SUMMARY

Adrenergic stimulation of the heart engages cAMP and phosphoinositide second messenger signaling cascades. Cardiac phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110γ participates in these processes by sustaining β-adrenergic receptor internalization through its catalytic function and by controlling phosphodiesterase 3B (PDE3B) activity via an unknown kinase-independent mechanism. We have discovered that p110γ anchors protein kinase A (PKA) through a site in its N-terminal region. Anchored PKA activates PDE3B to enhance cAMP degradation and phosphorylates p110γ to inhibit PIP3 production. This provides local feedback control of PIP3 and cAMP signaling events. In congestive heart failure, p110γ is upregulated and escapes PKA-mediated inhibition, contributing to a reduction in β-adrenergic receptor density. Pharmacological inhibition of p110γ normalizes β-adrenergic receptor density and improves contractility in failing hearts.

INTRODUCTION

In cardiomyocytes, stimulation of G protein-coupled β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) by catecholamines engages tandem signaling pathways that utilize the second messengers cyclic AMP (cAMP) and phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 or PIP3) (Rockman et al., 2002). cAMP is generated upon engagement of β-AR/Gs-triggered stimulation of adenylyl cyclase, thus leading to the activation of protein kinase A (PKA), which in turn controls myocardial contractility (Xiang and Kobilka, 2003). Instead, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is produced from PtdIns(4,5)P2 by the main G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks), PI3Kβ and γ (Guillermet-Guibert et al., 2008; Hirsch et al., 2000).

Signals processed through myocardial cAMP/PKA and PI3Kγ/PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 pathways are tightly coupled, thus generating intracellular sites for crosstalk between the cAMP and PtdIns (3,4,5)P3 responsive enzymes. For instance, PI3Kγ cooperates with β-ARK1 to dampen cAMP signaling by promoting desensitization and downregulation of β-ARs (Naga Prasad et al., 2001). Additionally, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is needed for AP-2 adaptor recruitment at the plasma membrane and for the consequent organization of clathrin-coated pits (Naga Prasad et al., 2002). This mechanism contributes to the pathological decrease in myocardial β-AR density and function during the natural history of heart failure (Bristow et al., 1982; Nienaber et al., 2003; Perrino et al., 2007). PI3Kγ also attenuates the cAMP/PKA pathway by working as an activator of the phosphodiesterases PDE3B and PDE4, which hydrolyze cAMP to 5′-AMP (Conti and Beavo, 2007; Kerfant et al., 2007; Patrucco et al., 2004). Although little is known about the regulation of PDE3B by PI3Kγ, previous reports have demonstrated that this is operated within a macro-molecular complex including both the catalytic (p110γ) and the adaptor (p84/87) subunits of PI3Kγ (Patrucco et al., 2004; Voigt et al., 2006). Importantly, the functional interaction between p110γ and PDE3B does not involve the kinase activity of p110γ, which instead acts as a scaffold for PDE3B (Hirsch et al., 2009). As a result, mice lacking p110γ exhibit decreased myocardial PDE3B activity and elevated cAMP, while PDE3B function and cAMP levels are normal in mice expressing a kinase-inactive p110γ. In p110γ null mice subjected to cardiac pressure overload and not in mice expressing a kinase-dead p110γ, cAMP rises uncontrolled, thus leading to cardiomyopathy and heart failure (Crackower et al., 2002; Patrucco et al., 2004).

Therefore, p110γ might constitute a molecular hub connecting the cAMP and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 signaling axes in cardiomyocytes. However, the molecular mechanisms operating this interplay remain unclear. We show herein that crosstalk between myocardial cAMP and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 signaling pathways is mediated by the formation of a previously unidentified multiprotein complex that couples p110γ to PDE3B activation. Within this complex, p110γ acts as an A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) tethering the phosphodiesterase near its activator, PKA. Functional studies further confirm that anchoring of PKA to p110γ inhibits its lipid kinase activity in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Coupling of cAMP and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 signaling mediated by the anchoring function of p110γ is perturbed in mouse models of congestive heart failure, leading to β-AR downregulation. Inhibition of p110γ can restore compromised β-AR density and improve contractility, highlighting the potential for therapeutic interventions.

RESULTS

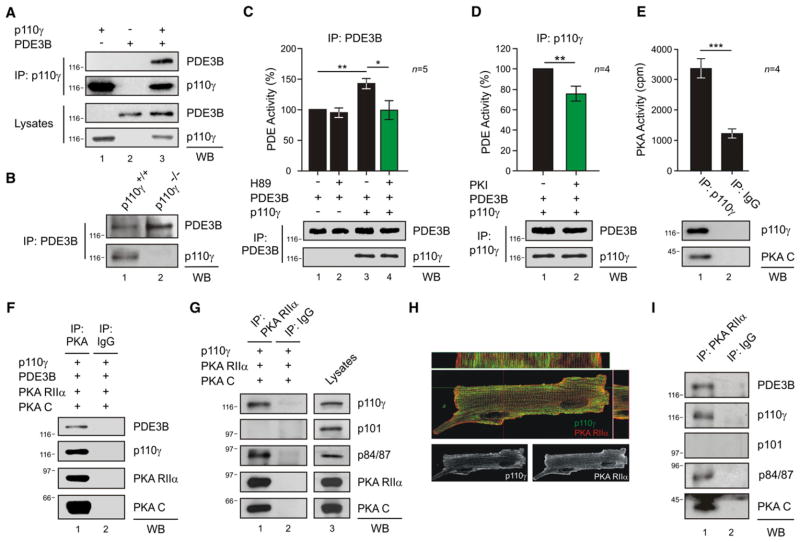

p110γ Activates PDE3B in a PKA-Dependent Manner

To elucidate the mechanisms linking PDE3B activity to p110γ, these proteins were overexpressed in HEK293T cells. p110γ and PDE3B could be coimmunoprecipitated in this cell type as in mouse cardiomyocytes (Figures 1A, lane 3, and 1B, lane 1). The cotransfection of p110γ wild-type or p110γ kinase-dead with PDE3B resulted in a higher phosphodiesterase activity than in cells expressing PDE3B alone (Figures 1C, column 3, and S1A). This confirmed that p110γ activates PDE3B in a kinase-independent manner. One interpretation was that p110γ may associate with an activator of PDE3B, and PKA appeared as a likely candidate (Degerman et al., 1998). Indeed, recombinant PKA phosphorylated PDE3B in vitro (Figure S1B). Furthermore, cAMP/PKA-mediated phosphorylation of PDE3B was enhanced in the presence of p110γ (Figure S1C). Treatment with PKA inhibitors H89 or PKI blunted the increase in PDE3B-mediated cAMP hydrolysis (Figures 1C, column 4, and 1D, column 2). Taken together, our results imply that PKA residing in the p110γ-PDE3B complex enhances the activity of PDE3B. Further support for this model was provided by evidence that p110γ copurified with PKA activity (Figure 1E, column 1). Additional experiments demonstrated the copurification of p110γ and PDE3B with the regulatory (RIIα) and catalytic (C) subunits of PKA (Figure 1F, lane 1). In contrast, other class I PI3Ks expressed in the heart, p110α and p110β, did not associate with PKA and PDE3B (Figures S1D and S1E). Interestingly, p110γ was found to associate with the PKA regulatory subunit RIIα but not with the RIα isoform (Figure S1F). In this complex, we could also detect the p110γ regulatory subunit p84/87, but not p101 (Figure 1G, lane 1).

