leads to diminished Chk1 [21]. The level of downregulation with tanespimycin at this dose and regimen may not, however, have been adequate for a significant increase in gemcitabine sensitivity. Another possibility is that the decreased Chk1 levels result from the fact that that Chk1 is expressed predominantly during S phase and tanespimycin causes a G1 and G2 arrest [21, 28]. A variety of other client proteins, including Her2, IGF1R, IR, Akt and c-Raf, which are also susceptible to tanespimycin-induced downregulation in cell lines in vitro (Figure 3A), were not reliably downregulated by tanespimycin in situ (Figure 3C). This brings into question whether the dose of tanespimycin used in the trial was adequate to achieve the necessary exposure required for downregulation of the client proteins in tumor tissue.

Prior phase I studies have shown upregulation of HSP70 in PBMCs and tumor biopsies, which was seen in this study as well [10, 11, 13]. Data from Tillotson et al. have recently called into question the use of HSP70 as a predictor of HSP90 inhibitor-induced antitumor activity [29]. These authors have shown that response of xenografts to HSP90 inhibitors correlates with prolonged HSP90 occupancy, which is reflected in client protein downregulation. While HSP70 upregulation reflects release of HSF-1 from HSP90, HSP70 upregulation does not require the prolonged HSP90 occupancy and protein turnover required for downregulation of most client proteins. Moreover, HSP70 upregulation has been shown to protect cells from the cytotoxicity of tanespimycin [30]. Indeed, the heat shock response reflected in HSP70 upregulation may partially explain why the therapeutic benefit of single-agent tanespimycin has been limited despite its ability to affect the expression level of multiple proteins. In this combination study with gemcitabine, increasing HSP70 levels were not only seen in the PBMCs, but also in the paired tumor biopsies, as has been seen in other trials of HSP90 targeted therapies as well [10, 11, 13]. On the other hand, the minimal response of client proteins seen in the PBMCs may also be due to fact that HSP90 in normal tissues appears to be in a latent uncomplexed state that is less sensitive to HSP90 inhibitors than the HSP90 present in multi-chaperone complexes in tumor cells [31]. Unfortunately, despite the reported increased sensitivity of HSP90 in tumor tissue [31], the results from the paired biopsies showed only relatively small decreases in client protein expression.

In conclusion, although well tolerated, the tanespimycin/gemcitabine combination exhibited limited anticancer activity in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian and primary peritoneal carcinoma, perhaps because of failure to significantly downregulate important client proteins at clinically achievable exposures.

Table 2.

Dose administered during first 6 cycles of treatment by cohort

| Group | Cycle | No. of patients | 17- AAG | Gemcitabine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median total dose (mg) | Median dose administered (mg/m2) | % Receiving full dose | Median total dose (mg) | Median dose administered (mg/m2) | % Receiving full dose | |||

| Cohort 1 | ||||||||

| 1 | 14 | 544 | 154 | 100 | 1325 | 750 | 100 | |

| 2 | 13 | 502 | 154 | 92 | 2350 | 750 | 92 | |

| 3 | 8 | 286 | 154 | 88 | 1394 | 750 | 88 | |

| 4 | 7 | 360 | 154 | 100 | 2054 | 750 | 100 | |

| 5 | 3 | 572 | 154 | 100 | 2800 | 750 | 100 | |

| 6 | 3 | 370 | 154 | 100 | 2106 | 750 | 100 | |

| Cohort 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 11 | 554 | 154 | 100 | 1350 | 750 | 100 | |

| 2 | 10 | 486 | 154 | 100 | 2380 | 750 | 100 | |

| 3 | 6 | 485 | 154 | 83 | 2362 | 750 | 83 | |

| 4 | 6 | 403.5 | 154 | 100 | 1840 | 750 | 100 | |

| 5 | 4 | 500 | 154 | 100 | 2428 | 750 | 100 | |

| 6 | 4 | 388 | 154 | 100 | 2438 | 750 | 100 | |

Highlights.

