Abstract

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and long-term disability in the U.S. Currently, surgical intervention decisions in asymptomatic patients are based upon the degree of carotid artery stenosis. While there is a clear benefit of endarterectomy for patients with severe (>70%) stenosis, in those with high/moderate (50–69%) stenosis the evidence is less clear. Evidence suggests ischemic stroke is associated less with calcified and fibrous plaques than with those containing softer tissue, especially when this it is accompanied by a thin fibrous cap. A reliable mechanism for the identification of individuals with atherosclerotic plaques which confer the highest risk for stroke is fundamental to the selection of patients for vascular interventions.

Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) imaging is a new ultrasonic-based imaging method that characterizes the mechanical properties of tissue by measuring displacement resulting from applied short duration acoustic radiation force. These displacements provide information about the local mechanical properties of tissue and can differentiate between soft and hard areas. Because arterial walls, soft tissue, atheromas, and calcifications have a wide range in their stiffness properties, they represent excellent candidates for ARFI imaging.

We present information from early phantom experiments and excised human limb studies to in vivo carotid artery scans and provide evidence for the ability of ARFI to provide high quality images which highlight mechanical differences in tissue stiffness not readily apparent in matched B-mode images. This allows ARFI to identify soft from hard plaques and differentiate characteristics associated with plaque vulnerability or stability.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Carotid Artery Disease, Carotid Stenosis, Endarterectomy Carotid, Imaging Diagnostic, Ultrasonography, Stroke

Introduction

Approximately 700,000 people in the United States suffered new strokes in 2007. Stroke is the third leading cause of death (160,000 per year) and serious, long-term disability in the U.S. The economic impact of this disease is enormous, with over 3.8 billion dollars paid each year to Medicare beneficiaries1. Although estimates vary, approximately 20–30% of new strokes each year are due to atherosclerotic carotid artery disease2. Currently, surgical intervention decisions in asymptomatic patients are based upon the degree of stenosis. In three major clinical trials, the North American Symptomatic Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET)3, the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST)4, and the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Trial (ACAS)5, the benefit of carotid endarterectomy in stroke prevention for patients with severe (>70%) carotid artery stenosis was clearly demonstrated. However, in patients with high/moderate (50–69%) stenosis even with previous symptoms of focal cerebral ischemia the evidence is less clear6, 7.

A a reliable mechanism for the identification of individuals with atherosclerotic plaques which confer the highest risk for stroke is fundamental to the selection of patients for vascular intervention8. It is likely that tens of thousands of patients each year could be spared from undergoing carotid endarterectomy if their plaques could be identified as stable. Conversely, individuals with high/moderate stenosis and vulnerable plaques that may be good candidates for intervention could be identified earlier.

Evidence suggests ischemic stroke is associated less with calcified and fibrous plaques than with those containing softer tissue9, 10. The soft tissue in atherosclerotic plaque can consist of lipid pools, macrophages, foam cells, debris from intra-plaque hemorrhage, as well as numerous other tissues due to the response of the immune system. The soft tissue is often surrounded by a fibrous cap, which is prone to rupture if the cap is thin. The definition of a vulnerable plaque remains somewhat unclear, however, as the cap thickness defining vulnerability varies in the literature from 65 μm11, 12 to up to 700 μm13, 14.

A recent trend in imaging atherosclerotic plaques has been to ascertain the vulnerability of a plaque to rupture via imaging characteristics or imaging the mechanical properties of the plaque. B-mode ultrasonography typically defines plaques as hypoechoic or hyperechoic, and homogeneous or heterogeneous15–17 using a subjective grey-scale classification. Hypoechoic and heterogeneous plaques appear to be related to ipsilateral neurologic events15, 16, but consistency between institutions and the reproducibility of the plaque characterization is relatively poor18. Coronary artery plaques are relatively well identified via intravascular optical coherence tomography (OCT)19 and intravascular ultrasound elastography20, 21. However, these techniques are invasive and may have difficulty in distinguishing carotid artery plaque vulnerability22. Finally, magnetic resonance imaging is a modality which can be very sensitive to plaque composition23–25, but may be prohibitively expensive for widespread use.

Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) imaging is a new method that we have developed over the past decade. ARFI imaging is an ultrasonic-based imaging method that uses short duration (.03–1 ms) acoustic radiation force to generate localized displacements in tissue 26–30. These displacements provide information about the local mechanical properties of tissue because the displacement and recovery of tissue is inversely related to tissue stiffness and its viscoelastic properties. Because arterial walls, soft tissue, atheromas, and calcifications have a wide range of stiffness properties, they represent excellent candidates for ARFI imaging.

The aim of this paper is to review and summarize the current status and future potential of ARFI imaging for the generation of high-resolution images of carotid plaque composition. We present a range of information (some previously published in technical journals) on early phantom experiments to distinguish layers and occlusions of different modulus, including compliant occlusions mimicking a soft lipid-pool plaque. We also report our recent ex vivo and in vivo studies designed to assess the ability of ARFI imaging to detect and characterize the mechanical properties of atherosclerotic plaques and correlate ARFI-derived plaque measurements with those obtained via B-mode and angiographic images, and with those derived from pathology and direct mechanical measurements.

Methods

ARFI Imaging

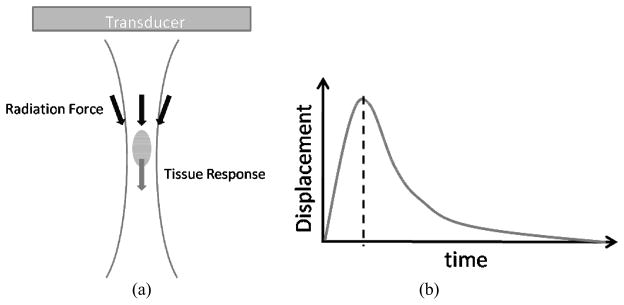

ARFI imaging is designed to work on a diagnostic ultrasound scanner, using a single transducer to both generate the radiation force and track the resulting displacement of tissue. Radiation force is generated when an acoustical pulse is absorbed by tissue, creating a transfer of momentum in the insonified region (Figure 1). Because scattering can generally be neglected in this model 31, 32, and assuming plane-wave propagation of the acoustic wave, the radiation force applied to tissue can be described by 33–36:

where F is the acoustic radiation force, I is the time-averaged intensity of the acoustic pulse, c is the speed of sound in the medium, and α is the attenuation coefficient of the tissue.