Figure 1. p110γ Activates PDE3B through PKA within a PI3Kγ-PKA-PDE3B Complex.

(A) Coimmunoprecipitation of PDE3B with p110γ in HEK293T cells transfected with p110γ and PDE3B-Flag.

(B) Coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ with PDE3B in wild-type (p110γ+/+) but not in p110γ knockout (p110γ−/−) mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes.

(C) Phosphodiesterase activity in PDE3B immunoprecipitates upon transfection of HEK293T cells with PDE3B-Flag (PDE3B) or with PDE3B-Flag and p110γ. Cells were treated with PKA inhibitor H89 (5 μM, 10 min) or vehicle as indicated. PDE activity (%) was calculated relative to the activity of single PDE3B transfectants.

(D) Phosphodiesterase activity (%) of double p110γ, PDE3B-Flag transfectants treated with PKA inhibitor Myr-PKI (5 u;M, 10 min) or vehicle.

(E) PKA activity (cpm) in a p110γ immunoprecipitate from transfected HEK293T cells.

(F) Coimmunoprecipitation of transfected p110γ, PDE3B-Flag, PKA RIIα-ECFP (PKA RIIα), and PKA CAT-YFP (PKA C) from HEK293T extracts.

(G) Coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ and p84/p87, but not p101, with PKA RIIα from HEK293T transfected cells.

(H) Colocalization (yellow spots) of p110γ (green) and PKA RIIα (red) by immunofluorescence in mouse adult cardiomyocytes. Longitudinal and transverse sections are shown in the upper and right panels, respectively. Single p110γ and PKA RIIα localizations are presented in the lower panels.

(I) PDE3B, p110γ, p84/p87, and PKA CAT (PKA C), but not p101, coimmunoprecipitate with PKA RIIα in myocardial tissue extracts of wild-type mice. A representative immunoprecipitation is presented in (A)–(G) and (I). For all bar graphs, values represent mean ± SEM of a minimum of four independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figures S1 and S2.

Further characterization of the p110γ-PKA complex was conducted in the mouse heart. Coimmunoprecipitation confirmed the interaction of p110γ with PKA in the myocardium Figures (S2A and S2B). Immunofluorescence staining further illustrated that p110γ, RIIα, and PDE3B signals overlapped in mouse adult cardiomyocytes (Figures 1H, S2C, and S2D). More stringent biochemical analyses showed that, in myocardial lysates, RIIα coimmunoprecipitates with PDE3B, the catalytic subunit of PKA, as well as the p110γ and p84/87 subunits of PI3Kγ (Figure 1I, lane 1). Additional control experiments established that the p101 subunit of PI3Kγ was not present in this signaling complex. These results establish p110γ as the key element in a PI3Kγ/PDE3B/PKA ternary complex controlling PDE3B activity through PKA.

p110γ Acts as an A-Kinase Anchoring Protein

A critical role for p110γ as a scaffold protein in the complex suggests that p110γ could act as an AKAP. AKAPs directly bind the regulatory subunits of PKA to orchestrate the compartmentalization of cAMP/PKA signaling through association with target effectors, substrates, and signal terminators (Carr et al., 1991; Scott and Pawson, 2009). Accordingly, recombinant RIIα subunits of PKA copurified with recombinant p110γ in an in vitro pull-down experiment (Figure 2A, lane 1). Further support for this interaction was provided by surface plasmon resonance measurements, which calculated a dissociation constant (KD) of 1.86 ± 0.01 μM for the interaction of p110γ with RIIα (Figure 2B). RII overlay experiments detected a binding band of 116 kDa in p110γ immunoprecipitates (Figure 2C, lane 1, upper panel). This RII-binding band was absent in control blots pretreated with the PKA anchoring inhibitor peptide, AKAP-IS (Figure 2C, lane 1, lower panel). Immunoblot analysis of PKA RIIα immuno-precipitates established that treatment with AKAP-IS could disrupt the RIIα-p110γ interaction (Figures 2D, lane 2, and 2E, column 2). Control experiments indicated that other AKAPs expressed in cardiomyocytes, including AKAP18α, AKAP79, and AKAP-Lbc, do not coimmunoprecipitate with p110γ (Figures S3A–S3C). Mapping studies have revealed that residues 1–45 of RIIα form a docking and dimerization domain that serves as a binding surface for AKAPs (Gold et al., 2006; Hausken et al., 1994). RIIα fragments lacking this region (PKA RIIα Δ1–45) did not bind p110γ, as assessed by coprecipitation (Figure 2F, lane 2), indicating that the N terminus of PKA RIIα is essential for the interaction with p110γ. Collectively, these results show that p110γ is a bona fide AKAP.

Figure 2. p110γ Is a Bona Fide AKAP.

(A) In vitro copurification of p110γ-GST and PKA RIIα-6His in a GST pull-down assay.

(B) Direct interaction of p110γ and PKA RIIα in a surface plasmon resonance assay. p110γ was immobilized on the chip, and PKA RIIα was injected at three different concentrations.

(C) Binding of 32P-labeled PKA RIIα to immunoprecipitated p110γ in the presence of AKAP-IS scrambled peptide but not in the presence of AKAP-IS peptide.

(D) Competition of the p110γ-PKA RIIα coimmunoprecipitation with AKAP-IS peptide.

(E) Quantitative densitometry of the competition experiment represented in (D). Values represent mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. *p < 0.05.

(F) Loss of the coimmunoprecipitation of PKA RIIα with p110γ by truncation of the 1–45 amino acids of RIIα-ECFP (PKA RIIα Δ1–45). A representative assay is presented in all figures. See also Figure S3.

