Abstract

Objectives

To investigate factors which influenced UK-trained doctors to emigrate to New Zealand and factors which might encourage them to return.

Design

Cross-sectional postal and Internet questionnaire survey.

Setting

Participants in New Zealand; investigators in UK.

Participants

UK-trained doctors from 10 graduation-year cohorts who were registered with the New Zealand Medical Council in 2009.

Main outcome measures

Reasons for emigration; job satisfaction; satisfaction with leisure time; intentions to stay in New Zealand; changes to the UK NHS which might increase the likelihood of return.

Results

Of 38,821 UK-trained doctors in the cohorts, 535 (1.4%) were registered to practise in New Zealand. We traced 419, of whom 282 (67%) replied to our questionnaire. Only 30% had originally intended to emigrate permanently, but 89% now intended to stay. Sixty-nine percent had moved to take up a medical job. Seventy percent gave additional reasons for relocating to New Zealand including better lifestyle, to be with family, travel/working holiday, or disillusionment with the NHS. Respondents' mean job satisfaction score was 8.1 (95% CI 7.9–8.2) on a scale from 1 (lowest satisfaction) to 10 (highest), compared with 7.1 (7.1–7.2) for contemporaries in the UK NHS. Scored similarly, mean satisfaction with the time available for leisure was 7.8 (7.6–8.0) for the doctors in New Zealand, compared with 5.7 (5.6–5.7) for the NHS doctors. Although few respondents wanted to return to the UK, some stated that the likelihood of doctors' returning would be increased by changes to NHS working conditions and by administrative changes to ease the process.

Conclusions

Emigrant doctors in New Zealand had higher job satisfaction than their UK-based contemporaries, and few wanted to return. The predominant reason for staying in New Zealand was a preference for the lifestyle there.

Introduction

International medical migration is a longstanding phenomenon. In the first half of the 20th century, the movement of doctors was generally from wealthy to poor countries. In the second half, the flow became pronounced from what are now known as developing (or low and middle income) countries to developed countries. Countries like the United States (US), Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom (UK) became dependent on inward migration of international medical graduates (IMGs), most notably from the developing world. While the migration of doctors from low and middle income countries is a major concern, there is also substantial movement of doctors between developed countries. This is an important issue for the UK, which, when considering flows between developed countries, has been a net exporter of doctors. In a study of migration between the UK, US, Canada and Australia, Mullan et al. recently reported that there has been substantial migration of UK-trained doctors to the Australia, Canada and the US, unmatched by migration to the UK on a similar scale from these three countries.1 Workforce retention, even between developed countries, is important for global health equity:2 if a developed country has a net loss of doctors to other developed nations, there is a greater likelihood that it will make up shortfalls by recruitment from the developing world.

There is surprisingly little systematic information about doctors who leave the UK. Health workers' migration has been categorized as being influenced by dissatisfaction with working or living conditions in their home country (‘push’ factors) and by the attractions of working and living in the destination country (‘pull’ factors).3 The extent to which each applies to UK-trained doctors who migrate to other developed countries is unknown. We explored the characteristics of UK-trained doctors who have moved to New Zealand (NZ), factors that influenced them to go, and whether they intend to stay. We were interested, in particular, in whether differences between the UK and NZ healthcare systems, or differences between lifestyles and society between the UK and NZ, were major motivating factors. We chose NZ partly because it is a popular destination for UK doctors who emigrate; and partly because it has a single, national, publicly available source of names and addresses of registered medical practitioners.

Methods

Since the mid-1970s, the UK Medical Careers Research Group (MCRG) has undertaken longitudinal national cohort studies of all UK medical qualifiers of 1974, 1977, 1983, 1988, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2000, 2002 and 2005. The methods used are described elsewhere.4,5 In 2009, the addresses in NZ of UK-trained medical graduates in these cohorts, who had previously been surveyed by us and were registered with the Medical Council of New Zealand, were obtained from the Council's public register. A questionnaire was sent by hard-copy post and email to the doctors, with two reminders to those who did not initially respond, between December 2009 and March 2010.

Structured questions were asked about reasons for leaving the UK, going to NZ, and about possibly returning to the UK. In addition, respondents were invited to comment to expand on their reasons for leaving the UK, moving to NZ, and about factors that might influence decisions to return. These comments were categorized and analysed thematically. SPSS version 17 was used for data analysis.