Figure 1. a–b. The mechanism of ARFI radiation force imaging pulse.

(a) Schematic representation of the radiation force field generated by an ARFI imaging pulse. The radiation force is generated within the shape of the transmitted ultrasound beam, approximated by the two curved lines, with the maximum force typically observed at the focal point of the beam. (b) A typical response of the tissue to the radiation force impulse. The tissue at the focal point displaces away from the transducer momentarily and then recovers back to its original position. ARFI images are often created at the point of peak tissue displacement, shown by the dotted line.

In order to achieve appreciable displacement in tissue (i.e. ten microns), the intensity of the acoustic wave must be increased roughly two orders of magnitude above that used for diagnostic imaging. Displacement of tissue immediately after force application is inversely related to local tissue stiffness (i.e. softer tissues displace farther that stiffer tissues for the same force magnitude). Additionally, all tissues are inherently viscoelastic, and differences in the recovery rates of tissues are related to their elastic, damping, inertial, and structural properties.

A current limitation with ARFI imaging is that the actual force is often unknown because the acoustic intensity and attenuation coefficient are usually not known. Therefore, observations of tissue stiffness are made relative to neighboring or nearby objects and tissue in a typical 2-D ARFI image.

Implementation of ARFI imaging is quite different than conventional B-mode and color Doppler imaging. To obtain displacement information for one spatial location (or one vertical line in an image) a reference line is first acquired. The reference line is obtained using conventional ultrasound. The reference line is then followed with a radiation-force inducing pulse at the same location. This force-generating pulse is also referred to as a pushing pulse because it “pushes” on the tissue to create a small displacement. The pushing pulses used in ARFI imaging of the carotid artery are often 24 to 59 μs in duration, depending on the depths of arterial walls.

Following the pushing pulse, a series of tracking lines are acquired, which are identical to the reference line, in order to observe the response of the tissue to the radiation force. These lines are called tracking lines because they are used to track the displacement of the tissue as it moves away from and recovers to its original position. Techniques such as cross-correlation or phase-shift estimation are often used to compare the tracking lines to the reference line to estimate how far the tissue has moved. In general, approximately 4–6 ms of tracking is required to observe the recovery of the tissue back to its original location, and the accuracy of these estimation techniques is on the order of tenths of microns. By repeating the reference-push-track sequence over several spatial locations, a two-dimensional image can be created by aligning the displacements of each location in time, relative to its pushing pulse.

One concern with ARFI imaging is that the pushing pulses have the capability to generate more heat than conventional ultrasound, both within the tissue and the transducer, but particularly on the surface of the transducer. Therefore, the imaging sequences must be designed to minimize heating of both the tissue and transducer. While there are many factors that affect heating, techniques such as parallel tracking can be used to decrease both tissue and transducer heating 37. All ARFI imaging methods used in this study have been created to comply with the temperature limits set by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 38.

Phantom Construction and Imaging

Tissue-mimicking vascular phantoms were constructed to evaluate ARFI’s ability to discriminate a softer material (representing a potential lipid-pool, thrombotic-prone plaque) from a stiffer vascular wall. All phantoms were made using polyvinyl-alcohol cryogel (PVA-C), a material that has shown to be well suited for vascular modeling in MRI and ultrasound applications 39–42. PVA-C rigidity is determined by the number of freeze-thaw cycles and the thaw rate. One normal and two stenotic vessel phantoms were created as described previously43. The compliant plaques within the stenotic vessels had occlusions of approximately 44% and 80% of the vessel area. The Young’s modulus of the vessel material was estimated to be 119 kPa, and the Young’s modulus of the occlusion material was estimated to be 19 kPa. The normal phantom was deposited into a gelatin and graphite mix of approximately 20 kPa, and the stenotic vessels were placed in a saline bath.

The phantoms were mounted in a closed-loop pressure system, pressurized to 10 kPa, and imaged using conventional B-mode and ARFI imaging. A mechanical translation stage was used to scan the vessel phantoms. Transverse B-mode and ARFI images were recorded along the length of each of the vessels.

Excised Human Limb Studies

In an effort to compare pathological results with mechanical properties derived from ARFI imaging in human vessels and vascular disease, we have previously applied ARFI imaging to excised popliteal and femoral arteries from patients undergoing leg amputation44. These patients often had some form of peripheral vascular disease related to diabetes, and therefore the excised vessels often contained large and occluding plaques. The vessels were placed in a water tank with their ends loosely suspended from two opposing cannulas. Using the same mechanical translation stage as used with the phantoms, the vessels were scanned with B-mode and ARFI imaging. Pathology of the vessels was obtained after scanning to compare the ARFI imaging results with the diseased and healthy portions of the vessel.

Human in vivo studies

Using the guidelines for noninvasive laboratory testing report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society for Vascular Medicine45 we recruited volunteers with 50–69% internal carotid artery disease. Classification under this criteria includes any of; a) internal carotid artery peak systolic velocity of 125–230cm/sec; b) internal carotid artery end diastolic volume of 40–100cm/sec; c) internal carotid artery/common carotid artery peak systolic volume ratio of 2–4 or; d) measured plaque volume estimate of >50%. All volunteers were recruited under an Institutional Review Board approved protocol, and informed consent was obtained for each volunteer prior to imaging. Healthy control subjects were selected who had no risk factors for cardiovascular disease and subsequently yielded non-stenotic carotid scans. All B-mode and ARFI scans of the carotid arteries were performed at the Frederick R. Cobb Non-Invasive Vascular Research Laboratory at the Duke Center for Living Campus.