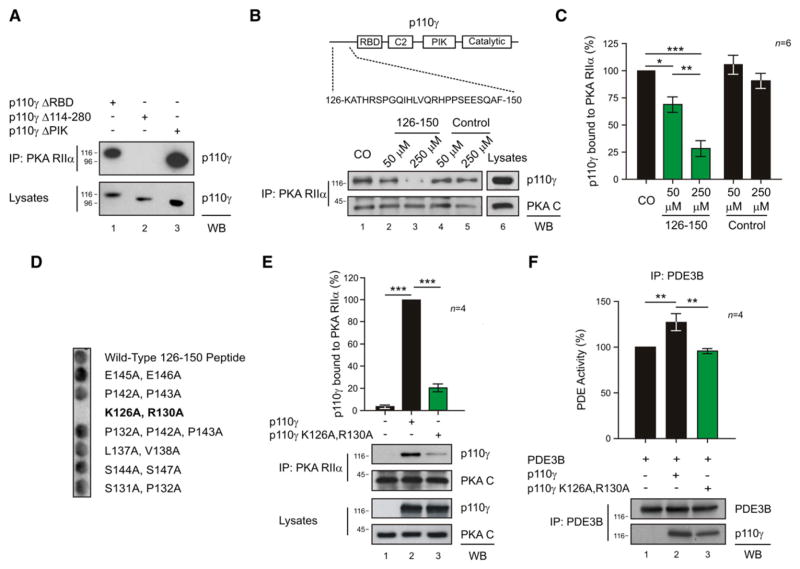

Mapping of the p110γ-PKA RIIα Interaction

Mapping studies in HEK293T cells using a series of p110γ deletion fragments (Figure S4A) revealed that RIIα interacts with an amino-terminal portion of p110γ spanning residues 114–280 (Figure 3A, lane 2). Further investigation with a solid-phase peptide array located the RIIα binding determinants between residues 126 and 150 of p110γ (Figure S4B). These results were independently confirmed when a peptide encompassing these residues of p110γ selectively disrupted the RIIα-p110γ interaction in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 3B, lanes 2 and 3, and 3C, columns 2 and 3). Importantly, loss of PKA anchoring led to a concomitant decrease in p110γ-associated PDE3B activity (Figure S4C).

Figure 3. Mapping of the p110γ-PKA RIIα Interaction.

(A) Loss of the coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ-Myc with PKA RIIα by deletion of amino acids 114–280 (p110γ Δ 114–280) but not by deletion of the Ras-binding domain (p110γ Δ RBD) or the PIK domain (p110γ Δ PIK) of p110γ-Myc.

(B) Sequence of the 126–150 peptide is represented on a scheme of p110γ. In dose-dependent competition experiments, the 126–150 peptide, but not a scrambled control peptide, antagonized the p110γ-RIIα protein-protein interaction.

(C) Quantitative densitometry of the competition experiment represented in (B).

(D) Binding of PKA RIIα to a set of alanine mutant 126–150 p110γ peptides in a solid-phase peptide array.

(E) Mutation of K126 and R130 of p110γ to A (p110γ K126A, R130A) blunts coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ with PKA RIIα in transfected HEK293T cells. Values were obtained by quantitative densitometry and normalized over control.

(F) Phosphodiesterase activity (%) of PDE3B immunoprecipitates upon transfection of HEK293T cells with PDE3B-Flag alone or with PDE3B-Flag and either wild-type or mutant p110γ (p110γ K126A, R130A). A representative immunoprecipitation is provided for (A), (B), (E), and (F). For all bar graphs, values represent mean ± SEM of a minimum of four independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figure S4.

More definitive analysis of the p110γ 126–150 peptide revealed that N-terminal residues are required for the binding to PKA RIIα (Figure S4D). In addition, spot array analysis of C-terminal truncations indicated that the exposure of charged or hydrophobic residues flanking this region blunted the binding to RIIα (Figure S4E). Alanine scanning of this region suggested that while single point mutations did not disrupt the binding (data not shown), the substitution of basic residues 126 (K) and 130 (R) with A abolished the interaction with RIIα (Figure 3D). Cell-based analyses confirmed that a p110γ K126A, R130A mutant exhibited a reduced ability to copurify with the PKA holo-enzyme (Figure 3E, lane 3). Moreover, this PKA-anchoring defective p110γ mutant failed to increase PDE3B activity (Figures 3F, column 3 and S4F). Thus, association of PKA with p110γ allows PKA to modulate PDE3B activity, thereby suppressing local accumulation of cAMP.

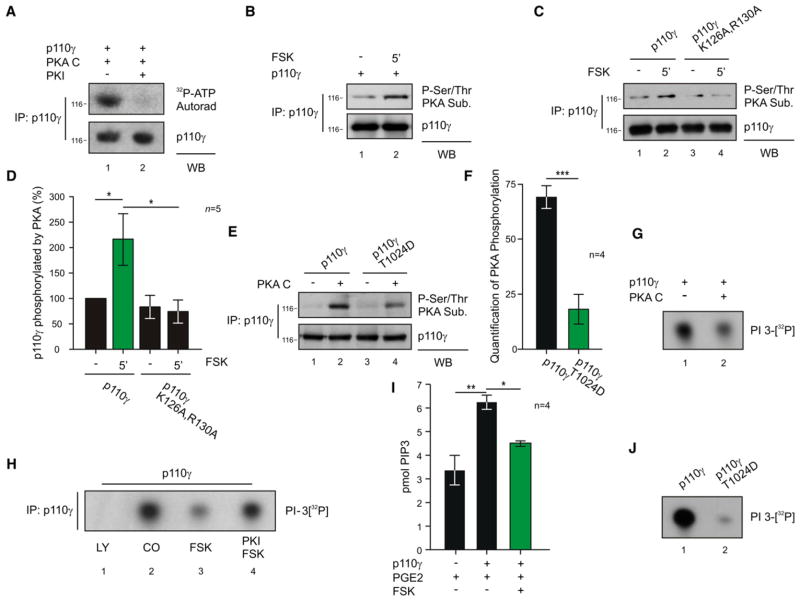

PKA Phosphorylates p110γ and Inhibits p110γ Lipid Kinase Activity

We further reasoned that anchored PKA might phosphorylate p110γ to modulate its catalytic activity. Indeed, recombinant PKA mediated the incorporation of 32P into p110γ, and this effect was blocked in the presence of the specific PKA inhibitor peptide PKI (Figures 4A and S5A). Studies in cultured cells indicated that the forskolin-evoked accumulation of intracellular cAMP induced the phosphorylation of p110γ by PKA (Figure 4B, lane 2). Conversely, PKA failed to phosphorylate the p110γ K126A, R130A mutant that does not bind PKA RIIα (Figures 4C, lane 4 and 4D, column 4). We then proceeded to identify the PKA phosphorylation site on p110γ using sequential bioinformatic, biochemical, and functional approaches. Bioinformatic screening of the p110γ sequence indentified a number of putative PKA phosphorylation sites (Table S1). However, only two of them (S400 and T1024) (1) appeared conserved among different species and (2) contained an R side chain at the −3 position, which is optimal for PKA substrate recognition (Figure S5B). Peptides containing these residues were not covered in a phosphoproteomic analysis, but peptide arrays of p110γ phosphorylated by PKA showed a signal in two overlapping peptides containing T1024 but not in sequences containing S400 (Figure S5C). Most relevantly, only the T1024D and the T1024A mutations, but not S400A, resulted in a significant decrease in the phosphorylation of p110γ by PKA (Figures 4E, lane 4, 4F, column 2, and S5D), indicating that T1024 represents the main phosphorylation site of p110γ by PKA. It is worthy to note that the T1024 is conserved in p110γ orthologs and is not present in the other class I PI3Ks (Figure S5E).

Figure 4. PKA Phosphorylates and Inhibits p110γ.

(A) Phosphorylation of p110γ immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293T cells in the presence of recombinant PKA C, 32P-ATP, and PKA inhibitor PKI (1 μM) or vehicle.

(B) PKA-mediated phosphorylation of p110γ immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells upon stimulation with forskolin (FSK 20 μM, 5 min).

