Abstract

The specification of the body plan in vertebrates and invertebrates is controlled by a variety of cell signaling pathways, but how signaling output is translated into morphogenesis is an ongoing question. Here, we describe genetic interactions between the Wingless (Wg) signaling pathway and a nonmuscle myosin heavy chain, encoded by the crinkled (ck) locus in Drosophila. In a screen for mutations that modify wg loss-of-function phenotypes, we isolated multiple independent alleles of ck. These ck mutations dramatically alter the morphology of the hook-shaped denticles that decorate the ventral surface of the wg mutant larval cuticle. In an otherwise wild-type background, ck mutations do not significantly alter denticle morphology, suggesting a specific interaction with Wg-mediated aspects of epidermal patterning. Here, we show that changing the level of Wg activity changes the structure of actin bundles during denticle formation in ck mutants. We further find that regulation of the Wg target gene, shaven-baby (svb), and of its transcriptional targets, miniature (m) and forked (f), modulates this ck-dependent process. We conclude that Ck acts in concert with Wg targets to orchestrate the proper shaping of denticles in the Drosophila embryonic epidermis.

Keywords: Wingless, Crinkled, Denticle, Morphogenesis, Drosophila embryo

INTRODUCTION

The ventral epidermis of Drosophila embryos is a well-established system for studying cell fate specification. At the end of embryogenesis, epidermal cells secrete a patterned array of cuticular structures that reflect the cell identities acquired in the epidermis at earlier stages of development. On the ventral surface of the larval abdomen, eight segmental belts of hook-shaped denticles alternate with expanses of flat, or naked, cuticle (Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein, 1985). Each belt contains roughly six rows of denticles, with each row displaying a characteristic size, shape and polarity (Bejsovec and Wieschaus, 1993). These distinct morphologies indicate unique positional values, at least some of which are imparted by signal transduction from the highly conserved Wg/Wnt growth factor pathway (reviewed by Bejsovec, 2006). During early embryogenesis, a cascade of transcription factors (reviewed by Akam, 1987) leads to activation of wg gene expression in segmental stripes that lie within the zone of cells that will secrete naked cuticle (Payre et al., 1999). Ectopic overexpression of wg across the segment (Noordermeer et al., 1992), or hyperactivation of downstream components in the Wg signaling pathway (Pai et al., 1997), eliminates the denticle belts. Conversely, loss of wg activity causes all ventral epidermal cells to secrete denticles (Nüsslein-Volhard et al., 1984). The diversity of denticles is also reduced in wg null mutants, with most resembling the large denticles typical of the fifth row of the wild-type belt (Bejsovec and Wieschaus, 1993). Thus Wg signaling controls not only the segmental specification of naked cuticle expanses, but also generates the diversity of cell fates that give rise to the uniquely shaped denticles within the denticle belt.

Denticles are formed by bundles of actin that accumulate apically and push out the apical membrane as they elongate (Dickinson and Thatcher, 1997; Price et al., 2006). Incipient denticles first can be visualized as apical actin condensations in the ventral epidermal cells of stage 13 embryos, at roughly 10 hours after egg-laying (AEL). These actin condensations form preferentially along the posterior edge of the columnar epithelial cells, and over the next 2 hours become increasingly more organized and begin to elongate; during this elongation phase, microtubules become enriched at the base of the denticle and also within the core of the growing denticle (Price et al., 2006). The mechanism by which the distinctive shapes of the denticles are specified is not well understood, but it requires Wg signaling between 4 and 6 hours AEL (Bejsovec and Martinez Arias, 1991). This early phase of Wg activity stabilizes expression of engrailed (en) and its target, hedgehog (hh), in the adjacent row of cells (Bejsovec and Martinez Arias, 1991; Heemskerk et al., 1991). Wg and Hh signaling together control the expression of Serrate and rhomboid, which activate the Notch and EGF pathways, respectively, in defined rows within the segment; these gene activities are required to specify the diverse denticle types characteristic of a wild-type denticle belt (Alexandre et al., 1999; Wiellette and McGinnis, 1999).

The organization of the actin-based denticle precursors and their transition to cuticular elements is directed by a set of structural proteins whose expression is controlled by the Wg-regulated transcription factor, Shaven-baby (Svb; Ovo – FlyBase). Wg signaling represses svb, restricting its ventral expression to the domain of cells fated to secrete denticles (Payre et al., 1999). Ectopic svb expression in the naked region of the embryonic epidermis drives formation of apical actin extensions and subsequent production of ectopic denticles (Delon et al., 2003). A number of downstream targets of Svb have been identified; these include genes such as singed (sn) and forked, which encode known actin-remodeling proteins, and miniature, which encodes a membrane-anchored extracellular protein thought to mediate interaction between the cell membrane and the cuticle (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006; Fernandes et al., 2010). However, the question remains as to how these structural proteins are deployed to form the distinct morphologies characteristic of each row of denticles. We show here that the cytoplasmic myosin, Crinkled, interacts genetically with the Wg signaling pathway and plays a role in organizing the final shapes of the denticles during epidermal development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and culture conditions

The new ck alleles, ckAN9, ckCB16, ckKT9, ckPJ17, ckPS10 and ckPT14, were generated in an ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) screen described in Jones and Bejsovec (Jones and Bejsovec, 2005). The sn3, m1 and f1 stocks, Gal4 driver lines, UAS-svb, and all deficiencies were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. The Tcf (Cavallo et al., 1998) and SoxN (Chao et al., 2007) mutations, and the hs-wg+ and UAS-wg+ transgenes (Hays et al., 1997), were generated in our laboratory and all are available at the Bloomington Stock Center. The ck7 allele and UAS-ckGFP transgene were gifts from D. Kiehart (Duke University, NC, USA). Flies were reared on cornmeal-agar-molasses and embryos were collected on apple juice agar plates; all were cultured at 25°C except in temperature shift and heat shock experiments. For temperature shifts, embryos were collected at 1-hour intervals, aged at 18°C for 16 hours, which corresponds to 8 hours of developmental time at 25°C, and then shifted up to 25°C to complete development. For heat shocks, embryos were collected in a 2-hour interval, aged 2 hours at 25°C, dechorionated in wire mesh baskets and cultured in distilled water. Baskets were transferred to containers floating in a 37°C water bath for 3× 20-minute heat shocks, separated by 1-hour recovery incubations at room temperature.