Results

Target population and response rates

The New Zealand Medical Council found and provided current registered addresses for 535 UK-trained doctors from the 10 cohorts. This represented 1.4% of all 38,821 UK-trained graduates in the cohorts studied, a percentage which did not differ appreciably by year of graduation (Table 1).

Table 1.

UK medical graduates of 1974–2005; and numbers and percentages registered to practise medicine in New Zealand in 2009

| Graduation year | Cohort size | Registered in New Zealand (n) | In New Zealand (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974–1988 | 13066 | 190 | 1.5 |

| 1993–1999 | 11758 | 151 | 1.3 |

| 2000–2005 | 13997 | 194 | 1.4 |

| Total | 38821 | 535 | 1.4 |

Includes the graduates of 1974, 1977, 1983, 1988, 1993, 1996, 1999, 2000, 2002, and 2005

Test of homogeneity of percentage in New Zealand: χ22 = 1.3, P = 0.52

Following mailing, 113 questionnaires were returned to us indicating that the doctor was no longer at the address, and three doctors wrote declining to participate. Of the former, 74% (84/113) were recent graduates who graduated between 2000 and 2005. Many of these may have been short-stay doctors or those moving within NZ between junior posts, whose addresses had changed. The response rate from the remainder was 67.3% (282/419), with 206 replying by post and 76 online. The response rate was 83% (152/183) from those who graduated in 1974–1988; 62% (79/127) from those who graduated in 1993–1999; and 47% (51/109) from those who graduated in 2000–2005.

Demographics of responders

Of 282 responders, 53% were men and 47% women. Thirty-two percent were below the age of 40 years, 29% were aged 40–49 years, and 38% were aged 50 years and over (two did not provide their age). Only 2% (5 doctors) had been overseas students, i.e. their homes had been outside the UK when they commenced medical study in the UK; and 8% (22) were graduate students when they entered medical school.

Six responders were not working in medicine and a further two did not give employment details; 109 (39%) were working in general practice, 28 (10%) in anaesthetics, 27 (10%) in hospital medical specialties, 22 (8%) in psychiatry, 21 (8%) in the surgical specialties, 17 (6%) in accident and emergency medicine, 12 (4%) in paediatrics, and 38 (13%) in other specialties. Of the 274 responders who gave details of medical posts, 166 (60%) were in the public sector, 73 (26%) were in the private sector, and 35 (14%) described their work as mixed public and private sector.

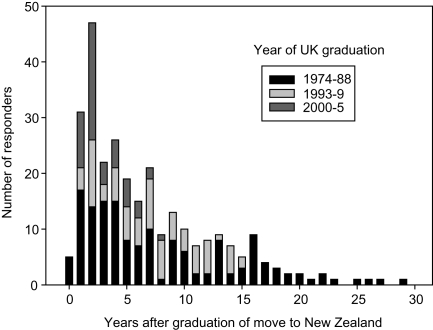

Moving to New Zealand

There were 79 responders (28%) who migrated from the UK before the year 1990; 67 (24%) who moved between 1990 and 1999; 63 (22%) who moved between 2000 and 2004; 72 (26%) who moved since 2005; and one responder did not specify the year of move. Figure 1 illustrates the time after graduation at which doctors from different qualifying years moved to NZ; 37% had moved within 3 years of qualification, 21% between 4 and 6 years, 15% between 7 and 9 years, and 26% at 10 years or more. Of those who migrated in or after 2000, only 38% (51/135) were from the cohorts who qualified in 2000 or after.

Figure 1.

Year of graduation and year of move to New Zealand

Original intentions about staying in New Zealand

We asked doctors how long they had intended to stay in NZ at the time they left the UK. Only 30% had decided to move to NZ permanently, 48% intended to stay for a limited time and return to the UK, and 22% had intended to experience NZ and decide later. There was a rising trend by year of move in the percentage who had intended to move permanently: only 21% (16/78) of those who moved before 1990 had intended to move permanently, as had 28% (19/67) of those who moved between 1990 and 1999, 34% (21/62) of those who moved between 2000 and 2004, and 39% (28/72) of those who moved after 2004 (χ2 test for linear trend = 6.5, 1 df, P = 0.01). Of those who specified that they would stay for a limited time, 68% specified 6 months to one year.