(C) PKA-mediated phosphorylation of p110γ or p110γ K126A, R130A immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells upon stimulation with forskolin (FSK 20 μM, 5 min).

(D) Quantitative densitometry of the experiment represented in (C).

(E) PKA-mediated phosphorylation of p110γ or p110γ T1024D mutant immunoprecipitated from HEK293T cells and incubated or not with active PKA (30 min).

(F) Quantitative densitometry of PKA phosphorylation (background subtracted) of the experiment represented in (E).

(G) Lipid kinase activity of recombinant p110γ-GST incubated in vitro with or without recombinant PKA C (30 min).

(H) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293T cells treated with vehicle, pan-p110 inhibitor LY-294002 (LY, 20 μM, 15 min), forskolin (FSK, 20 μM, 5 min) or FSK plus PKA inhibitor Myr-PKI (1 μM).

(I) Measurement of cellular PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (pmol PIP3) levels in transfected HEK293T treated with the GPCR agonist PGE2 (100 nM, 10 min) alone or in combination with FSK (50 μM, 3 min).

(J) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ wild-type or p110γ T1024D mutant immunoprecipitated from transfected HEK293T cells. In lipid kinase assays (G, H, J), the ability of p110γ to phosphorylate phosphoinositide was detected by autoradiography following incubation with 32P-ATP substrate. A representative assay is presented in all figures. For all bar graphs, values represent mean ± SEM of a minimum of four independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figures S5 and S6.

Lipid kinase assays showed that the incubation of PKA with recombinant p110γ reduced the kinase activity of p110γ on both PtdIns and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Figures 4G, lane 2, and S6A). Yet treatment with the PKI peptide abolished this effect (Figure S6B), thus demonstrating that PKA negatively regulates the lipid kinase activity of p110γ. Similarly, cell-based studies demonstrated that forskolin-dependent activation of PKA resulted in a decrease in p110γ lipid kinase activity, which was blocked by PKI (Figure 4H, lanes 3 and 4). Forskolin treatment also significantly reduced, by 28.9%, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production in cells stimulated with PGE2, a G protein-coupled receptor agonist activating p110γ (Figure 4I, column 3). Collectively, these observations establish that PKA inhibits p110γ through direct phosphorylation. Of note, the phosphomimetic T1024D mutant showed reduced lipid kinase activity compared to wild-type p110γ (Figure 4J, lane 2), indicating that the phosphorylation of p110γ by PKA on T1024 represents a crucial mechanism controlling p110γ lipid kinase activity.

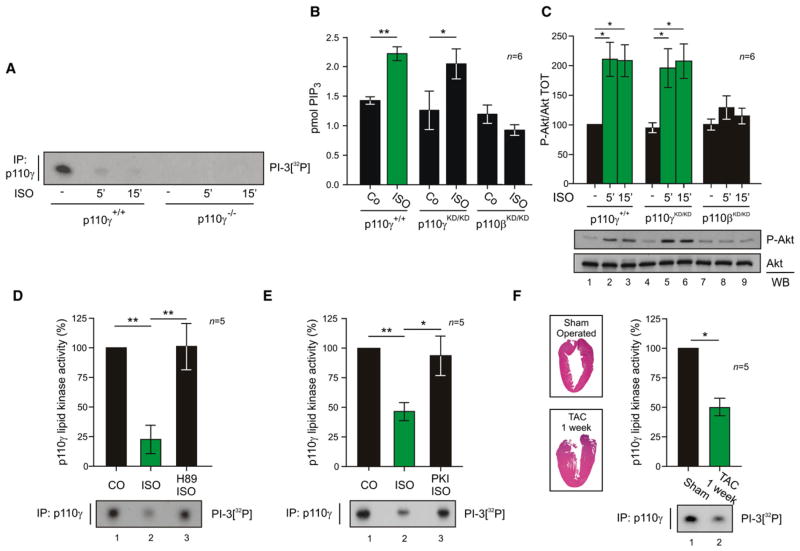

p110γ Is Inhibited by PKA in Cardiomyocytes

Next, the functional interaction between p110γ and PKA was explored in vivo. Wild-type mouse hearts stimulated with β-AR agonist isoproterenol, which triggers the PKA axis, showed a rapid inhibition of the lipid kinase activity of p110γ (Figure 5A). Although this is apparently in contrast with the notion that β-AR activation triggers the PI3K/Akt pathway (Jo et al., 2002; Leblais et al., 2004), isoproterenol induced PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 rise and Akt phosphorylation in p110γ kinase-dead mice (Figures 5B, columns 3 and 4, and 5C, columns 4–6). Adrenergic-evoked response was instead lost in p110β kinase-dead mice (Figures 5B, columns 5 and 6, and 5C, columns 7–9), supporting the view that only p110γ activity is repressed upon β-AR activation. The inhibition of p110γ was further confirmed in ex vivo Langendorff perfused hearts, where isoproterenol blunted p110γ activity by 77.3% ± 12%, while coperfusion with the PKA inhibitor H89 left p110γ activity unchanged compared to control hearts (Figure 5D, lanes 2 and 3). Moreover, in isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes, isoproterenol reduced the lipid kinase activity of p110γ by 53.3% ± 7% (Figure 5E, lane 2). Inhibition of PKA with PKI restored p110γ activity (Figure 5E, lane 3). We then investigated the in vivo regulation of p110γ activity by PKA in a mouse model of cardiac pressure overload characterized by endogenous adrenergic stimulation of the myocardium as well as compensatory hypertrophy (Figure 5F, insets). After 1 week of transverse aortic constriction (TAC), the p110γ lipid kinase activity was markedly reduced, by 50% ± 7%, when compared to sham-operated mice (Figure 5F, lane 2). Taken together, these findings show that signaling by the β-AR/cAMP/PKA pathway inhibits cardiac p110γ.

Figure 5. PKA Inhibits the Lipid Kinase Activity of p110γ in the Myocardium.

(A) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from myocardial tissue lysates following treatment of wild-type (p110γ+/+) or p110γ knockout mice (p110γ−/−) with β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO, 1.25 mg/kg i.p. for 5 or 15 min) or vehicle.

(B) Measurement of myocardial PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (pmol PIP3) levels in wild-type (p110γ+/+), p110γ kinase-dead (p110γKD/KD), and p110β kinase-dead (p110βKD/KD) mice treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 1.25 mg/kg i.p. for 5 min) or vehicle.

(C) Phospho-Akt (P-Akt) and total Akt (Akt) levels in myocardial tissue lysates following treatment of wild-type (p110γ+/+), p110γ kinase-dead (p110γKD/KD), and p110β kinase-dead (p110βKD/KD) mice with β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO, 1.25 mg/kg i.p. for 5 or 15 min) or vehicle.

(D) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from myocardial tissue lysates following ex vivo cardiac Langendorff perfusion (5 min) with vehicle, isoproterenol (ISO 10 μM), or ISO plus PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μM).