Embryo and larval imaging

To examine embryonic and larval cuticles, eggs were allowed to develop fully (24 hours at 25°C), dechorionated in bleach, and transferred to a drop of Hoyer’s medium, mixed 1:1 with lactic acid (Wieschaus and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1986), on a microscope slide. Vitelline membranes were burst by exerting gentle pressure on the coverslip. First instar larvae were collected immediately after hatching, transferred directly into Hoyer’s medium, and flattened with a coverslip. Cuticle preparations were baked at 65°C overnight before viewing on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope with phase contrast optics. For each genotype, at least 100 mutants were examined and the most representative phenotype was selected for imaging. ck homozygous mutants were distinguished from wild-type siblings based on their distinctive dorsal hair defect.

For rhodamine phalloidin staining, embryos were collected in 1-hour intervals, aged to specified developmental time, dechorionated in bleach, fixed for 30 minutes in 4% formaldehyde in PEM buffer (0.1 M Pipes, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgSO4, pH 6.9), rinsed with heptane, transferred to double-sided 3M tape, and hand-devitellinized in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) using a small-gauge syringe needle. For antibody staining, embryos were fixed as above but devitellinized in methanol/heptane, preincubated in 10% BSA and processed with 1% BSA in PBS with 0.1% Tween20. Rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes) was used at 1:500, anti-GFP antibody (Millipore) was used at 1:500 and En antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) was used at 1:50. Secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used at 1:500. Embryos were mounted in Aquapolymount (Polysciences) and viewed with a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope.

For scanning electron microscopy, freshly hatched larvae were fixed overnight in 23% glutaraldehyde buffered with phosphate, rinsed with distilled water and oriented on agar slabs to preserve hydration. Slabs were trimmed to fit on EM stubs and imaged using an environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) with EDS detector (Model: FEI XL30 ESEM).

RESULTS

wg mutant background reveals a role for Ck in denticle formation

In a genetic screen for mutations that modify the cuticle pattern of wg mutant embryos, we recovered six independent lines where all of the wg homozygotes show a dramatic alteration in the morphology of the ventral denticles. In typical wg loss-of-function mutants, the denticles are large and strongly hooked, with the direction of the hook alternating between posterior and anterior in a segmentally repeating pattern (Fig. 1A,C). The denticles lack the diversity of morphologies and stereotyped polarities found in wild type (Fig. 1B,D,E). In embryos that carry the wg modifier mutations, the denticles are rounded and do not form a sharply pointed hook, so that polarity is not discernible (Fig. 1E,F).

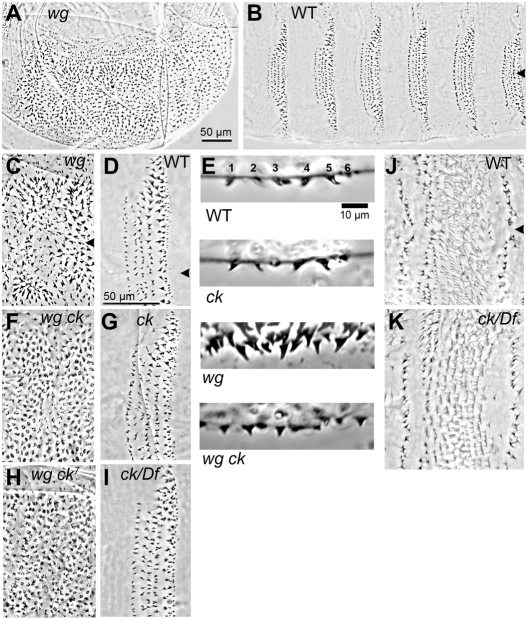

Fig. 1.

Mutations in ck disrupt denticle morphology in a Wg-dependent manner. (A) wgCX4 null mutants produce a ‘lawn’ of ventral denticles and lack the naked cuticle that separates the eight abdominal denticle belts in the wild-type cuticle (B). In this and all subsequent images anterior is to the left. Arrowheads in B-D mark the ventral midline. (C) Higher magnification of the wgCX4 ventral cuticle reveals that the large, curved denticles are arranged in a segmental pattern of reversed polarities, and lack the diversity of morphologies seen in the wild-type denticle belt (D). (E) A single denticle belt in profile shows the subtle differences between wild-type (top, labelled for denticle row number) and ckAN9 homozygous denticle morphologies, versus much greater differences between the wgCX4 and wgCX4 ckAN9 (bottom) mutant denticles. (F) ckAN9, or any of the other six ck alleles isolated in our genetic screen, causes wgCX4 mutant denticles to have a rounded appearance and lack a distinctive hook. (G) ckAN9 homozygotes on their own do not show obvious denticle morphology defects. (H) Existing alleles of ck such as ck7 produce the same rounded modification of the wg mutant denticle. (I) Placing ck alleles (ckKT9 shown here) in trans with a deficiency does not alter denticle morphology. (J) Segmental pattern on the dorsal surface consists of trichomes and a field of fine hairs in wild type. The arrowhead marks the dorsal midline. (K) The fine hairs are dramatically truncated and frequently misoriented in ckKT9 homozygous or hemizygous mutants, making them easily distinguished from wild-type siblings.

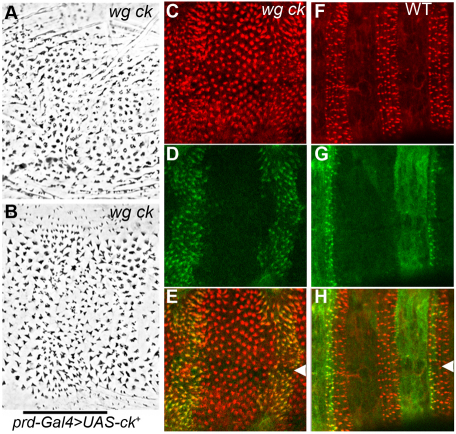

The genetic behavior of these lines indicated that they each carried a mutation linked to the wg mutation on the second chromosome. All six modifier mutations failed to complement each other, indicating that they are allelic. Recombination mapping and deficiency analysis narrowed down the position of the gene affected. We tested existing lethal mutations within this interval (Tweedie et al., 2009) and found that mutations at the crinkled (ck) locus failed to complement the lethality of our modifier mutations. ck encodes the Drosophila myosin VIIA heavy chain, a cytoplasmic myosin that is broadly expressed during development (Kiehart et al., 2004). Most ck alleles are semi-lethal, with adult escapers that show crumpled and/or forked bristles (Nüsslein-Volhard et al., 1984). Our new alleles are 100% lethal during larval stages, both as homozygotes and in trans with a deficiency. We sequenced the ck gene in each of our independent modifier lines and found that each contains a mutational change from the wild-type ck sequence (Table 1). Three mutations, KT9, PS10 and PT14, create premature stop codons, and two mutations, AN9 and CB16, introduce nonconservative amino acid changes in the motor domain, which is highly conserved between flies and humans (Kiehart et al., 2004). The last mutation, PJ17, disrupts the splice site of the eleventh intron; failure to splice would introduce 20 novel amino acids and a premature stop codon.