Reasons for going to New Zealand

Participants were asked ‘At the time of first going to New Zealand, what were your reasons for going?’ They were offered five pre-specified reasons and invited to tick more than one if more than one applied. These were: (1) professional, for a medical job; (2) professional, for other work; (3) personal, for a holiday; (4) personal, to be with family or friends; and (5) other reasons.

Those who specified ‘other reasons’ were asked to expand using their own words, and we coded their answers by theme. Some who chose one of the first four options also gave further reasons in their own words. All are included in the totals in Table 2.

Table 2.

Responses to the question ‘At the time of first going to New Zealand, what were your reasons for going?’: numbers and percentages of respondents

| Reasons for moving to NZ | % | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-specified options* | ||

| For a medical job | 69 | 192 |

| For other work | 2 | 6 |

| Personal (holiday) | 10 | 29 |

| Personal (family/friends) | 15 | 41 |

| Other reasons | 40 | 112 |

| Additional free text reasons, classified as:† | 70 | 192 |

| Personal: travel/holiday/to be with family or friends | 30 | 84 |

| Better lifestyle in NZ | 23 | 66 |

| Disillusioned with the NHS | 16 | 44 |

| Change of environment | 9 | 24 |

| Lack of jobs in the NHS | 7 | 20 |

| Better opportunity in NZ | 7 | 18 |

| Previous NZ experience/recommendation | 6 | 16 |

| Disillusioned with life in UK | 3 | 9 |

*Responses to the five pre-specified categories. Doctors were invited to select more than one reason if more than one applied

†Reasons are based on thematic coding by the authors of free-text reasons given by the respondents

Sixty-nine percent of the doctors moved to take up a medical job and 2% for other work; 25% moved for personal reasons. In addition, 40% specified ‘other reasons’ (Table 2) and, in all, 70% gave reasons in their own words. The most frequent related to travel, holiday or being with family or friends (30% of all respondents); wanting a better lifestyle in NZ (23%); or disillusionment with the NHS (16%).

Differences in the reasons given by year of move and graduation year were generally modest, with the following exceptions. Disillusionment with the NHS was cited by 29% (21/72) of the graduates who moved to NZ after 2004 compared with 11% (23/209) of those who moved earlier (χ21 =12.0, P = 0.001). Disillusionment with the NHS was cited by 31% (16/51) of the graduates of 2000–2005 compared with 15% (12/80) of the graduates of the 1990s and 11% (16/151) of earlier graduates (χ22 =12.5, P = 0.002). Seeking a better lifestyle was cited by 33% (44/135) of those who moved to NZ after 1999 compared with 15% (22/146) of those who moved earlier (χ21 =11.0, P = 0.001).

Illustrative quotes under each theme are shown in Box 1. Some who gave being with family/spouse as a reason for leaving the UK were partners of New Zealanders who wanted to return and others were moving with their spouse (typically, another doctor) for professional reasons. Many who expressed disillusionment with the NHS, particularly those who had recently qualified, mentioned training issues and the Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) initiative was singled out for comment.

Box 1. Illustrative quotes for reasons for leaving the UK.

| Lifestyle (cited by 66 doctors, or 23% of all responders) | ‘Better lifestyle – outdoor sports and activities… better weather. More relaxed. Less uptight. Good place to bring up children (no children at time of move), Kiwi values are similar to my own.’ 2000 graduate, moved in 2003 |

| ‘Lifestyle. Leisure. Outdoor pursuits.’ 1999 graduate, moved in 2001 | |

| ‘Better lifestyle. Better weather. Less crowded.’ 2002 graduate, moved in 2006 | |

| ‘For a better life style and future for my family.’ 1977 graduate, moved in 1996 | |

| Travel/holiday/to be with family or friends (84 doctors, 30% of responders) | ‘Desire to travel, but continue medical training.’ 1977 graduate, moved in 1978 |

| ‘… to travel through India and SE Asia (1 year) and then earn enough money to come home.’ 1974 graduate, moved in 1976 | |