(E) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from rat adult cardiomyocytes treated with isoproterenol (ISO, 1 μM, 3 min), ISO plus PKA inhibitor Myr-PKI (1 μM, 5 min), or vehicle.

(F) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from myocardial tissue lysates of mice subjected to transverse aortic constriction for 1 week (TAC 1 week) or to sham operation. Insets are representative hematoxylin and eosin stainings of left ventricular sections from sham-operated and 1 week TAC mice. A representative assay is presented in all figures. For all bar graphs, values, obtained by quantitative densitometry and normalized over control, represent mean ± SEM of a minimum of five mice per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Regulation of p110γ Kinase Activity by PKA Impacts on β-Adrenergic Density

The kinase activity of p110γ is known to reduce myocardial β-AR density (Nienaber et al., 2003; Perrino et al., 2007). We thus hypothesized that the regulation of p110γ by PKA could contribute to this process by mediating a feedback loop controlling β-AR cell surface expression. Therefore, β-AR density was measured in wild-type, p110β kinase-dead (p110βKD/KD), p110γ knockout (p110γ−/−), and p110γ kinase-dead (p110γKD/KD) hearts. The loss of p110γ but not of p110β activity was associated with a significant increase in β-AR density (p110γ−/− + 36.4% and p110γKD/KD + 25.8% versus wild-type controls) (Figure 6A, columns 3 and 4). Similarly, treatment of wild-type mice with a selective p110γ inhibitor (AS605240) determined a significant 28.1% upregulation of cardiac β-AR density, while AS605240 did not modify β-AR density in p110γKD/KD hearts, indicating that this compound is specific for p110γ (Figure S7A).

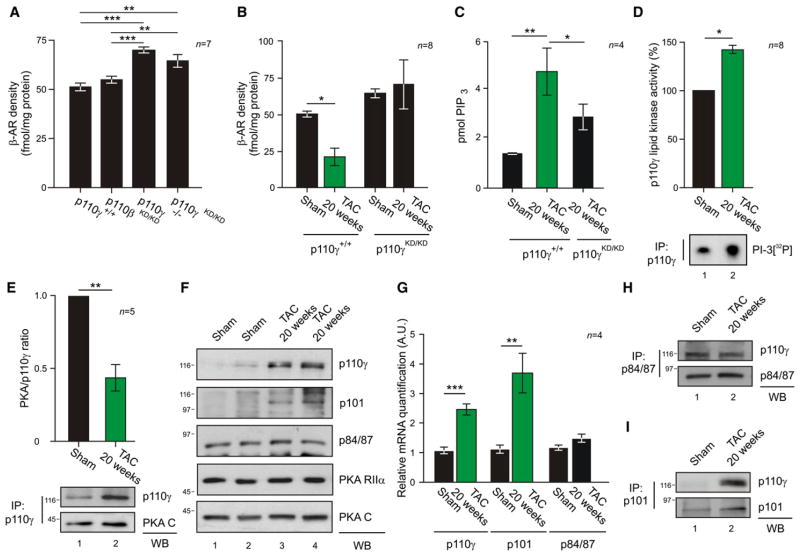

Figure 6. Modulation of p110γ Lipid Kinase Activity by PKA Affects β-AR Density.

(A) Myocardial β-AR density in wild-type (p110γ+/+), p110β kinase-dead (p110βKD/KD), p110γ knockout (p110γ−/−), and p110γ kinase-dead (p110γKD/KD) mice.

(B) Myocardial β-AR density of p110γ+/+ and p110γKD/KD mice subjected to sham operation or to aortic constriction for 20 weeks (TAC 20 weeks).

(C) Myocardial PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (pmol PIP3) levels in hearts obtained from sham-operated mice or from 20 week TAC-treated wild-type or p110γKD/KD mice.

(D) Lipid kinase activity of p110γ immunoprecipitated from myocardial tissue lysates of sham-operated or 20 week TAC-treated mice. Values were obtained by quantitative densitometry and normalized over control.

(E) Coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ and PKA C from myocardial lysates from mice subjected to pressure overload for 20 weeks or to sham operation. After quantitative densitometry, p110γ-bound PKA was expressed as the ratio of coimmunoprecipitated PKA C over immunoprecipitated p110γ.

(F) Total levels of the indicated proteins in myocardial tissue lysates from sham-operated mice or from mice subjected to pressure overload for 20 weeks.

(G) mRNA levels of p110γ, p101, and p84/p87 in hearts from sham-operated mice or mice subjected to 20 weeks of TAC.

(H) Coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ with p84/87 from myocardial lysates of mice subjected to pressure overload for 20 weeks or to sham operation.

(I) Coimmunoprecipitation of p110γ with p101 from myocardial lysates of mice subjected to pressure overload for 20 weeks or to sham operation. In β-AR density measurements (A and B), receptor density is expressed as the Bmax after saturation binding using 125I-labeled cyanopindolol ligand (fmol/mg protein). A representative assay is presented in (D)–(I). For all bar graphs, values represent mean ± SEM of a minimum of four independent experiments or six mice per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. See also Figure S7.

A reduction of cell surface β-ARs is a key trait of heart failure (Bristow et al., 1982, 1990; Denniss et al., 1989; Engelhardt et al., 1996). This prompted us to investigate whether abnormal regulation of p110γ activity might be involved in this pathological condition. We thus examined β-AR surface expression and p110γ lipid kinase activity in hearts isolated from mice after 20 weeks of TAC, a time sufficient to develop a hypokinetic dilative cardiomyopathy (left ventricle fractional shortening <30%). At this stage, wild-type animals presented a 58.4% reduction in β-AR density compared to sham controls (Figure 6B, column 2). In contrast, β-AR membrane density remained normal when p110γKD/KD mice were subjected to 20 weeks of aortic banding (Figure 6B, column 4). This indicated that p110γ stimulates β-AR downregulation in the myocardium. Since PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is critical in this process (Naga Prasad et al., 2001), PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels were measured after 20 week TAC. In p110γKD/KD hearts, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 was 39% lower than in wild-types (Figure 6C, column 3). This paralleled a 37.5% ± 6% increase in p110γ activity in 20 week TAC-treated wild-type mice compared to sham (Figure 6D, lane 2). These data suggested that, during heart failure, p110γ-dependent PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 might become independent from PKA-mediated restrain. Consistently, after 20 weeks of TAC, p110γ levels rose significantly while PKA RIIα and PKA C expression remained unaltered (Figure 6E and 6F). Furthermore, proportionally less PKA copurified with p110γ isolated from these hearts (Figure 6E, column 2). Ratio of densitometry of p110γ and the coimmunoprecipitated PKA C from the same blots showed that exposure to prolonged pressure overload evoked a 56.4% ± 9% decrease in the detection of PKA catalytic subunit anchored to p110γ (Figure 6E, column 2). This was further supported by the finding that, during heart failure, expression of PI3Kγ adaptor subunits is altered. While p84/87 remained constant, p101, the adaptor excluded from the PKA-containing complex, followed p110γ upregulation at both mRNA and protein level (Figures 6F, S7B, and 6G). As a consequence of this modulation, the association of p110γ with p84/87 did not change (Figures 6H, lane 2, and S7C). In contrast, p110γ association with p101 significantly increased in failing hearts (Figure 6I, lane 2), resulting in an unphysiological balance between p110γ and its adaptors. Thus, the functional consequence of this pathological reorganization of PI3Kγ subunits is to override cAMP responsive suppression of p110γ lipid kinase activity.