ARFI imaging was implemented on a modified Siemens Acuson S2000™ scanner and a 9L4 transducer (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Issaquah, WA), and the resulting in-phase and quadrature data was acquired and ported to local workstations to calculate displacement images of the carotid vasculature. For each ARFI image acquired, a B-mode and color Doppler image were acquired concurrently. For each plaque observed in a volunteer, between two and five ARFI images were acquired to assess repeatability of the image. Each image was acquired a few seconds apart in order to confirm the repeatability of the results. Images were created from the displacements measured 0.43 ms after the application of radiation force.

A digital mask was applied to the lumen of the vessels in the ARFI images in order to improve the visibility of the vascular walls and plaque. The continuous movement of blood appears to the displacement estimator as high spatially-variant displacements and makes visualization of the image difficult. Therefore, the mask is applied by computing the power of the Doppler signal and setting the corresponding regions of the ARFI image with power greater than 5–10% of the maximum power to black.

Results

Phantom Scanning

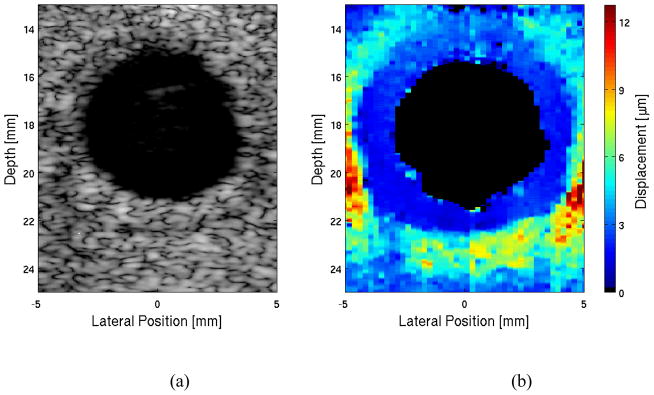

Transverse B-mode and ARFI images of a normal vessel phantom, made to represent a non-diseased artery, and embedded in the graphite and gelatin medium are shown in figure 2. In the ARFI image, small displacements are shown in dark blue, while relatively larger displacements are shown in red. While there appears to be little difference between the vessel wall and the embedding material in the B-mode image, the ARFI image shows high contrast (approximately 4:1) between two media. The border of the vessel is well defined, and the vessel phantom shows uniform displacements throughout the vessel wall.

Figure 2. a–b. Matched (a) B-mode and (b) ARFI transverse images of a vessel phantom embedded in a gelatin/graphite mix.

There is little difference between the vessel phantom and the background in the B-mode image. In the ARFI image, dark blue corresponds to low displacement and red corresponds to high displacement. There is high contrast between the vessel phantom and the background in the ARFI image compared to the B-mode image. Because the vessel phantom displaces significantly less than the background, the vessel phantom is stiffer than the surrounding medium.

Figure 3 displays matched transverse B-mode and ARFI scans of the occluded vessel phantoms. In figures 3(a) and 3(b), B-mode and ARFI images of the 44% occluded vessel phantom are shown. The area associated with the vessel wall is displacing 4.0 ± 0.6 μm and is indicated by the dark blue color in the ARFI image, while the green region depicting the plaque is displacing 12.0 ± 2.4 μm. The occlusion area is homogeneous with the vessel wall in the B-mode image. In figures 3(c) and 3(d), B-mode and ARFI images of the 80% stenotic vessel phantom are shown. The vessel wall displaces 3.3 ± 1.2 μm and the plaque displaces 10.4 ± 2.1 μm in the ARFI image. Like the 44% occlusion phantom, the B-mode image of the 80% occlusion phantom shows indistinguishable contrast between the soft plaque and the harder vessel wall.

Figure 3. a–d. Matched B-Mode (a & c) and ARFI (b & d) images of vessel phantoms with 44% (a & b) and 80% (c & d) soft occlusions.

The vessel is indistinguishable from the occlusion in the B-mode images, however the ARFI images display the difference between the stiffer vessel wall and softer occlusion with good contrast

Excised Human Limb Studies

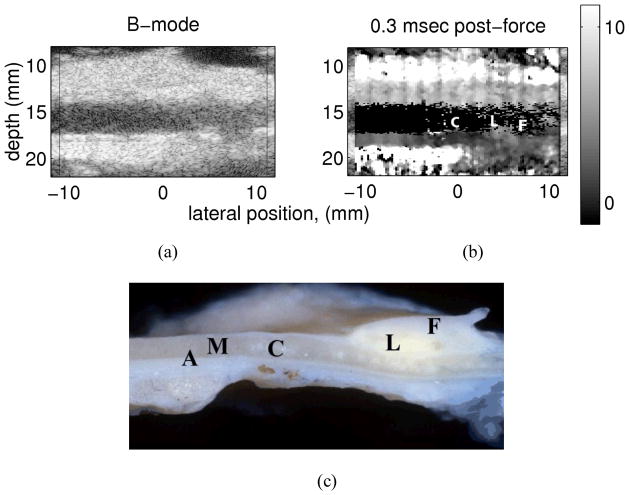

The ARFI images of excised vessels in our previous studies distinguished characteristics of healthy vessel, calcified regions, and a soft, lipid-filled core44. Figure 4 shows the matched B-mode and ARFI images from one of these excised vessels displaying a plaque with a lipid core. The distinguishing characteristics were largely found in ARFI-derived parametric images, such as the maximum observed displacement over time, the time to reach peak displacement, and the recovery time of the tissue. Lipid-filled regions were consistent with large displacements, slow times to reach peak displacement, and a slow recovery time. Calcified regions were consistent with low displacements and quicker times to reach peak displacement and recovery times. Healthy vessel wall lay between the calcified and lipid-filled regions in terms of maximum displacement, time-to-peak, and recovery time. Although the elastic moduli of these tissues could not be known precisely, the measured mechanical response for the tissues observed in the excised vessel were consistent with the Young’s modulus of these tissues reported in the literature 46–49. Typically, lipid-filled regions are on the order of 1/100 the modulus of normal arterial tissue, and fibrous and calcified plaques have moduli that are orders of magnitude greater than normal arterial tissue.