| ‘Wanted to go abroad for a while before embarking on exams, etc. for orthopaedic training. NZ seemed like a great place to go.’ 1977 graduate, moved in 1980 | |

| ‘My husband has dual UK/NZ nationality, and he wanted to move back to NZ.’ 1993 graduate, moved in 2005 | |

| ‘Husband from NZ. Moved so he could complete paediatric training.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 2003 | |

| ‘Husband unable to get consultant post in the UK so moved to NZ.’ 1983 graduate, moved in 1987 | |

| Better opportunities in NZ (18, 7%) | ‘To start training scheme in anaesthesia.’ 1988 graduate, moved in 1991 |

| ‘Excellent funding opportunities to set up a research department.’ 1983 graduate, moved in 1999 | |

| ‘To go there to work for a year in Obs and Gynae but wanted a change and a new challenge.’ 2002 graduate, moved in 2005 | |

| ‘Wanted training in Intensive Care Medicine and there was no proper training route in UK.’ 1993 graduate, moved in 2000 | |

| Lack of jobs in NHS (20, 7%) | ‘I wished to have a permanent job; I was tired of only having locum work. There were no advertised jobs in [named small specialty].’ 1993 graduate, moved in 2007 |

| ‘Training not available in [named small specialty, different from previous quote] in UK in 1994.’ 1983 graduate, moved in 1994 | |

| ‘Husband is an anaesthetist and there were no consultant positions in the UK.’ 2002 graduate, moved in 2008 | |

| ‘… to get away from the lottery and uncertainty of finding jobs in the NHS.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| Disillusioned with the NHS (44, 16%) | ‘Being betrayed by the training system and the implementation of MMC… the lost generation.’ 2000 graduate, moved in 2008 |

| ‘Disenchantment with consultant posts in the NHS. I was single-handed in three posts until the end.’ 1974 graduate, moved in 1999 | |

| ‘Frustration with job selection system.’ 1974 graduate, moved in 1976 | |

| ‘To escape the NHS and MMC.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘Chaos of MTAS. Inability for me and my wife to find work in same part of country.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘Left due to the breakdown of medical training in the UK.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘Disillusioned with NHS. Not sure what career pathway to enter – NHS pushing to make specialty choice after 2 years.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘Frustration at the application process and blind governmental restructuring of the training scheme.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| Change of environment (24, 9%) | ‘To get away from the UK for a while before starting SpR rotation.’ 1993 graduate, moved in 1997 |

| ‘Overseas experience in intensive care medicine.’ 1988 graduate, moved in 1994 | |

| ‘Wanting a working holiday – felt burnt out and I never worked overseas before, felt the change would do me good.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 2006 | |

| ‘To have an experience of a different health system.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 2008 |

Satisfaction with work and leisure

The doctors were asked how much they enjoyed their current position in NZ and how satisfied they were with the amount of time their work left them for family, social and recreational activities. The mean score for enjoyment of work in their current position was 8.1 on a scale from 1 (not enjoying it at all) to 10 (enjoying it greatly). The mean score for satisfaction with time left for recreational activity was 7.8 on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 10 (extremely satisfied). The results were compared with data from our surveys of UK-trained doctors in the NHS in the same graduation year cohorts (Table 3). Both job satisfaction and leisure time satisfaction scores were scored significantly more highly by NZ than by NHS doctors, with leisure time satisfaction scores markedly higher for NZ than for NHS doctors.

Table 3.

Job satisfaction* and satisfaction with leisure time†, comparing UK graduates who have emigrated to New Zealand doctors with their contemporaries in the UK NHS

| Graduation year | Doctors in the UK NHS | Doctors in New Zealand | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | |

| Job satisfaction | ||||

| 1974–1988‡ | 6.9 (6.8, 7.0) | 3876 | 8.2 (8.0, 8.4) | 150 |

| 1993–1999§ | 7.1 (7.0, 7.1) | 1784 | 7.8 (7.5, 8.2) | 79 |

| 2000–2005 | 7.4 (7.4, 7.5) | 3905 | 8.1 (7.7, 8.5) | 49 |

| Total | 7.1 (7.1, 7.2) | 9475 | 8.1 (7.9, 8.2) | 278 |

| Leisure time | ||||

| 1974–1988 | 5.1 (5.0, 5.1) | 7866 | 7.6 (7.3, 7.9) | 150 |

| 1993–1999 | 6.0 (6.0, 6.1) | 5629 | 7.9 (7.5, 8.3) | 79 |

| 2000–2005 | 6.1 (6.0, 6.1) | 5341 | 8.4 (8.0, 8.8) | 50 |

| Total | 5.7 (5.6, 5.7) | 18,836 | 7.8 (7.6, 8.0) | 279 |

*Question asked: ‘How much are you enjoying your current position, on a scale from 1 (not enjoying it at all) to 10 (enjoying it greatly)?’