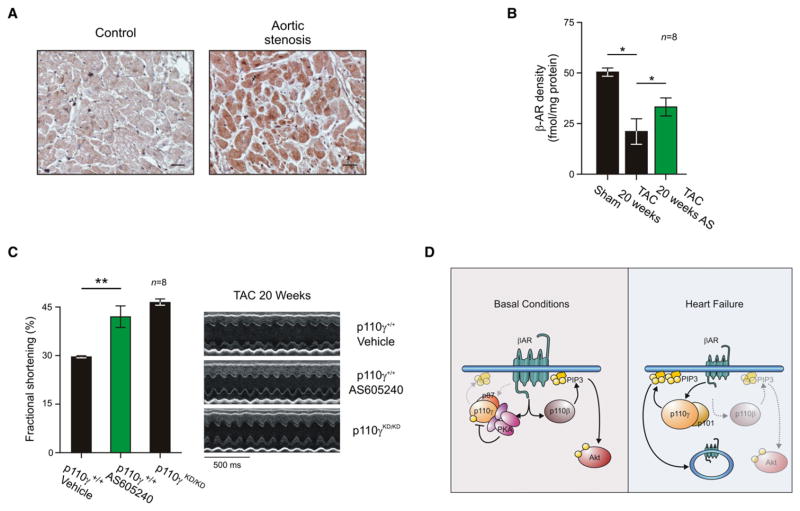

Inhibition of p110γ Kinase Activity Improves Cardiac Function in Heart Failure

Patients with severe aortic stenosis, similar to mice subjected to TAC, showed an increase in p110γ protein expression (Figure 7A, right panel, and Table S2). This is in line with a previous study conducted on patients with end-stage heart failure (Perrino et al., 2007). We thus hypothesized that the development of heart failure involves the aberrant activation of p110γ. We tested this model by treating aortic banded mice with failing hearts (fractional shortening <30%) for 1 week with the selective p110γ inhibitor AS605240. Indeed, AS605240 restored a significant proportion of myocardial β-ARs on the plasma membrane (37.2%) when compared to vehicle-treated controls (Figure 7B, column 3). Accordingly, echocardiographic measurements detected a significant increase (27.7%) in left ventricular fractional shortening after treatment with AS605240 (Figures 7C, column 2, and S7D and Table S3). The p110γ inhibitor restored fractional shortening to that of p110γKD/KD mice subjected to 20 weeks of aortic banding (Figure 7C, column 3). These findings indicate that the pharmacological inhibition of p110γ counteracts the reduction in β-AR density in failing hearts, thus preserving physiological adrenergic signaling and protecting the myocardium from the deterioration of the systolic function in heart failure.

Figure 7. p110γ Inhibition Restores β-AR Density and Cardiac Function in Heart Failure.

(A) Immunohistochemistry for p110γ in human hearts from healthy control patients or patients with aortic stenosis. Bar graph is 25 μm. Representative images are presented.

(B) Myocardial β-AR density of wild-type mice with heart failure (obtained by 20 weeks of pressure overload) treated with selective p110γ inhibitor AS605240 (AS 10 mg/kg i.p. q.d. for 1 week) or vehicle.

(C) Left ventricular fractional shortening of wild-type mice with heart failure treated with AS605240 (10 mg/kg i.p. q.d. for 1 week) or vehicle or of p110γKD/KD mice subjected to aortic constriction for 20 weeks. Representative M-mode echocardiographic snapshots are presented (right). For all bar graphs, values represent mean ± SEM of eight mice per group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(D) Schematic representation of the diverse function of p110γ and p110β in cardiac physiology and pathology. See also Figure S7.

DISCUSSION

Our results establish that myocardial p110γ physically and functionally interacts with PKA. We provide evidence that p110γ orchestrates a physiological crosstalk between cAMP and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 pathways, modulating PDE3B activity and β-AR internalization. In heart failure, this functional coupling operated by p110γ is perturbed, leading to impaired contractility.

While we previously reported that the loss of p110γ results in a defective activity of PDE3B (Patrucco et al., 2004), the molecular mechanism of p110γ-dependent regulation of PDE3B has remained elusive. We now establish that p110γ directly binds PKA, a recognized activator of PDE3B, and that the phosphorylation of PDE3B by PKA is favored when both the kinase and the phosphodiesterase are tethered to p110γ. Whereas the association of p110γ with PKA is direct, the interaction with PDE3B is mediated by the p84/87 PI3Kγ regulatory subunit (Voigt et al., 2006). This supports the selective involvement of p84/87, and not of p101, in constraining the assembly of this ternary complex.

A broader implication of our results is that multiprotein assemblies involving p84/87/p110γ, PDE3B, and PKA coordinate the spatial and temporal modulation of cAMP signaling in the myocardium, acting in a manner similar to other AKAPs such as mAKAP, AKAP350, and gravin (Dodge et al., 2001; Taskén et al., 2001; Willoughby et al., 2006). These signaling complexes tether PKA in proximity to PDEs to locally modulate cAMP signaling, thereby optimizing signal termination. In respect to what has been shown for other AKAPs, an important finding of the present study is that we provide evidence of the colocalization of PKA and PDE3B in a macromolecular complex. By interacting with PKA and PDE3B, the p84/87/p110γ heterodimer appears involved in a crucial negative feedback controlling the cAMP pathway. In p110γ-deficient animals, loss of this feedback leads to cAMP accumulation in resting conditions (Crackower et al., 2002) and to cAMP-mediated cardiac damage under stress (Patrucco et al., 2004).

While p110γ appears to behave like an AKAP in that it directly binds the RIIα subunit, its PKA-anchoring site appears to be atypical. Classical AKAPs bind to PKA RIIα through a conserved amphipathic helix (Carr et al., 1991), and their association can be disrupted by synthetic peptides designed to reproduce this helical structure (Alto et al., 2003; Gold et al., 2006). As expected, the p110γ/PKA RIIα interaction could also be disrupted by AKAP-IS, a consensus RII-anchoring disruptor peptide (Alto et al., 2003). However, the p110γ sequence defined by the peptide array is not predicted to form a helical domain, and the interaction with RIIα appears to rely on two positively charged residues. Nonetheless, these findings are in line with the notion that the family of AKAPs, which currently includes 45 genes and their splice variants, exhibits substantial heterogeneity in sequence, yet always featuring the ability to tether PKA at subcellular locations.