Table 1.

ck alleles isolated as modifiers of wg mutant phenotypes

In the course of mapping these mutations, we isolated chromosomes bearing the modifier mutation separated from wg. Embryos homozygous for these recombinant ck chromosomes showed only mild denticle morphology aberrations compared with wild type (Fig. 1G, compare with 1D), and this zygotic phenotype was no more severe when the ck alleles were placed in trans with a deficiency for the region (Fig. 1I). However ck homozygous mutants show a dramatic shortening of the fine hairs on the dorsal surface of the cuticle, making identification of homozygotes unambiguous (Fig. 1J,K). The wg-associated effect on denticle morphology was most easily seen in a side view of one denticle belt (Fig. 1E), where each of the six rows of denticles in a wild-type segment displays its characteristic size and shape; only minor differences in this array were seen in ck single mutants. This contrasts with the dramatic difference in denticle morphology between wg mutants and wg ck double mutants: whereas most denticles in wg single mutants are large and point sharply in a segmental pattern of polarity reversals, the denticles in wg ck mutants are small and show no anteroposterior polarity because they lack distinctive hooks.

We were surprised that our ck mutations strongly modify the denticles of wg mutants but only slightly alter ventral denticle structure in an otherwise wild-type genetic background. We wondered whether this indicated some special property of the alleles that were isolated in our wg modifier screen. Therefore we tested previously isolated alleles of ck, but found that these also alter the morphology of the denticles in double mutant combinations with wg. For example, ck7, a semi-lethal nonsense allele that truncates the protein at L1445 (Kiehart et al., 2004), in combination with wg produces a cuticle pattern indistinguishable from that of our modifier mutant lines (Fig. 1H). We conclude that a general loss of ck function disrupts the morphology of denticles produced by wg mutant embryos.

Actin bundle elongation is delayed in ck mutants

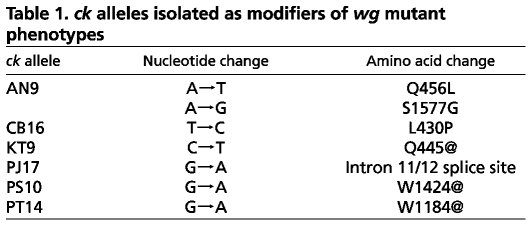

To explore the nature of this shape change, we examined the structure of the denticles as they form during embryogenesis. A denticle is produced by a bundle of actin filaments that pushes out the apical membrane before cuticle deposition, which begins at 16 hours AEL. Apical bundles of filamentous actin can be detected in epidermal cells, starting at roughly 10 hours AEL (Fig. 2A). In wild-type and wg mutant embryos these bundles begin as round aggregations that progressively acquire the hooked shape of the denticles over the next 4 hours (Fig. 2B,C,F,G), and which are stabilized by microtubule accumulation at the base of the denticle (Fig. 2E). By 14 hours AEL, the actin bundles strongly resemble the final shape of the mature denticle, although the reversed polarity of denticles in rows 1 and 4 is not observed (Dickinson and Thatcher, 1997). The reversal is presumed to occur some time after cuticle deposition begins; cuticle secretion prevents the molecular detection of this process because antibodies and stains cannot penetrate the cuticle and the twitching of the embryonic musculature at late stages interferes with live imaging (Martinez Arias, 1993; Dilks and DiNardo, 2010). In ck mutant embryos, we found that the apical actin aggregations did not mature into the final denticle shapes. They formed at 10 hours but remained rounded even at and after 14 hours AEL (Fig. 2D). As with the row 1 and 4 polarity reversal, the final shaping of these denticles must occur at a point later than we can detect, as the mature cuticles of ck mutant larvae clearly show sharply pointed denticles (Fig. 1G). The wg ck double mutants also showed apical actin aggregations starting at 10 hours, which remained rounded at 14 hours (Fig. 2H). However, we presume that these aggregations do not transition to a pointed shape before cuticle deposition because the mature denticles appear rounded (Fig. 1F). Thus the difference between ck single and wg ck double mutant embryos occurs at a time point in denticle construction that cannot be assayed molecularly and that could be related to the deposition of cuticle.

Fig. 2.

ck mutation alters the timing of actin bundle maturation in developing denticles. (A) Rhodamine phalloidin staining of stage 13 embryos (10 hours AEL) reveals apical actin filament aggregations in the ventral epidermal cells that will produce denticles. (B) The bundles of actin filaments elongate over the next 2 hours, and by 14 hours AEL (C), the incipient denticles have acquired the size and shape that will be represented in the cuticle pattern. (D) Actin bundles in ckKT9 homozygous mutants have not elongated properly or assumed their mature shape at 14 hours AEL. Other morphological landmarks, including a three-part gut, marked this embryo unequivocally as late stage 15. (E) At late stages, the mature denticles also show aggregation of microtubules (marked by α-tubulin-GFP, green) at the base of the actin bundles (yellow in merge). (F) In wgCX4 mutants, actin bundles begin to elongate at 12 hours AEL and assume their mature shape by 14 hours AEL (G). (H) wgCX4ckKT9 double mutants have actin bundles that remain rounded at and after 14 hours AEL.