Figure 4. a–c Matched (a) B-Mode and (b) ARFI images from an excised popliteal artery shown in photograph (c).

The photograph of the excised vessel and plaque shows areas of healthy vessel (A & M), calcifications (C) lipid core (L) and a fibrous cap (F) on the distal wall. The ARFI image depicts very low displacement in the location of the calcifications (the dark area beneath the label C) and larger displacement in the region of the lipid core (labeled L). Reprinted with permission from 44 .

Human in vivo Carotid Scanning

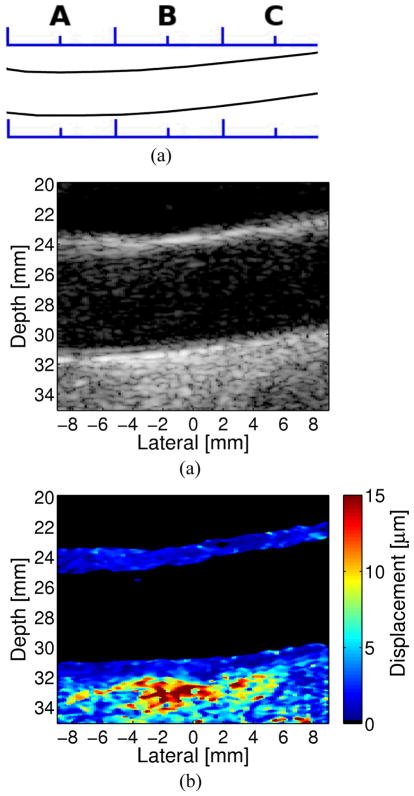

Two-dimensional ARFI images accompanied by traditional B-mode images of human carotid arteries scanned in vivo are shown in figures 5–7. Figure 5 displays the matched B-mode and ARFI images from the left common carotid artery of a healthy 39-year-old male. Uniform displacements are observed across the vessel length (displacements are approximately 2 μm in both the distal and proximal walls). Differences in mean displacement can occur between the proximal and distal walls, however. This is largely due to focal and absorption effects of the radiation force and the relative position of the wall to the region of excitation. Because the possibility of these differences occurring, interpretation of the stiffness of objects in ARFI images should be limited to the displacement of the target relative to nearby or adjacent regions.

Figure 5. a–c An Example of a Healthy Carotid Vessel.

(a) Longitudinal sketch of the common carotid artery in the subject. Matched (b) B-Mode and (c) ARFI images from location B the CCA in a healthy 39-year-old male. The ARFI images indicate that healthy vascular tissue shows homogeneous stiffness throughout the vessel.

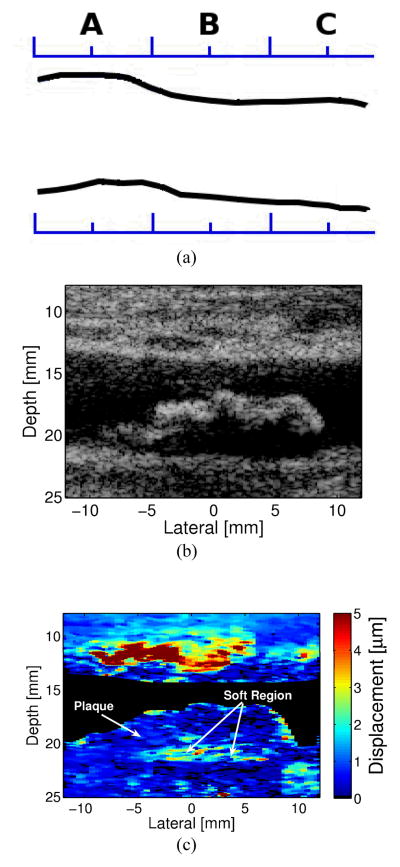

Figure 7. An Example of a Carotid Artery Containing an Intermediate Soft Plaque.

(a) Longitudinal sketch of the common carotid artery of the subject. Matched longitudinal (b) B-Mode and (c) ARFI images from the CCA and plaque located in the region of B.

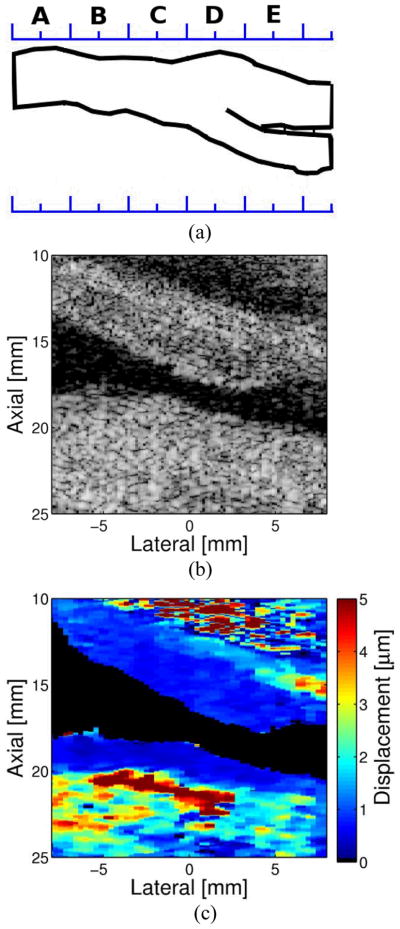

Figure 6 shows the matched B-mode and ARFI images from the left internal carotid artery of a 57-year-old male. The plaque is visible on both the proximal and distal wall, as it appears to wrap around the vessel. The accompanying ARFI image shows uniform stiffness throughout the plaque suggesting fibrous and/or calcific composition. Note that the plaque cannot be distinguished from the vessel wall.

