Abstract

Alphaviruses are small, enveloped viruses, ~70 nm in diameter, containing a single-stranded, positive-sense, RNA genome. Viruses belonging to this genus are predominantly arthropod-borne viruses, known to cause disease in humans. Their potential threat to human health was most recently exemplified by the 2005 Chikungunya virus outbreak in La Reunion, highlighting the necessity to understand events in the life-cycle of these medically important human pathogens. The replication and propagation of viruses is dependent on entry into permissive cells. Viral entry is initiated by attachment of virions to cells, leading to internalization, and uncoating to release genetic material for replication and propagation. Studies on alphaviruses have revealed entry via a receptor-mediated, endocytic pathway. In this paper, the different stages of alphavirus entry are examined, with examples from Semliki Forest virus, Sindbis virus, Chikungunya virus, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus described.

1. Alphaviruses

Alphaviruses are primarily arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) within the family Togaviridae. Viruses belonging to this genus are often classified as either New World alphaviruses, or Old World alphaviruses, depending on the geographic location from which they were originally isolated [1]. New World alphaviruses, including Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) and Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV), typically cause encephalitis in humans and other mammals, whereas Old World alphaviruses, such as Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), O'Nyong-Nyong virus (ONNV), Ross River virus (RRV), Semliki Forest virus (SFV), and Sindbis virus (SINV), cause a fever, rash, and arthralgia syndrome that rarely causes fatality [2]. While early studies on alphaviruses focused on the prototypic SFV and SINV due to their ability to grow to high titres in cell culture while being nonpathogenic to humans, recent attention has been directed towards investigating CHIKV. The 2005 outbreak of CHIKV in La Reunion infected 40% of the 785,000 population, resulting in 250 fatal cases [3]. The reemergence of CHIKV reiterates the potential threat that alphaviruses pose to human health, and the necessity to understand mechanisms involved in alphavirus biology.

2. Genomic Composition and Virion Structure

Alphaviruses are small, icosahedral-shaped, enveloped viruses, approximately 70 nm in diameter [4–6]. The alphavirus virion has a host-cell acquired lipid membrane [6–9]. Embedded within this membrane are 80 spikes, arranged in a T = 4 icosahedral [6, 9]. The glycoproteins E1 and E2 associate as heterodimer subunits, which are in turn assembled into trimers to form the spike protrusions [9–11]. Both E1 and E2 are transmembrane proteins with C-terminal cytoplasmic regions that are thought to interact with the nucleocapsid [12, 13].

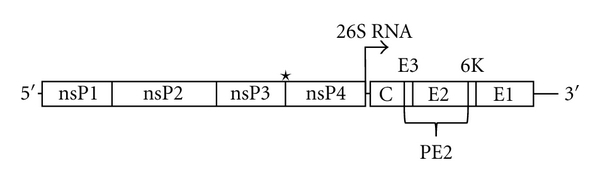

The alphavirus genome is a single-stranded, positive-sense, RNA genome approximately 12 Kb in length [14, 15]. In addition to genomic length RNA, subgenomic RNA encoding the structural proteins is also generated, with both species containing a 5′ cap and a poly(A) tail [14–16]. The coding sequence consists of two large open reading frames (ORFs); the N-terminal ORF encodes the nonstructural polyprotein while the C-terminal ORF encodes the structural polyprotein (Figure 1). The two polyproteins are cleaved posttranslationally by viral (cysteine) and host proteases. The four nonstructural proteins (nsP1 to 4) and their cleavage intermediates are involved in RNA replication, with the five structural proteins (C, E3, E2, 6K, E1) and their cleavage intermediates required for viral encapsidation and budding (Figure 1) [15, 17, 18].

Figure 1.

Alphavirus genome. The alphavirus genome is single-stranded, positive-sense RNA, encoding two open reading frames. The nonstructural proteins are translated from the genomic RNA while the structural proteins are translated from subgenomic 26S RNA (promoter as indicated). The two polyproteins are cleaved by viral cysteine, and host proteases to generate the individual protein products. *denotes leaky stop codon.

The alphavirus nsP1 possesses both guanine-7-methyltransferase and guanylyl transferase activities required for capping and methylation of newly synthesized viral genomic and subgenomic RNAs [19, 20]. During RNA replication, nsP1 is thought to anchor replication complexes to cellular membranes [21]. The alphavirus nsP2 exhibits RNA triphosphatase/nucleoside triphosphatase, as well as helicase activity within the N-terminal half [22–24] while the C-terminal half encodes the viral (papain-like) cysteine protease required for processing of the nonstructural polyprotein [17, 25]. Crystal structures of the CHIKV and VEEV nsP3 N-terminus indicate ADP-ribose 1-phosphate phosphatase and RNA-binding activity [26] while mutagenesis studies also reveal a role for nsP3 in modulating pathogenicity in mice [27, 28]. The nsP4 protein functions as the RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp), containing the catalytic GDD motif in the C-terminus [29]. It has also been hypothesized that nsP4 acts as a scaffold for interaction with other nsPs or host proteins via its N-terminal [30], with adenylyl transferase activity also observed [31].

During nucleocapsid formation, the alphavirus capsid protein (C) binds viral genomic RNA via N-terminal Arg, Lys, and Pro residues [32, 33]. Mutagenesis studies identified a leucine zipper located within this region essential for formation of nucleocapsid-like particles, presumably mediating dimerization during virus assembly [34]. The protein C-terminal is the serine-protease domain [18, 35], which also contains a hydrophobic pocket for glycoprotein binding adjacent to the substrate-binding site [12]. The role of the structural protein E3 is currently undefined, and appears to vary between different alphaviruses. While the E3 protein of SFV is found associated with virions [36], the E3 protein is not incorporated into virions of other alphaviruses including CHIKV, SINV, or WEEV [37]. The E2 glycoprotein of alphaviruses responsible for receptor binding is embedded within the membrane courtesy of 30 C-terminal residues [38–40]. Amino acid changes identified the E2 protein as a determinant of neurovirulence [41–43]. Site-directed mutagenesis identified an Tyr-X-Leu tripeptide within the endodomain required for interaction with the capsid protease domain [12, 13, 44], in concert with conserved Cys residues that are modified by palmitoylation [45]. 6K is a palmitoylated structural protein essential for alphavirus particle assembly [46, 47], where it is thought to influence transport to sites of virion assembly at the plasma membrane, before being incorporated into virions in small amounts [46, 48, 49]. The alphavirus 6K protein has also been classified as a viroporin due to its ability to form cation-selective ion channels and alter membrane permeability in bacterial and mammalian cells [50–52]. The E1 protein is the alphavirus fusion protein [53, 54], with a fusion peptide residing within a highly conserved hydrophobic domain [38].