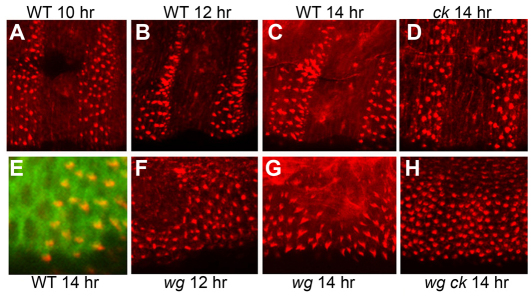

We can demonstrate that this difference is due to Ck function by providing ectopic Ck product. Expressing a GFP-tagged full-length ck transgene (Todi et al., 2005) in the embryonic epidermis of wg ck mutants rescued the pointed appearance of the denticles within the transgene expression domain (Fig. 3A,B). This rescue was also observed in the shaping of the apical actin bundles in late-stage wg ck embryos (Fig. 3C). Using prd-Gal4 to drive Ck only in the odd-numbered segments allowed us to see that this rescue was cell-autonomous, occurring only in the regions of the epidermis where the transgene is expressed (Fig. 3D,E). The GFP-tagged Ck in both wild-type and wg mutants localized to actin bundles in the denticle-producing cells (Fig. 3C-H). In wild-type embryos (Fig. 3F-H), we found that Ck protein in non-denticle-producing epidermal cells showed a more diffuse cytoplasmic staining, indicating that Ck is recruited to the apical actin cytoskeleton specifically during denticle construction. This dramatic localization pattern of Ck-GFP in the denticle-secreting cells is consistent with the idea that Ck myosin may play a role in shaping the actin bundles as they form incipient denticles.

Fig. 3.

Denticle shape can be rescued by providing ectopic ck. (A,B) wgCX4ckKT9 double mutants secrete a uniform lawn of rounded denticles that are rescued to a pointed, hooked appearance (B) when prd-Gal4 drives ectopic expression of a wild-type ck transgene in odd-numbered segments, marked by bar. (C) Rhodamine phalloidin staining in 14-hour AEL wgCX4ckKT9 double mutants also detects rescued elongation and shaping of actin bundles in the domains expressing UAS-ck.(D,E) The GFP-tagged ck product accumulates strongly in incipient denticles of these wgCX4ckKT9 mutants (merge, E) and this distribution coincides perfectly with those denticles that are rescued. (F) Wild-type siblings show no structural alteration of denticles where ck is overexpressed. (G) Much of the prd expression domain in a wild-type embryo underlies naked cuticle, showing that GFP-tagged ck remains cytoplasmic in non-denticle-secreting cells and is recruited to the denticles in denticle-secreting cells (merge, H). Arrowheads mark the ventral midline.

Different Wg signaling levels produce distinct ck mutant denticle morphologies

To determine the extent to which Wg signaling influences denticle shape in ck mutants, we reduced the level of Wg signaling in embryos by using a partially functional wg allele. The wgPE2 lesion introduces a single amino acid substitution (Bejsovec and Wieschaus, 1995) that disrupts interaction of the mutant protein with proteoglycan co-receptors and thereby eliminates the high threshold naked-cuticle specifying activity of the molecule (Moline et al., 2000). The cuticle patterns secreted by wgPE2 homozygotes show the denticle diversity characteristic of a wild-type denticle belt but have little naked cuticle separating the denticle belts (Fig. 4A). In the wgPE2 ck double mutant, the arrangement of the denticles was not substantially altered but in many rows the denticles appear less sharply pointed or hooked (Fig. 4B, compare A′ and B′). This was most noticeable in the more posterior rows in each belt, which tend to produce large denticles, such as those typical of row 5 (Fig. 1E): these appeared flattened and fragmented, especially along the dorsolateral edge of the denticle field (arrow in Fig. 4B). This fragmented appearance suggested that the underlying bundles of actin had not aggregated properly. Indeed, rhodamine phalloidin staining of wgPE2 ck double mutant embryos at 14 hours AEL showed that the bundles of actin assume a ring-like shape, rather than a cohesive bundle (Fig. 4C). Thus, whereas the reduced level of Wg activity produced from the wgPE2 allele was sufficient to partially rescue the pointed morphology of smaller ck mutant denticles found in the anterior rows of the belt, the larger posterior denticles were not rescued and instead showed a novel phenotype where the actin bundles failed to coalesce.

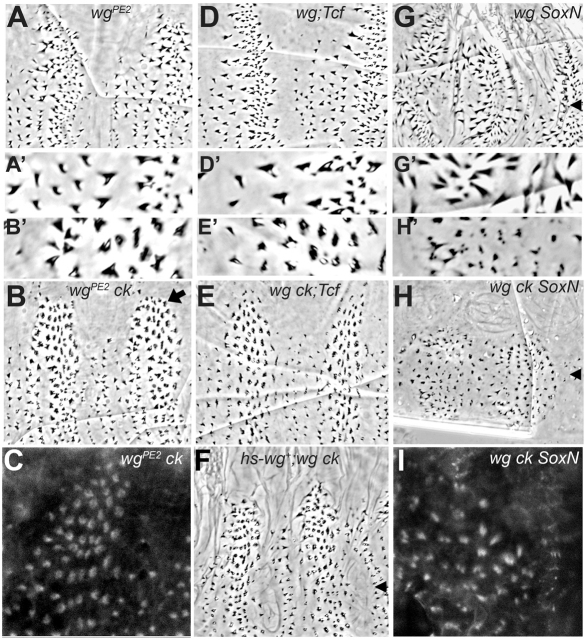

Fig. 4.

Intermediate Wg levels alter the appearance of ck mutant denticles. (A) wgPE2 homozygotes have sufficient Wg activity to generate diverse denticle types, but not naked cuticle. (A′) Enlarged view of denticles from A. (B) Denticles in anterior rows of wgPE2 ckKT9 segmental belts are pointed and hooked, but larger denticles in posterior rows remain rounded and appear fragmented (enlarged in B′), particularly along the dorsolateral edge (at top, arrow). (C) Rhodamine phalloidin staining of 14-hour AEL embryos shows ring-shaped actin structures that correlate with fragmentation in the dorsolateral epidermal cells. (D) wgCX4;Tcf2 double mutants restore denticle diversity to the wg phenotype (enlarged in D′), but without positive pathway activation by Tcf, naked cuticle cannot be specified. (E) In wgCX4ckKT9;Tcf2 triple mutants, smaller anterior denticles can acquire sharp points, but larger posterior denticles remain rounded and some appear fragmented (enlarged in E′). (F) The wgCX4 ckKT9 mutant phenotype can be partially rescued by uniform wild-type wg from a heat-shock-promoter-driven transgene. Under these conditions, smaller anterior denticles are more completely rescued than larger posterior denticles. Arrowheads in F-H mark the ventral midline. (G) wgCX4 SoxNNC14 double mutants restore some segmentation to the wgCX4 mutant pattern. (H) wgCX4ckKT9SoxNNC14 triple mutants show a dramatic reduction in denticle size and many of the denticles are fragmented into two or more short projections (compare G′ with H′). (I) Rhodamine phalloidin staining of wgCX4ckKT9SoxNNC14 triple mutants shows that apical actin filaments aggregate abnormally into multiple bundles.