Gemcitabine and tanespimycin combination therapy was well tolerated but had limited clinical activity.

Modest downregulation of Chk-1 was observed in clinical samples, but reliable downregulation of HSP90 or client proteins was not observed.

Based on clinical response and correlative studies, limited response is likely due to inadequate downregulation of HSP90 client proteins at therapeutically achievable concentrations.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Mayo Phase 2 contract N01-CM-62205

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Karen Flatten, Kevin Peterson and Paula Schneider with the correlative studies and Dr. David Toft, Ph.D., for his involvement in the development of the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–28. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitesell L, Lindquist SL. HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:761–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trepel J, Mollapour M, Giaccone G, Neckers L. Targeting the dynamic HSP90 complex in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:537–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnur RC, Corman ML, Gallaschun RJ, Cooper BA, Dee MF, Doty JL, Muzzi ML, Moyer JD, DiOrio CI, Barbacci EG, et al. Inhibition of the oncogene product p185erbB-2 in vitro and in vivo by geldanamycin and dihydrogeldanamycin derivatives. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3806–12. doi: 10.1021/jm00019a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte TW, Neckers LM. The benzoquinone ansamycin 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin binds to HSP90 and shares important biologic activities with geldanamycin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:273–9. doi: 10.1007/s002800050817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan ZQ, Sun M, Feldman RI, Wang G, Ma X, Jiang C, Coppola D, Nicosia SV, Cheng JQ. Frequent activation of AKT2 and induction of apoptosis by inhibition of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase/Akt pathway in human ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2000;19:2324–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao N, Flynn DC, Zhang Z, Zhong XS, Walker V, Liu KJ, Shi X, Jiang BH. G1 cell cycle progression and the expression of G1 cyclins are regulated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K1 signaling in human ovarian cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C281–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00422.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang HY, Zhang PN, Sun H. Aberration of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer and its implication in cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:81–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dam PA, Vergote IB, Lowe DG, Watson JV, van Damme P, van der Auwera JC, Shepherd JH. Expression of c-erbB-2, c-myc, and c-ras oncoproteins, insulin-like growth factor receptor I, and epidermal growth factor receptor in ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:914–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.10.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz MP, Toft D, Reid J, Ames M, Stensgard B, Safgren S, Adjei AA, Sloan J, Atherton P, Vasile V, Salazaar S, Adjei A, Croghan G, Erlichman C. Phase I trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1078–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerji U, O’Donnell A, Scurr M, Pacey S, Stapleton S, Asad Y, Simmons L, Maloney A, Raynaud F, Campbell M, Walton M, Lakhani S, Kaye S, Workman P, Judson I. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4152–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanathan RK, Trump DL, Eiseman JL, Belani CP, Agarwala SS, Zuhowski EG, Lan J, Potter DM, Ivy SP, Ramalingam S, Brufsky AM, Wong MK, Tutchko S, Egorin MJ. Phase I pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic study of 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17AAG, NSC 330507), a novel inhibitor of heat shock protein 90, in patients with refractory advanced cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3385–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowakowski GS, McCollum AK, Ames MM, Mandrekar SJ, Reid JM, Adjei AA, Toft DO, Safgren SL, Erlichman C. A phase I trial of twice-weekly 17-allylamino-demethoxy-geldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6087–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanathan RK, Egorin MJ, Eiseman JL, Ramalingam S, Friedland D, Agarwala SS, Ivy SP, Potter DM, Chatta G, Zuhowski EG, Stoller RG, Naret C, Guo J, Belani CP. Phase I and pharmacodynamic study of 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in adult patients with refractory advanced cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1769–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solit DB, Ivy SP, Kopil C, Sikorski R, Morris MJ, Slovin SF, Kelly WK, DeLaCruz A, Curley T, Heller G, Larson S, Schwartz L, Egorin MJ, Rosen N, Scher HI. Phase I trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1775–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubbard J, Erlichman C, Toft DO, Qin R, Stensgard BA, Felten S, Ten Eyck C, Batzel G, Ivy SP, Haluska P. Phase I study of 17-allylamino-17 demethoxygeldanamycin, gemcitabine and/or cisplatin in patients with refractory solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9381-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markman M, Webster K, Zanotti K, Kulp B, Peterson G, Belinson J. Phase 2 trial of single-agent gemcitabine in platinum-paclitaxel refractory ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:593–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowler WC, Jr, Van Le L. Gemcitabine as a single-agent treatment for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:S21–3. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connell MJ, Cimprich KA. G2 damage checkpoints: what is the turn-on? J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karnitz LM, Flatten KS, Wagner JM, Loegering D, Hackbarth JS, Arlander SJ, Vroman BT, Thomas MB, Baek YU, Hopkins KM, Lieberman HB, Chen J, Cliby WA, Kaufmann SH. Gemcitabine-induced activation of checkpoint signaling pathways that affect tumor cell survival. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1636–44. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arlander SJ, Eapen AK, Vroman BT, McDonald RJ, Toft DO, Karnitz LM. Hsp90 inhibition depletes Chk1 and sensitizes tumor cells to replication stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52572–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman HS, Dolan ME, Kaufmann SH, Colvin OM, Griffith OW, Moschel RC, Schold SC, Bigner DD, Ali-Osman F. Elevated DNA polymerase alpha, DNA polymerase beta, and DNA topoisomerase II in a melphalan-resistant rhabdomyosarcoma xenograft that is cross-resistant to nitrosoureas and topotecan. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3487–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann SH, Svingen PA, Gore SD, Armstrong DK, Cheng YC, Rowinsky EK. Altered formation of topotecan-stabilized topoisomerase I-DNA adducts in human leukemia cells. Blood. 1997;89:2098–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann SH. Reutilization of immunoblots after chemiluminescent detection. Anal Biochem. 2001;296:283–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tse AN, Klimstra DS, Gonen M, Shah M, Sheikh T, Sikorski R, Carvajal R, Mui J, Tipian C, O’Reilly E, Chung K, Maki R, Lefkowitz R, Brown K, Manova-Todorova K, Wu N, Egorin MJ, Kelsen D, Schwartz GK. A phase 1 dose-escalation study of irinotecan in combination with 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6704–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson PG, Badros AZ, Jagannath S, Tarantolo S, Wolf JL, Albitar M, Berman D, Messina M, Anderson KC. Tanespimycin with bortezomib: activity in relapsed/refractory patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:428–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaishampayan UN, Burger AM, Sausville EA, Heilbrun LK, Li J, Horiba MN, Egorin MJ, Ivy P, Pacey S, Lorusso PM. Safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the combination of sorafenib and tanespimycin. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3795–804. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesa RA, Loegering D, Powell HL, Flatten K, Arlander SJ, Dai NT, Heldebrant MP, Vroman BT, Smith BD, Karp JE, Eyck CJ, Erlichman C, Kaufmann SH, Karnitz LM. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition sensitizes acute myelogenous leukemia cells to cytarabine. Blood. 2005;106:318–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tillotson B, Slocum K, Coco J, Whitebread N, Thomas B, West KA, MacDougall J, Ge J, Ali JA, Palombella VJ, Normant E, Adams J, Fritz CC. Hsp90 (heat shock protein 90) inhibitor occupancy is a direct determinant of client protein degradation and tumor growth arrest in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39835–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCollum AK, Lukasiewicz KB, Teneyck CJ, Lingle WL, Toft DO, Erlichman C. Cisplatin abrogates the geldanamycin-induced heat shock response. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3256–64. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamal A, Thao L, Sensintaffar J, Zhang L, Boehm MF, Fritz LC, Burrows FJ. A high-affinity conformation of Hsp90 confers tumour selectivity on Hsp90 inhibitors. Nature. 2003;425:407–10. doi: 10.1038/nature01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]