3. Alphavirus Life-Cycle

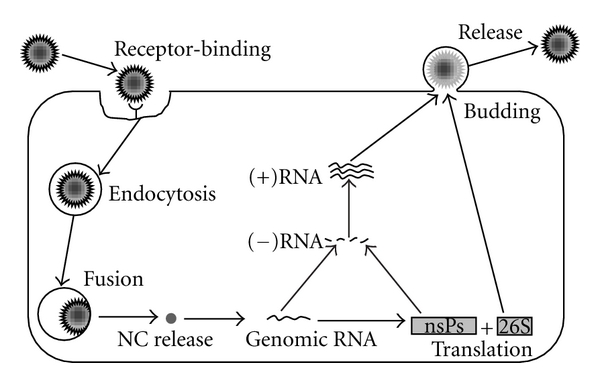

Upon entry, alphavirus particles undergo disassembly, releasing genomic RNA into the cytoplasm of infected cells (Figure 2). The viral genome is then translated from two ORFs to generate the nonstructural (P1234) and structural polyproteins [55]. Early in infection P1234 is cleaved in cis between nsP3 and nsP4 to yield P123 and nsP4 [56, 57]. P123 and nsP4 form an unstable initial replication complex, which is able to synthesize negative-strand RNA [1, 58–60]. Cleavage of P123 to nsP1 and P23 can only occur in trans, and only at a sufficiently high concentration of the polyprotein. The polyprotein products nsP1, P23, and nsP4 form a replication complex within virus-induced cytopathic vacuoles (CPV I) that are active in negative-strand synthesis, as well as genomic RNA synthesis, but not in subgenomic RNA synthesis [60–64]. After complete cleavage to nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4, negative-strand synthesis is inactivated and the now stable replication complex switches to synthesis of positive-strand genomic and subgenomic RNA [58, 59]. In most alphaviruses, a leaky termination codon is present following nsP3 (indicated in Figure 2), with read-through estimated to occur with only 10–20% efficiency [65]. This leads to an excess of P123 nonstructural polyprotein compared to P1234, and a depletion of nsP4 relative to the other nsPs. Further diminishing intracellular nsP4 is a destabilizing tyrosine residue at the N-terminal which signals rapid degradation by the N-end rule pathway [66]. It is worth noting that expression of a small fraction of nsP4 in cells is relatively stable, presumably in the form of replication complexes, suggesting nsP4 is only degraded when in excess [66]. Removal of the destabilizing Tyr residue leads to poor RNA replication [67].

Figure 2.

Alphavirus life-cycle. Alphavirus entry into cells is initiated by receptor-binding, followed by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Fusion to endosomal membranes transports nucleocapsid (NC) into the cytoplasm, where RNA is released after disassembly. Genomic RNA is used for both translation of proteins from genomic and subgenomic (26S) RNA, and transcription of nascent (+)RNA via a (−)RNA template. The structural proteins translated from 26S RNA encapsidate nascent genomic RNA before budding from cells, and eventual release.

Cleavage of the structural polyprotein occurs cotranslationally, beginning with the autoproteolytic cleavage of the capsid protein from the remainder of the polyprotein [18, 68, 69]. C protein is then available to associate with newly synthesized RNA, recognizing specific packaging signals in the 5′ half of the genome, such that only full-length genomic RNA is packaged into nucleocapsid-like particles [32, 33]. The E3 protein acts as a signal sequence for insertion of the remaining polyprotein into the endoplasmic reticulum, where it is processed by host signal peptidase [18, 70]. Similarly, the 6K protein acts as a signal sequence for the downstream processing of the E1 protein [51].

Upon synthesis, the E2 glycoprotein precursor, PE2 (p62 in SFV), and E1 glycoproteins interact with each other (preferentially in cis) to form heterodimers [71–73]. These heterodimer complexes are then transported from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell surface via the Golgi complex [74–76]. At a late stage of transport, the PE2 precursor is cleaved in its lumenal domain by host furin-like protease to generate mature E2 and E3 proteins [74, 76, 77]. This cleavage induces a conformational change that weakens the E1-E2 interaction in the spike heterodimer [11], priming the fusion peptide for activation upon exposure to low pH [78]. Interactions between the C protein and the cytoplasmic domain of the E2 protein drive the budding process, with E1-E2 heterodimers forming an envelope around nucleocapsid-like particles [12, 79, 80]. Upon release from cells, virions acquire a membrane bilayer derived from the host cell plasma membrane [6–9].

4. Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis

Viruses enter cells at the plasma membrane, either by fusion with membrane components at the cell surface, or by receptor attachment and internalization, followed by fusion with intracellular membranes of endocytic vesicles. Receptor-mediated endocytosis is the predominant mode of entry, most often mediated by the formation of clathrin-coated pits, and the subsequent transport to early endosomes, where the low-pH environment triggers fusion [81]. Alternatively, some viruses utilise clathrin-independent pathways to gain entry into cells. The caveolar/raft pathway transports internalised virus to neutral-pH caveosomes, before redistribution to the ER. There are also a number of clathrin-independent, caveolin-independent pathways that viruses use for cellular entry that rely on small GTPases, although these are not well understood [81].