†Question asked: ‘How satisfied are you with the amount of time your work currently leaves you for family, social and recreational activities, on a scale from 1 (not enjoying it at all) to 10 (enjoying it greatly)?’

‡Question asked of 1974 and 1983 cohorts only (in 1998)

§Question asked of 1999 cohort only (in 2007)

Future career intentions

We asked ‘Apart from temporary visits away from NZ, do you intend to practise medicine in NZ for the foreseeable future?’ with five closed answers: yes, definitely; yes, probably; undecided; no, probably not; no, definitely not. We did not assume that the doctors' only options were to work either in NZ or the UK, so we also asked: ‘How likely are you to return to practise in the UK in the foreseeable future?’ with five answers: very likely; likely; undecided; unlikely; and very unlikely.

Overall, 89% (249/280) definitely or probably intended to continue to practise in NZ, and 81% (228/280) were unlikely or very unlikely to return to the UK. Only 5% would definitely or probably not continue working in NZ, and only 9% were likely or very likely to return to the UK. More recent movers to NZ, and more recent graduates, were slightly less likely to intend to stay in NZ and slightly more likely to intend to return to the UK.

Factors which might increase the likelihood of return to the UK NHS

We asked respondents what incentives or changes to the NHS would increase the likelihood of their return. Although most did not intend to return, 69% (194 responders) offered comments. We coded their responses under nine themes, which we categorized and list here in order of frequency: ‘better working conditions’ (74 doctors); ‘changes to the NHS – including changes to training, management, government policy’ (66); ‘nothing would make me return’ (43); ‘administrative changes to make it easier to return and/or greater recognition of Australasian qualifications’ (33); ‘better work/financial incentives’ (33); ‘change in personal circumstances or family needs’ (17); ‘improved job security’ (13); ‘lifestyle changes’ (12); and ‘change of government or changes in social attitudes in the UK’ (9).

Illustrative quotes are given in Box 2. Comments about work–life balance were categorized under ‘better working conditions’. ‘Changes to the NHS’ was a broad category which encompassed changes to management, government policy and training. The category of ‘administrative changes’ that would make return easier included comments about re-registration with the UK General Medical Council, re-training and recognition of Australasian qualifications and experience.

Box 2. Illustrative quotes for incentives and changes to the NHS that would increase the likelihood of return to the UK.

| Better working conditions (cited by 74 doctors, or 26% of all responders) | ‘Better work–life balance. The low morale and apparent dissatisfaction among the consultant staff that was a big motivator to leave. I'm not sure that has changed.’ 2002 graduate, moved in 2005 |

| ‘Better working conditions with longer appointments and protected administration time as we have in NZ.’ 1983 graduate, moved in 2006 | |

| ‘More flexible hours. Less demand on GPs to provide early morning/evening surgeries.’ 1999 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘A permanent post, more relaxed working environment. Very unlikely to return.’ 1993 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| Changes to the NHS (66 doctors, 23% of responders) | ‘Less Government targets and interference. Better management. Better job satisfaction.’ 1988 graduate, moved in 2004 |

| ‘Less “red tape” and bureaucracy. Less of a political “football”. 1993 graduate, moved in 1994 | |

| ‘Less rigidity in terms of training. More support from employers, managers, peers. More opportunities for study/broadening experiences. Any incentives really – I found there were none while working for the NHS.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| ‘A sensible application process based on clinical experience and curriculum vitae rather than “75 words or less” empathy questions. A medical-based hierarchy rather than a managerial one… recognition for the countless hours of overtime that are aggressively ignored by the management/government.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 | |