The PKA associated with p110γ not only influences the catalytic activity of PDE3B, but also modulates the lipid kinase activity of p110γ itself. Indeed, the proximity of PKA and p110γ within the same macromolecular complex allows active PKA to phosphorylate both PDE3B and p110γ. The phosphorylation of p110γ by PKA on T1024 results in a negative modulation of p110γ kinase activity. T1024 resides in an α helix situated in close proximity to the ATP-binding pocket, and therefore the functional effects of this phosphorylation on the kinase activity of p110γ may derive from a conformational change disturbing the catalytic pocket. This mechanism is supported by our findings with the phosphomimetic T1024D mutant, which resulted in decreased lipid kinase activity. T1024 of p110γ is highly conserved among species and is not represented in the other class I PI3K isoforms, which are, however, inhibited by their autophosphorylation within the catalytic domain (Czupalla et al., 2003).

Modulation of p110γ by PKA has relevant functional implications in vivo in the myocardium. While the β-AR/cAMP pathway that activates PKA also triggers the PI3K pathway (Jo et al., 2002; Leblais et al., 2004), our results indicate that in physiological conditions, p110γ activity is negligible, owing to its low expression levels and to the inhibitory phosphorylation by PKA. Instead, other G protein-coupled p110 isoforms, such as p110β (Ciraolo et al., 2008; Guillermet-Guibert et al., 2008; Jia et al., 2008), appear to be the main PI3K catalytic subunits responsible for the production of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and the consequent activation of Akt upon β-AR stimulation. Our findings are in line with the view that, in physiological conditions, p110γ activity undergoes a delicate negative regulation in response to cAMP production and PKA activation. This inhibitory effect can be linked to the well-established view that, while class IA exerts beneficial effects on the myocardium (Oudit and Penninger, 2009), p110γ function is associated with detrimental responses to cardiac stress (Crackower et al., 2002; Rockman et al., 2002). In heart failure, p110γ is upregulated, and due to defective PKA-mediated inhibition, its activity is significantly enhanced. Of note, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 measurement in TAC-treated hearts showed that only in p110γKD/KD and not in p110βKD/KD hearts (data not shown) is PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 lower than in wild-type controls, thus confirming a prominent role of the p110γ isoform in heart failure (Figure 7D).

The negative influence exerted by p110γ catalytic activity on the development of heart failure appears to be related to its impact on β-AR pathway, a key regulator of heart contractility (Rockman et al., 2002). Indeed, p110γ promotes the desensitization and downregulation of β-ARs through its interaction with β-ARK1 (Naga Prasad et al., 2001) and through the recruitment of PH domain-containing proteins such as AP-2 (Naga Prasad et al., 2002), required for the assembly of β-AR downregulation machinery. Consistent with these observations, genetic ablation of p110γ, expression of a catalytically inactive p110γ, or administration of a selective p110γ inhibitor to wild-type mice slightly but significantly increased cardiac β-AR density. A trend toward elevated β-AR surface expression has been already reported in a previous study conducted on p110γ-deficient mice (Nienaber et al., 2003). In our hands, while basal myocardial β-AR expression was only marginally affected by the inactivation of p110γ, the effect of p110γ on β-AR downregulation appeared prominent during adrenergic stress and pressure overload-induced heart failure. Consistently, in failing hearts, p110γ catalytic activity appeared significantly enhanced and occurred in a context where expression of p110γ and its adaptor p101 was dramatically upregulated. This effect limited the organization of complexes with p84/87 and PKA, thus reducing PKA-mediated inactivation of p110γ. In agreement, blockade of p110γ activity either genetically or pharmacologically led to a renormalization of β-AR density in heart failure, improving compromised cardiac contractility.

In summary, our results establish that myocardial p110γ connects the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and cAMP signaling pathways. We show that anchored PKA is the key regulator of enzymes in this macromolecular complex and that PKA locally controls PDE3B activity, reducing cAMP levels. This finding provides an explanation for the longstanding conundrum of how the p110γ kinase-independent function can promote cAMP degradation (Patrucco et al., 2004). On the other hand, PKA inhibits p110γ activity to maintain myocardial β-ARs on the cell surface. In heart failure, uncoupling of p110γ from its negative regulator PKA results in β-AR downregulation. Pharmacological inhibition of p110γ restores the physiological condition, with beneficial effects on β-AR density and, ultimately, on cardiac contractility, thus establishing p110γ targeting as a potential treatment for heart failure.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

p110γ knockout (Hirsch et al., 2000), p110γ kinase-dead (Patrucco et al., 2004), and p110β kinase-dead mice (Ciraolo et al., 2008) are all in a C57BL/6J background. C57BL/6J wild-type mice were used as controls.

Hearts and Cell Lysis, Protein Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blotting

Hearts, adult rat cardiomyocytes, and HEK293T cells were homogenized in 1% Triton X-100 buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were analyzed for immunoblotting or for immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies.

Lipid Kinase Assay

Immunoprecipitated p110γ was incubated in lipid kinase buffer containing phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, ATP, and 5 μCi of 32P-ATP for 10 min at 30°C at 1200 rpm. The reaction was stopped by addition of HCl, and lipids were extracted using chloroform/methanol. The organic phase was spotted on thin-layer chromatography plates and resolved with chloroform/methanol/ammonium hydroxide/water. Dried plates were exposed for autoradiography.

Transverse Aortic Constriction and AS605240 Treatment

In vivo pressure overload was imposed on the left ventricle by surgical banding of the transverse aorta, as previously described (Patrucco et al., 2004). Sham-operated animals underwent the same surgical procedure without TAC. 2D guided M-mode echocardiography was performed in anesthetized mice to assess cardiac function. Fractional shortening (FS) lower than 30% was used as a threshold to discriminate between compensated and decompensated hearts. Mice displaying a 25%–30% FS were injected i.p. daily for 1 week with either 10 mg/kg AS605240 or vehicle.

β-AR Density Measurement

Mouse hearts were homogenized in 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 μM leupeptin, 100 μM benzamidine, and 100 μM PMSF and centrifuged at 800 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were filtered and centrifuged at 25,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The pelleted membranes were washed in acidified ice-cold binding buffer before being resuspended in binding buffer. Total β-AR density was determined by incubation of membrane proteins with a saturating concentration of 125I-labeled cyanopindolol. Nonspecific binding was determined as previously described (Ciccarelli et al., 2008). Reactions were conducted at 37°C for 1 hr and terminated by vacuum filtration. After ice-cold washing, bound radioactivity was assessed on a gamma counter. All assays were performed in triplicate, and receptor density (femto-moles) was normalized to milligrams of membrane protein.

Data and Statistical Analyses

Prism software (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. P values were calculated by using Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA test, followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis when appropriate. p < 0.05 was considered significant (*), p < 0.01 was considered very significant (**), and p < 0.001 was considered extremely significant (***). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details and for remaining procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M. Zaccolo (University of Glasgow), J. Beavo (University of Washington), J. Hamm (University of Torino), and all the members of E.H.’s lab. This work was supported by grants from Fondation Leducq (06CDV02 to E.H., J.D.S., G.S.B., and M.D.H.), the European Union Sixth Framework Program EuGeneHeart (E.H.), Telethon (E.H.), Regione Piemonte (E.H.), University of Torino (E.H.), AIRC (E.H.), NIH (grant HL08836 to J.D.S.), and Medical Research Council UK (G0600675 to G.S.B. and M.D.H.).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, Supplemental References, seven figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online at doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.030.