The entry of alphaviruses into cells is facilitated by interaction of the spike E2 component with protein receptors on the surface of target cells (Figure 2) [40, 82]. A 63 KDa protein on the surface of avian cells was the first alphavirus receptor observed, although its identity was not determined [83]. Antibodies generated against BHK membrane proteins were screened to identify the 67 KDa laminin receptor as a high-affinity attachment receptor for SINV infection in mammalian cells [84]. Subsequent binding experiments of SINV to dendritic cells was shown to be SIGN dependent, with DC-SIGN and L-SIGN acting as receptor molecules [85]. Heparan sulfate, a cell surface glycosaminoglycan, may also act as an attachment receptor for alphaviruses [86–88]. However, the affinity of alphavirus binding to heparan sulfate seems to be acquired after serial passaging in cell culture, with field isolates displaying much lower affinity for heparan sulfate than laboratory-adapted strains [86–88].

Upon attachment to cellular receptors, alphaviruses are rapidly internalized and delivered to endosomes (Figure 2) [89–91]. The formation of clathrin-coated vesicles requires dynamin, a ~100 KDa protein that facilitates the budding of clathrin-coated pits, leading to the formation of coated vesicles, in a GTP-dependent manner [92]. When dominant-negative dynamin mutants specifically blocking the formation of clathrin-coated pits and vesicles were expressed [93, 94], entry of the alphaviruses CHIKV, SFV, and SINV were prevented [89, 95]. Similarly, a dominant-negative mutant of Eps15, another mediator of clathrin-dependent endocytosis, prevents entry of VEEV into cells [96]. Investigations performed using dominant-negative mutant forms of Rab5 and Rab7, genes important in endocytic trafficking to the early and late endosomes, respectively [97, 98], indicate that both SFV and VEEV are transported to early endosomes whereas only VEEV is transported to late endosomes, before fusion with target membranes [96, 99].

While the entry of alphaviruses is widely accepted to be dependent on clathrin-mediated endocytosis and fusion with endosomal membranes, the ability of alphaviruses to enter host cells via alternative mechanisms has also been reported. Supporting this hypothesis is an early study on SINV entry that showed the translation of viral RNA in the cytosol of cells, even when infected cells were treated with the weak bases chloroquine and ammonium chloride, suggesting infection involving acidic endosomes can be circumvented [100, 101]. More recently, the infection of various cell lines by SINV was shown to proceed in the absence of low-pH-induced endocytosis, indicative of entry via a clathrin-independent pathway [102–104]. Similarly, SFV infection of BHK and CHO cells following either normal virus fusion in endosomes, or experimentally induced fusion at the cell surface, highlighted the ability of alphaviruses to infect cells by an alternative pathway. Although CHO cells could only be infected following the endocytic pathway, BHK cells were able to be infected efficiently following fusion in either endosomes or at the plasma membrane, as evidenced by viral RNA and protein synthesis [105]. In agreement with this was the finding that SFV could be found inside noncoated pits and vesicles [106]. When siRNA was used to knock-down clathrin heavy chain, CHIKV infection of both HEK293 and HeLa cells was unaffected [107]. Interestingly, experiments using anti-clathrin antibodies showed only a ~60% block in SFV infection [90]. This partial block in infection could mean that either the antibodies do not inhibit the clathrin pathway completely, or that SFV can also enter through an alternative pathway that does not require clathrin. Such a scenario may also be true for CHIKV, where dominant-negative mutants of Eps15, Rab5, and drug inhibitors of endocytosis, showed only partial block in infection, supporting the hypothesis that several pathways are hijacked by CHIKV to penetrate into target cells [107].

5. Fusion

Early studies revealed the E1 protein of alphaviruses to be the fusion protein [38, 53, 54, 108–110]. Furthermore, removal of the E2 protein by protease digestion suggested that the E1 protein alone is sufficient for membrane fusion to occur [111]. However, fusogenic activity of the E1 protein is suppressed by interaction with the E2 protein [11]. Within endosomal vesicles, the E1-E2 heterodimer undergoes irreversible conformational changes upon exposure to pH of ~6 or below [91, 109, 112–115]. This low-pH environment liberates the E1 subunit from association with the E2 subunit, allowing the rearrangement to a homotrimeric complex active for fusion [108, 109, 116, 117]. E1 homotrimers associate with the target membrane via membrane insertion of the hydrophobic fusion peptide to form pores in both cellular and viral membranes for release of nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm (Figure 2) [111, 118, 119]. The fusion process occurs very rapidly, before alphaviruses are at risk of lysosomal degradation [115]. Treatment of cells with lysosomotropic weak bases chloroquine, concanamycin, ammonium chloride, bafilomycin, or monensin neutralizes the pH in endosomes, preventing fusion with membranes [91, 96, 99, 107, 120, 121].

In addition to a dependence on low pH, the fusion of alphaviruses to membranes requires the presence of cholesterol [107, 108, 114, 115, 122–125]. Small amounts of sphingolipid are also required in target membranes for an as yet unidentified role during the fusion reaction itself [114, 123, 126]. Cholesterol appears to be necessary for the hydrophobic interaction of the alphavirus E1 ectodomain with the target membrane leading up to fusion [113, 127]. However, this cholesterol-dependence differs amongst the alphaviruses; while the entry of CHIKV, SFV, and SINV is inhibited by the depletion of cholesterol, VEEV is still able to enter cells under similar conditions [96, 107]. It was proposed that variations between the envelope proteins of VEEV compared to other alphaviruses may account for these observed differences [125]. As predicted, cholesterol dependence of SFV and SINV were attributed to a specific residue within the E1 protein at position 226 [125]. Viruses containing an E1-P226S mutation are more efficient at fusion in the absence of cholesterol compared to wild-type, with the E1 protein converting to the active fusion homotrimer more readily [128, 129]. Sequence analysis of the VEEV E1 protein shows that this mutation is already present [96]. It has been shown that the membranes of early endosomes are enriched in cholesterol whereas late endosomes are depleted of membrane cholesterol [130, 131]. This has been used to explain the differences in cholesterol requirement, since SFV appears to undergo fusion in early endosomes while VEEV traffics to late endosomes, for fusion [96].