The differential effect on posterior-row denticles could be explained in one of two ways. First, because these are the largest denticles within the belt, they may have the greatest requirement for Ck myosin in shaping their actin bundles, and therefore may be disproportionately sensitive to reduced Wg signaling and the loss of ck. Alternatively, since these denticles are positioned furthest from the wg-expressing cells within the segment, they presumably receive less Wg signal than other denticle-secreting rows of cells and so are closer to a null wg condition. To distinguish between these possibilities, we manipulated Wg pathway activity in other ways. The Tcf transcription factor acts as either a repressor or an activator depending on Wg signaling levels (Cavallo et al., 1998). Tcf mutations partially suppress wg loss-of-function phenotypes owing to derepression of target genes: double mutant embryos produce a cuticle pattern similar to that of wgPE2 mutants (Fig. 4D). Removing ck function from the wg;Tcf double mutants produced an effect similar to wgPE2 ck, with larger posterior-row denticles appearing flattened and fragmented whereas some smaller anterior-row denticles were able to acquire sharp points (Fig. 4E, compare Fig. 4D′,E′). As wg was not expressed at all in this experimental condition, we conclude that posterior-row denticles are differentially affected because of their larger size. Likewise, we can provide wg product uniformly within the wg null mutant embryo, using a heat-shock promoter-driven wild-type Wg transgene. High levels of ectopic wg+ eliminate the denticles, but hs-wg+ administered with mild heat shocks produces partial rescue of the wg mutant segmental pattern, restoring diverse denticle types separated by naked cuticle (Hays et al., 1997). When we expressed hs-wg+ in wg ck double mutant embryos, we found a similar rescue of pattern, and in addition a rescue of the pointed shapes of the smaller anterior denticles, with little rescue of the larger posterior-row denticles (Fig. 4F). We conclude that the larger denticles have a greater need for Ck function under conditions in which Wg signaling is compromised.

We found that lower levels of uniform wg target derepression produces a slightly different effect on denticle structure from that observed in the wg;Tcf double mutant. Mutations in the SoxNeuro (SoxN) transcription factor slightly suppress wg loss-of-function phenotypes, restoring stronger segmentation to the pattern without substantially increasing denticle diversity (Chao et al., 2007). Removing ck function in this genetic background reduced the size of the denticles and caused a more extensive fragmentation of the mature denticles (Fig. 4G,H). Phalloidin staining of the wg ck SoxN triple mutant embryos revealed a splitting of the actin bundles into two and sometimes three separate aggregates (Fig. 4I). We observed a similar effect on the denticles when we examined other genetic conditions that cause a slight suppression of wg loss-of-function phenotypes. For example, the wg;naked (nkd) double mutant produces a weak segmentation similar to the one shown for wg SoxN (Bejsovec and Wieschaus, 1993), and the wg ck;nkd triple mutant shows splitting of the denticles similar to that observed for the wg ck SoxN triple mutant (data not shown). Thus we can detect different phenotypic effects of ck disruption that depend on the level of Wg signaling activity within the developing epidermis. ck mutant embryos show relatively normal coalescence of actin filaments into bundles under wild-type levels of Wg signaling, although there is a delay in the transition to the mature hooked denticle shape, such that it occurs after cuticle deposition begins. In ck mutants with no Wg signaling, actin bundles form but do not resolve into the hooked shape of the mature denticle at all. In contrast, low levels of Wg signaling appear to disrupt the coalescence of the ck mutant actin bundles, creating a more severe phenotype of fragmentation in addition to the failure to elongate and mature into a hooked shape. This loss of actin bundle integrity can be generated directly by ligand-independent transcription of downstream Wg target genes, for example by removal of the repressors Tcf or SoxN, suggesting that Ck interacts with Wg targets rather than some upstream portion of the Wg pathway.

ck mutant background reveals different thresholds for Wg signaling

We further tested the differential effect of Wg signaling by restoring wg expression within restricted regions of the wg ck null embryonic epidermis. We used paired-Gal4 to drive wild-type wg expression in odd-numbered abdominal segments. In a wg single mutant, this condition fully rescued naked cuticle in the odd-numbered segments and substantially rescued denticle diversity in the epidermal cells adjacent to the paired (prd) expression domain (Fig. 5A). A similar rescue of naked cuticle occurred in the wg ck double mutant embryos, but the denticle morphologies were not rescued: the larger denticles showed the ring-like fragmentation phenotype characteristic of low-level Wg signaling (Fig. 5B). Conversely, loss of ck function does not compromise Wg signaling or Wg protein movement. Wg protein distribution is normal in ck mutant homozygotes, as is the expression of en, a Wg target gene expressed in the rows of cells just posterior to the normal wg expression domain (data not shown). Furthermore, prd-driven wg+ rescued the expression of en in the odd-numbered segments of wg and wg ck mutants (Fig. 5C,D, versus 5E) where it was also expanded relative to the normal en expression domain (Fig. 5F). Wg moving from this source domain into the adjacent even-numbered segment was sufficient to rescue and expand the en expression at the ventral midline of the segment (arrow in Fig. 5C). We observed a similar rescue of en expression in the wg ck double mutant (arrow in Fig. 5D), indicating that this process was not affected by loss of ck function. As denticle morphology at the ventral midline of wg ck mutants was not rescued, we conclude that the level of Wg activity required for controlling en target gene expression is lower than that required for Ck-mediated denticle morphogenesis.

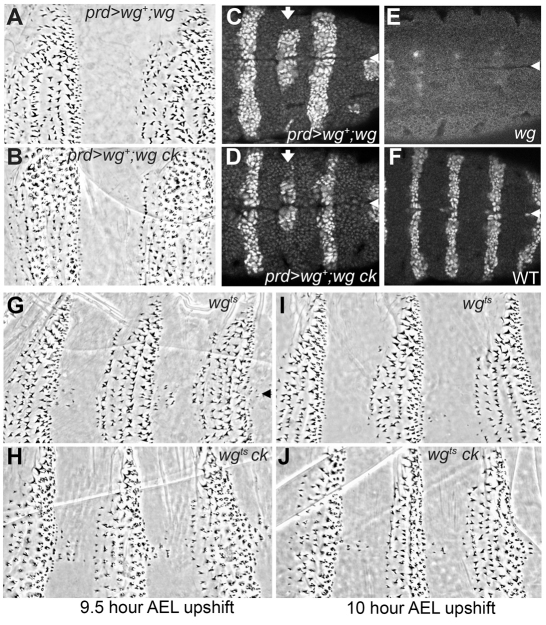

Fig. 5.