Figure 6. An Example of a Carotid Artery Containing a Homogeneously Hard Plaque.

A (a) Longitudinal sketch of the carotid artery in the subject. Matched (b) B-Mode and (c) ARFI images from the ICA and plaque in the vicinity of location E. The ARFI images here indicate that this plaque (shown in dark blue) is homogenously stiff.

Figure 7 displays matched B-mode and ARFI images from the right common carotid artery of a 68-year-old male. The B-mode image indicates a bright border with a possible echolucent core. ARFI imaging reveals a heterogeneous composition of stiffness, consisting of a soft region (a possible lipid core) surrounded by a large stiff or fibrous cap. The soft region of the plaque is visible on the distal wall as the region extending from −5 to 7 mm laterally and from 19 to 22 mm in depth in the ARFI image. The soft region is surrounded by a significantly stiffer region. The displacement of the soft region ranges from 2–4 μm, compared to 0.5–1 μm in the surrounding stiffer tissue. Although the tissue surrounding the soft region appears thick in this image, the size of the soft region, assuming it is a lipid core, fits the criteria used by Ge et al. (1999) to determine plaque vulnerability14. This definition of vulnerability includes any of the following criteria: 1) a lipid core with area greater than 1 mm2; 2) a core to plaque ratio greater than 20%: or 3) a fibrous cap less than 0.7 mm thick. The soft region in this plaque is greater than 1 mm2 and it covers a region of the plaque greater than 20% of the total area. Note that the apparent soft regions around the edge of the plaque are the vessel lumen where the Doppler mask did not cover the entirety of the lumen.

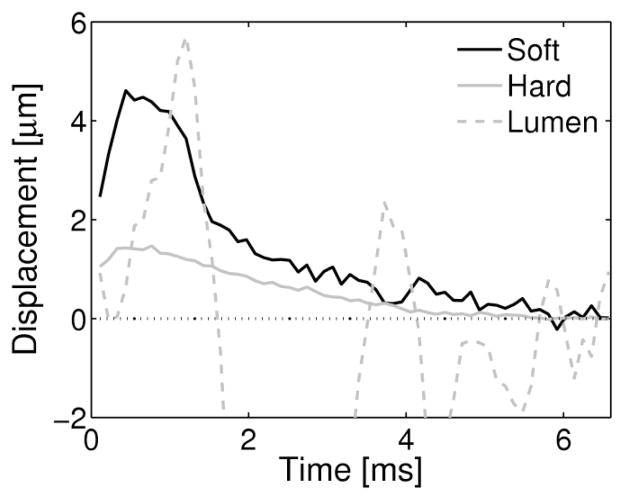

The soft region depicted in figure 7 can be easily differentiated from noise or image artifacts, such as the apparent large displacements observed in the lumen that would signify a soft region. Figure 8 shows the response of the plaque in figure 7 to the applied radiation force compared to the response measured from the lumen. In the soft and hard regions of the plaque, the tissue displaces away from the transducer and recovers back to its original position, with the soft region displacing approximately 3 times greater at its peak displacement than the hard region of the plaque. The displacements observed from a region within the lumen indicate an oscillatory and random displacement pattern. This displacement pattern is not a realizable response of a viscoelastic material, and is therefore easily distinguishable from soft regions of tissue.

Figure 8. A graph of the Tissue Displacement Responses from different regions of the intermediately soft plaque (from figure 7).

The peak displacement from the soft regions (light green) in both views are 3 times larger than the peak displacement observed in the hard (dark blue) region of the plaque. Both the hard and soft regions exhibit typical displacement responses of tissue. This is contrasted with the partially random displacements observed in the lumen of the vessel, corresponding to the flow of blood.

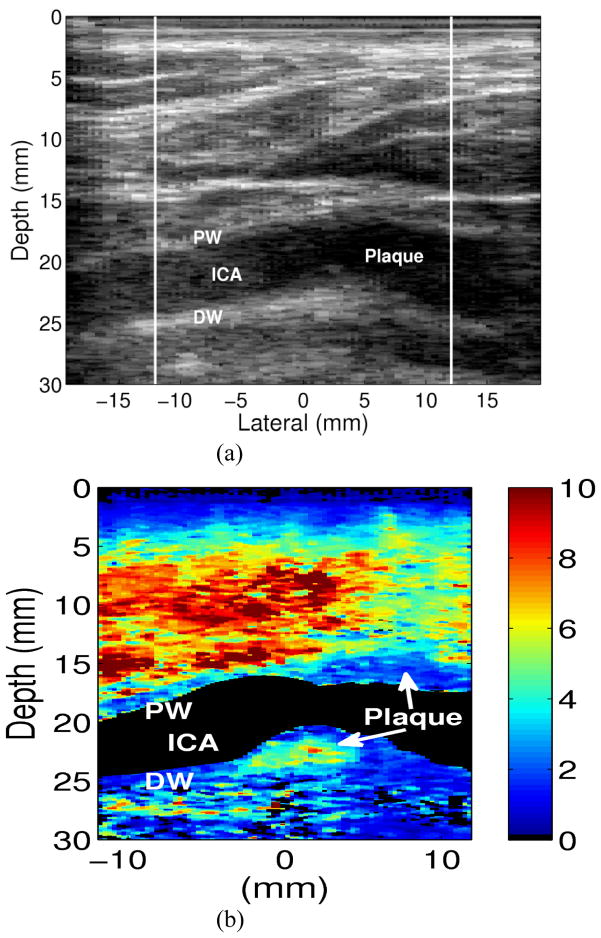

Figure 9 demonstrates a plaque containing a large soft core with a relatively thin cap from our previous demonstrations of ARFI imaging of carotid plaques50. This plaque has a stiff cap, as observed in the ARFI image, with a thickness of approximately 0.7 mm on the left side of the plaque. The remaining cap has a thickness of approximately 1.3 mm. This particular plaque meets all three of Ge’s criteria for plaque vulnerability14.