| Administrative changes to make it easier to return/recognition of NZ qualifications (33, 12%) | ‘I am currently going through the PMETB bureaucratic process to get on the specialist register in the UK (in case I need to work). It is stressful and a nightmare. I have trained and worked in the UK for many years and have an immaculate training record in NZ. I can't see how this awful process can add any value to the NHS or incentive to return to the UK.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 2002 |

| ‘Easier acceptance of NZ qualifications/experience years for registration with UK GP councils.’ 2000 graduate, moved in 2001 | |

| ‘Hassle-free acceptance of my specialty training and GMC registration.’ 1993 graduate, moved in 1995 | |

| ‘Acceptance of experience/accreditation/seniority/training obtained from 22 years Consultant [named specialty] practice in NZ (… NOT about to re-sit exams, etc.).’ 1974 graduate, moved in 1988 | |

| ‘Would be difficult at present as I am currently in a training scheme here and would have to take a step backwards and would be difficult to get into training in the UK.’ 2000 graduate, moved in 2002 | |

| ‘NZ husband able to work more easily without EU regulations.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 1998 | |

| Better work incentives and/or financial remuneration (33, 12%) | ‘Better pay. Job-sharing opportunities for women including surgical specialties.’ 2005 graduate, moved in 2007 |

| ‘Increased funding for staff and research facilities.’ 1983 graduate, moved in 1999 | |

| ‘An interesting job near my family. One that offers a balance of clinical, research and service development in the role. My perception is that this is unlikely given the direction the NHS has been taking and that it will have only been made worse by the financial crisis.’ 1996 graduate, moved in 2008 |

Analysis by year of qualification showed that, for the most recent cohorts of 2000, 2002 and 2005, 30% of respondents commented on the importance of reducing barriers to re-entry and of the UK accepting Australasian qualifications. This compares with an overall figure of 12%, and it highlights the importance of perceived barriers to re-entry to doctors at relatively early stages in their careers when they may still be considering returning to the UK.

Discussion

Principal findings

Only one-third of the UK-trained doctors in NZ intended definitely to stay there when they first left the UK. By the time of the survey, nine out of 10 intended, definitely or probably, to stay in NZ for the foreseeable future. The majority moved to NZ for professional reasons related to training or longer-term career opportunities. Many were attracted by the lifestyle that they had found in NZ. Smaller numbers moved to be with spouses, family or friends, or to travel. Some had been unable to obtain posts in the NHS and were critical of the NHS and the UK. UK doctors who moved after 2005, as well as more recent graduates, were most likely to cite disillusionment with the NHS, though this was a minority view. Job satisfaction scores and leisure time satisfaction scores were significantly higher among the NZ doctors than their UK medical counterparts. This was so even among doctors who had only been in NZ for a short time. Although most intended to stay in NZ, many offered suggestions about what might make it more likely for UK-trained, overseas-based doctors to return to the UK. These included comments about easing the system of re-registering with the UK General Medical Council, easing re-training, and recognition of Australasian qualifications and experience.

Strengths and weaknesses

Few studies have investigated the factors which influence the migration of UK-trained doctors to practise medicine in other developed countries. This cross-sectional study of UK-trained doctors in NZ provides a snapshot which may be relevant to the broader community of UK-trained doctors who have emigrated to other high-income countries. We estimate that about 5–8% of the doctors in the MCRG cohorts are in medicine outside the UK; and our data from respondents indicate that the most popular destinations are NZ, Australia, Canada and the US.6

The study has some limitations. First, the response rate for the most recent graduation cohorts was appreciably lower than that for the older cohorts. The response rate was 83% from the doctors who had qualified in 1974–1988 and the profile of these older doctors is the least likely to be influenced by any non-responder bias. We have no way of knowing whether non-respondents in the more recent cohorts received the questionnaire but did not respond, or whether the questionnaire never reached them. Recent graduates will have migrated more recently and may have less stable places of residence and hence be more difficult to contact. Second, our study design was cross-sectional – a survey of doctors of different generations who were in NZ in 2009 – and it did not include doctors who had initially gone to NZ but subsequently returned to the UK. As such, we have no comparative data on ‘returners’ to the UK, who may have had different perceptions about the attractiveness of life and work in NZ. Third, it was beyond our remit to study NZ-qualified doctors who subsequently migrated to practise in the UK NHS. These, too, may have useful insights into the advantages and disadvantages of living and working in NZ and the UK.