Wg is required at late stages and at high levels for proper ck mutant denticle morphology. (A) prd-Gal4 driven UAS-wg+ transgene expression in the epidermal cells of odd-numbered segments rescues naked cuticle in a wgCX4 null mutant, and also denticle diversity in even-numbered segments. (B) In wgCX4ckKT9 double mutants, prd-Gal4 driven wg+ shows similar rescue, but most denticles remain rounded in appearance and there is some fragmentation of the large denticles. (C) Engrailed antibody staining in stage 10 prd>wg+;wgCX4 mutant embryos shows rescue and expansion of en expression in odd-numbered segments, and rescue at the ventral midline in even-numbered segments (arrow). Arrowheads in C-G mark the ventral midline. (D) The same degree of rescue is observed in wgCX4ckKT9 double mutants. (E,F) Without the rescuing transgene, en expression disappears from the epidermis of wg mutants by stage 10, compared with normal stripes of en expression in wild-type embryos at this stage (F). (G) Shifting wgts homozygous mutants up to restrictive temperature at 9.5 hours AEL results in a diverse denticle belt pattern but incomplete specification of the naked cuticle zone. (H) wgtsckKT9 double mutants shifted at the same time point show similar pattern effects but many denticles remain rounded in appearance, particularly the large posterior denticles. (I) Normal denticle patterning is largely restored in wgts mutants shifted up at 10 hours AEL, but morphological defects are still detected in the posterior-row denticles of wgtsckKT9 double mutants shifted at the same time point (J).

ck mutant denticle formation requires late Wg signaling

We next asked when during development Wg signaling is required to produce this effect on ck mutant denticles. Experiments with a temperature-sensitive allele of wg revealed that Wg signaling between 4 and 6 hours AEL generates the diversity of cell fates that give rise to the uniquely shaped denticles (Bejsovec and Martinez Arias, 1991). Wg signaling after 6 hours correlates with the specification of progressively more naked cuticle (Fig. 5G), with this aspect of epidermal patterning virtually complete by 10 hours AEL (Bejsovec and Martinez Arias, 1991). We generated a wgts ck stock and tested the temporal requirement for wg in the ck denticle morphology phenotype. We found that loss of Wg function at 9.5 hours, long after the time when denticle cell fates are specified, resulted in the rounded appearance of the larger, posterior row denticles (Fig. 5H). Even in wgts ck embryos shifted to restrictive temperature at 10 hours AEL, the row 5 denticles were not properly elongated and hooked (Fig. 5J), whereas patterning in wgts mutants shifted at this time was almost wild type (Fig. 5I). Thus we conclude that some continuing aspect of Wg signaling influences the shaping of denticles in ck mutants.

Svb target genes modify the ck denticle phenotype

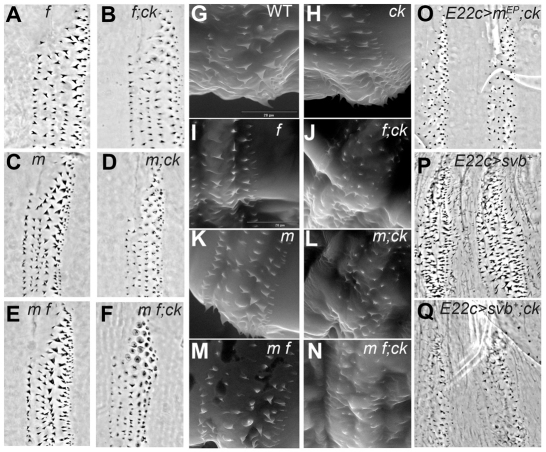

We next asked how the Wg pathway might influence the ability of Ck to organize actin bundles and the denticles they form. Wg signaling represses expression of the transcription factor ovo/shaven-baby (svb) within the naked cuticle-secreting portion of the embryonic segment (Payre et al., 1999). This restricts svb to the denticle-secreting portion of the segment, where its activity promotes expression of a suite of genes that shape the denticles (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006). We examined known Svb targets to determine whether they might be involved in the denticle morphology changes associated with the wg ck phenotype. singed (sn) and forked (f) encode actin-associated proteins, and are strongly upregulated in the denticle-secreting cells of the segment in an Svb-dependent manner (Chanut-Delalande et al., 2006). Mutations in either gene subtly alter denticle shape (Dickinson and Thatcher, 1997), but the denticles retain their pointed and hooked appearance. We found that sn;ck double mutants did not appear significantly different from sn single mutants (not shown), whereas f;ck double mutants did show a slight reduction in the sharpness of the denticles relative to f single mutants (Fig. 6A,B). A more dramatic effect was observed with the Svb target gene miniature (m). This gene encodes a membrane protein that interacts with cuticle (Roch et al., 2003). Mutants lacking m function produce pointed denticles that are less strongly hooked than wild-type denticles (Fig. 6C), whereas m;ck double mutants have denticles that are reduced in both size and sharpness (Fig. 6D). This effect was enhanced when f function was also removed. Although the m f double mutant denticles do not look significantly different from those of m single mutants (Fig. 6C,E), the m f;ck triple mutant embryos produce denticles that are strongly reduced, rounded and/or fragmented, particularly along the dorsolateral edges of the denticle belt (Fig. 6F). These denticles, especially those in row 5, resemble those of the wg ck double mutants.

Fig. 6.

Svb target genes modify the ck mutant phenotype. (A) Larval cuticles produced by f homozygous mutants have slightly narrower denticles than wild type, and this effect is enhanced in f;ck double mutant larval cuticles (B). The sn, f, m and m f mutants are homozygous viable, and balanced ck mutant stocks were created for each of these homozygous mutant backgrounds. ck homozygous mutant larvae were recognized by their dorsal hair defects. (C,D) m mutant larvae produce thick, broad denticles, but these are dramatically reduced in m;ck double mutant larvae (D). (E,F) m f double mutant larvae (E) produce denticles similar to those of m single mutant larvae, but m f;ck triple mutant larvae (F) show flattened and fragmented denticles, especially in the posterior rows. (G-N) ESEM images of larval cuticles: (G) wild-type larvae show the normal arrangement of distinct denticle types within a belt. (H) ck mutant denticles consistently appear slightly smaller than those of wild-type. (I,J) f mutant denticles (I) are thinner and show a marked reduction in size in the presence of the ck mutation (J). (K,L) m mutant denticles (K) also show a strong reduction in size in the presence of the ck mutation (L). (M,N) m f mutant denticles (M) show almost no elongation in the presence of the ck mutation (N). (O) Driving m expression ubiquitously in the epidermis of a ck mutant embryo produces a strong reduction in denticle size. (P) Driving ubiquitous expression of svb produces ectopic small denticles in the naked cuticle regions, but also disrupts the normal arrangement and morphology of denticles in the denticle belts. (Q) Driving ubiquitous expression of svb in a ck mutant causes a strong reduction in denticle size and shape, and virtually eliminates the ectopic denticles between belts.