6. Nucleocapsid Disassembly

Due to steric hindrance, only a small fraction of the E1 fusion protein molecules present on the surface of an individual virus particle would be able to participate in fusion reactions within the endosomal membrane [132]. It has been proposed that the remaining fusion proteins that have not reacted with the target membrane may fold back and react with the viral membrane in which they are anchored, leading to the formation of ion-permeable pores [132]. Together, these processes allow the delivery of nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm (Figure 2), and a flow of ions through the target membrane.

The formation of ion-permeable pores by viral proteins during entry has been found with other viruses such as influenza virus, with the M2 protein implicated in the flow of protons from the endosome at low pH [133]. A similar function for the alphavirus E1 protein has been proposed [111, 119]. Indeed, the accumulation of viral structural proteins in the cell membrane during virus multiplication alters the permeability of the membrane at low pH late in infection [118, 134]. When membrane permeability of cells incubated with SINV and SFV at low pH was assessed, voltage measurements confirmed the formation of ion-permeable pores [135]. The resulting flow of protons from the endosome into the cytoplasm through this pore would lead to a region of low pH, consistent with the discovery that a low-pH environment strongly stimulates disassembly of alphavirus nucleocapsid [136].

Fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal membrane releases nucleocapsid into the cell cytoplasm (Figure 2). Uncoating of alphavirus nucleocapsids occurs almost immediately (~1 minute) after their penetration into the cytoplasm [137]. 60S ribosomal RNA interacts with the C protein, facilitating uncoating of the nucleocapsid and release of viral RNA for initiation of protein synthesis (Figure 2) [55, 137–139].

7. Conclusion

The study of alphaviruses has provided a number of insights relating to virus entry. In fact, reports on SFV were the first to demonstrate entry of viruses via receptor-mediated endocytosis, and the use of clathrin-coated vesicles [91]. The entry pathway of alphaviruses has been further elucidated, providing a greater understanding of events such as virus trafficking, fusion, and the release of genomic material into cells. However, there remain a number of questions that are yet to be resolved. One area for investigation is the identification of receptors used in alphavirus attachment to cells. So far, receptors have only been identified for SFV and SINV entry into cells. Isolating receptors could lead to the development of novel antivirals targeting alphavirus entry. Another topic for exploration is the use of alternative pathways for alphavirus entry into cells. There is growing evidence that alphaviruses are able to infect cells independent of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, either by employing a different entry pathway altogether, or being able to enter cells using several pathways. In the case of CHIKV, entry has also been shown to occur in the absence of cav-1 (required for caveolar vesicle formation) [140]. It may be possible that alphaviruses such as CHIKV are able to utilize a dynamin-dependent pathway reliant on the small GTPase RhoA [141]. This pathway does not involve clathrin, caveolae, or Eps15, yet is strongly inhibited by knock-out of dynamin, RhoA, or the depletion of cholesterol or sphingolipids, concurring with previous work. It is hoped that the continued study of alphaviruses will shed new light on the processes involved in entry.

Acknowledgment

NUS Start-up Grant (R182-000-165-133, R182-000-165-733) and Biomedical Research Council (BMRC) Research Grant (R182-000-158-305) are acknowledged. Due to space limitations, recognition and apologies are given in advance to the many colleagues whose original contributions have not been possible to cite in this curent review.