Meaning of the study

Workforce retention is a key part of the strategies recommended by the OECD to address shortages in health workers in the face of rising demands for healthcare.6,7 Considering migration between high-income countries, the UK is a net exporter of physicians compared to its English-speaking OECD counterparts.8

The percentage of responders that currently intend to work permanently in NZ is considerably higher than the percentage that originally intended to stay. This, and the emphasis that many respondents placed on desirable ‘lifestyle’ factors in NZ, suggests that ‘pull’ factors outside the control of any NHS changes are important in motivating doctors to migrate and stay in NZ. UK-trained doctors who went to NZ, not necessarily intending to stay, reported a strong liking for the lifestyle that NZ has to offer; and this was one of the main reasons that they chose to stay permanently. When asked about their reasons for going to NZ initially, the majority of doctors specified that it was to take up a medical job, but many also cited other reasons, the commonest of which were based around lifestyle. This was reflected strongly in the comments section of the survey. NZ was seen as a ‘safe place to raise a family’ with a good climate and plentiful attractive outdoor resources.

However, there are also some work-related factors that doctors rate more favourably in NZ than in the NHS. Grant reported that doctors in the UK are less satisfied in their jobs than their counterparts in NZ.9 Our findings showed that the doctors now working in NZ report, on average, higher levels of enjoyment of their jobs, and they also feel more satisfied with the time they have available for social, recreational and family activities, than their NHS counterparts from the same cohorts. Some respondents had left the UK because they were disillusioned with the NHS or because they did not have a job or a place on a training programme. This was significantly more evident for those who had moved after 2004.

Many respondents commented on factors that might influence the return of doctors to the UK. We report what they said, and do not make judgements on whether the doctors were right or wrong. They wrote about better working conditions, less paperwork, and improved training opportunities. Some relayed their frustration at how difficult, in their experience, re-entry to the UK medical workforce seemed to be. Some said that, despite being UK medical graduates, it seemed difficult to re-enter at the level they had attained in NZ, even if only for short-term locum work. Criticism was levelled at European Union regulations and restrictions, the requirement to travel to the UK for interviews, and the UK's apparent unwillingness to recognize specialist training qualifications from Australasian colleges. In summary, although the lure of an overseas lifestyle cannot readily be influenced by NHS policy, ease of re-entry of UK-trained doctors to UK medicine might be a factor worth consideration.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health; the views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department

Ethical approval

National Research Ethics Service, following referral to the Brighton and Mid-Sussex Research Ethics Committee in its role as a multicentre research ethics committee (ref 04/Q1907/48)

Guarantor

TWL

Contributorship

All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; MJG and TWL planned and designed the survey; all authors planned the data analysis; AS undertook the data analysis; TWL provided statistical support; AS wrote the first draft of the paper; all authors contributed to further drafts and approved the final version; AS undertook the work as part of his MSc in Global Health Science at the University of Oxford

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emma Ayres who administered the surveys, Janet Justice and Alison Stockford for their careful data entry, and all the doctors who participated in the surveys

Reviewer

John Collins

References

- 1.Mullan F, Frehywot S, Jolley LJ Aging primary care, and self-sufficiency: health care workforce challenges ahead. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36:703–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development The Looming Crisis in the Health Workforce: How can OECD countries respond? Paris: OECD Publishing, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Health Workforce Alliance – World Health Organization Geneva: WHO, 2009. See http://www.ghwa.org (last checked 1 August 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert T, Goldacre MG, Turner G Career choices of United Kingdom medical graduates of 1999 and 2000: questionnaire surveys. BMJ 2003;326:194–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G Career choices of United Kingdom medical graduates of 2002: questionnaire survey. Med Educ 2006;40:514–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Health Organization International Migration of Health Workers: Improving International Co-operation to Address the Global Health Workforce Crisis. Joint OECD–WHO Policy Brief. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS staff 1999–2009 Overview See http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/workforce/nhs-staff-numbers/nhs-staff-1999-2009-overview (last checked August 2010)

- 8.Mullan F The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1810–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant P Physician job satisfaction in New Zealand versus the United Kingdom. N Z Med J 2004;117:U1123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]