Figure 9. An Example of a Carotid Artery Containing an Soft Plaque Matched longitudinal.

(a) B-Mode and (b) ARFI images at the carotid bifurcation. The plaque is located on the distal wall (DW) of the bifurcation. The plaque appears to wrap around to the proximal wall (PW) in the region of the CCA. The relatively thin cap surrounding the soft region and the size of the soft region place this plaque in the vulnerable category, according to the characteristics described by Ge et al. [14]. Reprinted from permission from 50.

Discussion

ARFI Imaging

Our initial phantom and ex-vivo experiments indicate that viscoelastic differences in tissue deformational recovery rates from a displacement can be sensitively detected by ARFI analysis43. These differences are related to structural properties and allow us to discriminate between healthy and diseased tissue. These data support that ARFI provides a new vehicle for disease identification and localization. Additionally, ARFI images have resolutions comparable to conventional ultrasound imaging and are speckle free27. The findings are reproducible and show excellent stability over varying times of acquisition and viewing angles.

From our phantom, ex vivo and in vivo studies we are able to form several conclusions:

ARFI imaging shows excellent contrast and resolution of soft plaque-arterial wall boundaries, soft plaque, hard plaque boundaries, but often yields low contrast or no contrast at arterial wall/hard plaque boundaries.

In several cases, the ARFI image suggests sections of diseased tissue that are not readily apparent in the conventional ultrasound image.

ARFI imaging yields excellent definition of thick fibrous caps, but is challenged in resolving thin (0–0.5mm) fibrous caps. We hypothesize that these thin caps, in response to radiation force, move in unison with the underlying plaque material and are thus poorly resolved.

Another major practical advantage of ARFI over other imaging modalities is that because it only involves software modifications to diagnostic ultrasound scanners, many of the thousands of currently installed machines in clinical centers could be programmed to include co-registered ARFI and B-mode images without the addition of new equipment.

Application to Carotid Plaque Imaging

The benefits of endarterectomy in stroke prevention for patients with severe (>70%) carotid artery stenosis is clear3–5. As a result, the annual number of carotid endarterectomies performed in the United States has varied between 120,000 and 140,000 in each year since 199551. Currently there are no guidelines to further stratify these patients between those who are more or less likely to have an event. Many asymptomatic patients with severe stenosis may never suffer from a stroke and could be spared unnecessary endarterectomies if their plaques could be identified as stable. Given the fact that surgical risk for endarterectomy can be significant (3% for asymptomatic, 5% for symptomatic and TIA, 7% for recent, non-disabilitating stroke)52, identification of patients who would benefit the most from surgical intervention is important. A better way to identify the atherosclerotic plaques which confer the highest risk for stroke is fundamental to the selection of patients for vascular intervention It is likely that tens of thousands of patients each year could be spared endarterectomies if their plaques could be identified as stable.

For patients with high moderate (50–69%) stenosis the evidence of surgical benefit is less strong. In the NASCET trial, 858 patients with high moderate stenosis and previous symptoms of focal cerebral ischemia which persisted less than 24 hours or produced a non-disabling stroke were randomized into medical therapy or surgical treatment 6. The surgical complication rate in this trial was 2%. The five-year risk of treatment failure for ipsilateral stroke (fatal or non-fatal) was 22.2% for medically-treated patients and 15.7% for surgically-treated patients (p=0.045). This difference corresponded to a relative risk reduction of 29% whereby 15 patients would have to be treated by endarterectomy to prevent one ipsilateral stroke at five years 6. This is double the number required for patients with severe stenosis. Given that approximately 20% of these high-moderate stenosis patients show a natural progression rate (on medical therapy) to severe stenosis15, it would be of great clinical benefit to further identify the stable versus unstable and/or progressing plaques as early as possible.

ARFI imaging has the potential to add to the clinical information and decision making process for the work-up of patients with carotid artery stenosis. It could help to accurately, identify those high-risk patients with moderate stenosis for prophylactic surgical intervention prior to stenotic progression and ipsilateral ischemic events. Given the definition of vulnerable plaques described by Ge et al., 14 and the ARFI information shown in figure 6, it is clear that this patient would potentially be described as having a non-vulnerable plaque and consequently we would suggest is at low risk for stroke in the near future. Alternatively, the patient shown in figure 9 meets all the 3 criteria for plaque vulnerability and we would suggest is more likely to experience a cerebrovascular event. Unfortunately, the patient depicted in figure 7 falls somewhere in the middle of this vulnerability criteria (1 of the 3 factors) and may represent an individual that still defies further classification by ARFI imaging.

Limitations

Although ARFI imaging holds promise for vulnerable plaque detection there are several technical and practical limitations to this modality. These include the inability to identify the actual composition of tissues rather than just the relative softness/stiffness. For instance, one is unable to definitively say whether or not a particular region is calcified or lipid-filled in an ARFI image. The only conclusion that can be drawn is that one region is relatively stiffer than the other. Likewise, ARFI imaging has poor contrast for adjacent regions composed of similarly extremely compliant or extremely stiff tissue. For example, even though calcification is many times stiffer than fibrous plaque, an ARFI image would, in most cases, be incapable of distinguishing the two stiff tissues. This is because the image noise is greater than the observable differences in displacement between the two regions 53.

Some features of ARFI imaging that are readily apparent in excised vessels are not as apparent in vivo. For instance, differences in displacements observed in the individual layers of the vascular wall were apparent in excised vessel, but not in vivo. In addition, healthy vessel wall was distinguishable from fibrous and calcified regions in the excised vessels, but not in the in vivo arteries. These differences are largely due to the increased attenuation of the ultrasonic signal from the overlying tissue in the in vivo cases. The attenuating tissue decreases the ultrasonic signal-to-noise ratio as well as the applied force, making it more difficult to distinguish the stiff healthy tissue from the stiff diseased tissue.