References

- 1.Strauss JH, Strauss EG. The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiological Reviews. 1994;58(3):491–562. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.491-562.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryman KD, Klimstra WB. Host responses to alphavirus infection. Immunological Reviews. 2008;225(1):27–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon F, Tolou H, Jeandel P. The unexpected Chikungunya outbreak. Revue de Medecine Interne. 2006;27(6):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2006.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancini EJ, Clarke M, Gowen B, Rutten T, Fuller SD. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals the functional organization of an enveloped virus, Semliki Forest virus. Molecular Cell. 2000;5(2):255–266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan C, Howe C, Rose HM. Structure and development of viruses as observed in the electron microscope. V. Western equine encephalomyelitis virus. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1961;113:219–234. doi: 10.1084/jem.113.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller SD. The T=4 envelope of sindbis virus is organized by interactions with a complementary T=3 capsid. Cell. 1987;48(6):923–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acheson NH, Tamm I. Replication of semliki forest virus: an electron microscopic study. Virology. 1967;32(1):128–143. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laine RA, Söderlund H, Renkonen O. Chemical composition of Semliki Forest virus. Intervirology. 1973;1(2):110–118. doi: 10.1159/000148837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel RH, Provencher S, von Bonsdorff CH. Envelope structure of Semliki Forest virus reconstructed from cryo-electron micrographs. Nature. 1986;320(6062):533–535. doi: 10.1038/320533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice CM, Strauss J. Association of Sindbis virion glycoproteins and their precursors. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1982;154(2):325–348. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahlberg J, Boere WAM, Garoff H. The heterodimeric association between the membrane proteins of Semliki Forest virus changes its sensitivity to low pH during virus maturation. Journal of Virology. 1989;63(12):4991–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.4991-4997.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen KE, Kuhn RJ. Alphavirus budding is dependent on the interaction between the nucleocapsid and hydrophobic amino acids on the cytoplasmic domain of the E2 envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 1997;230(2):187–196. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Lindqvist B, Garoff H, von Bonsdorff CH, Liljeström P. A tyrosine-based motif in the cytoplasmic domain of the alphavirus envelope protein is essential for budding. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13(18):4204–4211. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmons DT, Strauss J. Replication of Sindbis virus. I. Relative size and genetic content of 26 s and 49 s RNA. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1972;71(3):599–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss EG, Rice CM, Strauss J. Complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of Sindbis virus. Virology. 1984;133(1):92–110. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancedda R, Shatkin AJ. Ribosome-protected fragments from sindbis 42-S and 26-S RNAs. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1979;94(1):41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb12869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy WR, Strauss J. Processing the nonstructural polyproteins of Sindbis virus: nonstructural proteinase is in the C-terminal half of nsP2 and functions both in cis and in trans. Journal of Virology. 1989;63(11):4653–4664. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4653-4664.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melançon P, Garoff H. Processing of the Semliki Forest virus structural polyprotein: role of the capsid protease. Journal of Virology. 1987;61(5):1301–1309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1301-1309.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahola T, Kääriäinen L. Reaction in alphavirus mRNA capping: formation of a covalent complex of nonstructural protein nsP1 with 7-methyl-GMP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(2):507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mi S, Stollar V. Expression of Sindbis virus nsP1 and methyltransferase activity in Escherichia coli. Virology. 1991;184(1):423–427. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90862-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peränen J, Laakkonen P, Hyvönen M, Kääriäinen L. The alphavirus replicase protein nsP1 is membrane-associated and has affinity to endocytic organelles. Virology. 1995;208(2):610–620. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez de Cedrón M, Ehsani N, Mikkola ML, Kääriäinen L, García JA. RNA helicase activity of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein NSP2. The FEBS Letters. 1999;448(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikkonen M, Peränen J, Kääriäinen L. ATPase and GTPase activities associated with Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein nsP2. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(9):5804–5810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5804-5810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Auvinen P, Kääriäinen L. Identification of a novel function of the Alphavirus capping apparatus. RNA 5’-triphosphatase activity of Nsp2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(23):17281–17287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910340199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hahn YS, Strauss EG, Strauss J. Mapping of RNA- temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus: assignment of complementation groups A, B, and G to nonstructural proteins. Journal of Virology. 1989;63(7):3142–3150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3142-3150.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malet H, Gould EA, Jamal S, et al. The crystal structures of Chikungunya and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus nsP3 macro domains define a conserved adenosine binding pocket. Journal of Virology. 2009;83(13):6534–6545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00189-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park E, Griffin DE. The nsP3 macro domain is important for Sindbis virus replication in neurons and neurovirulence in mice. Virology. 2009;388(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuittila MT, Hinkkanen A. Amino acid mutations in the replicase protein nsP3 of Semliki Forest virus cumulatively affect neurovirulence. Journal of General Virology. 2003;84(6):1525–1533. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18936-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hahn YS, Grakoui A, Rice CM, Strauss EG, Strauss J. Mapping of RNA- temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus: complementation group F mutants have lesions in nsP4. Journal of Virology. 1989;63(3):1194–1202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1194-1202.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shirako Y, Strauss EG, Strauss J. Suppressor mutations that allow Sindbis virus RNA polymerase to function with nonaromatic amino acids at the N-terminus: evidence for interaction between nsP1 and nsP4 in minus-strand RNA synthesis. Virology. 2000;276(1):148–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomar S, Hardy RW, Smith JL, Kuhn RJ. Catalytic core of alphavirus nonstructural protein nsP4 possesses terminal adenylyltransferase activity. Journal of Virology. 2006;80(20):9962–9969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01067-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Owen KE, Kuhn RJ. Identification of a region in the Sindbis virus nucleocapsid protein that is involved in specificity of RNA encapsidation. Journal of Virology. 1996;70(5):2757–2763. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2757-2763.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss BG, Nitschko H, Ghattas IR, Schlesinger S, Wright RN. Evidence for specificity in the encapsidation of Sindbis virus RNAs. Journal of Virology. 1989;63(12):5310–5318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5310-5318.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perera R, Navaratnarajah CK, Kuhn RJ. A heterologous coiled coil can substitute for helix I of the Sindbis virus capsid protein. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(15):8345–8353. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8345-8353.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HK, Tong L, Minor W, et al. Structure of Sindbis virus core protein reveals a chymotrypsin-like serine proteinase and the organization of the virion. Nature. 1991;353(6348):37–43. doi: 10.1038/354037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garoff H, Simons K, Renkonen O. Isolation and characterization of the membrane proteins of Semliki Forest virus. Virology. 1974;61(2):493–504. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simizu B, Yamamoto K, Hashimoto K, Ogata T. Structural proteins of Chikungunya virus. Journal of Virology. 1984;51(1):254–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.1.254-258.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garoff H, Frischauf AM, Simons K. Nucleotide sequence of cDNA coding for Semliki Forest virus membrane glycoproteins. Nature. 1980;288(5788):236–241. doi: 10.1038/288236a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu N, Brown DT. Transient translocation of the cytoplasmic (endo) domain of a type I membrane glycoprotein into cellular membranes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120(4):877–883. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith T, Cheng RH, Olson N, et al. Putative receptor binding sites on alphaviruses as visualized by cryoelectron microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(23):10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis NL, Fuller FJ, Dougherty WG. A single nucleotide change in the E2 glycoprotein gene of Sindbis virus affects penetration rate in cell culture and virulence in neonatal mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(18):6771–6775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tucker PC, Lee SH, Bui N, Griffin DE, Martinie D. Amino acid changes in the sindbis virus E2 glycoprotein that increase neurovirulence improve entry into neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(8):6106–6112. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6106-6112.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ubol S, Tucker PC, Griffin DE, Hardwick JM. Neurovirulent strains of Alphavirus induce apoptosis in bcl-2-expressing cells: role of a single amino acid change in the E2 glycoprotein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(11):5202–5206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skoging-Nyberg U, Liljeström P. A conserved leucine in the cytoplasmic domain of the Semliki Forest virus spike protein is important for budding. Archives of Virology. 2000;145(6):1225–1230. doi: 10.1007/s007050070121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ivanova L, Schlesinger M. Site-directed mutations in the Sindbis virus E2 glycoprotein identify palmitoylation sites and affect virus budding. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(5):2546–2551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2546-2551.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaedigk-Nitschko K, Schlesinger MJ. The Sindbis virus 6K protein can be detected in virions and is acylated with fatty acids. Virology. 1990;175(1):274–281. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90209-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivanova L, Le LD, Schlesinger MJ. Characterization of revertants of a Sindbis virus 6K gene mutant that affects proteolytic processing and virus assembly. Virus Research. 1995;39(2-3):165–179. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lusa S, Garoff H, Liljeström P. Fate of the 6K membrane protein of Semliki Forest virus during virus assembly. Virology. 1991;185(2):843–846. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90556-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanz MA, Carrasco L. Sindbis virus variant with a deletion in the 6K gene shows defects in glycoprotein processing and trafficking: lack of complementation by a wild-type 6K gene in trans. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(16):7778–7784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7778-7784.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melton J, Ewart G, Weir RC, Lee EK, Board PG, Gage PW. Alphavirus 6K proteins form ion channels. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(49):46923–46931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanz MA, Madan V, Carrasco L, Nieva JL. Interfacial domains in sindbis virus 6K protein: detection and functional characterization. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(3):2051–2057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanz MA, Perez LG, Carrasco L. Semliki forest virus 6K protein modifies membrane permeability after inducible expression in Escherichia coli cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(16):12106–12110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boggs WM, Hahn CS, Strauss EG, Strauss J, Griffin DE. Low pH-dependent Sindbis virus-induced fusion of BHK cells: differences between strains correlate with amino acid changes in the E1 glycoprotein. Virology. 1989;169(2):485–488. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Omar A, Koblet H. Semliki Forest virus particles containing only the E1 envelope glycoprotein are infectious and can induce cell-cell fusion. Virology. 1988;166(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glanville NT, Ranki M, Morser J. Initiation of translocation directed by 42S and 26S RNAs from Semliki Forest virus in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73(9):3059–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Groot RJ, Hardy WR, Shrako Y, Strauss J. Cleavage-site preferences of Sindbis virus polyproteins contains the non-structural proteinase. Evidence for temporal regulation of polyprotein processing in vivo. The EMBO Journal. 1990;9(8):2631–2638. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takkinen K, Peränen J, Kääriäinen L. Proteolytic processing of Semliki Forest virus-specific non-structural polyprotein. Journal of General Virology. 1991;72(7):1627–1633. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lemm JA, Rümenapf T, Strauss EG, Rice CM, Strauss J. Polypeptide requirements for assembly of functional Sindbis virus replication complexes: a model for the temporal regulation of minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13(12):2925–2934. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shirako Y, Strauss J. Regulation of Sindbis virus RNA replication: uncleaved P123 and nsP4 function in minus-strand RNA synthesis, whereas cleaved products from P123 are required for efficient plus-strand RNA synthesis. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(3):1874–1885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1874-1885.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dé I, Sawicki SG, Sawicki DL. Sindbis virus RNA-negative mutants that fail to convert from minus-strand to plus-strand synthesis: role of the nsP2 protein. Journal of Virology. 1996;70(5):2706–2719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2706-2719.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Froshauer SA, Kartenbeck J, Helenius A. Alphavirus RNA replicase is located on the cytoplasmic surface of endosomes and lysosomes. Journal of Cell Biology. 1988;107(6):2075–2086. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kujala P, Ikäheimonen A, Ehsani N, Vihinen H, Kääriäinen L, Auvinen P. Biogenesis of the Semliki Forest virus RNA replication complex. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(8):3873–3884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3873-3884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salonen AH, Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Kääriäinen L, Magden J, Jokitalo E. Properly folded nonstructural polyprotein directs the semliki forest virus replication complex to the endosomal compartment. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(3):1691–1702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1691-1702.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.LaStarza MW, Lemm JA, Rice CM. Genetic analysis of the nsP3 region of Sindbis virus: evidence for roles in minus-strand and subgenomic RNA synthesis. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(9):5781–5791. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5781-5791.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li G, Rice CM. The signal for translational readthrough of a UGA codon in sindbis virus RNA involves a single cytidine residue immediately downstream of the termination codon. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(8):5062–5067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.5062-5067.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Groot RJ, Rümenapf T, Kuhn RJ, Strauss EG, Strauss J. Sindbis virus RNA polymerase is degraded by the N-end rule pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(20):8967–8971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shirako Y, Strauss J. Requirement for an aromatic amino acid or histidine at the N terminus of sindbis virus RNA polymerase. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(3):2310–2315. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2310-2315.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aliperti G, Schlesinger M. Evidence for an autoprotease activity of Sindbis virus capsid protein. Virology. 1978;90(2):366–369. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garoff H, Simons K, Dobberstein B. Assembly of the semliki forest virus membrane glycoproteins in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum in vitro. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1978;124(5):587–600. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lobigs M, Hongxing Z, Garoff H. Function of Semliki Forest virus E3 peptide in virus assembly: replacement of E3 with an artificial signal peptide abolishes spike heterodimerization and surface expression of E1. Journal of Virology. 