References

- Alto NM, Soderling SH, Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Fayos R, Jennings PA, Scott JD. Bioinformatic design of A-kinase anchoring protein-in silico: a potent and selective peptide antagonist of type II protein kinase A anchoring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4445–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330734100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, Cubicciotti RS, Sageman WS, Lurie K, Billingham ME, Harrison DC, Stinson EB. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR, Hershberger RE, Port JD, Gilbert EM, Sandoval A, Rasmussen R, Cates AE, Feldman AM. Beta-adrenergic pathways in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 1990;82 (2 Suppl):I12–I25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DW, Stofko-Hahn RE, Fraser ID, Bishop SM, Acott TS, Brennan RG, Scott JD. Interaction of the regulatory subunit (RII) of cAMP-dependent protein kinase with RII-anchoring proteins occurs through an amphipathic helix binding motif. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14188–14192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli M, Santulli G, Campanile A, Galasso G, Cervèro P, Altobelli GG, Cimini V, Pastore L, Piscione F, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. Endothelial alpha1-adrenoceptors regulate neo-angiogenesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:936–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciraolo E, Iezzi M, Marone R, Marengo S, Curcio C, Costa C, Azzolino O, Gonella C, Rubinetto C, Wu H, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110beta activity: key role in metabolism and mammary gland cancer but not development. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti M, Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crackower MA, Oudit GY, Kozieradzki I, Sarao R, Sun H, Sasaki T, Hirsch E, Suzuki A, Shioi T, Irie-Sasaki J, et al. Regulation of myocardial contractility and cell size by distinct PI3K-PTEN signaling pathways. Cell. 2002;110:737–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czupalla C, Culo M, Müller EC, Brock C, Reusch HP, Spicher K, Krause E, Nürnberg B. Identification and characterization of the autophosphorylation sites of phosphoinositide 3-kinase isoforms beta and gamma. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11536–11545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degerman E, Landström TR, Wijkander J, Holst LS, Ahmad F, Belfrage P, Manganiello V. Phosphorylation and activation of hormone-sensitive adipocyte phosphodiesterase type 3B. Methods. 1998;14:43–53. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denniss AR, Marsh JD, Quigg RJ, Gordon JB, Colucci WS. Beta-adrenergic receptor number and adenylate cyclase function in denervated transplanted and cardiomyopathic human hearts. Circulation. 1989;79:1028–1034. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.5.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KL, Khouangsathiene S, Kapiloff MS, Mouton R, Hill EV, Houslay MD, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. mAKAP assembles a protein kinase A/PDE4 phosphodiesterase cAMP signaling module. EMBO J. 2001;20:1921–1930. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt S, Böhm M, Erdmann E, Lohse MJ. Analysis of beta-adrenergic receptor mRNA levels in human ventricular biopsy specimens by quantitative polymerase chain reactions: progressive reduction of beta 1-adrenergic receptor mRNA in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:146–154. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MG, Lygren B, Dokurno P, Hoshi N, McConnachie G, Taskén K, Carlson CR, Scott JD, Barford D. Molecular basis of AKAP specificity for PKA regulatory subunits. Mol Cell. 2006;24:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillermet-Guibert J, Bjorklof K, Salpekar A, Gonella C, Ramadani F, Bilancio A, Meek S, Smith AJ, Okkenhaug K, Vanhaesebroeck B. The p110beta isoform of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signals downstream of G protein-coupled receptors and is functionally redundant with p110gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707761105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausken ZE, Coghlan VM, Hastings CA, Reimann EM, Scott JD. Type II regulatory subunit (RII) of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase interaction with A-kinase anchor proteins requires isoleucines 3 and 5. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24245–24251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in inflammation. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Braccini L, Ciraolo E, Morello F, Perino A. Twice upon a time: PI3K’s secret double life exposed. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Liu Z, Zhang S, Liu P, Zhang L, Lee SH, Zhang J, Signoretti S, Loda M, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Essential roles of PI(3)K-p110beta in cell growth, metabolism and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;454:776–779. doi: 10.1038/nature07091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo SH, Leblais V, Wang PH, Crow MT, Xiao RP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase functionally compartmentalizes the concurrent G(s) signaling during beta2-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Res. 2002;91:46–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024115.67561.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfant BG, Zhao D, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Wilson LS, Cai S, Chen SR, Maurice DH, Backx PH. PI3Kgamma is required for PDE4, not PDE3, activity in subcellular microdomains containing the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium ATPase in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2007;101:400–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblais V, Jo SH, Chakir K, Maltsev V, Zheng M, Crow MT, Wang W, Lakatta EG, Xiao RP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase offsets cAMP-mediated positive inotropic effect via inhibiting Ca2+ influx in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2004;95:1183–1190. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150049.74539.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naga Prasad SV, Barak LS, Rapacciuolo A, Caron MG, Rockman HA. Agonist-dependent recruitment of phosphoinositide 3-kinase to the membrane by beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1. A role in receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18953–18959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naga Prasad SV, Laporte SA, Chamberlain D, Caron MG, Barak L, Rockman HA. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates beta2-adrenergic receptor endocytosis by AP-2 recruitment to the receptor/beta-arrestin complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:563–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienaber JJ, Tachibana H, Naga Prasad SV, Esposito G, Wu D, Mao L, Rockman HA. Inhibition of receptor-localized PI3K preserves cardiac beta-adrenergic receptor function and ameliorates pressure overload heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1067–1079. doi: 10.1172/JCI18213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudit GY, Penninger JM. Cardiac regulation by phosphoinositide 3-kinases and PTEN. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:250–260. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrucco E, Notte A, Barberis L, Selvetella G, Maffei A, Brancaccio M, Marengo S, Russo G, Azzolino O, Rybalkin SD, et al. PI3Kgamma modulates the cardiac response to chronic pressure overload by distinct kinase-dependent and -independent effects. Cell. 2004;118:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino C, Schroder JN, Lima B, Villamizar N, Nienaber JJ, Milano CA, Naga Prasad SV. Dynamic regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-gamma activity and beta-adrenergic receptor trafficking in end-stage human heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:2571–2579. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature. 2002;415:206–212. doi: 10.1038/415206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JD, Pawson T. Cell signaling in space and time: where proteins come together and when they’re apart. Science. 2009;326:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1175668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskén KA, Collas P, Kemmner WA, Witczak O, Conti M, Taskén K. Phosphodiesterase 4D and protein kinase a type II constitute a signaling unit in the centrosomal area. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21999–22002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt P, Dorner MB, Schaefer M. Characterization of p87PIKAP, a novel regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma that is highly expressed in heart and interacts with PDE3B. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9977–9986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby D, Wong W, Schaack J, Scott JD, Cooper DM. An anchored PKA and PDE4 complex regulates subplasmalemmal cAMP dynamics. EMBO J. 2006;25:2051–2061. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Kobilka BK. Myocyte adrenoceptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1530–1532. doi: 10.1126/science.1079206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.