Future Directions

Future studies in the development of ARFI imaging for detection of vulnerable carotid plaques should include matching ARFI images for patients scheduled for endarterectomy surgery with plaque histology when it is subsequently removed. This would allow measures of sensitivity and specificity to be attributed to the image sequences as compared to the “gold-standard” of tissue specimens. Additionally, large clinical trial confirmation that ARFI imaging can actually predict stroke events and allow better risk stratification is a major goal for the development of this technique.

Technical goals for ARFI imaging include real time scanning and analysis along with implementation into a clinic ultrasound unit, as well as heat management for real-time scanning. Implementation of real-time ARFI imaging is a relatively easy hurdle for commercial ultrasound systems, as the imaging sequence itself falls well within the software and hardware capabilities of these scanners. Heating of the transducer remains the largest concern for real-time ARFI scanning. The heating of the transducer depends largely on the number of ARFI pushes used in the imaging sequence and the rate at which these pulses are applied. This can be mitigated by the use of parallel beamforming, however careful management of the pulse rate seems to be the next most viable method for heat reduction. Frame rates on the order of color Doppler imaging seem to be the most viable for real-time ARFI imaging.

Summary/Conclusions

The findings presented in this paper provide evidence for the ability of ARFI to provide high quality images which highlight mechanical differences in tissue stiffness not readily apparent in matched B-mode images. This allows ARFI to identify soft from hard plaques and differentiate characteristics associated with plaque vulnerability or stability. Accurate identification of carotid plaque structural characteristics would substantially improve current stroke risk estimation and the surgical intervention decision-making process. The ARFI capability can be added, relatively easily, to current diagnostic ultrasound machines in clinics throughout the world.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ultrasound Division at Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. for their technical support.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