1990;64(9):4346–4355. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4346-4355.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duffus WA, Levy-Mintz P, Klimjack MR, Kielian M. Mutations in the putative fusion peptide of Semliki Forest virus affect spike protein oligomerization and virus assembly. Journal of Virology. 1995;69(4):2471–2479. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2471-2479.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Andersson HH, Barth BU, Ekström M, Garoff H. Oligomerization-dependent folding of the membrane fusion protein of semliki forest virus. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(12):9654–9663. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9654-9663.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barth BU, Wahlberg JM, Garoff H. The oligomerization reaction of the Semliki forest virus membrane protein subunits. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;128(3):283–291. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Curtis I, Simons K. Dissection of Semliki Forest virus glycoprotein delivery from the trans-Golgi network to the cell surface in permeabilized BHK cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(21):8052–8056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Green J, Griffiths G, Louvard D. Passage of viral membrane proteins through the Golgi complex. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1981;152(4):663–698. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sariola M, Saraste J, Kuismanen E. Communication of post-Golgi elements with early endocytic pathway: regulation of endoproteolytic cleavage of Semliki Forest virus p62 precursor. Journal of Cell Science. 1995;108, part 6:2465–2475. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ziemiecki A, Garoff H, Simons K. Formation of the Semliki Forest virus membrane glycoprotein complexes in the infected cell. Journal of General Virology. 1980;50(1):111–123. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-1-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lobigs M, Garoff H. Fusion function of the Semliki Forest virus spike is activated by proteolytic cleavage of the envelope glycoprotein precursor p62. Journal of Virology. 1990;64(3):1233–1240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1233-1240.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Metsikkö K, Garoff H. Oligomers of the cytoplasmic domain of the p62/E2 membrane protein of Semliki Forest virus bind to the nucleocapsid in vitro. Journal of Virology. 1990;64(10):4678–4683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4678-4683.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vaux D, Helenius A, Mellman I. Spike-nucleocapsid interaction in Semliki Forest virus reconstructed using network antibodies. Nature. 1988;336(6194):36–42. doi: 10.1038/336036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayor S, Pagano RE. Pathways of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(8):603–612. doi: 10.1038/nrm2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Smith AL, Tignor GH. Host cell receptors for two strains of Sindbis virus. Archives of Virology. 1980;66(1):11–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01315041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang KS, Schmaljohn AL, Kuhn RJ, Strauss J. Antiidiotypic antibodies as probes for the Sindbis virus receptor. Virology. 1991;181(2):694–702. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90903-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang KS, Kuhn RJ, Strauss EG, Strauss J, Ou S. High-affinity laminin receptor is a receptor for Sindbis virus in mammalian cells. Journal of Virology. 1992;66(8):4992–5001. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4992-5001.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klimstra WB, Nangle EM, Smith MS, Yurochko AD, Ryman KD. DC-SIGN and L-SIGN can act as attachment receptors for alphaviruses and distinguish between mosquito cell- and mammalian cell-derived viruses. Journal of Virology. 2003;77(22):12022–12032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12022-12032.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bernard K, Klimstra WB, Johnston RE. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus confer heparan sulfate interaction, low morbidity, and rapid clearance from blood of mice. Virology. 2000;276(1):93–103. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Heil M, Albee A, Strauss J, Kuhn RJ. An amino acid substitution in the coding region of the E2 glycoprotein adapts ross river virus to utilize heparan sulfate as an attachment moiety. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(14):6303–6309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6303-6309.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klimstra WB, Ryman KD, Johnston RE. Adaptation of Sindbis virus to BHK cells selects for use of heparan sulfate as an attachment receptor. Journal of Virology. 1998;72(9):7357–7366. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7357-7366.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.DeTulleo L, Kirchhausen T. The clathrin endocytic pathway in viral infection. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(16):4585–4593. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Doxsey S, Brodsky FM, Blank G, Helenius A. Inhibition of endocytosis by anti-clathrin antibodies. Cell. 1987;50(3):453–463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Helenius A, Kartenbeck J, Simons K, Fries E. On the entry of Semliki Forest virus into BHK-21 cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1980;84(2):404–420. doi: 10.1083/jcb.84.2.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.van der Bliek AM, Redelmeier T, Damke H, Schmid SL, Meyerowitz EM, Tisdale EJ. Mutations in human dynamin block an intermediate stage in coated vesicle formation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;122(3):553–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.3.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baba T, Damke H, Hinshaw JE, Warnock D, Ikeda K, Schmid SL. Role of dynamin in clathrin-coated vesicle formation. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 1995;60:235–242. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Damke H, Baba T, Warnock D, Schmid SL. Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic coated vesicle formation. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;127(4):915–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sourisseau M, Schilte C, Casartelli N, et al. Characterization of reemerging chikungunya virus. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3(6, article e89) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kolokoltsov AA, Fleming EH, Davey RA. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus entry mechanism requires late endosome formation and resists cell membrane cholesterol depletion. Virology. 2006;347(2):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH, et al. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell. 1992;70(5):715–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bucci C, Thomsen PD, Nicoziani P, McCarthy J, Van Deurs B. Rab7: a key to lysosome biogenesis. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11(2):467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Colpitts TM, Moore A, Kolokoltsov AA, Davey RA. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection of mosquito cells requires acidification as well as mosquito homologs of the endocytic proteins Rab5 and Rab7. Virology. 2007;369(1):78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cassell S, Edwards J, Brown DT. Effects of lysosomotropic weak bases on infection of BHK-21 cells by Sindbis virus. Journal of Virology. 1984;52(3):857–864. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.857-864.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coombs K, Mann E, Edwards J, Brown DT. Effects of chloroquine and cytochalasin B on the infection of cells by Sindbis virus and vesicular stomatitis virus. Journal of Virology. 1981;37(3):1060–1065. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.3.1060-1065.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hernandez R, Luo T, Brown DT. Exposure to low pH is not required for penetration of mosquito cells by sindbis virus. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(4):2010–2013. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.2010-2013.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Paredes A, Ferreira DF, Horton M, et al. Conformational changes in Sindbis virions resulting from exposure to low pH and interactions with cells suggest that cell penetration may occur at the cell surface in the absence of membrane fusion. Virology. 2004;324(2):373–386. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang G, Hernandez R, Weninger KR, Brown DT. Infection of cells by Sindbis virus at low temperature. Virology. 2007;362(2):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marsh M, Bron R. SFV infection in CHO cells: cell-type specific restrictions to productive virus entry at the cell surface. Journal of Cell Science. 1997;110, part 1:95–103. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hase T, Summers PL, Cohen WH. A comparative study of entry modes into C 6/36 cells by Semliki Forest Japanese encephalitis viruses. Archives of Virology. 