To get a clearer view of the mature denticles, we used an ESEM to obtain images of first instar larvae. These larvae remain fully hydrated, preserving the integrity of the cuticle. Under these conditions, slight reductions in denticle size and degree of hooking were detected in the ck single mutants relative to wild type (Fig. 6G,H). Combining a ck mutation with either f (Fig. 6I,J) or m (Fig. 6K,L) dramatically reduced the size and degree of hooking of the denticles when compared with each single mutant. The loss of all three gene activities virtually eliminated the ability of the denticles to elongate (Fig. 6M,N), indicating that the m and f gene products play an important role in the ck-mediated construction of denticles.

We were surprised to find that m and f loss of function modified the ck mutant denticles in the same way that loss of wg function does. Loss of wg results in high levels of svb expression uniformly throughout the ventral segment (Payre et al., 1999), and presumably this drives high expression of target genes such as m and f. One possible explanation for our unexpected observation is that the precise level of these gene products must be carefully controlled during denticle morphogenesis, and either an increase or a decrease in their activity can affect the shape of the denticle as it forms. To test this, we overexpressed m in the embryonic epidermis. In a wild-type background, this had no effect on denticle structure (data not shown), but in the ck mutant background, m overexpression disrupted the morphology of denticles in a manner similar to reduced m function (Fig. 6O). The idea of component imbalance was also supported by experiments perturbing the expression of svb itself. We found that driving ubiquitous expression of svb in the embryonic epidermis not only produced ectopic denticles in the naked cuticle zone, as previously reported (Payre et al., 1999), but also disrupted the morphology of denticles within the segmental belts (Fig. 6P). Furthermore, driving ubiquitous expression of svb in a ck mutant dramatically reduces denticle size and alters morphology (Fig. 6Q). These observations suggest that ck mutants are particularly sensitive to the level of Svb target gene expression during denticle formation. We therefore conclude that it is the deregulation of svb and its targets that accounts for the dramatic loss of denticle shaping that we observed in the original wg ck double mutants.

DISCUSSION

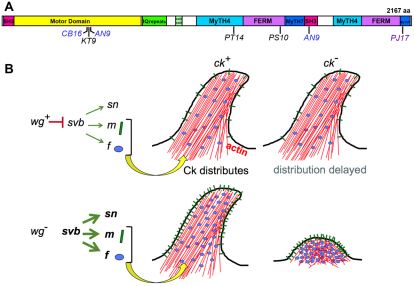

Our genetic screen for modifiers of wg mutant phenotypes revealed an unexpected interaction between Wg signaling and the cytoplasmic myosinVIIA homolog, Ck, in shaping the denticles at late stages of embryonic development. Like other myosins, Ck/myosinVIIA has a typical actin-binding/ATPase head domain that mediates movement along actin filaments (Fig. 7A). However, the carboxy-terminus of Ck/myosinVIIA is unique in containing an SH3 domain and two FERM domains, which are shared by band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin – a family of proteins that link the actin cytoskeleton to membrane spanning proteins (Hasson, 1999; Kiehart et al., 2004). These motifs are consistent with a role near the plasma membrane, possibly interacting with cell-surface receptors and/or adherens junctions. This raises the possibility that Ck may be involved in the association between the actin bundles of the incipient denticles and the apical membrane, where it could link the actin cytoskeleton to extracellular components of the cuticle through transmembrane proteins such as Miniature. Either loss or gain of function for the Wg target gene svb alters denticle morphology in the ck mutant background. Therefore, we propose that Ck myosin may help to distribute the products of some Svb target genes, such as Miniature, and thus facilitate the final morphology of the developing denticle (Fig. 7B). Our genetic data suggest that wild-type Ck provides a buffering mechanism for the incorrect Svb target levels that accumulate in a wg null mutant.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of Ck structure and function. (A) Positions of new ck alleles with respect to functional domains described in Kiehart et al. (Kiehart et al., 2004). (B) Model for Wg-mediated control of denticle shape. Ck distributes Miniature and Forked within the developing denticle and can buffer the excess amounts of Svb targets produced in a wg mutant. In the absence of both wg and ck activity, the excess amounts disrupt denticle elongation.

Wg signaling is most commonly associated with specifying the naked cuticle cell fate, but its other role in generating diverse denticle morphologies allowed us to detect requirements for Ck function in this process. The morphogenesis role requires lower levels of Wg signaling, as evidenced by weak mutations such as wgPE2 that can generate diversity but cannot specify naked cuticle cell fate (Bejsovec and Wieschaus, 1995; Moline et al., 2000). Our finding that levels of svb and its target genes influence denticle morphology suggests that Wg signaling may generate denticle diversity in conjunction with Notch and EGF signaling by producing subtly graded differences in svb expression that are below the limits of current detection methods. Our temperature shift experiments suggest that this is a continuing, independent role for Wg signaling, as it is detected after the point at which Wg input regulates the pattern of Serrate and rhomboid expression. We propose that late Wg signaling helps titrate the synthesis of svb target gene products to optimal levels required for shaping the denticles. The ck mutant provides a sensitized background that may allow further investigation of this possibility. The enhancement of denticle morphology defects along the dorsolateral edges of the denticle field also suggests input from dorsoventral patterning pathways, such as Dpp signaling.