These findings were supported by the NIH grant R01-HL075485

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None

References

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y for the American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2007 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timsit S, Sacco R, Mohr J, Foulkes M, Tatemichi T, Wolf P, Price T, Hier D. Early clinical differentiation of cerebral infarction from severe atherosclerotic stenosis and cardioembolism. Stroke. 2007;23:486–491. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial C. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warlow C. Mrc european carotid surgery trial: Interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70–99%) or with mild (0–29%) carotid stenosis. The Lancet. 1991;337:1235–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Study ECftACA. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, Rankin RN, Clagett GP, Hachinski VC, Sackett DL, Thorpe KE, Meldrum HE, Spence JD The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial C. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1415–1425. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Fox AJ, Taylor DW, Mayberg MR, Warlow CP, Barnett HJM. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. The Lancet. 2003;361:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golledge J, Siew DA. Identifying the carotid ‘high risk’ plaque: Is it still a riddle wrapped up in an enigma? European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2008;35:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez CR. Carotid plaque morphology and risk for stroke. Stroke. 1990;21:148–151. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nandalur KR, Baskurt E, Hagspiel KD, Finch M, Phillips CD, Bollampally SR, Kramer CM. Carotid artery calcification on ct may independently predict stroke risk. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:547–552. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke AP, Farb A, Malcom GT, Liang Y-h, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary risk factors and plaque morphology in men with coronary disease who died suddenly. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1276–1282. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tearney GJ, Yabushita H, Houser SL, Aretz HT, Jang I-K, Schlendorf KH, Kauffman CR, Shishkov M, Halpern EF, Bouma BE. Quantification of macrophage content in atherosclerotic plaques by optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:113–119. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000044384.41037.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fayad ZA, Fuster V. Clinical imaging of the high-risk or vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. Circ Res. 2001;89:305–316. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge J, Chirillo F, Schwedtmann J, Gorge G, Haude M, Baumgart D, Shah V, von Birgelen C, Sack S, Boudoulas H, Erbel R. Screening of ruptured plaques in patients with coronary artery disease by intravascular ultrasound. Heart. 1999;81:621–627. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.6.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AbuRahma AF, Thiele SP, John T, Wulu J. Prospective controlled study of the natural history of asymptomatic 60% to 69% carotid stenosis according to ultrasonic plaque morphology. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2002;36:437–442. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.126545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabetai MM, Tegos TJ, Nicolaides AN, El-Atrozy TS, Dhanjil S, Griffin M, Belcaro G, Geroulakos G. Hemispheric symptoms and carotid plaque echomorphology. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2000;31:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(00)70066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tegos TJ, Stavropoulos P, Sabetai MM, Khodabakhsh P, Sassano A, Nicolaides AN. Determinants of carotid plaque instability: Echoicity versus heterogeneity. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2001;22:22–30. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabetai MM, Tegos TJ, Nicolaides AN, Dhanjil S, Pare GJ, Stevens JM. Reproducibility of computer-quantified carotid plaque echogenicity : Can we overcome the subjectivity? Stroke. 2000;31:2189–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tearney GJ, Jang I-K, Bouma BE. Optical coherence tomography for imaging the vulnerable plaque. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:021002. doi: 10.1117/1.2192697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Korte CL, Sierevogel MJ, Mastik F, Strijder C, Schaar JA, Velema E, Pasterkamp G, Serruys PW, van der Steen AFW. Identification of atherosclerotic plaque components with intravascular ultrasound elastography in vivo: A yucatan pig study. Circulation. 2002;105:1627–1630. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014988.66572.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaar JA, de Korte CL, Mastik F, Strijder C, Pasterkamp G, Boersma E, Serruys PW, van der Steen AFW. Characterizing vulnerable plaque features with intravascular elastography. Circulation. 2003;108:2636–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097067.96619.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabhudesai V, Phelan C, Yang Y, Wang RK, Cowling MG. The potential role of optical coherence tomography in the evaluation of vulnerable carotid atheromatous plaques: A pilot study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:1039–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0176-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawahara I, Morikawa M, Honda M, Kitagawa N, Tsutsumi K, Nagata I, Hayashi T, Koji T. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging using gadolinium-based contrast agent for atherosclerotic carotid plaque. Surgical Neurology. 2007;68:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saam T, Ferguson MS, Yarnykh VL, Takaya N, Xu D, Polissar NL, Hatsukami TS, Yuan C. Quantitative evaluation of carotid plaque composition by in vivo mri. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:234–239. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000149867.61851.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Touze E, Toussaint J-F, Coste J, Schmitt E, Bonneville F, Vandermarcq P, Gauvrit J-Y, Douvrin F, Meder J-F, Mas J-L, Oppenheim C for the H-RmrIiaSotCasg. Reproducibility of high-resolution mri for the identification and the quantification of carotid atherosclerotic plaque components: Consequences for prognosis studies and therapeutic trials. Stroke. 2007;38:1812–1819. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.479139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nightingale K, Bentley R, Trahey GE. Observations of tissue response to acoustic radiation force: Opportunities for imaging. Ultrasonic Imaging. 2002;24:129–138. doi: 10.1177/016173460202400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale K, Soo MS, Nightingale R, Trahey G. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: In vivo demonstration of clinical feasibility. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2002;28:227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nightingale KR, Nightingale RW, Palmeri ML, Trahey GE. A finite element model of remote palpation of breast lesions using radiation force: Factors affecting tissue displacement. Ultrasonic Imaging. 2000;22:35–54. doi: 10.1177/016173460002200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nightingale KR, Nightingale RW, Stutz DL, Trahey GE. Acoustic radiation forceimpulse imaging of in vivo vastus medialis muscle under varying isometric load. Ultrasonic Imaging. 2002;24:100–108. doi: 10.1177/016173460202400203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Nightingale RW, Trahey GE. On the feasibility of remote palpation using acoustic radiation force. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2001;110:625–634. doi: 10.1121/1.1378344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen D. Ultrasonic bioinstrumenatation. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker K. Ultrasonic attenuation and absorption in liver tissue. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1983;9:363–369. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(83)90089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalecki D. Mechanisms of interaction of ultrasound and lithotripter fields with cardiac and neural tissues. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nyborg WLM. Acoustic streaming. In: Mason WP, editor. Physical acoustics. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1965. pp. 265–331. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starritt HC, Duck FA, Humphrey VA. Forces acting in the direction of propagation in pulsed ultrasound fields. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 1991;36:1465. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/36/11/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torr GR. The acoustic radiation force. Am J Phys. 1984;52:402–408. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dahl JJ, Pinton GF, Palmeri ML, Agrawal V, Nightingale KR, Trahey GE. A parallel tracking method for acoustic radiation force impulse imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2007;54:301–312. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.FDA, Health CfDaR. Technical report. 1997. Information for manufacturers seeking marketing clearance of diagnostic ultrasound systems and transducers. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu KC, Rutt BK. Polyvinyl alcohol cryogel: An ideal phantom material for mr studies of arterial flow and elasticity. Magn Reson Med. 1997;37:314–319. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910370230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fromageau J, Brusseau E, Vray D, Gimenez G, Delachartre P. Characterization of pva cryogel for intravascular ultrasound elasticity imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2003;50:1318–1324. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2003.1244748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fromageau J, Gennisson JL, Schmitt C, Maurice RL, Mongrain R, Cloutier G. Estimation of polyvinyl alcohol cryogel mechanical properties with four ultrasound elastography methods and comparison with gold standard testings. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2007;54:498–509. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadkarni SK, Austin H, Mills G, Boughner D, Fenster A. A pulsating coronary vessel phantom for two- and three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound studies. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2003;29:621–628. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(02)00730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dumont D, Dahl J, Miller E, Allen J, Fahey B, Trahey G. Lower-limb vascular imaging with acoustic radiation force elastography: Demonstration of in vivo feasibility. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2009;56:931–944. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trahey GE, Palmeri ML, Bentley RC, Nightingale KR. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging of the mechanical properties of arteries: In vivo and ex vivo results. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2004;30:1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerhard-Herman M, Gardin JM, Jaff M, Mohler E, Roman M, Naqvi TZ. Guidelines for noninvasive vascular laboratory testing: A report from the american society of echocardiography and the society for vascular medicine and biology. Vascular Medicine. 2006;11:183–200. doi: 10.1177/1358863x06070516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baldewsing RA, de Korte CL, Schaar JA, Mastik F, van der Steen AFW. A finite element model for performing intravascular ultrasound elastography of human atherosclerotic coronary arteries. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:803–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng GC, Loree HM, Kamm RD, Fishbein MC, Lee RT. Distribution of circumferential stress in ruptured and stable atherosclerotic lesions. A structural analysis with histopathological correlation. Circulation. 1994;87:1179–1187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keeny SM, Richardson PD. Stress analysis of atherosclerotic arteries. Proc. IEEE Ninth Ann Conf Eng Med Biol Soc; 1987. pp. 1484–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee RT, Loree HM, Fishbein MC. High stress regions in saphenous vein bypass graft atherosclerotic lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1639–1644. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dahl JJ, Dumont DM, Allen JD, Miller EM, Trahey GE. Acoustic radiation force impulse imaging for noninvasive characterization of carotid artery atherosclerotic plaques: A feasibility study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:707–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halm EA, Tuhrim S, Wang JJ, Rojas M, Hannan EL, Chassin MR. Has evidence changed practice?: Appropriateness of carotid endarterectomy after the clinical trials. Neurology. 2007;68:187–194. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251197.98197.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bond R, Rerkasem K, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of the risks of carotid endarterectomy in relation to the clinical indication for and timing of surgery. Stroke. 2003;34:2290–2301. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000087785.01407.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmeri ML, McAleavey SA, Trahey GE, Nightingale KR. Ultrasonic tracking of acoustic radiation force-induced displacements in homogeneous media. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2006;53:1300–1313. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1665078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]