1989;108(1-2):101–114. doi: 10.1007/BF01313747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bernard EA, Solignat M, Gay B, et al. Endocytosis of chikungunya virus into mammalian cells: role of clathrin and early endosomal compartments. PLoS One. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011479. Article ID e11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kielian M, Helenius A. pH-Iinduced alterations in the fusogenic spike protein of Semliki Forest virus. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101(6):2284–2291. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Justman J, Klimjack MR, Kielian M. Role of spike protein conformational changes in fusion of Semliki Forest virus. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(12):7597–7607. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7597-7607.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sanz MA, Rejas MT, Carrasco L. Individual expression of Sindbis virus glycoproteins. E1 alone promotes cell fusion. Virology. 2003;305(2):463–472. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Spyr C, Käsermann F, Kempf C. Identification of the pore forming element of Semliki Forest virus spikes. The FEBS Letters. 1995;375(1-2):134–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01197-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bron R, Wahlberg J, Garoff H, Wilschut J. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus in a model system: correlation between fusion kinetics and structural changes in the envelope glycoprotein. The EMBO Journal. 1993;12(2):693–701. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Klimjack MR, Jeffrey S, Kielian M. Membrane and protein interactions of a soluble form of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein. Journal of Virology. 1994;68(11):6940–6946. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6940-6946.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Smit JM, Bittman R, Wilschut J. Low-pH-dependent fusion of Sindbis virus with receptor-free cholesterol- and sphingolipid-containing liposomes. Journal of Virology. 1999;73(10):8476–8484. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8476-8484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.White J, Helenius A. pH-Dependent fusion between the Semliki Forest virus membrane and liposomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77(6):3273–3277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wahlberg J, Bron R, Wilschut J, Garoff H. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus involves homotrimers of the fusion protein. Journal of Virology. 1992;66(12):7309–7318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7309-7318.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wahlberg J, Garoff H. Membrane fusion process of Semliki Forest virus I: low pH-induced rearrangement in spike protein quaternary structure precedes virus penetration into cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;116(2):339–348. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lanzrein M, Weingart R, Kempf C. PH-dependent pore formation in Semliki forest virus-infected Aedes albopictus cells. Virology. 1993;193(1):296–302. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schlegel A, Omar A, Jentsch P, Kempf C, Morell A. Semliki Forest virus envelope proteins function as proton channels. Bioscience Reports. 1991;11(5):243–255. doi: 10.1007/BF01127500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Helenius A, Marsh M, White JM. Inhibition of Semliki Forest virus penetration by lysosomotropic weak bases. Journal of General Virology. 1982;58(1):47–61. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-58-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Marsh M, Wellsteed J, Kern H. Monensin inhibits Semliki Forest virus penetration into culture cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79(17):5297–5301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Phalen T, Kielian M. Cholesterol is required for infection by Semliki Forest virus. Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;112(4):615–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wilschut J, Corver J, Nieva JL, et al. Fusion of Semliki Forest virus with cholesterol-containing liposomes at low pH: a specific requirement for sphingolipids. Molecular Membrane Biology. 1995;12(1):143–149. doi: 10.3109/09687689509038510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ahn A, Gibbons DL, Kielian M. The fusion peptide of Semliki Forest virus associates with sterol-rich membrane domains. Journal of Virology. 2002;76(7):3267–3275. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3267-3275.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lu YE, Cassese T, Kielian M. The cholesterol requirement for sindbis virus entry and exit and characterization of a spike protein region involved in cholesterol dependence. Journal of Virology. 1999;73(5):4272–4278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.4272-4278.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Nieva JL, Bron R, Corver J, Wilschut J. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus requires sphingolipids in the target membrane. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13(12):2797–2804. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kielian M, Helenius A. Role of cholesterol in fusion of Semliki Forest virus with membranes. Journal of Virology. 1984;52(1):281–283. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.281-283.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chatterjee PK, Vashishtha M, Kielian M. Biochemical consequences of a mutation that controls the cholesterol dependence of Semliki Forest virus fusion. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(4):1623–1631. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1623-1631.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vashishtha M, Phalen T, Marquardt MT, Ryu JS, Kielian M, Ng AC. A single point mutation controls the cholesterol dependence of Semliki Forest virus entry and exit. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;140(1):91–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Evans WH, Hardison WG. Phospholipid, cholesterol, polypeptide and glycoprotein composition of hepatic endosome subfractions. Biochemical Journal. 1985;232(1):33–36. doi: 10.1042/bj2320033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kobayashi T, Beuchat MH, Chevallier J, et al. Separation and characterization of late endosomal membrane domains. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(35):32157–32164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wengler G, Koschinski A, Wengler G, Repp H. During entry of alphaviruses, the E1 glycoprotein molecules probably form two separate populations that generate either a fusion pore or ion-permeable pores. Journal of General Virology. 2004;85(6):1695–1701. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Duff KC, Ashley RH. The transmembrane domain of influenza A M2 protein forms amantadine- sensitive proton channels in planar lipid bilayers. Virology. 1992;190(1):485–489. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91239-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Dick M, Barth BU, Kempf C. The E1 protein is mandatory for pore formation by Semliki Forest virus spikes. Virology. 1996;220(1):204–207. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wengler G, Koschinski A, Wengler G, Dreyer F. Entry of alphaviruses at the plasma membrane converts the viral surface proteins into an ionpermeable pore that can be detected by electrophysiological analyses of whole-cell membrane currents. Journal of General Virology. 2003;84(1):173–181. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wengler G, Wengler G. In vitro analysis of factors involved in the disassembly of Sindbis virus cores by 60S ribosomal subunits identifies a possible role of low pH. Journal of General Virology. 2002;83, part 10:2417–2426. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-10-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Singh IR, Helenius A. Role of ribosomes in Semliki Forest virus nucleocapsid uncoating. Journal of Virology. 1992;66(12):7049–7058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7049-7058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ulmanen I, Söderlund H, Kääriäinen L. Semliki forest virus capsid protein associates with the 60S ribosomal subunit in infected cells. Journal of Virology. 1976;20(1):203–210. doi: 10.1128/jvi.20.1.203-210.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wengler G, Wurkner D, Wengler G. Identification of a sequence element in the alphavirus core protein which mediates interaction of cores with ribosomes and the disassembly of cores. Virology. 1992;191(2):880–888. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90263-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Solignat M, Gay B, Higgs S, et al. Replication cycle of chikungunya: a re-emerging arbovirus. Virology. 2009;393(2):183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lamaze C, Dujeancourt A, Baba T, et al. Interleukin 2 receptors and detergent-resistant membrane domains define a clathrin-independent endocytic pathway. Molecular Cell. 2001;7(3):661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]