MyosinVIIA in humans is known to play a crucial role in hearing (reviewed by Hasson, 1999; Maniak, 2001; Petit, 2001; Dror and Avraham, 2009). Stereocilia on the hair cells of the inner ear transduce the mechanical stimulation of sound waves into electrical impulses. Stereocilia are stabilized by bundles of actin filaments and microtubules, much like the denticles and bristles that decorate the fly epidermis. Mutations in the human myosinVIIA are associated with Usher syndrome, the most common hereditary deafness/blindness disorder, which results in disorganized stereocilia that cannot transduce sound. The precise role of myosinVIIA in organizing and maintaining these structures is as yet unknown. However, ck mutants in the fly also are deaf, and show morphological changes in the auditory sensory structures (Todi et al., 2005), suggesting that the fly is a powerful model system for exploring this aspect of myosinVIIA function. Indeed, the connection between Ck and Miniature may also be relevant to human hearing disorders. Mutations in α-tectorin, a human protein that shares functional domains with Miniature and organizes extracellular matrix in the cochlea, are associated with hereditary hearing loss (Dror and Avraham, 2009; Plaza et al., 2010).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Kiehart laboratory and to the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks, to the dedicated staff at FlyBase for essential information, and to M. Moline and A. Hofhine for technical assistance in early parts of this work. We also thank L. Eibest for her assistance with ESEM imaging.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01-GM86620 to A.B.] and by the National Science Foundation [IOB-0613328 to A.B.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Akam M. (1987). The molecular basis for metameric pattern in Drosophila embryo. Development 101, 1–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C., Lecourtois M., Vincent J. (1999). Wingless and Hedgehog pattern Drosophila denticle belts by regulating the production of short-range signals. Development 126, 5689–5698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A. (2006). Flying at the head of the pack: Wnt biology in Drosophila. Oncogene 25, 7442–7449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A., Martinez Arias A. (1991). Roles of wingless in patterning the larval epidermis of Drosophila. Development 113, 471–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A., Wieschaus E. (1993). Segment polarity gene interactions modulate epidermal patterning in Drosophila embryos. Development 119, 501–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejsovec A., Wieschaus E. (1995). Signaling activities of the Drosophila wingless gene are separately mutable and appear to be transduced at the cell surface. Genetics 139, 309–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega J. A., Hartenstein V. (1985). The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo R. A., Cox R. T., Moline M. M., Roose J., Polevoy G. A., Clevers H., Peifer M., Bejsovec A. (1998). Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signalling activity. Nature 395, 604–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanut-Delalande H., Fernandes I., Roch F., Payre F., Plaza S. (2006). Shavenbaby couples patterning to epidermal cell shape control. PLoS Biol. 4, e290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A. T., Jones W. M., Bejsovec A. (2007). The HMG-box transcription factor SoxNeuro acts with Tcf to control Wg/Wnt signaling activity. Development 134, 989–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delon I., Chanut-Delalande H., Payre F. (2003). The Ovo/Shavenbaby transcription factor specifies actin remodelling during epidermal differentiation in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 120, 747–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson W. J., Thatcher J. W. (1997). Morphogenesis of denticles and hairs in Drosophila embryos: involvement of actin-associated proteins that also affect adult structures. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 38, 9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilks S. A., DiNardo S. (2010). Non-cell-autonomous control of denticle diversity in the Drosophila embryo. Development 137, 1395–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror A. A., Avraham K. B. (2009). Hearing loss: mechanisms revealed by genetics and cell biology. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 411–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes I., Chanut-Delalande H., Ferrer P., Latapie Y., Waltzer L., Affolter M., Payre F., Plaza S. (2010). Zona pellucida domain proteins remodel the apical compartment for localized cell shape changes. Dev. Cell 18, 64–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson T. (1999). Sensing a function for myosin VIIa. Curr. Biol. 9, R838–R841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R., Gibori G. B., Bejsovec A. (1997). Wingless signaling generates pattern through two distinct mechanisms. Development 124, 3727–3736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk J., DiNardo S., Kostriken R., O’Farrell P. H. (1991). Multiple modes of engrailed regulation in the progression towards cell fate determination. Nature 352, 404–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W. M., Bejsovec A. (2005). RacGap50C negatively regulates Wingless pathway activity during Drosophila embryonic development. Genetics 169, 2075–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehart D. P., Franke J. D., Chee M. K., Montague R. A., Chen T. L., Roote J., Ashburner M. (2004). Drosophila crinkled, mutations of which disrupt morphogenesis and cause lethality, encodes fly myosin VIIA. Genetics 168, 1337–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniak M. (2001). Cell adhesion: ushering in a new understanding of myosin VII. Curr. Biol. 11, R315–R317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arias A. (1993). Development and patterning of the larval epidermis of Drosophila. in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; [Google Scholar]

- Moline M. M., Dierick H. A., Southern C., Bejsovec A. (2000). Non-equivalent roles of Drosophila Frizzled and Dfrizzled2 in embryonic Wingless signal transduction. Curr. Biol. 10, 1127–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer J., Johnston P., Rijsewijk F., Nusse R., Lawrence P. A. (1992). The consequences of ubiquitous expression of the wingless gene in the Drosophila embryo. Development 116, 711–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsslein-Volhard C., Wieschaus E., Kluding H. (1984). Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster: I. Zygotic loci on the second chromosome. Wilhelm Roux’s Archives Dev. Biol. 193, 267–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai L. M., Orsulic S., Bejsovec A., Peifer M. (1997). Negative regulation of Armadillo, a Wingless effector in Drosophila. Development 124, 2255–2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payre F., Vincent A., Carreno S. (1999). ovo/svb integrates Wingless and DER pathways to control epidermis differentiation. Nature 400, 271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit C. (2001). Usher syndrome: from genetics to pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2, 271–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza S., Chanut-Delalande H., Fernandes I., Wassarman P. M., Payre F. (2010). From A to Z: apical structures and zona pellucida-domain proteins. Trends Cell. Biol. 20, 524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. H., Roberts D. M., McCartney B. M., Jezuit E., Peifer M. (2006). Cytoskeletal dynamics and cell signaling during planar polarity establishment in the Drosophila embryonic denticle. J. Cell Sci. 119, 403–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roch F., Alonso C. R., Akam M. (2003). Drosophila miniature and dusky encode ZP proteins required for cytoskeletal reorganisation during wing morphogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1199–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todi S. V., Franke J. D., Kiehart D. P., Eberl D. F. (2005). Myosin VIIA defects, which underlie the Usher 1B syndrome in humans, lead to deafness in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 15, 862–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie S., Ashburner M., Falls K., Leyland P., McQuilton P., Marygold S., Millburn G., Osumi-Sutherland D., Schroeder A., Seal R., et al. (2009). FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila Gene Ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D555–D559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiellette E. L., McGinnis W. (1999). Hox genes differentially regulate Serrate to generate segment-specific structures. Development 126, 1985–1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E., Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1986). Looking at embryos. In Drosophila, A Practical Approach (ed. Roberts D. B.). Oxford, UK: IRL Press; [Google Scholar]